Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Vitamin C (500mg/day) supplementation for pregnant smokers has been reported to increase newborn pulmonary function and infant forced expiratory flows (FEFs) at 3 months of age. Its effect on airway function through 12 months of age has not been reported.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess whether vitamin C supplementation to pregnant smokers is associated with a sustained increased airway function in their infants through 12 months of age.

METHODS:

This is a prespecified secondary outcome of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that randomized 251 pregnant smokers between 13 to 23 weeks of gestation: 125 to 500 mg/day vitamin C and 126 to placebo. Smoking cessation counseling was provided. FEFs performed at 3 and 12 months of age were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of covariance.

RESULTS:

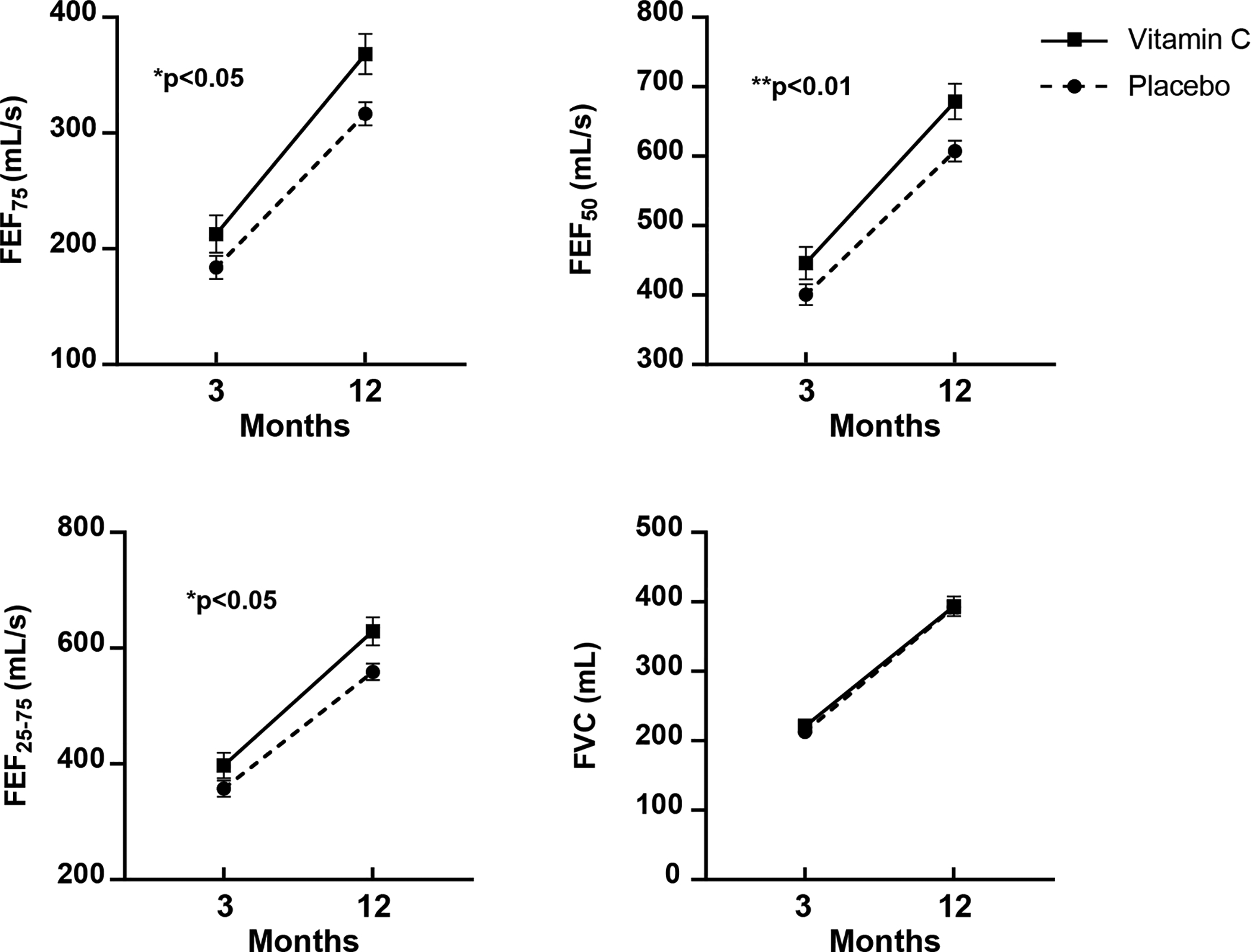

FEFs were performed in 222 infants at 3 months and 202 infants at 12 months of age. The infants allocated to vitamin C had significantly increased FEFs over the first year of life compared to those allocated to placebo. The overall increased flows were: 40.2 mL/sec for FEF75 (adjusted 95% CI for difference 6.6 to 73.8; p = 0.025); 58.3 mL/sec for FEF50 (95% CI 10.9 to 105.8; p= 0.0081); and 55.1 mL/sec for FEF25–75 (95% CI, 9.7 to 100.5; p=0.013).

CONCLUSIONS:

In offspring of pregnant smokers randomized to vitamin C versus placebo, vitamin C during pregnancy was associated with a small but significantly increased airway function at 3 and 12 months of age, suggesting a potential shift to a higher airway function trajectory curve. Continued follow-up is underway.

TRIAL REGISTRATION

Clinicaltrials.gov, Identifier: NCT01723696

INTRODUCTION

Absolute values of airway function increase with lung growth and development between infancy and early adulthood when maximal values are achieved, plateau, then progressively decline throughout adulthood.1 Longitudinal studies demonstrate that the trajectories for airway function are established early in life. Infants and children in the lower percentiles of airway function tend to have persistently lower function into adulthood.2, 3 Individuals with decreased airway function early in life may be at increased risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during adulthood as airway function declines.4

In-utero smoke exposure is a well-established risk factor for impaired fetal lung development, decreased airway function, and an increased risk for wheeze and asthma in the offspring.5, 6 Therefore, in-utero smoke exposure is an important determinant of a lifetime of decreased airway function and increased respiratory morbidity. At least 10% of women in the United States (US) smoke cigarettes while pregnant.7 A recent meta-analysis8 reported that worldwide > 50% of smokers who become pregnant continue to smoke. As smoking cessation interventions during pregnancy have not been very successful, this translates into a huge worldwide economic burden with no effective interventions.8 The growing use of e-cigarettes during pregnancy may only exacerbate this problem.9

We previously reported in a blinded, randomized, multi-center trial that vitamin C supplementation (500 mg/day) given to pregnant smokers unable to quit smoking caused significant increases in their offspring’s newborn pulmonary function tests performed within 72 hours of birth, and decreased the incidence of wheeze through 12 months of age.10 We recently completed a second separate multi-center randomized controlled trial and reported results at 3 months of age.11 We now report the airway function tests from this second trial through 12 months of age. We hypothesized that vitamin C supplementation to pregnant smokers would be associated with a persistent increase in the airway function in their infants through 12 months of age. Some of the results of these studies were previously reported.11,12

METHODS

Population and Study Protocol

Surviving infants born to pregnant smokers enrolled in the VCSIP study conducted in the US between 2012 and 2016 were eligible for the measurement of airway function/ forced expiratory flows (FEFs) at 3 and 12 months of age. This study protocol has been described.13 Briefly, this double blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial enrolled smokers (≥ 1 cigarette in the last week) pregnant between 13 to 23 weeks with a singleton gestation. They were randomized to vitamin C (500 mg/day) versus placebo after successful completion of a medication adherence period that required 75% adherence and return for an appointment between 7 and 21 days later. Study medication was prepared in organoleptically identical capsules (Magno-Humphries Laboratories Inc, Tigard, Oregon) and distributed through the clinical sites’ research pharmacies. Brief smoking cessation counseling was provided to all participants beginning at screening and at every visit thereafter for the duration of the study. Randomization was blocked in rotations of two and four subjects, and stratified by gestational age (≤18 versus >18 weeks) and site (Oregon Health & Science University [OHSU], Portland, Oregon; PeaceHealth Southwest Washington Medical Center [SWW], Vancouver, Washington; Indiana University [IU], Indianapolis, Indiana). The OHSU data coordinating center performed randomization.

After randomization, all women met with study staff at each prenatal visit to assess medication use by pill count, smoking status, and any health change. Staff trained in smoking cessation provided a pregnancy specific smoking cessation pamphlet and provided brief cessation counseling consistent with the U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline.13 Serial biomarkers of fasting maternal blood for ascorbic acid (a measure of medication compliance)11 and urine for cotinine levels were collected at randomization and mid and late gestation.

The trial was approved by each hospital’s Institutional Review Board and monitored by an NIH appointed Data Safety Monitoring Board. Written informed consent was obtained from pregnant smokers before enrollment.

Follow-up, Secondary Outcomes: Study Procedures and Outcomes

We have previously reported the primary outcome of the trial, showing that FEF75 (the measurement of FEF at 75% of the expired volume), at 3 months of age in the infants born to pregnant smokers randomized to vitamin C versus placebo tended to be higher in the vitamin C group, although it did not meet statistical significance.11 However the predefined secondary outcomes of FEF50 (FEF at 50% of expired volume), and FEF25–75 (FEF between 25% and 75% expired volume) obtained from the same expiratory curves as the FEF75 were significantly increased in the vitamin C versus placebo treated infants. We are now reporting on sustained changes in FEFs between the vitamin C and placebo groups in the first year of life measured at 3 and 12 months of age and the incidence of wheeze through 12 months of age. These measurements were completed between 2013 and 2016.

Infant Airway Function Tests at 3 and 12 Months of Age

Infant FEFs were performed at each site with identical equipment (Jaeger/Viasys Master Screen BabyBody; Yorba Linda, California) after chloral hydrate sedation following a standardized protocol.14,15 Testing occurred at least three weeks after a respiratory illness. The 3-month test results were included if performed within the predetermined infant age of 10 to 26 weeks; the 12-month test results were included if performed within 43 to 65 weeks of infant age. All tests were reviewed for acceptability, reproducibility, and completeness.

FEFs were obtained from forced expiratory flow volume curves using the raised volume rapid thoracic compression technique following the American Thoracic Society/ European Respiratory Society criteria for performance and acceptance.14 Briefly, the lung was inflated with a pressure of 30 cm H2O to the airway with a face mask. An inflatable jacket initiated thoracic compression at this raised volume and was maintained until residual volume was reached. Forced expiratory maneuvers were repeated with increased pressure until flow limitation was obtained. Once flow limitation was established, the maneuver was repeated over a 10 to 15 cm H2O range in jacket pressure until three technically acceptable curves were obtained with FEF25–75 and FVC (forced vital capacity) within 10%. The best trial was chosen, determined as the most reliable with smooth forced expiration without evidence of early inspiration, marked flow transients, or glottic closure.14, 15

Respiratory Questionnaires/Incidence of Wheeze

To compare the incidence of wheeze, a respiratory questionnaire (RQ) modified from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood questionnaire16–18 was administered at least quarterly to the infant’s caretaker. Presence or absence of wheeze, medications for wheeze, postpartum maternal smoking, and other exposures were assessed. Composite wheeze was defined as a positive response to any of the following: parental report of wheeze, healthcare provider diagnosis of wheeze, any bronchodilator or steroids use. As defined a priori, only patients with at least 1 RQ completed at ≥ 4 months of age were included in the clinical outcomes analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data are summarized as means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. These analyses are all pre-planned secondary analyses and the power calculation was created for the primary analysis.

A linear, mixed-model (with random intercepts), repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed for FEF75, FEF50, FEF25–75, FVC, FEV0.5 (forced expired volume in the initial 0.5 sec), and FEV 0.5/FVC. This model included a full-factorial analysis of the design variables for the study: stratification for gestational age at randomization andclinical site, visit (3 and 12-month test), and the randomization group (vitamin C or placebo). The model also included three covariates (sex, white/non-white, and standardized infant length at testing) as well as their interactions. These covariates were specified a priori (in the protocol) as these covariates are known predictors of FEFs and potentially different among the sites. As length at test vist is collinear with visit, lengths were standardized to a z-score.14,15 Least squares (or adjusted means) and associated 95% CIs were estimated for significant terms in the ANCOVA model. Z-scores for airway function tests were derived using equations from Lum et al.19

Logistic regression modeling was used for analysis of wheeze outcomes adjusting for treatment arm, clinical site, and gestational age at randomization (and all two-factor interactions of these three factors) and the covariates of infant sex and maternal race. Sample sizes did not permit additional interactions. Additional covariates were considered by adding to the initial design model one at a time without interactions and evaluated with respect to model fit and odds ratio for group.

All p-values are 2-sided with significance set at p<0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Patients

We randomized 252 pregnant smokers, however one subject was excluded due to a protocol violation, so 251 were randomized to receive vitamin C or placebo and their infants were followed through 12 months of age (Figure 1). Of the 243 infants at delivery, 241 survived to 12 months of age with one infant death per group (both presumed sudden infant death syndrome). Two hundred and twenty-five infants (93%) attempted FEFs at 3 months of age and 222 (99%) were technically acceptable; 213 (88%) attempted FEFs at 12 months of age with 202 (95%) technically acceptable. Supplement Table1A and 1B contain information on characteristics of patients with complete versus incomplete FEF data. Ninety-eight percent of surviving infants, or 237, had at least one RQ completed at ≥ 4 months of age. The median number of RQs completed was 9.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram for Randomized Smokers.

Enrollment, randomization, and follow-up of randomized smokers and their infants through the 3 and 12 month measurements of airway function / forced expiratory flows (FEFs). In addition, 237 of the infants had respiratory questionnaires completed as per protocol.

The baseline characteristics of the mothers of the infants with completed respiratory clinical outcome data were similar between the vitamin C and placebo treated groups (Table 1) including indicators of smoking status, fasting randomization ascorbic acid level, and other factors that influence offspring respiratory outcomes such as maternal asthma and body mass index (BMI).20 The median number of cigarettes smoked/day was: 7 in both groups at randomization; 6 in the placebo versus 5 in the vitamin C group at midgestation; 5 in each group at late gestation. Women allocated to vitamin C treatment versus placebo had significantly higher fasting ascorbic acid levels at mid (60.8 vs 41.6 μmol/L; p<0.001) and late gestation (54.6 vs 39.6 μmol/L; p<0.001).

Table 1.

Population Characteristics of Infants with Completed Respiratory Clinical Outcomes and their Mothersa

| Vitamin C Treated (n=118) |

Placebo Treated (n=119) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Maternal Characteristics at Randomization | |||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 26.6 (5.3) | 26.4 (5.9) | |

| White, n (%) | 93/118 (78.8%) | 95/119 (79.8%) | |

| Gravida, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) kg/m2 | 27.2 (24.4–31.5) | 29.3 (24.5–34.7) | |

| Married, n (%) | 21/118 (17.8%) | 31/119 (26.1%) | |

| History of asthma, n (%) | 39/118 (33.1%) | 37/119 (31.1%) | |

| Some college, n (%) | 44/118 (37.3%) | 52/119 (43.7%) | |

| Private health insurance, n (%) | 13/118 (11.0%) | 18/119 (15.1%) | |

| Gestational age, mean (SD), weeks | 18.5 (3.0) | 18.2 (2.8) | |

| Maternal cigarettes/day during pregnancy, median (IQR) | 7.0 (4.0–10.0) | 7.5 (4.0–10.0) | |

| Urine cotinine, median (IQR), ng/mL | 5031.1 (1788.7–7264.0) | 5334.2 (1933.0–8291.0) | |

| Plasma ascorbic acid, mean (SD), μmol/L | 49.2 (19.1) | 48.7 (19.3) | |

| Birth Characteristics of Infants who Completed Respiratory Clinical Outcomes | P value | ||

| Birth weight, mean (SD), grams | 3127 (517) | 3067 (557) | 0.39 |

| Birth weight z-scores, mean (SD) | −1.0 (0.7) | −1.1 (0.9) | 0.12 |

| Gestational age, mean (SD), weeks | 38.7 (1.8) | 38.6 (1.7) | 0.64 |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 40/118 (33.9%) | 34/118 (28.8%) | 0.31 |

| Female, n (%) | 57/118 (48.3%) | 60/119 (50.4%) | 0.74 |

| Preterm, <37 weeks gestation, n (%) | 14/118 (11.9%) | 11/119 (9.2%) | 0.51 |

| Intrauterine growth restriction, n (%) | 1/118 (0.8%) | 4/119 (3.4%) | 0.18 |

| Postnatal Characteristics of Infants with Completed Respiratory Clinical Outcomes | |||

| Maternal cigarettes/day at 3 month RQ, median (IQR) | 8.0 (5.0–10.0) | 9.5 (5.0–10.0) | 0.34 |

| Maternal cigarettes/day at 12 month RQ, median (IQR) | 8.0 (4.0–10.0) | 8.0 (3.0–10.0) | 0.82 |

| Breastfed at 3 month RQ (%) | 42/117 (35.9%) | 40/116 (34.5%) | 0.82 |

| Breastfed at 12 month RQ (%) | 14/116 (12.1%) | 20/119 (16.8%) | 0.30 |

| Daycare at 3 month RQ (%) | 6/117 (5.1%) | 5/116 (4.3%) | 0.77 |

| Daycare at 12 month RQ (%) | 15/116 (12.9%) | 16/119 (13.4%) | 0.91 |

| Pets in home in first year (%) | 79/118 (66.9%) | 79/119 (66.4%) | 0.93 |

| Diagnosis of eczema by physician (%) | 25/118 (21.2%) | 18/119 (15.1%) | 0.23 |

| Diagnosis of food allergy (%) | 12/118 (10.2%) | 12/119 (10.1%) | 0.98 |

Definition of abbreviations: SD= standard deviation; IQR= interquartile range; RQ= respiratory questionnaire;

This includes infants who had at least one respiratory questionnaire completed at ≥ 4 months of age.

The delivery characteristics of the infants were similar between randomized groups. Postnatal factors affecting infant respiratory health were comparable between groups including postnatal maternal smoking, incidence of breast feeding and daycare attendance (Table 1).

Airway Function Outcomes

The infants in the two treatment groups were not different in age, length, length z- scores, or respiratory rate at the 3 and 12-month tests (Supplement Table 2). The adjusted means for measurements of all of the airway function parameters at the 3 and 12 month evaluations are summarized in Table 2. All measurements increased between 3 and 12 months of age. For all measurements except FVC and FEV0.5/FVC, offspring of women allocated to vitamin C compared to placebo had on average significantly higher flows through the first year of life (Figure 2). There were no significant interactions for treatment group by study visit (3 and 12-month), suggesting effectively parallel differences between the treatment groups. These adjusted least square means were all significantly different from zero indicating that infants in the vitamin C group had improved FEFs over the 3 and 12-month visits: FEF75 of 40.2 mL/sec (adjusted 95% CI 6.6, 73.8); FEF50 of 58.3 mL/sec (10.9, 105.8); FEF25–75 of 55.1 mL/sec (9.7, 100.5); and FEV0.5 of 16 mL (1.0, 31.6). These effective percent increases with vitamin C compared to placebo were 16.1% for FEF75, 11.6% for FEF50, 12% for FEF25–75, and 6.8% for FEV0.5.. There were significant higher-order interactions that included both treatment group and visit for all airway function parameters except FEF75. However, there were no differences between treatment groups for any combination of the other design variables supporting the use of the overall mean differences between the treatment groups above. More detailed analyses summaries are provided in Supplement Table 3A and 3B. Our statistical analysis plan also contained a predefined analysis of FEFs at 3 months (previously reported11) and at 12 months in addition to the repeated measures analysis. The stand-alone analysis of FEFs at 12 months also showed a significantly increased FEF75, FEF50, and FEF25–75 at 12 months with maternal vitamin C treatment (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 2.

Airway Function Tests in Infants at Three and Twelve Month Visits

| Vitamin C treated at 3 months (n=113) |

Vitamin C treated at 12 months (n=101) |

Overall values in Vitamin C treated | Placebo treated at 3 months (n=109) |

Placebo treated at 12 months (n=101) |

Overall values in placebo treated | Adjusted P value for overall difference between vitamin C versus placebo groupsb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEF75 (mL/sec) | 213 (16) | 368 (17) | 290 (15) | 184 (10) | 317 (10) | 250 (8) | 0.025 |

| FEF50 (mL/sec) | 446 (23) | 679 (26) | 562 (21) | 401 (15) | 607 (15) | 504 (12) | 0.0081 |

| FEF25–75 (mL/sec) | 397 (22) | 629 (24) | 513 (20) | 357 (14) | 559 (14) | 458 (11) | 0.013 |

| FEV0.5 (mL)a | 191 (7) | 320 (8) | 256 (7) | 174 (5) | 305 (5) | 239 (4) | 0.014 |

| FVC (mL) | 229 (10) | 401 (11) | 315 (10) | 212 (7) | 392 (7) | 302 (5) | 0.13 |

| FEV0.5 / FVCa | 0.845 (0.015) | 0.812 (0.016) | 0.829 (0.014) | 0.828 (0.009) | 0.782 (0.009) | 0.805 (0.007) | 0.11 |

All values are adjusted means (standard error of the mean). Abbreviations: FEF= forced expiratory flow; FEF75 =the measurement of FEF at 75% of the expired volume; FEF50 = FEF at 50% of expired volume; FEF25–75 = FEF between 25 and 75% of expired volume; FEV0.5= forced expired volume in the initial 0.5 seconds; FVC = forced vital capacity.

The infants in the two treatment groups were not different in age, length, or length z scores at 3 or 12 month tests.

One infant in the vitamin C group at the 3-month visit did not have an FEV0.5 value (or corresponding ratio) reducing the sample sizes in these tests by one.

Adjusted P value represents significantly improved FEF75, FEF50, FEF25–75, FEV0.5 for vitamin C versus placebo through 12 months of age. Adjusted P-values were estimated using mixed-model repeated measures analysis of covariance models that include treatment group, visit, other design variables (site and gestation age at randomization), and potential covariates (gender, white/non-white, and standardized length at testing). Please see text for details. While there were significant interactions involving treatment group for each airway function measure other than FEF75, there was no evidence that these interactions modified the overall difference between the treatment groups. That is, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups for any combination of the other variables in the interaction terms. For example, if the interaction between gestational age (GA) and treatment group were significant, the difference between the two treatment groups was not significant for either the children with earlier GA or the children with later GA.

Figure 2. Effect of Vitamin C Supplementation During Pregnancy on Infant Airway Function Tests at 3 and 12 Months of Age.

Plots of unadjusted means (expressed as Means ± SEM) for FEF75 (the measurement of FEF at 75% of the expired volume), FEF50 (FEF at 50% of expired volume), FEF25–75, (FEF between 25 and 75% of expired volume), FVC (forced vital capacity). Vitamin C treated is solid line, closed square and placebo is dotted line, closed circle. FEF75, FEF50, and FEF25–75, were significantly improved in the vitamin C versus placebo group through 12 months of age by repeated measures analysis of covariance. There were no significant interactions for treatment group by study visit (3 and 12-month), suggesting effectively parallel differences between the treatment groups. See Table 2 legend and text.

Clinical Respiratory Outcomes

Clinical RQ follow-up was obtained in 98% of the infants who survived from delivery to 12 months of age. There were no differences at baseline between the intervention groups in maternal or infant characteristics or postnatal factors known to influence wheeze (Table 1). The overall incidence of composite wheeze was 51/118 (43.2%) in the vitamin C and 63/119 (53.9%) in the placebo group (unadjusted p=0.13).

Treatment group allocation was significant (p=0.03) in the overall multivariable analysis, as were study site (p=0.03) and sex (p=0.03). However there were significant interactions between treatment group and study site on the incidence of wheeze (p=0.03) as well as between treatment group and gestational age at randomization (p=0.004) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence of Wheeze by Recruitment Site and Gestational Age Stratification

| Vitamin C n=118 | Placebo n=119 | OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomization Strata | |||

| PeaceHealth Southwest Washington Medical Center (SWW) | |||

| Gestational age ≤18 weeks | 6/24 (25%) | 22/28 (78.6%) | 0.16 (0.06, 0.44) |

| Gestational age >18 weeks | 15/30 (50%) | 12/27 (44.4%) | 0.82 (0.32, 2.10) |

| Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) | |||

| Gestational age ≤18 weeks | 1/9 (11.1%) | 6/12 (50%) | 0.095 (0.02, 0.51) |

| Gestational age >18 weeks | 2/11 (18.2%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 0.50 (0.10, 2.60) |

| Indiana University (IU) | |||

| Gestational age ≤18 weeks | 8/16 (50%) | 7/17 (41.2%) | 0.62 (0.20, 1.92) |

| Gestational age >18 weeks | 19/28 (67.9%) | 13/27 (48.2%) | 3.30 (1.23, 8.93) |

Logistic regression modeling was used for analysis of wheeze outcomes adjusting for treatment arm, clinical site, and gestational age at randomization (and all two-factor interactions of these three factors) and the covariates of infant sex and maternal race.

At SWW, the odds ratio (OR) of wheeze was 0.16 (95% CI 0.06, 0.44) in infants of pregnant smokers taking vitamin C started at ≤ 18 weeks gestation versus placebo. Similarly, at OHSU, the OR was 0.095 (95% CI 0.02, 0.51). Yet at IU, the OR of wheeze was 3.30 (95% CI 1.22, 8.93) when vitamin C was begun at > 18 weeks gestational age.

The ORs for the other three combinations of site and gestational age were not statistically significant. Adding maternal asthma and BMI as potential covariates did not explain the differences in treatment effect between centers. Male gender and maternal asthma were associated with increased risk of wheeze. When the analysis was repeated using health care provider diagnosis of wheeze or use of asthma medication the results were similar.

Adverse Events

No serious adverse events were related to the intervention.

DISCUSSION

This is the first randomized controlled trial to demonstrate a persistent increase in infant airway function after an in-utero intervention targeted to block a specific environmental insult known to adversely affect subsequent childhood respiratory health. In this study of singleton infants of pregnant smokers randomized at <23 weeks of gestation to receive vitamin C supplementation (500 mg/day) or placebo for the remainder of the pregnancy, vitamin C produced a persistently significant increase of the offspring’s airway function at 3 and 12 months of age. The results of this study, as well as our previous clinical trial in newborns10 cumulatively demonstrate vitamin C improves lung function at birth and these improvements are maintained throughout the first year of life.

Data from longitudinal birth cohorts demonstrate that an individual’s airway function is established very early in infancy and subsequently tracks over time,3, 21 although there may be some potential for improvement between infancy and childhood.22 This study is the first to provide evidence that these parameters can be reset with targeted prenatal interventions yielding changes in the first year of life, and potentially shifting airway function to a higher percentile on the trajectory curve.1 In the current study, FEFs in the vitamin C treated group were increased by 11.6% to 16.1% compared to placebo, which is consistent with differences in the newborn pulmonary function tests assessed in our first trial.10 It is also consistent with percent decreases that we23 and others24,25 have reported in infants born to smokers versus nonsmokers, which was the basis for the power calculations of sample size for the differences in the three month FEFs in the current study.23 The summary statistics of the z-scores19 of the FEFs of the vitamin C and placebo treated infants indicate their flows fall within normal limits and are consistent with the statistical analyses of the raw values (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary Table of z-Scores for Airway Function Tests at 3 and 12 Months of Age

| Vitamin C treated at 3 Months of Age (n=113) |

Placebo treated at 3 Months of Age (n=109) |

Vitamin C treated at 12 Months of Age (n=101) |

Placebo treated at 12 Months of Age (n=101) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEF75, mL/sec | −0.02 (1.37) | −0.24 (1.33) | 0.62 (0.95) | 0.32 (1.16) |

| FEF25–75, mL/sec | 0.29 (1.18) | 0.02 (1.29) | 0.77 (1.00) | 0.46 (1.11) |

| FEV0.5, mL | −0.01 (1.07) | −0.24 (1.16) | 0.30 (0.96) | 0.20 (1.13) |

| FVC, mL | −0.28 (1.12) | −0.39 (1.29) | −0.18 (0.96) | 0.09 (1.02) |

| FEV0.5/FVC | 0.28 (0.98) | 0.10 (1.13) | 0.82 (0.95) | 0.53 (0.95) |

Definition of abbreviations: FEF75 = forced expiratory flow at 75% of the expired volume; FEF 25–75 =forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of the expired volume; FEV 0.5 = forced expired volume in the initial 0.5 seconds; FVC= forced vital capacity;

The persistence in the difference in FEFs for the vitamin C versus placebo did not change over time; specifically, there was not a significant interaction of treatment and time indicating that the protective effect of vitamin C on FEFs appeared constant throughout the first 12 months of life. This is consistent with our preclinical non-human primate data demonstrating that nicotine crosses the placenta and upregulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. While the exact mechanism of action is unknown, nicotine treatment in this model was associated with collagen deposition around the airways and decreased FEFs in the offspring.26–28 Vitamin C supplementation during nicotine exposure in pregnancy blocked these structural changes,29 which could explain the persistently higher FEFs through 12 months of age we observed in the current study of human infants. The vitamin C treatment may also be acting through antioxidant mechanisms to prevent nicotine’s ability to alter airway geometry in favor of smaller diameter airways.30 The actions of vitamin C on airway geometry, connective tissue, and alveolar structure likely underlies why vitamin C treatment effects FEF’s but not overall lung volumes.

Improved airway function in infants has been associated with a lower incidence of wheeze early in life.31,32 Although vitamin C produced a persistent increase in FEFs at all study sites, we did not find that the incidence of wheeze was significantly lower across all study sites. Therefore, it becomes difficult to interpret the magnitude of the effect size of improved FEFs upon the clinical outcome of decreased wheeze. Composite wheeze was 43.2% for the vitamin C treated and 53.9% for the placebo treated group. This difference was not statistically significant across all sites and gestational age groups. Interpretation of the clinical assessment of wheeze is complex as there were significant interactions for treatment, site, and gestational age. The decrease in the incidence of wheeze in the vitamin C treated group in the combined OHSU and SWW sites in the current study (32% in the vitamin C and 57% in the placebo for a 44% decrease) was consistent with the decrease reported in our first study10 at these same sites (21% in the vitamin C and 40% in the placebo for a 48% decrease; p=0.03). However, in the current study, at the IU site, the incidence of wheeze in the vitamin C treated group was not lower than the placebo group. There was a higher incidence of pregnant smokers with a history of asthma (32% vs 11%), a higher incidence of infants with eczema (52% vs 23%) allocated to the vitamin C group in Indiana; however, secondary analysis using these covariates did not adequately account for site differences.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of our study is the assessment of FEFs, the gold standard for assessing intra-thoracic airway function in cooperative children and adults.33 Additional strengths include the small loss to follow-up, the significantly increased ascorbic acid levels in women randomized to vitamin C providing biologic support for the intervention,10 and the use of standardized RQs.16 The increased FEFs in the vitamin C treated groups were consistent across all 3 sites regardless of the gestational age at the initiation of intervention, supporting the generalizability of our findings, though the primary outcome of the study FEF75 at 3 months of age was not significantly different between groups.11 While there was a higher proportion of infants from Indiana with missing 3 month and 12 month outcome data; the strong correlation between site and non-white race in this trial needs additional study to determine if this effect is seen across all populations. Despite the pattern of missingness, there was no significant effect of site or race on the effect of vitamin C on FEFs in the formal statistical model.

Wheeze is a complex clinical respiratory outcome, particularly for infants who often have upper respiratory infections. Non-atopic and atopic mechanisms can contribute to airways obstruction and wheeze,34,35 and vitamin C supplementation may only affect some of the mechanisms. Both groups of pregnant smokers reported a comparable decrease in the median number of cigarettes smoked over the pregnancy which may have decreased the impact of vitamin C. In addition, we were likely underpowered for wheeze which was a secondary clinical outcome of the study. Vitamin C supplementation was also not continued postnatally, which might provide additional protection for growing airways exposed to postnatal smoking. Lastly, 12 months of age is a short period of follow-up for respiratory symptoms. These infants are now in continued follow-up through 5 years of age.

Conclusions

In this analysis of predefined secondary outcomes of a randomized clinical trial of vitamin C supplementation (500 mg/day) to pregnant smokers, vitamin C significantly increased the airway function in the infants through 12 months of age. While smoking cessation in pregnancy remains the number one priority and vitamin C supplementation does not justify continued smoking, in reality 50% of pregnant smokers continue to smoke despite vigorous antismoking campaigns.36,37 This study demonstrates that the safe, inexpensive,38 and simple intervention of vitamin C supplementation can persistently improve the airway function of infants exposed to in-utero smoke.

Supplementary Material

Take Home Message:

Vitamin C supplementation coupled with smoking cessation counseling for pregnant smokers may be a safe, inexpensive, and simple intervention to improve the airway function of their offspring through 12 months of age.

Acknowledgements:

The VCSIP research team deeply thanks the women and their infants who participated in our study. The VCSIP team also thanks and acknowledges the members of the Vitamins for Early Lung Health (VITEL) DSMB for their advice, support, and data monitoring during the trial.

Funding:

Supported by the NHLBI (R01 HL105447 and R01 HL 105460) with cofunding from the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) and by P51 OD011092565 and NIH UH3 OD023288. Additional support from the Oregon Clinical Translational Research Institute funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000128).

Footnotes

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournal.org

Reference List

- (1).Agusti A, Faner R. Lung function trajectories in health and disease. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7:358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Svanes C, Sunyer J, Plana E, Dharmage S, Heinrich J, Jarvis J, deMarco R, Norback D, Raherison C, Villani S, Wjst M, Svanes K, Anto JM. Early life origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2010;65(1):14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Stern DA, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, Guerra S, Martinez FD. Poor airway function in early infancy and lung function by age 22 years: a non-selective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2007;370(9589):758–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Martinez FJ, Han MK, Allinson JP, Barr RG, BOucher RC, Calverley PMA, Celli BR, Christenson SA, Crystal RG, Fageras M, Freeman CM, Groenke L, Hoffman EA, Kesimer M, Kstikas K, Paine R, Rafi S, Rennard SI, Segal LN, Shaykhiev R, Stevenson C, Tal-Singer R, Vestbo J, Woodruff PG, Curtis JL, Wedzchia JA. At the root: defining and halting progression of early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197(12):1540–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Best D. From the American Academy of Pediatrics: Technical report--Secondhand and prenatal tobacco smoke exposure. Pediatrics 2009;124(5):e1017–e1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Neuman A, Hohmann C, Orsini N, Pershagen G, Eller E, Kjaer JF, Gehring U, Granell R, Henderson J, Heinrich J, Lau S, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Sunyer J, Tischer C, Torrent M, Wahn U, Wijga AH, Keil T, Bergstrom A. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and asthma in preschool children: a pooled analysis of eight birth cohorts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186(10):1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D’Angela DV, Farr SL, TOckhill KM, England LJ. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy--Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2013;62(6):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lange S, Probst C, Rehm J, Popova S. National, regional, and global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6(7):e769–e776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Spindel ER, McEvoy CT. The role of nicotine in the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on lung development and childhood respiratory disease. Implications for dangers of e-cigarettes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193(5):486–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).McEvoy CT, Schilling D, Clay N, Jackson K, Go MD, Spitale P, Bunten C, Leiva M, Gonzales D, Hollister-Smith J, Durand M, Frei B, Buist AS, Peters D, Morris CD, Spindel ER. Vitamin C supplementation for pregnant smoking women and pulmonary function in their newborn infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311(20):2074–2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).McEvoy CT, Shorey-Kendrick LE, Milner K, Schilling D, Tiller C, Vuylsteke B, Scherman A, Jackson K, Haas DM, Harris J, Schuff R, Park BS, Vu A, Kraemer DF, Mitchell J, Metz J, Gonzalez D, Bunten C, Spindel Er, Tepper RS, Morris CD. Oral vitamin C (500 mg/day) to pregnant smokers improves infant airway function at 3 months (VCSIP): A randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199:1139–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).McEvoy CT, Milner KF, Schiling DG, Scherman A, TIller A, Buylsteke B, Jackson K, Haas D, Bunten C, Harris J, Vu A, Schuff R, Kraemer D, Mitchell J, Metz J, Shorey-Kendrick L, Spindel ER, Tepper RS, Morris CD. Improved forced expiratory flows in infants of pregnant smokers randomized to daily vitamin C versus placebo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018:A4192. [Google Scholar]

- (13).McEvoy CT, Milner KF, Scherman AJ, Schilling DG, TIller CJ, Vuylsteke B, Shorey-Kendrick LE, Spindel ER, Schuff R, Mitchell J, Peters D, Metz J, Haas D, Jackson K, Tepper RS, Morris CD. Vitamin C to Decrease the Effects of Smoking in Pregnancy on Infant Lung Function (VCSIP): Rationale, design, and methods of a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy for the primary prevention of effects of in utero tobacco smoke exposure on infant lung function and respiratory health. Contemp Clin Trials 2017;58:66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).ATS/ERS statement: raised volume forced expirations in infants: guidelines for current practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172(11):1463–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Jones MH, Davis SD, Grant D, Christoph K, Kisling J, Tepper RS. Forced expiratory maneuvers in very young children. Assessment of flow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159(3):791–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society). Am Rev Respir Dis 1978;118(6 Pt 2):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Litonjua AA, Lange NE, Carey VJ, Brown S, Laranjo N, Harshfield BJ, O’Connor GT, Sandel M, Strunk RC, Bacharier LB, Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Hollis BW, Weiss ST. The Vitamin D Antenatal Asthma Reduction Trial (VDAART): rationale, design, and methods of a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy for the primary prevention of asthma and allergies in children. Contemp Clin Trials 2014;38(1):37–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hibbs AM, Ross K, Kerns LA, Wagner CL, Fuloria M, Groh-Wargo S, Zimmerman T, Minich N, Tatsuoka C. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on recurrent wheezing in black infants who were born preterm: The D-Wheeze randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;319 (20):2086–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lum S, Bountziouka V, Wade A, Hoo AF, Kirby J, Moreno-Galdo A, et al. New reference ranges for interpreting forced expiratory manoeuvres in infants and implications for clinical interpretation: a multicentre collaboration. Thorax 2016; 71:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).MacDonald KD, Vesco KK, Funk KL, Donovan J, Nguyen T, Chen Z, Lapidus JA, Stevens VJ, McEvoy CT. Maternal body mass index before pregnancy is associated with increased bronchodilator dispensing in early childhood: A cross-sectional study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2016;51(8):803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Friedrich L, Pitrez PM, Stein RT, Goldani M, Tepper R, Jones MH. Growth rate of lung function in healthy preterm infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176(12):1269–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Belgrave DCM, Granell R, Turner SW, Curtin JA, Buchan IE, LeSouef PN, Simpson A, Henderson AJ, Custovic A. Lung function trajectories from pre-school age to adulthood and their associations with early life factors: a retrospective analysis of three population-based birth cohort studies. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6 (7): 526–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Jones M, Castile R, Davis S, Kisling J, Filburn D, Flucke R, Goldstein A, Emsley C, Ambrosius W, Tepper RS. Forced expiratory flows and volumes in infants. Normative data and lung growth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161(2 Pt 1):353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hanrahan JP, Tager IB, Segal MR, Tosteson TD, Castile RG, Van Vunakis J, Weiss ST, Speizer FE. The effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on early infant lung function. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145(5):1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Hayatbakhsh MR, Sadasivam S, Mamun AA, Najman JM, O’callaghan MJ. Maternal smoking during and after pregnancy and lung function in early adulthood: A prospective study. Thorax 2009;64(9):810–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Raab R, Kuryatov A, Pankow JF, Whitsett JA, Lindstrom J, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine increases pulmonary alpha7 nicotinic receptor expression and alters fetal lung development in monkeys. J Clin Invest 1999;103(5):637–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sekhon HS, Keller JA, Benowitz NL, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters pulmonary function in newborn rhesus monkeys. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164(6):989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Sekhon HS, Keller JA, Proskocil BJ, Martin EL, Spindel ER. Maternal nicotine exposure upregulates collagen gene expression in fetal monkey lung. Association with alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26(1):31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Proskocil BJ, Sekhon HS, Clark JA, Lupo SL, Jia Y, Hull WM, Whitsett JA, Starcher BC, Spindel ER. Vitamin C prevents the effects of prenatal nicotine on pulmonary function in newborn monkeys. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:1032–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wongtrakool C, Wang N, Hyde DM, Roman J, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters lung function and airway geometry through α7 nicotininc receptors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;46:695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Haland G, Carlsen KC, Sandvik L, Devulapalli CS, Munthe-Kaas MC, Pettersen M, Carlsen KH. Reduced lung function at birth and the risk of asthma at 10 years of age. N Engl J Med 2006;355(16):1682–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Martinez FD, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, Holberg C, Taussig LM. Initial airway function is a risk factor for recurrent wheezing respiratory illnesses during the first three years of life. Group Health Medical Associates. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;143(2):312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Rosenfeld M, Allen J, Arets BH, Aurora P, Beydon N, Calogero C, Castile RG, Davis SD, Fuchs S, Gappa M, Gustaffson PM, Hall GL, Jones MH, Kirkby JC, Kraemer R, Lombardi E, Lum S, Mayer OH, Merkus P, Nielsen KG, Oliver C, Oostveen E, Ranganathan S, Ren CL, Robinson PD, Seddon PC, Sly PD, Sockrider MM, Sonnappa S, STocks J, Subbarao P, Tepper RS, Vilozni D. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: optimal lung function tests for monitoring cystic fibrosis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and recurrent wheezing in children less than 6 years of age. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013;10(2):S1–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ly NP, Gold DR, Weiss ST, Celedon JC. Recurrent wheeze in early childhood and asthma among children at risk for atopy. Pediatrics 2006;117(6):e1132–e1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Sarria EE, Mattiello R, Yao W, Chakr V, Tiller CJ, Kisling J, Tabbey R, Yu Z, Kaplan MH, Tepper RS. Atopy, cytokine production, and airway reactivity as predictors of pre-school asthma and airway responsiveness. Pediatr Pulmonol 2014;49(2):132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Filion KB, Abenhaim HA, Mottillo S, Joseph L, Gervais A, O’Loughlin J, Paradis G, Pihl R, Pilote L, Rinfret S, Tremblay M, Eisenberg MJ. The effect of smoking cessation counselling in pregnant women: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BJOG 2011;118(12):1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Schneider S, Huy C, Schutz J, Diehl K. Smoking cessation during pregnancy: a systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Rev 2010;29(1):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Yieh L, McEvoy CT, Hoffman SW, Caughey AB, MacDonald KD, Dukhovny D. Cost effectiveness of vitamin c supplementation for pregnant smokers to improve offspring lung function at birth and reduce childhood wheeze/asthma. J Perinatol 2018;38(7):820–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.