Abstract

The authors assessed the prognostic value of daytime and nighttime blood pressure (BP) in adult (≤65 years) or old (> 65 years) women or men with treated hypertension. Cardiovascular outcomes were evaluated in 2264 patients. During the follow‐up (mean 10 years), 523 cardiovascular events occurred. After adjustment for covariates, both daytime and nighttime systolic BP were always associated with outcomes, that is, hazard ratio (95% confidence interval per 10 mm Hg increment) 1.22 (1.04‐1.43) and 1.20 (1.04‐1.37), respectively, in adult women, 1.30 (1.18‐1.43) and 1.21 (1.10‐1.33), respectively, in adult men, 1.21 (1.10‐1.33) and 1.18 (1.07‐1.31), respectively, in old women, and 1.16 (1.01‐1.33) and 1.28 (1.14‐1.44), respectively, in old men. When daytime and nighttime systolic BP were further and mutually adjusted, daytime and nighttime BP had comparable prognostic value in adult and old women, daytime BP remained associated with outcomes in adult men (hazard ratio 1.40, 95% confidence interval 1.13‐1.74 per 10 mm Hg increment), and nighttime BP remained associated with outcomes in old men (hazard ratio 1.35, 95% confidence interval 1.11‐1.64 per 10 mm Hg increment). Daytime and nighttime systolic BP have similar prognostic impact in adult and old women with treated hypertension, whereas daytime BP is a stronger predictor of risk in adult men and nighttime BP is a stronger predictor of risk in old men.

Keywords: adult, ambulatory blood pressure, cardiovascular risk, hypertension, old, sex

1. INTRODUCTION

Various studies have shown that ambulatory blood pressure (BP) is superior to clinic BP in predicting cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Noninvasive ambulatory BP monitoring gives the opportunity to detect daytime, nighttime, and 24‐hour BP, circadian BP changes, BP variability, and ambulatory BP phenotypes. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

Concerning daytime and nighttime BP, both of them have been shown to be associated with cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 and in general populations. 22 , 23 In hypertensive individuals, some studies 11 , 13 , 14 , 17 reported substantially similar prognostic value of daytime and nighttime BP, whereas others 12 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 reported superiority of nighttime BP over daytime BP in predicting outcomes, particularly when mutually adjusted in the same model. 12 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 20 , 21

Daytime and nighttime BP and their relationship may change with aging. Indeed, in adult subjects daytime BP may be influenced by physical activity and job stress, generally no longer present to the same extent in the elderly, whereas old patients generally have reduced nighttime BP dip and higher nighttime BP. 24 , 25 Another debated issue is whether the prognostic relevance of ambulatory BP parameters may be different in women and men. 18 , 26 , 27

Two studies 13 , 18 evaluated the prognostic impact of daytime and nighttime BP in younger and older hypertensive patients and two studies assessed their prognostic value in women and men of hypertensive 18 or general 27 populations with results not always unanimous.

However, to our knowledge, no study apparently evaluated the prognostic relevance of daytime and nighttime BP in younger and older women and men analyzed separately. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the prognostic value of daytime and nighttime BP in adult (≤65 years) and old (>65 years) women and men with treated hypertension.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

The authors studied 2264 sequential treated hypertensive subjects aged 30‐90 years who were prospectively recruited from December 1992 to December 2012. All these patients had been referred to our hospital outpatient clinic for evaluation of BP control. One hundred and three patients were lost during follow‐up. Subjects with secondary hypertension were excluded. All the individuals underwent clinical evaluation, electrocardiogram, routine laboratory tests, echocardiographic examination, and noninvasive ambulatory BP monitoring. Study population came from the same geographical area (Chieti and Pescara, Abruzzo, Italy). The study was in accordance with the Second Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review committee. Subjects gave informed consent.

2.2. Clinic BP measurement

Clinic BP was recorded by a physician using a mercury sphygmomanometer and appropriate‐sized cuffs. Measurements were performed in triplicate, 2 minutes apart, and the mean value was used as the BP for the visit. Clinic systolic and diastolic BP were defined as normal when <140/90 mm Hg.

2.3. Ambulatory BP monitoring

Ambulatory BP monitoring was performed by using a portable noninvasive recorder (SpaceLabs 90 207, Redmond, WA) on a typical day, within 1 week from clinic visit. Each time a reading was taken, patients were instructed to remain motionless and to report their activity on a diary sheet. Technical aspects have been previously reported. 28 Ambulatory BP readings were obtained at 15‐min intervals from 6 AM to midnight, and at 30‐min intervals from midnight to 6 AM. The authors evaluated the following ambulatory BP parameters: daytime (awake period as reported in the diary), nighttime (asleep period as reported in the diary), and 24‐hour systolic and diastolic BP. Recordings were automatically edited (ie, excluded) if systolic BP was > 260 or < 70 mm Hg or if diastolic BP was > 150 or < 40 mm Hg and pulse pressure was > 150 or < 20 mm Hg. All the subjects had recordings of good quality (at least 70% of valid readings during the 24‐hour period, at least 20 valid readings while awake with at least 2 valid readings per hour and at least 7 valid readings while asleep with at least 1 valid reading per hour), in line with minimum requirement suggested by the European Society of Hypertension. 29 In our center, less than 5% of subjects had recordings of poor quality.

2.4. Echocardiography

Left atrial (LA) and left ventricular (LV) measurements and calculation of LV mass were performed according to standardized methods. 30 LA diameter (cm) was indexed by body surface area (m2) and LA enlargement was defined as LA diameter/body surface area ≥2.4 cm/m2. 31 LV mass was indexed by height2.7 and LV hypertrophy was defined as LV mass/height2.7 >50 g/m2.7 in men and >47 g/m2.7 in women. 31 LV ejection fraction was estimated using the Teichholz formula or the Simpson rule and defined as low when it was <50%. 30

2.5. Follow‐up

Subjects were followed up in our hospital outpatient clinic or by their family doctors.

The occurrence of events was recorded during follow‐up visits or by telephone interview of the family doctor or the patient or a family member, followed by a visit if the patient was alive. Later, medical records were obtained to confirm the events. In this report, the authors evaluated a combined endpoint including coronary events (sudden death, fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction, and coronary revascularization), fatal and nonfatal stroke, heart failure requiring hospitalization, and peripheral revascularization. Outcomes were defined according to standard criteria as previously reported. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 The authors considered only the first event and recurrent events were excluded.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were used. Comparison between groups was performed by using one‐way ANOVA, followed by a multiple comparison test, and chi‐square or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate. Event rates are expressed as the number of events per 100 patient‐years based on the ratio of the observed number of events to the total number of patient‐years of exposure up to the terminating event or censor. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan‐Meier product‐limit method and compared by the log rank test. Cox regression analysis was used to estimate association of factors with outcome. First, the authors evaluated univariate association between combined endpoint and various covariates, including daytime and nighttime BP. Then, multiple regression analysis was performed reporting in the final model variables that were significantly associated with outcome in univariate analysis. The forced entry model was used. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05. Analyses were made with the SPSS 21 software package (SPSS Inc Chicago, IL).

3. RESULTS

Characteristics of study groups are reported in Table 1. Age was different among the groups by definition. Body mass index was lower in old than in adult patients. Prevalence of smoking habit was highest in adult men and was lower in elderly than in adult subjects. Prevalence of previous events was highest in old men. Prevalence of diabetes was higher in elderly than in adult individuals. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was lower in old than in adult patients. Low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were lowest in elderly men. Prevalence of LV hypertrophy was lowest in adult women. Prevalence of LA enlargement and asymptomatic LV systolic dysfunction were higher in old than in adult subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Parameter | (1) Women | (2) Men | (3) Women | (4) Men |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 y | <65 y | >65 y | >65 y | |

| n | 776 | 743 | 441 | 304 |

| Age, years | 54 ± 8 | 53 ± 8 | 73 ± 5 | 72 ± 5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28 ± 5 | 28 ± 4 | 27 ± 4* , ‡ | 27 ± 3* , ‡ |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 142 (18) | 191(26)* | 29 (7)* , ‡ | 44 (14)‡ , † |

| FHPCVD, n (%) | 118 (15) | 96 (13) | 53 (12) | 30 (10) |

| Previous events, n (%) | 15 (2) | 51 (7)* | 25 (6)* | 50 (16)* , ‡ , † |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 46 (6) | 40 (5) | 63 (14)* , ‡ | 51 (17)* , ‡ |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 76 ± 20 | 84 ± 20* | 58 ± 13* , ‡ | 68 ± 15* , ‡ , † |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 130 ± 30 | 128 ± 31 | 129 ± 28 | 123 ± 30* |

| LV hypertrophy, n (%) | 177 (23) | 214 (29)* | 146 (33)* | 99 (33)* |

| LA enlargement, n (%) | 88 (11) | 109 (15) | 100 (23)* , ‡ | 68 (22)* , ‡ |

| ALVSD, n (%) | 9 (1) | 19 (3) | 19 (4)* | 17 (6)* |

Previous events included cerebral or cardiac events or peripheral revascularization. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose > 125 mg/dl or use of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin.

Abbreviations: ALVSD, asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction < 50%); BMI, body mass index calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate calculated by the MDRD equation; FHPCVD, family history of premature cardiovascular disease defined as an event occurred in men aged less than 55 years and in women aged less than 65 years; LA, left atrial; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein calculated by the Friedewald's formula; LV, left ventricular.

P < .05 vs 1.

P < .05 vs 2.

P < .05 vs 3.

BP values of study population are reported in Table 2. Systolic and diastolic BP were higher in adult men than in adult women. Systolic BP was higher in old than in adult individuals. Diastolic BP was lower in elderly than in adult patients.

Table 2.

Baseline blood pressure of study population

| Parameter | (1) Women | (2) Men | (3) Women | (4) Men |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 y | <65 y | >65 y | >65 y | |

| Clinic SBP, mm Hg | 145 ± 16 | 146 ± 15 | 153 ± 19*,‡ | 150 ± 17*,‡ |

| Clinic DBP, mm Hg | 90 ± 10 | 93 ± 9* | 86 ± 10*,‡ | 86 ± 11*,‡ |

| Daytime SBP, mm Hg | 132 ± 13 | 136 ± 13* | 136 ± 15* | 137 ± 14* |

| Daytime DBP, mm Hg | 81 ± 9 | 86 ± 9* | 76 ± 8*,‡ | 78 ± 9*,‡ , † |

| Nighttime SBP, mm Hg | 117 ± 14 | 120 ± 14* | 124 ± 16*,‡ | 126 ± 16*,‡ |

| Nighttime DBP, mm Hg | 69 ± 9 | 73 ± 9* | 65 ± 9*,‡ | 69 ± 9‡ , † |

| 24‐hour SBP, mm Hg | 128 ± 13 | 131 ± 13* | 132 ± 14* | 133 ± 14* |

| 24‐hour DBP, mm Hg | 77 ± 8 | 82 ± 8* | 73 ± 8*,‡ | 75 ± 8*,‡ , † |

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

P < .05 vs 1.

P < .05 vs 2.

P < .05 vs 3.

Baseline antihypertensive therapy is reported in Table 3. Use of diuretics was highest in old women. Use of beta‐blockers was lowest in elderly men. Use of calcium channel blockers was highest in adult and old men. Use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors was higher in elderly than in adult patients. Use of alpha‐blockers was highest in old men. Triple therapy was highest in elderly women. Use of aspirin and statin was higher in old than in adult subjects.

Table 3.

Baseline therapy of study population

| Parameter | (1) Women | (2) Men | (3) Women | (4) Men |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 y | <65 y | >65 y | >65 y | |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 420 (54) | 378 (51) | 275 (62)* , ‡ | 156 (51)† |

| Beta‐blocker, n (%) | 312 (40) | 232 (31)* | 147 (33) | 63 (21)* , ‡,† |

| CCB, n (%) | 213 (27) | 283 (38)* | 145 (33) | 115 (38)* |

| ACE‐I, n (%) | 338 (44) | 348 (47) | 227 (51)* | 169 (56)* |

| ARB, n (%) | 163 (21) | 167 (22) | 119 (27) | 69 (23) |

| Alpha‐blocker, n (%) | 82 (11) | 112 (15) | 50 (11) | 54 (18)* |

| Single therapy, n (%) | 220 (28) | 173 (23) | 95 (22) | 85 (28) |

| Double therapy, n (%) | 403 (52) | 396 (53) | 205 (47) | 139 (46) |

| Triple therapy, n (%) | 153 (20) | 174 (23) | 141 (32)* , ‡ | 80 (26) |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 62 (8) | 91 (12)* | 114 (26)* , ‡ | 89 (29)* , ‡ |

| Statin, n (%) | 46 (6) | 60 (8) | 53 (12)* | 34 (11)* |

Abbreviations: ACE‐I, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

P < .05 vs 1.

P < .05 vs 2.

P < .05 vs 3.

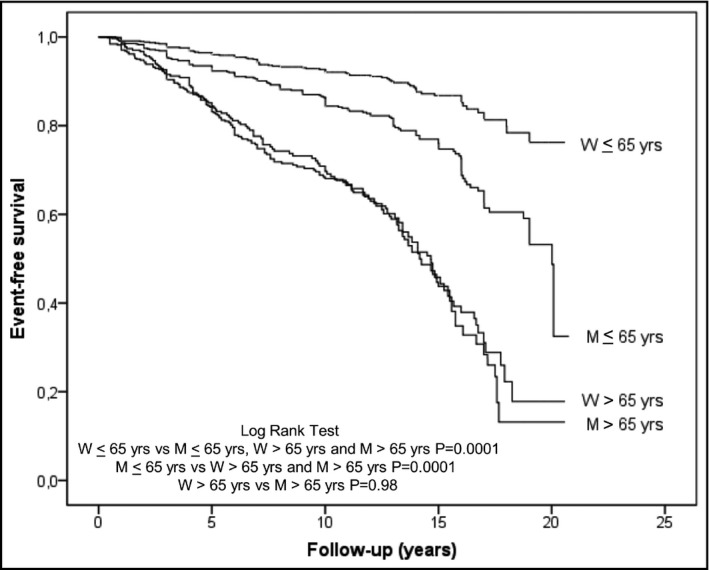

During the follow‐up (10 ± 5 years, range 0.4‐21 years), 523 events occurred in the global population. There were 81 events in adult women, 158 events in adult men, 169 events in old women, and 115 events in old men. Event rates and event‐free survival curves of the study groups are reported in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Event rate of study groups. M, men; W, women; yrs, years

Figure 2.

Event‐free survival curves of study groups. M, men; W, women; yrs, years

First, the authors evaluated univariate association of clinic, daytime, nighttime, and 24‐hour systolic and diastolic BP with cardiovascular outcome. Systolic BP parameters were significantly associated with outcome in all the groups. Diastolic BP parameters tended to be associated with outcome, but did not attain statistical significance, in adult women, were associated with outcome in adult men, and were not associated with outcome in old women and men. Thus, the authors report only data about systolic BP parameters in univariate and multivariate analyses (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of clinic, daytime, nighttime and 24‐h systolic blood pressure with cardiovascular risk

| Group | Unadjusted | Adjusted (Model 1) | Adjusted (Model 2) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic SBP | Daytime SBP | Nighttime SBP | 24‐h SBP | Clinic SBP | Daytime SBP | Nighttime SBP | 24‐h SBP | Clinic SBP | Daytime SBP | Nighttime SBP | |

| (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | (10 mm Hg) | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

|

Women <65 y |

1.32 (1.18‐1.49) |

1.35 (1.18‐1.55) |

1.31 (1.14‐1.50) |

1.38 (1.18‐1.61) |

1.17 (1.02‐1.35) |

1.22 (1.04‐1.43) |

1.20 (1.04‐1.37) |

1.25 (1.06‐1.46) |

1.07 (0.88‐1.30) |

1.11 (0.84‐1.45) |

1.06 (0.84‐1.34) |

|

Men <65 y |

1.16 (1.05‐1.28) |

1.32 (1.20‐1.46) |

1.25 (1.13‐1.37) |

1.32 (1.20‐1.46) |

1.12 (1.01‐1.23) |

1.30 (1.18‐1.43) |

1.21 (1.10‐1.33) |

1.28 (1.16‐1.42) |

0.89 (0.77‐1.02) |

1.40 (1.13‐1.74) |

1.02 (0.87‐1.19) |

|

Women >65 y |

1.18 (1.10‐1.28) |

1.34 (1.21‐1.47) |

1.32 (1.22‐1.43) |

1.36 (1.24‐1.50) |

1.10 (1.02‐1.19) |

1.21 (1.10‐1.33) |

1.18 (1.07‐1.31) |

1.22 (1.11‐1.35) |

0.99 (0.88‐1.12) |

1.12 (0.90‐1.38) |

1.11 (0.94‐1.29) |

|

Men >65 y |

1.05 (0.93‐1.18) |

1.21 (1.05‐1.39) |

1.28 (1.14‐1.44) |

1.26 (1.10‐1.44) |

0.97 (0.86‐1.09) |

1.16 (1.01‐1.33) |

1.28 (1.14‐1.44) |

1.23 (1.07‐1.41) |

0.83 (0.71‐0.98) |

1.05 (0.83‐1.33) |

1.35 (1.11‐1.64) |

Model 1: adjusted for age, smoke, family history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, previous events, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate, left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement and asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Model 2: adjusted for the same variables plus adjustment for daytime and nighttime blood pressure for clinic blood pressure, adjustment for clinic and nighttime blood pressure for daytime blood pressure and adjustment for clinic and daytime blood pressure for nighttime blood pressure.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Daytime and nighttime systolic BP had a similar prognostic impact in adult and old women in univariate analysis, when adjusted for other covariates and when further adjusted for each other. In adult men, daytime systolic BP tended to be more strongly associated with risk than nighttime systolic BP in univariate analysis and multivariate analysis adjusted for other covariates. When further adjusted for each other, daytime systolic BP remained significantly associated with outcome. In elderly men, nighttime systolic BP tended to be more strongly associated with risk than daytime systolic BP in univariate analysis and multivariate analysis adjusted for other covariates. When further adjusted for each other, nighttime systolic BP remained significantly associated with outcome (Table 4).

In a model with clinic systolic BP, covariates, and daytime systolic BP, adding nighttime systolic BP did not change the −2LL value in adult men but significantly reduced it (P < .01) in old men. In a model with clinic systolic BP, covariates, and nighttime systolic BP, adding daytime systolic BP significantly reduced the −2LL value (P < .01) in adult men but did not change it in old men.

When the authors analyzed the impact of daytime and nighttime diastolic BP in adult men, that is the only group in which diastolic BP was associated with outcome, after adjustment for various covariates and for each other BP indexes, daytime diastolic BP remained significantly associated with outcome (hazard ratio 1.63, 95% confidence interval 1.17‐2.28, per 10 mm Hg increment).

In a sensitivity analysis in which adult and old patients were defined by a cutoff value of 60 years, in place of 65 years, the results were substantially similar.

In the study population, by using cutoff values of 140/90 mm Hg for clinic systolic/diastolic BP, the percentage of patients with controlled BP was 33%. By using cutoff values of 135/85 mm Hg for daytime systolic/diastolic BP, the percentage of patients with controlled daytime BP was 47%, and by using cutoff values of 120/70 mm Hg for nighttime systolic/diastolic BP, the percentage of patients with controlled nighttime BP was 37%.

By using a cutoff value of 135 mm Hg for daytime systolic BP only, the percentage of patients with controlled daytime systolic BP was 62.4%, 50.6%, 51.7%, and 49.7% in adult women, adult men, old women, and old men, respectively. By using a cutoff value of 120 mm Hg for nighttime systolic BP only, the percentage of patients with controlled nighttime systolic BP was 59.9%, 53.7%, 45.6%, and 44.4% in adult women, adult men, old women, and old men, respectively. If the authors included controlled/uncontrolled BP for both daytime and nighttime systolic BP as a categorical covariate in multivariate analysis (Model 2), results remained substantially the same in all the groups. Particularly, in adult men, the hazard ratio (95% confidence interval per 10 mm Hg increment) was 1.38 (1.07‐1.78) and 1.00 (0.82‐1.22) for daytime and nighttime systolic BP, respectively, and in old men, the hazard ratio (95% confidence interval per 10 mm Hg increment) was 0.95 (0.71‐1.28) and 1.35 (1.05‐1.74) for daytime and nighttime systolic BP, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

This study shows that the prognostic value of daytime and nighttime systolic BP may be different according to age and sex. Indeed, in predicting prognosis, daytime and nighttime BP were similar in adult and old women, whereas daytime BP was a stronger predictor of risk in adult men and nighttime BP was a stronger predictor of risk in old men.

Two studies 13 , 18 assessed the prognostic impact of daytime and nighttime BP in younger and older subjects. One study 13 including untreated hypertensive individuals showed that daytime and nighttime BP had a similar prognostic value in both adult and old patients. The other study, 18 including untreated and treated hypertensive patients, reported that nighttime BP was superior to daytime BP in predicting prognosis in both adult and old patients. Two studies 18 , 27 evaluated the prognostic significance of daytime and nighttime BP in women and men. One study, 18 including untreated and treated hypertensive patients, showed that nighttime BP was superior to daytime BP in predicting prognosis in both women and men. The other study, 27 evaluating general populations, reported that nighttime BP was superior to daytime BP in predicting outcomes in women, but not in men. Differences between our study and previous ones 13 , 18 , 27 may be related to patients’ characteristics, follow‐up length, number of events, and study design. For instance, compared to the study evaluating treated hypertensive patients separately, 18 our study analyzed the prognostic value of daytime and nighttime BP in adult and old women and men separately, had a longer follow‐up and included more events.

It is tempting to explain the prognostic influence of daytime and nighttime BP in adult and old men, respectively, in our study. Ambulatory BP is the result of basal BP, environmental influences and habits. In this context, job strain is one of the most relevant factors. 36 Adverse effect of work stress on BP has been reported in both men and women but it is more consistent in men. 36 , 37 Though the impact of job strain on BP may persist during the 24‐hour period, various studies have shown that BP tends to be highest at work and during the day. 36 , 37 , 38 Another factor that adversely affects mainly work or daytime BP is smoking habit 36 , 39 , 40 which is more frequent in men who are also more frequently heavy smokers. 39 The aforesaid aspects could partly explain why daytime BP is a stronger predictor of risk than nighttime BP in adult men. Nighttime BP may be increased by various factors, including autonomic nervous system dysfunction, salt sensitivity, sleep‐disordered breathing, and nocturia. 41 The prevalence of these factors tends to increase with aging and some of them, such as sleep‐disordered breathing and nocturia, are more frequent in older men. 42 , 43 The abovementioned aspects could partly explain why nighttime BP is a stronger predictor of risk than daytime BP in old men.

This study has some limitations. First, the authors studied only Caucasian subjects and our results cannot be applied to other ethnic groups. Second, it cannot be excluded that some patients with apparently controlled BP were not referred to our center and our results cannot be extrapolated to all treated hypertensive patients. However, our study population included a substantial portion of patients with controlled BP; thus, it is unlikely that the inclusion of potentially not referred patients might have changed our results. Third, the independent prognostic value of various factors potentially influencing daytime and nighttime BP according to age and sex could not be assessed in this population. However, this aspect does not necessarily weaken the prognostic impact of daytime and nighttime BP in adult and old men, respectively. Fourth, time of antihypertensive drug administration was not systematically recorded in all the patients.

In conclusion, this study shows that the prognostic value of daytime and nighttime systolic BP may be different according to age and sex. Daytime and nighttime systolic BP had a similar prognostic impact in adult and old women, whereas daytime BP was a stronger predictor of risk in adult men and nighttime BP was a stronger predictor of risk in old men.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no specific funding in relation to this research and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Francesca Coccina wrote the paper, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version. Anna M. Pierdomenico performed statistical analysis, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version. Jacopo Pizzicannella collected the data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version. Umberto Ianni collected the data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version. Gabriella Bufano collected the data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version. Rosalinda Madonna designed the study, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version. Oriana Trubiani designed the study, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version. Francesco Cipollone designed the study, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version. Sante D. Pierdomenico collected the data, designed the study, contributed to the writing of the paper, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and of the revised version.

Coccina F, Pierdomenico AM, Pizzicannella J, et al. Prognostic value of daytime and nighttime blood pressure in treated hypertensive patients according to age and sex. J Clin Hypertens. 2020;22:2014–2021. 10.1111/jch.14028

REFERENCES

- 1. Verdecchia P, Porcellati C, Schillaci G, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure. An independent predictor of prognosis in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1994;24:793‐801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kario K, Pickering TG, Matsuo T, Hoshide S, Schwartz JE, Shimada K. Stroke prognosis and abnormal nocturnal blood pressure falls in older hypertensives. Hypertension. 2001;38:852‐857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bastos JM, Bertoquini S, Polónia J. Prognostic value of subdivisions of nighttime blood pressure fall in hypertensives followed up for 8.2 years. Does nondipping classification need to be redefined? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:508‐515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salles GF, Reboldi G, Fagard RH, et al. Prognostic impact of the nocturnal blood pressure fall in hypertensive patients: the ambulatory blood pressure collaboration in patients with hypertension (ABC‐H) meta‐analysis. Hypertension. 2016;67:693‐700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, et al. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation. 2003;107:1401‐1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turak O, Afsar B, Ozcan F, et al. Relationship between elevated morning blood pressure surge, uric acid, and cardiovascular outcomes in hypertensive patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:530‐535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, et al. Prognostic value of the morning blood pressure surge in 5645 subjects from 8 populations. Hypertension. 2010;55:1040‐1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pierdomenico SD, Di Nicola M, Esposito AL, et al. Prognostic value of different indices of blood pressure variability in hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:842‐847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pierdomenico SD, Cuccurullo F. Prognostic value of white‐coat and masked hypertension diagnosed by ambulatory monitoring in initially untreated subjects: an updated meta‐analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:52‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pierdomenico SD, Pierdomenico AM, Coccina F, et al. Prognostic value of masked uncontrolled hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;72:862‐869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khattar RS, Swales JD, Banfield A, Dore C, Senior R, Lahiri A. Prediction of coronary and cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality by direct continuous ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1999;100:1071‐1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Staessen JA, Thijs L, Fagard R, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk using conventional vs ambulatory blood pressure in older patients with systolic hypertension. JAMA. 1999;282(6):539‐546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khattar RS, Swales JD, Dore C, Senior R, Lahiri A. Effect of aging on the prognostic significance of ambulatory systolic, diastolic, and pulse pressure in essential hypertension. Circulation. 2001;104:783‐789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clement DL, De Buyzere ML, De Bacquer DA, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory blood‐pressure recordings in patients with treated hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2407‐2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dolan E, Stanton A, Thijs L, et al. Superiority of ambulatory over clinic blood pressure measurement in predicting mortality: the Dublin outcome study. Hypertension. 2005;46:156‐161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ben‐Dov IZ, Kark JD, Ben‐Ishay D, Mekler J, Ben‐Arie L, Bursztyn M. Predictors of all‐cause mortality in clinical ambulatory monitoring: unique aspects of blood pressure during sleep. Hypertension. 2007;49:1235‐1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eguchi K, Pickering TG, Hoshide S, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure is a better marker than clinic blood pressure in predicting cardiovascular events in patients with/without type 2 diabetes. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:443‐450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fagard RH, Celis H, Thijs L, et al. Daytime and nighttime blood pressure as predictors of death and cause‐specific cardiovascular events in hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51:55‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dolan E, Stanton AV, Thom S, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring predicts cardiovascular events in treated hypertensive patients‐an Anglo‐Scandinavian cardiac outcomes trial substudy. J Hypertens. 2009;27:876‐885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hansen TW, Li Y, Boggia J, Thijs L, Richart T, Staessen JA. Predictive role of the nighttime blood pressure. Hypertension. 2011;57:3‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roush GC, Fagard RH, Salles GF, et al. Prognostic impact from clinic, daytime, and night‐time systolic blood pressure in nine cohorts of 13,844 patients with hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:2332‐2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow‐up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation. 2005;111:1777‐1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang WY, Melgarejo JD, Thijs L, et al. Association of Office and Ambulatory Blood Pressure With Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes. JAMA. 2019;322:409‐420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de la Sierra A, Redon J, Banegas JR, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with circadian blood pressure patterns in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;53:466‐472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deng M, Chen DW, Dong YF, et al. Independent association between age and circadian systolic blood pressure patterns in adults with hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:948‐955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roush GC, Fagard RH, Salles GF, et al. Prognostic impact of sex‐ambulatory blood pressure interactions in 10 cohorts of 17 312 patients diagnosed with hypertension: systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Hypertens. 2015;33:212‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boggia J, Thijs L, Hansen TW, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in 9357 subjects from 11 populations highlights missed opportunities for cardiovascular prevention in women. Hypertension. 2011;57:397‐405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pierdomenico SD, Lapenna D, Guglielmi MD, et al. Target organ status and serum lipids in patients with white coat hypertension. Hypertension. 1995;26:801‐807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O’Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, et al. European Society of Hypertension Position Paper on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1731‐1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440‐1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Simone G, Devereux RB, Daniels SR, Koren MJ, Meyer RA, Laragh JH. Effect of growth on variability of left ventricular mass: assessment of allometric signals in adults and children and their capacity to predict cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1056‐1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pierdomenico SD, Pierdomenico AM, Cuccurullo F. Morning blood pressure surge, dipping, and risk of ischemic stroke in elderly patients treated for hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:564‐570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pierdomenico SD, Pierdomenico AM, Di Tommaso R, et al. Morning blood pressure surge, dipping, and risk of coronary events in elderly treated hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:39‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pierdomenico SD, Pierdomenico AM, Coccina F, Lapenna D, Porreca E. Circadian blood pressure changes and cardiovascular risk in elderly‐treated hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:805‐811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coccina F, Pierdomenico AM, Cuccurullo C, et al. Prognostic value of morning surge of blood pressure in middle‐aged treated hypertensive patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019;21:904‐910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pickering TG. Reflections in hypertension: work and blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004;6:403‐405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gilbert‐Ouimet M, Trudel X, Brisson C, Milot A, Vézina M. Adverse effects of psychosocial work factors on blood pressure: systematic review of studies on demand‐control‐support and effort‐reward imbalance models. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40:109‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schnall PL, Schwartz JE, Landsbergis PA, Warren K, Pickering TG. Relation between job strain, alcohol, and ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension. 1992;19:488‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, et al. Cigarette smoking, ambulatory blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1995;13:1209‐1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ohta Y, Kawano Y, Hayashi S, Iwashima Y, Yoshihara F, Nakamura S. Effects of Cigarette Smoking on Ambulatory Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, and Heart Rate Variability in Treated Hypertensive Patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2016;38:510‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kario K. Nocturnal hypertension: new technology and evidence. Hypertension. 2018;71:997‐1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heinzer R, Vat S, Marques‐Vidal P, et al. Prevalence of sleep‐disordered breathing in the general population: the HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:310‐318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tikkinen KA, Tammela TL, Huhtala H, Auvinen A. Is nocturia equally common among men and women? A population based study in Finland. J Urol. 2006;175:596‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]