Abstract

This study investigated the association between winter morning surge in systolic blood pressure (SBP) as measured by ambulatory BP monitoring and the housing conditions of subjects in an area damaged by the Great East Japan Earthquake. In 2013, 2 years after disaster, hypertensives who lived in homes that they had purchased before the disaster (n = 299, 74.6 ± 8.1 years) showed significant winter morning surge in SBP (+5.0 ± 20.8 mmHg, P < 0.001), while those who lived in temporary housing (n = 113, 76.2 ± 7.6 years) did not. When we divided the winter morning surge in SBP into quintiles, the factors of age ≥75 years and occupant‐owned housing were significant determinants for the highest quintile (≥20 mmHg) after adjustment for covariates. The hypertensives aged ≥75 years who lived in their own homes showed a significant risk for the highest quintile (odds ratio 5.21, 95% confidence interval 1.49‐18.22, P = 0.010). It is thus crucial to prepare suitable housing conditions for elderly hypertensives following a disaster.

Keywords: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, elderly hypertensives, occupant‐owned housing, temporary housing, the Great East Japan Earthquake, winter morning surge in blood pressure

1. INTRODUCTION

The Great East Japan Earthquake occurred in the Tohoku district of Japan on March 11, 2011. The great earthquake triggered a powerful tsunami, which provoked catastrophic damage, especially in coastal regions. Almost all buildings were completely destroyed, and thousands of residents in the affected areas were forced to move from their own homes or apartments to temporary housing. Even today, more than 7 years after the disaster, many of the displaced victims continued to live in temporary housing. The quality of life in such housing may affect the health of evacuees, since temporary housing tends to be simpler, less spacious, and less comfortable than occupant‐owned housing.

Blood pressure (BP), including 24‐hour ambulatory BP, fluctuates with the seasons and is generally higher in winter and lower in summer.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Previous studies have also demonstrated that seasonal BP variations are more highly associated with indoor temperature than outdoor temperature8, 9 and that indoor temperature is mainly determined by the temperature or permanent nature of residential housing.4, 10 Therefore, housing conditions may be one of the greatest determinants of the seasonal BP variations. However, there have been no studies investigating the association between seasonal BP variations and the nature of the residential housing in areas damaged by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Elderly individuals show more highly exaggerated BP variability than younger people, mainly due to the autonomic nervous dysfunction in the former.11, 12, 13, 14 The elderly also show higher BP levels in the winter than in the summer, while younger individuals do not exhibit this seasonal BP difference.15, 16, 17 Therefore, compared to the BP levels of young people, those of the elderly would be more likely to be changed due to differences in housing conditions; however, information is limited regarding the association between seasonal BP variations and housing conditions in the elderly.

To investigate this association, we used data from the Minamisanriku study, a prospective observational study of outpatients of the Minamisanriku hospital who experienced changes in their housing status, to test our hypothesis that seasonal BP variations would be associated with housing conditions (especially temporary housing status), and this association would be stronger in the elderly than in younger people.

2. METHODS

2.1. The Minamisanriku study

Minamisanriku is a town located in the northeast region of Miyagi Prefecture in the Tohoku district of Japan (Figure S1A). On 11 March, the 9.0‐magnitude Great East Japan Earthquake caused a massive tsunami (more than 16 m) that hit Minamisanriku (Figure S1B). Approximately 800 people died or disappeared, and approximately 60% of the town's residential area was demolished by the tsunami (Figure S1C). A total of 6000 people (40% of the total population of Minamisanriku) had to move to temporary housing in March 2011 (Figure S2A) because their homes were destroyed. Even now, 7 years after the disaster, approximately 1800 people are still forced to live in temporary housing, while others have purchased new homes (25%), rented houses or apartments (30%), or moved to areas other than Minamisanriku (45%).

Immediately after the great earthquake, we developed an information and communication technology (ICT)‐based home BP monitoring system (the Disaster Cardiovascular Prevention [DCAP] network) in Minamisanriku to reduce cardiovascular disease risk by controlling the home BP levels of hypertensive survivors over the long‐term.18 The DCAP network is still in use, and strict home BP control has been achieved in most of the 321 eligible patients.19

Having confirmed that the home BP levels were under control, we have continued to regularly perform 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) twice‐yearly (summer and winter) since the winter of 2012 in the same study population in order to achieve perfect control of not only home BP levels but also 24‐hour ambulatory BP levels.20

The protocol of this study was approved by the ethics committee of the Jichi Medical University School of Medicine. We received informed consent from all patients for this research.

2.2. Blood pressure and other measurements

Clinic BP was measured at each visit using a validated cuff oscillometric device according to the Japanese Society of Hypertension 2009 guidelines.21 BP was measured after patients had rested for a few minutes in a seated position. Two consecutive BP measurements were taken at a 1‐ and 2‐minutes interval, and the average of the measurements was used as the clinic BP value.

Noninvasive 24‐hour ABPM was performed with a validated automatic device (TM‐2433; A&D Co., Tokyo) that recorded the patients BP using an oscillometric method at 30‐minute intervals throughout the 24‐hour day. Morning BP was defined as the average of BPs during the first 2 hours after waking. Nighttime BP was defined as the average BP values over the period from when patients went to bed until they woke in the morning. Daytime BP was defined as the average BP for the rest of the day.

In the present study, we used the clinic and ambulatory BP values in summer 2013 (July to September) and in winter (December 2013 to March 2014). We defined winter morning surge in systolic BP (SBP) as the morning SBP value in winter minus the morning SBP value in summer for both ABPM measurements. Only the patients who had undergone ABPM both in summer and in winter were eligible for this study.

The diagnostic criteria of cardiovascular risk factors were as follows. Dyslipidemia was defined as a total cholesterol level of over 240 mg/dL or current use of a lipid‐lowering drug, and diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting glucose level of ≥126 mg/dL and/or a casual glucose level of ≥200 mg/dL or current use of an antidiabetic drug. Coronary heart disease (CHD) was defined as angina pectoris or myocardial infarction. Stroke events consisted of cerebral infarction and cerebral hemorrhage; transient ischemic brain attacks were not included. Daily drinking was defined as the consumption of 20‐30 mL (men) or 10‐20 mL (women) ethanol three times a week or more.

Meteorological parameters of outdoor temperature were obtained from the Japan Meteorological Station (http://www.jma.go.jp). The results for the Shizugawa area, which is the closest measurement point to Minamisanriku hospital in the town of Minamisanriku, were used.

2.3. Lifestyle modification and antihypertensive medication

Throughout the study period, the recommendation of lifestyle modification and prescriptions of antihypertensive medication were performed by a physician (MN). Details of the antihypertensive medications were checked at the time of ABPM in both summer and winter. The antihypertensive medications were classified into seven types: calcium channel blockers (CCB), angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), diuretics, β‐blockers, α‐blockers, and aldosterone receptor antagonist (eplerenone). Increases in antihypertensive medications were defined as increases in the number of antihypertensive medications, either by the addition of an antihypertensive from a different class or by an increase in the dosage of a current antihypertensive medication. Decreases in antihypertensive medications were defined as decreases in the number or dosage of antihypertensive medications.

2.4. Characteristics of own housing and temporary housing

“Occupant‐owned housing” was defined as a house owned by a subject of this study, or by one or more of their family members. Traditionally, occupant‐owned homes are constructed mainly of wood and have large rooms, and thus tended to be poorly insulated (Figure S2B). In winter, this would lead to lower temperature in the morning than the afternoon. On the other hand, “temporary housing” was defined as residences erected to house people who had lost their homes as a result of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Temporary housing is generally prefabricated, and the rooms tend to be less spacious, so the level of insulation tends to be greater (Figure S2A).

The local government defined those eligible for temporary housing as “any person who has lost a place of residence due to the disaster and is having difficulty securing a new dwelling for long‐term occupation through his/her own effects (eg, household economy)” without any distinction regarding the type of temporary housing.22 None of the subjects of this study moved from one house to another during the study period.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (interquartile range), or percentage. The mean BP parameters in summer and in winter were compared using paired t test. Other clinical parameters of continuous variables were compared using two‐sided unpaired t test, and proportions were compared using chi‐squared statistics. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. Adjusted covariates included age ≥75 years, sex (male), body mass index (BMI) ≥25.0 kg/m2, current smoking, daily drinking, history of CHD, history of stroke, dyslipidemia, or diabetes mellitus, increase in antihypertensive medications, and decrease in antihypertensive medications. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 24.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Change in clinic and ambulatory blood pressure parameters

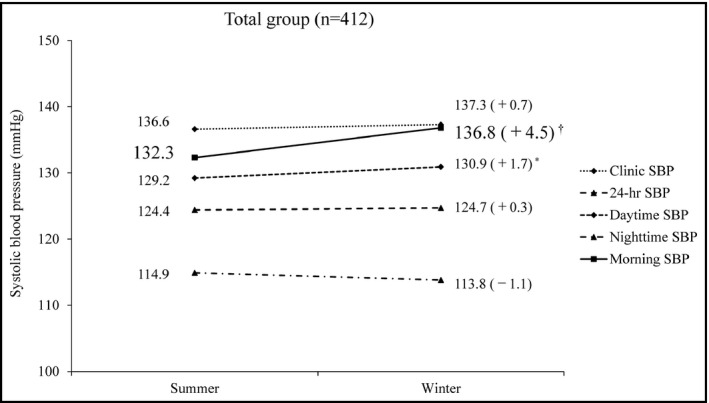

We compared clinic and ambulatory (including 24‐hour, daytime, nighttime, and morning) BP parameters between summer and winter in the complete subject group (Figure 1). Although each BP parameter was well‐controlled, morning SBP and daytime SBP in winter were significantly higher than those in summer: morning SBP, 132.3 ± 17.3 vs 136.8 ± 17.2 mmHg, +4.5 ± 20.1 mmHg (P < 0.001); daytime SBP, 129.2 ± 11.9 vs 130.9 ± 10.9 mmHg, +1.7 ± 11.8 mmHg (P = 0.003). Twenty‐four‐hour SBP, nighttime SBP, and clinic SBP were not significantly different between winter and summer.

Figure 1.

Changes in clinic and ambulatory systolic blood pressure levels in the total group. Means were compared using a paired t test between summer and winter. *P < 0.01, † P < 0.001 vs summer

3.2. Patient characteristics

We divided the study patients according to their housing conditions, that is, we divided them into a temporary and an occupant‐owned housing group. Table 1 provides the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients between the occupant‐owned housing group (n = 299) and the temporary housing group (n = 113). There were no significant differences between the two groups. The patients living in temporary housing tended to be older and to have a higher percentage of subjects aged ≥75 years, but these differences were not significant. The median age of subjects who owned their own housing was 32.0 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study patients between occupant‐owned housing (n = 229) and temporary housing (n = 113)

| Occupant‐owned housing (n = 299) | Temporary housing (n = 113) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 74.6 ± 8.1 | 76.2 ± 7.6 | 0.069 |

| Age ≥75 y, % | 55.5 | 64.6 | 0.096 |

| Male, % | 30.8 | 37.2 | 0.216 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.1 ± 3.9 | 25.3 ± 3.4 | 0.701 |

| Current smoking, % | 6.8 | 9.7 | 0.309 |

| Daily drinking, % | 18.2 | 23.2 | 0.253 |

| Preexisting CHD, % | 2.7 | 5.3 | 0.188 |

| Preexisting stroke, % | 5.0 | 7.1 | 0.416 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 62.2 | 70.8 | 0.104 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 19.1 | 23.0 | 0.373 |

| Housing age, y | 32.0 (20.0‐50.0) | ‐ | ‐ |

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or percentage. Preexisting CHD includes preexisting angina pectoris and myocardial infarction. Means were compared using unpaired t test, and proportions were compared using Pearson's chi‐square statistics.

CHD, coronary heart disease; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2 provides a comparison of the antihypertensive medication changes between the occupant‐owned housing and temporary housing groups. In both groups, the physician prescribed a greater number of antihypertensive medications in winter than in summer, but there were no significant differences between the two groups (P = 0.860). In the comparison within the antihypertensive medication classes, the patients who owned their own homes exhibited an increase in ARB prescriptions in winter. Within the other medication classes, there were no significant differences between patients in temporary housing and those in occupant‐owned housing. In the comparison of the antihypertensive medication changes between subjects in the two housing groups, diuretic use was found to be significantly increased in winter in the patients living in temporary housing compared to those living in occupant‐owned housing (P = 0.004). With respect to the changes in antihypertensive medication use, there were no significant differences between occupant‐owned housing and temporary housing.

Table 2.

Comparison of antihypertensive medication changes between occupant‐owned housing (n = 229) and temporary housing (n = 113)

| Occupant‐owned housing (n = 299) | Temporary housing (n = 113) | aComparison the changes own housing vs temporary housing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Winter | Change (Winter‐Summer) | Summer | Winter | Change (Winter‐Summer) | ||

| P value | |||||||

| Number of antihypertensive drugs, n | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | +0.12 ± 0.41‡ | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | +0.13 ± 0.38† | 0.860 |

| Antihypertensive medications | |||||||

| CCB, n (%) | 227 (75.9) | 239 (79.9) | +12 (4.0) | 83 (74.1) | 88 (78.6) | +5 (4.5) | 0.851 |

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 15 (5.0) | 7 (2.3) | −8 (−2.7) | 3 (2.7) | 1 (0.9) | −2 (−1.8) | 0.594 |

| ARB, n (%) | 209 (69.9) | 240 (80.3) | +31 (10.4)* | 85 (75.9) | 93 (83.0) | +8 (7.1) | 0.309 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 118 (39.5) | 118 (39.5) | 0 (0) | 52 (46.4) | 55 (49.1) | +3 (2.7) | 0.004 |

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 9 (3.0) | 9 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 7 (6.3) | 7 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Alpha blocker, n (%) | 20 (6.7) | 20 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.5) | 5 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Eplerenone, n (%) | 4 (1.3) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.6) | 4 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Changes of antihypertensive medications | |||||||

| Increased group, n (%) | 157 (52.5) | 57 (50.4) | |||||

| Increase in the number, n (%) | 44 (14.7) | 13 (11.5) | 0.400 | ||||

| Increase in the dosage, n (%) | 113 (37.8) | 44 (38.9) | 0.831 | ||||

| Decreased group, n (%) | 12 (4.0) | 2 (1.8) | |||||

| Decrease in the number, n (%) | 7 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | 0.339 | ||||

| Decrease in the dosage, n (%) | 5 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 0.552 | ||||

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD or number (percentage). Means were compared using paired t test, and proportions were compared using Pearson's chi‐square statistics between summer and winter. The changes of antihypertensive drugs indicated an increase or decrease between summer and winter.

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CHD, coronary heart disease; SD, standard deviation.

aComparison of the changes between occupant‐owned housing and temporary housing using unpaired t test or Pearson's chi‐square statistics.

*P < 0.05, † P < 0.01, ‡ P < 0.001 for difference vs summer.

3.3. Winter morning surge in systolic blood pressure

The mean outdoor temperatures when we conducted ABPM were as follows: 20.8°C in July 2013, 23.9°C in August 2013, 20.6°C in September 2013, 3.4°C in December 2013, 0.3°C in January 2014, 0.4°C in February 2014, and 4.3°C in March 2014.

We compared the winter morning surge in SBP under each housing condition (Table 3). The patients living in their own houses showed a significant winter morning surge in SBP (+5.0 ± 20.8 mmHg, P < 0.001). On the other hand, those living in temporary housing did not. In the analysis of winter morning surge in SBP by the changes in antihypertensive medications, the patients with no change in medications showed significant winter morning surge in SBP in both occupant‐owned housing and temporary housing, and temporary housing and the patients with decrease of medications tended to show a high winter morning surge in SBP (Table S1).

Table 3.

Comparison of winter morning surge in systolic blood pressure

| Total group (n = 412) | Occupant‐owned housing (n = 299) | Temporary housing (n = 113) | Comparison the changes own housing vs temporary housing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer (mmHg) | Winter (mmHg) | Change (mmHg) (Winter‐Summer) | P value | Summer (mmHg) | Winter (mmHg) | Change (mmHg) (Winter‐Summer) | P value | Summer (mmHg) | Winter (mmHg) | Change (mmHg) (Winter‐Summer) | P value | |

| P value | ||||||||||||

| 132.3 ± 17.3 | 136.8 ± 17.2 | +4.5 ± 20.1 | <0.001 | 132.7 ± 17.5 | 137.7 ± 17.5 | +5.0 ± 20.8 | <0.001 | 131.2 ± 16.7 | 134.5 ± 16.2 | +3.3 ± 18.0 | 0.056 | 0.437 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Means were compared using paired t test between summer and winter in the total, occupant‐owned housing, and temporary housing groups, respectively. Comparison of the changes between occupant‐owned housing and temporary housing using unpaired t test.

SD, standard deviation.

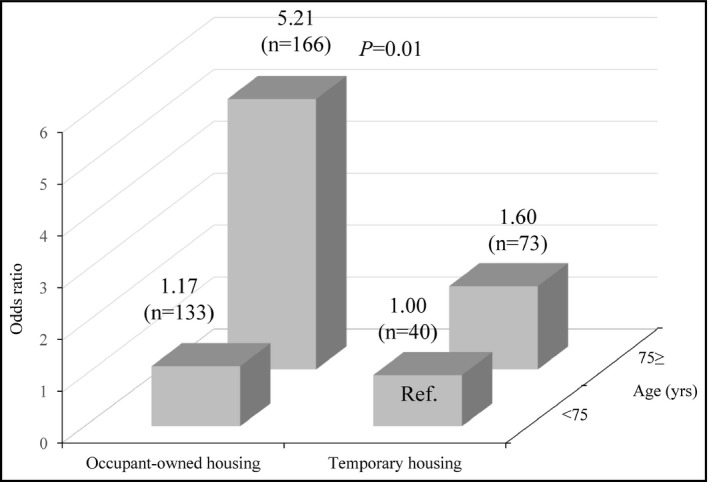

We next divided the winter morning surge in SBP into quintile and calculated the OR for the highest quintile (≥20 mmHg) (Figure S3). In the univariate analysis, the factors of age ≥75 years and occupant‐owned housing were significant determinants of increased risk for the highest quintile, while the factor of BMI ≥25 kg/m2 was a significant determinant of decreased risk for the highest quintile. Even after controlling the covariates, the factors of age ≥75 years and occupant‐owned housing were significant determinants of increased risk for the highest quintile: For age ≥75 years, the OR was 3.73 (95% CI 2.00‐6.95, P < 0.001), and for occupant‐owned housing, the OR was 2.58 (95% CI 1.29‐5.16, P = 0.007) (Table 4). We set the patients of age <75 years who were living in temporary housing as the reference group and calculated the relative risk for the highest quintile. The patients who owned their own homes and who were ≥75 years of age showed a significantly high risk for the highest quintile (OR 5.21, 95% CI 1.49‐18.22, P = 0.010) (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for the highest quintile (Q5) of winter morning surge in systolic blood pressure

| Univariate regression analysis | Multivariate regression analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age ≥75 y | 3.36 | 1.89‐5.97 | <0.001 | 3.73 | 2.00‐6.95 | <0.001 |

| Male | 0.91 | 0.54‐1.54 | 0.722 | 0.89 | 0.37‐2.12 | 0.793 |

| Body mass index ≥25 kg/m2 | 0.55 | 0.33‐0.91 | 0.021 | 0.65 | 0.38‐1.12 | 0.118 |

| Current smoking | 0.77 | 0.29‐2.08 | 0.608 | 0.80 | 0.25‐2.64 | 0.719 |

| Daily drinker | 0.84 | 0.44‐1.59 | 0.588 | 1.12 | 0.43‐2.93 | 0.823 |

| Preexisting CHD | 0.31 | 0.04‐2.37 | 0.257 | 0.21 | 0.03‐1.68 | 0.141 |

| Preexisting stroke | 2.31 | 0.94‐5.65 | 0.067 | 2.14 | 0.76‐6.00 | 0.148 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.05 | 0.63‐1.75 | 0.855 | 1.12 | 0.61‐2.06 | 0.717 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.07 | 0.59‐1.94 | 0.833 | 0.83 | 0.42‐1.66 | 0.597 |

| Increase in antihypertensives | 0.84 | 0.52‐1.36 | 0.476 | 0.82 | 0.48‐1.41 | 0.470 |

| Decrease in antihypertensives | 2.86 | 0.99‐8.29 | 0.053 | 3.02 | 0.90‐10.12 | 0.073 |

| Occupant‐owned housing | 2.26 | 1.20‐4.29 | 0.012 | 2.58 | 1.29‐5.16 | 0.007 |

Preexisting CHD includes preexisting angina pectoris and myocardial infarction. Multivariate regression analysis was adjusted for age ≥75 y, sex (male), body mass index ≥25.0 kg/m2, current smoking, daily drinking, history of CHD, history of stroke, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, increase in antihypertensives, decrease in antihypertensives, and occupant‐owned housing.

CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Relative risk for the highest quintile of winter morning surge in systolic blood pressure. Logistic regression analysis was used with adjustment for sex, body mass index ≥25 kg/m2, current smoking, daily drinking, preexisting coronary heart disease, preexisting stroke, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, increase in antihypertensives, and decrease in antihypertensives. Temporary housing and age <75 y were used as a reference

Even when the analysis was limited to the patients ≥75 years of age, home ownership was the significant determinant of the highest quintile of winter morning surge in SBP (Table S2). In addition, when the analyses including the information of antihypertensive medication use in winter were conducted in order to account for potentially confounding factors, the results were similar (Table S3, Figure S4).

4. DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study were as follows. First, morning SBP exhibited a greater change compared with other SBP parameters from the summer to winter seasons. Second, the factors of age ≥75 years and home ownership were significant determinants of increased risk for the highest quintile of winter morning surge in SBP. Third, the patients who were ≥75 years of age and owned their own homes showed a higher risk for the highest quintile of winter morning surge in SBP compared to other patients. This is the first study to demonstrate a significant association between seasonal BP changes and the housing conditions in an area damaged by the Great East Japan Earthquake. It is likely that winter morning surge in BP would be associated with increased cardiovascular events during winter.23, 24 We should pay attention to the onset of cardiovascular events triggered by winter morning surge in BP, especially in elderly hypertensive patients who own their homes.

In the present study, occupant‐owned housing was a significant risk factor for the highest quintile of winter morning surge in SBP. In other words, this finding indicates that temporary housing would be less likely to cause a winter morning surge in SBP. This result ran counter to our expectations. In the past, most of the temporary housing for use after natural disasters in Japan consisted of container houses made from tinplate. These temporary homes had water and electricity, but they were small, had no soundproofing, were poorly insulated with poor airtightness, and were not sufficiently cold‐resistant.25 However, since more recent temporary homes have come equipped with properly insulated walls and double‐glazed windows, they are much more airtight and less subject to intraday temperature differences. Over the long‐term following a disaster, our results indicated that appropriate temporary housing could be better for avoiding excessive winter SBP surge compared with older occupant‐owned housing. It has been reported that BP elevation after an earthquake was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.26, 27 Thus, early interventions in the provision of appropriate living conditions for evacuees are needed in order to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease associated with earthquake.

The participants of this study showed a seasonal BP variation – namely, morning SBP was significantly higher in winter than in summer. A previous study conducted in Iwate Prefecture in the same Tohoku district of Japan demonstrated that morning SBP measured by ABPM was significantly higher in winter than in summer (+7.5 mmHg).28 Another study conducted in Japan also demonstrated that the maximum‐minimum difference of home morning SBP in a year was +6.7 mmHg (the maximum BP was observed in January and the minimum BP in July).7 Our results confirmed these earlier results that morning SBP was higher in winter than in summer. Compared to the winter BP surge in these studies, our study population showed lower winter morning surge in SBP. Since the BP levels of the study participants were well‐controlled, we conclude that we successfully suppressed the exaggerated winter BP surge.

In the morning, the sympathetic nervous system and renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system are activated. Cold temperature also increases sympathetic tone, which increases BP levels and myocardial oxygen demand.29 In addition to cold outdoor/indoor temperature, any seasonal variation in salt intake, adiposity, or physical activity could also potentially lead to changes in BP. Various factors would induce a morning BP elevation in winter. Since morning BP is associated with cardiovascular risk,30, 31, 32 it is essential to control morning BP strictly, especially in winter.

In our study, 90.5% of the study patients were over 65 years. Compared to young patients, elderly patients show large seasonal BP variations.3, 7, 15 This is why elderly patients often have impaired autonomic nervous systems, which results in BP fluctuation.11, 12, 13, 14 In addition, external factors such as old age of homes and absence of air conditioning, which are often seen in occupant‐owned homes of the elderly, might also affect winter BP surge.

In the present study, the threshold of the highest quintile of the winter morning surge in SBP was 20 mmHg. This result suggested that some patients had marked SBP fluctuations by seasonal temperature variations and that this contributed to the risk of cardiovascular events. A recent meta‐analysis revealed that each 10 mmHg reduction in SBP significantly reduced the risk of major CVD events (relative risk [RR] 0.80), coronary heart disease (0.83), stroke (0.73), and heart failure (0.72), leading to a significant reduction in all‐cause mortality (0.87).33 Thus, it is very important to suppress any marked SBP fluctuation throughout the year in order to prevent the onset of CVD events.

4.1. Study strength and limitations

The strengths of this study were as follows: (1) This was the first database with a long follow‐up that included regular ABPM measurements (twice‐yearly, in summer and in winter) in an area damaged by the great earthquake; (2) we checked the patients’ drug information in detail at the time of the ABPM.

Our study also had some limitations. First, we did not collect data on the indoor and outdoor temperatures at the time of the ABPM. In addition, a proper home heating system might be more important for suppressing the exaggerated winter BP surge than proper housing conditions. Second, various types of occupant‐owned housing were included, that is, very old to recently built homes. Further studies will be needed to address how these differences in housing, that is, old or new housing, could affect the winter morning surge in SBP. Third, we could not assess the influence of the great earthquake on the results of this study. Fourth, although ABPM measurement was conducted in the seasons of summer and winter, the actual months of the measurement varied. Finally, this study was performed only in selected areas. Thus, the findings of this study may not be generalized to any other region.

5. CONCLUSION

Morning SBP measured by ABPM showed a larger winter surge than 24‐hour, daytime, or nighttime SBP measured by ABPM. The housing condition, that is, occupant‐owned or temporary housing, was a determinant of the winter morning surge in SBP, especially in the elderly of ≥75 years. This is the first study to demonstrate a significant association between seasonal BP changes and the housing conditions in a damaged area after the Great East Japan Earthquake. We should pay close attention to the onset of cardiovascular events triggered by winter morning surge in SBP, especially in elderly hypertensive patients who live in their own homes. Our results underscore the importance of preparing suitable housing conditions in damaged areas after a natural disaster.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

Nishizawa M, Fujiwara T, Hoshide S, et al. Winter morning surge in blood pressure after the Great East Japan Earthquake. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:208‐216. 10.1111/jch.13463

REFERENCES

- 1. Giaconi S, Ghione S, Palombo C, et al. Seasonal influences on blood pressure in high normal to mild hypertensive range. Hypertension. 1989;14:22‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sega R, Cesana G, Bombelli M, et al. Seasonal variations in home and ambulatory blood pressure in the PAMELA population. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1585‐1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenthal T. Seasonal variations in blood pressure. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2004;13:267‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewington S, Li L, Sherliker P, et al.; China Kadoorie Biobank study collaboration . Seasonal variation in blood pressure and its relationship with outdoor temperature in 10 diverse regions of China: the China Kadoorie Biobank. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1383‐1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Modesti PA, Morabito M, Massetti L, et al. Seasonal blood pressure changes: an independent relationship with temperature and daylight hours. Hypertension. 2013;61:908‐914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stergiou GS, Myrsilidi A, Kollias A, Destounis A, Roussias L, Kalogeropoulos P. Seasonal variation in meteorological parameters and office, ambulatory and home blood pressure: predicting factors and clinical implications. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:869‐875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanazawa T, Asayama K, Watabe D, et al. Seasonal variation in self‐measured home blood pressure among patients on antihypertensive medications: HOMED‐BP study. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:284‐290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saeki K, Obayashi K, Iwamoto J, et al. Influence of room heating on ambulatory blood pressure in winter: a randomised controlled study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:484‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saeki K, Obayashi K, Iwamoto J, et al. Stronger association of indoor temperature than outdoor temperature with blood pressure in colder months. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1582‐1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim YM, Kim S, Cheong HK, Ahn B, Choi K. Effects of heat wave on body temperature and blood pressure in the poor and elderly. Environ Health Toxicol. 2012;27:e2012013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kario K, Pickering TG. Blood pressure variability in elderly patients. Lancet. 2000;355:1645‐1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parati G, Ochoa JE, Lombardi V, Bilo G. Assessment and management of blood‐ressure variability. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:143‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kario K. Orthostatic hypertension‐a new haemodynamic cardiovascular risk factor. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:726‐738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kario K. Prognosis in relation to blood pressure variability: pro side of the argument. Hypertension. 2015;65:1163‐1169; discussion 1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brennan PJ, Greenberg G, Miall WE, Thompson SG. Seasonal variation in arterial blood pressure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;285:919‐923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stout RW, Crawford V. Seasonal variations in fibrinogen concentrations among elderly people. Lancet. 1991;338:9‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sheng CS, Cheng YB, Wei FF, et al. Diurnal blood pressure rhythmicity in relation to environmental and genetic cues in untreated referred patients. Hypertension. 2017;69:128‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kario K, Nishizawa M, Hoshide S, et al. Development of a disaster cardiovascular prevention network. Lancet. 2011;378:1125‐1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nishizawa M, Hoshide S, Okawara Y, Matsuo T, Kario K. Strict blood pressure control achieved using an ICT‐based home blood pressure monitoring system in a catastrophically damaged area after a disaster. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:26‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kario K. Evidence and perspectives on the 24‐hour management of hypertension: hemodynamic biomarker‐initiated ‘anticipation medicine’ for zero cardiovascular event. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;59:262‐281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, et al.; Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee . The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2009). Hypertens Res. 2009;32:3‐107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ito K, Tomata Y, Korure M, et al. Housing type after the Great East Japan Earthquake and loss of motor function in elderly victims: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kario K. Caution for winter morning surge in blood pressure: a possible link with cardiovascular risk in the elderly. Hypertension. 2006;47:139‐140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang L, Li L, Lewington S, et al.; China Kadoorie Biobank Study Collaboration . Outdoor temperature, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease mortality among 23 000 individuals with diagnosed cardiovascular diseases from China. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1178‐1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takahashi S, Yonekura Y, Sasaki R, et al. Weight gain in survivors living in temporary housing in the tsunami‐stricken area during the recovery phase following the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kario K. Disaster hypertension – its characteristics, mechanism, and management ‐. Circ J. 2012;76:553‐562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aoki T, Takahashi J, Fukumoto Y, et al. Effect of the Great East Japan Earthquake on cardiovascular diseases. Circ J. 2013;77:490‐493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fujiwara T, Kawamura M, Nakajima J, Adachi T, Hiramori K. Seasonal differences in diurnal blood pressure of hypertensive patients living in a stable environmental temperature. J Hypertens. 1995;13:1747‐1752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marchant B, Ranjadayalan K, Stevenson R, Wilkinson P, Timmis AD. Circadian and seasonal factors in the pathogenesis of acute myocardial infarction: the influence of environmental temperature. Br Heart J. 1993;69:385‐387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, et al. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation. 2003;107:1401‐1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, et al. Prediction of stroke by home “morning” versus “evening” blood pressure values: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2006;48:737‐743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoshide S, Yano Y, Haimoto H, et al.; J‐HOP Study Group . Morning and evening home blood pressure and risks of incident stroke and coronary artery disease in the Japanese general practice population: the Japan morning surge‐home blood pressure study. Hypertension. 2016;68:54‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957‐967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials