Abstract

There are concerns that specific risk factors may alter the benefits of thrombolysis in stroke patients with controlled contraindications including hypertension. The objective of this study was to evaluate the association between clinical risk factors and outcomes in ischemic stroke patients that received thrombolysis therapy pretreated with antihypertensive medications. Using data obtained from a stroke registry, a non‐randomized retrospective data analysis was conducted on patients with the primary diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke with hypertension pretreated with antihypertensive medications. The association between clinical risk factors and functional ambulatory outcome was determined using logistic regression while odd ratios (OR) were used to predict the odds of achieving improved ambulatory outcome in thrombolysis treatment status. Improved or poor functional ambulatory outcome was considered as the end point in our analysis. A total of 4665 acute ischemic stroke patients were identified, of whom 1446 (31.0%) were eligible for thrombolysis, while 3219 were not, and 595 received rtPA, of whom 288 were on antihypertensive medications, while 233 were not. In the rtPA group with antihypertensive (anti‐HTN) medication, only NIHSS score (OR = 1.094, 95% CI, 1.094‐1.000, P = 0.005) was associated with improved functional outcome while patients with congestive heart failure (OR = 0.385, 95% CI, 0.385‐0.159, P = 0.035) and patients with a history of previous TIA (OR = 0.302, 95% CI, 0.302‐0.113, P = 0.017) were more likely to be associated with poor functional outcomes. Congestive heart failure and TIA are independent predictors of functional outcomes in stroke patients pretreated with antihypertensive medications prior to thrombolysis therapy.

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, ambulation, antihypertensive medication, congestive heart failure, hypertension, thrombolysis

1. INTRODUCTION

Major classes of anti‐HTN agents including calcium channel blockers (CCBs), diuretics, inhibitors of angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE), and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are known to reduce the risk of stroke.1, 2 Although the treatment of hypertension is known to significantly reduce the risk of first and recurrent stroke,3 there is no convincing evidence favoring one class of antihypertensive drugs over another as monotherapy for secondary prevention in patients who have had a stroke. While some anti‐HTN agents have neuroprotective effects,4, 5 clinical data remain controversial regarding the pretreatment effects of anti‐HTN drugs on the treatment outcome in stroke patients. Some studies have reported beneficial effects of pretreatment with beta‐blockers,6 CCBs,7 ACE inhibitors,8 or ARBs.9 However, others did not find an association between pretreatment with anti‐HTN and post‐rtPA treatment outcome in acute ischemic stroke patients.10, 11

In general, untreated hypertension in acute ischemic stroke is linked with poor treatment outcomes.12 Consequently, current guidelines13 recommend the control of hypertension in the acute stage of stroke, but there are concerns that some baseline clinical risk factors may alter the benefits of thrombolysis resulting in poor outcomes, even in stroke patients with treated hypertension.14 This raises the question of (a) what are other clinical risk factors apart from hypertension that alter the benefits of thrombolysis and (b) can these other baseline risk factors identify patients in whom thrombolysis does not lead to a clinical benefit in stroke patients with controlled hypertension?

Several studies15, 16 that determined the association between initial stroke severity and outcome using the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at onset as a strong predictor of stroke outcome reveal favorable, unfavorable, and neutral effects of anti‐HTN on outcomes for stroke treatment. In other studies,11 a prior use of anti‐HTN medications did not help to reduce the severity of stroke or increase the rate of favorable outcome. The observed discrepancies of pretreatment with anti‐HTN agents on thrombolysis and outcomes may be attributed to several factors. One possibility is that other baseline clinical risk factors may alter the benefits of thrombolysis and outcomes in thrombolyzed stroke patients with anti‐HTN, when compared to thrombolyzed without anti‐HTN or vice versa. We tested this hypothesis in a population of rtPA group with anti‐HTN medications compared with rrtA group without anti‐HTN medication using functional ambulatory outcome for measurement.

Most thrombolyzed stroke patients often cite improved motor functions as their main recovery goal.18, 19 Stroke is a clinical disorder that cripples motor activities with a spectrum of impairments in ambulatory functions.20, 21 Therefore, an accurate knowledge of ambulatory activities before and after recovery is important to evaluate functional outcome following thrombolysis therapy in anti‐HTN‐treated stroke patients. In addition, ischemic stroke is a common etiology for physical immobility,22, 23 and the recovery of motor functions would provide a direct evaluation of daily life mobility before, after thrombolysis treatment, and during the recovery period. The current study analyzed the ambulatory activities to develop functional outcome measures that predicted baseline clinical characteristics associated functional outcome in thrombolyzed stroke patients with a pretreatment history of antihypertensive medication.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

This IRB approved retrospective study consisted of ischemic stroke patients who were admitted to the Greenville Health System Greenville, SC, USA between January 2010 and June 2016. Subjects that presented with ischemic stroke within 24 hours of symptom onset based on relevant ischemic lesions on CT or brain MRI were included in the analysis. Data on clinical characteristics and laboratory analysis were collected directly from the stroke registry. The registry has been described in previous studies.23, 24 Collected data included patients medical history factors of: hypertension, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, previous stroke, previous TIA, congestive heart failure (CHF), carotid artery stenosis, peripheral vascular disease, history of smoking, and diabetes. Percentages were reported for all variables. Patients ambulatory data were retrieved, and scores ranged from 0 to 3 as follows: undocumented (0), patients not able to ambulate (1), able to ambulate with assistance (2), and able to ambulate independently (3). The validity of the scoring has been described in a previous study.23 Data regarding the ambulatory status for each patient were tracked and collected on admission, during admission, and after discharge. This allowed us to analyze functional ambulation as a measure for functional outcome, with patients demonstrating an improvement or no improvement in ambulation at discharge compared to ambulation upon admission. Moreover, patient demographic variables associated with a history of using anti‐HTN medications were evaluated. These variables included age, race, gender, medical history, medication history, stroke severity (NIHSS) score, risk of mortality GWTG score, and body mass index (BMI).

2.2. Statistical analysis

Bivariate group comparisons of baseline characteristics between the rtPA and non rtPA groups, those with improved and not improved functional ambulatory outcomes, were determined using the Pearson χ 2 test, or Student’s t test according to the type of variable. Precisely, all continuous variables were analyzed using a Student t test, while discrete variables were analyzed using Pearson’s chi‐squared analyses. In the multivariable analysis, variables were retained if the resulting P‐value was <0.001, and all variables with P‐values >0.001 were excluded and eliminated stepwise. Variables that were initially eliminated were re‐added and kept in the model if they fulfilled the criteria of P < 0.001. Adjustments were made for clinically important covariates that were significantly different in the unadjusted univariate analysis (backward elimination approach with conventional P value <0.05). Our primary outcome measures were clinical risk factors that are significantly associated with functional outcome following thrombolysis therapy in anti‐HTN‐treated patients. This allowed us to determine whether the association between specific clinical risk factors and rtPA is associated with improved or poor functional ambulatory outcome in the multivariate analysis. We used odds ratios (ORs) to predict the odds of achieving a specific outcome in association with thrombolysis treatment in anti‐HTN therapy status. Odd ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of outcome measures were obtained using logistic regression, and significance level was set at the probability level of 0.05. We checked for multicollinearity and interactions among independent variables using Hosmer‐Lemeshow test. We used IBM SPSS v.24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for all our analysis.

3. RESULTS

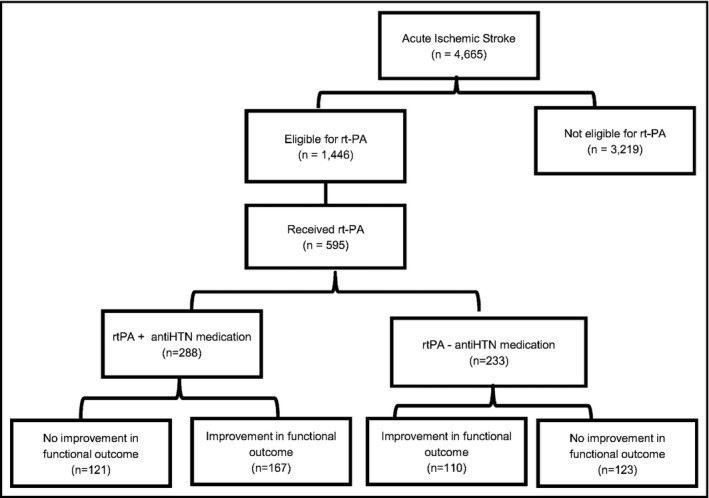

A total of 4665 ischemic stroke patients were identified. Of this population, 1446 patients were eligible for rtPA and 595 of these patients received rtPA. Of the 595 patients, 288 patients had a history of anti‐HTN medication use and 233 were not treated with anti‐HTN (Figure 1). Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical variables of acute ischemic stroke patients that received thrombolysis therapy (rtPA group) or those that did not receive rtPA (no rtPA group). The rtPA group was younger (68.65 ± 13.7 vs 72.5 ± 13.4), included more males (51.5% vs 44.0%), and fewer females (48.5% vs 56.0%). The rtPA group had lower rates of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter (11.6% vs 27.2%) and were less likely to have had a previous stroke (25.2% vs 34.4%). The rtPA group also demonstrated lower rates of congestive heart failures (11.8% vs 19.5%) and carotid artery stenosis (4.1% vs 7.8%) but was more likely to have smoking history (27.0% vs 19.0%), and higher NIHSS scores (9.95 ± 6.6 vs 7.82 ± 6.8) prior to treatment. Lower levels of serum cholesterol (167.2 ± 50.6 mg/dL vs 178.2 ± 48.2 mg/dL) and creatinine concentrations (1.21 ± 1.16 mg/dL vs 1.38 ± 1.03 mg/dL) were recorded by the rtPA group when compared to the no rtPA group.

Figure 1.

Acute ischemic stroke patients with a history of anti‐HTN medication with or without thrombolysis therapy and with improved and non‐improved functional outcome

Table 1.

Characteristics of acute ischemic stroke patients

| Number of patients | No rtPA group | rtPA group | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 851 | 595 | ||

| Age group: No. (%), y | |||

| <50 | 37 (6.1) | 42 (7.6) | 0.001* |

| 50‐59 | 69 (11.4) | 78 (17.7) | |

| 60‐69 | 124 (20.5) | 103 (23.4) | |

| 70‐79 | 164 (27.2) | 105 (23.8) | |

| >80 | 210 (34.8) | 113 (25.6) | |

| Mean ± SD | 72.5 ± 13.4 | 68.65 ± 13.7 | <0.001* |

| Race: No. (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 477 (79.0) | 356 (80.7) | 0.345 |

| African‐American | 117 (19.4) | 82 (18.6) | |

| Other | 10 (1.7) | 3 (0.7) | |

| Gender: No. (%) | |||

| Male | 266 (44.0) | 227 (51.5) | 0.020* |

| Female | 338 (56.0) | 214 (48.5) | |

| Medical history: No. (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 572 (94.7) | 426 (96.6) | 0.174 |

| Coronary artery disease | 240 (39.7) | 161 (36.5) | 0.303 |

| Dyslipidemia | 366 (60.6) | 285 (64.6) | 0.196 |

| Atrial fib/flutter | 196 (32.5) | 91 (20.6) | <0.001* |

| Previous stroke | 208 (34.4) | 111 (25.2) | 0.001* |

| Previous TIA | 75 (12.4) | 53 (12.0) | 0.924 |

| Congestive heart failure | 118 (19.5) | 52 (11.8) | 0.001* |

| Carotid artery stenosis | 46 (7.6) | 18 (4.1) | 0.019* |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 53 (8.8) | 28 (6.3) | 0.161 |

| History of smoking | 115 (19.0) | 119 (27.0) | 0.003* |

| Diabetes | 219 (36.3) | 150 (34.0) | 0.471 |

| Medication history: No. (%) | |||

| Antiplatelet | 394 (65.2) | 267 (60.5) | 0.135 |

| Cholesterol reducer | 339 (56.1) | 269 (61.0) | 0.128 |

| Diabetes medication | 173 (28.6) | 128 (29.0) | 0.890 |

| Initial NIH Stroke Scale group: No. (%) | |||

| 0‐9 | 411 (68.0) | 255 (57.8) | 0.004* |

| 10‐14 | 70 (11.6) | 76 (17.2) | |

| 15‐20 | 68 (11.3) | 54 (12.2) | |

| 21‐25 | 55 (9.1) | 56 (12.7) | |

| Mean ± SD | 7.82 ± 6.8 | 9.95 ± 6.6 | 0.534 |

| Risk of mortality GWTG ischemic stroke | |||

| Mean ± SD | 5.34 ± 5.89 | 5.93 ± 6.02 | 0.823 |

| Lab values: Mean ± SD | |||

| Serum cholesterol (mg/dL) | 178.2 ± 48.2 | 167.6 ± 50.6 | 0.003* |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 153.8 ± 86.9 | 156.3 ± 96.4 | 0.649 |

| Serum creatine (mg/dL) | 1.38 ± 1.03 | 1.21 ± 1.16 | 0.009* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 153 ± 29 | 131 ± 29 | 0.368 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 85 ± 19 | 82 ± 20 | 0.081 |

Comparing the characteristics of rtPA and no rtPA groups. Continuous variables are represented as Mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups are made with a Student t test. Discrete variables are represented as Count (Percent Frequency), and comparisons between groups were made using Pearson’s chi‐squared.

*P < 0.05.

Clinical and demographic characteristics associated with the improvement and non‐improvement in rtPA with anti‐HTN and without anti‐HTN is presented in Table 2. In the rtPA with anti‐HTN group, few patients with CHF (7.4% vs 15.0%) had improved functional outcome. The anti‐HTN group with improved functional outcome recorded lower levels of serum cholesterol (158.2 ± 52.1 mg/dL vs 186.9 ± 44.4 mg/dL) and creatinine concentrations (1.09 ± 0.98 mg/dL vs 1.33 ± 1.06 mg/dL) when compared to the no anti‐HTN group. All other medical history factors of age, race, gender, medication history, initial NIHSS score, risk of mortality GWTG score, BP, and BMI were not significantly different in the anti‐HTN and no anti‐HTN groups.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics, medical history, and presenting symptoms of acute ischemic stroke patients in a population of rtPA group with anti‐HTN medications compared with rtPA group without anti‐HTN medication using functional ambulatory outcome for measurement

| Number of patients | rtPA with anti‐HTN | rtPA without anti‐HTN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not improved | Improved | P‐value | Not improved | Improved | P‐value | |

| 167 | 121 | 123 | 110 | |||

| Age group: No. (%), y | ||||||

| <50 | 16 (9.6) | 12 (9.9) | 0.660 | 15 (12.2) | 17 (15.5) | |

| 50‐59 | 26 (15.6) | 24 (19.8) | 14 (11.4) | 14 (12.7) | ||

| 60‐69 | 41 (24.6) | 28 (23.1) | 15 (12.2) | 7 (6.4) | ||

| 70‐79 | 34 (20.4) | 29 (24.0) | 3 (2.4) | 10 (9.1) | ||

| >80 | 50 (29.9) | 28 (23.1) | 5 (4.1) | 4 (3.6) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 69.56 ± 13.1 | 67.53 ± 14.0 | 0.214 | 57.63 ± 14.5 | 56.62 ± 16.0 | 0.734 |

| Race: No. (%) | ||||||

| Caucasian | 135 (80.8) | 98 (81.0) | 0.493 | 40 (32.5) | 42 (38.2) | 0.359 |

| African‐American | 32 (19.2) | 22 (18.2) | 10 (8.1) | 10 (9.1) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Gender: No. (%) | ||||||

| Male | 78 (46.7) | 60 (49.6) | 0.629 | 25 (20.3) | 36 (32.7) | 0.029 |

| Female | 89 (53.3) | 61 (50.4) | 27 (22.0) | 16 (14.5) | ||

| Medical history: No. (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 161 (96.4) | 120 (99.2) | 0.132 | 15 (12.2) | 17 (15.5) | 0.671 |

| Coronary artery disease | 62 (37.1) | 38 (31.4) | 0.314 | 7 (5.7) | 9 (8.2) | 0.587 |

| Dyslipidemia | 100 (59.9) | 77(63.6) | 0.518 | 16 (13.0) | 12 (10.9) | 0.377 |

| Atrial fib/flutter | 37 (22.2) | 23 (19.0) | 0.516 | 2 (1.6) | 2 (1.8) | 1.000 |

| Previous stroke | 37 (22.2) | 31 (25.6) | 0.494 | 7 (5.7) | 8 (7.3) | 0.780 |

| Previous TIA | 22 (73.3) | 8 (6.6) | 0.072 | 9 (7.3) | 6 (5.5) | 0.402 |

| Congestive heart failure | 25 (15.0) | 9 (7.4) | 0.051* | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0.315 |

| Carotid artery stenosis | 6 (3.6) | 8 (6.6) | 0.240 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) | 0.079 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 13 (7.8) | 9 (7.4) | 0.913 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) | 0.079 |

| History of smoking | 40 (24.0) | 36 (29.8) | 0.192 | 22 (17.9) | 24 (21.8) | 0.693 |

| Diabetes | 61 (36.5) | 40 (33.1) | 0.543 | 8 (6.5) | 5 (4.5) | 0.374 |

| Medication history: No. (%) | ||||||

| Antiplatelet | 89 (53.3) | 77 (63.6) | 0.080 | 12 (9.6) | 14 (12.7) | 0.651 |

| Cholesterol reducer | 97 (58.1) | 76 (62.8) | 0.419 | 9 (7.3) | 6 (5.5) | 0.402 |

| Diabetes medication | 55 (32.9) | 35 (28.9) | 0.469 | 4 (3.3) | 2 (1.8) | 0.400 |

| Initial NIH Stroke Scale group: No. (%) | ||||||

| 0‐9 | 89 (53.3) | 60 (49.6) | 0.308 | 36 (29.3) | 23 (20.9) | |

| 10‐14 | 31 (18.6) | 16 (13.2) | 7 (5.7) | 14 (12.7) | ||

| 15‐20 | 21 (12.6) | 23 (19.0) | 5 (4.1) | 10 (9.1) | ||

| 21‐25 | 26 (156) | 22 (18.2) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (4.5) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 10.36 ± 7.1 | 11.61 ± 6.8 | 0.132 | 8.17 ± 6.3 | 10.75 ± 6.7 | 0.045 |

| Risk of mortality GWTG ischemic stroke | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 6.67 ± 6.9 | 6.69 ± 6.2 | 0.974 | 4.227 ± 5.4 | 5.508 ± 4.7 | 0.206 |

| Lab values: Mean ± SD | ||||||

| Serum cholesterol (mg/dL) | 186.9 ± 44.4 | 158.2 ± 52.1 | 0.007* | 169.7 ± 52.4 | 176.9 ± 48.9 | 0.139 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 150.3 ± 80.9 | 149.4 ± 91.7 | 0.902 | 157.3 ± 92.7 | 163.3 ± 100.7 | 0.470 |

| Serum creatine (mg/dL) | 1.33 ± 1.06 | 1.09 ± 0.98 | 0.005* | 1.43 ± 1.01 | 1.32 ± 1.31 | 0.281 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 152 ± 27 | 130 ± 27 | 0.075 | 127 ± 30 | 130 ± 31 | 0.588 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 85 ± 17 | 80 ± 19 | 0.161 | 82 ± 22 | 80 ± 22 | 0.62 |

Continuous variables are represented as Mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups are made with a Student t test. Discrete variables are represented as Count (Percent Frequency), and comparisons between groups were made using Pearson’s chi‐squared.

*P < 0.05.

Following the use of multivariate analysis to adjust for the cofounding effects of non‐significant variables in the total population (Table 3), NIHSS score (OR = 1.159, 95% CI, 1.056‐1.273, P = 0.002) and history of atrial fibrillation (OR = 2.456, 95% CI, 1.330‐4.533, P = 0.004) were associated with the anti‐HTN group while history of previous stroke (OR = 0.504, 95% CI, 0.280‐0.907, P = 0.022) and risk of mortality GWTG score (OR = 0.840, 95% CI, 0.743‐0.950, P = 0.005) were associated with no anti‐HTN group. In the rtPA group with anti‐HTN medications (Table 4), NIHSS score (OR = 1.094, 95% CI, 1.094‐1.000, P = 0.005) was associated with improved ambulatory outcome while patients with CHF (OR = 0.385, 95% CI, 0.385‐0.159, P = 0.035) and patients with a history of previous TIA (OR = 0.302, 95% CI, 0.302‐0.113, P = 0.017) were more likely to be associated with poor functional outcome. In the rtPA group without anti‐HTN medication (Table 5), patients with lower NIHSS score (OR = 1.159, 95% CI, 1.056‐1.273, P = 0.002) may be associated with improved ambulatory outcome. Patients presenting with an increased Risk of Mortality GWTG (OR = 0.840, 95% CI, 0.743‐0.950, P = 0.005) and a previous history of stroke (OR = 0.504, 95% CI, 0.280‐0.907, P = 0.022) were more likely to be associated with poor ambulatory outcomes.

Table 3.

A stepwise regression model to determine clinical factors associated with functional outcome based on ambulatory activities in the total population of acute ischemic stroke with rtPA and with or without anti‐HTN medications

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 0.988 | 0.965 | 1.013 | 0.354 |

| BMI | 1.019 | 0.982 | 1.058 | 0.315 |

| NIH Stroke Scale | 1.159 | 1.056 | 1.273 | 0.002* |

| Risk of mortality GWTG | 0.840 | 0.743 | 0.950 | 0.005* |

| Gender | 0.635 | 0.371 | 1.086 | 0.097 |

| Race | 1.379 | 0.778 | 2.443 | 0.272 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.456 | 1.330 | 4.533 | 0.004* |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.242 | 0.696 | 2.216 | 0.463 |

| Carotid artery stenosis | 1.249 | 0.479 | 3.257 | 0.649 |

| Diabetes | 1.895 | 0.812 | 4.422 | 0.139 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.690 | 0.368 | 1.295 | 0.248 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.346 | 0.696 | 2.603 | 0.377 |

| Hypertension | 1.412 | 0.428 | 4.656 | 0.571 |

| Previous stroke | 0.504 | 0.280 | 0.907 | 0.022* |

| Previous TIA | 1.341 | 0.648 | 2.774 | 0.429 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.574 | 0.612 | 4.047 | 0.347 |

| History of smoking | 0.575 | 0.266 | 1.244 | 0.160 |

| Antiplatelet medication | 1.085 | 0.599 | 1.966 | 0.788 |

| Antihypertension medication | 1.019 | 0.537 | 1.934 | 0.954 |

| Cholesterol reducer | 0.560 | 0.222 | 1.416 | 0.221 |

| Antidiabetic medication | 0.988 | 0.965 | 1.013 | 0.354 |

| Total serum cholesterol | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.881 |

| Blood glucose levels | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.218 | 0.641 |

| Serum creatinine | 0.106 | 0.136 | 0.612 | 0.434 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.060 | 0.806 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.240 | 0.624 |

Positive B values (Adj, OR >1) denote variables more associated with anti‐HTN while negative B values (Adj. OR <1) denote variables more associated with no anti‐HTN. Multicollinearity and interactions among independent variables were checked. Hosmer‐Lemeshow test (P = 0.081), Cox & Snell (R 2 = 0.412), Classification table (overall correctly classified percentage = 82.3%) were applied to check the model fitness.

*P < 0.05.

Table 4.

A stepwise regression model to determine clinical factors associated with functional outcome in rtPA group with pretreatment with anti‐HTN medications

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 0.989 | 0.964 | 0.989 | 0.408 |

| BMI | 1.016 | 0.978 | 1.016 | 0.414 |

| NIH Stroke Scale | 1.094 | 1.000 | 1.094 | 0.050* |

| Risk of mortality GWTG | 0.940 | 0.846 | 0.940 | 0.256 |

| Gender | 0.888 | 0.510 | 0.888 | 0.674 |

| Race | 0.947 | 0.494 | 0.947 | 0.870 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.104 | 0.521 | 1.104 | 0.796 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.802 | 0.435 | 0.802 | 0.479 |

| Carotid artery stenosis | 3.150 | 0.830 | 3.150 | 0.092 |

| Diabetes | 1.658 | 0.500 | 1.658 | 0.408 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.022 | 0.533 | 1.022 | 0.948 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.385 | 0.159 | 0.385 | 0.035* |

| Hypertension | 4.814 | 0.482 | 4.814 | 0.181 |

| Previous stroke | 0.949 | 0.493 | 0.949 | 0.876 |

| Previous TIA | 0.302 | 0.113 | 0.302 | 0.017* |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.416 | 0.513 | 1.416 | 0.502 |

| History of smoking | 1.314 | 0.671 | 1.314 | 0.426 |

| Antiplatelet medication | 1.682 | 0.903 | 1.682 | 0.101 |

| Antihypertension medication | 0.967 | 0.484 | 0.967 | 0.925 |

| Cholesterol reducer | 0.505 | 0.152 | 0.505 | 0.266 |

| Antidiabetic medication | 0.989 | 0.964 | 0.989 | 0.408 |

| Total serum cholesterol | 0.001 | 0.262 | 0.003 | 0.609 |

| Blood glucose levels | 0.002 | 0.965 | 0.002 | 0.326 |

| Serum creatinine | 0.118 | 0.348 | 0.201 | 0.555 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.004 | 0.622 | 0.006 | 0.430 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.018 | 4.299 | 0.008 | 0.038 |

Positive B values (Adj, OR >1) denote variables more associated with improved functional outcome while negative B values (Adj. OR <1) denote variables more associated with poor functional; outcome. Multicollinearity and interactions among independent variables were checked. Multicollinearity and interactions among independent variables were checked. Hosmer‐Lemeshow test (P = 0.006), Cox & Snell (R 2 = 0.254), classification table (overall correctly classified percentage = 74.2%) were applied to check the model fitness.

*P < 0.05.

Table 5.

A stepwise regression model to determine clinical factors associated with functional outcome in rtPA group without anti‐HTN medications

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 0.988 | 0.965 | 1.013 | 0.354 |

| BMI | 1.019 | 0.982 | 1.058 | 0.315 |

| NIH Stroke Scale | 1.159 | 1.056 | 1.273 | 0.002* |

| Risk of mortality GWTG | 0.840 | 0.743 | 0.950 | 0.005* |

| Gender | 0.635 | 0.371 | 1.086 | 0.097 |

| Race | 1.379 | 0.778 | 2.443 | 0.272 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.456 | 2.330 | 2.933 | 0.104 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.242 | 0.696 | 2.216 | 0.463 |

| Carotid artery stenosis | 1.249 | 0.479 | 3.257 | 0.649 |

| Diabetes | 1.895 | 0.812 | 4.422 | 0.139 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.690 | 0.368 | 1.295 | 0.248 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.346 | 0.696 | 2.603 | 0.377 |

| Hypertension | 1.412 | 0.428 | 4.656 | 0.571 |

| Previous stroke | 0.504 | 0.280 | 0.907 | 0.022* |

| Previous TIA | 1.341 | 0.648 | 2.774 | 0.429 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.574 | 0.612 | 4.047 | 0.347 |

| History of smoking | 0.575 | 0.266 | 1.244 | 0.160 |

| Antiplatelet medication | 1.085 | 0.599 | 1.966 | 0.788 |

| Antihypertension medication | 1.019 | 0.537 | 1.934 | 0.954 |

| Cholesterol reducer | 0.560 | 0.222 | 1.416 | 0.221 |

| Antidiabetic medication | 0.988 | 0.965 | 1.013 | 0.354 |

| Total serum cholesterol | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.127 | 0.721 |

| Blood glucose levels | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.957 |

| Serum creatinine | 0.017 | 0.208 | 0.007 | 0.936 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.050 | 0.822 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.014 | 0.009 | 2.517 | 0.113 |

Positive B values (Adj, OR >1) denote variables more associated with improved functional outcome while negative B values (Adj. OR <1) denote variables more associated with poor functional; outcome. Multicollinearity and interactions among independent variables were checked. Hosmer‐Lemeshow test (P = 0.8235), Cox & Snell (R 2 = 0.165), classification table (overall correctly classified percentage = 68%) were applied to check the model fitness.

*P < 0.05.

4. DISCUSSION

The current study investigated the effect of specific baseline clinical risk factors on ambulatory outcomes in thrombolyzed ischemic stroke patients with treated hypertension. A major finding is that in the thrombolyzed anti‐HTN stroke group, NIHSS score was the only significant variable associated with improved ambulatory outcome while patients with CHF and those with history of previous TIA were likely to be associated with poor outcome. In the univariate analysis, the proportion with poor outcome among patients that received rtPA was higher than those with improved outcome. This finding might be associated with the different proportions of baseline characteristics between patients who received thrombolysis and those who did not.

In the univariate analysis, CHF was associated with poor outcomes in the rtPA with anti‐HTN group, and even an adjustment for all other covariates did not change the significance of poor outcomes. Indeed, one would expect the effect of anti‐HTN medications to be shown in BP status. However, this was not the case in the univariate analysis, and the adjustment for baseline severity did not reveal the effect of BP. We do not exclude the possibility that the variation in the BP may be associated with stroke severity, instead of a cause of poor functional ambulatory outcome. Congestive heart failure as a syndrome contributes to or worsens the associated underlying diseases such as hypertension and stroke.26, 28 Hypertension in our stroke population was treated and met acceptable criteria. Moreover, our stroke patients with treated hypertension were older. It is possible that they present CHF with previous TIA as major clinical risk factors at baseline compared with those without CHF or TIA.21, 29 This suggests that CHF and TIA are important baseline clinical risk factors that may alter the benefit of thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke with controlled hypertension.

From a clinical standpoint, how might CHF modify the response to thrombolytic therapy and contribute to the observed poor outcome? Since CHF is a major cause of cardio‐embolic stroke,30 it may also cause cerebral hypoperfusion and delayed cerebral blood flow. This may result in pharmacokinetic changes due to delayed circulation time that probably alters the distribution of thrombolytic agents. Consequently, this may have rendered thrombolysis treatment less effective in CHF patients who are experiencing acute ischemic stroke although with treated hypertension.31

Apart from the lowering of blood pressure to control hypertension by antihypertensive drugs, different antihypertensives exert a number of nonhemodynamic effects, such as regulating endothelial and vascular smooth muscle activities.32 Moreover, antihypertensives interact with the fibrinolysis system.33 It is possible that activities of antihypertensive agents could interfere with the fibrinolytic process and blunt or enhance the effect of thrombolysis therapy with respect to stroke treatment outcome. In addition, since the fibrinolytic system is significant in the pathogenesis of thromboembolic complications of hypertension, the possibility that special antihypertensives interfere with this system to improve or worsen thrombolysis outcome warrants future investigation.

We observed that patients with a history of previous TIA who received rtPA are more likely to be associated with poor ambulatory outcome. The history of an established TIA within the previous 3 months is not a formal contraindication for intravenous thrombolysis.21, 34, 35 However, the onset of TIA within 24 hours of stroke may result in poor outcome.36, 37 This might be applicable to our treated hypertensive stroke patients treated with rtPA. Since TIA could influence outcome after thrombolysis, it is also possible that some of the patients in our sample may have TIA which may not be visible on the CT scans, and the presentation of TIA may contribute to poor ambulatory outcome with thrombolysis therapy. Our finding also suggests the possibility that the combined effect of CHF and TIA could result in poor functional ambulatory outcome in our hypertensive treated acute ischemic stroke population. This finding has practical consequences suggesting that although acute ischemic stroke patients may receive anti‐HTN medication to treat hypertension, there is the possibility of poor functional outcome that may be associated with CHF and TIA as other clinical conditions apart from hypertension.

Our study has limitations. Although we used data from a well‐standardized stroke registry, our data were not randomized indicating the possibility of selection bias. In our analysis, we did not consider the different classes of antihypertensive medications and their differential effect on functional outcome. The relatively small groups of patients with treated hypertension did not increase the power of our analysis. The absence of pre‐stroke functional status (ie, pre‐stroke mRS) and post‐treatment NIH scores did not allow for pre‐ and post‐stroke comparison for ambulatory and NIH scores or mRS to be made. Ambulation as a tool for functional outcome in ischemic stroke has been validated23, 25, 38. In general, untreated hypertension in the acute stage of ischemic stroke may be associated with poor functional outcome. With treated hypertension, the specific clinical baseline characteristics that alter the efficacy of thrombolysis is not fully understood. A major contribution of the current study to existing literature is identification of the possible combined effect of CHF and previous TIA as a contraindication for thrombolysis in stroke patients with treated hypertension.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Acute stroke patients with antihypertensive medications who received thrombolysis had more improved functional outcome regardless of CHF or TIA, compared with unthrombolyzed patients with controlled hypertension. Variability in the baseline clinical risk factors may be a key independent predictor of clinical outcome, and the management of identified risk factors for this patient population is necessary to improve the benefits of thrombolysis therapy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors report no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

BB, TF, BA, JS, and TN designed the concept, experimental design while BB did the data analysis. TF, BJ, BA, and TIN critically revised the drafts read and approved the last version of this manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was performed with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Greenville Health System and the institutional Committee for Ethics. Being a retrospective data analysis with blinded data, no consent was needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the stroke unit of Greenville Health system for helping in the data collection.

Fleming T, Blum B, Averkamp B, Sullivan J, Nathaniel T. Effect of antihypertensive medications on thrombolysis therapy and outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:271–279. 10.1111/jch.13472

REFERENCES

- 1. Bath PM, Appleton JP, Krishnan K, Sprigg N. Blood pressure in acute stroke: to treat or not to treat: that is still the question. Stroke. 2018;49(7):1784‐1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang L, Yang J, Li LT, et al. Comparison of amlodipine versus other calcium channel blockers on blood pressure variability in hypertensive patients in China: a retrospective propensity score‐matched analysis. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(7):651‐660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boan AD, Lackland DT, Ovbiagele B. Lowering of blood pressure for recurrent stroke prevention. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2506‐2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanon O, Pequignot R, Seux ML, et al. Relationship between antihypertensive drug therapy and cognitive function in elderly hypertensive patients with memory complaints. J Hypertens. 2006;24(10):2101‐2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rabasseda X. Carvedilol: an effective antihypertensive drug with antiischemic/antioxidant cardioprotective properties. Drugs Today (Barc). 1998;34(11):905‐926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laowattana S, Oppenheimer SM. Protective effects of beta‐blockers in cerebrovascular disease. Neurology. 2007;68(7):509‐514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Law M, Morris J, Wald N. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta‐analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Selim M, Savitz S, Linfante I, Caplan L, Schlaug G. Effect of pre‐stroke use of ACE inhibitors on ischemic stroke severity. BMC Neurol. 2005;5(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fuentes B, Fernández‐Domínguez J, Ortega‐Casarrubios MÁ, SanJosé B, Martínez‐Sánchez P, Díez‐Tejedor E. Treatment with angiotensin receptor blockers before stroke could exert a favourable effect in acute cerebral infarction. J Hypertens. 2010;28(3):575‐581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Raedt S, Haentjens P, De Smedt A, et al. Pre‐stroke use of beta‐blockers does not affect ischaemic stroke severity and outcome. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(2):234‐240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koton S, Tanne D, Grossman E. Prestroke treatment with beta‐blockers for hypertension is not associated with severity and poor outcome in patients with ischemic stroke: data from a national stroke registry. J Hypertens. 2017;35(4):870‐876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gasecki D, Coca A, Cunha P, et al. Blood pressure in acute ischemic stroke: challenges in trial interpretation and clinical management: position of the ESH Working Group on Hypertension and the Brain. J Hypertens. 2018;36(6):1212‐1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pocovi Natasha. Appraisal of clinical practice guideline: 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Physiother. 2018;64(3):199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiomar S, Patarroyo F, Anderson C. Blood pressure lowering in acute phase of stroke: latest evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2012;3(4):163‐171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turcato G, Cervellin G, Cappellari M, et al. Early function decline after ischemic stroke can be predicted by a nomogram based on age, use of thrombolysis, RDW and NIHSS score at admission. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43(3):394‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Adams H, Davis P, Leira E, et al. Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology. 1999;53(1):126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahmed N, Wahlgren N, Brainin M, et al. Relationship of blood pressure, antihypertensive therapy, and outcome in ischemic stroke treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2442‐2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bohannon RW, Horton MG, Wikholm JB. Importance of four variables of walking to patients with stroke. Int J Rehabil Res. 1991;14(3):246‐250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nathaniel TI, Gainey J, Blum B, Montgomery C, Ervin L, Madeline L. Clinical risk factors in thrombolysis therapy: telestroke versus nontelestroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(9):2524‐2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumar D, Gubbi J, Yan B, Palaniswami M. Motor recovery monitoring in post acute stroke patients using wireless accelerometer and cross‐correlation. . 35th Annual International Conference of the Ieee Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Conference Proceedings. 2013:6703‐6706. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Nathaniel TI, Cochran T, Chaves J, et al. Co‐morbid conditions in use of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt‐PA) for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Brain Inj. 2016;30(10):1261‐1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Winkel P, Bath PM, Gluud C, et al. Statistical analysis plan for the EuroHYP‐1 trial: European multicentre, randomised, phase III clinical trial of the therapeutic hypothermia plus best medical treatment versus best medical treatment alone for acute ischaemic stroke. Trials. 2017;18(1):573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lawson TR, Brown IE, Westerkam DL, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (rt‐PA) in acute ischemic stroke: outcomes associated with ambulation. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2015;33(3):301‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gainey J, Brechtel L, Konklin S, et al. In a stroke cohort with incident hypertension; are more women than men likely to be excluded from recombinant tissue‐type plasminogen activator (rtPA)? J Neurol Sci. 2018;387:139‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gainey J, Brecthtel J, Blum B, et al. Functional outcome measures of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator‐treated stroke patients in the telestroke technology. J Exp Neurosci. 2018;12:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fazzone B, Morris G, Black LA, et al. Exclusion and inclusion criteria for thrombolytic therapy in an ischemic stroke. Population.e 4(2): 1112. J Neurol Disord Strok. 2016;4(2):1‐5. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fredwall M, Sternberg S, Blackhurst D, Lee A, Leacock R, Nathaniel TI. Gender differences in exclusion criteria for recombinant tissue‐type plasminogen activator. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(11):2569‐2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Padjen V, Bodenant M, Jovanovic DR, et al. Outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation after intravenous thrombolysis for cerebral ischaemia. J Neurol. 2013;260(12):3049‐3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frank B, Fulton R, Weimar C, Shuaib A, Lees KR, Collaborators V. Impact of atrial fibrillation on outcome in thrombolyzed patients with stroke evidence from the virtual international stroke trials archive (VISTA). Stroke. 2012;43(7):1872‐1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pullicino P, Thompson J, Barton B, et al. Warfarin versus aspirin in patients with reduced cardiac ejection fraction (WARCEF): rationale, objectives, and design. J Cardiac Fail. 2006;12(1):39‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abdul‐Rahim AH, Fulton RL, Frank B, McMurray J, Lees KR, Collaborators V. Associations of chronic heart failure with outcome in acute ischaemic stroke patients who received systemic thrombolysis: analysis from VISTA. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(1):163‐169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lip G, Blann AD. Antihypertensive drug treatment and fibrinolytic function. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11(10):1266‐1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mirowsky JE, Carraway MS, Dhingra R, et al. Ozone exposure is associated with acute changes in inflammation, fibrinolysis, and endothelial cell function in coronary artery disease patients. Environ Health. 2017;16(1):126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sobolewski P, Brola W, Wiszniewska M, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with rt‐PA for acute ischemic stroke within 24 h of a transient ischemic attack. J Neurol Sci. 2014;340(1–2):44‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nathaniel IT, Gainey J, Blum B, Montgomery C. Clinical risk factors in thrombolysis therapy: telestroke versus nontelestroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(9):2524‐2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Akijian L, Ni Chroinin D, Callaly E, et al. Why do transient ischemic attack patients have higher early stroke recurrence risk than those with ischemic stroke? Influence of patient behavior and other risk factors in the North Dublin Population Stroke Study. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(1):96‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tursunov D, Akbarkhodjaeva Z. Risk factors of developing transient ischemic attack. J Neurol Sci. 2017;381:1115. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gainey J, Blum B, Bowie B, et al. Stroke with dyslipidemia: clinical risk factors in the telestroke versus non‐telestroke. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;4(87):123‐148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]