Abstract

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2010 study estimated national salt intake for 187 countries based on data available up to 2010. The purpose of this review was to identify studies that have measured salt intake in a nationally representative population using the 24‐hour urine collection method since 2010, with a view to updating evidence on population salt intake globally. Studies published from January 2011 to September 2018 were searched for from MEDLINE, Scopus, and Embase databases using relevant terms. Studies that provided nationally representative estimates of salt intake among the healthy adult population based on the 24‐hour urine collection were included. Measured salt intake was extracted and compared with the GBD estimates. Of the 115 identified studies assessed for eligibility, 13 studies were included: Four studies were from Europe, and one each from the United States, Canada, Benin, India, Samoa, Fiji, Barbados, Australia, and New Zealand. Mean daily salt intake ranged from 6.75 g/d in Barbados to 10.66 g/d in Portugal. Measured mean population salt intake in Italy, England, Canada, and Barbados was lower, and in Fiji, Samoa, and Benin was higher, in recent surveys compared to the GBD 2010 estimates. Despite global targets to reduce population salt intake, only 13 countries have published nationally representative salt intake data since the GBD 2010 study. In all countries, salt intake levels remain higher than the World Health Organization's recommendation, highlighting the need for additional global efforts to lower salt intake and monitor salt reduction strategies.

Keywords: evidence, global burden of disease, global targets, salt intake estimates, sodium

1. INTRODUCTION

High dietary salt intake is associated with increased blood pressure, a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and several studies have shown that low salt intake decreases both blood pressure and the incidence of CVD.1 Globally, 1.65 million deaths from CVD each year are attributed to salt consumption above the World Health Organization's recommended daily intake of <5 grams per day (g/d),2 and the current daily mean population salt consumption in most countries far exceeds this recommendation.3 The most recent Global Burden of Disease study reported that high intake of sodium was the leading dietary risk factor of mortality, accounting for 3.20 million deaths globally in 2017.4

The 2010 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factor Study (hereinafter referred to as GBD 2010) quantified global, regional, and country‐specific estimates of salt intake for 187 countries in 1990 and 2010. This was based on surveys in 66 countries using 24‐hour urine collection method (n = 142) and dietary reporting method (n = 103) including diet recall, diet record, food frequency questionnaires, and household availability/budget survey. Bayesian hierarchical modeling used all available data to estimate salt intake by age, sex, and time for 187 countries. The study found that global mean salt intake in 2010 was 10.06 g/d (95% uncertainty interval 9.88‐10.21). Estimated mean salt intakes in 181 of 187 countries exceeded the WHO recommendation. Around 119 countries exceeded the recommended amount by at least 2.5 g salt/d and 51 countries were estimated to be consuming more than double the recommended level.5

A number of different methods can be used to assess dietary salt intake but when rigorously performed the 24‐hour urine collection method is regarded as the gold standard method for estimating individual or population salt intake. A 24‐hour urine collection is recommended for assessing mean sodium intake since on average 93% of sodium is excreted through kidneys and provide an estimate of total sodium intake from all sources.6 At the individual level, dietary reporting methods such as 24‐hour dietary recall or food frequency questionnaires may under‐ or over‐estimate salt intake.7 Timed spot urine samples have been proposed by some researchers as an alternative approach, but it is currently unknown whether this approach provides the level of accuracy required for measuring change over time. In fact, population mean sodium estimates are overestimated at lower 24‐hour urine sodium consumption and underestimated at higher sodium consumption raising concerns that spot urine methods may be inappropriate to track changes in dietary sodium in unpaired data.8 Therefore, 24‐hour urine collection is considered the optimal method.6

WHO Member States agreed to a 30% interim reduction in mean population salt intake by 2025,9 and a 2014 review identified national salt reduction strategies in 75 countries. However, these countries, and numerous others without strategies, have not undertaken a robust assessment of population salt intake from which to measure any future change.10 GBD 2010 provided baseline estimates for mean population salt intake for each country. The objective of this review was therefore to identify nationally representative studies that have assessed salt intake among adult populations based upon the 24‐hour urine collection between January 2011 and September 2018. This was with a view to comparing with GBD 2010 estimates to update existing population salt intake estimates globally.

2. METHODS

The present review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.11 A systematic search for original research papers that were published from January 2011 to September 2018 was conducted in MEDLINE, Scopus and Embase databases using the keywords: “sodium, Na, sodium chloride, salt” in combination with “intake, ingest, eat, consume, diet, urine, excretion.” In addition, relevant published papers were searched from the weekly Science of Salt eNewsletter publication.12 The Science of Salt Weekly is a publication of weekly Medline searches related to dietary sodium.13 Reference lists and bibliographies of articles were reviewed manually from relevant articles. The study protocol is registered with PROSPERO, number CRD42015026604.

Studies of healthy/general adult populations older than 18 years that assessed dietary salt intake using the 24‐hour urine collection method and could be used as the basis of national estimates were included. Studies were excluded if (a) salt intake was assessed in a sample population that was not nationally representative or that could not be extrapolated to a national‐level (b) assessment of salt intake was based on dietary reporting method or urinary collections that were for less than 24 hours, such as spot urine collection (c) if the study population was a specific group such as pregnant women, children, adolescents, elderly participants, or those with cardiovascular or renal disease, hypertension, diabetes, thyroid disorders and (d) study data were included in GBD 2010.

All search results were exported into EndNote, and duplicates were removed. Two reviewers (ST, JS) independently assessed and reviewed the titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full‐text articles from the abstracts that met the inclusion criteria were then reviewed. An Excel data extraction template was developed to collect the following information: study details (title, author, name of the study, years of study, country location), study design, study population (age and sex), sample size (number of participants included and recruited), criteria for 24‐hour urine collection (criteria specific measurement, number that did not meet criteria, number with complete 24‐hour urine, number of days of urine collection), data collection period, and salt intake estimates (overall and by sex, if reported). Any discrepancies in study assessment and data extraction were resolved through a consensus discussion with a third reviewer (BM). From the countries identified in the search, data were extracted from the GBD database to obtain 2010 salt intake estimates (overall and by sex).

The primary outcome was the overall mean population salt intake. Secondary outcomes were mean difference in salt intake estimates between recent studies published between January 2011 and September 2018 and GBD 2010. We reported the number of participants, mean, and 95% confidence interval (CI) from each of the studies identified between January 2011 and September 2018. For consistency in reporting, we converted all estimates to salt intake in g salt/d using the formula: 1 mmol of sodium = 23 mg; 1000 mg (1 g) sodium = 2.54 g salt.14 We converted standard deviations or standard errors to 95% confidence intervals following the equations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.15 For studies that only reported salt intake estimates in subgroups (eg by sex), we combined the estimates following the equations in the Cochrane Handbook, where applicable. For countries with multiple studies available between 2011 and 2018, we have included the study with the most recent data in the analysis. Further, for studies with multiple data points,16, 17 we have used the last data point reported.

We determined the difference between the mean salt intake measured from the 24‐hour urine collection and the estimated salt intake from GBD 2010. We considered a difference in mean salt intake of <1 g/d as slight difference, 1‐2 g/d as moderate difference, and >2 g/d as substantial difference.18

3. RESULTS

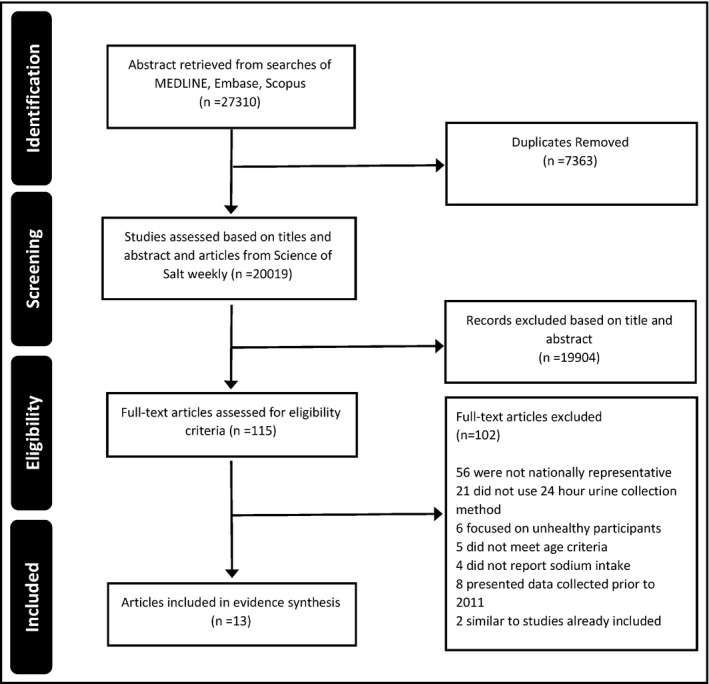

A total of 27 310 studies were retrieved by searching the MEDLINE, Scopus, and Embase databases, of which 7363 duplicates were removed (Figure 1). After title and abstract screening of 20 019 studies including articles from Science of Salt weekly (n = 72), a further 19 904 articles were excluded, leaving 115 potentially relevant articles for full‐text review. Of the 115 articles, thirteen studies that were conducted between 2011 and 2018 met the inclusion criteria, and captured data on 11 656 participants. Studies were excluded because they were not based on a nationally representative sample (n = 56); did not use 24‐hour urine collection (n = 21); focused on specific population groups (n = 6); did not meet the age criteria (n = 5); did not report salt intake (n = 4); presented data collected prior to 2011 (n = 8); and already included in the GBD 2010 (n = 2).

Figure 1.

Studies included in current review, January 2011–September 2018

3.1. Description of studies

Four of the studies were from low‐ and middle‐income countries (Fiji, Benin, Samoa and India) and nine are from high‐income countries (Italy, Portugal, Switzerland, England, Canada, the United States, Barbados, Australia, and New Zealand) (Table 1). Sample sizes ranged from 272 in Fiji to 2578 in Portugal. The proportion of males and females were nearly equal across all studies, and age ranged between 18 and 90 years. The majority of studies used 24‐hour urine volume and creatinine to assess the completeness of 24‐hour urine collection16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27; while two studies used para‐amino benzoic acid (PABA).28, 29 Details on the representativeness of each study are presented in Table 1 (with references).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies on national sodium (salt) intake undertaken between 2011 and 2018

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | Age (y), mean ± SD or range | % Males | Criteria for 24 h urine completeness | N didn't meet criteria | Final sample size | Notes on representativeness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |||||||||

| Donfrancesco et al, 201319 | 2013 | Italy | Secondary analysis of cross‐sectional data from OEC/HES | 57 ± 12 | 50 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU volume was <500 mL or creatinine content referred to body weight was <2SD from the population mean |

T: 68 M: 54 F: 14 |

2212 | 1114 | 1098 | Random sample of adults (age‐ and sex‐stratified) from 12 Italian regions.a |

| Polonia et al, 201420 | 2014 | Portugal | Cross‐sectional | 18‐90 | 48 | Samples were considered valid if 24 HU creatinine/kg of weight was between 18.5 and 25.0 mg/kg (M 18‐50 y), 15.7 and 20.2 mg/kg (M 51‐75), 16.5 and 22.4 mg/kg (F 18‐50), and 11.8 and 16.1 mg/kg (F 51‐75) | T: 414 | 2578 | 1234 | 1344 | Multi‐stage cluster random (age‐ and sex‐stratified) sampling was used to select a sample representative of the 18‐90‐y‐old population. |

| Ogna et al, 201421 | 2014 | Switzerland | Secondary analysis of cross‐sectional data from the Swiss Survey on Salt | 47 ± 18 | 48 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU volume was <300 mL or if subjects reported not having collected all 24 HU | T: 3 | 1505 | 725 | 780 | Data were from the Swiss Salt Survey, a nationwide survey of adults aged 15 y and over. A two‐level random sampling strategy was used (age‐ and sex‐stratified). Convenience sampling was conducted in selected centers due to difficulties in recruiting young participants.a |

| He et al, 201428 | 2014 | England | Secondary analysis of cross‐sectional data from NDNS and sodium boost studyb | 19‐64 | 46 | Completeness was assessed using para‐aminobenzoic acid (PABA): samples were considered complete if PABA recovery was between 70% and 104% |

T: 166 M: 59 F: 107 |

547 | 250 | 297 | The surveys were conducted to collect representative sample of the population aged 19‐64 y living in private households. Weights were applied to account for unequal selection probabilities of individuals within households and for non‐response.b |

| Mente et al, 201629 | 2015 | Canada | Secondary analysis of data from the PURE study | 59.6 ± 9.0, 37‐72 | 49 | 1. Samples were considered valid if 24 HU creatinine was within 8.8‐22 mmol (995‐2489 mg) for men and 4.5‐16 mmol (509‐1810 mg) for women | T: 100 | 1600 | NR | NR | Sampling strategy used in the PURE study was intended to collect representative sample of the population |

| 2. Completeness was assessed using para‐aminobenzoic acid (PABA): samples were considered complete if PABA recovery was between 70% and 110% (among PABA eligible: <65 y) | T: 102 | 848 | NR | NR | NOTE: Salt intake estimates from using both criteria were used. | ||||||

| McLean et al, 201522 | 2015 | New Zealand | Cross‐sectional | 18‐64 | 48 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU volume was <500 mL or 24 HU creatinine was <60% of the estimated value or if participant reported missing two or more voids | T: 2 | 299 | 145 | 154 | Random sample of adults in two cities through the New Zealand electoral roll. Snowball sampling was used to recruit further 18‐24‐y‐old men. Data were weighted based on population estimates by age and sex from the 2012 New Zealand Census.a NOTE: Weighted estimates were used |

| Mizehoun‐Adissoda et al, 201723 | 2017 | Benin | Cross‐sectional | 43.0 ± 11.3, 25‐64 | 49 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU volume was <500 mL or 24 HU creatinine was <10 mg/kg body weight for women and <15 mg/kg body weight for men | T: 30 | 354 | 172 | 182 | Cluster sampling technique with probability proportional to size was used. Selected individuals were representative of the population |

| Johnson et al, 201724 | 2017 | India | Cross‐sectional | 20 and above | 50 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU volume was <500 mL; 24 HU creatinine was <6 mmol for men or <4 mmol for women; duration of collection was <24 h; >1 missed void; and >1 episode of significant spillage | T: 438 | 957 | 475 | 482 | Age‐ and sex‐stratified sampling strategy in rural, urban and slum areas. Analysis accounted for survey weights, strata and clustering in the study design.a |

| Pillay et al, 201716 | 2017 | Fiji | Cross‐sectional | 42.4 ± 0.6, 25‐64 | 46 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU volume was <500 mL or 24 HU creatinine was <4 mmol in women and <6 mmol in men | T: 166 | 272 | 126 | 146 |

Multi‐stage cluster sampling procedure was applied to select representative sample of the adult population. Data were weighted based on the sex, age and ethnicity distribution of the 2007 Fiji census NOTE: Follow‐up salt intake estimates were used |

| Santos et al, 201725 | 2017 | Australia | Cross‐sectional | 58, 20 and above | 44 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU creatinine was <4 mmol in women and <6 mmol in men; a 24 HU volume was <500 mL or extreme outliers for urinary creatinine (ie >3 standard deviation from the mean) | T: 25 | 412 | 183 | 229 | Combined sample of randomly‐selected individuals and volunteer samples. Data were age‐ and sex‐weighted according to the 2011 census data of Australia |

| Cogswell et al, 201826 | 2018 | United States | Cross‐sectional (conducted as part of the United States NHANES) | 20‐69 | 51 | Samples were considered complete if: collection start and end time was recorded; collection duration was ≥22 h; 24 HU volume was ≥500 mL; participant reported that no more than a few drops of urine were missed; and for women, not menstruating during the collection | T: 67 | 827 | 421 | 406 |

The study was part of NHANES 2014, a nationally representative survey of the United States civilian non‐institutionalized population NOTE: Salt intake estimates from the first collection were used |

| Harris et al, 201827 | 2018 | Barbados | Cross‐sectional | 25 and above | 44 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU volume was <500 mL or >5000 mL, timing of collection fell outside the 20‐28 h period or the participant reported missing more than one urine void; 24 HU creatinine was <4 mmol in women and <6 mmol in men | T: 4 | 364 | 161 | 203 | Multi‐stage probability sampling procedure was applied to select representative sample of the adult population. Data were weighted based on the sex and age distribution of the 2010 census data of Barbados |

| Trieu et al, 201817 | 2018 | Samoa | Cross‐sectional | 37.4 ± 0.7, 18‐64 | 47 | Samples were excluded if 24 HU volume was <500 mL or 24 HU creatinine was <4 mmol or >25 mmol in women and <6 mmol or >30 mmol in men | T: 161 | 481 | 226 | 255 |

Three‐stage multi‐cluster sampling procedure was applied to select representative sample of the adult population. Data were weighted based on the sex, age and area distribution of the 2011 Samoa census NOTE: Follow‐up salt intake estimates were used. Weighted estimates used, not the raked estimates |

Abbreviations: 24 HU, 24 h urine; F, female; M, male; NDNS, National Diet and Nutrition Survey; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NR, not reported or unable to be derived based on data reported; OEC/HES, Cardiovascular Epidemiology Observatory/Health Examination Survey; PURE, Prospective and Urban Rural Epidemiology; T, total; WHO STEPS, World Health Organization STEPwise approach to surveillance of non‐communicable disease risk factors.

Higgins J & Green S (2008). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Sadler K, Nicholson S, Steer T, et al (2011). National Diet and Nutrition Survey – Assessment of dietary sodium in adults (aged 19‐64 y) in England, 2011. A survey carried out on behalf of the Department of Health.

Based on creatinine excretion.

Based on PABA recovery.

3.1.1. Recent salt intakes

The salt intake in the identified studies published between January 2011 and September 2018 ranged from 6.75 g/d (6.32‐7.17) in Barbados to 10.66 g/d (10.52‐10.81) in Portugal. All salt intake levels are higher than the WHO‐recommended maximum consumption level of 5 g/d (Table 2).

Table 2.

Salt intake estimates from GBD study 2010 and studies published between January 2011 and September 2018

| Country | Salt intake estimates (g/d) from studies published between January 2011 and May 2017 | Salt intake estimates (g/d) from the GBD 2010 modeling study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection period | Overall | Male | Female | Data source | Overall | Male | Female | |

| Italy19 | 2008‐2012 | 9.82 (9.66‐9.98) | 11.04 (10.81‐11.28) | 8.59 (8.35‐8.76) | 7 surveys44, 45, 46, 47 between 1986 and 2003: 5U, 2D | 11.23 (10.72‐11.71) | 11.81 (11.02‐12.60) | 10.64 (9.96‐11.30) |

| Portugal20 | NOV‐2011 to DEC‐2012 | 10.66 (10.52‐10.81) | 10.84 (10.63‐11.06) | 10.40 (10.20‐10.59) | 3 surveys44, 48, 49 between 1986 and 2003: 2U, 1D | 10.77 (10.11‐11.46) | 11.33 (10.34‐12.42) | 10.24 (9.35‐11.20) |

| Switzerland21 | JAN‐2010 to MAR‐2012 | 9.14 (8.96‐9.33) | 10.60 (10.32‐10.87) | 7.79 (7.59‐8.00) | 1 survey50 in 2010: 1U | 9.17 (8.64‐9.78) | 9.65 (8.84‐10.49) | 8.69 (7.95‐9.50) |

| England28 |

NDNS: JUL‐2011 to DEC‐2011 Sodium boost: SEP‐201 to DEC‐2011 |

8.06 (7.58‐8.55) | 9.29 (8.57‐10.01) | 6.84 (6.43‐7.24) | 16 surveys44, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 between 1985 and 2009: 9U, 3D, 4B | 9.17 (8.76‐9.60) | 9.65 (9.07‐10.29) | 8.69 (8.18‐9.22) |

| Canada29 | JAN‐2012 to DEC‐2013 | Criteria 1:a 8.22 (8.04‐8.39) | 9.56 (9.30‐9.82) | 6.98 (6.79‐7.17) | 5 surveys 44, 61, 62, 63, 64 between 1986 and 2004: 2U, 3D | 9.42 (9.09‐9.73) | 9.86 (9.37‐10.36) | 8.97 (8.53‐9.40) |

| Criteria 2:b 8.82 (8.56‐9.08) | 10.23 (9.83‐10.63) | 7.53 (7.24‐7.81) | ||||||

| New Zealand22 | FEB‐2012 to NOV‐2012 | 8.58 (8.13‐9.02) | 9.79 (9.14‐10.44) | 7.43 (6.90‐7.97) | 3 surveys65, 66, 67 between 1981 and 1997: 2U, 1D | 8.81 (8.46‐9.22) | 9.27 (8.71‐9.88) | 8.41 (7.90‐8.92) |

| Benin23 | NOV‐2012 to SEP‐2013 | 10.20 (9.69‐10.71) | 10.33 (9.56‐11.10) | 10.18 (9.47‐10.89) | 1 survey68 in 1996: 1U | 7.24 (6.32‐8.18) | 7.54 (6.27‐8.94) | 6.93 (5.79‐8.26) |

| India24 | FEB‐2014 to JUN‐2014 | 9.08 (8.62‐9.54) | 9.73 (9/08‐10.39) | 8.33 (7.70‐8.96) | 6 surveys44, 69, 70, 71, 72 between 1986 and 2005: 2U, 4D | 9.45 (9.22‐9.70) | 9.86 (9.47‐10.21) | 9.04 (8.74‐9.35) |

| Fiji16 | AUG‐2012 to DEC‐2013 | 10.29 (9.27‐11.30) | 11.28 (9.96‐12.61) | 9.24 (8.04‐10.46) | Data source was not presented in GBD 2010 | 7.29 (6.12‐8.66) | 7.67 (5.99‐9.75) | 6.96 (5.41‐8.71) |

| Australia25 | 2011 | 9.04 (8.58‐9.49) | 10.31 (9.54‐11.09) | 7.80 (7.30‐8.30) | 6 surveys73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78 between 1989 and 2011: 6U | 8.69 (8.36‐9.02) | 9.12 (8.61‐9.58) | 8.28 (7.85‐8.69) |

| United States26 | 2014 | 9.16 (8.67‐9.66) | 10.68 (10.06‐11.31) | 7.72 (7.22‐8.21) | 20 surveys44, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83 between 1981 and 2005: 9U, 1D, 10B | 9.14 (8.89‐9.40) | 9.60 (9.22‐9.98) | 8.71 (8.36‐9.04) |

| Barbados27 | JUNE‐2012 to NOV‐2013 | 6.75 (6.32‐7.17) | 7.31 (6.77‐7.84) | 6.23 (5.58‐6.88) | 2 surveys80, 84 between 1992 and 2005: 1U, 1D | 8.69 (7.90‐9.55) | 9.12 (7.92‐10.39) | 8.26 (7.24‐9.37) |

| Samoa17 | MAR‐2013 to MAY‐2013 | 7.65 (7.22‐8.07) | 7.98 (7.41‐8.50) | 7.28 (6.66‐7.91) | 1 survey85 in 1991: 1D | 5.26 (4.62‐5.94) | 5.49 (4.62‐6.53) | 5.00 (4.22‐5.89) |

Abbreviations: B, both urine‐ and diet‐based; D, diet‐based; NDNS, National Diet and Nutrition Survey; NR, Not reported or unable to be computed based on data reported; SE, Standard Error; U, urine‐based.

Based on creatinine excretion.

Based on PABA recover.

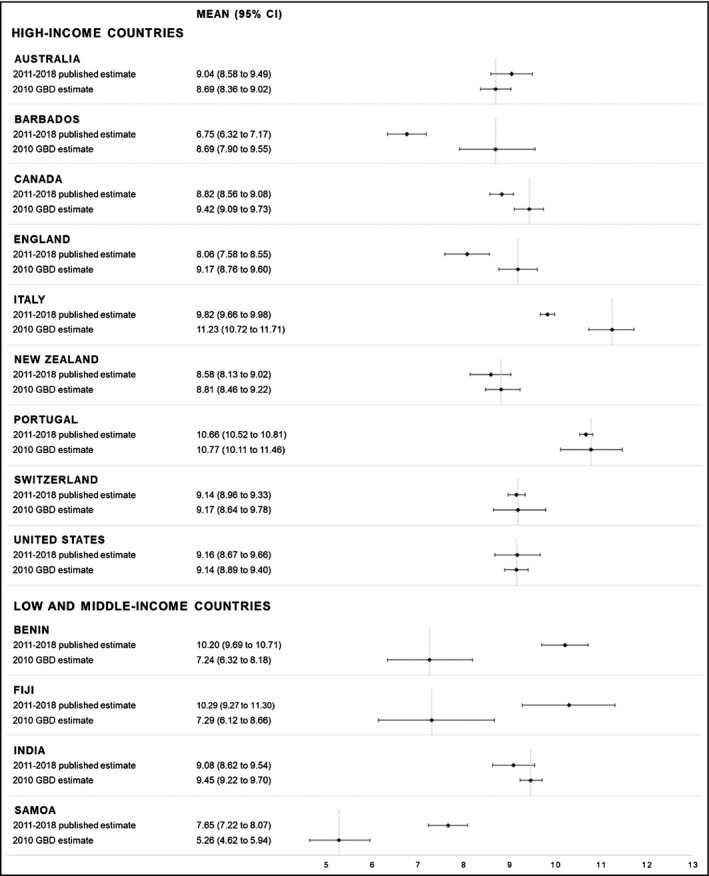

3.1.2. Comparison with estimates of GBD 2010

For seven countries, recent measured mean population salt intake differed from the GBD 2010 (Figure 2 and Table 2). Mean salt intake from recent surveys was slightly lower in Canada (mean difference: −0.6 g/d), and moderately lower in Barbados (−1.94 g/d), England (−1.11 g/d), and Italy (−1.41 g/d), compared to GBD 2010. On the other hand, in three low‐ to middle‐income counties, mean salt intake from recent surveys was substantially higher in Benin (2.96 g/d), Fiji (3 g/d), and Samoa (2.39 g/d), compared to GBD 2010. The salt intake estimates from the remaining six countries (Australia, India, New Zealand, Portugal, Switzerland, and the United States) were similar between recent studies and GBD 2010.

Figure 2.

Graph by income

4. DISCUSSION

This review identified 13 nationally representative studies from 13 different countries which have assessed salt intake estimates using the gold standard 24‐hour urine collection method, since the GBD 2010. Salt intake levels in all countries exceeded the WHO‐recommended level of 5 g salt/d which highlights the need for continued salt reduction programmes.

In the present review, Italy, England, Canada, and Barbados had lower salt intakes in recent surveys than previous GBD 2010 estimates. It is not possible to know whether these findings reflect true reductions in salt intake as a result of programmes to reduce salt or if they are due to different sampling or salt measurement approaches as many of the GBD estimates were based on imputation of different sources. However, it should be noted that these four countries have been implementing salt reduction strategies.10 Italy has established a programme to work with the food industry including legislation to limit the salt content of bread.30 England has been implementing a comprehensive government lead, salt reduction intervention including salt targets and working with industry to reformulate foods since 2006.31 Canada has also established targets for packaged foods that contribute the most salt to the Canadian diet.32 Similarly, Barbados has set targets to reduce salt contents in foods and held a series of meetings with the food industry.33 Therefore, our findings are consistent with reductions in population salt intake may have occurred since GBD 2010.

Fiji, Benin, and Samoa had higher population salt intakes in recent surveys compared to those reported through the GBD 2010. Again, this may reflect a true increase in salt intake or be a result of different approaches to measurement. In the GBD 2010, the estimated levels of sodium excretion for all country‐time periods were considered by specifying an age‐integrating Bayesian hierarchical model using as a parent model, DisMod‐MR The model was used to estimate fixed effects for study‐specific and national‐level covariates, and random effects for GBD super region, region, and country.5 Many low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) including Fiji, Benin, and Samoa have been experiencing a nutrition transition, changing consumption pattern away from traditional foods to processed and packaged foods, which may have potentially contributed to increasing salt intake over the last few years.34, 35

Adoption of population salt reduction strategies is slow in LMICs and remains a challenge as these countries are experiencing a double burden of communicable and non‐communicable diseases, competing health priorities and limited resources for health.36 However, population salt reduction initiatives including food reformulation, consumer education, front of pack labeling, and interventions in public institutions are being implemented in some countries.10 Additionally, salt reduction strategies need to have high‐level commitment across government departments in conjunction with the establishment of a national‐level mechanism to monitor salt intake.

Measurement of the 24‐hour urine collection is considered the “gold standard” to estimate dietary salt intake with standard criteria for completeness of the specimens varying from most using urine volume and creatinine and some using PABA.37, 38 For this review, we therefore decided to include only those studies that had estimated salt intake using 24‐hour urine samples. Several large scale population studies have assessed salt intake by the 24‐hour urine collection in multiple countries. INTERSALT (1985‐87) obtained 24‐hour urine sample collections from 52 population samples across 32 countries.39 INTERMAP included four 24‐hour dietary recalls and two timed 24‐hour urine samples from 17 population samples from four countries.40 Both of these studies demonstrate that collecting nationally representative samples of 24‐hour urine collections in large‐scale epidemiological studies is feasible. However, other research has highlighted that collecting 24‐hour urine collections is burdensome to participants,41 so spot urine collections are increasingly being used as a convenient and affordable alternative for estimating population salt intake. However, while some studies have shown that spot urine samples can provide a reasonable estimate of population‐level salt intake,8 there is not sufficient evidence to show whether this can be replicated in all population groups.42 Therefore, there are recommended against using spot urine collections,43 which is why we limited this review to studies that had used 24‐hour urine samples.

This review is the first to compare recent salt intake measurements to those derived from the estimates in the GBD study 2010. A key strength is that it included a comprehensive systematic search of the peer‐reviewed articles on population salt intake where the sample frame was nationally representative from three databases. We systematically identified and extracted data as per pre‐defined inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. A further strength is that it only included those studies that used the 24‐hour urine collection method, and therefore only salt intake estimates from the current gold standard were used. Several methods were used to assess the completeness of 24‐hour urine collection in the included studies. Only two studies used PABA (generally considered as gold standard) and the rest used creatinine/volume criteria (and use of these criteria differed across the studies) on the completeness of collection of the 24‐hour urines. A limitation of the review is that it relied only on the published literature so it does not capture countries that have measured salt intake but have not published the results in peer‐reviewed literature. We also only included studies that had broadly representative sample of the healthy populations and not studies of specific population groups, but this was important to be able to compare to the GBD 2010. The salt intake estimates in the GBD 2010 were based on Bayesian hierarchical modeling which used survey data and their characteristics to estimate mean sodium intake, by age and sex for 187 countries. It is therefore not possible to know whether some new estimates are different because population salt intake has changed or the differences are due to the methods used.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, only 13 countries have published nationally representative salt intake data using the 24‐hour urine collection method since 2010. Whilst it is not possible to be sure whether differences in salt intake between the new studies and the GBD estimates reflect changes in salt intake or are due to differences in methodological approaches, salt intake levels in all countries remain higher than WHO‐recommended levels. Thus, there is an urgent need for national public health policies focused on reducing salt intake including additional global efforts to lower salt intake and monitor salt strategies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

JW is the Director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre on Population Salt Reduction and is supported by a National Heart Foundation Future Leaders Fellowship Level II (App: 102039). JW has funding from WHO, the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (Grant/Award Number: 20122) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia for research on salt reduction (Grant/Award Numbers: App: 1052555 and App: 1111457). KT is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia early career fellowship (App: 1161597) and the National Heart Foundation of Australia Postdoctoral Fellowship (Award ID 102140). NRCC was a paid consultant to the Novartis Foundation (2016‐2017) to support their programme to improve hypertension control in low‐ to middle‐income countries which includes travel support for site visits and a contract to develop a survey. NRCC has provided paid consultative advice on accurate blood pressure assessment to Midway Corporation (2017) and is an unpaid member of World Action on Salt and Health (WASH). Of the studies reviewed, JW, KT, and JS were an author on Johnson C et al (2017), Pillay A et al (2017), Santos JA et al (2017), and Trieu K et al (2018). ST, JS, BM, KT, CJ, RM, and JA have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ST, JS, KT, and JW conceived the study. JS and BM conducted the search from databases. ST and JS did the screening of articles. ST and JS did the analysis and interpretation. TS wrote the first draft of the paper. JS, BM, KT, CJ, RM, JA, NRCC, and JW provided comments on the drafts and approved the final paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The process to provide regular updates on the science of sodium is supported by: the World Hypertension League, WHO Collaborating Centre on Population Salt Reduction (The George Institute for Global Health), Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) Technical Advisory Group on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention through Dietary Sodium and World Action on Salt and Health.

Thout SR, Santos JA, McKenzie B, et al. The Science of Salt: Updating the evidence on global estimates of salt intake. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:710–721. 10.1111/jch.13546

REFERENCES

- 1. Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP, Meerpohl JJ. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta‐analyses. BMJ. 2013;346:f1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, et al. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):624‐634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . Guideline: sodium intake for adults and children. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/sodium_intake_printversion.pdf. Accessed July 2018. [PubMed]

- 4. GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators . Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1923‐1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lucko AM, Doktorchik C, Woodward M, et al. Percentage of ingested sodium excreted in 24‐hour urine collections: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2018;20(9):1220‐1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McLean RM, Farmer VL, Nettleton A, Cameron CM, Cook NR, Campbell N. Assessment of dietary sodium intake using a food frequency questionnaire and 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion: a systematic literature review. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(12):1214‐1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Petersen KS, Wu J, Webster J, et al. Estimating mean change in population salt intake using spot urine samples. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(5):1542‐1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . A comprehensive global monitoring framework including indicators and a set of voluntary global targets for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Revised WHO discussion paper (Version dated 25th July 2012). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/nmh/events/2012/discussion_paper2_20120322.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trieu K, Neal B, Hawkes C, et al. Salt reduction initiatives around the world ‐ a systematic review of progress towards the global target. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0130247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Canadian Institute for Health Research and Heart and Stroke foundation . Science of Salt Weekly e‐newsletter. Hypertension Talk Website [cited 2018 August 20]. http://www.whoccsaltreduction.org/portfolio/science-of-salt-weekly. Accessed August 18, 2018.

- 13. Arcand J, Webster J, Johnson C, et al. Announcing "up to date in the science of sodium". J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(2):85‐88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, Elliott P. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(3):791‐813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higgins J, Cochrane GS. Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed July 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pillay A, Trieu K, Santos JA, et al. Assessment of a salt reduction intervention on adult population salt intake in Fiji. Nutrients. 2017;9(12):E1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trieu K, Ieremia M, Santos J, et al. Effects of a nationwide strategy to reduce salt intake in Samoa. J Hypertens. 2018;36(1):188‐198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Petersen KS, Johnson C, Mohan S, et al. Estimating population salt intake in India using spot urine samples. J Hypertens. 2017;35(11):2207‐2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Donfrancesco C, Ippolito R, Lo Noce C, et al. Excess dietary sodium and inadequate potassium intake in Italy: results of the MINISAL study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23(9):850‐856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Polonia J, Martins L, Pinto F, Nazare J. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension and salt intake in Portugal: changes over a decade. The PHYSA study. J Hypertens. 2014;32(6):1211‐1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ogna A, Forni Ogna V, Bochud M, Paccaud F, Gabutti L, Burnier M. Prevalence of obesity and overweight and associated nutritional factors in a population‐based Swiss sample: an opportunity to analyze the impact of three different European cultural roots. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53(5):1281‐1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McLean R, Edmonds J, Williams S, Mann J, Skeaff S. Balancing sodium and potassium: estimates of intake in a New Zealand adult population sample. Nutrients. 2015;7(11):8930‐8938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mizéhoun‐Adissoda C, Houinato D, Houehanou C, et al. Dietary sodium and potassium intakes: data from urban and rural areas. Nutrition. 2017;33:35‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson C, Mohan S, Rogers K, et al. Dietary salt intake in urban and rural areas in India. A population survey of 1395 persons. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(1):e004547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Santos JA, Webster J, Land M‐A, et al. Dietary salt intake in the Australian population. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(11):1887‐1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cogswell ME, Loria CM, Terry AL, et al. Estimated 24‐hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion in US adults. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1209‐1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harris RM, Rose A, Hambleton IR, et al. Sodium and potassium excretion in an adult Caribbean population of African descent with a high burden of cardiovascular disease. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He FJ, Pombo‐Rodrigues S, Macgregor GA. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mente A, Dagenais G, Wielgosz A, et al. Assessment of dietary sodium and potassium in Canadians using 24‐hour urinary collection. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(3):319‐326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mapping salt reduction initiatives in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. McLaren L, Sumar N, Barberio AM, et al. Population‐level interventions in government jurisdictions for dietary sodium reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:Cd010166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Canada H. Guidance for the Food Industry on Reducing Sodium in Processed Foods. Ottawa, New Zealand: Bureau of Nutritional Sciences Food Directorate Health Products and Food Branch; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Webster J, Trieu K, Dunford E, Hawkes C. Target salt 2025: a global overview of national programs to encourage the food industry to reduce salt in foods. Nutrients. 2014;6(8):3274‐3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(1):3‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thow AM, Heywood P, Schultz J, Quested C, Jan S, Colagiuri S. Trade and the nutrition transition: strengthening policy for health in the Pacific. Ecol Food Nutr. 2011;50(1):18‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boutayeb A. The double burden of communicable and non‐communicable diseases in developing countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(3):191‐199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. John KA, Cogswell ME, Campbell NR, et al. Accuracy and usefulness of select methods for assessing complete collection of 24‐hour urine: a systematic review. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(5):456‐467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cogswell ME, Maalouf J, Elliott P, Loria CM, Patel S, Bowman BA. Use of urine biomarkers to assess sodium intake: challenges and opportunities. Annu Rev Nutr. 2015;35:349‐387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group . Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24 hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion. BMJ. 1988;297(6644):319‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stamler J, Elliott P, Dennis B, et al. INTERMAP: background, aims, design, methods, and descriptive statistics (nondietary). J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17(9):591‐608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McLean RM. Measuring population sodium intake: a review of methods. Nutrients. 2014;6(11):4651‐4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Swanepoel B, Schutte AE, Cockeran M, Steyn K, Wentzel‐Viljoen E. Monitoring the South African population’s salt intake: spot urine v. 24 h urine. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(3):480‐488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cappuccio FP, Beer M, Strazzullo P. Population dietary salt reduction and the risk of cardiovascular disease. A scientific statement from the European Salt Action Network. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;29(2):107‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. The INTERSALT Co‐operative Research Group . Appendix tables. Centre‐specific results by age and sex. J Hum Hypertens. 1989;3(5):331‐407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pavan L, Casiglia E, Pauletto P, et al. Blood pressure, serum cholesterol and nutritional state in Tanzania and in the Amazon: comparison with an Italian population. J Hypertens. 1997;15(10):1083‐1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turrini A. (CM) INN‐CA 1994–96.

- 47. Venezia A, Barba G, Russo O, et al. Dietary sodium intake in a sample of adult male population in southern Italy: results of the Olivetti Heart Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(5):518‐524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Polonia J, Maldonado J, Ramos R, et al. Estimation of salt intake by urinary sodium excretion in a Portuguese adult population and its relationship to arterial stiffness. Rev Port Cardiol. 2006;25(9):801‐817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elmadfa, Ibrahim, Verena, Nowak. (CM) EPITeen Project.

- 50. Chappuis A, Bochud M, Glatz N, Vuistiner P, Paccaud F, Burnier M. Swiss survey on salt intake: main results. Lausanne, Switzerland: Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Finch S, Lowe C, Bates CJ, Prentice A, Smithers G. Diet and Nutrition Survey: people aged 65 years and over; volume 1: Report of the diet and nutrition survey. London, UK: The Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fogarty AW, Lewis SA, McKeever TM, Britton JR. 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion in a population‐based study of 2,633 individuals in Nottingham. Am J Clin Nutrition. 2009;89;1901‐1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gregory J, Foster K, Tyler H, Wiseman M. The dietary and Nutritional Survey of British Adults. London, UK: HMSO Publications Centre; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Henderson L, Gregory J, Swan G. The national diet & nutrition survey: adults aged 19 to 64 years. Types and quantities of foods consumed. TSO; 2002.

- 55. Khaw K‐T, Bingham S, Welch A, et al. Blood pressure and urinary sodium in men and women: the Norfolk Cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC‐Norfolk). Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(5):1397‐1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. National Centre for Social Research UK . A Survey of 24 hour and Spot Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion in a Representative Sample of the Scottish Population. London, UK: National Center for Social Research; 2007. 30 p. [Google Scholar]

- 57. National Centre for Social Research UK . An Assessment of dietary Sodium Levels among Adults (aged 19–64) in the UK General Population in 2008, Based on Analysis of Dietary Sodium in 24 Hour Urine Samples. London, UK: National Centre for Social Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nelson M, Erens B, Bates B, Church S, Boshier T. Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey, vol. 3. London, UK: TSO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stamler J, Elliott P, Appel L, et al. Higher blood pressure in middle‐aged American adults with less education‐role of multiple dietary factors: the INTERMAP study. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17(9):655‐775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Williams DR, Bingham SA. Sodium and potassium intakes in a representative population sample: estimation from 24 h urine collections known to be complete in a Cambridgeshire village. Brit J Nutr. 1986;55(1):13‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garriguet D. (CM) Canadian Community Health Survey.

- 62. Garriguet D. Sodium consumption at all ages. Health Rep. 2007;18(2):47‐52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Scottish Centre for Social Research . A Survey of 24 Hour Urinary Sodium Excretion in a Representative Sample of the Scottish Population as a Measure of Salt Intake. Edinburgh, UK: Scottish Centre for Social Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shi Y, de Groh M, Morrison H, Robinson C, Vardy L. Dietary sodium intake among Canadian adults with and without hypertension. Chronic Dis Canada. 2011;31(2):79‐87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Simpson FO, Paulin JM, Phelan EL, et al. Further surveys in Milton, 1978 and 1981: blood pressure, height, weight and 24‐hour excretion of sodium and potassium. N Zeal Med J. 1982;95(722):873‐876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Thomson C, Colls AJDUoO. Twenty‐four Hour Urinary Sodium Excretion in Seven Hundred Residents of Otago and Waikato. Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Templeton R. National Nutrition Survey; 1997.

- 68. Melse‐Boonstra A, Rozendaal M, Rexwinkel H, et al. Determination of discretionary salt intake in rural Guatemala and Benin to determine the iodine fortification of salt required to control iodine deficiency disorders: studies using lithium‐labeled salt. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68(3):636‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ginnela, Brahmam, Nagalla B. (CM) Diet & Nutrition Assessment Surveys Among Rural Communities in Select States of India, by National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau; 2000.

- 70.Ginnela, Brahmam, Nagalla B. (CM) Diet & Nutrition Assessment Surveys Among Rural Communities in Select States of India. National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau; 2005.

- 71. Ginnela B, Nagalla B. Diet & Nutrition Assessment Surveys Among Rural Communities in Select States of India. Hyderabad, India: National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Radhika G, Sathya RM, Sudha V, Ganesan A, Mohan V. Dietary salt intake and hypertension in an urban south Indian population–[CURES ‐ 53]. J Assoc Phys India. 2007;55:405‐411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Beard TC, Eickhoff R, Mejglo ZA, Jones M, Bennett SA, Dwyer T. Population‐based survey of human sodium and potassium excretion. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1992;19(5):327‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Beard TC, Woodward DR, Ball PJ, Hornsby H, von Witt RJ, Dwyer T. The Hobart Salt Study 1995: few meet national sodium intake target. Med J Aust. 1997;166(8):404‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Charlton K, Yeatman H, Houweling F, Guenon S. Urinary sodium excretion, dietary sources of sodium intake and knowledge and practices around salt use in a group of healthy Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34(4):356‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Land MA, Webster J. Salt Intake in New South Wales, Australia ‐ Results of a 24‐hour Urinary Sodium Excretion Study in a Representative Adult Population Sample. Sydney, Australia: George Institute for Global Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Margerison C, Nowson C. Dietary intake and 24‐hour excretion of sodium and potassium. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr. 2006;15(Suppl. 3):S37. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Notowidjojo L, Truswell AS. Urinary sodium and potassium in a sample of healthy adults in Sydney, Australia. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr. 1993;2(1):25‐33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Holbrook JT, Patterson KY, Bodner JE, et al. Sodium and potassium intake and balance in adults consuming self‐selected diets. Am J Clin Nutri. 1984;40(4):786‐793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cooper R, Rotimi C, Ataman S, et al. The prevalence of hypertension in seven populations of west African origin. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(2):160‐168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Espeland MA, Kumanyika S, Wilson AC, et al. Statistical issues in analyzing 24‐hour dietary recall and 24‐hour urine collection data for sodium and potassium intakes. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(10):996‐1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Taylor EN, Curhan GC. Differences in 24‐hour urine composition between black and white women. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(2):654‐659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (USA) (2010) NHANES 2003‐2006.

- 84.Leske MC, Hennis A, Nemesure B. (CM) Identifying new genetic and obesity‐related factors contributing to prostate cancer risk in persons of African descent.

- 85.McGarvey, Stephen, Ana B. (CM) Western Samoa, 1990 (24 hr recall diet estimates).