Abstract

Constipation is associated with cardiovascular events. Changes to the intestinal microbiota by constipation can induce atherosclerosis, blood pressure rise, and cardiovascular events. Constipation increases with age and often coexists with cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, strain at stool causes blood pressure rise, which can trigger cardiovascular events such as congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, acute coronary disease, and aortic dissection. However, because cardiovascular medical research often focuses on more dramatic interventions, the risk from constipation can be overlooked. Physicians caring for patients with cardiovascular disease should acknowledge constipation and straining with it as important cardiovascular risk, and prematurely intervene to prevent it. The authors review and discuss the relationship between constipation and cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, constipation, hemodynamic atherothrombotic syndrome, intestinal microbiota, strain at stool, synergistic resonance hypothesis of blood pressure variability

1. INTRODUCTION

Constipation has been reported to be linked to the occurrence of cardiovascular events.1 In the Japanese general population, low‐frequency defecation (once per 2 to 3 days) is a significantly higher risk of cardiovascular deaths than high‐frequency defecation (more than once per day).2 Another study has shown that the prevalence of constipation among Japanese patients hospitalized for cardiovascular disease was 47%, and 46% of this population (ie, 21.6% of the total population) only developed constipation after admission.3 The link between constipation and cardiovascular events might involve a change in intestinal microbiota. Recently, the intestinal microbiota have received attention as a novel risk factor for cardiovascular events.4 Moreover, many papers have reported on the association between changes in the intestinal microbiota and increased blood pressure (BP),5 progression of atherosclerosis,4 and cardiovascular disease.6 Oxidative stress may be another link between constipation and cardiovascular disease.7 Nonetheless, because cardiovascular medical research often focuses on more dramatic interventions, the association between constipation and cardiovascular disease is often overlooked.

2. MECHANISM OF THE LINKAGE BETWEEN CONSTIPATION AND CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Aging is well recognized as one of the most important risks for both constipation and cardiovascular disease.8 Therefore, the increase in the prevalence of constipation with age parallels that of cardiovascular disease. Figure 1 shows a possible mechanism underlying the association between constipation and the onset of cardiovascular events. Various factors can contribute to the hardening of stool and the weakening of bowel movement. Patients with cardiovascular disease, especially when complicated with heart failure, are instructed to restrict their water intake and are often administered diuretics, which can promote constipation. Moreover, various factors after hospitalization can also promote constipation, such as decreased activity, environmental changes. Chronic constipation induces mental stress,9 which may be related to rising BP. Constipation also leads to strain at stool, which can include breathing in a strained manner similar to the Valsalva maneuver. Namely, first the BP increases and the heart rate drops transiently. Second, the BP falls and the heart rate rises. Third, the BP transiently drops in an instant. Fourth, the BP reactively rises (Table 1).10

Figure 1.

Relationship between constipation and cardiovascular disease

Table 1.

Previous reports on the relationship between defecation and blood pressure or cardiovascular risk

| Author | Type of study | Population | Number of patients | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmoirago‐Blotcher et al1 | Prospective cohort study | Postmenopausal women | 93 676 | Postmenopausal women with constipation had a 23% higher risk of cardiovascular events than those without during 6.9‐y follow‐up. |

| Honkura et al2 | Observational study | Japanese general population | 45 122 | Low frequency of defecation (1 time/2‐3 d) had higher risk of cardiovascular death than normal frequency of defecation (≥1 time/d) during 13.3‐year follow‐up. |

| Fujii et al3 | Observational study | Japanese inpatient | 59 | The prevalence of constipation was 47% among patients hospitalized for CV disease and 46% of this population (ie, 21.6% of the total population) experienced constipation only after admission. |

| Akazawa et al11 | Cross‐sectional study | Japanese general population | 10 elderly (mean 84.3 y) five young (mean 22.6 y) | In elderly, elevated BP was observed just before defecation (+15 mm Hg), and its elevation continued to increase during defecation (+29 mm Hg). Increased BP was remained 1 h after defecation (+11 mm Hg). In young, those findings were not observed. |

| Tochikubo12 | Observational study | Unknown | 7 | Strain at stool caused a large BP rise of about 70 mm Hg. |

| Imai et al13 | Cross‐sectional study | Healthy adults (mean 32.7 y) | 23 | At an intrathoracic pressure of 30 mm Hg, the change of systolic BP was 41.43 ± 13.30 mm Hg. |

Despite these facts, there have been only a few reports about the association between defecation and elevated BP. In 10 elderly patients (mean age 84.3 years), elevated BP was observed just before defecation, and the BP continued to rise during defecation. Interestingly, the increase in BP remained for 1 hour after defecation in these patients. On the other hand, similar findings were not observed in five young people (mean age 22.6 years).11 In addition, another paper reported that strain at stool caused a large systolic BP rise of about 70 mm Hg.12 At an intrathoracic pressure of 30 mm Hg by strain at stool, the systolic BP increased to 41.43 ± 13.30 mm Hg in a group of healthy adults (mean age 32.7 years).13 It is known that BP fluctuation including morning surge can trigger cardiovascular events.14, 15 For example, if an elderly patient with morning BP surge performs strain at stool early in the morning in a cold bathroom in winter, his/her systolic BP may undergo an exaggerated increase. Some hypertensive patients also exhibit morning BP surge early in the morning. Finally, a change in room temperature often induces BP surge, especially in elderly patients. Interestingly, it has been reported that BP increases by 30 mm Hg during defecation11 and also by 30 mm Hg in response to room temperature change.16

We have treated patients whose cases indicated the possibility of an association between constipation and cardiovascular events. One patient with a history of myocardial infarction had a bowel movement in the early morning one day during the winter, but before successfully defecating he experienced dyspnea and developed heart failure. Another patient suffered a sudden onset of back pain when straining to release his stool, and he experienced an acute myocardial infarction.

The similar BP effects of cold and strain at stool might be explained by the synergistic resonance hypothesis of BP variability. Dynamic surge generated by the resonance of surges with different phases triggers event onset. The BP exhibits yearly, seasonal, visit‐to‐visit, day‐by‐day, diurnal, and beat‐by‐beat variability, and all these forms of variability are associated with endothelial cell disorder, arteriolar remodeling, and enhancement of large vessel stiffness. The central BP, the BP applied to local blood vessels and organs, and the increase in variability of the blood flow themselves form a vicious cycle in which disorders of the large and small blood vessels develop, along with polyvascular diseases at different sites, and synergistic acceleration of organ disorders. This disease concept has been designated hemodynamic arteriosclerotic syndrome (HATS).17

As the BP rises, the risk of cardiovascular disease increases. For example, when systolic BP rises by 20 mm Hg, the risk of developing cardiovascular disease doubles.18

3. UNIQUE CHARACTERISTICS OF CONSTIPATION IN PATIENTS WITH CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Patients in the acute phase of cardiovascular disease are often confined to bed rest. Therefore, these patients are under high risk of developing constipation, and even if they defecate every day, their physicians should consider whether their stool is hard and whether their bowel movement was facilitated. For these evaluations, the Bristol scale may be useful.19 Moreover, because constipation may be an initial symptom of colon cancer, it is important to ask patients whether they have experienced constipation with thin stool or body weight loss. If necessary, physicians should order fecal occult blood tests. Screening for gastrointestinal cancer, which may be a source of bleeding, is important, because patients with cardiovascular disease frequently take antithrombotic drugs.

Hypertension is not only a major risk of cardiovascular disease20 but also a trigger of congestive heart failure. The BP of a woman hospitalized with congestive heart failure at our institution rose to 204/88 mm Hg when she strained to release her stool, and as a result, she developed flash pulmonary edema even though her heart failure condition has been compensated and she was able to walk around her hospital room. She had not defecated during her hospitalization.

There is a link between constipation and the management of hypertension. Calcium channel blockers, one of the major classes of antihypertensive drugs, promote constipation due to their suppression of smooth muscle movement.21

Patients with heart failure often use diuretics and restrict water and sodium for fluid volume control. This decreases the amount of water in the body in general, and the amount of water in the gut specifically. In patients with right heart failure, impairment of intestinal peristalsis occurs in the edematous gut. Other factors related to gastrointestinal disorder in heart failure patients, including hypoperfusion, abnormality of intestinal permeability, and increase of intestinal bacterial colonization, have been reported.22, 23 Thus, the improvement of heart failure generally parallels the amelioration of constipation, abdominal distention, and anorexia.

In acute coronary syndrome, vagal activity is reduced while sympathetic nerve activity is increased,24 resulting in constipation. In addition, patients with acute myocardial infarction are often confined to bed rest after catheter intervention. A longer period of bed rest is required in patients treated with intra‐aortic balloon pumping. Patients required to rest in bed for long periods are at risk of constipation not only due to the rest‐induced decrease of intestinal peristalsis, but also because of the difficulty and shame attendant on defecation in bed. The BP rise upon defecation may induce cardiac rupture, acute heart failure due to increased afterload, and ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation.

The main causes of aortic dissection are hypertension and atherosclerosis, although forms of vascular fragility, such as Marfan syndrome, may also be involved.25 In the acute phase of aortic dissection, a longer term of bed rest is required compared with other cardiovascular diseases. As a result, patients with aortic dissection may be more likely to develop constipation. We need to watch for intestinal necrosis or paralytic ileus due to occlusion of the nutrient blood vessels and spread of inflammation when dissection reaches the abdominal aorta.

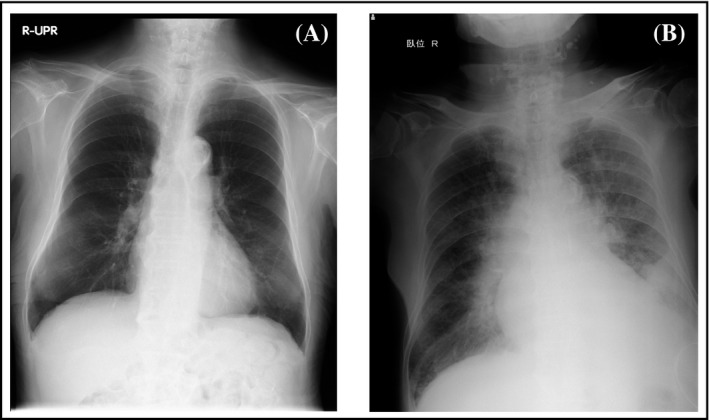

Aortic valve stenosis may be a specific condition in which physicians should watch for constipation. Because strain at stool increases afterload, patients with aortic valve stenosis may not be able to maintain cardiac output during a strained defecation. Such conditions could easily trigger chest pain, syncope, or heart failure. We treated an 89‐year‐old man with congestive heart failure due to severe aortic valve stenosis. His aortic valve peak flow velocity was >5 m/s, and his valve area was <0.5 cm2. His congestion improved, and he was able to walk freely within the ward. However, after he defecated one morning, a nurse discovered the patient lying beside the toilet with facial pallor, cyanosis, and sweating. Figure 2 provides the X‐rays taken before and immediately after this event. His flash pulmonary edema was considered to have occurred due to straining to release a stool.

Figure 2.

Chest X‐ray of severe aortic valve stenosis patients: A, the day before the event, B, flash pulmonary edema after defecation

4. MANAGEMENT OF CONSTIPATION IN PATIENTS WITH CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

As a first step in the management of these cases, physicians should intervene in the lifestyle of patients. Patients should be instructed to allow themselves adequate time and privacy for defecation.26 In addition, an intake of 20‐35 g/d of dietary fiber and 1.5‐2.0 L/d of water intake is necessary for ideal defecation.27 As described above, however, patients with heart failure will often be instructed to restrict their water intake.

Biofeedback retraining of muscles related to defecation may be effective for treating chronic constipation irrespective of the presence or absence of pelvic floor dysfunction, and this method has no side effects.28

Despite the desirability of the above methods, most cardiovascular patients will require medication to promote defecation. Stool softeners and stimulant laxatives are often chosen. Bulking agents such as methylcellulose, polycarbophil, and psyllium absorb water in the intestine and soften the stool.29 Osmotic laxatives such as magnesium agents, lactulose, sorbitol,30 and polyethylene glycol31 draw water into the intestinal lumen. Magnesium oxide, magnesium hydroxide, and magnesium citrate are suggested to be effective for constipation. In patients with impaired renal function (especially glomerular filtration rate <30 ml/min), there is a delay in magnesium excretion, so caution must be taken to avoid hypermagnesemia.32 However, hypermagnesemia might occur even in the patients with normal renal function.33 Patients with cardiovascular disease are often complicated with renal dysfunction.34 Hypermagnesemia causes various symptoms, electrocardiographic changes, and arrhythmias.35 If physicians see emergency patients with high‐grade bradycardia and atrioventricular block, they should confirm the oral administration and check the renal function or electrolytes, including magnesium. Lubiprostone,29 which is a chloride channel activator, and linaclotide,36 which is a guanylate cyclase C receptor agonist, move water into the intestinal lumen. These agents may be substitutes for magnesium supplementation in patients under high risk of hypermagnesemia.

A traditional Chinese herbal medicine containing rhubarb is often used for constipation, but its effects are due to laxative‐type stimulation37 and can give rise to adverse effects such as nephrotoxicity.38 Mashiningan in Japanese herbal medicine also contains rhubarb, whereas cannabis sativa seed and apricot seed mainly increase the defecation frequency and amount of fecal matter, and can be used to soften the stool.39 Because traditional Chinese herbal medicines containing licorice promote body fluid retention, physicians should apply these medicines with care, especially in patients with heart failure.40

Finally, the bathroom environment is important, including the room temperature and the temperature of the toilet seat.22

5. CONCLUSIONS

Constipation is one of the risks of cardiovascular disease, and patients with cardiovascular disease tend to be constipated. Physicians caring for patients with cardiovascular disease should acknowledge constipation and straining with it as important cardiovascular risk, and prematurely intervene to prevent it.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Ishiyama Y, Hoshide S, Mizuno H, Kario K. Constipation‐induced pressor effects as triggers for cardiovascular events. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:421–425. 10.1111/jch.13489

REFERENCES

- 1. Salmoirago‐Blotcher E, Crawford S, Jackson E, et al. Constipation and risk of cardiovascular disease among postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2011;124:714‐723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Honkura K, Tomata Y, Sugiyama K, et al. Defecation frequency and cardiovascular disease mortality in Japan: The Ohsaki cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2016;246:251‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fujii H, Yorozu T, Harada H, et al. Junkankishikkan to benpi [Cardiovascular Disease and Constipation]. Pharm Med. 1994;12:205‐211 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L‐carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:576‐585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, et al. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;65:1331‐1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;72:57‐63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vermorken A, Andrès E, Cui Y, et al. Chronic constipation – a warning sign for oxidative stress? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:385‐386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corella D, Ordovás JM. Aging and cardiovascular diseases: the role of gene‐diet interactions. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;18:53‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Merkel IS, Locher J, Burgio K, et al. Physiologic and psychologic characteristics of an elderly population with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1854‐1859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kawahara Y.Physiological and psychological reaction at the time of bathing and excretion, and need for non‐room heating. (in Japanese).

- 11. Akazawa H, Kajihara M, Togo M, et al. Variations in blood pressure during daily activities in the elderly ‐effects of bathing and defecation. The Autonomic Nervous System. 2000;37:431‐439. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tochikubo O. Ketsuatsu no sokuteiho to rinsho hyoka [Measurement method of blood pressure and clinical evaluation]. Medical Tribune. 1991. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Imai M, Hirai M, Kuwahara Y, et al. Influence of intrathoracic pressure at defecation on cardiovascular system. Jpn J Nurs Art Sci. 2011;10:111‐120. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Brien E, Kario K, Staessen JA, et al. Patterns of ambulatory blood pressure: clinical relevance and application. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2018;20:1112‐1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang JG, Kario K, Chen CH, et al. Management of morning hypertension: a consensus statement of an Asian expert panel. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2018;20:39‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tochihara Y, Hashiguchi N, Yadoguchi I, et al. Effects of room temperature on physiological and subjective responses to bathing the elderly. J Hum Environ Syst. 2012;15:13‐19. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kario K. Hemodynamic arteriosclerotic syndrome – a vicious cycle of hemodynamic stress and vascular disease. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2018;20:1073‐1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizibash N, et al. Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903‐1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool from scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920‐924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kario K. The HOPE Asia Network for "zero" cardiovascular events in Asia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2018;20:212‐214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elliott WJ, Ram CV. Calcium channel blockers. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:687‐689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krack A, Richartz BM, Gastmann A, et al. Studies on intragastric PCO2 at rest and during exercise as a marker of intestinal perfusion in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:403‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Romeiro FG, Okoshi K, Zornoff LA, et al. Gastrointestinal changes associated to heart failure. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;98:273‐277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schwartz PJ, Vanoli E, Stramba‐Badiale M, et al. Autonomic mechanisms and sudden death: new insights from analysis of baroreceptor reflexes in conscious dogs with and without a myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1988;78:969‐979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, et al. Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665‐669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Spinzi G, Amato A, Imperiali G, et al. Constipation in the elderly: management strategies. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:469‐474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anti M, Pignataro G, Armuzzi A, et al. Water supplementation enhances the effect of high‐fiber diet on stool frequency and laxative consumption in adult patients with functional constipation. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:727‐732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ba‐Bai‐Ke‐Re MM, Wen NR, Hu YL, et al. Biofeedback‐guided pelvic floor exercise therapy for obstructive defecation: an effective alternative. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9162‐9169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fleming V, Wade WE. A review of laxative therapies for treatment of chronic constipation in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:514‐550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lederle FA, Busch DL, Mattox KM, et al. Cost‐effective treatment of constipation in the elderly: a randomized double‐blind comparison of sorbitol and lactulose. Am J Med. 1990;89:597‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:936‐971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Horibata K, Tanoue A, Ito M, et al. Relationship between renal function and serum magnesium concentration in elderly outpatients treated with magnesium oxide. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:600‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clark BA, Brown RS. Unsuspected morbid hypermagnesemia in elderly patients. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12:336‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu M, Li XC, Lu L, et al. Cardiovascular disease and its relationship with chronic kidney disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:2918‐2926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoshida M. Hypermagnesemia and hypomagnesemia. Nippon Rinsho. 1991;49(suppl):893‐895 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lembo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ, et al. Two randomized trials of linaclotide for chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:527‐536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xiao P, He L, Wang L. Ethnopharmacologic study of Chinese rhubarb. J Ethnopharmacol. 1984;10:275‐293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yan M, Zhang LY, Sun LX, et al. Nephrotoxicity study of total rhubarb anthraquinones on Sprague Dawley rats using DNA microarrays. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:308‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iizuka N, Hamamoto Y. Constipation and herbal medicine. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chamberlain TJ. Licorice poisoning, pseudoaldosteronism, and heart failure. JAMA. 1970;213:1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]