Abstract

Unconscious biases may influence clinical decision making, leading to diagnostic error. Anchoring bias occurs when a physician relies too heavily on the initial data received. We present a 57-year-old man with a 3-year history of unexplained right thigh pain who was referred to a physiatry clinic for suggestions on managing presumed non-organic pain. The patient had previously been assessed by numerous specialists and had undergone several imaging investigations, with no identifiable cause for his pain. Physical examination was challenging and there were several ‘yellow flags’ on history. A thorough reconsideration of the possible diagnoses led to the discovery of hip synovial osteochondromatosis as the cause for his symptoms. Over-reliance on the referral information may have led to this diagnosis being missed. In patients with unexplained pain, it is important to be aware of anchoring bias in order to avoid missing rare diagnoses.

Keywords: musculoskeletal syndromes, degenerative joint disease, medical education, orthopaedics, rehabilitation medicine

Background

Synovial osteochondromatosis (SOC) is an uncommon condition characterised by metaplasia and fragmentation of the synovium within a joint cavity.1–3 Ossification of these synovial fragments occurs in approximately 60%–95% of cases.4 5 The knee is the most frequently affected joint, followed by the elbow, hip and then ankle.1 SOC has been reported to occur in 1.8 per million individuals annually in England.1 There appears to be a male predilection, in a 3:1 ratio to females.5 SOC generally arises in the third to fifth decade.1 It may present with joint swelling, pain, locking or reduced range of motion (ROM).1 Unfortunately, many times symptoms are non-specific and insidious, causing difficulty in detecting the condition.1 Patients also often present with multiple normal plain radiographs,6 making it even more challenging to diagnose SOC. One systematic review suggested that patients had symptoms for an average of 5 years before a diagnosis was made.7 If left untreated, SOC may cause secondary osteoarthritis (OA). As such, early diagnosis is important not only for reducing patient symptom burden but also in order to preserve the health of the involved joint.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old man with a 3-year history of unexplained right thigh pain was referred to an outpatient physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) clinic for chronic pain management. He had previously been evaluated by his family physician, a spinal orthopaedic surgeon, a sports medicine orthopaedic surgeon and a vascular surgeon. He had undergone radiographs of the lumbar spine, pelvis and right hip; a magnetic resonance (MR) arthrogram of the right hip; and ankle-brachial indices. A pain generator had not yet been identified. His medical history was significant for well-managed hypothyroidism. His prescribed medications included levothyroxine 200 mcg daily and codeine contin 300 mg two times a day. Due to the intensity of his pain, he had been taking a higher dose of codeine contin at 300 mg three times a day. The patient described the pain as aching and diffuse, located throughout the right proximal thigh. The pain had been gradual in onset and progressive. It was worse with weight-bearing. The patient endorsed right hip stiffness with no locking or catching. He also reported pain-related weakness, having to passively lift his right thigh for transfers. The patient denied numbness, paresthesiae, radicular symptoms, claudication, falls, a change in bowel or bladder function, fevers or chills. He had trialled oral ibuprofen, cyclobenzaprine, gabapentin, pregabalin, hydromorphone, oxycodone and transdermal buprenorphine without benefit. He had also tried right L3/4 and L4/5 facet joint injections, a right L4 nerve root epidural steroid injection, a right intra-articular hip injection and a right greater trochanteric bursa injection without effect.

On physical examination, lower extremity bulk, tone and deep tendon reflexes were normal. Plantar responses were downgoing. Strength examination is shown in table 1. Sensation to light touch and pinprick were normal.

Table 1.

Medical Research Council (MRC) manual muscle testing scores for the lower limbs

| Movement tested | Strength (MRC) | |

| Right | Left | |

| Hip flexion* | 4+ | 5 |

| Hip extension* | 3 | 5 |

| Hip abduction* | 3 | 5 |

| Knee extension* | 4+ | 5 |

| Knee flexion | 5 | 5 |

| Ankle dorsiflexion | 5 | 5 |

| Ankle plantar flexion | 5 | 5 |

| Ankle inversion | 5 | 5 |

| Ankle eversion | 5 | 5 |

| Extensor hallucis longus | 5 | 5 |

*Painful.

The patient was tender over the proximal right rectus femoris and iliopsoas tendons and at the true hip joint. There was no tenderness of the lumbar spine, lateral or posterior thigh structures or knee. Passive right hip flexion was limited to 50°, internal rotation to 0° and external rotation to 0° with significant pain and soft end-feel in all planes. There was full passive ROM of the right knee and ankle. Special tests for hip pathology were limited by kinesiophobia. The patient ambulated with a four-point cane in a step-to fashion, leading with the left foot. Throughout the gait cycle, the right hip was in 20° of flexion, and there was right-sided antalgia.

Investigations

Two years prior to presentation, the patient had had an unremarkable right hip MR arthrogram (figure 1). One year prior to presentation, the patient had had an unremarkable MR of the lumbar spine. Although the patient’s right hip radiographs 17 months prior (figure 2A) had been normal, given the reduction in right hip ROM on physical examination, and the challenges with performing an adequate exam, we elected to repeat these radiographs to be complete (figure 2B, C). The new radiographs illustrated medial joint space narrowing and multiple calcified intra-articular loose bodies, consistent with SOC. A right hip CT scan (figure 3) was later obtained for preoperative planning, and revealed similar findings.

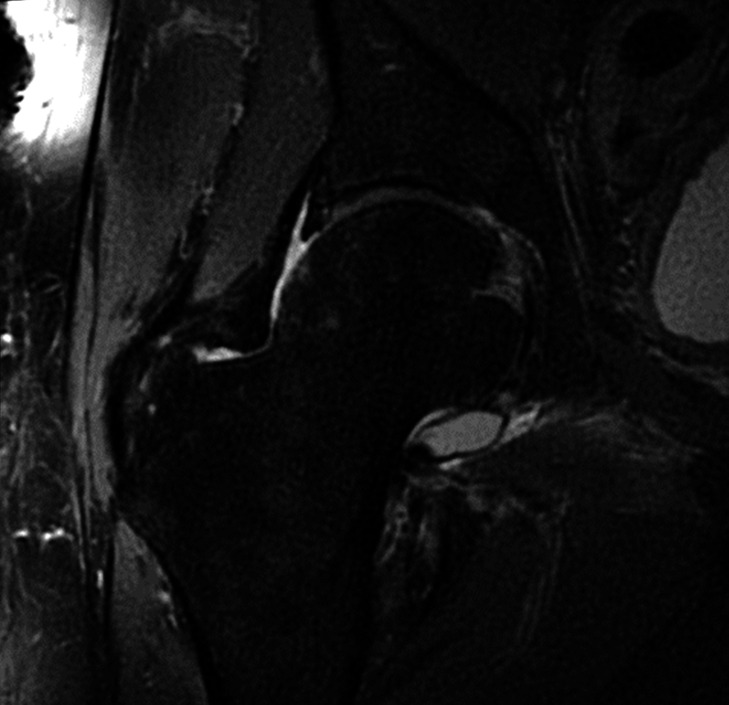

Figure 1.

A coronal T2-weighted fat-saturated magnetic resonance arthrogram image of the right hip performed 22 months prior to presentation at the physical medicine and rehabilitation clinic was normal, with no evidence of synovial osteochondromatosis.

Figure 2.

(A) An anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis 17 months prior to PM&R clinic presentation showed no right hip intra-articular abnormalities. Subsequent (B) anteroposterior pelvis and (C) right lateral hip radiographs performed after the patient was assessed by physical medicine and rehabilitation showed multiple calcified intra-articular loose bodies, consistent with synovial osteochondromatosis (SOC). A delay in radiographic appearance of ossified loose bodies is a common feature in SOC.

Figure 3.

CT reconstruction of the (A) posterior and (B) anterior pelvis showed numerous osseous loose bodies within the right hip joint, consistent with synovial osteochondromatosis.

Treatment

The patient was counselled on a more appropriate assisted ambulation technique and on his opioid use. After the hip radiographs were performed, he was referred for a total hip arthroplasty, given his age and concomitant OA. The femoral head that was removed intra-operatively showed a large defect measuring 3.5 by 1.9 cm. There were also multiple smooth ossific fragments in the synovium and surrounding soft tissues ranging from 0.2 to 1.0 cm in diameter.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient declined PM&R follow-up postoperatively, although he consented for his case to be presented for educational purposes.

Discussion

Physicians often grapple with unconscious cognitive biases that may lead to diagnostic inaccuracy.8 9 When examining diagnostic errors within a veterans affairs hospital and private healthcare system, Singh et al found that 79% of errors occurred due to cognitive bias.10 The anchoring effect refers to the cognitive bias where a physician or medical learner over-relies on pre-existing information to guide subsequent clinical judgements.11 The anchoring bias may be at play in anywhere from 6% to 88% of all cognitive biases leading to diagnostic error seen in trainees and practicing physicians.8 Prior to our evaluation, this patient had seen several specialists and undergone many investigations without an identifiable aetiology for his pain. In addition, in the chronic pain literature, ‘yellow flags’ refer to risk factors for prolonged disability in a patient with musculoskeletal symptoms.12 This patient had several yellow flags, including the use of opioids outside of recommended guidelines, trialling several pharmacological and interventional pain management strategies without benefit and features of pain catastrophisation and kinesiophobia.12 The pre-existing information from prior consultants, prior extensive normal imaging, failure to respond to multiple injections and presence of yellow flags seemed to initially steer our team to ‘anchor on’ to the diagnosis of a patient with no organic pathology, as had been implied in the referral letter. However, metacognition, or the awareness of one’s thought processes,9 was helpful in mitigating the risk of anchoring bias in this case. By asking ourselves questions like, ‘What else this could be?’ and ‘Why are we pursuing the diagnosis of non-organic pathology?’, we were able to entertain alternative diagnoses,13 leading us to order a repeat a hip radiograph despite multiple prior normal hip imaging tests.

In our patient’s case, the delay in diagnosis, which is common in SOC7 due to its often insidious presentation1 and often initially normal radiographs,6 led to both central and peripheral sensitisation, which are common phenomena of chronic nociceptive pain.14 Our patient developed depression and significant limitations in performing his activities of daily living due to his prolonged unexplained pain, which are also common outcomes in patients with chronic pain.15 Perhaps an earlier diagnosis may have mitigated the risk of some of these complications. Physicians, residents and medical students should be aware of how anchoring bias may affect their pursuit of a wider differential diagnosis and resultant medical work-up for a presenting issue. Ultimately, in this case, a repeat physical examination and the use of metacognition to counteract anchoring bias were crucial in identifying the rare and unexpected diagnosis of SOC.

Patient’s perspective.

My condition developed over 4 years before it was diagnosed. With modern technology and tests available it should not have taken 4 years to diagnose. I was continually passed back and forth between specialists like a hot potato over a period of 4 years. The condition worsened to the point where I could not function day to day. I was in extreme pain and could not sit, stand or walk for any length of time. My leg became extremely sensitive to the lightest touch. If our cat brushed up against my leg it sent searing pain up my body. I could not work, drive, watch a movie or enjoy life at all. Pain was my constant companion.

This condition has affected my entire life. Once my hip was replaced the pain lessened. Due to the long time it took to be diagnosed, it is now taking a long time for rehabilitation. I still walk with a limp and have some residual pain. If this had been diagnosed sooner and the hip replacement done, it’s possible my recovery would have been a lot shorter. I feel I suffered needlessly while the doctors passed me around trying to decide what to do.

Learning points.

Synovial osteochondromatosis may present with non-specific and insidious symptoms, causing difficulty in detecting the condition.

It may take 1-3 years for synovial osteochondromatosis to appear on radiographs.

Anchoring bias refers to over-reliance on received pre-existing information. It is common in physicians and medical trainees.

Reflecting on one’s potential for anchoring bias may help the clinician pursue a wider differential diagnosis.

Footnotes

Twitter: @mobilitybetter

Contributors: RHKM conceived of this case report. RHKM and RM critically reviewed the literature and drafted and revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work if questions arise related to its accuracy or integrity.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Neumann JA, Garrigues GE, Brigman BE, et al. Synovial chondromatosis. JBJS Rev 2016;4:e2:1–7. 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.O.00054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Chetrit E, Applbaum YH. Synovial osteochondromatosis of the hip. J Rheumatol 2010;37:668–9. 10.3899/jrheum.090762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko E, Mortimer E, Fraire AE. Extraarticular synovial chondromatosis: review of epidemiology, imaging studies, microscopy and pathogenesis, with a report of an additional case in a child. Int J Surg Pathol 2004;12:273–80. 10.1177/106689690401200311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helms C. Malignant tumors. : Fundamentals of skeletal radiology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2013: 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC, et al. Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2007;27:1465–88. 10.1148/rg.275075116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox C, Hull R, Langdown A. 7. Synovial Chondromatosis: A Diagnosis to Consider in Persistent Hip Disease with Normal Plain X-Rays. Rheumatology 2014;53:i59. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu096.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trias A, Quintana O. Synovial chondrometaplasia: review of world literature and a study of 18 Canadian cases. Can J Surg 1976;19:151–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, et al. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:1–14. 10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2018;48:225–32. 10.4997/JRCPE.2018.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AND, et al. Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:418–25. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aguirre LE, Chueng T, Lorio M, et al. Anchoring bias, Lyme disease, and the diagnosis conundrum. Cureus 2019;11:e4300. 10.7759/cureus.4300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, et al. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors ("yellow flags") in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther 2011;91:737–53. 10.2522/ptj.20100224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med 2003;78:775–80. 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pak DJ, Yong RJ, Kaye AD, et al. Chronification of pain: mechanisms, current understanding, and clinical implications. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2018;22:9. 10.1007/s11916-018-0666-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawai K, Kawai AT, Wollan P, et al. Adverse impacts of chronic pain on health-related quality of life, work productivity, depression and anxiety in a community-based study. Fam Pract 2017;34:656–61. 10.1093/fampra/cmx034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]