Abstract

The effect of lowering sympathetic nerve activity by renal denervation (RDN) is highly variable. With the exception of office systolic blood pressure (BP), predictors of the BP‐lowering effect have not been identified. Because dietary sodium intake influences sympathetic drive, and, conversely, sympathetic activity influences salt sensitivity in hypertension, we investigated 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion in participants of the SYMPATHY trial. SYMPATHY investigated RDN in patients with resistant hypertension. Both 24‐hour ambulatory and office BP measurements were end points. No relationship was found for baseline sodium excretion and change in BP 6 months after RDN in multivariable‐adjusted regression analysis. Change in the salt intake–measured BP relationships at 6 months vs baseline was used as a measure for salt sensitivity. BP was 8 mm Hg lower with similar salt intake after RDN, suggesting a decrease in salt sensitivity. However, the change was similar in the control group, and thus not attributable to RDN.

Keywords: dietary sodium, hypertension, renal denervation, salt sensitivity, sodium intake

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the introduction of percutaneous renal denervation (RDN) for treatment of so‐called resistant hypertension in 2009, the appreciation of the technique has changed from worldwide enthusiasm to widespread disappointment. Several studies and systemic reviews1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 have adjusted the expectations from the solution to hypertension in general to a possibly useful addition in antihypertensive treatment after further improvement of the procedure.7 Patient selection has been one of the explanations for the large variability in the blood pressure (BP) effect, because the contribution of sympathetic hyperactivity to hypertension may differ significantly between patients.8, 9

Dietary sodium intake is known to be related to sympathetic activity, with lower intake associated with higher sympathetic drive.10 Conversely, since efferent sympathetic activity directly increases tubular sodium absorption,11 lowering sympathetic output to the kidneys may be beneficial especially in patients with high salt intake as an important contributor to their hypertension. RDN, aimed at lowering sympathetic hyperactivity, might improve salt sensitivity.12 Our hypothesis was that dietary salt intake is related to the BP‐lowering effect of RDN. Measurement of salt excretion would then be helpful to select patients likely to benefit from the procedure. We therefore set out to investigate the relationship of dietary salt intake with the BP‐lowering effect of RDN and change in salt sensitivity after RDN.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

SYMPATHY is a multicenter randomized controlled trial conducted in the Netherlands from 2013 to 2016. The design and rationale of the study were previously published.13 In short, participants were eligible for inclusion if they had resistant hypertension, defined as an average daytime systolic BP ≥135 mm Hg despite use of three or more BP‐lowering drugs, or with use of fewer antihypertensive drugs as a result of intolerance to at least two of the major antihypertensive drug classes. Major exclusion criteria were severe renal insufficiency (estimated glomerular filtration rate <20 mL/min per 1.73 m2) and renal artery anatomy ineligible for treatment. A standardized protocol was provided to exclude secondary and white‐coat hypertension before inclusion. Adherence to antihypertensive drug treatment and dietary sodium restriction were discussed as part of usual care before inclusion. No dietary manipulations were performed in SYMPATHY. Randomization was in a 2:1 ratio to RDN added to the usual antihypertensive drug regimen vs usual antihypertensive drug therapy alone. The antihypertensive medication was to remain stable during follow‐up unless clinical reasons (eg, symptomatic hypotension or cardiovascular events) made adjustments necessary. The primary end point was assessed at 6 months. Patients and physicians were blinded to the primary outcome of daytime systolic BP. The ethical review committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht approved the protocol and all participants gave signed informed consent.

2.2. Measurements

After 3 months of stable antihypertensive drug treatment, patients could be included in the study and a baseline visit was planned. At baseline, 24‐hour ambulatory BP measurement was performed. BP was measured every 30 minutes during the day and every 60 minutes during the night. The measurement was considered to be valid when ≥70% of the recordings had been successful. Office BP was measured using an automated device with the patient in the sitting position after 10 minutes of rest, twice in both arms. The mean value was taken as office BP. Blood was drawn after an overnight fast in the morning following the ambulatory BP measurement. Participants provided a 24‐hour urine sample collected the day before the baseline visit. Detailed written instructions were provided to increase completeness of the collection. Sodium, potassium, creatinine, and protein excretion were measured in the urine. At 6 months after the baseline visit, both ambulatory BP and office BP were measured again, and blood and 24‐hour urine samples collected. At both time points, 24‐hour urine collection and BP measurements were thus performed simultaneously. Because antihypertensive medication had to be stable 3 months before the baseline visit and was to remain stable during the study (unless change was necessary for clinical reasons as described in the protocol), participants could be concluded to be in a steady state, with 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion representing dietary sodium intake and adherence to the salt restriction advice. The patients' weight was measured at both time points without shoes in light clothing. Height was measured without shoes at baseline. Participants were asked to bring all medication used to the visits. Frequency and dose of antihypertensive drugs used were recorded and checked with the patient. Combination preparations were recorded as their separate components. To include data on number of antihypertensive drugs used and dosage, defined daily dosages were calculated for classes of antihypertensive drugs. The defined daily dosage methodology was developed by the World Health Organization to facilitate use of drug consumption data in studies. Drugs with an Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code were assigned a defined daily dosage (DDD), a unit of measurement defined as the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication.14 For this study, defined daily dosages of antihypertensive drugs from different classes were added to a total number of antihypertensive defined daily dosages used.

2.3. Intervention

Usual care was based on the guidelines of the European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology.15 In the intervention group, RDN was performed by an interventional radiologist or cardiologist according to the manufacturers' instructions, within 1 month after the baseline visit. The Symplicity Flex Catheter (Medtronic) was used in the majority of patients. After conditional reimbursement was expanded to the EnligHTN Catheter (St. Jude Medical), this catheter could be used in the study as well.

2.4. Urine sample analyses

For the first part of this study, the relationship of dietary sodium intake with the BP‐lowering effect of RDN, interest was in the intervention group only in which RDN had to be performed within 1 month after the baseline visit (crossover was allowed for patients in the control group after 6 months). Patients randomized to RDN who did not have the procedure were excluded (per protocol analysis). Subsequently, participants who did not provide a baseline 24‐hour urine sample were excluded. The accuracy of collection of the 24‐hour urine sample was determined based on the amount of creatinine in the sample. Urinary creatinine excretion in 24 hours depends on muscle mass when in a steady state. Formulas to estimate 24‐hour creatinine excretion from sex, age, and weight, representing the main determinants of muscle mass, have been developed in several populations.16 Expected creatinine excretion based on sex, age, and weight was calculated and compared with the measured value. For this study, the formula proposed by Forni and Ogna was used.17 This formula was developed and validated in a Swiss study of adult participants with preserved kidney function and of white race, representative of the general European population. Because creatinine excretion is normally distributed in the population, the range between the 5th and 95th percentile can also be determined as described by these authors (similar to growth charts, an individual can have a low or high creatinine excretion for his/her age, sex, and weight). The measured creatinine excretion is then compared with the estimated value. A large difference between the two raises suspicion of inadequate collection of the 24‐hour urine sample. In this study, a 24‐hour urine sample was considered valid when measured creatinine excretion was between the 5th and 95th percentiles of the estimated creatinine excretion. Measured sodium excretion in 24 hours was then used in the analysis. In an additional analysis, performed to be able to use all urine samples regardless of the accuracy of collection, sodium/creatinine ratios from the samples were used to estimate 24‐hour sodium excretion using the formula developed by Tanaka for spot urine samples.18 Both formulas can be found in the Appendix S1.

2.5. Salt sensitivity assessment

Because no dietary manipulations were performed in SYMPATHY, salt sensitivity could not be investigated with the standard method of changing sodium intake with comparison of BP at low vs high salt diets. As a proxy, the relationship of sodium excretion (assumed to equal sodium intake since participants were stably on their regular diet) with systolic BP measured in the same 24 hours was compared at baseline and at 6 months after RDN. Initial analysis again was on a selection of urine samples deemed to have been well collected, based on the measured creatinine excretion between p5‐p95 of the estimated value criterion described above, both at baseline and at 6 months. Moreover, samples were excluded if 24‐hour creatinine excretion was more than 30% different at 6 months compared with baseline (representing remaining suspicion of major collection errors). As for the primary analysis, an additional analysis was performed using estimated 24‐hour sodium excretion based on the Tanaka formula for spot urine samples. Change in salt sensitivity during follow‐up was analyzed by the same method in the control group, representative of change not attributable to the RDN procedure.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are described as mean with standard deviation or proportions as appropriate. Change in 24‐hour systolic BP and office systolic BP between baseline and 6 months after RDN was investigated using a paired samples t test. Multivariable‐adjusted linear regression analyses were used to investigate a relationship of baseline dietary sodium intake (represented by 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion) with the change in BP 6 months after RDN (primary analysis). First, urine samples suggestive of inaccurate collection were excluded. Hereafter, the regression analysis was repeated using estimated 24‐hour sodium excretion based on the Tanaka formula, including all samples. Antihypertensive drug use, measured as total amount of defined daily dosages used, was adjusted for in the last model. In the second part of the study, linear regression was used with urinary sodium excretion as the independent and measured systolic BP as the dependent variable, both at baseline and at 6 months. In these analyses, antihypertensive drug use was adjusted for because several of these drugs potentially influence salt sensitivity (again using defined daily dosages). These analyses were repeated in the control group, to determine whether a change in salt sensitivity during follow‐up was caused by the RDN procedure or by other factors. SPSS version 21 (IBM) was used for all analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population and change in BP after RDN

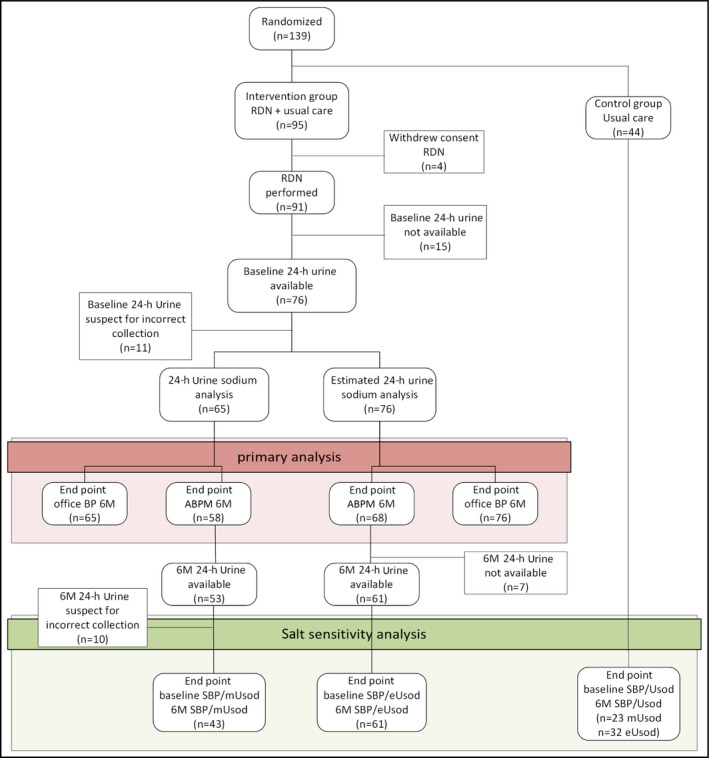

Of 95 participants randomized to RDN, four decided against receiving RDN and were excluded. Baseline and follow‐up BP and baseline 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion were available for 76 participants. Figure 1 shows the number of participants in the different analyses and reasons for exclusion. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 and antihypertensive drug use in Table 2. Mean dietary sodium intake was 154 ± 65 mmol/d and mean 24‐hour BP 159 ± 15/90 ± 14 mm Hg. One third of the participants had diabetes mellitus, almost half had a history of cardiovascular disease, and kidney function was well preserved (mean estimated glomerular filtration rate 78 ± 18 mL/min per 1.73 m2). Five urine samples were excluded for incomplete collection (below the p5) and six for overcollection (ending the collection period too late, measured creatinine excretion above the p95). Six months after RDN, 24‐hour systolic BP had decreased by 7.5 mm Hg (standard error [SE] 2.7 mm Hg, P = .007) and 24‐hour diastolic BP by 4.5 mm Hg (SE 1.6 mm Hg, P = .007). The change in office BP was –8.1 mm Hg (SE 2.8, P = .005) for systolic BP and –4.1 mm Hg (SE 1.7, P = .014) for diastolic BP. Mean sodium intake was only marginally lower at 6 months (mean difference 16 mmol/d, SE 9; P = .08).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study. ABPM indicates ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP, blood pressure; eUsod, estimated urinary sodium excretion; mUsod, measured urinary sodium excretion; RDN, renal denervation; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | ||

| Men, % | 53 | |

| Age at renal denervation, y | 62 | 12 |

| White race, % | 96 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 33 | |

| History of cardiovascular disease, % | 47 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.5 | 5.0 |

| Current smoking, % | 21 | |

| Alcohol intake ≥1 unit/d, % | 65 | |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 78 | 18 |

| Urinary sodium excretion, mmol/d | 154 | 65 |

| Estimated sodium excretion, mmol/d | 167 | 30 |

| 24‐h mean systolic BP, mm Hg | 159 | 15 |

| 24‐h mean diastolic BP, mm Hg | 90 | 14 |

| 24‐h mean daytime systolic BP, mm Hg | 162 | 16 |

| 24‐h mean daytime diastolic BP, mm Hg | 92 | 14 |

| Office systolic pressure, mm Hg | 170 | 25 |

| Office diastolic pressure, mm Hg | 94 | 16 |

| Office pulse pressure, mm Hg | 76 | 19 |

| Change in mean 24‐h systolic BP at 6 mo, mm Hg | −7.5 | −12.9 to −2.1 |

| Change in mean 24‐h diastolic BP at 6 mo, mm Hg | −4.5 | −7.7 to −1.3 |

| Change in office systolic BP at 6 mo, mm Hg | −8.1 | −13.7 to −2.5 |

| Change in office diastolic BP at 6 mo, mm Hg | −4.1 | −7.4 to −0.9 |

Data are expressed as proportions, mean with standard deviation, or difference with 95% confidence intervals as appropriate. Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Table 2.

Antihypertensive drug use at baseline

| α‐Blocker | 28.0 |

| ACEi | 25.3 |

| ARB | 64.0 |

| Renin inhibitor | 4.0 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 32.0 |

| β‐Blocker | 69.3 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 68.0 |

| Diuretic | 78.7 |

| Centrally acting sympatholytic agent | 5.3 |

| Direct‐acting vasodilator | 5.3 |

| No. of antihypertensive drugs | 3.8 ± 1.4 |

| Total defined daily dosage use | 5.6 ± 4.3 |

Values are expressed as proportions for different drug classes, mean with standard deviation for antihypertensive drugs, and for defined daily dosages per participant. Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

3.2. Dietary sodium intake and BP after RDN

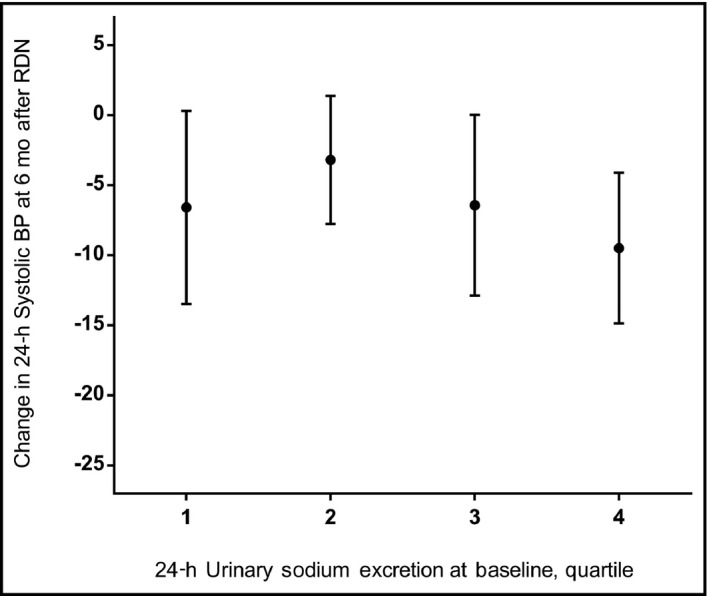

Dietary sodium intake at baseline was not related to the change in BP after RDN in the different models (Table 3, A). Analyses were performed for every 10‐mmol increase in sodium excretion per day (comparable with 0.58 g dietary salt [sodium chloride] intake) and for quartiles of sodium intake, and adjusted for baseline systolic BP, age, sex, body mass index, race, kidney function, and antihypertensive drug use. Neither change in 24‐hour systolic BP nor change in office systolic BP were related to dietary sodium intake. For example, in the model adjusted for age, sex, and baseline systolic BP, 10‐mmol higher sodium excretion at baseline was related to a 0.5‐mm Hg greater decline (−0.5 mm Hg) in ambulatory systolic BP at 6 months, with a 95% confidence interval of −1.5 to +0.5 mm Hg. The change in BP according to quartile of sodium intake is shown in Figure 2. Table 3, B shows that results were similar in the analyses using the estimated sodium excretion with no significant relationship found for baseline sodium excretion with change in BP at 6 months after RDN.

Table 3.

Baseline salt excretion and change in BP at 6 mo for measured (A) and estimated (B) 24‐h urinary sodium excretion

| Change in 6‐mo office systolic BP | Change in 6‐mo 24‐h ambulatory systolic BP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | P value | B | 95% CI | P value | |||

| (A) | ||||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Baseline urinary sodium, 10 mmol/24u | −0.20 | −1.11 | 0.71 | .67 | −0.56 | −1.58 | 0.47 | .28 |

| Baseline sodium excretion quartile | −0.75 | −5.83 | 4.34 | .77 | −0.83 | −6.52 | 4.86 | .77 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Baseline urinary sodium, 10 mmol/24u | −0.43 | −1.28 | 0.41 | .31 | −0.50 | −1.54 | 0.54 | .34 |

| Baseline sodium excretion quartile | −1.46 | −6.16 | 3.23 | .54 | −0.68 | −6.40 | 5.04 | .81 |

| Model 3 | ||||||||

| Baseline urinary sodium, 10 mmol/24u | −0.53 | −1.55 | 0.48 | .30 | −0.20 | −1.43 | 1.03 | .75 |

| Baseline sodium excretion quartile | −1.85 | −7.23 | 3.52 | .49 | 1.17 | −5.24 | 7.59 | .72 |

| Model 4 | ||||||||

| Baseline urinary sodium, 10 mmol/24u | −0.53 | −1.55 | 0.49 | .30 | −0.20 | −1.44 | 1.04 | .75 |

| Baseline sodium excretion quartile | −1.85 | −7.26 | 3.57 | .50 | 1.17 | −5.30 | 7.65 | .72 |

| Model 5 | ||||||||

| Baseline urinary sodium, 10 mmol/24u | −0.58 | −1.60 | 0.45 | .26 | −0.33 | −1.60 | 0.94 | .60 |

| Baseline sodium excretion quartile | −2.36 | −7.86 | 3.14 | .39 | 0.32 | −6.47 | 7.11 | .93 |

| Model 6 | ||||||||

| Baseline urinary sodium, 10 mmol/24u | −0.60 | −1.64 | 0.45 | .26 | −0.39 | −1.70 | 0.91 | .55 |

| Baseline sodium excretion quartile | −2.35 | −7.92 | 3.21 | .40 | 0.20 | −6.70 | 7.09 | .95 |

| Model 7 | ||||||||

| Baseline urinary sodium, 10 mmol/24u | −0.59 | −1.65 | 0.46 | .26 | −0.39 | −1.69 | 0.92 | .55 |

| Baseline sodium excretion quartile | −2.64 | −8.12 | 2.84 | .34 | 0.13 | −6.53 | 6.80 | .97 |

| (B) | ||||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Estimated 24‐h sodium excretion, 10 mmol/24 h | −0.25 | −2.15 | 1.64 | .79 | −0.004 | −1.80 | 1.79 | 1.00 |

| Estimated sodium excretion quartile | −1.90 | −6.90 | 3.09 | .45 | 1.21 | −3.68 | 6.10 | .62 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Estimated 24‐h sodium excretion, 10 mmol/24 h | −0.80 | −2.57 | 0.97 | .37 | 0.13 | −1.70 | 1.97 | .89 |

| Estimated sodium excretion quartile | −3.02 | −7.65 | 1.62 | .20 | 1.61 | −3.38 | 6.60 | .52 |

| Model 3 | ||||||||

| Estimated 24‐h sodium excretion, 10 mmol/24 h | −0.67 | −2.48 | 1.15 | .46 | 0.42 | −1.46 | 2.29 | .66 |

| Estimated sodium excretion quartile | −2.71 | −7.37 | 1.96 | .25 | 2.08 | −2.94 | 7.09 | .41 |

| Model 4 | ||||||||

| Estimated 24‐h sodium excretion, 10 mmol/24 h | −0.67 | −2.50 | 1.16 | .47 | 0.42 | −1.47 | 2.31 | .66 |

| Estimated sodium excretion quartile | −2.73 | −7.45 | 2.00 | .25 | 2.05 | −3.03 | 7.12 | .42 |

| Model 5 | ||||||||

| Estimated 24‐h sodium excretion, 10 mmol/24 h | −0.82 | −2.70 | 1.06 | .39 | 0.11 | −1.86 | 2.09 | .91 |

| Estimated sodium excretion quartile | −3.18 | −8.03 | 1.67 | .20 | 1.19 | −4.24 | 6.61 | .66 |

| Model 6 | ||||||||

| Estimated 24‐h sodium excretion, 10 mmol/24 h | −0.83 | −2.73 | 1.06 | .38 | 0.05 | −1.97 | 2.06 | .96 |

| Estimated sodium excretion quartile | −3.19 | −8.07 | 1.70 | .20 | 1.07 | −4.43 | 6.57 | .70 |

| Model 7 | ||||||||

| Estimated 24‐h sodium excretion, 10 mmol/24 h | −0.61 | −2.57 | 1.35 | .54 | 0.04 | −2.05 | 2.12 | .97 |

| Estimated sodium excretion quartile | −2.71 | −7.74 | 2.32 | .29 | 0.88 | −4.75 | 6.52 | .75 |

Estimation of 24‐h sodium excretion was based on the Tanaka formula for spot urines.

Model 1: crude.

Model 2: adjusted for baseline systolic blood pressure (BP).

Model 3: adjusted for baseline systolic BP, age, and sex.

Model 4: adjusted for baseline systolic BP, age, sex, and race.

Model 5: adjusted for baseline systolic BP, age, sex, race, and body mass index (BMI).

Model 6: adjusted for baseline systolic BP, age, sex, race, BMI, and baseline estimated glomerular filtration ratio (eGFR).

Model 7: adjusted for baseline systolic BP, age, sex, race, BMI, baseline eGFR, and baseline antihypertensive drug use.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Baseline sodium excretion and change in blood pressure (BP) after renal denervation. Mean change with whiskers indicating standard errors. Quartiles of sodium excretion: 1 = ≤107 mmol/d, 2 = 108‐145 mmol/d, 3 = 146‐193 mmol/d, and 4 = ≥194 mmol/d.

3.3. Changes in salt sensitivity

Daily sodium excretion was not related to ambulatory systolic BP either at baseline or at 6 months after RDN (Figures S1 and S2). The crude regression analysis showed a decrease of 0.06 mm Hg in 24‐hour systolic BP for every 10‐mmol higher sodium intake (95% confidence interval, −0.98 to +0.85) at baseline and of 0.06 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, −1.08 to +0.95) at 6 months after RDN. The intercept of the regression line was 8 mm Hg lower at 6 months (149 mm Hg vs 157 mm Hg at baseline) representing a shift of the sodium intake–BP relationship to a lower level after RDN. Thus, at a given level of sodium intake, BP was lower after RDN, indicating a decrease in salt sensitivity. Adjustment for antihypertensive drug use did not change the results. The analysis using the estimation of sodium excretion by the Tanaka formula showed a similar result, with a decrease in the intercept of 13 mm Hg (164 vs 177 mm Hg at baseline). In the control group, however, a similar shift of the sodium intake–BP relationship was found to an even lower level (‐19 mm Hg) at 6 months, both in the patients with well‐collected urine samples (n = 23) and in the estimated sodium excretion analyses (n = 32). Thus, although salt sensitivity decreased during follow‐up, the decrease was caused by other factors than the RDN procedure.

4. DISCUSSION

Dietary sodium intake was not related to the BP‐lowering effect of RDN in this study. Salt sensitivity decreased after RDN, but a similar decrease was found in the control group during follow‐up.

4.1. Dietary sodium intake and BP after RDN

Dietary sodium restriction is routinely advised in hypertension and leads to an important lowering of BP also in so‐called resistant hypertension.19, 20, 21 Sympathetic activity, however, increases when sodium intake is decreased, similar to the effect of (thiazide) diuretics and representing a feedback mechanism.10, 22, 23 Efferent sympathetic activity to the kidneys directly stimulates tubular sodium reabsorption, aside from stimulating renin secretion and decreasing renal blood flow.11 Measurement of sodium excretion, representing dietary sodium intake, was therefore hypothesized to be useful to predict the BP‐lowering effect of RDN. No such relationship was found in the current study. One explanation could be that both a low and high sodium intake are related to a beneficial effect of RDN. Since the participants in this study with low sodium intake were still severely hypertensive, the contribution of both the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system and sympathetic hyperactivity to the hypertension is assumed to have been high in these patients. RDN is expected to lower both as these systems are highly connected.24 In participants on a high sodium diet, volume expansion can be hypothesized to be important in the pathophysiology of hypertension, and RDN leading to increased sodium excretion expected to lead to a decrease in BP. The relationship of sodium intake and the BP‐lowering effect of RDN has been scarcely studied. In studies investigating clinical factors predictive of the BP response after RDN, sodium intake was seldom included as a possibility.25, 26 Pöss and colleagues27 investigated the relationship of 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion as estimated from morning urine samples by the Kawasaki formula with the BP change after RDN. As in this study, no prediction of the change in BP after RDN was found. Because the effectiveness of the RDN procedure probably differs between patients, future studies using improved catheter systems or procedures (eg, more distal ablation and intraprocedural assessment of the effect) might find different results. At this time, measurement of urinary sodium excretion cannot be used to select patients with (resistant) hypertension likely to benefit from RDN.

4.2. Changes in salt sensitivity

Large, worldwide population studies have shown an increase of BP with higher sodium intake, with a steeper increase at higher levels (>3 g/d).28 Salt sensitivity (ie, change in BP in response to change in salt intake), is normally distributed in the population, as opposed to present or absent in an individual.29, 30 Salt sensitivity is higher in patients with higher age and in the presence of hypertension.28, 31 In animal models of salt‐sensitive hypertension, development of hypertension on high salt diet is attenuated by RDN, leading to the hypothesis that sympathetic activity is an important contributor to the development of salt‐sensitive hypertension.12, 31 Increased sympathetic activity counteracts pressure natriuresis, and a higher BP is needed to excrete sodium when sympathetic nerve activity is high.12, 30, 32 In the GenSalt (Genetic Epidemiology Network of Salt Sensitivity) study,33 increased sympathetic reactivity, measured as an increase in BP in a cold pressor test, has been shown to be related to salt sensitivity in humans. From this background, an effect of lowering sympathetic activity by RDN on salt sensitivity is expected. In this study, a shift was indeed found in the sodium intake–BP relationship in the whole study population in accordance with such an effect. However, a similar shift was found in the control group. The decrease in salt sensitivity is therefore not attributable to the RDN procedure.

Salt sensitivity has not been previously investigated in RDN studies. Pöss and colleagues27 relate a higher 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion after RDN to a beneficial effect of RDN. Because the amount of sodium excreted in the urine depends on what is ingested in the diet (if in a steady state, as assumed in both studies), this cannot be seen as proof for an increase in salt excretion attributable to a beneficial effect of the RDN procedure. As mean BP decreased after RDN in their study, it does show that the increase in sodium intake did not lead to an increase in BP, as would be expected.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are that BP and sodium excretion were measured carefully by 24‐hour ambulatory BP measurement and collection of 24‐hour urine samples both at baseline and 6 months after RDN. Participants were closely followed in the setting of a randomized clinical trial. Appropriateness of collection of 24‐hour urine samples was assessed and antihypertensive drug use and several clinical factors could be adjusted for in the analyses. However, the study also has important limitations. The main analysis of the BP‐lowering effect of RDN in SYMPATHY was neutral, suggesting insufficient effectiveness of the RDN procedure at least in some of the participants.34 Size is another limitation, especially for the salt‐sensitivity analysis, partly attributable to exclusions for suspected 24‐hour urine collection errors. No dietary interventions were performed in this study, and salt sensitivity therefore could not be investigated in the appropriate manner. No measurements of activity of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system were available. We therefore could not investigate whether a combination of sodium intake and renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system activity would better predict the BP‐lowering effect of RDN. However, adjustment for antihypertensive drug use, including renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibition, did not change the results. Lastly, from the main analysis of the SYMPATHY trial we now know that nonadherence to antihypertensive drug treatment is prevalent in these patients. This could have introduced bias in the current study as well.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Dietary sodium intake was not related to change in BP after RDN. Salt sensitivity decreased during follow‐up, but the change was not attributable to the RDN procedure. Dietary sodium intake cannot be used to identify patients that benefit from RDN. Dietary intervention studies might provide different findings on an effect of RDN on salt sensitivity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ROLE OF THE FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTORS

The financial contributors participated in discussions regarding the design and conduct of the study. Monitoring of the study and maintenance of the trial were performed by a contract research organization, Julius Clinical (www.juliusclinical.com), independent of the financial contributors. Collection, management, and analysis of the data were performed independent of the financial contributors. The manuscript was prepared by the authors of this article. The sponsor was permitted to review the manuscript and suggest changes but the final approval of content was exclusively retained by the authors.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SYMPATHY investigators and committees—Albert Schweizer Hospital Dordrecht: O Elgersma, AJJ IJsselmuiden, PHM van der Valk, P Smak Gregoor, S Roodenburg. Amphia Hospital, Breda: M Meuwissen, W Dewilde, I Hunze, J den Hollander. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein: HH Vincent, B Rensing, WJ Bos, Ivan Weverwijk. Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven: PAL Tonino, BRG Brueren, CJAM Konings, H Hendrix‐van Gompel. Isala Clinics, Zwolle: JE Heeg, J Lambert, JJ Smit, A Elvan, A Berends, B de Jager. Hospital group Twente, Almelo: G Laverman, PAM de Vries, A van Balen, M Stoel. Martini Hospital, Groningen: R Steggerda, L Niamut, W Bossen, J Biermann, I Knot. Medical Center Alkmaar, Alkmaar: JOJ Peels, JB de Swart, G Kimman, W Bax, Y van der Meij, J Reekers. Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague: AJ Wardeh, JHM Groeneveld, C Dille. Medical Center Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden: MH Hemmelder, R Folkeringa, M Sietzema, C Wassenaar. Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem: K Parlevliet, W Aengevaeren, M Tjon, M Hovens, A van den Berg, H Monajemi. Scheper Hospital, Emmen: FGH van der Kleij, A Schramm, A Wiersum. University Hospital Maastricht, Maastricht: B Kroon, M de Haan, M Das, H Jongen, E Herben, R Rennenberg. University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht: PJ Blankestijn, ML Bots, MM Beeftink, E de Beus, B Dijker, GWJ Frederix, RL de Jager, E van Maarseveen, MF Sanders, W Spiering, IS Velikopolskaia, L Vendrig, WL Verloop, EE Vink, EPA Vonken, M Voskuil, GA de Wit. All centers are located in The Netherlands. Executive committee: PJ Blankestijn, ML Bots, E de Beus, RL de Jager, L Vendrig. Steering committee: PJ Blankestijn (chair), ML Bots (vice chair), RL de Jager, L Vendrig, E de Beus, B Dijker, JE Heeg, J Vincent, CB Roes, J Deinum. Data Safety Monitoring Board: AJ Rabelink (chair), J Lenders, R Eijkemans. Monitoring: Julius Clinical

de Beus E, de Jager RL, Beeftink MM, et al; On behalf of the SYMPATHY study group . Salt intake and blood pressure response to percutaneous renal denervation in resistant hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2017;19:1125–1133. 10.1111/jch.13085

Funding information

SYMPATHY is an investigator‐driven trial and received unrestricted grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, No. 837004006), the Dutch Kidney Foundation (Nierstichting Nederland, No. CPI12.02), and Medtronic Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O'Neill WW, et al; SYMPLICITY HTN‐3 Investigators. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393‐1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mathiassen ON, Vase H, Bech JN, et al. Renal denervation in treatment‐resistant essential hypertension. A randomized, SHAM‐controlled, double‐blinded 24‐h blood pressure‐based trial. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1639‐1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Azizi M, Sapoval M, Gosse P, et al. Optimum and stepped care standardised antihypertensive treatment with or without renal denervation for resistant hypertension (DENERHTN): a multicentre, open‐label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:1957‐1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosa J, Widimsky P, Tousek P, et al. Randomized comparison of renal denervation versus intensified pharmacotherapy including spironolactone in true‐resistant hypertension: six‐month results from the Prague‐15 study. Hypertension. 2015;65:407‐413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pancholy SB, Subash Shantha GP, Patel TM, Sobotka PA, Kandzari DE. Meta‐analysis of the effect of renal denervation on blood pressure and pulse pressure in patients with resistant systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:856‐861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fadl Elmula FE, Jin Y, Yang WY, et al; European Network Coordinating Research On Renal Denervation (ENCOReD) Consortium. Meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials of renal denervation in treatment‐resistant hypertension. Blood Press. 2015;24:263‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moss JG, Belli AM, Coca A, et al. Executive summary of the joint position paper on renal denervation of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2016;34:2303‐2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iliescu R, Lohmeier TE, Tudorancea I, Laffin L, Bakris GL. Renal denervation for the treatment of resistant hypertension: review and clinical perspective. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309:F583‐F594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Esler M. The sympathetic nervous system in hypertension: back to the future? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grassi G, Dell'Oro R, Seravalle G, Foglia G, Trevano FQ, Mancia G. Short‐ and long‐term neuroadrenergic effects of moderate dietary sodium restriction in essential hypertension. Circulation. 2002;106:1957‐1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dibona GF. Neural control of the kidney: past, present, and future. Hypertension. 2003;41(3 pt 2):621‐624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Strazzullo P, Barbato A, Vuotto P, Galletti F. Relationships between salt sensitivity of blood pressure and sympathetic nervous system activity: a short review of evidence. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2001;23:25‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vink EE, de Beus E, de Jager RL, et al. The effect of renal denervation added to standard pharmacologic treatment versus standard pharmacologic treatment alone in patients with resistant hypertension: Rationale and design of the SYMPATHY trial. Am Heart J. 2014;167:308‐314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology . ATC/DDD Index 2017. 2017. Ref Type: Internet Communication.

- 15. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281‐1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ix JH, Wassel CL, Stevens LA, et al. Equations to estimate creatinine excretion rate: the CKD epidemiology collaboration. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:184‐191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ogna VF, Ogna A, Vuistiner P, et al. New anthropometry‐based age‐ and sex‐specific reference values for urinary 24‐hour creatinine excretion based on the adult Swiss population. BMC Med 2015;13:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tanaka T, Okamura T, Miura K, et al. A simple method to estimate populational 24‐h urinary sodium and potassium excretion using a casual urine specimen. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:97‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pimenta E, Gaddam KK, Oparil S, et al. Effects of dietary sodium reduction on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension: results from a randomized trial. Hypertension. 2009;54:475‐481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gay HC, Rao SG, Vaccarino V, Ali MK. Effects of different dietary interventions on blood pressure: systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension. 2016;67:733‐739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Graudal NA, Hubeck‐Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grassi G, Cattaneo BM, Seravalle G, Lanfranchi A, Bolla G, Mancia G. Baroreflex impairment by low sodium diet in mild or moderate essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1997;29:802‐807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Menon DV, Arbique D, Wang Z, ms‐Huet B, Auchus RJ, Vongpatanasin W. Differential effects of chlorthalidone versus spironolactone on muscle sympathetic nerve activity in hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1361‐1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dibona GF. Peripheral and central interactions between the renin‐angiotensin system and the renal sympathetic nerves in control of renal function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:395‐406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kandzari DE, Bhatt DL, Brar S, et al. Predictors of blood pressure response in the SYMPLICITY HTN‐3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:219‐227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Persu A, Azizi M, Jin Y, et al. Hyperresponders vs nonresponder patients after renal denervation: do they differ? J Hypertens. 2014;32:2422‐2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pöss J, Ewen S, Schmieder RE, et al. Effects of renal sympathetic denervation on urinary sodium excretion in patients with resistant hypertension. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104:672‐678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mente A, O'Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, et al. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:601‐611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen J. Sodium sensitivity of blood pressure in Chinese populations. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:127‐134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hall JE. Renal dysfunction, rather than nonrenal vascular dysfunction, mediates salt‐induced hypertension. Circulation. 2016;133:894‐906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elijovich F, Weinberger MH, Anderson CA, et al. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2016;68:e7‐e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dibona GF, Esler M. Translational medicine: the antihypertensive effect of renal denervation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R245‐R253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen J, Gu D, Jaquish CE, et al. Association between blood pressure responses to the cold pressor test and dietary sodium intervention in a Chinese population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1740‐1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Jager RL, de Beus E, Beeftink MM, et al. Impact of medication adherence on the effect of renal denervation: the SYMPATHY trial. Hypertension. 2017;69:678‐684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials