Abstract

A 77-year-old woman presented with a 2-week history of malaise, prostration, anorexia, abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhoea. She had been taking systemic corticosteroids for the past year. During hospitalisation, renal insufficiency, ionic changes and liver function abnormalities were detected and corrected. However, the patient developed total dysphagia. UGE revealed multiple shallow ulcers below the cricopharyngeal level and in the distal oesophagus, with normal-appearing intervening mucosa. Histological examination allowed the diagnosis of herpes simplex virus esophagitis. Treatment with intravenous acyclovir was instituted for 14 days. In the elderly, herpetic esophagitis may present with non-specific complains, such as prostration or anorexia. In the reported case, dysphagia was only detected as a late symptom, addressing the importance of maintaining a high degree of suspicion for the diagnosis of herpes simplex virus esophagitis.

Keywords: infection (gastroenterology), ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology, geriatric medicine

Background

This case highlights herpes simplex virus (HSV) as a rare, but important cause of oesophageal dysphagia. Herpetic esophagitis in the elderly can course with non-specific complains as malaise or prostration, sometimes attributed to dehydration, ionic imbalance and renal insufficiency. The diagnosis can be challenging and a high degree of suspicion is necessary when facing elderly patients with oesophageal dysphagia.

Case presentation

A 77-year-old woman, previously autonomous in daily-life activities, presented to the hospital with a 2-week history of malaise, prostration, fatigue, anorexia, myalgia, occasional episodes of abdominal pain and one episode of diarrhoea and vomiting. Her medical history included arterial hypertension, cardiac heart failure and gout, for which she had been taking low dose systemic corticosteroids for the past year, and a urinary tract infection diagnosed 6 days before and medicated with cefuroxime 500 mg twice a day.

Physical examination was remarkable for hypotension and signs of dehydration.

Investigations

Laboratory investigation showed a white blood cell count of 5.600/L with 83.6% neutrophils, c-reactive protein 0.40 mg/dL, a mild deterioration of renal function (creatinine 1.23 mg/dL, urea 122 mg/dL) and ionic changes, with hyponatremia (Na +113 mmol/L) and hypokalaemia (K+2.53 mmol/L). Liver function was also abnormal: total bilirubin 3.73 mg/dL with conjugated bilirubin 1 mg/dL, aspartate transaminase 128 mg/dL, alanine transaminase 158 mg/dL, gamma-glutamyl transferase 78 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 163 U/L and INR 1.2. Serological tests for HIV type 1 an 2, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and cytomegalovirus were negative and Epstein-Barr virus serology revealed a past infection.

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a 7 mm cyst on the head of the pancreas, with no other changes.

During hospitalisation, renal function improved and ionic changes were corrected. The patient was more reactive and odynophagia and total dysphagia were observed, requiring nasogastric intubation and feeding on fourth day of hospitalisation, presenting a level 1 of Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS),1 complicated by aspiration pneumonia.

An otorhinolaryngology consultation was requested and the patient was submitted to fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) on sixth day of hospitalisation that revealed mild pooling of secretions in the hypopharynx (figure 1), absence of reaction to laryngeal sensibility stimulation, pharyngeal delay, premature spillage and aspiration before whiteout (Penetration Aspiration Scale score 6) for liquids thickened according to levels 2 (mildly thick) and 3 (moderately thick) of International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) (figure 2).2

Figure 1.

Normal laryngeal anatomy with mild pooling of secretions in the hypopharynx.

Figure 2.

FEES showing aspiration before whiteout, PAS score 6, for liquids IDDSI level 3. FEES, fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing; IDDSI, International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative; PAS, Penetration Aspiration Scale.

Neck and chest CT was performed on the 10th day of hospitalisation and excluded structural esophageal abnormalities.

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE) was performed on the 11th day of hospitalisation revealing multiple shallow ulcers, some of them with raised edges, below the cricopharyngeal level (figure 3) and in the distal oesophagus (figure 4), with normal-appearing intervening mucosa, and exudate in the distal oesophagus. The histologic examination of oesophageal biopsies revealed epithelial cells with eosinophilic inclusions (Cowdry type A inclusion bodies) (figure 5). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the infection by HSV types 1 and 2 (figure 6).

Figure 3.

Shallow ulcers in proximal oesophagus.

Figure 4.

Shallow ulcers in distal oesophagus.

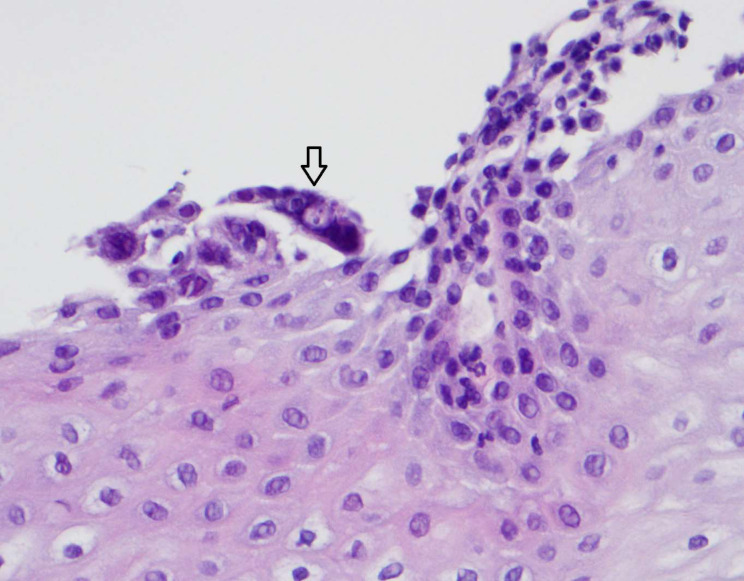

Figure 5.

H&E stain showing multinucleated giant cells and intranuclear inclusion bodies in epithelial cells, magnification 400x.

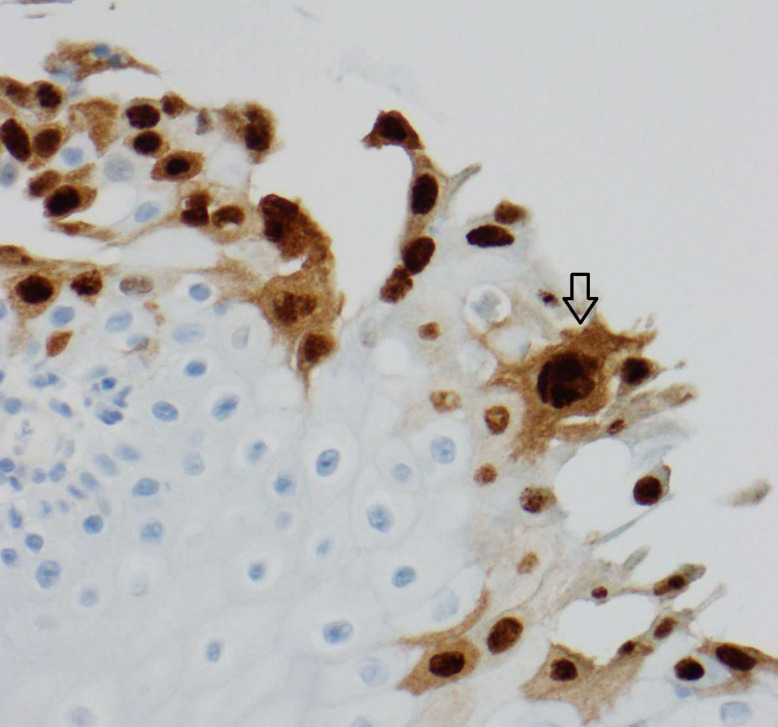

Figure 6.

Positive immunohistochemistry for HSV types 1 and 2, magnification 400x. HSV, herpes simplex virus.

Differential diagnosis

At first, patient’s initial complaints were attributed to ionic changes abnormalities. However, when these were corrected and patient became more reactive, odynophagia and total dysphagia were then noted.

To rule out oropharyngeal dysphagia, the patient was first examined by an otorhinolaryngologist. As FEES confirmed total dysphagia with impaired efficacy and safety of swallowing (lack of laryngeal sensibility and laryngeal aspiration in a patient previously non-dysphagic) which was not explained by an upper aerodigestive cause, gastroenterologist examination was also requested to rule out oesophageal dysphagia.

Total dysphagia can occur as a consequence of neoplastic formation in the aerodigestive tract, or nearby structures that cause oesophageal compression. It can also be caused by structural alterations in the aerodigestive tract (eg, oesophageal strictures). These pathologies were ruled out with complete otorhinolaringologist observation, FEES and UGE, in association with neck and chest CT.

Food bolus impaction can be related with total dysphagia. However, symptoms are usually acute and located.

Autoimmune disease can be responsible for dysphagia. However, the patient had no previous history suggesting the diagnosis, such as arthritis, renal function abnormalities (before the hospitalisation), or upper or lower respiratory tract pathology.

Infectious diseases of pharynx, larynx or oesophagus are another cause of total dysphagia, frequently with odynophagia. In this case, UGE with oesophageal biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of herpetic esophagitis.

Treatment

Herpetic esophagitis was assumed and intravenous acyclovir started (5 mg/kg every 8 hours intravenous for 14 days), with clinical improvement.

Outcome and follow-up

Besides the improvement in global health status, liver enzymes progressively normalised after treatment with acyclovir was started.

FEES was repeated 7 days after she had completed the treatment with acyclovir. There was a mild pharyngeal delay, an improvement of larynx sensibility and no efficiency or security changes of swallowing.

In food trials, the patient presented a good tolerance to food with IDDSI level 6 (soft consistency and bite-sized) and liquids IDDSI level 2 (mildly thick). The patient evolved from level 1 to 5 in FOIS scale. The nasogastric tube was removed and the oral feeding restarted with nutritionist support.

Discussion

HSV is the second most frequent cause of infectious esophagitis, after Candida albicans.

The disease can be caused by a primary infection or, more frequently by viral reactivation of a latent infection.3 Although it is more common in immunocompromised patients, there are some reports of HSV esophagitis in immunocompetent patients.3 4 HIV infection, organ transplantation, underlying malignancies and treatment with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunosuppressive agents or systemic corticosteroids are considered important risk factors for HSV esophagitis.5 The most common presenting symptoms of HSV esophagitis are odynophagia (34.8%–42.6%), dysphagia (30.4%–42.6%) and gastrointestinal bleeding (13%–31%). Other possible initial symptoms are fever, nausea or vomiting, retrosternal or epigastric pain.6 7 In immunocompetent patients, oral lesions of herpes simplex infection are visible in 21.1% of the patients and could appear before, during or after the onset of odynophagia.8

The diagnosis of HSV esophagitis is suspected based on endoscopic findings during upper endoscopy and confirmed by histopathological examination of the biopsied oesophageal lesions. Immunohistochemical staining for HSV glycoproteins can also be useful to confirm the diagnosis.

The endoscopic findings vary over time. In the early stages of the infection, small vesicles are visible. Then, there is a coalescence of the vesicles into larger lesions (0.5–2 cm) with raised borders and yellow/grey base, so-called volcano ulcers.9 10 Finally, there is a coalesce of the ulcers to form larger areas of ulceration and occasionally pseudomembranous esophagitis.11 Superficial non-ulcerated erythematous esophagitis and friable mucosa could also be observed.6 7 11 Regarding endoscopic location, most patients revealed oesophageal lesions in the middle to distal oesophagus, but the entire oesophagus can be involved.6 7 The upper third of the oesophagus is seldom involved in HSV esophagitis.6 7 Diagnostic histological features based on staining with H&E include large, red intranuclear inclusion bodies (Cowdry A intranuclear inclusions), multinucleated giant cells with groundglass nuclei in epithelial cells and margination of chromatin.10 Biopsies should be done at the margins instead of the base of oesophageal ulcers, once the biopsies at the base of the ulcers are generally inadequate for the diagnosis.10 The management of HSV esophagitis depends on host’s underlying immune status. Oral acyclovir (400 mg five times a day, for 2–3 weeks) is the established treatment for immunocompromised patients with HSV esophagitis; however, in the immunocompetent host, treatment is still controversial, as spontaneous resolution usually occurs after 1–2 weeks. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that a short course of oral acyclovir (200 mg five times a day or 400 mg three times a day, for 1–2 weeks) shortens the healing time and prevent complications in the immunocompetent host.4 In cases of severe odynophagia or dysphagia, intravenous acyclovir (5 mg/kg three times a day) can be administered for 1–2 weeks.12

Complications are rare and, generally, HSV esophagitis caries a good prognosis. However, gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, strictures, tracheoesophageal fistula and HSV pneumonia have been reported.10

Regarding the clinical case, advanced age, systemic corticosteroids administration and recent urinary tract infection are factors that may have contributed to the development of HSV esophagitis.

The initial symptomatology was non-specific and there were no facial or oropharyngeal lesions suggestive of HSV infection. Refusal to feed was primarily interpreted as part of reactive depression to a recent loss of a family member, and dysphagia was only detected on fourth day of hospitalisation. Therefore, the authors highlight that in the elderly presenting with herpetic esophagitis, non-specific complains, such as prostration or anorexia can be the main symptoms leading to medical assistance, while dysphagia can be a late symptom.

In this particular case, oesophageal lesions were mainly visible in the upper third of the oesophagus, just below the cricopharyngeal level, an atypical location in HSV esophagitis. It is also important to emphasise that after the patient had completed the treatment with acyclovir, there was an improvement both of the dysphagia and also of the global health status of the patient, favouring the diagnosis of HSV esophagitis.

Learning points.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) esophagitis in the elderly and in the most fragile patients can course with non-specific complains as malaise or prostration, associated with dehydration, renal insufficiency and ionic changes.

HSV esophagitis is more common in immunocompromised patients, but there are some reports of HSV esophagitis in immunocompetent patients.

The most frequent presenting symptoms of HSV esophagitis are odynophagia, dysphagia and gastrointestinal bleeding.

In immunocompetent patients, only about 1/5 of the patients with HSV esophagitis present with oral lesions of herpes simplex infection.

Complications are rare and, generally, HSV esophagitis caries a good prognosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Martinha Chorão, Consultant Pathologist at Hospital Egas Moniz, for providing assistance and advice from the histological point of view; Professor Pedro Escada, Head of Department of Otorhinolaringology of Hospital Egas Moniz, for its contribution as an experienced reviewer of clinical cases and Dr David Nascimento, speech and language therapist of Hospital Egas Moniz, for its effort to complete the relevant clinical information in a speech and language therapist perspective.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the diagnosis and management of the clinical case. The article was written by SFC, with an important contribution of CF, FC and MZV.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Crary MA, Mann GDC, Groher ME. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:1516–20. 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, et al. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 1996;11:93–8. 10.1007/BF00417897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadayakkara DK, Candelaria A, Kwak YE, et al. Herpes simplex virus-2 esophagitis in a young immunocompetent adult. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2016;2016:1–3. 10.1155/2016/7603484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canalejo E, García Durán F, Cabello N, et al. Herpes esophagitis in healthy adults and adolescents: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 2010;89:204–10. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181e949ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Généreau T, Rozenberg F, Bouchaud O, et al. Herpes esophagitis: a comprehensive review. Clin Microbiol Infect 1997;3:397–407. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H-W, Kuo C-J, Lin W-R, et al. Clinical characteristics and manifestation of herpes esophagitis: one single-center experience in Taiwan. Medicine 2016;95:1–8. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoversten P, Kamboj AK, Wu T-T, et al. Variations in the clinical course of patients with herpes simplex virus esophagitis based on immunocompetence and presence of underlying esophageal disease. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:1893–900. 10.1007/s10620-019-05493-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramanathan J, Rammouni M, Baran J, et al. Herpes simplex virus esophagitis in the immunocompetent host: an overview. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:2171–6. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald GB, Sharma P, Hackman RC, et al. Esophageal infections in immunosuppressed patients after marrow transplantation. Gastroenterology 1985;88:1111–7. 10.1016/S0016-5085(85)80068-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baehr PH, McDonald GB. Esophageal infections: risk factors, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 1994;106:509–32. 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90613-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBane RD, Gross JB. Herpes esophagitis: clinical syndrome, endoscopic appearance, and diagnosis in 23 patients. Gastrointest Endosc 1991;37:600–3. 10.1016/S0016-5107(91)70862-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosołowski M, Kierzkiewicz M. Etiology, diagnosis and treatment of infectious esophagitis. Prz Gastroenterol 2013;8:333–7. 10.5114/pg.2013.39914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]