Abstract

Elevated morning blood pressure (BP) has a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events, so morning BP is of substantial clinical importance for the management of hypertension. This study aimed to evaluate early morning BP control and its determines among treated patients with controlled office BP. From May to October 2018, 600 treated patients with office BP < 140/90 mm Hg were recruited from hypertension clinics. Morning BP was measured at home for 7 days. Morning home systolic blood pressure (SBP) increased by an average of 11.5 mm Hg and that morning home diastolic blood pressure (DBP) increased by an average of 5.6 mm Hg compared with office BP. Morning home SBP, DBP, and their moving average were more likely to be lower among patients with a office SBP < 120 mm Hg than among patients with a office SBP ranging from 120 to 129 mm Hg and from 130 to 139 mm Hg (P < .001). A total of 45% of patients had early morning BP < 135/85 mm Hg. The following factors were significantly correlated with morning BP control: male sex, age of <65 years, absence of habitual snoring, no drinking, adequate physical activity, no habit of high salt intake, office BP < 120/80 mm Hg, and combination of a calcium channel blocker (CCB) and angiotensin receptor blocker or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ARB/ACEI). Less than half of patients with controlled office BP had controlled morning BP and that positive changes may be related to an office BP < 120/80 mm Hg, combination of a CCB and ACEI/ARB and a series of lifestyle adjustments.

Keywords: blood pressure control, hypertension, morning blood pressure, office blood pressure

1. INTRODUCTION

The latest study (PURE) showed that hypertension was the largest risk factor, and 22.3% of cardiovascular disease (CVD) cases and deaths were attributed to hypertension.1 So health policies focus on hypertension control which has the greatest effect on averting CVD and death. Office BP remains the reference standard for BP assessment, but cardiovascular risk assessment using office BP control alone are inadequate for predicting CVD in patients with hypertension because people undergo treatment and have controlled office BP are more likely to develop CVD than those without hypertension.2 While only half of patients with controlled office BP had a controlled morning BP.3, 4

Recent studies have shown that the morning BP rise was a strong predictor of CVD. Stroke and coronary artery events are 70% more common from 07:00 to 09:00 than at other times.5 Regardless of the office blood pressure (BP) level, patients with morning BP rise have a significantly increased risk of CVD events.6, 7 A cohort study showed that a 1 mm Hg morning BP increase was associated with a 2.1% increased risk of cardiovascular death.8 The Japan Morning Surge Home Blood Pressure study also indicated that patients with uncontrolled morning BP had a higher risk of stroke (within the systolic blood pressure [SBP] range of 135‐144 mm Hg: hazard ratio [HR] of 2.45; SBP of 145‐154 mm Hg: HR of 2.8; SBP of 155‐164 mm Hg: HR of 3.58; and SBP of ≥165 mm Hg: HR of 6.52) than those with controlled morning BP at home.9

Office BP combined with early morning BP may be superior to office BP in predicting cardiovascular risk. In the HONEST study, cardiovascular risk was higher in patients with morning BP > 145 mm Hg and office BP < 130 mm Hg (HR, 2.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20‐5.08) than in patients with morning home BP < 125 mm Hg and office BP < 130 mm Hg.10 Based on strong evidence,3, 4, 11, 12, 13 hypertension guidelines14, 15, 16 support morning BP assessment among patients with hypertension.

Now, hypertension is a serious public health problem with a prevalence of 23.2% (≈244.5 million) of the Chinese adult population ≥18 years of age.17 BP lowering is beneficial and is associated with CVD control.18 But most of doctors focus on office BP control, and morning home BP was seldom assessed among patients with hypertension. Therefore, we conducted this study to discover the problems of morning BP control and provided clues for the further study.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants

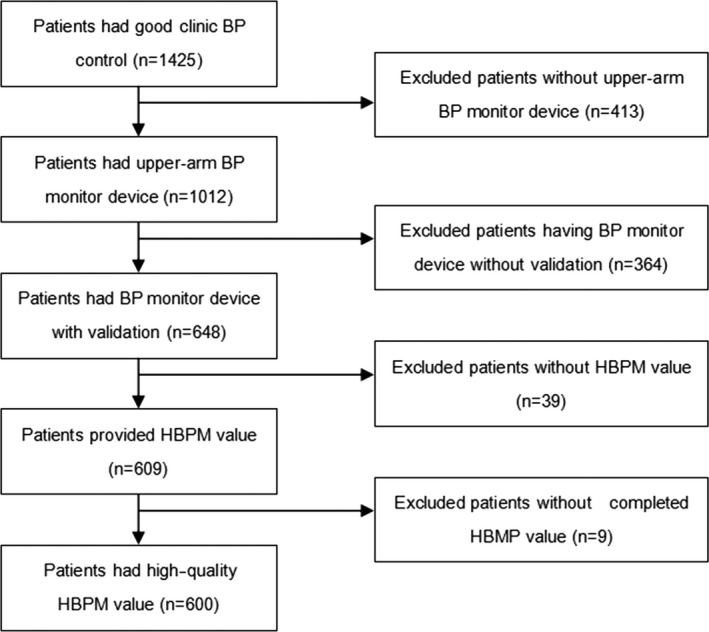

This cross‐sectional survey was conducted from May to October 2018. We prospectively recruited patients with hypertension who visited hypertension clinics from 13:00 to 16:00 and had controlled office BP in Anzhen Hospital, Beijing, China. All patients were asked to duplicate early morning self‐measurements for 7 days and record the BP readings. The inclusion criteria were (a) an age of 35‐70 years, (b) treatment with antihypertensive medications for a minimum of 3 months and completely followed the regime (dosage, timing, route of administration) in the past 2 weeks, (c) at least four recorded visits in the electronic medical records, and (d) had an upper‐arm medical electronic sphygmomanometer in the patient's home. The exclusion criteria were (a) irregular intake of antihypertensive drugs; (b) frequent day and night working shifts; (c) stroke, coronary heart disease, serious congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency requiring dialysis treatment, and/or cancer; (d) upper‐arm medical electronic sphygmomanometer, which has not been validated by international standardized protocols (the British Hypertension Society, European Society of Hypertension, or Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation). All patients provided written informed consent. A total of 1425 patients met the selection criteria, 825 patients were excluded, and the reasons were as follows: without upper‐arm BP monitor device (n = 413); upper‐arm medical electronic sphygmomanometer, which has not been validated (n = 364); without home BP monitoring (HBPM) value (n = 39); patients without completed HBMP value (n = 9). At last 600 patients were enrolled in the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart. BP, blood pressure; HBPM, home blood pressure monitoring

2.2. Check of the individual's BP measuring device

Morning home BP assessment was achieved by HBPM according to hypertension guideline.14, 16 Every participant was requested to provide the brand of the device, some brands which had electronic sphygmomanometer certification were popular in China, such as “Microlife,” “Maibobo,” “Omron,” “Yuwell,” and “Andon.” If participants could not provide the brand, they were asked to bring the device to clinic, and doctors would check it at the following website: http://www.dableducational.org, or http://www.bhsoc.org/default.stm.

2.3. Data collection

The patients’ demographic information, medical history, and lifestyle details were collected by trained research staff using a standard questionnaire. Height, weight, and BP were measured in the office. Office BP was measured using a standard and validated upper‐arm medical electronic sphygmomanometer cuff placed on the right arm, supported at the level of the heart. The participants rested for at least 5 minutes in a seated position. Two BP measurements should be taken 1‐2 minutes apart and averaged for records. An additional measurement is required if the first two readings differ by >5 mm Hg, and the mean value of the three readings should be recorded.19

Early morning BP was defined as a BP measurement within 1 hour after waking and before drug and breakfast intake. So early morning BP was measured within 1 hour of waking, from 06:00 to 10:00, after urination but before drug intake and breakfast using a validated upper‐arm medical electronic sphygmomanometer in the morning for seven consecutive days.14, 15, 16 Two BP measurements should be taken 1‐2 minutes apart and averaged for records. An additional measurement is required if the first two readings differ by >5 mm Hg, and the mean value of the three readings should be recorded. Home BP data were collected through a unified form; each participant was trained to correctly fill in the form. The average BP for 6 days after discarding measurements on the first day was calculated as the early morning BP.19, 20

2.4. Definitions and diagnostic criteria

Uncontrolled office BP was defined as SBP of ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of ≥90 mm Hg, controlled office BP was defined as SBP of <140 mm Hg and DBP of <90 mm Hg,20 and early morning BP control was defined as early morning BP < 135/85 mm Hg.14 Current smokers were defined as those who smoked >1 cigarette per day, and nonsmokers were defined as those who had stopped smoking within the previous 12 months, had never smoked, or smoked <1 cigarette per day. Passive smoking was defined as nonsmokers who are exposed to smoke exhaled by smokers at least 1 day a week for 15 minutes. Current drinking was defined as alcohol intake of more than once per week during the previous 12 months. For adult males, alcohol drinking was defined as daily drinking beer over 750 mL, wine over 250 mL, or 38‐degree alcoholic liquor over 75 g. For adult females, these quantities were 450 mL, 150 mL, and 50 g respectively. Adequate physical activity was defined as exercise performed at least 5 days a week for >30 minutes (total time of ≥150 min/wk). The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body mass in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. An overweight status was defined as a BMI of 24.0 to 27.9 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as a BMI of ≥28.0 kg/m2. The combination of a calcium channel blocker (CCB) and angiotensin receptor blocker or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ARB/ACEI) was defined as combination therapy of two or more drugs as follows: CCB + ARB/ACEI, CCB + ARB/ACEI + diuretic, CCB + ARB/ACEI + β‐blocker, or CCB + ARB/ACEI + β‐blocker + diuretic.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows version 18.0 (SPSS Inc). The chi‐square test was used to compare differences in proportions between groups, and one‐way analysis of variance was used to compare differences in mean BP between groups. Multiple backward stepwise logistic regression was performed to identify the factors influencing control of morning BP, and all variables based on the chi‐square test were entered into a multivariate model. Odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated for each independent variable. All reported P‐values were two‐tailed, and P‐values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. General information

In total, 600 patients (male, n = 339; female, n = 261) were enrolled in the study. Their mean age was 57.8 ± 8.2 years, and 324 (54.0%) were younger than 65 years. A total of 27.5% of patients had an office BP of <120/80 mm Hg. No significant differences were identified in the general characteristics between male and female patients with the exception of current drinking and habitual snoring. Table 1 shows the participants’ demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants by sex

| Characteristics | Male | Female | χ2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| <65 | 165 (48.7) | 159 (60.9) | 8.904 | .003 |

| ≥65 | 174 (51.3) | 102 (31.9) | ||

| Obesity | 159 (46.9) | 135 (51.7) | 1.372 | .242 |

| Habitual snore | 213 (62.8) | 120 (46.0) | 16.962 | <.001 |

| Current smoking/ Passive smoking | 140 (41.3) | 112 (42.9) | 0.158 | .691 |

| Current drinking | 72 (21.2) | 21 (8.0) | 19.597 | <.001 |

| Inadequate physical activity | 81 (23.9) | 63 (24.1) | 0.005 | .945 |

| Habit of heavy taste | 243 (71.7) | 183 (70.1) | 0.176 | .675 |

| Diabetes | 90 (26.5) | 60 (23.0) | 0.997 | .318 |

| Clinic BP <120/80 mm Hg | 93 (27.4) | 72 (27.6) | 0.002 | .967 |

Data are presented as n (%).

Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

3.2. Early morning BP level by different office BP levels

Early morning SBP increased by an average of 11.5 mm Hg (range, −14 to 42 mm Hg; standard deviation, 8.2 mm Hg) compared with office BP, and DBP increased by an average of 5.6 mm Hg (range, −6 to 28 mm Hg; standard deviation, 4.3 mm Hg). Early morning SBP, DBP, and the mean difference of SBP between morning BP and office BP were more likely to be lower among patients with office SBP < 120 mm Hg than among patients with office SBP ranging from 120 to 129 mm Hg and from 130 to 139 mm Hg (P < .001), and the early morning BP control rate was significantly higher among patients with office SBP < 120 mm Hg. Similar results were obtained for patients with office DBP < 80 mm Hg and office BP < 120/80 mm Hg (all P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Morning BP level by different clinic BP levels

| Clinic BP level (mm Hg) | Mean difference between morning BP and clinic BP (mm Hg) | Morning blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference of SBP | Mean difference of DBP | Mean SBP | Mean DBP | BP control | |

| SBP (mm Hg) | |||||

| <120 (n = 177) | 7.0 ± 7.8 | 3.9 ± 3.5 | 122.2 ± 7.2 | 78.7 + 8.0 | 138 (78.0) |

| 120‐129 (n = 204) | 10.1 ± 8.7 | 5.8 ± 4.2 | 129.4 ± 3.0 | 81.8 ± 8.2 | 117 (57.4) |

| 130‐139 (n = 219) | 16.5 ± 9.3 | 6.9 ± 4.7 | 144.1 ± 8.4 | 88.4 ± 9.1 | 15 (6.8) |

| DBP (mm Hg) | |||||

| <80 (n = 327) | 8.8 ± 9.7 | 4.5 ± 3.6 | 125.2 ± 10.5 | 74.9 ± 6.2 | 243 (74.3) |

| ≥80 (n = 273) | 14.7 ± 9.7 | 6.9 ± 4.6 | 138.2 ± 11.3 | 91.3 ± 4.5 | 27 (9.9) |

| SBP/DBP (mm Hg) | |||||

| <120/80 (n = 165) | 6.7 ± 8.7 | 3.7 ± 3.0 | 117.1 ± 6.2 | 75.6 ± 7.6 | 108 (65.5) |

| ≥120/80 (n = 435) | 13.5 ± 9.0 | 6.4 ± 4.5 | 133.4 ± 12.8 | 83.8 ± 10.1 | 162 (37.2) |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

3.3. Factors influencing morning BP control

More than 63.0% of patients had early morning SBP control, 54.5% had good DBP control, and 45.0% had SBP and DBP control. Morning BP control was likely to be higher in female patients; patients aged <65 years; patients with no habitual snoring, no drinking, adequate physical activity, no habit of high salt intake, or office BP of <120/80 mm Hg; and patients treated with a combination of CCB + ACEI/ARB (Table 3). The multivariate regression analysis also showed that the above factors were significantly correlated with controlled morning BP as follows: female sex, age of <65 years, no habitual snoring, no drinking, adequate physical activity, no habit of high salt intake, office BP of <120/80 mm Hg, and a combination of CCB + ARB/ACEI.

Table 3.

Factors influencing morning BP control

| Characteristics | Morning BP control | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | DBP | SBP and DBP | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sexb, c | |||||

| Female | 174 (66.7) | 180 (69.0) | 138 (52.9) | 1 | .001 |

| Male | 207 (61.1) | 147 (43.4) | 132 (38.9) | 0.57 (0.36‐0.91) | |

| Agec | |||||

| ≥65 | 180 (65.2) | 138 (50.0) | 108 (39.1) | 1 | .008 |

| <65 | 201 (62.0) | 189 (58.3) | 162 (50.0) | 1.48 (1.03‐2.73) | |

| Obesity | |||||

| Yes | 177 (60.2) | 153 (52.0) | 126 (42.9) | ‐ | |

| No | 204 (66.7) | 174 (56.9) | 144 (47.1) | ‐ | |

| Current smoking/ Passive smoking | |||||

| Yes | 168 (66.7) | 135 (53.6) | 117 (46.4) | ‐ | |

| No | 213 (61.2) | 192 (55.2) | 153 (44.0) | ‐ | |

| Habitual snorea, b, c | |||||

| Yes | 198 (59.5) | 162 (48.6) | 132 (39.6) | 1 | .003 |

| No | 183(68.5) | 177 (66.3) | 138 (51.7) | 1.63 (1.12‐2.83) | |

| Current drinkinga, b, c | |||||

| Yes | 42 (45.2) | 39 (41.9) | 30 (32.3) | 1 | .007 |

| No | 339 (66.9) | 288 (56.8) | 240 (47.3) | 1.89 (1.19‐3.08) | |

| Inadequate physical activityb, c | |||||

| Yes | 87 (60.4) | 66 (45.8) | 54 (37.5) | 1 | .038 |

| No | 294 (64.5) | 261 (57.2) | 216 (47.4) | 1.42 (1.08‐2.81) | |

| Habit of high salt intakeb, c | |||||

| Yes | 264 (62.0) | 213 (50.0) | 177 (44.1) | 1 | .008 |

| No | 117 (67.2) | 114 (65.5) | 93 (53.4) | 1.62 (1.14‐2.96) | |

| Diabetesa, b | |||||

| Yes | 78(52.0) | 69 (46.0) | 60 (40.0) | ‐ | |

| No | 303 (67.3) | 258 (57.3) | 210 (46.7) | ‐ | |

| Clinic BP <120/80 mm Hga, b, c | |||||

| No | 249 (57.2) | 204 (46.9) | 162 (37.2) | 1 | <.001 |

| Yes | 132 (80.0) | 123 (75.4) | 108 (65.5) | 2.93 (1.48‐4.79) | |

| Combination of CCB + ARB/ACEIa, b, c | |||||

| No | 231 (58.3) | 183 (46.2) | 148 (37.4) | 1 | <.001 |

| Yes | 150 (73.5) | 144 (70.6) | 122 (59.8) | 2.38 (1.33‐4.47) | |

Data are presented as n (%).

Abbreviations: ARB/ACEI, angiotensin receptor blocker/angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CI, confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; OR, odds ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Significant difference in morning SBP control between the two groups.

Significant difference in morning DBP control between the two groups.

Significant differences in both morning SBP and DBP control between the two groups.

3.4. Correlation between antihypertensive regimens and office BP

A total of 177 patients (29.5%) treated with monotherapy, 423 treated with combination therapy (two antihypertensive drugs: 275; three antihypertensive drugs: 122; four antihypertensive drugs: 26). Patients treated with CCB, ACEI/ARB, β‐blocker, or diuretic accounted for 64.5% (387/600, 18 patients used intermediate‐acting CCB), 57.8% (347/600), 41.2% (247/600, 32 patients used intermediate‐acting β‐blocker) and 22.0% (216/600), respectively. No short‐acting antihypertensive drugs was taken among all the patients, about 5% (34/600) patients took antihypertensive drugs in the afternoon or at night. A great number of patients (204/600) treated with combination therapy which included CCB and ACEI/ARB (CCB + ACEI/ARB: 106/204; CCB + ACEI/ARB + β‐blocker or diuretic: 72/204; CCB + ACEI/ARB + β‐blocker + diuretic: 26/204). All the other combination therapy accounted for 36.5% (219/600). No significant difference was found between the antihypertensive regimen and the office BP level (χ2 = 4.461, P = .107), even when the proportion of the combination of a CCB + ACEI/ARB was higher by 15.8% among patients with an office BP of <120/80 mm Hg (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between antihypertensive regimens and office BP

| Office BP (mm Hg) | Antihypertensive regimens | χ2 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy | CCB plus ARB/ACEI | Other combination therapy | |||

| <120/80 (n = 165) | 39 (23.6) | 75 (45.4) | 51 (31.0) | 4.461 | .107 |

| ≥120/80 (n = 435) | 138 (31.7) | 129 (29.6) | 168 (38.6) | ||

| Total (n = 600) | 177 (29.5) | 204 (34.0) | 219 (36.5) | ||

Data are presented as n (%).

Abbreviations: ARB/ACEI, angiotensin receptor blocker/angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

4. DISCUSSIONS

In the present study, less than half of patients with controlled office BP had controlled early morning BP. Morning BP control was significantly correlated with the following factors: female sex, age of <65 years, no habitual snoring, no drinking, adequate physical activity, no habit of high salt intake, and was likely to be higher in patients who had office BP of <120/80 mm Hg and were treated with a combination of a CCB + ACEI/ARB.

Previous studies have shown that the rate of controlled morning BP is normally lower than that of office BP among patients with hypertension. A cross‐sectional study of 15 618 treated patients with hypertension from Greece, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and France suggested that the morning BP control rate was significantly lower than the office BP control rate in each age group (≥65 years, 33.1% vs 21.5%; P < .001 and <65 years, 41.9% vs 31.8%; P < .001).3 A study conducted in Beijing showed that 54.5% of patients had elevated morning BP21; however, the morning BP measurement was taken from 07:00 to 10:00 in the office and 64.1% of patients took antihypertensive drugs, which differs from studies above. The similar trend was also found among patients with controlled office BP. A multicenter registered study conducted in Japan showed that 48.3% of patients had controlled morning BP among treated patients with controlled office BP.4 Our findings are consistent this publications in that 45% achieved the target for morning BP control among similar patients.

In the current study, morning SBP increased by an average of 11.5 mm Hg compared with office BP. One previous study showed that the BP elevation was <15 mm Hg in patients without hypertension.15 The other study showed that the morning peak of the mean SBP was 26 mm Hg among patients with primary hypertension aged 46‐60 years and 31 mm Hg among patients aged >60 years.22 Morning BP rise might be a consequence of activation of the sympathetic nervous system after waking up.23, 24 Lifestyle changes can significantly reduce BP. The latest hypertension guideline concealed the fact that the usual impact of each lifestyle change is a 4‐5 mm Hg decrease in SBP and a 2‐4 mm Hg decrease in DBP based on office readings.19 Previous studies showed morning hypertension was likely to be higher in people of advanced age and was correlated with salt intake, current smoking, drinking, stress, and diabetes.4, 14, 15, 16, 25, 26 Our findings indicated morning BP control associated with a series of behavioral factors modification (ie, no habitual snoring, no drinking, adequate physical activity, and no habit of high salt intake).

Our study indicated that morning BP control was likely to be better in patients with office BP < 120/80 mm Hg; additionally, the change in the morning SBP and DBP was lower at this BP level. The latest hypertension guidelines defined office BP < 120/80 mm Hg as normal BP,19 but its benefit to morning BP control should be proved by large sample follow‐up studies.

BP control was attributed to antihypertensive regimen. Combination therapy of an ARB/AECI plus CCB or diuretic may improve 24‐hour BP control, including that in the early morning.27, 28 Recent hypertension guidelines recommend the use of a full or maximum dosage of antihypertensive drugs, the use of long‐acting antihypertensive drugs, and the use of a combination of a CCB + ARB/ACEI + diuretic for most patients with hypertension.19, 20 In the present study, combination therapy including an ARB/AECI and CCB used widely in the overall study population and may be beneficial to morning BP control compared with monotherapy.

In this study HBPM used for early morning BP assessment, it was different from that applied in other clinical studies, which more often used 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM). BP guideline recommended greater use of 24‐hour (ABPM) and/or HBPM for morning BP assessment and provided standard BP measurement protocol.14, 15, 16 The ownership of electronic sphygmomanometer was high at patients’ home with the initiatives of HBPM by hypertension guideline. Approximately 70% of patients with hypertension had a BP measuring device in Beijing and preferred to HBPM in routine BP measuring. HBPM is particularly suited to long‐term BP monitoring of treated patients because it is cheap and popular. With the development of BP telemonitoring technology and equipment, internet‐based remote monitoring and management of HBP is expected to become a new model of BP management in the future.

Several limitations of this study should be highlighted. First, home BP readings could not be obtained by electronic transmission, and thus, errors may be occurred by patients' tampering or adjustments. Furthermore, the poor coherence of the measurement method was likely to lead to measurement errors. Those errors were avoided by patients’ education and specific training in the proper measurement technique. Second, as the data collected without ambulatory BPM devices, the patterns of morning BP changes (dipping or non‐dipping pattern) was not predicted. Third, although we analyzed the effect of habitual snoring on morning BP control, sleep quality, and apnea were not assessed; thus, these results are relatively limited. Fourth, a habit of high salt intake was used to assess the relationship between salt intake and morning BP control because it is difficult to measure 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion and perform dietary salt intake weighting.

5. SUMMARIES

Less than half of patients had controlled early morning BP control among patients with controlled office BP, CVD prevention focus on office BP control, with additional emphasis on morning BP control in all the patients with hypertension. Morning BP control may be related to an office BP of <120/80 mm Hg, combination of a CCB and ACEI/ARB, and behavioral risk factors modification. Health providers should focus on office BP reduce that has great effect on averting CVD, with additional emphasis on morning BP assessment using HBPM in all the patients with hypertension.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hui‐Juan Zuo and Xian‐Tao Song conceived and designed the study, performed the analysis, interpreted results, and drafted the manuscript. Hui‐Juan Zuo and Jin‐Wen Wang enrolled subjects, performed face‐to‐face investigation and prepared the database for the analysis. Hong‐Xia Yang and Li‐Qun Deng enrolled subjects, performed clinical examinations and office BP measuring, and acquired HBPM data. Xian‐Tao Song interpreted results and performed critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the hypertension clinic staff for their contribution to this study, and the authors also thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Editing China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Zuo H‐J, Song X‐T, Yang H‐X, Deng L‐Q, Wang J‐W. Early morning home blood pressure control among treated patients with controlled office blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:1823–1830. 10.1111/jch.13736

Hui‐Juan Zuo, and Xian‐Tao Song, contributed equally to the study and are considered as co–first authors.

Funding information

This project was funded Capital clinical applied research and promotion achievements, funded by Beijing Municipal Science and Technology (No. Z16110000016139).

REFERENCES

- 1. Yusuf S, Joseph P, Rangarajan S, et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155722 individuals from 21 high‐income, middle‐income, and low‐income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelly TN, Gu D, Chen J, et al. Hypertension subtype and risk of cardiovascular disease in Chinese adults. Circulation. 2008;118:1558‐1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Redon J, Bilo C, Parati G. Home blood pressure control is low during the critical morning hours in patients with hypertension: the SURGE observation J study. Fam Pract. 2012;29:421‐426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ishikawa J, Kario K, Hoshide S, et al. Determinants of exaggerated difference in morning and evening blood pressure measured by self‐measured blood pressure monitoring in medicated hypertensive patients: Jichi morning hypertension research (J‐ MORE) study. Am J Hyperens. 2005;18:958‐965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Willich SN, Levy D, Rocco MB, et al. Circadian variation in the incidence of sudden cardiac death in the Framingham heart study population. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:801‐806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, et al. Prognostic value of the morning blood pressure surge in 5645 subjects from 8 populations. Hypertension. 2010;55:1040‐1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kario K, Saito I, Kushiro T, et al. Morning home blood pressure is a strong predictor of coronary artery disease, the Honext study. J AM Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1519‐1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, et al. Home b1ood pressure measurement has a stronger predictive power for mortality than does screening blood pressure measurement:a population—based observation in ohasama, Japan. J Hypenens. 1998;16:971‐975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoshide S, Yano Y, Haimoto H, et al. Morning and evening home blood pressure and risk of incident stroke and coronary artery disease in the Japanese general practice population: the Japan morning surge Home Blood Pressure Study. Hypertension. 2016;68:54‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kario K, Saito I, Kushiro T, et al. Home blood pressure and cardiovascular outcome in patients during antihypertensive therapy: primary results of HONEST, a large‐scale prospective, real‐world observational study. Hypertension. 2014;64:989‐996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoshide S, Yano Y, Haimoto H, et al. Morning and evening home blood pressure and risks of incidence stroke and coronary artery disease in the Japanese general practice population: the Japan Morning Surge‐Home Blood Pressure study. Hypertension. 2016;68:54‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Niiranen TJ, Hanninen M‐R, Johansson J, et al. Home‐measured blood pressure is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular risk than office blood pressure: the Finn‐Home study. Hypertension. 2010;55:1346‐1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kario K, Ishikawa J, Pickering TG, et al. Morning hypertension: the strongest independent risk factor for stroke in elderly hypertensive patients. Hypenens Res. 2006;29:58l‐587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang JG, Kario K, Chen CH, et al. Management of morning hypertension: a consensus statement of an Asian expert panel. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2018;20:39‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Council on hypertension of the Chinese Society of Cardiology . Chinese expert consensus on early morning blood pressure. Zhong Hua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2014;42:721‐725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shimamoto K, Ando K, Ishmitsu T, et al. Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for the management of hypertension. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guideline for management (JSH2014). Hypertens Res. 2014;37:253‐392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, et al. Status of hypertension in China: results of hypertension survey, 2012–2015. Circulation. 2018;137:2344‐2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957‐967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA /ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA /ASH/ASPC /NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary. JACC. 2018;71:2199‐2269.29146533 [Google Scholar]

- 20. The task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) . 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021‐3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang YP, Li ZP, Bai Q, et al. Current status of morning blood pressure control and medication of hypertensive patients in Beijing. Zhong Hua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2013;41:587‐588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, et al. Morning surge in b1ood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation. 2003;107:140l‐1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lamber EA, Chatzivlastou K, Schlaich M, et al. Morning surge in blood pressure is associated with reactivity of the sympathetic nervous system. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:783‐792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takagi T, Ohishi M, Ogihara T. Morning blood pressure variability and autonomic nervous activity. Noppoh Rinsho. 2006;64:44‐49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. White WB. The risk of waking‐up: impact of the morning surge in blood pressure. Hypertension. 2010;55:835‐837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castiglioni P, Parati G, Brambilla L, et al. Detecting sodium‐sensitivity in hypertensive patients: information from 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Hypertension. 2011;57:180‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bilo G, Koch W, Hoshide S, et al. Efficacy of olmesartan/amlodipine combination therapy in reducing ambulatory blood pressure in moderate‐to‐severe hypertensive patients not controlled by amlodipine alone. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:473‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kai H, Ueda T, Uchiwa H, et al. Benefit of losartan/hydrochlorothiazide‐fixed dose combination treatment for isolated morning hypertension: the MAPPY study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2015;37:473‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]