Abstract

Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) has been used to predict adverse outcomes in different clinical settings. This meta‐analysis aimed to compare the prognostic value of different electrocardiographic criteria of LVH at baseline in hypertensive patients. A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed and Embase databases until December 3, 2019. Cohort studies that reported the association of baseline electrocardiographic LVH (Sokolow‐Lyon voltage, Cornell voltage or Cornell product) with all‐cause mortality or major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients were included. The prognostic value of LVH was expressed by the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Nine studies involving 41 870 hypertensive patients were identified. Comparison with those with and without LVH patients indicated that the pooled RR value of all‐cause mortality was 1.30 (95% CI 1.01‐1.66) for the Sokolow‐Lyon voltage criteria, 1.33 (95% CI 1.20‐1.47) for the Cornell voltage criteria, and 1.31 (95% CI 0.97‐1.78) for the Cornell product criteria. In addition, the pooled RR of major cardiovascular events was 1.53 (95% CI 1.27‐1.86) for the Sokolow‐Lyon criteria and 1.46 (95% CI 1.22‐1.76) for the Cornell voltage criteria, respectively. This meta‐analysis suggests that different electrocardiographic criteria for detecting LVH at baseline differ in prediction of all‐cause mortality in patients with hypertension. LVH detected by the Cornell voltage and Sokolow‐Lyon criteria can independently predict the major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients.

Keywords: all‐cause mortality, hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, major adverse cardiac events, meta‐analysis

1. INTRODUCTION

Hypertension, a major modifiable risk factor, is associated with the development of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, vascular disease, and chronic kidney disease. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is highly prevalent in the hypertensive patients. The prevalence of LVH ranged from 36% to 41% in patients with hypertension.1 LVH is identified as a predictor of target organ damage in hypertensive patients.2 Hypertensive patients with LVH are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.3 Conversely, regression of LVH confers a less risk of cardiovascular events in these patients.4

Electrocardiogram is conventionally used for detecting LVH.5 The Sokolow‐Lyon, Cornell voltage, and Cornell product are the most frequently applied the electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of LVH.6 Several studies7, 8, 9, 10, 11 have been reported that electrocardiographic LVH could help clinicians to improve risk stratification of hypertensive patients. However, the prognostic values of LVH determined by different electrocardiographic criteria are controversial in this specific population.12 No previous meta‐analysis has been compared the prognostic utility of different electrocardiographic criteria of LVH in patients with hypertension. The aim of this meta‐analysis was to compare the prognostic value of baseline LVH detected by the different electrocardiographic criteria in hypertensive patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search for original studies was conducted in PubMed and Embase databases until December 3, 2019. The following search items were used in combination: “left ventricular hypertrophy” AND “electrocardiographic” OR “electrocardiogram” AND “hypertension” AND “follow‐up”. Additionally, we also manually searched the reference lists of pertinent articles to identify any potentially missing studies.

2.2. Study selection

Eligible studies had to satisfy all the following inclusion criteria: (a) observational studies that enrolled the hypertensive patients; (b)baseline LVH detected by the electrocardiographic criteria (Sokolow‐Lyon voltage, Cornell voltage or Cornell product); (c) major cardiovascular events (defined as cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, revascularization, peripheral arterial disease, etc) or all‐cause mortality as outcome measures; and (d) provided adjusted hazard ratio (HR) or risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) of outcomes associated with the electrocardiographic LVH. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) electrocardiographic LVH as a continuous variable; (b) reported unadjusted risk estimate; (c) participants from the general population or other specific diseases; (d) studies not using electrocardiographic LVH as exposure; and (e) co‐presence of other morbidities.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently recorded the following information: first author's last name, year of publication, study design, geographic region of study, number of patients, sex, age at baseline, definition of LVH, outcome measures, length of follow‐up, fully adjusted risk estimate, and adjustment for covariates. The methodological quality of the eligible studies was blindly examined by two reviewers using a 9‐point Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort study.13 Study with a rating of seven points or over was considered as high quality. Discrepancies in data extraction and quality assessment were solved by a third author.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using Stata 12.0 (Stata Corporation). The prognostic value of LVH was expressed by the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for those with and without LVH patients. Heterogeneity between studies was determined using the I2 statistics and Cochrane Q test. Significant heterogeneity was deemed as a significance level of P < .10 of Cochrane Q test or I2 statistics >75%. We selected a random effect model when the statistical heterogeneity was observed. Otherwise, a fixed‐effect model was applied. To observe the robustness of the pooled risk summary, sensitivity analysis excluding one study at a time was conducted. When more than 10 studies were included in the analysis, Begg's test14 and Egger's test15 were used to check publication bias.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results and studies' characteristics

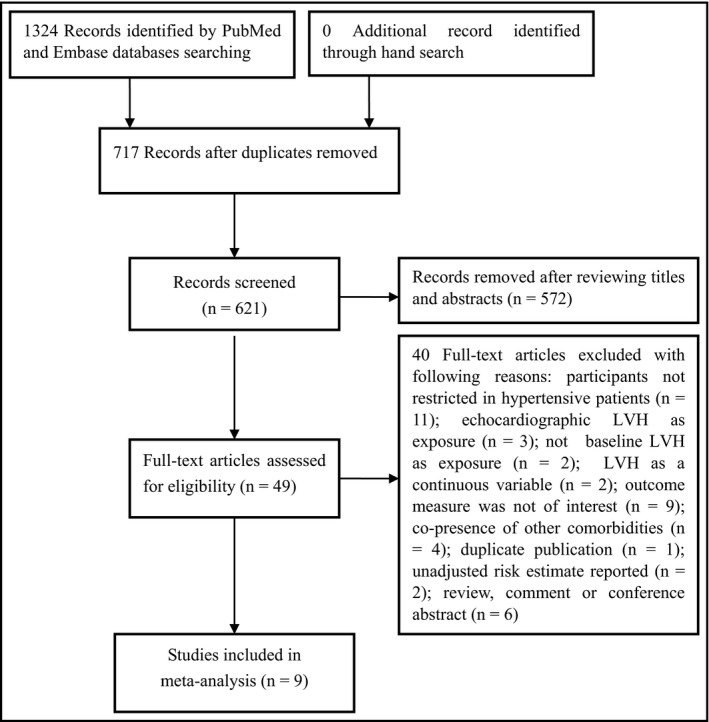

A flowchart showing the studies selection process is shown in Figure 1. After removed duplicates, a total of 621 potentially relevant records were identified from our literature search. After scanning the titles or abstracts, 572 records were excluded due to obviously irrelevant. We retrieved 49 full‐text articles for further assessment. Of which, 40 articles were removed for various reasons. Thus, nine studies7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18 involving 41 870 hypertensive patients satisfied our inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of studies selection process

The main characteristics of eligible studies are presented in Table 1. Two studies10, 17 were designed as retrospective, and others were prospective designs. These studies were published from 1998 to 2019. The study sample size differed from 284 to 26,384 patients. The mean age of patients ranged from 44.1 to 83.5 years old. The length of follow‐up differed from 2.0 years to 16 years. Table 2 summarizes the demographic characteristic of the included studies. For methodological quality, six studies were graded as high methodological quality.

Table 1.

Main characteristic of the included studies

| Author/year | Country | Study design | Sample size | MACE definition |

Outcome measures RR/HR (95% CI) |

Follow‐up (years) | Adjustment for covariates | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verdecchia 199816 | Italy | Prospective | 1717 | MI or angina, stroke, TIA, aortoiliac occlusive disease, retinal artery occlusion, CHF hospitalization, or renal failure requiring dialysis |

MACE:159 1.19 (0.77‐1.83) SL; 1.34 (0.86 −2.08) CV |

3.3 | Age, sex, DM, clinical blood pressure, ambulatory blood pressure, TC, smoking, BMI, antihypertensive therapy | 7 |

| Li 20087 | China | Prospective | 2240 | Cardiovascular death, MI, sudden death, stroke |

MACE:158; 1.65 (1.19‐2.28) SL; Total death:105 1.70 (1.08‐2.69) SL |

15 | Age, sex, smoking, BMI, TC, education, use of antihypertensive drugs, | 7 |

| Salles 201012 | Brazil | Prospective | 552 | Deaths, new‐onset HF, stroke, myocardial, aortic or lower limb revascularization |

MACE:109; 1.22 (0.78‐1.92) SL; 1.32 (0.85‐2.05) CV; 1.52 (1.01‐2.30) CP; Total death:70 1.02 (0.57‐1.83) SL; 1.86 (1.08‐3.18) CV; 1.77 (1.06‐2.94) CP |

4.8 | Age, sex, BMI, DM, current smoking, dyslipidemia, previous CVD, creatinine, number of antihypertensive drugs, 24‐hour SBP, non‐dipping pattern on ambulatory blood pressure | 6 |

| Jissho 20108 | Japan | Prospective | 3230 | Stroke, CVD, and renal failure |

MACE:164 1.92 (1.35‐ 2.73) SL |

2.0 | Age, sex, obesity, treatment group, SBP, DBP, smoking, DM, dyslipidemia, history of heart disease, renal disease, or stroke. | 7 |

| Vinyoles 20159 | Spain | Prospective | 352 | Cardiovascular death, MI, stable angina, HF, stroke, TIA, revascularizations |

MACE:62 2.66 (1.39‐ 5.10) CV |

16 | Age, sex, SBP, DM, smoking | 6 |

| Antikainen 201617 | Multi‐nation | Retrospective | 3034 | ‐ |

Total death:192 1.08 (0.74‐1.56) SL 1.16(0.81‐1.64) CV 1.11(0.76‐1.62) CP |

2.1 | Age, sex, DBP, heart rate, race, smoking, DM, previous CVD, intervention, UA | 7 |

| Bang 201710 | Muiti‐nation | Retrospective | 26 384 | CHD, nonfatal MI, stroke, angina, HF, and PAD |

Total death:3561 1.30(1.15‐1.47) CV |

6.0 | Age, treatment group, race, ethnicity, DM, CHD, smoking, aspirin use, heart rate, BMI, SBP, potassium, glucose, eGFR, TC, LDL, HDL, TG | 8 |

| Ahmad 201911 | USA | Prospective | 4077 | ‐ |

Total death:1506 1.43 (1.13‐1.82) CV |

14 | Age, sex, race, DM, smoking, hyperlipidemia, obesity, abnormal deep terminal negativity of P wave in V1. | 8 |

| Chen 201918 | China | Prospective | 284 | ‐ |

Total death:35 2.31 (0.93‐5.72) SL |

2.3 | Age, sex, BMI, smoking, CVD, antihypertensive drugs, fasting glucose, TC, UA, SBP, eGFR, MMSE score, heart rate | 6 |

Common electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy criteria: (a) Sokolow‐Lyon; (b) Cornell product; and (c) Cornell voltage.

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence intervals; CP, Cornell product; CV, Cornell voltage; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NOS, Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; RR, risk ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SL, Sokolow‐Lyon; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; UA, uric acid.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristic of the included studies

| Study/year | Age (years) | Men (%) | BMI (kg/m2) | Diabetes (%) | Dyslipidemia (%) | Smokers (%) | Baseline SBP (mm Hg) | Baseline DBP (mm Hg) | Anti‐HTN treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verdecchia 199816 | 52 ± 12 | 51 | 26.8 ± 4 | 8 | NP | 23 | 157 ± 19 | 97 ± 10 | 32 |

| Li 20087 | 61.7 ± 8.9 | 50 | 25.4 ± 3.6 | NP | NP | 30 | 151 ± 20.3 | 93 ± 10 | NP |

| Salles 201012 | 65.8 ± 11.2 | 28.8 | 30 ± 5.9 | 36.3 | 86.8 | 8.1 | 178 ± 27.6 | 98.8 ± 18.5 | NP |

| Jissho 20108 | 73.5 ± 5.2 | 38.2 | 23.6 ± 3.4 | 11.9 | 52.6 | 13.1 | 171 ± 9.4 | 88.8 ± 9.1 | 50.7 |

| Vinyoles 20159 | 44.1 ± 7.9 | 41.8 | NP | NP | 46.5 | 27.8 | 142.7 ± 15.3 | 89.3 ± 9.6 | 63.3 |

| Antikainen 201617 | 83.5 ± 3.1 | 37.9 | 24.8 ± 3.7 | 7.6 | NP | 6.8 | 173 ± 8.5 | 91.1 ± 8.3 | 64.7 |

| Bang 201710 | 66.7 ± 7.6 | 53.7 | 29.7 ± 6.1 | 35.1 | NP | 22.2 | 146 ± 16 | 84 ± 10 | NP |

| Ahmad 201911 | 61.2 ± 12.3 | 48.8 | NP | 12.8 | NP | 53.2 | 141.6 ± 17.2 | 80.1 ± 10.2 | 32.5 |

| Chen 201918 | 83(81‐85) | 26.1 | 22.5 (21‐24) | NP | NP | 7.7 | 175 (165‐186) | 85 (78‐92) | 48.9 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HTN, hypertension; NP, not provided.

3.2. All‐cause mortality

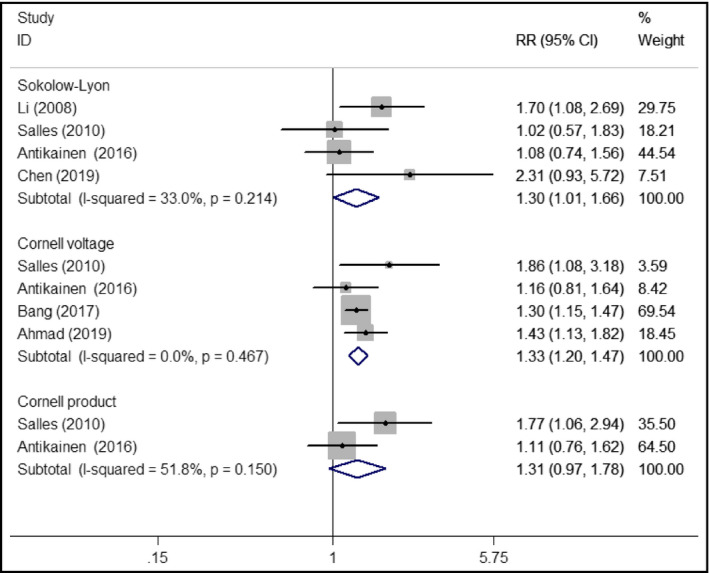

Six studies7, 10, 11, 12, 17, 18 reported the association between electrocardiographic LVH and all‐cause mortality. Comparison with those with and without LVH patients (Figure 2), the pooled RR was 1.30 (95% CI 1.01‐1.66; I2 = 33.0%; P = .214) for Sokolow‐Lyon voltage criteria,7, 12, 17 1.33 (95% CI 1.20‐1.47; I2 = 0.0%; P = .467) for Cornell voltage criteria10, 11, 12, 17 and 1.31 (95% CI 0.97‐1.78; I2 = 51.8%; P = .150) for Cornell product criteria.12, 17 In the sensitivity analyses, the pooled RR after removing one study at a time ranged from 1.15 to 1.50 and the low 95% CI ranged from 0.86 to 1.07 for Sokolow‐Lyon voltage.

Figure 2.

Forest plots showing pooled RR with 95% CI of all‐cause mortality for electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy

3.3. Major adverse cardiac events

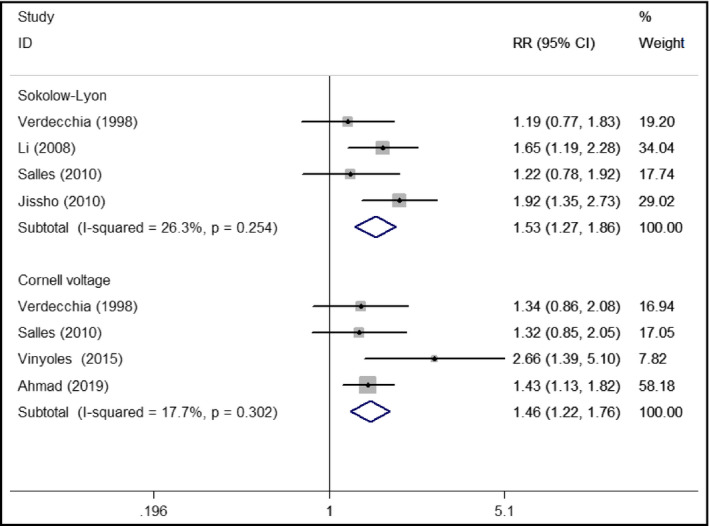

Five studies7, 8, 9, 12, 16 reported the association between electrocardiographic LVH and major adverse cardiovascular events. Comparison with those with and without LVH patients (Figure 3), the pooled RR was 1.53 (95% CI 1.27‐1.86; I2 = 26.3%; P = .254) for Sokolow‐Lyon voltage criteria7, 8, 12, 16 and 1.46 (95% CI 1.22‐1.76; I2 = 17.7%; P = .302) for Cornell voltage criteria.9, 12, 16 The pooled RR after removing one study at a time ranged from 1.40 to 1.63 for Sokolow‐Lyon voltage and 1.39‐1.51 for Cornell voltage.

Figure 3.

Forest plots showing pooled RR with 95% CI of major adverse cardiac events for electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy

3.4. Publication bias

As for the analyzed outcomes enrolled less than the recommended arbitrary minimum number of 10 studies, we did not conduct the publication bias test because the results of these statistical tests were potentially unreliable under such condition.19

4. DISCUSSION

This meta‐analysis indicates that baseline electrocardiographic LVH detected by Cornell voltage independently predicts all‐cause mortality and major cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension. Hypertensive patients with electrocardiographic LVH‐Cornell voltage exhibited a 33% high risk of all‐cause mortality and 46% higher risk of major cardiovascular events. In addition, hypertensive patients with electrocardiographic LVH‐Sokolow‐Lyon voltage had a 53% high risk of major cardiovascular events. However, electrocardiographic LVH detected by Cornell product appeared to not predict all‐cause mortality in patients with hypertension.

Previous meta‐analyses have confirmed that regression of LVH significantly reduced cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension.20 Despite regression is associated with an improvement in cardiovascular outcomes, it remains increased than those never suffered LVH.21 Concomitant presence of LVH and other morbidities such as coronary artery disease or chronic kidney disease carried more risk of cardiovascular events.22, 23 Our meta‐analysis only focused on the prognostic utility of baseline electrocardiographic LVH in hypertensive patients. Our meta‐analysis supported an increased risk of major cardiovascular events and all‐cause mortality among hypertensive patients with electrocardiographic LVH. Increased major cardiovascular events were observed for both Sokolow‐Lyon and Cornell voltage criteria, although the risk estimate was higher for the former criteria. However, prediction of all‐cause mortality associated with LVH was observed in Cornell voltage and Sokolow‐Lyon voltage but not in Cornell product criteria. It should be noted that the values of Sokolow‐Lyon voltage for predicting all‐cause mortality was reliable in the sensitivity analyses. On the basis of the current findings, LVH assessment is recommended using Cornell voltage criteria in the clinical setting for hypertensive patients.

Electrocardiogram has the advantages of easy availability and low cost in detecting LVH. The guidelines of European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology recommend the use of the Sokolow‐Lyons or Cornell voltage of the electrocardiogram for diagnosis of LVH.24 LVH may alter electrocardiographic pattern either by increasing QRS voltage and duration. Among the various QRS voltages, the Cornell voltage had the closest association with left ventricular mass and therefore its diagnostic performance was superior to the Sokolow‐Lyon voltage under a receiver operator characteristic curve analysis.25 The Sokolow‐Lyon voltage is considered less sensitive than other electrocardiographic criteria in detection of LVH.26 The Cornell voltage derives from the vectorcardiographic abnormalities and may be less affected by the distance from the myocardium to electrodes.

This meta‐analysis should be interpreted with several potential limitations. First, electrocardiographic criteria for LVH are less sensitivity than other diagnostic techniques such as echocardiography, magnetic resonance or computerized tomography, which may have led to underestimate the effect of LVH on adverse outcomes. The included studies did not clearly report or provide the echocardiographic data of the patients. Nevertheless, whether LVH criteria in the electrocardiogram are supported by the echocardiograph is unclear. Second, there were sex and ethnic differences on electrocardiographic diagnosed LVH.27, 28 We failed to conduct the subgroup analysis according to these characteristics due to insufficient such data. Finally, confounding factors such as antihypertensive treatment and time‐varying blood pressure were not adjusted in all the analyzed studies. Antihypertensive agents may attenuate LVH and subsequently reduce cardiovascular events.29 Therefore, our pooled risk estimate may have underestimated the actual risk. Finally, we only analyzed the most widely used electrocardiographic LVH criteria and did not investigate the other criteria.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This meta‐analysis indicates that different electrocardiographic criteria for detecting LVH at baseline differ in prediction of all‐cause mortality in patients with hypertension. LVH detected by the Cornell voltage and Sokolow‐Lyon criteria can independently predict the major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients. Monitoring electrocardiographic LVH may play an important role in treatment evaluation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

XQ Wei contributed to study conceptualization, project administration, and revising and editing; HS Zhang and LA Hu contributed to literature search, data extraction, and formal analysis; and HS Zhang contributed to draft manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Zhang H, Hu L, Wei X. Prognostic value of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients: A meta‐analysis of electrocardiographic studies. J Clin Hypertens. 2020;22:254–260. 10.1111/jch.13795

Funding information

This work was supported by the Development Plan of TCM Science and Technology in Shandong (2019‐0487).

REFERENCES

- 1. Cuspidi C, Rescaldani M, Sala C, et al. Prevalence of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in human hypertension: an updated review. J Hypertens. 2012;30:2066‐2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kahan T. The importance of left ventricular hypertrophy in human hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl. 1998;16:S23‐S29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rautaharju PM, Soliman EZ. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events: a critical appraisal. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47:649‐654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bang CN, Devereux RB, Okin PM. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy or strain is associated with lower incidence of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients independent of blood pressure reduction ‐ A LIFE review. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47:630‐635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schillaci G, Battista F, Pucci G. A review of the role of electrocardiography in the diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45:617‐623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pewsner D, Juni P, Egger M, et al. Accuracy of electrocardiography in diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in arterial hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2007;335:711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li Y, Zhao D, Liu J, et al. Association between hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiovascular events in adult Beijing residents: a cohort study. Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi. 2008;36:1037‐1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jissho S, Shimada K, Taguchi H, et al. Impact of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy on the occurrence of cardiovascular events in elderly hypertensive patients. ‐ The Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients. Circ J. 2010;74:938‐945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vinyoles E, Soldevila N, Torras J, et al. Prognostic value of non‐specific ST‐T changes and left ventricular hypertrophy electrocardiographic criteria in hypertensive patients: 16‐year follow‐up results from the MINACOR cohort. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bang CN, Soliman EZ, Simpson LM, et al. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy predicts cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients: the ALLHAT study. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:914‐922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ahmad MI, Mujtaba M, Anees MA, et al. Interrelation between electrocardiographic left atrial abnormality, left ventricular hypertrophy, and mortality in participants with hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124(6):886‐891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salles GF, Cardoso CR, Fiszman R, et al. Prognostic impact of baseline and serial changes in electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in resistant hypertension. Am Heart J. 2010;159:833‐840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The newcastle‐ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta‐analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp Assessed August 6, 2019.

- 14. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088‐1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629‐634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, et al. Prognostic value of a new electrocardiographic method for diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:383‐390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Antikainen RL, Peters R, Beckett NS, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy is a predictor of cardiovascular events in elderly hypertensive patients: hypertension in the very elderly trial. J Hypertens. 2016;34:2280‐2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen R, Bai K, Lu F, et al. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and mortality in an oldest‐old hypertensive Chinese population. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1657‐1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, et al. The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ. 2006;333:597‐600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Costanzo P, Savarese G, Rosano G, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy reduction and clinical events. A meta‐regression analysis of 14 studies in 12 809 hypertensive patients. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2757‐2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Angeli F, Reboldi G, Poltronieri C, et al. The prognostic legacy of left ventricular hypertrophy: cumulative evidence after the MAVI study. J Hypertens. 2015;33:2322‐2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paoletti E, De Nicola L, Gabbai FB, et al. Associations of left ventricular hypertrophy and geometry with adverse outcomes in patients with CKD and hypertension. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:271‐279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim YH, Her AY, Choi BG, et al. Impact of left ventricular hypertrophy on long‐term clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients who underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention with drug‐eluting stents. Medicine. 2018;97:e12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European society of hypertension (ESH) and of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462‐1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schillaci G, Verdecchia P, Borgioni C, et al. Improved electrocardiographic diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:714‐719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Norman JE Jr, Levy D. Improved electrocardiographic detection of echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy: results of a correlated data base approach. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1022‐1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Antikainen RL, Grodzicki T, Palmer AJ, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy determined by Sokolow‐Lyon criteria: a different predictor in women than in men? J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:451‐459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vinyoles E, Rodriguez‐Blanco T, de la Figuera M, et al. Variability and concordance of cornell and Sokolow‐Lyon electrocardiographic criteria in hypertensive patients. Blood Press. 2012;21:352‐359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Milan A, Caserta MA, Avenatti E, et al. Anti‐hypertensive drugs and left ventricular hypertrophy: a clinical update. Intern Emerg Med. 2010;5:469‐479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]