Abstract

This was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, parallel‐group, double‐blind dose‐ranging study. Hypertensive adults (n=555) received one of five doses of azilsartan (AZL; 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 mg), olmesartan medoxomil (OLM) 20 mg, or placebo once daily. The primary endpoint was change in trough clinic diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at week 8. Compared with placebo, all AZL doses (except 2.5 mg) provided statistically and clinically significant reductions in DBP and systolic blood pressure (SBP) based on both clinic blood pressure (BP) and 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM). AZL 40 mg was statistically superior vs OLM. Clinic BP was associated with a pronounced placebo effect (−6 mm Hg), whereas this was negligible with ABPM (±0.5 mm Hg). Adverse event frequency was similar in the AZL and placebo groups. Based on these and other findings, subsequent trials investigated the commercial AZL medoxomil tablet at doses 20 to 80 mg/d using 24‐hour ABPM.

Azilsartan (AZL) is an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) with potent blood pressure (BP)–lowering effects.1, 2 During its early clinical development as a treatment for hypertension, AZL was investigated using various formulations, including an AZL medoxomil (AZL‐M) prodrug capsule, an AZL‐M tablet, and an AZL (non‐prodrug) tablet.3 The AZL‐M prodrug is rapidly hydrolyzed during absorption in the gut to form AZL, which is the active moiety.1, 2 The AZL‐M capsule was not pursued into phase 3 because of a pronounced food effect that results in higher, but more variable, plasma exposure to AZL.3 Nevertheless, phase 2 dose‐ranging studies performed using the AZL‐M capsule and AZL tablet formulations provided the basis for dosing in subsequent phase 3 studies with the AZL‐M tablet (which is not affected by food).3 The bioavailability of AZL using the AZL‐M tablet is approximately 1.7 relative to the AZL‐M capsule and 0.6 relative to the AZL tablet in the fasted state.3

In the United States, Europe, and other countries, the AZL‐M tablet formulation is now approved for the treatment of hypertension at a dose of 20 to 80 mg ( #bib8 #bib9 #bib10 mg in the United States) once daily, alone or in combination with other antihypertensive agents.4, 5 A separate development program was pursued using the non‐prodrug formulation of AZL in Japan, where it is now available for clinical use.1, 2

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is being used increasingly in clinical trials.6 It has several advantages over conventional clinic‐based methods, as it provides repeated BP measurements over a 24‐hour period away from the medical environment and is generally not affected by placebo. Furthermore, with the use of ABPM, it is possible to detect and avoid confounding effects of both masked hypertension and white‐coat hypertension.6 Furthermore, compared with clinic measurements, ABPM (whether using mean 24‐hour, daytime, or nighttime values) is a better predictor of hypertension‐related target organ damage and cardiovascular death, such that a much smaller drop in ABPM may be required to provide an equivalent reduction in events.7 In spite of these advantages, use of ABPM is not an absolute requirement from regulatory bodies when evaluating the effect of drugs on BP (although it is recommended), and many studies still rely on clinic BP measurement as the primary measure of drug efficacy.6 The phase 3 program for AZL‐M was the first antihypertensive to use 24‐hour ABPM as the primary endpoint in key efficacy studies for US Food and Drug Administration approval and, therefore, ABPM results are included in the product labelling.4, 5, 8, 9, 10

The current article describes the BP‐lowering dose‐response relationship of the AZL tablet formulation (available in Japan) in patients with essential hypertension. Measurements were performed using both ABPM and conventional clinical methods, thus allowing a comparison of the two approaches. The phase 2 study evaluating the AZL‐M capsule will be published separately.

Research Design and Methods

Study Design

This was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, parallel group, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, dose‐ranging study consisting of a 7‐day screening period, a 14‐day single‐blind placebo run‐in, and 8 weeks of double‐blind treatment. The study was performed at 50 centers in the United States and Argentina, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The applicable institutional review boards or ethics committees approved the study and all patients gave written informed consent to participate.

Study Participants

The study population consisted of men and women aged 18 years and older with mild to moderate uncomplicated essential hypertension (DBP ≥95 and ≤114 mm Hg at the start of placebo run‐in and the randomization visit). For inclusion, participants were required to discontinue their current antihypertensive medication(s), if any #bib2 weeks before randomization. Clinical laboratory evaluations (including clinical chemistry, hematology, and complete urinalysis) had to be within the reference ranges for the testing laboratory.

The main exclusion criteria were SBP >180 mm Hg; a decrease of ≥8 mm Hg in clinic DBP between the start of the placebo run‐in and the randomization visit; hypersensitivity to ARBs; grade 3/4 hypertensive retinopathy; clinically relevant history of cardiovascular disease (eg, atrial fibrillation or flutter); secondary hypertension of any etiology; history of collagen vascular disorder within the past 5 years; night shift work; significant, moderate to severe renal dysfunction (confirmed by serum creatinine >2 mg/dL [180 μmol/L]) or renal disease; history of drug or alcohol abuse; history of cancer that had not been in remission for at least the past 5 years; type 1 or uncontrolled type 2 diabetes; alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate transaminase (AST) more than three times the upper limit of normal; active liver disease; or jaundice. Pregnant or lactating women were also excluded.

Excluded medications included diuretics, vasodilators, thiazolidinediones, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, phenothiazines, diet medications, amphetamines or their derivatives, chronic use of common cold medications, or nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, including aspirin >325 mg/d or cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors (except celecoxib, if dose is stable for ≥1 month prior to randomization).

Treatment Allocation

A centralized interactive voice‐activated response system was used for patient randomization and study medication assignments. Participants were randomized in equal ratios to receive double‐blind treatment with one of five dose levels of AZL (2.5 #bib5 #bib10 #bib20, or 40 mg), the reference treatment (OLM 20 mg), or placebo once per day in the morning with or without food for 8 weeks. The AZL study medication was supplied as 2.5, 5, and 10 mg tablets and corresponding placebo tablets; OLM was supplied as 20 mg over‐encapsulated (O/E) capsules with matching placebo capsules. Each dose was administered as a total of four tablets (ALZ and/or matching placebo) plus one OLM O/E or matching placebo capsule.

Endpoints and Assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in sitting trough clinic DBP from baseline to week 8. Secondary efficacy endpoints included sitting SBP (clinic), standing SBP and DBP (clinic), and SBP and DBP using 24‐hour ABPM. Safety variables included adverse events (AEs), clinical laboratory tests (hematology, serum chemistry, and urinalysis), vital signs, physical examination, electrocardiography results, and concomitant medications. All patients who received at least one dose of double‐blind study medication were included in the safety analysis.

Clinic BP measurements (two seated after 5 minutes of sitting and one standing after 2 minutes of standing) were taken approximately 24 hours after the previous dose and prior to dosing or blood collection on the day of study visits. Measurements were performed (using an appropriate cuff size) with either a standard mercury sphygmomanometer (the preferred method) or a certified automated (and calibrated) BP device. Devices designed to measure BP from the finger or wrist were not permitted. A printed BP report was obtained for each recording to minimize the potential for variability between operators.

Baseline ABPM was conducted in all patients at study day 1, and the patient was instructed to start double‐blind dosing the morning after 24‐hour ABPM was complete. A single follow‐up 24‐hour ABPM measurement was obtained at the final visit in all patients who completed more than 4 weeks of double‐blind treatment. For the follow‐up measurement (week 8 or final visit) the investigator administered the study drug in the clinic at 8 am (±2 hours) and prior to ABPM start. A core laboratory (Integrium, LLC, Tustin, CA) provided the portable ABPM units (Model 90207 ABP System; Spacelabs Healthcare, Snoqualmie, WA) with a hookup and data transfer instructions. The device was programmed and calibrated (for each patient) by the investigator or designee to measure BP and heart rate at set intervals during the day and night. Measurements were stored on the device and later uploaded onto a computer.

The ABPM studies were performed under similar circumstances on each occasion—if possible, the device was applied on the same day of the week and as close to the same time of day as feasible. For each ABPM evaluation, the patient reported to the clinic for device placement by 8 am±2 hours. An experienced technician tested the device for agreement with an appropriately calibrated sphygmomanometer using a t‐tube and stethoscope. The average of three simultaneous ABPM and sphygmomanometer diastolic BP measurements had to agree within 7 mm Hg.

The ABPM recorder was manually initiated and the device start time and time of the morning dose of study medication were recorded. During the monitoring period, a diary was provided to the patient with instructions to record bedtime, time of awakening, and arising, and any unusual technical occurrences (eg, failure of cuff to inflate). Times of sleep and awakening were also recorded in the ABPM software program to calculate the actual awake and sleep BP values.

The device was set to obtain readings every 15 minutes during the interval of 6 am to 10 pm (to coincide with the daytime, awake period) and every 20 minutes during the interval of 10 pm to 6 am (to coincide with the nighttime, sleeping period). The patient was encouraged to engage in their usual physical activity levels, but to avoid strenuous exercise during the monitoring period. In addition, sleeping during the daytime was to be avoided during the ABPM study period. During the actual BP measurements, the patient was instructed to hold their arm still and remain in place once cuff inflation began. An ABPM recording was considered adequate if: (1) the “beginning of test” time was between 6 am and 10 am, (2) the monitoring period was at least 24 hours in duration, (3) at least 70 valid readings were obtained (80% acceptance rate), and (4) no more than two nonconsecutive hours were missing a valid reading. If the recording did not meet these minimal quality‐control criteria, the ABPM recordings were repeated once within 3 days. Patients were instructed on the administration of the appropriate study medications, if a repeat ABPM was required.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis, tabulations of descriptive statistics, and inferential statistics were performed using SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All analyses were based on the intent‐to‐treat (ITT) population, defined as all patients who received at least one dose of double‐blind study medication after randomization. A patient was included in the analyses of a specific efficacy variable only when there was both a baseline value and at least one value during the double‐blind treatment period. Analysis of change from baseline was based on both observed values and a last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF) method.

Treatment group comparisons (active drug vs placebo or AZL vs OLM) for change from baseline in efficacy variables were carried out using a one‐way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with terms for treatment (as a factor) and baseline value (as a covariate) in the model. P values, least squares (LS) means, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for treatment differences in change from baseline were estimated within the framework of ANCOVA.

A sample size of 525 participants (75 per treatment group) was calculated as sufficient to have ≥80% power to detect a difference of 5 mm Hg in change from baseline DBP between the active and placebo treatment groups with a .05 two‐sided significance level, assuming a common standard deviation of 10 mm Hg and a 15% dropout rate.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 574 patients were randomized into the study (Figure S1). A total of 555 patients received double‐blind medication and were included in the safety analysis, with a further 28 patients excluded from the primary efficacy analysis because of a lack of postbaseline values.Demographic and baseline characteristics for the patient population were well matched between the different groups and are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the mean age was approximately 54 years, mean body weight was 88.7 kg, 78% were white, and there was a similar number of men and women. The mean baseline clinic trough BP was approximately 153/100 mm Hg. Mean baseline BP values based on ABPM were approximately 10 mm Hg lower during the daytime (awake) and 20 mm Hg lower during the nighttime (asleep) than trough clinic values.

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

| Demographic/Baseline Variable | Placebo (n=77) | AZL 2.5 mg (n=78) | AZL 5 mg (n=80) | AZL 10 mg (n=80) | AZL 20 mg (n=79) | AZL 40 mg (n=81) | OLM 20 mg (n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female/male, % | 55/45 | 59/41 | 49/51 | 50/50 | 52/48 | 49/51 | 56/44 |

| White/black/other race, % | 75/21/4 | 83/17/0 | 76/19/5b | 81/18/1 | 73/23/4 | 72/25/4 | 81/11/8 |

| Age, mean±SD, y | 54.9±9.3 | 54.9±12.0 | 53.9±11.4 | 52.6±10.8 | 55.2±12.4 | 52.7±9.9 | 54.1±11.8 |

| Body weight, mean±SD, kg | 85.6±18.4 | 90.7±21.6 | 86.1±19.6 | 90.6±20.5 | 85.0±15.8 | 94.7±20.1 | 88.0±18.3 |

| Sitting trough clinic BP, mean±SD, mm Hg | |||||||

| DBP | 99.7±3.8 | 100.6±5.2 | 100.5±4.2 | 100.0±4.0 | 101.3±5.7 | 101.3±4.3 | 100.1±3.9 |

| SBP | 152.2±12.4 | 153.4±13.1 | 152.9±12.3 | 151.2±12.6 | 154.4±13.9 | 153.2±12.0 | 152.4±13.2 |

| ABPM variables, mean±SD, mm Hg | |||||||

| 24‐h DBP | 86.8±9.5 | 87.6±8.8 | 87.3±11.6 | 87.4±10.5 | 87.9±10.6 | 88.2±10.0 | 85.9±10.3 |

| Daytime (awake) DBP | 89.7±9.6 | 91.2±9.2 | 90.4±11.8 | 90.5±10.6 | 91.0±10.4 | 91.5±9.9 | 89.0±10.8 |

| Nighttime (asleep) DBP | 78.7±9.8 | 78.2±10.0 | 79.1±12.0 | 79.2±12.3 | 79.1±11.9 | 78.8±11.9 | 77.5±10.9 |

| Trough DBPa | 90.6±10.7 | 92.1±10.9 | 91.5±14.6 | 91.1±11.0 | 90.9±12.5 | 91.7±12.3 | 89.9±13.3 |

| 24‐h SBP | 143.4±13.9 | 144.2±13.9 | 144.1±15.6 | 143.6±17.0 | 143.7±13.6 | 145.6±16.0 | 143.5±14.1 |

| Daytime (awake) SBP | 146.7±13.9 | 148.3±14.4 | 147.7±16.0 | 147.0±16.8 | 147.3±14.0 | 149.3±15.9 | 146.8±14.1 |

| Nighttime (asleep) SBP | 134.4±15.6 | 133.4±15.4 | 134.7±16.3 | 135.0±19.1 | 133.6±14.6 | 134.8±18.2 | 134.7±16.4 |

| Trough SBPa | 146.6±16.6 | 148.8±16.1 | 149.6±20.2 | 147.2±17.9 | 147.2±17.1 | 147.9±18.7 | 147.2±18.8 |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; AZL, azilsartan; BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; OLM, olmesartan medoxomil; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation. “Other” indicates Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander, or Multiracial. aTrough using the last 2 hours of the dosing interval. bIncluding two multiracial participants not otherwise classified.

A total of 491 patients (86% of randomized patients; 88% of patients receiving double‐blind medication) completed the study; the most common reasons for premature discontinuation were voluntary withdrawal and lack of efficacy (Figure S1).

Efficacy: Clinic Trough DBP and SBP

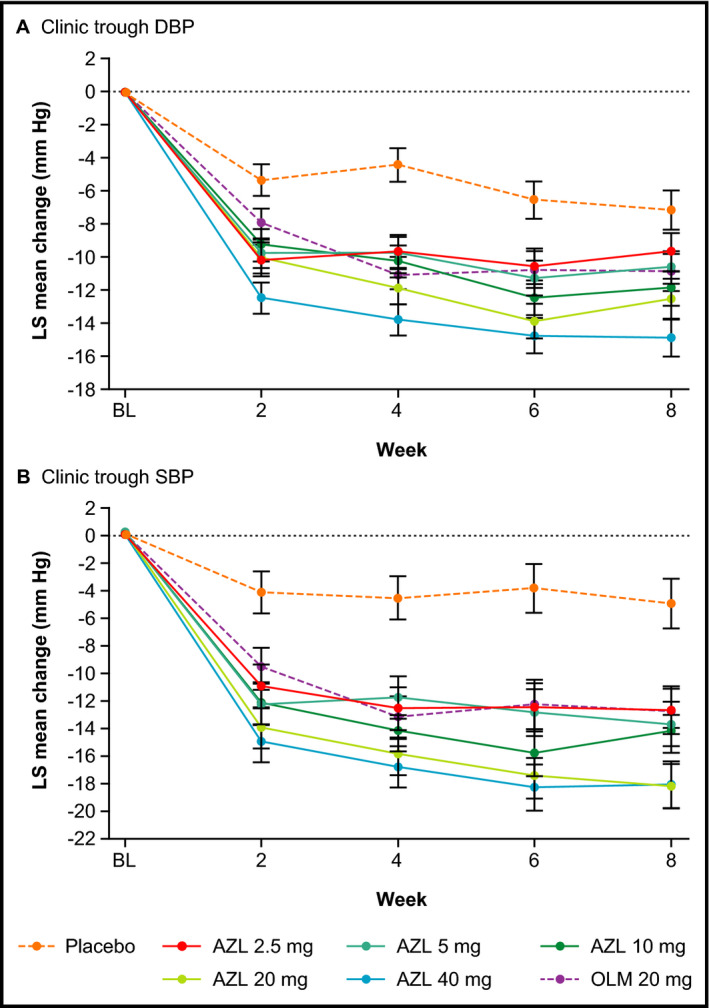

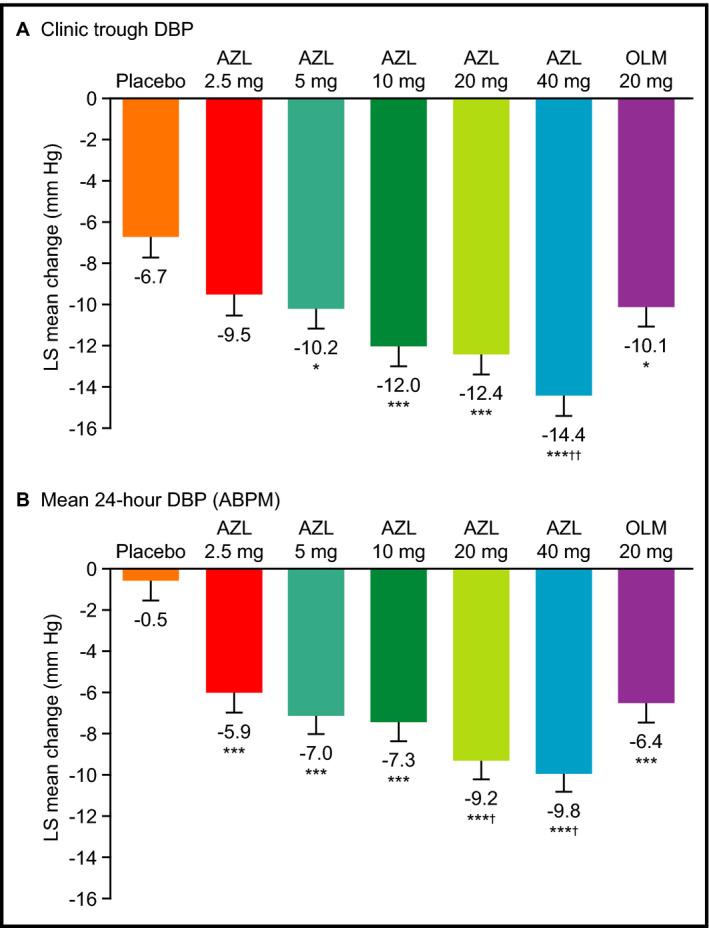

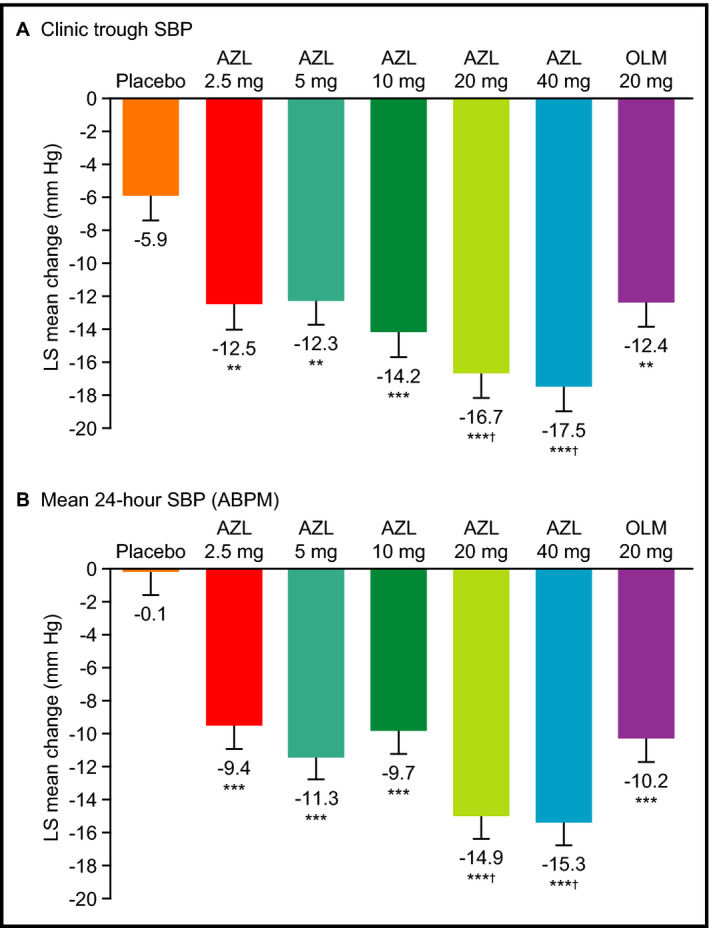

Statistically significant reductions in sitting clinic trough DBP and SBP relative to placebo occurred by week 2 (the earliest postbaseline visit) in all AZL treatment groups (Figure 1). At doses of 5, 10, 20, and 40 mg, AZL provided statistically significant reductions in sitting clinic DBP relative to placebo from baseline to week 8 (the primary endpoint) (Figure 2A, Table 2). All doses of AZL (2.5–40 mg) provided statistically significant reductions in sitting clinic SBP relative to placebo from baseline to week 8 (Figure 3A, Table 2). The effects of AZL on DBP and SBP appeared to be dose‐dependent across the entire dose range, with the greatest treatment effect seen in the AZL 40 mg treatment group (Figures 2A and 3A). There was a large mean placebo effect on clinic DBP and SBP (approximately −6 mm Hg for both) (Figures 2A and 3A). The higher doses of AZL (40 mg for DBP; 20 and 40 mg for SBP) also provided statistically significant reductions in clinic DBP and SBP relative to the OLM 20 mg reference treatment group at week 8 (Figures 2A and 3A, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Changes from baseline in sitting clinic diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) over 8 weeks (observed cases). (A) Sitting clinic trough DBP. (B) Sitting clinic trough SBP. Data are expressed as least squares mean change±standard error (observed cases). All changes for azilsartan (AZL) and olmesartan medoxomil (OLM) are statistically significant (P<.05) vs placebo, except for AZL 2.5 mg at week 8.

Figure 2.

Changes from baseline in diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at week 8. (A) Sitting clinic trough DBP. (B) Mean 24‐hour DBP from ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). Data are expressed as least squares mean change±standard error at 8 weeks (last observation carried forward). *P<.05 vs placebo. ***P<.001 vs placebo. † P<.05 vs olmesartan medoxomil (OLM). †† P<.01 vs OLM.

Table 2.

Between‐Group Comparisons for Efficacy Variables (Intention to Treat)

| BP Variable | AZL 2.5 mg | AZL 5 mg | AZL 10 mg | AZL 20 mg | AZL 40 mg | OLM 20 mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic sitting | n=72 | n=79 | n=75 | n=75 | n=75 | n=79 |

| ΔDBP vs placebo | −2.8 (−5.6 to 0.1) | −3.5 (−6.3 to −0.8)a | −5.3 (−8.1 to −2.5)b | −5.7 (−8.5 to −2.9)b | −7.7 (−10.5 to −4.9)b | −3.4 (−6.2 to −0.6)a |

| ΔDBP vs OLM | 0.6 (−2.1 to 3.4) | −0.1 (−2.8 to 2.6) | −1.9 (−4.6 to 0.8) | −2.3 (−5.1 to 0.4) | −4.3 (−7.0 to −1.5)c | – |

| ΔSBP vs placebo | −6.6 (−10.9 to −2.2)c | −6.4 (−10.6 to −2.2)c | −8.3 (−12.6 to −4.0)b | −10.8 (−15.1 to −6.5)b | −11.6 (−15.9 to −7.3)b | −6.5 (−10.7 to −2.3)c |

| ΔSBP vs OLM | −0.1 (−4.3 to 4.2) | 0.1 (−4.0 to 4.2) | −1.8 (−6.0 to 2.4) | −4.3 (−8.5 to −0.1)a | −5.1 (−9.3 to −0.9)a | – |

| 0–24‐h ABPM | n=58 | n=65 | n=59 | n=65 | n=66 | n=61 |

| ΔDBP vs placebo | −5.5 (−8.2 to −2.8)b | −6.5 (−9.1 to −3.9)b | −6.9 (−9.5 to −4.2)b | −8.8 (−11.4 to −6.2)b | −9.3 (−11.9 to −6.7)b | −6.0 (−8.6 to −3.3)b |

| ΔDBP vs OLM | 0.5 (−2.2 to 3.2) | −0.5 (−3.1 to 2.0) | −0.9 (−3.6 to 1.7) | −2.8 (−5.4 to −0.2)a | −3.4 (−5.9 to −0.8)a | − |

| ΔSBP vs placebo | −9.4 (−13.4 to −5.3)b | −11.2 (−15.2 to −7.3)b | −9.6 (−13.7 to −5.6)b | −14.8 (−18.8 to −10.8)b | −15.2 (−19.2 to −11.3)b | −10.1 (−14.2 to −6.1)b |

| ΔSBP vs OLM | 0.8 (−3.3 to 4.8) | −1.1 (−5.0 to 2.8) | 0.5 (−3.5 to 4.6) | −4.7 (−8.6 to −0.7)a | −5.1 (−9.0 to −1.2)a | – |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; AZL, azilsartan; BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; OLM, olmesartan medoxomil; SBP, systolic blood pressure. All data are expressed as least squares mean (95% confidence interval) (mm Hg) at week 8 last observation carried forward (clinic measurements) or at the final visit (ABPM). a P<.05. b P<.001. c P<.01.

Figure 3.

Changes from baseline in systolic blood pressure (SBP) at week 8. (A) Sitting clinic trough SBP. (B) Mean 24‐hour SBP from ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). Data are expressed as least squares mean change±standard error at 8 weeks (last observation carried forward). **P<.01 vs placebo. ***P<.001 vs placebo. † P<.05 vs olmesartan medoxomil (OLM).

The results for clinic standing trough DBP and SBP were consistent with the sitting measurements. For DBP, LS mean changes with AZL at week 8 (LOCF) ranged from −8.7 mm Hg (5 mg) to −12.9 mg (40 mg) compared with −5.7 mm Hg for placebo and −9.7 mm Hg for OLM 20 mg. For SBP, LS mean changes with AZL week 8 (LOCF) ranged from −11.1 mm Hg (5 mg) to −17.9 mm Hg (20 mg) compared with −4.6 mm Hg for placebo and −11.3 mm Hg for OLM 20 mg. Statistical comparisons between groups provided similar findings to the sitting measurements, with the exception that a statistically significant reduction in standing DBP relative to placebo was also seen for the AZL 2.5 mg treatment group (Table 2).

Efficacy: 24‐Hour ABPM

The results for BP reductions based on 24‐hour ABPM measurements generally mirrored the clinical measurements, and the effects of AZL on mean 24‐hour DBP and SBP appeared to be dose‐dependent across the entire dose range (Figure 2B and 3B). Results for mean daytime while awake, mean nighttime while asleep, and trough (last 2 hours of the dosing interval) values based on ABPM were similar to the mean 24‐hour results (Table 3). Unlike the clinic measurements, where placebo was associated with mean DBP and SBP reductions of 6 to 7 mm Hg, the effect of placebo on DBP and SBP based on ABPM (either 24‐hour, daytime, nighttime, or trough) was negligible (±0.5 mm Hg).

Table 3.

Change From Baseline DBP and SBP as Measured by ABPM

| ABPM Variable | Placebo (n=59) | AZL 2.5 mg (n=58) | AZL 5 mg (n=65) | AZL 10 mg (n=59) | AZL 20 mg (n=65) | AZL 40 mg (n=66) | OLM 20 mg (n=61) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 24‐h DBP | −0.5±1.0 | −5.9±1.0a | −7.0±0.9a | −7.3±1.0a | −9.2±0.9a,b | −9.8±0.9a,b | −6.4±0.9a |

| Mean daytime DBP while awake | −0.1±1.0 | −6.1±1.0a | −6.7±1.0a | −7.5±1.0a | −9.2±1.0a,b | −10.4±0.9a,c | −6.5±1.0a |

| Mean nighttime DBP while asleep | −0.5±1.1 | −5.4±1.1d | −7.1±1.1a | −6.0±1.1d | −8.0±1.1a | −7.7±1.1a | −5.7±1.1d |

| Mean trough DBP | −0.5±1.3 | −6.7±1.3d | −6.8±1.2a | −8.4±1.3a | −7.2±1.2a | −9.9±1.2a,b | −5.5±1.3d |

| Mean 24‐h SBP | −0.1±1.5 | −9.4±1.5a | −11.3±1.4a | −9.7±1.5a | −14.9±1.4a,b | −15.3±1.4a,d | −10.2±1.4a |

| Mean daytime SBP while awake | 0.4±1.5 | −9.5±1.5a | −11.0±1.5a | −9.9±1.5a | −14.8±1.5a,b | −16.3±1.4a,c | −10.2±1.5a |

| Mean nighttime SBP while asleep | −0.3±1.6 | −8.8±1.6a | −11.6±1.5a | −8.5±1.6a | −13.6±1.5a | −11.5±1.5a | −9.4±1.6a |

| Mean trough SBP | −0.4±1.8 | −10.7±1.8a | −12.0±1.7a | −11.2±1.8a | −13.0±1.7a | −13.3±1.7a | −8.9±1.8a |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; AZL, azilsartan; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; OLM, olmesartan medoxomil; SBP, systolic blood pressure. All data are expressed as least squares mean±standard error (mm Hg) at week 8. a P<0.001 vs placebo. b P<0.05 vs OLM. c P<0.01 vs OLM. d P<0.01 vs placebo.

The reductions in both mean 24‐hour DBP and SBP (without correcting for placebo) were consistently smaller (by up to 5 mm Hg) across the dose range than those seen with clinic measurements (Figures 2 and 3). However, after correcting for placebo, reductions in both mean 24‐hour DBP and SBP were consistently larger (by up to 4 mm Hg) (Table 2). Other differences in the clinical measurements were that LS mean changes in 0 to 24 hours mean DBP at week 8 were also statistically significantly greater with AZL 2.5 mg vs placebo and with AZL 20 mg vs OLM 20 mg (Figure 2, Table 2).

Safety and Tolerability

A total of 198 of 555 patients (36%) experienced one or more AE during the study (Table 4). The overall incidence of AEs in the AZL treatment groups was not dose‐dependent or different from placebo or OLM (Table 3). Nasopharyngitis was the most common AE, reported by 2.5% (AZL 20 mg and 40 mg) to 10.4% (placebo) of patients across the different treatment groups. Other AEs occurring in >5% of patients in any treatment group were headache and upper respiratory infection. Fourteen patients (2.5%) discontinued the study because of AEs, which were not dose‐dependent: three placebo (n=1 with arm pain; n=1 with uncontrolled hypertension, cough, fatigue, dizziness, and headache; n=1 with asthenia) and AZL 5 mg (n=1 with increased BP; n=1 with pancreatitis; n=1 with angina and tachycardia); two OLM (n=1 with worsening hypertension; n=1 with abdominal pain and diarrhea), AZL 20 mg (n=1 with increased BP; n=1 with acute myocardial infarction), and AZL 40 mg (n=1 with a transient ischemic attack; n=1 with orthostatic hypotension); and one in each of the AZL 2.5 mg (asthenia) and 10 mg (symptomatic hypotension) treatment groups. Serious AEs were reported in eight patients: two in each of the AZL 5, 10, 20, and 40 mg treatment groups; none of the serious AEs were considered to be related to the study drug by the investigator. There were no clinically meaningful changes in laboratory parameters (including ALT, AST, hemoglobin, potassium, creatinine), physical examination, vital signs, or 12‐lead electrocardiography results in any of the treatment groups.

Table 4.

Overview of AEs (Safety Population)

| Event, Number of Patients (%) | Placebo (n=77) | AZL 2.5 mg (n=78) | AZL 5 mg (n=80) | AZL 10 mg (n=80) | AZL 20 mg (n=79) | AZL 40 mg (n=81) | OLM 20 mg (n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious AE | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 0 |

| Any AE | 32 (41.6) | 26 (33.3) | 34 (42.5) | 26 (32.5) | 26 (32.9) | 29 (35.8) | 25 (31.3) |

| Mild | 15 (19.5) | 17 (21.8) | 21 (26.3) | 16 (20.0) | 13 (16.5) | 20 (24.7) | 17 (21.3) |

| Moderate | 16 (20.8) | 5 (6.4) | 12 (15.0) | 8 (10.0) | 11 (13.9) | 6 (7.4) | 6 (7.5) |

| Severe | 1 (1.3) | 4 (5.1) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.5) |

| Leading to discontinuationa | 3 (3.9) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) |

| AE (preferred term) in ≥5% of patients in any group | |||||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 8 (10.4) | 3 (3.8) | 6 (7.5) | 6 (7.5) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.8) |

| Headache | 2 (2.6) | 3 (3.8) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.7) | 5 (6.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (1.3) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6.3) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.5) | 0 |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; AZL, azilsartan; OLM, olmesartan medoxomil. aTemporary drug interruption or permanent discontinuation.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that AZL once daily at all doses tested up to 40 mg (with the exception of 2.5 mg for clinic DBP) provided rapid significant reductions in DBP and SBP (based on both clinic trough and 24‐hour ABPM measurements) relative to placebo in patients with mild to moderate uncomplicated essential hypertension. Changes in DBP and SBP with AZL 20 mg and 40 mg were statistically superior to those provided by OLM 20 mg (with the exception of 20 mg for clinic DBP).

It should be noted that this phase 2 dose‐ranging study involved an AZL tablet formulation, which differs from the commercially approved formulation in the United States and Europe, which is an AZL‐M prodrug tablet. The absolute bioavailability and mg:mg dose of the AZL tablet formulation is approximately equivalent to half that of the commercial AZL‐M tablet.3, 4, 5 The tablet formulation of AZL has been developed commercially in Japan and in a head‐to‐head phase 3 study in Japanese patients with hypertension, AZL 40 mg once daily provided statistically superior reduction in DBP and SBP compared with candesartan cilexetil 12 mg once daily (the maximum approved dose in Japan).11

The AZL 40 mg dose tablet (equivalent to 80 mg with the AZL‐M tablet formulation) provided an efficacy advantage over OLM 20 mg in the current study. Likewise, the phase 3 studies of AZL‐M 80 mg confirmed superior BP‐lowering efficacy over the maximum approved doses of OLM 40 mg or valsartan 320 mg (the maximum approved doses in the United States) and AZL‐M 80 mg became the recommended dose in the United States.4, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13 In a meta‐analysis of trials with ARBs (prior to the availability of AZL‐M) that used mean 24‐hour ABPM, OLM appeared to provide the largest SBP and DBP reductions among all of the ARBs (based on either ABPM or clinic measures).14 Thus, AZL‐M would appear to be among the most effective BP‐lowering drugs in the ARB class.

The range of doses selected for this study was determined to be safe and well tolerated in previous phase 1 and 2 clinical studies and this was also the case in the current study. The safety profile of AZL observed was similar to placebo and the comparator ARB OLM 20 mg. The overall incidence of AEs was not dose‐dependent and all doses were well tolerated. Serious AEs were distributed across the AZL treatment groups and were not considered related to study drug. The safety profile is consistent with previous data for other ARBs and was confirmed in subsequent phase 3 studies.8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17

The ABPM baseline data (representing a mean over 24 hours) were more uniform than those of clinic BP (an average of three measurements taken consecutively in the morning). As expected from previous studies with BP‐lowering drugs, the effects on DBP and SBP measured using 24‐hour ABPM were several mm Hg smaller than effects based on clinic measurements (by up to 5 mm Hg), probably as a result of the absence of a white‐coat effect. However, what was surprising in the current study was that, after correcting for placebo, reductions based on ABPM appeared to be consistently greater than clinic measures (by up to 4 mm Hg, although no statistical comparisons were performed). Similar findings were reported in a placebo‐controlled study of the investigational antihypertensive agent darusentan, where the drug provided a significant improvement in BP vs placebo based on 24‐hour ABPM, but not based on clinic measurements (the primary outcome).18 In that study, an unexplained large clinic placebo response late in the trial appears to have influenced the results. This reinforces the importance of including 24‐hour ABPM measures as primary endpoints in clinical trials of BP‐lowering drugs (as employed in the AZL‐M phase 3 trials), as it avoids any confounding from a large placebo effect, in addition to other factors. Even though there was a large placebo response in the current study, it was relatively consistent at all time points and there was no late effect. Consequently, the current study did not have any divergent conclusions from the two BP methods (except for some minor differences in statistical significance at lower doses).

Conclusions

The results of this study show that AZL has potent antihypertensive effects and a good tolerability profile in patients with mild to moderate uncomplicated essential hypertension. Treatment with AZL at doses ranging from 5 to 40 mg (and 2.5 mg based on secondary ABPM endpoints) resulted in significant, rapid reductions in clinic DBP and SBP. Furthermore, AZL 40 mg (and 20 mg for secondary ABPM endpoints) was more effective than OLM 20 mg. Along with the other phase 2 dose‐range study using the AZL‐M capsule formulation, these findings provided the basis for subsequent phase 3 trials using the commercial AZL‐M tablet in the dose range of 20 to 80 mg/d and employing mean 24‐hour ABPM.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Patient disposition. AZL indicates azilsartan; OLM, olmesartan. The reasons for permanent discontinuation from the study are listed.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

AP is retired but was an employee of Takeda, the company that sponsored the study, during the time the research was conducted. CC is a full‐time employee of Takeda. Medical writing assistance was provided by Absolute Healthcare Communications Ltd, Twickenham, United Kingdom, and was funded by Takeda.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:82–89. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12873. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Kurtz TW, Kajiya T. Differential pharmacology and benefit/risk of azilsartan compared to other sartans. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2012;8:133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michel MC, Foster C, Brunner HR, Liu L. A systematic comparison of the properties of clinically used angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonists. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:809–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research . Azilsartan medoxomil (Edarbi) NDA 200‐796 Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review. Feb 2011. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2011/200796Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf. Accessed 19 August #bib2014.

- 4. Edarbi (azilsartan medoxomil) tablets. U.S. prescribing information. Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Atlanta, GA, USA. Jul 2014. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/200796s006lbl.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- 5. Edarbi (azilsartan medoxomil) tablets. Summary of product characteristics. Takeda Pharma A/S, Taastrup, Denmark. Jul 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_Product_Information/human/002293/WC500119204.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- 6. O'Brien E. Twenty‐four‐hour ambulatory blood pressure measurement in clinical practice and research: a critical review of a technique in need of implementation. J Intern Med. 2011;269:478–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schmieder RE, Ruilope LM, Ott C, et al. Interpreting treatment‐induced blood pressure reductions measured by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bakris GL, Sica D, Weber M, et al. The comparative effects of azilsartan medoxomil and olmesartan on ambulatory and clinic blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sica D, White WB, Weber MA, et al. Comparison of the novel angiotensin II receptor blocker azilsartan medoxomil vs valsartan by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White WB, Weber MA, Sica D, et al. Effects of the angiotensin receptor blocker azilsartan medoxomil versus olmesartan and valsartan on ambulatory and clinic blood pressure in patients with stages 1 and 2 hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rakugi H, Enya K, Sugiura K, Ikeda Y. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of azilsartan with that of candesartan cilexetil in Japanese patients with grade I‐II essential hypertension: a randomized, double‐blind clinical study. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benicar (olmesartan medoxomil) tablets. U.S. prescribing information. Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA. Sep 2014. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/021286s032lbl.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- 13. Diovan (valsartan) tablets. U.S. prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., East Hanover, NJ, USA. Sep 2014. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/021283s041s044lbl.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- 14. Fabia MJ, Abdilla N, Oltra R, et al. Antihypertensive activity of angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists: a systematic review of studies with 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1327–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mazzolai L, Burnier M. Comparative safety and tolerability of angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Drug Saf. 1999;21:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taylor AA, Siragy H, Nesbitt S. Angiotensin receptor blockers: pharmacology, efficacy, and safety. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siragy HM. A current evaluation of the safety of angiotensin receptor blockers and direct renin inhibitors. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:297–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bakris GL, Lindholm LH, Black HR, et al. Divergent results using clinic and ambulatory blood pressures: report of a darusentan‐resistant hypertension trial. Hypertension. 2010;56:824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Patient disposition. AZL indicates azilsartan; OLM, olmesartan. The reasons for permanent discontinuation from the study are listed.