Abstract

Since noninvasive central blood pressure (BP) measuring devices are readily available, central BP has gained growing attention regarding its clinical application in the management of hypertension. The disagreement between central and peripheral BP has long been recognized. Some previous studies showed that noninvasive central BP may be better than the conventional brachial BP in association with target organ damages and long‐term cardiovascular outcomes. Recent studies further suggest that the central BP strategy for confirming a diagnosis of hypertension may be more cost‐effective than the conventional strategy, and guidance of hypertension management with central BP may result in less use of medications to achieve BP control. Despite the use of central BP being promising, more randomized controlled studies comparing central BP‐guided therapeutic strategies with conventional care for cardiovascular events reduction are required because noninvasive central and brachial BP measures are conveniently available. In this brief review, the rationale supporting the utility of central BP in clinical practice and relating challenges are summarized.

Keywords: brachial BP, central BP, diagnosis, high BP, hypertension, management, peripheral BP

1. INTRODUCTION

To maintain the circulation of blood flow, the ejection of the stroke volume into the central aorta requires the pressure generated by left ventricle to overcome the pulsatile and resistive loads of the entire arterial tree.1 As the pressure wave (PW) propagating along the arterial bed, it increases in the whole amplitude of the pulse pressure (PP) as it travels distally, that is, a “gradual widening” of the PP between two sites of the arterial bed. The increased amplitude of arterial pulse along the elastic and conduit arteries is quantified as the blood pressure (BP) amplification; that is, systolic BP (SBP) and PP are higher at peripheral arteries than that in the central aorta. Mean BP and diastolic BP remain almost unchanged (or slightly decreases because of viscous dissipation) between the two sites.2 Although brachial BP has been routinely measured in daily practice, many studies have been conducted to address the prognostic and therapeutic impact of this noticeable discrepancy between brachial BP and central BP. Central BP, the pressure measured from the central aorta or common carotid arteries,1 is determined by the interaction between function of left ventricle, large arteries and arterioles, and structure of aortic root, arterial bifurcations and arterial narrowing, and may therefore directly and better reflect the impact of pulsatile load.3

Central BP has gained growing attention concerning its clinical application in the management of hypertension since noninvasive central BP measuring devices are readily available. After the introduction of cuff‐based techniques developed to obtain noninvasive central BP,4, 5, 6 its convenient measurement can realize the use of central BP concept in daily clinical practice. Moreover, the Artery Society task force, in response to the burgeoning noninvasive central BP monitoring devices, has proposed a validation standard.7 One of the major suggestions in the consensus statement is the further classification of central BP monitoring devices based on its purpose. It suggests to classify the devices into two types: Type I devices estimate central BP relative to the measured brachial BP, and type II devices estimate the intra‐arterial central BP.7 The features are a relatively accurate pressure difference between central and peripheral sites for type I devices and a relatively accurate absolute central BP value for type II devices.

BP measurements are conventionally obtained at the brachial arteries. Although brachial BP readings highly correlate with central BP and are the gold standard for the diagnosis and management of hypertension, substantial individual discrepancies between central and peripheral BP exist. Such discrepancies have long been a popular research topic, and whether central BP is a better clinical indicator than brachial BP has also been debated vehemently.8, 9 In this review, we will address briefly the rationale supporting the clinical use of central BP monitoring.10

2. METHODS AND DEVICES USED FOR NONINVASIVE ESTIMATION OF CENTRAL BP

Pressure waveform of carotid artery is a good surrogate for central aortic pressure waveform.11, 12, 13 However, the commonly used methodology utilizes waveforms obtained from peripheral arteries for noninvasive central BP estimation with either tonometry‐based11, 14, 15, 16 or cuff‐based techniques.4, 5, 6 The common working principles of these central BP estimations include transfer function, pulse waveform analysis, and N‐point moving average (NPMA). Transfer function is a mathematical relationship between two physical properties. The details of the measurement concept and procedures can be found in research performed with a commercial apparatus.17, 18 It has been the most popular central BP measurement device to date. Pulse waveform analysis can be used to identify waveform characteristics. It has been shown that peak of SBP2, the late systolic should of a pressure waveform resulting from distal PW reflections agrees well with the peak of central aortic pressure waveforms (central SBP).19, 20 Besides, using comprehensive waveform analysis including SBP2 and corresponding regression equations, central SBP and PP can be accurately estimated.4, 21 Recently, it has been demonstrated that one can use NPMA method to estimate central aortic SBP (SBP‐C).16 NPMA is a mathematical low‐pass filter that is frequently used in the engineering field for removing random noise from a time series by using a common denominator related to the sampling frequency. The high‐frequency components, which cause substantial transformations from central to peripheral aortic pressure waveforms resulting primarily from arterial wave reflections,22 can be eliminated by the application of the NPMA.16, 23 Table 1 summarizes current available devices for measuring central BP.

Table 1.

Summary of devices capable of measuring central blood pressure

| Device company | Site of record | Method of waveform recording (sensor) | Method of estimation calibration | Calibration | Invasive validation/FDA approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office central BP monitoring | |||||

| PulsePen DiaTecne srl., Italy | Carotid artery | Applanation tonometry Single, manual | Simple substitution | Brachial cuff MAP/DBP | Yes/No |

| Complior Alam Medical, France | Carotid artery | Applanation tonometry, Single, fixed | Simple substitution | Brachial cuff MAP/DBP | Yes/No |

| NIHem Cardiovascular Engineering Inc, USA | Carotid artery | Applanation tonometry, Single, manual | Simple substitution | Brachial cuff MAP/DBP | Yes/No |

| HEM‐9000AI Omron Healthcare, Japan | Radial artery | Applanation tonometry Arrayed, fixed | SBP2 + regression | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/No |

| GaonHanbyul Meditech, Korea | Radial artery | Applanation tonometry Single, fixed | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| SphygmoCorCVMS, AtCor Medical, Australia | Radial artery | Applanation tonometry Single, manual | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| SphygmoCor XCELAtCor Medical, Australia | Brachial artery | Subdiastolic brachial cuff plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| Oscar 2 with SphygmoCor SunTech Medical, USABrachial | Brachial artery | Subdiastolic brachial cuff plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| cBP301Centron Diagnostics, UK (acquired bySunTech Medical) | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| Mobil‐O‐GraphI.EM GmbH, GermanyBrachialartery | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| ArteriographTensioMed Ltd., Hungary | Brachial artery | Supra‐systolic brachial cuff plethysmography | SBP2 + regression | Brachial cuff MAP/DBP | Yes/No |

| Vicorder Skidmore Medical Ltd., UK | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff MAP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| BPLab Petr Telegin, Russia | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| BP + Uscom Ltd., Australia (acquire Pulsecor Ltd., Cardioscope II) | Brachial artery | Supra‐systolic brachial cuff plethysmography | Physical model Brachial supra‐systolic waveform | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/No |

| DynaPulse Pulse Metric Inc, USA | Brachial artery | Supra‐systolic brachial cuff plethysmography | Physical model | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| WatchBP Microlife Corp, Taiwan | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | (SBP2, DBP, As, Ad) + regression | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| ARCsolver + VaSeraVS‐1500Austrian Institute of Technology, Austria | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| Ambulatory Central BP Monitors | |||||

| BPro + A‐Pulse, HealthSTATS, Singapore (acquired by Hillrom) | Radial artery | Applanation tonometry Single, fixed (watch type) | N‐point moving average | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| Mobil‐O‐Graph NGI.EM GmbH, Germany | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| Arteriograph 24 h, TensioMED Ltd., Hungary | Brachial artery | Supra‐systolic brachial cuff plethysmography | SBP2 + regression | Brachial cuff MAP/DBP | Yes/No |

| ABPM 7100Welch Allyn, Inc (acquired by Hillrom) | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | No/No |

| WatchBP O3 (2G), Microlife AG, Widnau, Switzerland | Brachial artery | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | (SBP2, DBP, As, Ad) + regression | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

| Oscar 2 with SphygmoCor, SunTech Medical | Brachial artery | Subdiastolic brachial cuff plethysmography | GTF | Brachial cuff SBP/DBP | Yes/Yes |

Abbreviations: Ad, area under pressure wave curve during diastole; As, area under PW curve during systole; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GTF, generalized transfer function; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SBP2, second peak of radial or brachial PW.

It is suggested that the accuracy of central BP should be examined against the invasive measurements counterparts.7 Accuracy of current central BP methods and devices has been investigated in several systematic review.24, 25, 26 It seems that the accuracy is device specific,27 and the major limitation is the accuracy of cuff BP used for waveform calibration.24, 28

3. UTILITY OF CENTRAL BP MONITORING IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

3.1. Peripherally obtained BP does not accurately reflect central pressure because of pressure amplification

As shown in a previous study, a large proportion of subjects with high‐normal brachial SBP had comparable central SBP as those with stage 1 hypertension.29 This discrepancy was also noted for subjects with normal brachial BP, many of whose central BPs were in the same category as those with stage 1 hypertension. If central BP is a better target for therapy, the misclassification by brachial BP may lead to over‐ or under‐treatment of hypertension and may be clinically relevant.30 The diagnosis of hypertension, according to either office, home, or ambulatory BP measurements, is currently based on recordings from the brachial arteries. Because of the phenomenon of PP amplification, brachial SBP and PP are usually higher than the corresponding readings in the central aorta.2, 15, 31, 32, 33 However, either by the auscultatory method or automatic oscillometric sphygmomanometers, the noninvasively measured brachial SBP and PP, are usually lower than the invasively measured intra‐arterial readings.34 As a consequence, noninvasive brachial SBP readings may approach to values of central SBP35; therefore, it might be reasonable to use noninvasive brachial SBP as an estimate of central SBP. Nonetheless, robust evidence suggests that there are substantial disagreements of central BP among individuals with similar brachial BP.36, 37 Moreover, although the averaged invasive central SBP is similar to averaged brachial cuff SBP, there is substantial variability, that is, under and over estimation of central SBP by the cuff SBP, which refutes brachial cuff SBP being an accurate representation of central SBP.26, 37, 38 The PP amplification, the disagreement between central and peripheral BP varies within‐ and between‐individuals.39 More importantly, such variability depends on a number of factors, including age, sex, body height, heart rate, medications, and systemic vascular diseases.36, 40, 41 Besides, noninvasive brachial SBP as a surrogate for central SBP has been shown to have a large random error.37

3.2. Central aortic pressure is a better predictor of cardiovascular outcome than peripheral pressure

Central BP may reflect the pulsatile load on the heart and large arteries better than brachial BP, particularly in individuals with a prominent PP amplification.3 It has been demonstrated that central SBP was more closely associated with left ventricular mass index, carotid intima‐media thickness, and pulse wave velocity, compared with brachial SBP,42, 43 whereas brachial SBP might be superior to central SBP in identifying albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes.44 In addition, longitudinal studies further support that the changes of central BP rather than brachial BP related to the regression of left ventricular mass index and carotid intima‐media thickness,45, 46 and microalbuminuria and cognitive aging.43, 47

In a systematic review of 85 studies, central compared with brachial BP seems to be more strongly associated with most of the investigated indices of preclinical organ damage.42 With regard to the relationship between central BP and cardiovascular outcomes, we previously showed that central SBP and PP were more predictive of cardiovascular mortality than brachial SBP and PP in a Taiwanese cohort.48 In addition, central SBP and PP were significantly associated with cardiovascular events, as well as brachial measurements, in a meta‐analysis of 11 studies with 5648 subjects,49 while the superiority of central over brachial measurements was marginal (nonsignificant) for central PP and nonapparent for central SBP. The cohort studies investigating the prognostic role of central BP have been summarized in Table 2. Recently, the clinical benefits of different antihypertensive agents observed in the ASCOT study were more associated with the reduction of central rather than brachial BP,17 which ignited the application of central BP for clinical practice.50 If precision of central BP measurement could be improved, as for some type II central BP devices, we may see more substantial prognostic difference.

Table 2.

Overview of studies on the association between central pressures and augmentation index and clinical endpoints sorted by date of publication

| Study | Population‐sample size | Age (y) | Men (%) | Follow‐up duration | Events | Index | Modality | Attrition bias (loss/events ratio) | Index modeled | Adjusted for |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lu et al70 | Stable CAD/angioplasty (n = 87) | 72.5 ± 5.1 | 92 | 6.1 ± 4.1 m | 39 cases of restenosis | Aortic PP; Aortic PP/MAP; Aortic PP/DBP | Invasive (fluid‐filled system, 7F pig‐tail catheter) | Not reported | Continuous; optimal cut‐off by ROC curve | Risk factors for restenosis (not specified) |

| London et al71 | ESRD (n = 180) | 54 ± 16 | 60 | 52 ± 36 m | 70 deaths; 40 CV deaths | Carotid AIx | Tonometry of CCA | 0% | Continuous; quartiles; optimal cut‐off by ROC curve | Age, sex, DBP, HR, smoking, duration of dialysis, blood chemistry analyses, ACEI prescription, PWV |

| Safar et al72 | ESRD (n = 180) | 54 ± 16 | 60 | 52 ± 36 m | 70 deaths; 40 CV deaths | Carotid SBP, PP, brachial‐carotid PP amplification | Tonometry of CCA | 0% | Continuous; quartiles; optimal cut‐off by ROC curve | Age, sex, DBP, HR, smoking, duration of dialysis, blood chemistry analyses, ACEI prescription, PWV |

| Ueda et al73 | CAD/angioplasty (n = 103) | 62 ± 9 78 | 78 | 6 m | 36 cases of restenosis | Aortic AIx; aortic inflection time | Invasive (fluid‐filled system, 5F pig‐tail catheter) | 0% | Continuous; tertiles | Age, sex, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, stent size, HR, inflection time |

| Chirinos et al74 | CAD or nonobstructive coronary atherosclerosis (n = 297) | 63.8 ± 10.3 | 100 | 40 ± 14 m | 58 deaths; 128 CV events | Aortic PP, AP, AIx | Invasive (low‐compliance fluid‐filled system) | 11% | Continuous | Age, diastolic or MAP, diabetes, smoking, HR, height, use of drugs, lipid levels, ejection fraction, C‐reactive protein, extent of CAD |

| Weber et al75 | CAD/angioplasty (n = 262) | 65 ± 10 | 71 | 24 m | 12 deaths; 61 CV events | HR‐corrected aortic AIx | Tonometry of radial artery, GTF | 1.60% | Continuous; tertiles | Age, sex, smoking, prior MI or stroke, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, extent of CAD, medications, triglycerides, creatinine clearance, BMI, SBP, or PP |

| Dart et al76 | Elderly female hypertensives (n = 484) | 72 ± 5 | 0 | 49 m (median) | 53 CV events | Carotid SBP, PP; AIx | Tonometry of CCA | Not reported | Dichotomous | Age, cholesterol, smoking |

| Covic et al77 | ESRD (n = 92) | 42.6 ± 11.2 | 54 | 61 ± 25 m | 15 deaths | HR‐corrected aortic AIx | Tonometry of radial artery, GTF | Not reported | Tertiles | Age, sex, time on dialysis, SBP, PP, LVMI, use of ACE inhibitors |

| Roman et al18 | American Indians free of CVD (n = 2403) | 63.5 ± 7.5 | 35 | 58 ± 16 m | 386 deaths; 67 CV deaths; 319 CV events | Aortic SBP, PP | Tonometry of RA—transfer function | 0.80% | Continuous | Age, sex, current smoking, BMI, total/HDL ratio, creatinine, fibrinogen, diabetes, HR |

| Jankowski et al78 | Subjects undergoing nonemergency coronary angiography (n = 1109) | 52.7 ± 19.2 | 74 | 52.7 ± 19.2 m | 90 deaths; 71 CV deaths; 246 CV events | Aortic PP; PPf | Invasive (low‐compliance fluid‐filled system) | 15% | Continuous; quartiles | Age, sex, ejection fraction, mean coronary artery stenosis, heart failure, HR, risk factors, CVD, eGFR, drugs |

| Pini et al 2E + 07 | Community‐dwelling individuals 65 y (n = 398) | 73 ± 6 | 45 | 94 ± 24 m | 106 deaths; 45 CV deaths; 122 CV events | Aortic SBP, PP, AIx | Tonometry of CCA | Not reported | Continuous | Age, sex |

| Wang et al48 | normotensive and untreated hypertensive (n = 1272) | M: 52.4 ± 12.9 F: 52.0 ± 12.7 | 53 | 10 y | 130 died, 37 CV deaths | central and brachial SBP and PP | sequential nondirectional Doppler (Parks model 802; Parks Medical Electronics, Aloha, Oregon, USA) | Not reported | Continuous | Age, sex, heart rate, BMI, current smoking, fasting plasma glucose levels, cholesterol/HDL ratio, PWV, LVM, IMT, and eGFR |

| Chirinos. et al79 | White, African American, Hispanic, or Chinese and who were free of clinically apparent CV disease (n = 5960) | 62 (53‐70) | 48 | 7.61 y | 407 first CVE 281 first hard CVE 117 first episode of CHF | Reflection magnitude AIx PP amplification | tonometry device–GTF noninvasively | 5% | Continuous |

Adjusted model 1 age, gender, total cholesterol, HDL‐cholesterol, smoking, SBP, DBP, diabetes mellitus Adjusted model 2 further adjusts for ethnicity, body height, body weight, antihypertensive medication use, HR, and eGFR |

| Wassertheurer et al80 | patients with CKD stages 2‐4 (n = 159) | 59.9 ± 15.2 | 55 | 42 mo (range 30‐50 mo | 13 patients died nine CV deaths | brachial SBP aortic SBP | oscillometric method (Mobil‐OGraph PWA monitor; IEM, Stolberg, Delaware, USA) | Not reported | Continuous | Age, sex, and anthropometric measures |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; AIx, augmentation index; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCA, common carotid artery; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CV, cardiovascular; CVE, cardiovascular event; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; GTF, generalized transfer function; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HR, heart rate; IMT, intima‐media thickness; LVM, left ventricular mass; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MI, myocardial infarction; PI, pulsatility index (pulse pressure/DBP); PP, pulse pressure; PPf, fractional pulse pressure (pulse pressure/mean pressure); PWV, pulse wave velocity; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; SBP, systolic blood pressure

3.3. Antihypertensive medications have differential effects on central pressures despite similar reductions in brachial BP

It has long been recognized that individual discrepancies between central and peripheral BP may be magnified during hemodynamic changes or after pharmacological interventions.24 The differential responses of central BP vs brachial BP to various antihypertensive agents are highly variable among individuals in clinical studies.51, 52 It has been suggested that angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, as well as nitrates, may have a more beneficial effect on central BP than beta‐blockers, despite their similar effects on brachial BP.53, 54 Randomized controlled trials investigating the differential response between central and peripheral BP to different classes of pharmacological interventions have been summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Randomized controlled trials investigating the differential response of central vs brachial blood pressure to antihypertensive agents

| Study | Drug class or placebo studied | Sample size | Type of study | Site of artery | Design | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guerin 199281 | BB vs CCB | 20 | Drug comparison | Carotid | Parallel | |

| London 199482 | CCB vs ACEI | 24 | Drug | Carotid | Parallel | End‐stage renal disease |

| Chen 199583 | ACEI vs BB | 79 | Drug comparison | Carotid | Parallel | cSBP not reported |

| Mahmud 200084 | ARB | 18 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | |

| Asmar 2001b85 | Placebo vs ARB | 27 | Placebo controlled, drug comparison | Radial | Crossover | Hypertension + Diabetes |

| Asmar 2001a86 | ACEI + D vs BB | 471 | Drug comparison, combination | Carotid | Parallel | |

| Mitchell 200287 | ACEI vs omapatrilat | 167 | Drug comparison | Carotid | Parallel | |

| Deary 200288 | Placebo vs ACEI vs CCB vs ACEI vs BB vs AB vs D | 30 | Placebo controlled, drug comparison | Radial | Crossover | Separate data for sexes |

| de Luca 200489 | ACEI + D vs BB | 146 | Drug comparisons | Radial | Parallel | Essential hypertension |

| Neal 200490 | CCB vs ACEI vs BB | 24 | Drug comparison | Radial | Crossover | Liver transplantation |

| London 200491 | ACEI + D vs BB | 181 | Drug comparison, combination | Carotid | Parallel | |

| Morgan 200492 | Placebo vs CCB vs ACEI vs BB vs D; | 321 | Placebo controlled, drug comparison | Radial | Crossover | |

| Mahmud 200593 | D vs spironolactone | 24 | Drug comparison | Radial | Crossover | |

| Dart 200794 | ACEI vs D | 479 | Drug comparison | Carotid | Parallel | |

| Jiang 200795 | ACEI vs D | 101 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | |

| Williams 200617 | BB + D vs ACEI + CCB | 2199 | Combination | Radial | Parallel | |

| Dhakam 200696 | BB vs ARB | 21 | Drug comparison | Radial | Crossover | |

| Schneider 200897 | ARB vs BB | 156 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | |

| Dhakam 200898 | Placebo vs BB vs nebivolol | 16 | Placebo controlled, drug comparison | Radial | Crossover | |

| Mahmud 200899 | BB vs nebivolol | 40 | Drug comparison | Radial | parallel | |

| Matsui 200958 | ARB + CCB vs ARB + D | 207 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | |

| Mackenzie 2009100 | CCB vs ACEI vs BB vs D | 59 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | Isolated systolic hypertension |

| Boutouyrie 2010101 | ARB + CCB vs ARB + BB | 393 | Combination | Radial | Parallel | |

| Dol 2010102 | CCB vs D | 37 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | |

| Kaufman 2010103 | losartan 100 mg, isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN) 60 mg, losartan 100 mg + ISMN 15 mg, losartan 100 mg + ISMN 60 mg, and placebo | 13 | Double‐blind, crossover study | Radial | Crossover | Essential hypertension |

| Cockburn 2010104 | propranolol 80 mg vs bisoprolol 20 mg vs placebo | 20 | Double‐blind, crossover study | Finger | Crossover | |

| Manisty 2010105 | amlodipine with perindopril vs atenolol with bendroflumethiazide‐K | 259 | Prospective, randomised, open‐label, blinded endpoint parallel group | Carotid | Parallel | Essential hypertension |

| Ferdinand 201151 | Aliskiren + D vs CCB | 53 | Drug comparison, combination | Carotid | Parallel | African American |

| Takenaka 2012106 | benidipine vs amlodipine | 67 | Open‐label, parallel group, randomized, controlled study | Radial | Parallel | Chronic kidney disease |

| Virdis 2012107 | aliskiren (150‐300 mg/daily) or ramipril (5‐10 mg/daily) | 50 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | Essential hypertension |

| Izzo 2012108 | carvedilol vs valsartan | 30 | Forced‐titration, random order‐entry crossover study | Radial | Crossover | Essential hypertension |

| Vitale 2012109 | BB + D vs ARB + D | 65 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | Essential hypertension |

| Takami 2012110 | Azelnidipine (16 mg daily) + D vs amlodipine (5 mg daily) (25 patients/group) + D | 50 | Prospective, randomized, open‐label parallel group | Radial | Parallel | Essential hypertension |

| Ruilope 2013111 | ARB + CCB vs ACEI + CCB | 486 | Parallel group, noninferiority study, | Radial | Parallel | Hypertensive subjects |

| Fogari 2013112 | imidapril vs ramipril (R) | 176 | Prospective, randomised, open‐label, blinded endpoint parallel group | Radial | Parallel | Diabetic hypertensive patients with microalbuminuria |

| Koumaras 2013113 | quinapril vs aliskiren vs atenolol vs nebivolol | 72 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | Treatment‐naive, adult patients with uncomplicated, stage I‐II, essential hypertension |

| Eeftinck Schattenkerk 2013114 | nebivolol/hydrochlorothiazide vs metoprolol/hydrochlorothiazide | 22 | Randomized, double‐blind | Radial | crossover | Aged 40‐70 y, with untreated stage 2 hypertension |

| Radchenko 2013115 | ARB + D vs BB + D | 59 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | Moderate‐to‐severe hypertension |

| Ihm 2013116 | CCB vs ARB | 200 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | Mild to moderate essential hypertensives. |

| Agnoletti 2013117 | amlodipine 5mg, or candesartan 8mg, or indapamide sustained‐release 1.5mg, in comparison with placebo. | 145 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | BP ≥ 150 to < 180 mm Hg and DBP of ≥ 95 to < 110≥160 to < 180 mm Hg and DBP of < 90 mm Hg |

| Takami 2013118 | Azelnidipine plus olmesartan vs amlodipine plus olmesartan | 52 | Prospective, randomized, open‐label parallel group study | Radial | Parallel | Patients with SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg |

| Hare 2013119 | spironolactone 25mg daily (n = 58) or placebo (n = 57) | 115 | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled | Radial | Parallel | Hypertensive response to exercise |

| Park 2013120 | Bisoprolol vs Atenolol | 209 | Prospective, randomized, open‐label, active‐controlled trial | Radial | Parallel | |

| Dorresteijn 2013121 | aliskiren 300 mg vs sympathoinhibition (using moxonidine 0.4 mg) vs D (using hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg) vs placebo | 31 | Four‐way, double‐blind, single‐center, crossover study | Radial | Crossover | Obesity‐related hypertension |

| Matthesen 2013122 | placebo vs amiloride vs spironolactone | 23 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | Essential hypertension |

| Parati 2013123 | acetazolamide 250 mg b.i.d. or placebo | 42 | Drug comparison | Radial | Parallel | Healthy lowlanders without known cardiovascular disease |

| Park 2014124 | ARB + CCB vs maximal ARB vs Maximal CCB | 391 | Open‐label, randomized, active‐controlled | Radial | Parallel | Aged 20‐70 y with grade 2 or grade 3 hypertension |

| Dillinger 2015125 | Ivabradine vs Placebo | 12 | Randomized, double‐blind | Radial | Crossover | Normotensive subjects with CAD |

| Bruno 2015126 | ACEI + CCB vs ACEI + Diuretics | 76 | Randomized, open labeled | Radial | Parallel | Hypertensive subjects with metabolic syndrome |

| Metoki 2015127 | Maximal ARB vs ARB + Diuretics | 200 | Drug comparison, combination | Radial | Parallel | Essential hypertension aged from 20 to 80 y |

| Redon 2016128 | ACEI + CCB vs ARB + CCB | 88 | Noninferiority, randomized, double‐blind, double‐dummy parallel group, controlled design trial, | Radial | Parallel | After Missed Dose in Type 2 Diabetes. |

| Rimoldi 2016129 | Ivabradine vs Placebo | 46 | Single‐blinded fashion | Invasive central BP | Parallel | Chronic stable coronary artery disease |

| Rosenbaek 2017130 | Placebo or diluted NaNO2 in three different doses | 12 | Placebo controlled, dose‐response | Radial | Crossover | Healthy volunteer |

| Suojanen 2017131 | Placebo vs BB | 16 | Double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial | Radial | Crossover | never‐treated 16 Caucasian males with grade I‐II primary hypertension |

| Schreglmann 2017132 | Pyridostigmine bromide vs fludrocortisone | 13 | Double‐blind, randomized, active‐control, crossover, | Radial | Crossover | Parkinson's disease with orthostatic hypotension |

| Fraig 2018133 | fixed‐dose combination of amlodipine 10 mg/valsartan 160 mg vs nebivolol 5 mg/valsartan 160 mg | 137 | Drug comparison, combination | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | Parallel | Grade 2 or more hypertensive patients |

| Rosenbaek 2018134 | Placebo, allopurinol 150 mg twice daily (TD), enalapril 5 mg TD, or acetazolamide 250 mg TD | 16 | Placebo controlled, drug comparison, | Radial | Crossover | Healthy volunteer |

| Georgianou 2019135 | nebivolol (5 mg/d), olmesartan (20 mg/d), or no‐treatment | 60 | Single‐blinded fashion | Brachial cuff pulse volume plethysmography | Parallel | Acute phase of ischemic stroke |

Abbreviations: AB, alpha‐blocker; ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker, BB, beta‐blockers, CCB, calcium channel blocker; D, diuretics.

Similarly, various classes of antihypertensive drugs may exert different effects on the PP amplification. Compared with diuretics and beta‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, dihydropyridine calcium blockers, and nitrates may exert a favorable effect on the PP amplification.3, 30, 55, 56 The observed less beneficial effect of beta‐blockers (mainly atenolol) on cardiovascular outcomes57 could be explained by the unfavorable effect on the PP amplification.17, 53 These speculations were supported by the CAFE substudy of the ASCOT trial,17 and the J‐Core study.58

Although we have previously proposed the central BP threshold of 130/90 mm Hg for the diagnosis of hypertension,33 the treatment targets in patients with elevated central BP have yet to be defined. Previous studies have shown that guidance of hypertension management with central BP may result in less use of medications to achieve BP control without adverse effects.30 A recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated that maximization of goal‐directed medical therapy in heart failure patients could be more achieved by using central BP, as compared with conventional office brachial BP, during additional medicine titration, which subsequently enhanced afterload reduction and lead to reverse remodeling without increased risk of hypotension or worsening renal function.59

In uncomplicated hypertensive subjects with low to medium risk, it is reasonable to lower central BP to <130/90 mm Hg. However, outcome‐driven central BP‐guided treatment target studies should be conducted for other specific compelling disease status.

3.4. Isolated central hypertension and isolated brachial hypertension are associated with increased cardiovascular risks

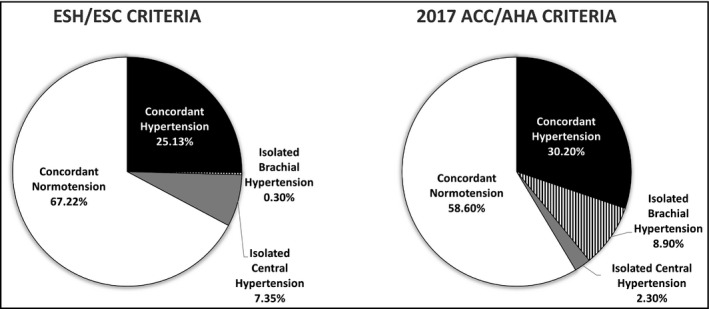

The discrepancy between central and brachial BP could be used to define phenotypes of hypertension.60, 61 Based on the ESH/ESC hypertension guidelines for brachial hypertension (brachial SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg or brachial DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg or using antihypertensive medicine) and central hypertension criteria33 (≥130 mm Hg for central SBP or ≥ 90 mm Hg for central DBP or using antihypertensive medicine), in a national representative cohort, phenotypes of isolated central and isolated brachial hypertension among adults have been identified (Figure 1).62 Subjects with isolated central hypertension had a significantly higher estimated 10‐year coronary heart disease risk than those without central or brachial hypertension.62 In the Northern Shanghai study, elderly Chinese subjects with isolated central hypertension had higher levels of left ventricular mass index, carotid‐formal pulse wave velocity, and urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio than those without central or brachial hypertension.63 Moreover, based on the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension threshold, a higher proportion of subjects with isolated brachial hypertension thresholds (130/80 mm Hg) has been identified (Figure 1).64 Subjects with isolated brachial hypertension had an increased risk of coronary heart disease similar to those with isolated central hypertension and were characterized by young age, male sex, and a high prevalence of isolated diastolic hypertension, implying minimal evidence of the presence of arterial stiffness or vascular aging.64

Figure 1.

The national weighted proportion of concordant hypertension, concordant normotension, isolated brachial hypertension, and isolated central hypertension, according to the criteria of brachial hypertension with ESH/ESC (140/90 mm Hg) and 2017 ACC/AHA (130/80 mm Hg) thresholds. Central hypertension was defined by central blood pressure ≥130/90 mm Hg or using antihypertensive medicine

4. FUTURE PERSPECTIVES ON THE USE OF CENTRAL BP TO MANAGE HYPERTENSION

We have evidently shown in a previous systematic review that current central BP estimating methods are theoretically suitable.24 However, the major errors of these central BP measurement techniques result from the inaccurate noninvasive BP used to calibrate the peripheral waveforms. In a recently published systematic review, cuff BP has variable accuracy for measuring either brachial or aortic intra‐arterial BP, which adversely influences correct BP classification26 and inevitably makes waveform calibration inadequate. Therefore, the measurement accuracy of both noninvasive brachial and central BP still has room for improvement.26, 65 Recently, World Hypertension League, International Society of Hypertension, and other supporting hypertension organizations have together issued a position statement to call for regulating manufacture and marketing of BP devices and cuffs.66 With the joint efforts, validated automatic BP devices are more readily available and more accurate noninvasive brachial and central BP measurements could be rendered in the care of cardiovascular patients.

Despite that central BP may be better than brachial BP in predicting cardiovascular outcomes,5, 20, 22 it is arguable that the inconsistent superiority of central BP over brachial BP may reflect a true pathophysiological issue or is potentially biased by methodological weakness.67, 68 It should be acknowledged that most outcome studies were conducted in the elderly in whom brachial and central pressures are similar, and no outcome studies have been conducted in younger patients, in whom a much greater difference between brachial and central pressures is expected. Convincing evidence has shown that different antihypertensive treatments can differentially reduce central vs brachial BP; however, studies investigating whether such therapeutic difference could be translated into clinical outcomes are required. Future prospective studies are needed to demonstrate the superiority of the central BP‐guided strategy over conventional brachial BP strategy in hypertension screening in the community or management at clinical practice.69 Even central BP may have superior advantages over conventional office BP, its current utility is still mainly restricted in research field. Using central BP in the assessment of cardiovascular health, such as predicting one's cardiovascular risk or diagnosing whether he or she has hypertension can be implemented soon if more convincing evidence can be accumulated. However, using central BP to guide clinical practice is a more difficult case given that even home BP or ambulatory BP are not often used as a therapeutic guidance tool. The management of hypertension is largely based on BP obtained from conventional office BP over decades. More randomized controlled trials demonstrating that controlling both brachial and central hypertension can bring benefits to patients may be the first step of the application of central BP in routine clinical practice. Other barriers from knowledge, attitudes, and external factors such as guideline and reimbursement issue should be dealt with to facilitate the translational process afterward. Longitudinal follow‐up studies are also required to prove that isolated brachial hypertension and isolated central hypertension, the two new hypertension phenotypes identified by the simultaneously obtained noninvasive central and brachial BP measures, indeed carry increased cardiovascular risks and deserve respective management.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In this brief review, we summarized the rationale supporting the clinical utility of central BP since it can be conveniently measured noninvasively. Noninvasive central BP is likely better than the conventional brachial BP in association with target organ damages and long‐term cardiovascular outcomes, but more evidence is required to support the use of central BP in diagnosing hypertension and monitoring the management of hypertension with central BP in routine clinical practice.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

K Kario received research grants from Omron Healthcare, A&D, and Fukuda Denshi Co. Ltd. S Park has received research grants and honoraria from Pfizer. S Siddique has received honoraria from Bayer, Novartis, Pfizer, ICI, and Servier; and travel, accommodation, and conference registration support from Atco Pharmaceutical, Highnoon Laboratories, Horizon Pharma, ICI, Pfizer, and CCL. YC Chia has received honoraria and sponsorship to attend conferences and CME seminars from Abbott, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Orient Europharma, Pfizer, and Sanofi; and a research grant from Pfizer. J Shin has received honoraria and sponsorship to attend seminars from Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda, Menarini, MSD, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Sanofi. CH Chen has served as an advisor or consultant for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; has served as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for AstraZeneca; Pfizer Inc; Bayer AG; Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Daiichi Sankyo, Inc; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; SERVIER; Merck & Co., Inc; Sanofi; TAKEDA Pharmaceuticals International; and has received grants for clinical research from Microlife Co., Ltd. R Divinagracia has received honoraria as a member of speaker's bureaus for Bayer, Novartis, and Pfizer. J Sison has received honoraria from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis. GP Sogunuru has received a research grant related to hypertension monitoring and treatment from Pfizer. JC Tay has received advisory board and consultant honoraria from Pfizer. BW TEO has received honoraria for lectures and consulting fees from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Servier, MSD, and Novartis. JG Wang has received research grants from Bayer, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Phillips; and lecture and consulting fees from Bayer, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Servier, and Takeda. Y Zhang has received research grants from Bayer, Novartis, and Shuanghe; and lecture fees from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Servier, and Takeda. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Scott Solomon, John McMurray, Milton Packer, Jean Rouleau, Michael Zile, Marc Hao‐Hao‐Min Cheng, Shao‐Yuan Chuang contributed to the first draft of the article. Tzung‐Dau Wang, Kazuomi Kario, PeeraBuranakitjaroen, Yook‐Chin Chia, Romeo Divinagracia, Satoshi Hoshide, Huynh Van Minh, Jennifer Nailes, Sungha Park, Jinho Shin, Saulat Siddique, Jorge Sison, Arieska Ann Soenarta, Guru Prasad Sogunuru, ApichardSukonthasarn, Jam Chin Tay, Boon Wee Teo, YudaTurana, Narsingh Verma, Yuqing Zhang, Ji‐Guang Wang, and Chen‐Huan Chen critically reviewed each draft and provided substantial input on the content.

Cheng H‐M, Chuang S‐Y, Wang T‐D, et al. Central blood pressure for the management of hypertension: Is it a practical clinical tool in current practice?. J Clin Hypertens. 2020;22:391–406. 10.1111/jch.13758

REFERENCES

- 1. Nichols WW, O'Rourke MF, Vlachopoulos C. McDonald's Blood Flow in Arteries: Theoretic, Experimental and Clinical Principles, 6th edn. London: Arnold; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Avolio AP, Van Bortel LM, Boutouyrie P, et al. Role of pulse pressure amplification in arterial hypertension. Experts' opinion and review of the data. Hypertension. 2009;54(2):375‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng H‐M, Park S, Huang Q, et al. Vascular aging and hypertension: implications for the clinical application of central blood pressure. Int J Cardiol. 2017;230:209‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheng H‐M, Wang K‐L, Chen Y‐H, et al. Estimation of central systolic blood pressure using an oscillometric blood pressure monitor. Hypertens Res. 2010;33(6):592‐599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weber T, Wassertheurer S, Rammer M, et al. Validation of a brachial cuff‐based method for estimating central systolic blood pressure. Hypertension. 2011;58(5):825‐832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Millasseau SC, Guigui FG, Kelly RP, et al. Noninvasive assessment of the digital volume pulse. Comparison with the peripheral pressure pulse. Hypertension. 2000;36(6):952‐956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sharman JE, Avolio AP, Baulmann J, et al. Validation of non‐invasive central blood pressure devices: ARTERY Society task force consensus statement on protocol standardization. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(37):2805‐2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sharman J. Central pressure should be used in clinical practice. Artery Res. 2014;8(4):121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitchell GF. Central pressure should not be used in clinical practice. Artery Res. 2015;9:8‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu D‐Y, You L‐K, Sung S‐H, et al. Abnormal pulsatile hemodynamics in hypertensive patients with normalized 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure by combination therapy of three or more antihypertensive agents. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(4):281‐289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benetos A, Tsoucaris‐Kupfer D, Favereau X, Corcos T, Safar M. Carotid artery tonometry: an accurate non‐invasive method for central aortic pulse pressure evaluation. J Hypertens. 1991;9(Suppl. 6):S144‐S145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen C‐H, Ting C‐T, Nussbacher A, et al. Validation of carotid artery tonometry as a means of estimating augmentation index of ascending aortic pressure. Hypertension. 1996;27(2):168‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Segers P, Rietzschel E, Heireman S, et al. Carotid tonometry versus synthesized aorta pressure waves for the estimation of central systolic blood pressure and augmentation index. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(9 Pt 1):1168‐1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karamanoglu M, O'Rourke MF, Avolio AP, Kelly RP. An analysis of the relationship between central aortic and peripheral upper limb pressure waves in man. Eur Heart J. 1993;14:160‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takazawa K, Tanaka N, Takeda K, Kurosu F, Ibukiyama C. Underestimation of vasodilator effects of nitroglycerin by upper limb blood pressure. Hypertension. 1995;26(3):520‐523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams B, Lacy PS, Yan P, Hwee CN, Liang C, Ting CM. Development and validation of a novel method to derive central aortic systolic pressure from the radial pressure waveform using an N‐point moving average method. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(8):951‐961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM, et al. Differential impact of blood pressure‐lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study. Circulation. 2006;113(9):1213‐1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, et al. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2007;50(1):197‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang YI, Agnoletti D, Protogerou AD, et al. Radial late‐SBP as a surrogate for central SBP. J Hypertens. 2011;29(4):676‐681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pauca AL, Kon ND, O'Rourke MF. The second peak of the radial artery pressure wave represents aortic systolic pressure in hypertensive and elderly patients. BrJ Anaesth. 2004;92(5):651‐657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng HM, Sung SH, Shih YT, Chuang SY, Yu WC, Chen CH. Measurement of central aortic pulse pressure: noninvasive brachial cuff‐based estimation by a transfer function vs. a novel pulse wave analysis method. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25(11):1162‐1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen C‐H, Nevo E, Fetics B, et al. Estimation of central aortic pressure waveform by mathematical transformation of radial tonometry pressure: validation of generalized transfer function. Circulation. 1997;95:1827‐1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shih YT, Cheng HM, Sung SH, Hu WC, Chen CH. Application of the N‐point moving average method for brachial pressure waveform‐derived estimation of central aortic systolic pressure. Hypertension. 2014;63(4):865‐870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheng HM, Lang D, Tufanaru C, Pearson A. Measurement accuracy of non‐invasively obtained central blood pressure by applanation tonometry: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(5):1867‐1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Papaioannou TG, Karageorgopoulou TD, Sergentanis TN, et al. Accuracy of commercial devices and methods for noninvasive estimation of aortic systolic blood pressure a systematic review and meta‐analysis of invasive validation studies. J Hypertens. 2016;34(7):1237‐1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Picone DS, Schultz MG, Otahal P, et al. Accuracy of cuff‐measured blood pressure: systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(5):572‐586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Narayan O, Casan J, Szarski M, Dart AM, Meredith IT, Cameron JD. Estimation of central aortic blood pressure: a systematic meta‐analysis of available techniques. J Hypertens. 2014;32(9):1727‐1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shih YT, Cheng HM, Sung SH, Hu WC, Chen CH. Quantification of the calibration error in the transfer function‐derived central aortic blood pressures. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(12):1312‐1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sharman J, Stowasser M, Fassett R, Marwick T, Franklin S. Central blood pressure measurement may improve risk stratification. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22(12):838‐844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sharman JE, Marwick TH, Gilroy D, Otahal P, Abhayaratna WP, Stowasser M. Randomized trial of guiding hypertension management using central aortic blood pressure compared with best‐practice care: principal findings of the BP GUIDE study. Hypertension. 2013;62(6):1138‐1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Segers P, Mahieu D, Kips J, et al. Amplification of the pressure pulse in the upper limb in healthy, middle‐aged men and women. Hypertension. 2009;54(2):414‐420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kelly RP, Gibs HH, O'rourke MF, et al. Nitroglycerin has more favourable effects on left ventricular afterload than apparent from measurement of pressure in a peripheral artery. Eur Heart J. 1990;11:138‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Benetos A, Thomas F, Joly L, et al. Pulse pressure amplification a mechanical biomarker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(10):1032‐1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smulyan H, Safar ME. Blood pressure measurement: retrospective and prospective views. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(6):628‐634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rouxinol‐Dias A, Araujo S, Silva JA, Barbosa L, Polonia J. Association between ambulatory blood pressure values and central aortic pressure in a large population of normotensive and hypertensive patients. Blood Press Monit. 2018;23(1):24‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McEniery CM, Yasmin , Hall IR, Qasem A, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo‐Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(9):1753‐1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McEniery CM,Yasmin , McDonnell B, et al. Central pressure: variability and impact of cardiovascular risk factors: the Anglo‐Cardiff Collaborative Trial II. Hypertension. 2008;51(6):1476‐1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shih YT, Cheng HM, Sung SH, Chuang SY, Hu WC, Chen CH. Is noninvasive brachial systolic blood pressure an accurate estimate of central aortic systolic blood pressure? Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(11):1283‐1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Camacho F, Avolio A, Lovell NH. Estimation of pressure pulse amplification between aorta and brachial artery using stepwise multiple regression models. Physiol Meas. 2004;25(4):879‐889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilkinson IB, Mohammad NH, Tyrrell S, et al. Heart rate dependency of pulse pressure amplification and arterial stiffness. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15(1 Pt 1):24‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Albaladejo P, Copie X, Boutouyrie P, et al. Heart rate, arterial stiffness, and wave reflections in paced patients. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):949‐952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kollias A, Lagou S, Zeniodi ME, Boubouchairopoulou N, Stergiou GS. Association of central versus brachial blood pressure with target‐organ damage: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Hypertension. 2015;67(1):183‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chi C, Yu X, Auckle R, et al. Hypertensive target organ damage is better associated with central than brachial blood pressure: the Northern Shanghai Study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(12):1269‐1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kitagawa N, Okada H, Tanaka M, et al. Which measurement of blood pressure is more associated with albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes: central blood pressure or peripheral blood pressure? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(8):790‐795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. De Luca N, Asmar RG, London GM, O'Rourke MF, Safar ME. Selective reduction of cardiac mass and central blood pressure on low‐dose combination perindopril/indapamide in hypertensive subjects. J Hypertens. 2004;22(8):1623‐1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boutouyrie P, Bussy C, Hayoz D, et al. Local pulse pressure and regression of arterial wall hypertrophy during long‐term antihypertensive treatment. Circulation. 2000;101(22):2601‐2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pase MP, Stough C, Grima NA, et al. Blood pressure and cognitive function: the role of central aortic and brachial pressures. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(11):2173‐2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang K‐L, Cheng H‐M, Chuang S‐Y, et al. Central or peripheral systolic or pulse pressure: which best relates to target organs and future mortality? J Hypertens. 2009;27(3):461‐467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, O'Rourke MF, Safar ME, Baou K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all‐cause mortality with central haemodynamics: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(15):1865‐1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cheng H‐M, Chuang S‐Y, Sung S‐H, et al. Derivation and validation of diagnostic thresholds for central blood pressure measurements based on long‐term cardiovascular risks. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(19):1780‐1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ferdinand KC, Pool J, Weitzman R, Purkayastha D, Townsend R. Peripheral and central blood pressure responses of combination aliskiren/hydrochlorothiazide and amlodipine monotherapy in African American patients with stage 2 hypertension: the ATLAAST trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13(5):366‐375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Moura CS, Daskalopoulou SS, Levesque LE, et al. Comparison of the effect of thiazide diuretics and other antihypertensive drugs on central blood pressure: cross‐sectional analysis among nondiabetic patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015;17(11):848‐854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Protogerou AD, Stergiou GS, Vlachopoulos C, Blacher J, Achimastos A. The effect of antihypertensive drugs on central blood pressure beyond peripheral blood pressure. Part II: evidence for specific class‐effects of antihypertensive drugs on pressure amplification. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(3):272‐289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Manisty CH, Hughes AD. Meta‐analysis of the comparative effects of different classes of antihypertensive agents on brachial and central systolic blood pressure, and augmentation index. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(1):79‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kosmala W, Marwick TH, Stanton T, Abhayaratna WP, Stowasser M, Sharman JE. Guiding hypertension management using central blood pressure: effect of medication withdrawal on left ventricular function. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(3):319‐325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sharman JE. Central pressure should be used in clinical practice. Artery Res. 2015;9:1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):957‐967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matsui Y, Eguchi K, O'Rourke MF, et al. Differential effects between a calcium channel blocker and a diuretic when used in combination with angiotensin II receptor blocker on central aortic pressure in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;54(4):716‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Abdelmoneim Mohamed S, et al. A randomized pilot study of aortic waveform guided therapy in chronic heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(2):e000745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Picone DS, Schultz MG, Peng X, et al. Discovery of new blood pressure phenotypes and relation to accuracy of cuff devices used in daily clinical practice. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1239‐1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chuang S, Chou P, Hsu P, et al. Presence and progression of abdominal obesity are predictors of future high blood pressure and hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(8):788‐795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chuang SY, Chang HY, Cheng HM, Pan WH, Chen CH. Prevalence of hypertension defined by central blood pressure measured using a type II device in a nationally representative cohort. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31(3):346‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yu S, Xiong J, Lu Y, et al. The prevalence of central hypertension defined by a central blood pressure type I device and its association with target organ damage in the community‐dwelling elderly Chinese: the Northern Shanghai Study. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2018;12(3):211‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chuang SY, Chang HY, Cheng HM, Pan WH, Chen CH. Impacts of the new 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline on the prevalence of brachial hypertension and its concordance with central hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2019;32(4):409‐417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu J, Cheng HM, Chen CH, Sung SH, Hahn JO, Mukkamala R. Patient‐specific oscillometric blood pressure measurement: validation for accuracy and repeatability. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2017;5:1900110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Campbell NRC, Gelfer M, Stergiou GS, et al. A call to regulate manufacture and marketing of blood pressure devices and cuffs: a position statement from the world hypertension league, international society of hypertension and supporting hypertension organizations. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(5):378‐380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mitchell GF, Hwang S‐J, Larson MG, et al. Transfer function‐derived central pressure and cardiovascular disease events: the Framingham Heart Study. J Hypertens. 2016;34(8):1528‐1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Laurent S, Sharman J, Boutouyrie P. Central versus peripheral blood pressure: finding a solution. J Hypertens. 2016;34(8):1497‐1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Laurent S, Briet M, Boutouyrie P. Arterial stiffness as surrogate end point: needed clinical trials. Hypertension. 2012;60(2):518‐522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lu TM, Hsu NW, Chen YH, et al. Pulsatility of ascending aorta and restenosis after coronary angioplasty in patients >60 years of age with stable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(9):964‐968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. London GM, Blacher J, Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, Safar ME. Arterial wave reflections and survival in end‐stage renal failure. Hypertension. 2001;38(3):434‐438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Safar ME, Blacher J, Pannier B, et al. Central pulse pressure and mortality in end‐stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2002;39(3):735‐738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ueda H, Hayashi T, Tsumura K, Yoshimaru K, Nakayama Y, Yoshikawa J. The timing of the reflected wave in the ascending aortic pressure predicts restenosis after coronary stent placement. Hypertens Res. 2004;27(8):535‐540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chirinos JA, Zambrano JP, Chakko S, et al. Aortic pressure augmentation predicts adverse cardiovascular events in patients with established coronary artery disease. Hypertension. 2005;45(5):980‐985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Weber T, Auer J, O'Rourke MF, et al. Increased arterial wave reflections predict severe cardiovascular events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(24):2657‐2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Dart AM, Gatzka CD, Kingwell BA, et al. Brachial blood pressure but not carotid arterial waveforms predict cardiovascular events in elderly female hypertensives. Hypertension. 2006;47(4):785‐790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Covic A, Mardare N, Gusbeth‐Tatomir P, Prisada O, Sascau R, Goldsmith DJ. Arterial wave reflections and mortality in haemodialysis patients–only relevant in elderly, cardiovascularly compromised? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(10):2859‐2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jankowski P, Kawecka‐Jaszcz K, Czarnecka D, et al. Pulsatile but not steady component of blood pressure predicts cardiovascular events in coronary patients. Hypertension. 2008;51:848‐855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Chirinos JA, Kips JG, Jacobs DR Jr, et al. Arterial wave reflections and incident cardiovascular events and heart failure: MESA (Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(21):2170‐2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wassertheurer S, Baumann M. Assessment of systolic aortic pressure and its association to all cause mortality critically depends on waveform calibration. J Hypertens. 2015;33(9):1884‐1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Guerin AP, Pannier BM, Marchais SJ, Metivier F, Safar M, London GM. Effects of antihypertensive agents on carotid pulse contour in humans. J Hum Hypertens. 1992;6(Suppl. 2):S37‐S40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. London GM, Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, Safar ME, Cuche JL. Cardiac hypertrophy, aortic compliance, peripheral resistance, and wave reflection in end‐stage renal disease. Comparative effects of ACE inhibition and calcium channel blockade. Circulation. 1994;90(6):2786‐2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chen C‐H, Ting C‐T, Lin S‐J, et al. Different effects of fosinopril and atenolol on wave reflections in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1995;25(5):1034‐1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mahmud A, Feely J. Favourable effects on arterial wave reflection and pulse pressure amplification of adding angiotensin II receptor blockade in resistant hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14(9):541‐546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Asmar R. Effect of telmisartan on arterial distensibility and central blood pressure in patients with mild to moderate hypertension and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2001;2(Suppl. 2):S8‐S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Asmar RG, London GM, O'Rourke ME, Safar ME. Coordinators RP, Investigators. Improvement in blood pressure, arterial stiffness and wave reflections with a very‐low‐dose perindopril/indapamide combination in hypertensive patient: a comparison with atenolol. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):922‐926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mitchell GF, Izzo JL, Lacourcière Y, et al. Omapatrilat reduces pulse pressure and proximal aortic stiffness in patients with systolic hypertension: results of the conduit hemodynamics of omapatrilat international research study. Circulation. 2002;105(25):2955‐2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Deary AJ, Schumann AL, Murfet H, Haydock SF, Foo RS, Brown MJ. Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled crossover comparison of five classes of antihypertensive drugs. J Hypertens. 2002;20(4):771‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. de Luca N, Asmar RG, London GM, O'Rourke MF, Safar ME, Investigators RP. Selective reduction of cardiac mass and central blood pressure on low‐dose combination perindopril/indapamide in hypertensive subjects. J Hypertens. 2004;22(8):1623‐1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Neal DA, Brown MJ, Wilkinson IB, Byrne CD, Alexander GJ. Hemodynamic effects of amlodipine, bisoprolol, and lisinopril in hypertensive patients after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;77(5):748‐750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. London GM, Asmar RG, O'Rourke MF, Safar ME, Investigators RP. Mechanism(s) of selective systolic blood pressure reduction after a low‐dose combination of perindopril/indapamide in hypertensive subjects: comparison with atenolol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(1):92‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Morgan T, Lauri J, Bertram D, Anderson A. Effect of different antihypertensive drug classes on central aortic pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(2):118‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mahmud A, Feely J. Aldosterone‐to‐renin ratio, arterial stiffness, and the response to aldosterone antagonism in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(1):50‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Dart AM, Cameron JD, Gatzka CD, et al. Similar effects of treatment on central and brachial blood pressures in older hypertensive subjects in the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Trial. Hypertension. 2007;49(6):1242‐1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Jiang XJ, O'Rourke MF, Zhang YQ, He XY, Liu LS. Superior effect of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor over a diuretic for reducing aortic systolic pressure. J Hypertens. 2007;25(5):1095‐1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Dhakam Z, Mceniery C, Yasmin, Cockcroft J, Brown M, Wilkinson I. Atenolol and eprosartan: differential effects on central blood pressure and aortic pulse wave velocity. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(2):214‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Schneider MP, Delles C, Klingbeil AU, et al. Effect of angiotensin receptor blockade on central haemodynamics in essential hypertension: results of a randomised trial. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2008;9(1):49‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Dhakam Z, Yasmin, McEniery CM, Burton T, Brown MJ, Wilkinson IB. A comparison of atenolol and nebivolol in isolated systolic hypertension. J Hypertens. 2008;26(2):351‐356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mahmud A, Feely J. Beta‐blockers reduce aortic stiffness in hypertension but nebivolol, not atenolol, reduces wave reflection. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(6):663‐667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mackenzie IS, McEniery CM, Dhakam Z, Brown MJ, Cockcroft JR, Wilkinson IB. Comparison of the effects of antihypertensive agents on central blood pressure and arterial stiffness in isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;54(2):409‐413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Boutouyrie P, Achouba A, Trunet P, Laurent S, Group ET. Amlodipine‐valsartan combination decreases central systolic blood pressure more effectively than the amlodipine‐atenolol combination: the EXPLOR study. Hypertension. 2010;55(6):1314‐1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Doi M, Miyoshi T, Hirohata S, et al. Combination therapy of calcium channel blocker and angiotensin II receptor blocker reduces augmentation index in hypertensive patients. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339(5):433‐439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kaufman R, Nunes I, Bolognese JA, et al. Single‐dose effects of isosorbide mononitrate alone or in combination with losartan on central blood pressure. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4(6):311‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Cockburn JA, Brett SE, Guilcher A, Ferro A, Ritter JM, Chowienczyk PJ. Differential effects of beta‐adrenoreceptor antagonists on central and peripheral blood pressure at rest and during exercise. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(4):329‐335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Manisty CH, Zambanini A, Parker KH, et al. Differences in the magnitude of wave reflection account for differential effects of amlodipine‐ versus atenolol‐based regimens on central blood pressure: an Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcome Trial substudy. Hypertension. 2009;54(4):724‐730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Takenaka T, Seto T, Okayama M, et al. Long‐term effects of calcium antagonists on augmentation index in hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled study. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(5):416‐423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Qasem AA, et al. Effect of aliskiren treatment on endothelium‐dependent vasodilation and aortic stiffness in essential hypertensive patients. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(12):1530‐1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Izzo JL Jr, Rajpal M, Karan S, Srikakarlapudi S, Osmond PJ. Hemodynamic and central blood pressure differences between carvedilol and valsartan added to lisinopril at rest and during exercise stress. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6(2):117‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Vitale C, Marazzi G, Iellamo F, et al. Effects of nebivolol or irbesartan in combination with hydrochlorothiazide on vascular functions in newly‐diagnosed hypertensive patients: the NINFE (Nebivololo, Irbesartan Nella Funzione Endoteliale) study. Int J Cardiol. 2012;155(2):279‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Takami T, Saito Y. Effects of Azelnidipine plus OlmesaRTAn versus amlodipine plus olmesartan on central blood pressure and left ventricular mass index: the AORTA study. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:383‐390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ruilope L, Schaefer A. The fixed‐dose combination of olmesartan/amlodipine was superior in central aortic blood pressure reduction compared with perindopril/amlodipine: a randomized, double‐blind trial in patients with hypertension. Adv Ther. 2013;30(12):1086‐1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Fogari R, Mugellini A, Zoppi A, et al. Effect of imidapril versus ramipril on urinary albumin excretion in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14(18):2463‐2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Koumaras C, Tziomalos K, Stavrinou E, et al. Effects of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors and beta‐blockers on markers of arterial stiffness. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8(2):74‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Eeftinck Schattenkerk DW, van den Bogaard B, Cammenga M, Westerhof BE, Stroes ES, van den Born BJ. Lack of difference between nebivolol/hydrochlorothiazide and metoprolol/hydrochlorothiazide on aortic wave augmentation and central blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2013;31(12):2447‐2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Radchenko GD, Sirenko YM, Kushnir SM, Torbas OO, Dobrokhod AS. Comparative effectiveness of a fixed‐dose combination of losartan + HCTZ versus bisoprolol + HCTZ in patients with moderate‐to‐severe hypertension: results of the 6‐month ELIZA trial. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:535‐549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ihm SH, Jeon HK, Chae SC, et al. Benidipine has effects similar to losartan on the central blood pressure and arterial stiffness in mild to moderate essential hypertension. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126(11):2021‐2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Agnoletti D, Zhang Y, Borghi C, Blacher J, Safar ME. Effects of antihypertensive drugs on central blood pressure in humans: a preliminary observation. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26(8):1045‐1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Takami T, Saito Y. Azelnidipine plus olmesartan versus amlodipine plus olmesartan on arterial stiffness and cardiac function in hypertensive patients: a randomized trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:175‐183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Hare JL, Sharman JE, Leano R, Jenkins C, Wright L, Marwick TH. Impact of spironolactone on vascular, myocardial, and functional parameters in untreated patients with a hypertensive response to exercise. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26(5):691‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Park S, Rhee M‐Y, Lee SY, et al. A prospective, randomized, open‐label, active‐controlled, clinical trial to assess central haemodynamic effects of bisoprolol and atenolol in hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2013;31(4):813‐819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Dorresteijn JAN, Schrover IM, Visseren FLJ, et al. Differential effects of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibition, sympathoinhibition and diuretic therapy on endothelial function and blood pressure in obesity‐related hypertension: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over trial. J Hypertens. 2013;31(2):393‐403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Matthesen SK, Larsen T, Vase H, Lauridsen TG, Jensen JM, Pedersen EB. Effect of amiloride and spironolactone on renal tubular function and central blood pressure in patients with arterial hypertension during baseline conditions and after furosemide: a double‐blinded, randomized, placebo‐controlled crossover trial. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2013;35(5):313‐324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Parati G, Revera M, Giuliano A, et al. Effects of acetazolamide on central blood pressure, peripheral blood pressure, and arterial distensibility at acute high altitude exposure. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(10):759‐766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Park JB, Ha JW, Jung HO, Rhee MY, Investigators F. Randomized trial comparing the effects of a low‐dose combination of nifedipine GITS and valsartan versus high‐dose monotherapy on central hemodynamics in patients with inadequately controlled hypertension: FOCUS study. Blood Press Monit. 2014;19(5):294‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Dillinger J‐G, Maher V, Vitale C, et al. Impact of Ivabradine on Central Aortic Blood Pressure and Myocardial Perfusion in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Hypertension. 2015;66(6):1138‐1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Ghiadoni L, Bruno RM, Cartoni G, et al. Combination therapy with lercanidipine and enalapril reduced central blood pressure augmentation in hypertensive patients with metabolic syndrome. Vascul Pharmacol. 2017;92:16‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Metoki H, Obara T, Asayama K, et al. Differential effects of angiotensin II receptor blocker and losartan/hydrochlorothiazide combination on central blood pressure and augmentation index. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2015;37(4):294‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Redon J, Pichler G,Missed Dose Study G . Comparative study of the efficacy of olmesartan/amlodipine vs. perindopril/amlodipine in peripheral and central blood pressure parameters after missed dose in type 2 diabetes. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(9):1055‐1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Rimoldi SF, Messerli FH, Cerny D, et al. Selective heart rate reduction with Ivabradine increases central blood pressure in stable coronary artery disease. Hypertension. 2016;67(6):1205‐1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Rosenbaek JB, Al Therwani S, Jensen JM, et al. Effect of sodium nitrite on renal function and sodium and water excretion and brachial and central blood pressure in healthy subjects: a dose‐response study. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;313(2):F378‐F387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Suojanen L, Haring A, Tikkakoski A, et al. Haemodynamic influences of bisoprolol in hypertensive middle‐aged men: a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled cross‐over study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;121(2):130‐137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Schreglmann SR, Büchele F, Sommerauer M, et al. Pyridostigmine bromide versus fludrocortisone in the treatment of orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson's disease—a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(4):545‐551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Farag SM, Rabea HM, Mahmoud HB. Effect of amlodipine/valsartan versus nebivolol/valsartan fixed dose combinations on peripheral and central blood pressure. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2018;25(4):407‐413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Rosenbaek JB, Pedersen EB, Bech JN. The effect of sodium nitrite infusion on renal function, brachial and central blood pressure during enzyme inhibition by allopurinol, enalapril or acetazolamide in healthy subjects: a randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, crossover study. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Georgianou E, Georgianos PI, Petidis K, Markakis K, Zografou I, Karagiannis A. Effect of nebivolol and olmesartan on 24‐hour brachial and aortic blood pressure in the acute stage of ischemic stroke. Int J Hypertens. 2019;2019:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]