Abstract

This study assessed the efficacy and safety of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril/valsartan vs olmesartan in Asian patients with mild‐to‐moderate hypertension. Patients (N = 1438; mean age, 57.7 years) with mild‐to‐moderate hypertension were randomized to receive once daily administration of sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg (n = 479), sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg (n = 473), or olmesartan 20 mg (n = 486) for 8 weeks. The primary endpoint was reduction in mean sitting systolic blood pressure (msSBP) from baseline with sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg vs olmesartan 20 mg at Week 8. Secondary endpoints included msSBP reduction with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg, and reductions in clinic and ambulatory BP and pulse pressure (PP) vs olmesartan. In addition, changes in msBP from baseline in the Chinese subpopulation, elderly (≥65 years), and in patients with isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) were assessed. Sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg provided a significantly greater reduction in msSBP than olmesartan 20 mg at Week 8 (between‐treatment difference: −2.33 mm Hg [95% confidence interval (CI) −4.00 to −0.66 mm Hg], P < 0.05 for non‐inferiority and superiority). Greater reductions in msSBP were also observed with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg vs olmesartan 20 mg (−3.52 [−5.19 to −1.84 mm Hg], P < 0.001 for superiority). Similarly, greater reductions in msBP were observed in the Chinese subpopulation, in elderly patients, and those with ISH. In addition, both doses of sacubitril/valsartan provided significantly greater reductions from baseline in nighttime mean ambulatory BP vs olmesartan. Treatment with sacubitril/valsartan 200 or 400 mg once daily is effective and provided superior BP reduction than olmesartan 20 mg in Asian patients with mild‐to‐moderate hypertension and is generally safe and well tolerated.

Keywords: ambulatory blood pressure/home blood pressure monitor, antihypertensive therapy, Asian patients, hypertension—general

1. INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular (CV) disease and a leading cause of mortality and morbidity globally with an estimated prevalence of 1 billion adults, which is projected to increase to 1.5 billion by 2025.1 The prevalence of hypertension in Asian countries2 ranges from 30% in Korea to 39% in China.3 Because of a rapid increase in the aging population, the incidence of hypertension in Asia is expected to increase, with 60% of patients aged >60 years being diagnosed with hypertension in China.3 Compared with the Western population, elevated blood pressure (BP) is more strongly associated with the incidence of stroke than with coronary artery disease in Asians.4, 5 This contributes to a substantial health and socio‐economic burden in this region along with other underlying factors, such as a Westernized life style and increasing prevalence of obesity and diabetes.

The current hypertension guidelines from China, Korea, and Taiwan recommend the use of calcium channel blockers (CCBs), angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), diuretics, and beta‐blockers as first‐line antihypertensive therapies.6 However, BP control (SBP/DBP <140/90 mm Hg) remains sub‐optimal in Asians, with only 25% of treated Chinese patients achieving the target BP.3

Sacubitril/valsartan (formerly known as LCZ696), a first‐in‐class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) that provides simultaneous neprilysin inhibition and angiotensin receptor blockade, was recently approved for the treatment of chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, based on its superior benefits over enalapril in the PARADIGM‐HF trial.7, 8 Previous studies with sacubitril/valsartan also showed superior reductions in clinic and ambulatory BP and pulse pressure (PP) in Western and Asian patients with mild‐to‐moderate hypertension10, 11 compared with valsartan10 or placebo.11 The PARAMETER study showed that sacubitril/valsartan treatment, administered at daily doses of 400 mg, resulted in superior improvement in central hemodynamics in elderly patients with systolic hypertension and arterial stiffness compared with olmesartan at daily doses of 40 mg.12 However, the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan in Chinese patients with hypertension has not been well established from previous studies.

In this study conducted in predominantly Chinese patients, we assessed the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan in comparison with olmesartan, an ARB, and a widely used antihypertensive agent, in Asian patients with mild‐to‐moderate essential hypertension.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patient population

Asian patients aged ≥18 years with mild‐to‐moderate essential hypertension (office mean sitting systolic blood pressure ≥140 to <180 mm Hg), untreated or treated with antihypertensive medications, were included. Chinese patients were recruited to comprise ~80% of the total population based on the pre‐specified study protocol requirement. Patients treated for hypertension were required to have received antihypertensive medications during the last 4 weeks prior to screening, with a mean sitting systolic blood pressure (msSBP) ≥140 to <180 mm Hg at screening and ≥150 to <180 mm Hg at randomization following a 3‐ to 4‐week placebo run‐in phase. Patients untreated for hypertension were required to have msSBP ≥150 and <180 mm Hg at both screening and randomization.

Patients with severe hypertension (mean sitting diastolic blood pressure [msDBP] ≥110 mm Hg and/or msSBP ≥180 mm Hg), secondary hypertension, history of angioedema, myocardial infarction or transient ischemic cerebral attack during 12 months prior to screening visit, or with uncontrolled type 1 and 2 diabetes, pregnant women or nursing mothers were excluded.

2.2. Study design

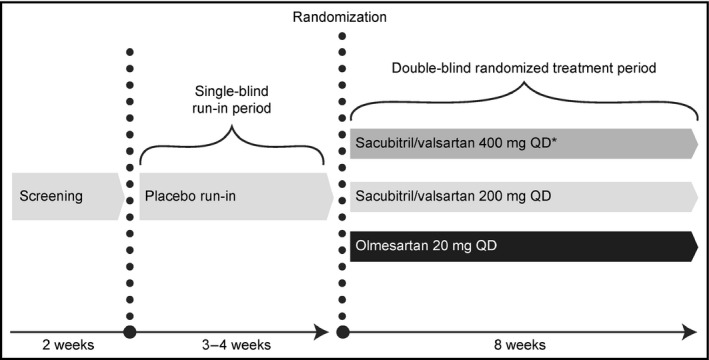

This was a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, active‐controlled, parallel‐group study in Asian patients with mild‐to‐moderate hypertension. After the initial screening, all eligible patients entered a 3‐ to 4‐week placebo run‐in period with all antihypertensive medications discontinued. Patients who completed the run‐in and met the entry criteria were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to double‐blinded treatment with sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg, 400 mg (up‐titrated following 1‐week treatment with sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg), or olmesartan 20 mg once daily, a commonly used dose in China and other Asian countries,13 for 8 weeks (Figure 1). The doses of sacubitril/valsartan (200 and 400 mg) used in the current study were based on previous studies in hypertensive patients where clinically relevant, dose‐dependent (100, 200, and 400 mg) antihypertensive effects were demonstrated with sacubitril/valsartan.10, 11, 14 All eligible patients were randomized using an Interactive Response Technology (IRT) system. A randomization list was produced by the IRT provider using a validated system that automates the random assignment of patient numbers to randomization numbers. Patients were instructed to take their study medication once daily in the morning for the duration of the study.

Figure 1.

Study design. *Patients were up‐titrated to sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg after receiving sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg for 1 week. OD, once daily

All patients provided written informed consent before screening. The clinical study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board at each center, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01785472).

2.3. Efficacy assessments

The primary efficacy assessment was testing the hypothesis of non‐inferiority for sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg vs olmesartan 20 mg for msSBP reductions between baseline and Week 8 and testing for superiority, if the hypothesis of non‐inferiority was achieved. Secondary objectives included msSBP reduction between baseline and Week 8 with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg vs olmesartan 20 mg, and changes from baseline at the Week 8 endpoint in msDBP and mean sitting pulse pressure (msPP), 24‐hour mean ambulatory BP (maSBP, maDBP, and maPP), and mean daytime/nighttime maSBP and maDBP in a subset of patients with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). ABPM assessments were carried out using a SpaceLabs Healthcare ambulatory BP monitoring device (model 90207‐1Q). The ABPM device was placed on the non‐dominant arm in the morning of the office visit and ambulatory BP was then monitored for a minimum of 24 hours. Ambulatory BP measurements were collected at baseline and at the end of study (8 weeks). Daytime measurements were defined as 6 am‐10 pm and nighttime as 10 pm‐6 am for data analyses.

Additional secondary objectives included the proportion of patients achieving overall BP control (msSBP/msDBP <140/90 mm Hg), SBP response (msSBP <140 mm Hg or a reduction from baseline of ≥20 mm Hg), and DBP response (msDBP <90 mm Hg or a reduction from baseline of ≥10 mm Hg) compared with olmesartan 20 mg. In addition, BP control rates were also assessed according to the current 2017 ACC/AHA/ASH guidelines (msSBP/msDBP <130/80 mm Hg).15 Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the change in msBP from baseline in the Chinese subpopulation, elderly patients (aged ≥65 years), and patients with isolated systolic hypertension (ISH, msDBP<90 mm Hg, and msSBP≥140 mm Hg at baseline).

2.4. Safety assessments

Safety assessments included monitoring of all adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), and regular monitoring of vital signs and clinical laboratory tests.

2.5. Statistical analysis

A sample size of 1425 randomized patients was targeted based on the primary efficacy variable and a standard deviation (SD) of 14 mm Hg to attain ≥90% power for the non‐inferiority test, with pre‐specified non‐inferiority margin of 2 mm Hg at a one‐sided significance level of 0.025 under the alternative hypothesis that the sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg group has a greater msSBP reduction of ≥1.5 mm Hg than the olmesartan 20 mg group. A sample size of 1125 patients was targeted for the Chinese subpopulation to attain 90% power for the superiority assessment under the alternative hypothesis that the treatment difference is 3.5 mm Hg at a two‐sided significance level of 0.05, assuming a 10% drop‐out rate. In addition, for ABPM assessments, a sample size of 191 completed patients (per treatment arm) was targeted to provide 90% power. This was based on the change from baseline in 24‐hour maSBP and a SD of 12 mm Hg, assuming a treatment difference of 4.0 mm Hg at a two‐sided significance level of 0.05.

Reductions in msSBP from baseline were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with treatment and region as factors and baseline value as a covariate. Non‐inferiority was considered to be achieved at a one‐sided significance level of 0.025 if the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for this difference was below the non‐inferiority margin of 2 mm Hg. If the non‐inferiority test was statistically significant, a superiority test for sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg vs olmesartan 20 mg was performed at a two‐sided significance level of 0.05.

The changes in msDBP, msPP, and the secondary variables were analyzed using two‐way ANCOVA with treatment and region as factors and baseline value as a covariate. The changes in 24‐hour ambulatory BP and daytime/nighttime ambulatory BP were analyzed using ANCOVA for repeated measures with treatment, region, post‐dosing hour (or time [daytime/nighttime]), and treatment‐by‐post‐dosing hour (or time) interaction as factors and baseline 24‐hour maBP as a covariate.

Frequency of AEs, SAEs, and notable laboratory abnormalities was measured for the safety set, which included all patients who received at least one dose of the double‐blind study medication.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics and baseline characteristics

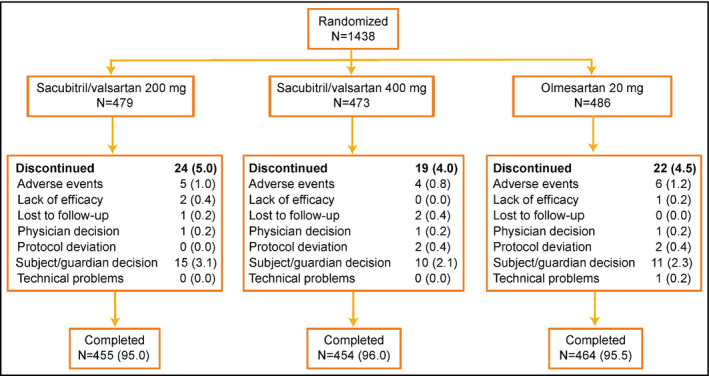

The disposition of the 1438 randomized patients is shown in Figure 2. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were comparable among the treatment groups (Table 1). The majority of patients were of Chinese (85%) ethnicity (comprising patients from China [79%], Taiwan, and Hong Kong). The mean age of the patients was 57.7 years and 25.4% were elderly (aged ≥65 years). The mean duration of hypertension was 10.2 years, with the majority (98%) of patients being previously diagnosed with or treated for hypertension. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics of the Chinese subpopulation were similar to the main cohort and were comparable between treatment groups (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Patient disposition. Data are n (%). *Three patients were mis‐randomized and did not receive double‐blind medication and were excluded from the full analysis set and safety set; one additional patient, who was randomized but did not take study medication, was excluded from the safety set

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (Full analysis set)

| Demographic/baseline variable | Sacubitril/valsartan | Olmesartan | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

200 mg N = 479a |

400 mg N = 472a |

20 mg N = 484a |

|

| Age (y) | 57.5 ± 10.17 | 58.1 ± 9.71 | 57.4 ± 10.14 |

| ≥65 y, n (%) | 121 (25.3) | 132 (28.0) | 112 (23.1) |

| ≥75 y, n (%) | 20 (4.2) | 19 (4.0) | 22 (4.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 252 (52.6) | 243 (51.5) | 261 (53.9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Chinese | 407 (85.0) | 403 (85.4) | 410 (84.7) |

| Korean | 34 (7.1) | 32 (6.8) | 33 (6.8) |

| Southeast Asian | 30 (6.3) | 34 (7.2) | 34 (7.0) |

| Other | 8 (1.7) | 3 (0.6) | 7 (1.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 ± 3.91 | 26.3 ± 3.56 | 26.4 ± 3.92 |

| Duration of hypertension history (y) | 10.0 ± 8.44 | 10.3 ± 8.67 | 10.2 ± 8.38 |

| Hypertension naïveb, n (%) | 10 (2.1) | 8 (1.7) | 11 (2.3) |

| Isolated systolic hypertension, n (%) | 209 (43.6) | 222 (47.0) | 217 (44.8) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 81 (16.9) | 75 (15.9) | 77 (15.9) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 111 (23.2) | 110 (23.3) | 91 (18.8) |

| Non‐alcoholic fatty liver, n (%) | 31 (6.5) | 24 (5.1) | 27 (5.6) |

| Mean eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 85.4 (17.1) | 85.3 (18.0) | 85.0 (17.1) |

| eGFR ≥30 to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 20 (4.2) | 38 (8.1) | 28 (5.8) |

| msSBP, mm Hg | 158.0 ± 7.15 | 157.9 ± 6.73 | 158.0 ± 6.53 |

| msDBP, mm Hg | 90.7 ± 9.37 | 89.8 ± 9.46 | 90.8 ± 9.57 |

| msPP, mm Hg | 67.2 ± 10.68 | 68.1 ± 10.47 | 67.2 ± 10.32 |

| 24‐h maSBP, mm Hg | 143.2 ± 11.93 | 142.8 ± 12.04 | 141.4 ± 11.84 |

| 24‐h maDBP, mm Hg | 86.3 ± 9.40 | 86.0 ± 9.33 | 86.7 ± 9.52 |

| 24‐h maPP, mm Hg | 56.9 ± 10.21 | 56.9 ± 10.24 | 54.7 ± 9.59 |

BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; maDBP, mean ambulatory diastolic blood pressure; maPP, mean ambulatory pulse pressure; maSBP, mean ambulatory systolic blood pressure; msDBP, mean sitting diastolic blood pressure; msPP, mean sitting pulse pressure; msSBP, mean sitting systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Data are presented as mean ± SD unless specified.

Full analysis set.

Patients newly diagnosed with hypertension.

3.2. Clinic blood pressure

The least squares mean (LSM) reductions (95% CI) in msSBP were greater for the sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg vs olmesartan 20 mg group by −2.33 (−4.00 to −0.66) mm Hg demonstrating the non‐inferiority of sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg to olmesartan 20 mg (P < 0.001). Further, sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg provided superior msSBP reductions from baseline to the Week 8 endpoint (P = 0.006) (Table 2). In addition, sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg provided significantly greater reductions in msSBP from baseline than olmesartan at Week 8 with a between‐treatment LSM difference of −3.52 (−5.19 to −1.84; P < 0.001) mm Hg (Table 2). The greater msSBP reductions in the sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg and 400 mg groups compared with olmesartan 20 mg were evident from Week 1 through the end of the 8‐week study.

Table 2.

Mean changes from baseline in msBP and msPP at Week 8 endpoint by treatment group

| BP |

Olmesartan 20 mg (N = 479) |

Sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg (N = 477) |

Sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg (N = 469) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline | Change from baseline | vs olmesartana | Change from baseline | vs olmesartana | |

| msSBP, mm Hg | −18.15 | −20.48 | −2.33 (−4.0, −0.66); P = 0.006b | −21.67 | −3.52 (−5.19, −1.84); P < 0.001 |

| msDBP, mm Hg | −6.86 | −8.10 | −1.24 (−2.26, −0.22); P = 0.018 | −8.80 | −1.93 (−2.96, −0.91); P < 0.001 |

| msPP, mm Hg | −11.25 | −12.35 | −1.09 (−2.25, 0.06); P = 0.064 | −12.93 | −1.68 (−2.84, −0.51); P = 0.005 |

BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; LSM, least square mean; msDBP, mean sitting diastolic blood pressure; msPP, mean sitting pulse pressure; msSBP, mean sitting systolic blood pressure.

Data are LSM treatment difference (95% CI).

Indicates statistically significant superiority of sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg compared to olmesartan 20 mg at the two‐sided 0.05 level.

Similarly, greater reductions from baseline to Week 8 in msDBP (P = 0.018) and in msPP (P = 0.064) were observed with sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg compared with olmesartan 20 mg. Sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg provided numerically greater reductions in msDBP and msPP than sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg (Table 2).

The findings of additional subgroup analyses on the changes from baseline in msSBP/msDBP in elderly patients (n = 365) and in patients with ISH (n = 630) were similar with the overall patient population. The mean reductions from baseline in msSBP at the Week 8 endpoint were greater with sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg (−18.17 mm Hg), and 400 mg (−20.52 mm Hg), than olmesartan 20 mg (−17.06 mm Hg) in elderly patients (aged ≥65 years) and in patients with ISH (−18.96, −21.54, and −18.36 mm Hg, respectively). Both the doses of sacubitril/valsartan also showed greater mean msDBP reductions in the elderly subgroup (−7.16, −7.37, and −5.44 mm Hg, respectively) and in patients with ISH (−4.94, −5.75, and −4.60 mm Hg, respectively).

A pre‐specified subgroup analysis of the Chinese population (n = 1132) for change from baseline in msSBP to the Week 8 endpoint showed that the LSM (95% CI) between‐treatment difference was −1.70 (−3.57 to 0.17; P = 0.075) mm Hg for sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg vs olmesartan 20 mg groups. Treatment with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg resulted in significantly greater reductions in msSBP (LSM difference [95% CI] −3.15 [−5.03 to −1.27] mm Hg; P = 0.001) than olmesartan 20 mg, demonstrating the superiority of sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg over olmesartan 20 mg in Chinese patients. Similarly, significantly greater reductions from baseline to Week 8 in msDBP were observed with sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg (LSM difference [95% CI] −1.25 [−2.39 to −0.10] mm Hg; P = 0.032) and sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg (−1.89 [−3.04 to −0.74] mm Hg; P = 0.001) than olmesartan. Greater reductions in msPP were also observed with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg (−1.34 [−2.64 to −0.03] mm Hg; P = 0.044) than olmesartan.

3.3. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

Of the 677 patients with valid baseline ABPM, 554 had both baseline and 8‐week endpoint assessments. Both doses of sacubitril/valsartan provided significantly greater LSM reductions in 24‐hour maSBP from baseline to Week 8 compared with olmesartan 20 mg, with between‐treatment differences (95% CI) of −1.81 mm Hg (−3.14 to −0.47; P = 0.008) and −2.50 mm Hg (−3.85 to −1.16; P < 0.001) in favor of sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg and 400 mg, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean changes from baseline in ambulatory BP, PP, and in daytime and nighttime ambulatory BP at Week 8 endpoint by treatment group

| BP, mm Hg |

Olmesartan 20 mg (N = 182) |

Sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg (N = 188) |

Sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg (N = 184) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline | Change from baseline | vs olmesartana | Change from baseline | vs olmesartana | |

| maSBP | −10.26 | −12.07 | −1.81 (−3.14, −0.47); P = 0.008 | −12.76 | −2.50 (−3.85, −1.16); P < 0.001 |

| maDBP | −5.61 | −6.36 | −0.75 (−1.60, 0.10); P = 0.083 | −6.82 | −1.21 (−2.07, −0.36); P = 0.006 |

| Daytime maSBP | −10.36 | −11.38 | −1.01 (−3.30, 1.28); P = 0.386 | −12.36 | −1.99 (−4.29, 0.30); P = 0.089 |

| Daytime maDBP | −5.67 | −5.85 | −0.19 (−1.67, 1.30); P = 0.806 | −6.47 | −0.80 (−2.29, 0.69); P = 0.292 |

| Nighttime maSBP | −10.06 | −13.40 | −3.34 (−5.63, −1.05); P = 0.004 | −13.71 | −3.65 (−5.95, −1.35); P = 0.002 |

| Nighttime maDBP | −5.41 | −7.39 | −1.98 (−3.46, −0.50); P = 0.009 | −7.57 | −2.16 (−3.64, −0.67); P = 0.005 |

| maPP | −4.58 | −5.78 | −1.20 (−1.83, −0.57); P < 0.001 | −5.98 | −1.40 (−2.03, −0.77); P < 0.001 |

BP, blood pressure; LSM, least squares mean; maDBP, mean ambulatory diastolic blood pressure; maPP, mean ambulatory pulse pressure; maSBP, mean ambulatory systolic blood pressure.

Data are LSM treatment difference (95% CI).

Compared with olmesartan, greater LSM reductions (95% CI) in 24‐hour maDBP were observed with sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg (P = 0.083) and 400 mg (P = 0.006) (Table 3). Both doses of sacubitril/valsartan provided significantly greater reductions in maPP than olmesartan (P < 0.001) (Table 3). Consistent with these observations, the Chinese subpopulation also showed greater reductions in 24‐hour maSBP, maDBP, and maPP with sacubitril/valsartan treatment (Supplementary Table 2).

All three treatment regimens decreased the daytime and nighttime ambulatory BP from baseline to Week 8. In particular, the reductions in nighttime maSBP and maDBP were significantly greater with both doses of sacubitril/valsartan compared with olmesartan 20 mg (Table 3). Similarly, in the Chinese subpopulation, reductions in nighttime maSBP and maDBP were significantly greater with sacubitril/valsartan compared with olmesartan 20 mg (Table S2).

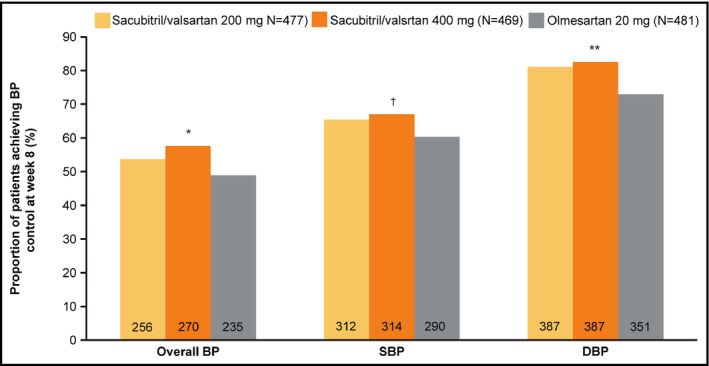

3.4. Blood pressure control

At Week 8, compared with olmesartan, a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved overall BP control (msSBP/msDBP <140/90 mm Hg), and SBP response with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg vs olmesartan (P = 0.006, Figure 3). A significantly greater percentage of patients achieved DBP response with both the doses of sacubitril/valsartan compared with the olmesartan 20 mg group (Figure 3). In addition, we also assessed the proportion of patients achieving BP control as defined by the recent ACC/AHA/ASH 2017 guidelines (msSBP/msDBP <130/80 mm Hg). Although the overall number of patients achieving these criteria was lower, a higher proportion of patients achieved BP control with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg (25.4%, P = 0.005) and sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg (20.5%, P = 0.303) vs olmesartan (17.9%).

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients achieving BP control, and SBP and DBP response rates at Week 8 endpoint. * P = 0.006, ** P = 0.002, † P = 0.032 for change vs. olmesartan 20 mg. BP control (msSBP/msDBP <140/90 mm Hg), SBP response (msSBP <140 mm Hg or a reduction from baseline >20 mm Hg), and DBP response (msDBP <90 mm Hg or a reduction from baseline >10 mm Hg). BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure

A similar trend was observed in the Chinese subpopulation.

3.5. Safety

In general, the safety profiles of sacubitril/valsartan and olmesartan were comparable. The frequency of treatment discontinuations due to AE was low at ~1% and comparable among all three groups. Most of the AEs were infrequent, mild/moderate, and transient in nature. Hyperlipidemia and hyperuricemia were the most common AEs with comparable incidence across the treatment groups (Table 4). The incidence of dizziness and cough was slightly higher in the sacubitril/valsartan treatment groups. Two events of confirmed angioedema were reported, one each in the sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg and olmesartan 20 mg groups. Both the events were mild in nature and resolved without hospitalization. The frequency of other clinically relevant AEs such as hyperkalemia and hypotension was generally low, of mild or moderate intensity, and similar in all three treatment groups.

Table 4.

Incidence of adverse events in ≥2% in any of the treatment groups (Safety set)

| Preferred term | Sacubitril/valsartan | Olmesartan | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

200 mg N = 478, n (%) |

400 mg N = 472, n (%) |

20 mg N = 484, n (%) |

|

| Any AEs | 143 (29.9) | 132 (28.0) | 134 (27.7) |

| AE discontinuations | 5 (1.0) | 4 (0.8) | 6 (1.2) |

| Discontinuations due to drug related AE | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| SAEs | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.6) | 6 (1.2) |

| Discontinuations due to SAEs | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.8) |

| Common AEsa | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 16 (3.3) | 22 (4.7) | 21(4.3) |

| Hyperuricemia | 14 (2.9) | 13 (2.8) | 16 (3.3) |

| Dizziness | 8 (1.7) | 11 (2.3) | 3 (0.6) |

| Increased blood glucose | 5 (1.0) | 10 (2.1) | 13 (2.7) |

| Cough | 11 (2.3) | 5 (1.1) | 3 (0.6) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 15 (3.1) | 5 (1.1) | 8 (1.7) |

| Headache | 6 (1.3) | 4 (0.8) | 10 (2.1) |

| Any SAEs | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.6) | 6 (1.2) |

| Gastroenteritis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Spinal osteoarthritis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.00 |

| Thyroid neoplasm | 0 (0.00 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0(0.0) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Angina pectoris | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Bile duct stone | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Calculus ureteric | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cholelithiasis | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pruritus | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Dengue fever | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Hypertension | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

AE, adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event.

AEs are sorted in descending frequency, as reported for sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg. A patient with multiple AEs within a primary system organ class is counted only once.

The incidence of SAEs was rare and similar in all the treatment groups (Table 4). No deaths were reported during the double‐blind treatment period.

4. DISCUSSION

This Phase III study showed that sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg was non‐inferior to olmesartan 20 mg in msSBP reduction and established the superiority of both doses of sacubitril/valsartan (200 mg and 400 mg) over olmesartan in reducing BP in Asian patients with hypertension, with the majority of the population being Chinese. Both doses of sacubitril/valsartan provided greater reductions from baseline in clinic and ambulatory SBP, DBP, and PP compared with olmesartan. Similar observations were also noted in the Chinese subgroup, demonstrating the efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan in this population. Notably, statistically significant and greater reductions in nighttime maSBP and maDBP were observed with sacubitril/valsartan treatments compared with olmesartan. In general, the safety and tolerability were comparable across the treatment groups.

Asian populations generally have a higher salt intake and are genetically more likely to have salt sensitivity than Western populations, making the management of hypertension challenging in this patient population.3, 16, 17 The detrimental effect of salt intake on BP is amplified by the increasing prevalence of obesity and other associated metabolic disorders.19, 20 It has been suggested that the BP‐lowering efficacy of monotherapy with renin‐angiotensin pathway inhibitors might be lower in Asians with salt‐sensitive hypertension and high salt intake.18 Studies in preclinical animal models indicate that the greater BP reductions achieved with sacubitril/valsartan compared with an ARB might be attributed to the enhancement of natriuretic peptides (NPs) due to neprilysin inhibition, resulting in increased urinary sodium excretion and inhibition of sympathetic activity.21 Given the higher prevalence of salt sensitivity in the Asian population, sacubitril/valsartan may be a suitable therapeutic option for treating hypertension. This is further supported by a recent study in Asian patients with salt‐sensitive hypertension, which showed superior BP control with sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan.22

Notably, this study found that nighttime BP reductions were prominently greater with sacubitril/valsartan than with olmesartan in Asian patients. This observation is consistent with the PARAMETER study showing greater reductions in nocturnal central aortic SBP and SBP with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg in elderly Caucasian patients compared with olmesartan 40 mg.12 Several studies have highlighted the impact of non‐reduction of nighttime BP in target organ damage and increased CV risk.23, 24 Therefore, nighttime BP is believed to be a better predictor of adverse CV outcomes than daytime BP.25 It has been suggested that salt‐restriction or decrease in the circulating volume by a diuretic can be employed to reduce nighttime BP and convert a non‐dipper to a dipper status.19, 26 The greater reductions in nighttime BP observed in this study could be attributed to increased NP‐mediated mechanism owing to neprilysin inhibition by sacubitril/valsartan. Considering the higher prevalence of non‐dippers among Asian patients and the strong correlation between nighttime BP and adverse CV risks,11, 27 our results suggest that treatment with sacubitril/valsartan is beneficial in Asian patient populations with hypertension, especially in the elderly. These findings confirm and extend those of a recent study in elderly Asian patients with hypertension demonstrating the safety and efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan.28

In this study, both doses of sacubitril/valsartan were effective in reducing PP compared with olmesartan. Elevated PP is an indicator of arterial stiffness and is a strong predictor of risk associated with adverse CV events such as stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure and CV disease, and mortality.29 Significantly greater reductions in PP with sacubitril/valsartan treatment, especially in the elderly patients, were also observed in previous studies.10, 11, 30

Finally, the reductions in msSBP and msDBP were greater than olmesartan in all the subgroups analyzed and were in line with overall study cohort. In particular, the reductions in clinic and ambulatory BP and PP in the Chinese subpopulation were in accordance with the overall study population, indicating the consistent efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan across various Asian patient subpopulations.11, 31, 32

The safety profile of sacubitril/valsartan reported in this study was comparable to that of olmesartan and in line with earlier reports.10, 11, 31

In addition to BP control, effective management of hypertension also focuses on prevention of target organ damage (including heart, kidney, and brain) and improving vascular function. The current study was primarily designed to evaluate the reductions in BP with sacubitril/valsartan treatment over 8 weeks. However, a recent study in hypertensive patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan 400 mg over a period of 52 weeks demonstrated clinically significant greater reductions in left ventricular mass (as assessed by cardiac MRI) compared to patients treated with olmesartan 40 mg. The greater reductions in left ventricular mass with sacubitril/valsartan treatment were apparent as early as Week 12. These observations indicate that clinical benefit of sacubitril/valsartan may go beyond its BP‐lowering action.33 In addition, sacubitril/valsartan treatment resulted in greater reductions in N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) and hs‐troponin than olmesartan and enalapril in the PARAMETER study with hypertensive patients and in the PARADIGM‐HF study with chronic heart failure patients, respectively.7, 12, 34 Sacubitril/valsartan has also been shown to decrease the rate of deterioration of renal function in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic kidney disease and/or diabetes.35, 36 These data provide additional support for the benefits of target end‐organ protection by neprilysin inhibition in patients with hypertension and/or other cardiovascular morbidities.

A potential limitation of the current study is that the dose of active comparator, olmesartan (20 mg/day), used is lower than the maximal approved dose of 40 mg/day in Western countries. The olmesartan 20 mg dose is a commonly prescribed daily dose in China and other Asian countries and has been previously used to evaluate its efficacy and safety in this population.13, 37, 38 Although olmesartan exhibits dose‐dependent decreases in BP up to 40 mg once daily, the incremental BP reduction was only modest comparing 40 mg vs 20 mg dose regimen. It is also important to note that the PARAMETER study, which compared sacubitril/valsartan (400 mg) to olmesartan (40 mg) in elderly patients with systolic hypertension and stiff arteries, has demonstrated the superiority of sacubitril/valsartan vs olmesartan 40 mg in reducing clinic and ambulatory central aortic and brachial pressures.12 In addition, the requirement of add‐on antihypertensive therapy was also lower in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan vs olmesartan.12

5. CONCLUSIONS

This 8‐week study showed that sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg and 400 mg once daily provided significantly greater BP reductions, particularly nighttime BP reductions, vs olmesartan 20 mg in Asian patients with mild‐to‐moderate systolic hypertension. All the study treatments are generally well tolerated. A pre‐specified subgroup analysis of the Chinese population also showed that sacubitril/valsartan was generally safe and efficacious for treating mild‐to‐moderate essential hypertension.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Y.H and W.L have received funding from Novartis Pharma AG for conducting this study. R.W, Q.W, L.Z, and W.G are employees of Novartis Pharma AG.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Nagabhushana Ananthamurthy, Dharman Vennila, and Sreedevi Boggarapu (Scientific Services, Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd, Hyderabad) for providing medical writing and editorial support.

Huo Y, Li W, Webb R, Zhao L, Wang Q, Guo W. Efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan compared with olmesartan in Asian patients with essential hypertension: A randomized, double‐blind, 8‐week study. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:67–76. 10.1111/jch.13437

Yong Huo and Weimin Li have contributed equally to this work.

Funding information

This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG. Y.H and W.L have received funding from Novartis Pharma AG for conducting this study. R.W, Q.W, L.Z, and W.G are employees of Novartis Pharma AG.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Law MR, Elliott P, MacMahon S, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and the global burden of disease 2000. Part 1: estimates of blood pressure levels. J Hypertens. 2006; 24(3):413‐422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Parag V, et al. Asia Pacific Cohort Studies C. Blood pressure indices and cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific region: a pooled analysis. Hypertension. 2003;42(1):69‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park JB, Kario K, Wang JG. Systolic hypertension: an increasing clinical challenge in Asia. Hypertens Res. 2015;38(4):227‐236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ueshima H, Sekikawa A, Miura K, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in Asia: a selected review. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2702‐2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perkovic V, Huxley R, Wu Y, Prabhakaran D, MacMahon S. The burden of blood pressure‐related disease: a neglected priority for global health. Hypertension. 2007;50(6):991‐997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chalmers J. Hypertension guidelines: timely new initiatives from East Asia. Pulse (Basel). 2015;3(1):1‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993‐1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Novartis . Entresto™ (sacubitril and valsartan): US prescribing information. 2015. http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/entresto.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2018.

- 9. Hubers SA, Brown NJ. Combined angiotensin receptor antagonism and neprilysin inhibition. Circulation. 2016;133(11):1115‐1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ruilope LM, Dukat A, Bohm M, Lacourciere Y, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP. Blood‐pressure reduction with LCZ696, a novel dual‐acting inhibitor of the angiotensin II receptor and neprilysin: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, active comparator study. Lancet. 2010;375(9722):1255‐1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kario K, Sun N, Chiang FT, et al. Efficacy and safety of LCZ696, a first‐in‐class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, in Asian patients with hypertension: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Hypertension. 2014;63(4):698‐705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams B, Cockcroft JR, Kario K, et al. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan versus olmesartan on central hemodynamics in the elderly with systolic hypertension: the PARAMETER study. Hypertension. 2017;69(3):411‐420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu LS, Writing Group of Chinese Guidelines for the Management of H . 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011;39(7):579‐615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Izzo JL Jr, Zappe DH, Jia Y, Hafeez K, Zhang J. Efficacy and safety of crystalline valsartan/sacubitril (LCZ696) compared with placebo and combinations of free valsartan and sacubitril in patients with systolic hypertension: the RATIO study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2017;69(6):374‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a Report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269‐1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stamler J. The INTERSALT Study: background, methods, findings, and implications. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1997;65(2 Suppl):626S‐642S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Katsuya T, Ishikawa K, Sugimoto K, Rakugi H, Ogihara T. Salt sensitivity of Japanese from the viewpoint of gene polymorphism. Hypertens Res. 2003;26(7):521‐525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang JG, Kario K, Lau T, et al. Use of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in the management of hypertension in Eastern Asians: a scientific statement from the Asian Pacific heart association. Hypertens Res. 2011;34(4):423‐430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uzu T, Kimura G, Yamauchi A, et al. Enhanced sodium sensitivity and disturbed circadian rhythm of blood pressure in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 2006;24(8):1627‐1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen J, Gu D, Huang J, et al. Metabolic syndrome and salt sensitivity of blood pressure in non‐diabetic people in China: a dietary intervention study. Lancet. 2009;373(9666):829‐835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kusaka H, Sueta D, Koibuchi N, et al. LCZ696, angiotensin II receptor‐neprilysin inhibitor, ameliorates high‐salt‐induced hypertension and cardiovascular injury more than valsartan alone. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(12):1409‐1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang TD, Tan RS, Lee HY, et al. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) on natriuresis, diuresis, blood pressures, and NT‐proBNP in salt‐sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2017;69(1):32‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the european society of hypertension (ESH) and of the european society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34(28):2159‐2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sarigianni M, Dimitrakopoulos K, Tsapas A. Non‐dipping status in arterial hypertension: an overview. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2014;12(3):527‐536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boggia J, Li Y, Thijs L, et al. Prognostic accuracy of day versus night ambulatory blood pressure: a cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370(9594):1219‐1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uzu T, Kimura G. Diuretics shift circadian rhythm of blood pressure from nondipper to dipper in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1999;100(15):1635‐1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Y, Wang JG, Gao P, et al. Are published characteristics of the ambulatory blood pressure generalizable to rural Chinese? The JingNing population study. Blood press Monit. 2005;10(3):125‐134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Supasyndh O, Wang J, Hafeez K, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Rakugi H. Efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) compared with olmesartan in elderly Asian patients (>/=65 years) With systolic hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30(12):1163‐1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Safar ME. Systolic blood pressure, pulse pressure and arterial stiffness as cardiovascular risk factors. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10(2):257‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rakugi H, Kario K, Yamaguchi M, Thompson S, Gotou H, Zhang J. Efficacy and safety of LCZ696 compared with olmesartan in Japanese patients with systolic hypertension. 68th High Blood Pressure Research Conference.2014.

- 31. Supasyndh O, Sun N, Kario K, Hafeez K, Zhang J. Long‐term (52‐week) safety and efficacy of Sacubitril/valsartan in Asian patients with hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2017;40(5):472‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang JG, Yukisada K, Sibulo A Jr, Hafeez K, Jia Y, Zhang J. Efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) add‐on to amlodipine in Asian patients with systolic hypertension uncontrolled with amlodipine monotherapy. J Hypertens. 2017;35(4):877‐885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schmieder RE, Wagner F, Mayr M, et al. The effect of sacubitril/valsartan compared to olmesartan on cardiovascular remodelling in subjects with essential hypertension: the results of a randomized, double‐blind, active‐controlled study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(44):3308‐3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2015;131(1):54‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Damman K, Gori M, Claggett B, et al. Renal effects and associated outcomes during angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(6):489‐498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Packer M, Claggett B, Lefkowitz MP, et al. Effect of neprilysin inhibition on renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic heart failure who are receiving target doses of inhibitors of the renin‐angiotensin system: a secondary analysis of the PARADIGM‐HF trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(7):547‐554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu JR, Cai NS, Fan WH, et al. Efficacy and safety of olmesartan medoxomil versus losartan potassium in Chinese patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2006;34(10):877‐881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liau CS, Lee CM, Sheu SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of olmesartan in the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate essential hypertension in Chinese patients. Clin Drug Investig. 2005;25(7):473‐479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials