Abstract

Increased heart rate is a predictor of cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and all‐cause mortality. In those with high heart rates, interventions for heart rate reduction have been associated with reductions in coronary events. Asia is a diverse continent, and the prevalences of hypertension and cardiovascular disease differ among its countries. The present analysis of AsiaBP@Home study data investigated differences among resting heart rates (RHRs) in 1443 hypertensive patients from three Asian regions: East Asia (N = 595), Southeast Asia (N = 680), and South Asia (N = 168). This is the first study to investigate self‐measured RHR values in different Asian countries/regions using the same validated home BP monitoring device (Omron HEM‐7130‐AP/HEM‐7131‐E). Subjects in South Asia had higher RHR values compared with the other two regions, and the regional tendency found in RHR values was different from that found in BP values. Even after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, habitual alcohol consumption, current smoking habit, shift worker, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, history of heart failure, and beta‐blocker use, both office and home RHR values in South Asia were the highest among Asia (mean values ± SE of office: East Asia [E] 75.2 ± 1.5 bpm, Southeast Asia [Se] 76.7 ± 1.5 bpm, South Asia [S] 81.9 ± 1.4 bpm; home morning: [E] 69.0 ± 1.2 bpm, [Se] 72.9 ± 1.2 bpm, [S] 74.9 ± 1.1 bpm; home evening: [E] 74.6 ± 1.2 bpm, [Se] 78.3 ± 1.2 bpm, [S] 83.8 ± 1.1 bpm). Given what is known about the impact of RHR on heart disease, our findings suggest the possible benefit of regionally tailored clinical strategies for cardiovascular disease prevention.

Keywords: Asia, AsiaBP@Home study, resting heart rate, self‐measured home heart rate, validated blood pressure monitoring device

1. INTRODUCTION

Increased resting heart rate (RHR) is recognized as a predictor of cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and all‐cause mortality in both general populations and high‐risk patients. 1 , 2 , 3 In these studies, a single RHR measurement, performed at hospital or clinic, was used for the evaluation. However, a Japanese study in the general population demonstrated that the average of multiple home RHR measurements using a home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) device was directly associated with cardiovascular mortality. 4 In addition, Böhn and colleagues recently reported that the sympathetic modulation caused by renal denervation reduced not only blood pressure (BP) levels but also ambulatory heart rate, and that greater BP reduction was observed in patients with higher baseline heart rate. 5 An interventional randomized controlled trial with ivabradine, a specific inhibitor of the If current in the sinoatrial node, demonstrated that reduction in heart rate per se significantly reduced the risk of future coronary artery disease. 6 Taken together, these data suggest that heart rate is an important clinical indicator in the management of hypertension and cardiovascular risk.

A report from the US population survey showed the existence of significant racial differences in RHR. 7 In a recent analysis, race‐ and sex‐specific differences in the association of RHR during young adulthood with incident hypertension in later life were observed among black and white men and women. 8 We reasoned that investigating race‐ and sex‐specific differences in RHR among Asian regions, which has never been studied before, might uncover geographic trends that could inform clinical implications and strategies in those regions. Asia is a diverse continent consisting of countries with different climates, cultures, food, and incomes, not to mention population genetics. These differences, as well as differences in the awareness, treatment, and control rate of hypertension among Asian countries, 9 might be the source of disparities in heart rate that, in turn, impact on hypertension and cardiovascular risk even in the same continent, Asia.

We previously reported the evidence for substantial differences in BP control status and BP variability among Asian countries/regions in the AsiaBP@Home study. 10 The AsiaBP@Home is the first Asian simultaneous cross‐sectional study to investigate home BP control status in major hypertension specialist centers across Asia using the same validated device and the same home BP measurement protocol. In the present analysis of the AsiaBP@Home data, we focused on self‐measured home RHRs which measured for multiple days according to the same measurement protocol and investigated region‐ and sex‐specific differences in home RHRs measured by the same HBPM device in hypertensive patients in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

The AsiaBP@Home study design has been described in detail previously. 11 In brief, the study was a prospective, multicenter, non‐interventional trial designed to collect home BP data from outpatients living in eleven countries in three regions of Asia. All patients provided written informed consent before study enrollment, and the study protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each study center. The study was registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov website (NCT03096119).

2.2. Study participants

Patients aged 20 years and older with a diagnosis of hypertension who had been receiving stable doses of antihypertensive medications for ≥3 months were recruited from 15 Asian specialist hypertension centers in three Asian regions. “East Asia” included centers in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan; “Southeast Asia,” Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand; and “South Asia,” India and Pakistan. Patients were enrolled between April 2017 and March 2018.

2.3. BP and heart rate measurements

Patients were provided with the same validated automatic, oscillometric home BP monitoring device (Omron HEM‐7130‐AP or HEM‐7131‐E; Omron Healthcare) 12 and instructed to measure their BP and heart rate at home for at least 7 days during a 15‐day home BP monitoring period. To avoid reporting bias, BP and heart rate data were automatically stored in device memory, which will be entered into the study database by a physician or nurse.

Patients measured their BP and heart rate at home using the provided device twice in the morning (morning home BP) and twice at bedtime (evening home BP) at 1‐min intervals. Patients were instructed to take morning measurements within 1 h after waking, following urination, before taking any medications, before eating breakfast, and after 2 min of rest in a sitting position with no moving or talking. Bedtime measurements were to be taken immediately before going to bed and after 2 min of rest in a sitting position. For each subject, the mean values of the morning BP, morning heart rate, evening BP, and evening heart rate during the BP monitoring period (7–15 days) were used as the subject's morning BP, morning heart rate, evening BP, and evening heart rate, respectively.

Clinic BP and heart rate were measured twice at the initial visit and again (if applicable) at the second study visit.

2.4. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute) at the Super Circulation Monitoring with High Technology (SURGE) R&D Center of the Jichi Medical University COE Cardiovascular Research and Development Center (JCARD) (Tochigi, Japan). A linear regression or multivariable linear regression model was used to assess differences among the three Asian regions. In the sensitivity analysis, we performed similar analyses in the population excluding those with prevalent heart failure, beta‐blocker use, and alcohol habit, all of which generally affect heart rate.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient demographics and characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographics of the patients recruited from hypertension centers in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. There were significant differences in the patients’ ages, body mass index (BMI), habits, complications, and medical history among the regions. The types of antihypertensive medication and the prevalence of bedtime dosing of antihypertensive medication varied among regions. Patients’ demographics in each of 15 centers were previously reported and are shown in the Table S1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics and characteristics

| East Asia (N = 595) | Southeast Asia (N = 680) | South Asia (N = 168) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.8 ± 11.6 | 60.6 ± 11.6 | 57.0 ± 12.7 | <.001 |

| Male, % | 48.1 | 43.8 | 59.5 | .001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.3 ± 3.5 | 25.9 ± 4.6 | 29.0 ± 5.6 | <.001 |

| Habitual drinking, % | 12.8 | 4.7 | 26.8 | <.001 |

| Current smoking, % | 9.4 | 4.7 | 19.6 | <.001 |

| Shift worker, % | 1.2 | 2.4 | 13.1 | <.001 |

| Current disease, % | ||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 49.4 | 59.0 | 32.7 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 21.5 | 26.8 | 31.0 | .017 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4.4 | 6.0 | 8.3 | .109 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6.1 | 1.3 | 5.4 | <.001 |

| Medical history, % | ||||

| Angina pectoris | 16.0 | 4.9 | 11.3 | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 4.2 | 2.1 | 6.0 | .014 |

| Aortic dissection | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | .389 |

| Heart failure | 1.5 | 1.0 | 23.8 | <.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | .541 |

| Stroke | 7.1 | 6.9 | 2.4 | .052 |

| Antihypertensive medication, % | ||||

| ARB | 63.7 | 41.2 | 32.1 | <.001 |

| ACE | 6.9 | 14.4 | 17.3 | <.001 |

| CCB | 68.6 | 68.7 | 46.4 | <.001 |

| Alpha‐blocker | 4.4 | 3.2 | 3.6 | .555 |

| Beta‐blocker | 32.3 | 20.2 | 58.9 | <.001 |

| Diuretics | 22.9 | 12.1 | 21.4 | <.001 |

| Other | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0 | .435 |

| Number of antihypertensive medications | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | <.001 |

| Bedtime dosing of antihypertensive medications, % | 4.9 | 0.6 | 48.8 | <.001 |

| Resting heart rate and BP measurements | ||||

| Office BP measurement | ||||

| Office heart rate, bpm | 71.8 ± 11.0 | 74.9 ± 11.6 | 80.7 ± 12.7 | <.001 |

| Office SBP, mmHg | 135.9 ± 16.6 | 142.1 ± 19.4 | 135.8 ± 18.2 | <.001 |

| Office DBP, mmHg | 79.5 ± 9.8 | 84.5 ± 12.1 | 82.4 ± 8.7 | <.001 |

| Home BP measurement | ||||

| Morning measurement, days | 7.2 ± 1.2 | 9.0 ± 3.4 | 7.7 ± 2.2 | <.001 |

| Morning heart rate, bpm | 67.1 ± 8.7 | 71.9 ± 9.7 | 74.8 ± 8.3 | <.001 |

| Morning SBP, mmHg | 129.7 ± 13.3 | 131.6 ± 16.2 | 127.7 ± 11.6 | .003 |

| Morning DBP, mmHg | 80.0 ± 9.0 | 81.1 ± 10.6 | 80.5 ± 6.1 | .137 |

| Evening measurement, days | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 8.9 ± 3.5 | 7.7 ± 2.0 | <.001 |

| Evening heart rate, bpm | 69.4 ± 9.3 | 74.0 ± 9.7 | 82.2 ± 11.3 | <.001 |

| Evening SBP, mmHg | 126.2 ± 13.2 | 130.0 ± 16.6 | 136.0 ± 15.5 | <.001 |

| Evening DBP, mmHg | 76.5 ± 8.7 | 78.4 ± 10.6 | 82.1 ± 7.5 | <.001 |

Data are shown as the mean ± SD or percentage.

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blocker; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

3.2. Resting heart rate and BP measurements

The study patients measured home morning BP and RHR over an average of 8.1 ± 2.7 days and home evening BP and RHR over an average of 8.1 ± 2.7 days.

The office RHR and self‐measured, home RHR values were significantly different among the three Asian regions (all P < .001), with the highest values in South Asia. The office and home SBP values were also significantly different among the regions (all P < .01), with the highest office and morning SBP in Southeast Asia and the highest evening SBP in South Asia (Table 1). Even after excluding subjects with atrial fibrillation, the results were similar (Data not shown).

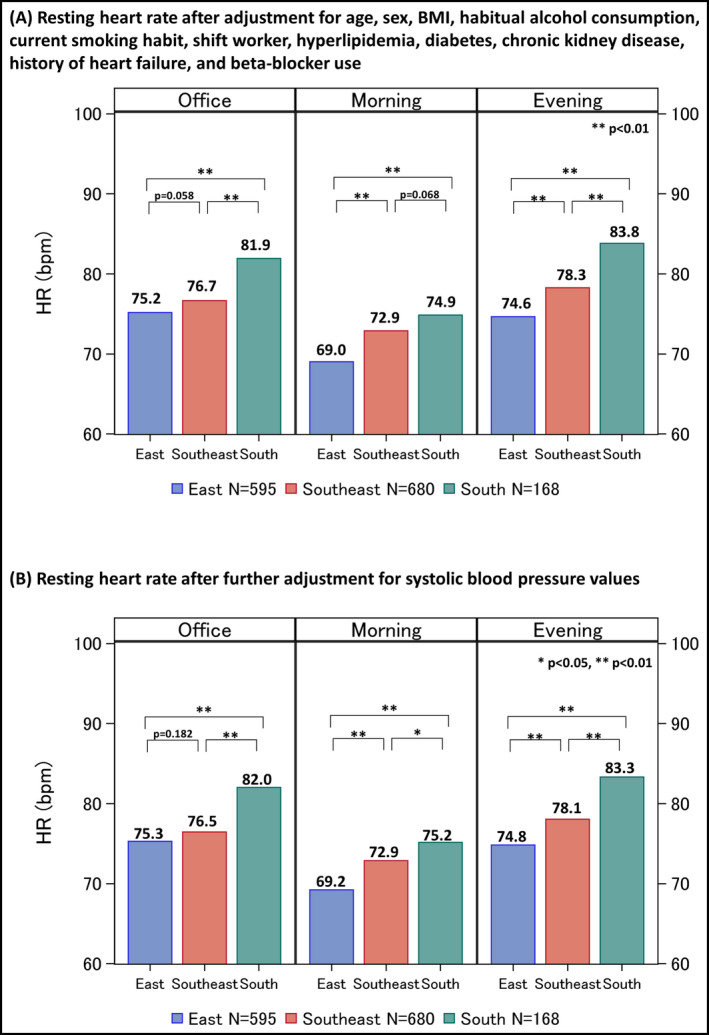

Figure 1 shows the RHR values of the three Asian regions adjusting for age, sex, BMI, habitual alcohol consumption, current smoking habit, shift worker, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, history of heart failure, and beta‐blocker use. Compared with the subjects in East Asia and Southeast Asia, subjects in South Asia had higher RHRs for both office and home measurements (mean values ± SE of office: East Asia [E] 75.2 ± 1.5 bpm, Southeast Asia [Se] 76.7 ± 1.5 bpm, South Asia [S] 81.9 ± 1.4 bpm; home morning: [E] 69.0 ± 1.2 bpm, [Se] 72.9 ± 1.2 bpm, [S] 74.9 ± 1.1 bpm; home evening: [E] 74.6 ± 1.2 bpm, [Se] 78.3 ± 1.2 bpm, [S] 83.8 ± 1.1 bpm) (Figure 1A). In addition, both office and home RHRs in South Asia were significantly higher than those in East Asia and Southeast Asia with further adjustment for systolic blood pressure values (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Multivariable adjusted resting heart rate by Asian regions (N = 1443) (A) Resting heart rate after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, habitual alcohol consumption, current smoking habit, shift worker, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, history of heart failure, and beta‐blocker use, and (B) Resting heart rate after further adjustment for office, morning, or evening systolic blood pressure values. The number shown above each bar chart is an estimated mean value. BMI, body mass index; HR, heart rate. *P < .05, **P < .01

The percentage of subjects being treated with a beta‐blocker was remarkably higher in South Asia than in East and Southeast Asia ([E] 32.3%, [Se] 20.2%, [S] 58.9%). Table 2 shows the differences in RHRs between subjects taking a beta‐blocker and those without. In East and Southeast Asia, subjects with taking a beta‐blocker had lower office and home RHR values compared with those without. However, no significant difference was found in South Asia.

TABLE 2.

Multivariable adjusted heart rate in subjects with taking a beta‐blocker versus those without

| Subjects with Beta‐blocker use (N = 428) | Subjects without Beta‐blocker use (N = 1015) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Office heart rate, bpm | |||

| East Asia | 73.5 ± 1.6 | 77.4 ± 1.5 | <.001 |

| Southeast Asia | 72.2 ± 1.7 | 79.7 ± 1.5 | <.001 |

| South Asia | 80.8 ± 1.5 | 82.7 ± 1.7 | .878 |

| Home morning heart rate, bpm | |||

| East Asia | 68.0 ± 1.3 | 70.2 ± 1.2 | .066 |

| Southeast Asia | 70.8 ± 1.3 | 74.3 ± 1.2 | <.001 |

| South Asia | 74.5 ± 1.2 | 74.9 ± 1.4 | 1.000 |

| Home evening heart rate, bpm | |||

| East Asia | 73.0 ± 1.3 | 76.4 ± 1.3 | <.001 |

| Southeast Asia | 75.4 ± 1.4 | 80.3 ± 1.2 | <.001 |

| South Asia | 83.9 ± 1.3 | 83.2 ± 1.4 | .998 |

Data are least square mean ± SE in a multivariable regression model adjusting for age, sex, BMI, habitual alcohol consumption, current smoking habit, shift worker, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, history of heart failure, beta‐blocker use, and interaction between Area and beta‐blocker use.

When we excluded subjects with a history of heart failure, the South Asian subjects had the highest office and home evening RHR measurements. Morning RHR values in the Southeast and South Asian subjects were significantly higher than those in the East Asian subjects, with no significant difference between Southeast and South Asian subjects (Figure S1A). Additional analyses in subjects without habitual alcohol consumption showed results similar to those in Figure S1A (Figure S1B).

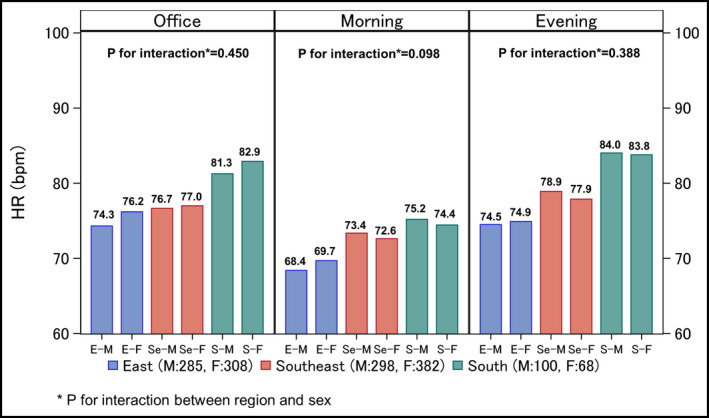

In the present study subjects, no significant difference in RHR between male and female subjects was observed for any region. In addition, the interaction between region and sex was not significant (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Regional and sex differences in resting heart rate. A multivariable linear regression model adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, habitual alcohol consumption, current smoking habit, shift worker, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, history of heart failure, and beta‐blocker intake was used to compare data among three Asian regions. The number shown above each bar chart is an estimated mean value. HR, heart rate. *P for interaction between region and sex

4. DISCUSSION

In the present analysis, we found significant differences in office and home RHRs among East, Southeast, and South Asia regions. Although BP levels were higher in Southeast Asia than in South Asia, higher RHRs were found in South Asia.

4.1. Regional difference in resting heart rate

In our study, both office and home RHRs showed significant differences among Asian regions. Although all the participants performed their home morning and home evening RHR measurements using the same device and protocol (details are described in the Methods section), the home morning and evening RHR values were higher in South Asia than in other regions. The increased RHR is known to be related to BP elevation and metabolic disturbances. 1 However, the elevation in heart rate and the elevation in blood pressure were not found in parallel in this study. The South Asian subjects were significantly younger and had higher BMI, higher incidence of diabetes and heart failure, higher frequency of smoking habits, drinking habits and beta‐blocker use, and more males. However, even after adjusting for these risk factors, regional difference in RHRs remained significant. Especially, a history of heart failure, treatment with beta‐blocker, and habitual alcohol consumption, that potentially affect heart rate, were much more frequently found in South Asian subjects compared to other regions. The analyses that excluded subjects with these factors produced the same results as those for all subjects, with the highest RHRs in South Asia. Interestingly, although the subjects with beta‐blocker treatment had lower RHRs than those without in East and Southeast Asia; this association was not found in South Asia. These results may suggest that the effect of beta‐blocker on heart rate is weak in South Asian population, which means that there is a racial difference in the effect of antihypertensive treatment. However, further research is needed to clarify these issues, because this is a cross‐sectional study.

Elevation in heart rate in hypertensive patients may be influenced by various factors such as population genetics, food, lifestyle, and climate. Physiologically, heart rate is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. A previous study comparing South Asians with Europeans have reported that South Asians had higher heart rate independent of insulin resistance and other factors and have indicated that altered sympathovagal balance contributed to the ethnic difference in heart rate and coronary disease risk. 13 In the present study, South Asians had the highest heart rate among East, Southeast, and South Asians. These results suggest that the contribution of the autonomic nervous system to the incidence of hypertension may differ among Asian regions and South Asian hypertensive patients might indicate increased sympathetic activation in balance with parasympathetic tone. Several cohort studies have demonstrated that increased heart rate precedes the development of hypertension. 14 , 15 Given these results, increased sympathetic tone may be a major factor in the pathophysiology of hypertension and subsequent cardiovascular disease in South Asians. The characteristics and prognostic impact of increased heart rate in Asians, especially South Asians, merits further study. In addition, the climates of the countries participating in this study are diverse. BP and heart rate might be affected by a combination of factors such as temperature, humidity, sunlight, season, and other factors. Further studies are needed to investigate the differences in BP and heart rate according to climate.

In our study subjects, no sex‐specific difference or region–sex interactions were observed. Some studies have suggested the existence of sex and racial differences in autonomic cardiovascular regulation. 8 , 16 The reason for this discrepancy is unclear from the present results. Our sample size may have insufficient analytical power. Alternatively, it may be that Asians do not have sex‐specific differences in RHR and sympathetic regulation. Further study is needed to determine the sex‐specific differences among Asian populations.

4.2. Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor

Numerous studies have shown that increased RHR was associated with overall and cardiovascular mortality, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and stroke 1 ; however, several studies have shown inconsistent results. 2 , 6 A meta‐analysis of two US studies enrolling black and white subjects and one cohort study in Finland found that increased RHR was associated with incident heart failure. 2 The BEAUTIFUL study in patients with stable coronary artery disease, of which 98% of total subjects were Caucasian, demonstrated that using ivabradine to reduce heart rate decreased the incidence of coronary artery disease outcomes but not of cardiac outcomes. 6 In addition, some studies have reported significant racial differences in RHR. 7 , 8 From these results, the aforementioned inconsistency among studies might be partly explained by racial differences and the severity of subjects’ concomitant cardiovascular risk. The Kailuan study, a prospective longitudinal cohort study from China, showed that elevated RHR was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and all‐cause death, but not all‐cause cardiovascular disease and stroke, 17 indicating that elevated RHR could be a prognostic risk factor, especially for coronary artery disease, in the Asian population. In addition, a study comparing multi‐ethnic groups living in Malaysia has shown that Indians had higher prevalence of coronary heart disease than Chinese and Malays, 18 and a study in Singapore has reported similar results. 19 Thus, even within the same country, different ethnicities might partly affect heart rate and coronary disease risk. Ueshima and colleagues reported the difference in mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease across countries of different regions of Asia. 20 East Asian countries have lower incidence and mortality from coronary heart disease than stroke, 21 whereas South Asian countries have lower incidence and mortality from stroke than coronary heart disease (Figure S2). In their study, South Asian countries showed higher coronary heart disease mortality than East and Southeast Asian countries. The difference in RHR among Asian regions found in our present study might contribute to the higher mortality rate of coronary heart disease in South Asian countries.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to compare self‐measured home heart rates using the same HBPM device and measurement protocol among broad regions of the Asian continent. Self‐measured home heart rate is advantageous for excluding the “white coat” effects of tension felt at the hospital or clinic. Measurement in sitting position is another advantage for self‐measured home heart rate. Heart rate varies in different body position 22 but ambulatory heart rate is usually measured in sitting, standing, and supine position. In addition, home heart rates averaged over 7–15 days of measurement are expected to be more reliable than a one‐time RHR measurement.

In the present study, we used resting heart rate in the same body position, sitting position.

This study also has some limitations. First, the sample size in each country/region was small. In particular, the number of subjects in South Asia was smaller than in the other two regions. Second, the hypertension stage and BP control status of study participants were not consistent. However, the present results do suggest that regional differences of RHR in Asia are independent of BP levels. Third, there are many different ethnic groups living in Southeast Asia, especially in Singapore; however, we did not collect information on the ethnicity of study patients. It should be considered the ethnicity of participants in the future Asian study. Finally, the study patients were enrolled from hypertension specialist centers; hence, it is unknown whether our results can be extended to the general population of Asia. Further studies with larger numbers of study subjects in the general population are needed to confirm the existence of regional differences in RHR across Asia.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The present analysis of the AsiaBP@Home study demonstrated the existence of regional differences in home RHR levels measured by the same HBPM device across Asia. If confirmed in a larger study including general populations, RHR might be identified as a convenient therapeutic target for preventing coronary heart disease in South Asia, in particular.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

CH Chen has received honoraria for serving as a speaker or member of a speaker bureau for AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck & Co, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Servier, and Takeda. YC Chia has received honoraria for serving as a speaker or advisor or to attend conferences and seminars from Boeringher‐Ingelheim, Pfizer, Omron, Servier, and Xepa‐Sol and an investigator‐initiated research grant from Pfizer and Omron. K Kario has received research grants from A&D Co., Bayer Yakuhin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, EA Pharma, Fukuda Denshi, Medtronic, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Omron Healthcare, Otsuka, Pfizer, Takeda, and Teijin Pharma; and honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Omron Healthcare, and Takeda. S Park has received honoraria from Astellas and Pfizer; and consultation fees from Takeda. S Siddique has received honoraria from Bayer, Novartis, Pfizer, ICI, and Servier; and travel, accommodation, and conference registration support from Hilton Pharma, Atco Pharmaceutical, Highnoon Laboratories, Horizon Pharma, and ICI. GP Sogunuru has received a research grant related to hypertension monitoring and treatment from Pfizer. JM Nailes has received honorarium and sponsorship to attend conferences and seminars from Pfizer and Omron, and received an investigator‐initiated research grant from Pfizer. JG Wang has received grants from Bayer, ChengDu DiAo, MSD, and Omron, and lecture and consulting fees from Astra‐Zeneca, Merck, Novartis, Omron, Servier, and Takeda. All other authors report no potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

N. Tomitani analyzed the data and wrote the Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections. S. Hoshide, P. Buranakitjaroen, YC. Chia, S. Park, CH. Chen, J. Nailes, J. Shin, S. Siddique, J. Sison, A. Soenarta, G. Sogunuru, J. Tay, Y. Turana, Y. Zhang, S. Wanthong, JG. Wang MD, and K. Kario collected data and discussed the results. N. Matsushita provided technical support. K. Kario supervised the conduct of the study and data analysis.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by an Investigator‐Initiated Research grant from Pfizer. In addition, Omron Healthcare provided the use of computer servers to store study‐related data. The protocol for the study was developed by Jichi Medical University School of Medicine. Pfizer and Omron were not involved in the development of the study protocol or the writing of this manuscript.

Tomitani N, Hoshide S, Buranakitjaroen P, et al; the HOPE Asia Network . Regional differences in office and self‐measured home heart rates in Asian hypertensive patients: AsiaBP@Home study. J Clin Hypertens. 2021;23:606–613. 10.1111/jch.14239

REFERENCES

- 1. Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Grassi G. Heart rate as a predictor of cardiovascular risk. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(3):e12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khan H, Kunutsor S, Kalogeropoulos AP, et al. Resting heart rate and risk of incident heart failure: three prospective cohort studies and a systematic meta‐analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(1):e001364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, et al. Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease and left‐ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9641):817‐821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hozawa A, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, et al. Prognostic value of home heart rate for cardiovascular mortality in the general population: the Ohasama study. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(11 Pt 1):1005‐1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bohm M, Mahfoud F, Townsend RR, et al. Ambulatory heart rate reduction after catheter‐based renal denervation in hypertensive patients not receiving anti‐hypertensive medications: data from SPYRAL HTN‐OFF MED, a randomized, sham‐controlled, proof‐of‐concept trial. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(9):743‐751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Ferrari R, Investigators B. Ivabradine for patients with stable coronary artery disease and left‐ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9641):807‐816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ostchega Y, Porter KS, Hughes J, Dillon CF, Nwankwo T. Resting pulse rate reference data for children, adolescents, and adults: United States, 1999–2008. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011;41:1‐16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colangelo LA, Yano Y, Jacobs DR Jr, Lloyd‐Jones DM. Association of resting heart rate with blood pressure and incident hypertension over 30 years in Black and White adults: The CARDIA Study. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):692‐698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kario K, Wang JG. Could 130/80 mm Hg be adopted as the diagnostic threshold and management goal of hypertension in consideration of the characteristics of Asian populations? Hypertension. 2018;71(6):979‐984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kario K, Tomitani N, Buranakitjaroen P, et al. Home blood pressure control status in 2017–2018 for hypertension specialist centers in Asia: results of the Asia BP@Home study. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20(12):1686‐1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kario K, Tomitani N, Buranakitjaroen P, et al. Rationale and design for the Asia BP@Home study on home blood pressure control status in 12 Asian countries and regions. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20(1):33‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takahashi H, Yoshika M, Yokoi T. Validation of three automatic devices for the self‐measurement of blood pressure according to the European Society of Hypertension International Protocol revision 2010: the Omron HEM‐7130, HEM‐7320F, and HEM‐7500F. Blood Press Monitor. 2015;20(2):92‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bathula R, Francis DP, Hughes A, Chaturvedi N. Ethnic differences in heart rate: can these be explained by conventional cardiovascular risk factors? Clin Auton Res. 2008;18(2):90‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Palatini P, Dorigatti F, Zaetta V, et al. Heart rate as a predictor of development of sustained hypertension in subjects screened for stage 1 hypertension: the HARVEST Study. J Hypertens. 2006;24(9):1873‐1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang A, Liu X, Guo X, et al. Resting heart rate and risk of hypertension: results of the Kailuan cohort study. J Hypertens. 2014;32(8):1600‐1605; discussion 1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farrell MC, Giza RJ, Shibao CA. Race and sex differences in cardiovascular autonomic regulation. Clin Auton Res. 2020;30(5):371‐379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang A, Chen S, Wang C, et al. Resting heart rate and risk of cardiovascular diseases and all‐cause death: the Kailuan study. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teh JK, Tey NP, Ng ST. Ethnic and gender differentials in non‐communicable diseases and self‐rated health in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee J, Heng D, Chia KS, Chew SK, Tan BY, Hughes K. Risk factors and incident coronary heart disease in Chinese, Malay and Asian Indian males: the Singapore Cardiovascular Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(5):983‐988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ueshima H, Sekikawa A, Miura K, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in Asia: a selected review. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2702‐2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang W, Jiang B, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: results from a nationwide population‐based survey of 480 687 adults. Circulation. 2017;135(8):759‐771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li FK, Sheng CS, Zhang DY, et al. Resting heart rate in the supine and sitting positions as predictors of mortality in an elderly Chinese population. J Hypertens. 2019;37(10):2024‐2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material