Abstract

Data on masked hypertension (MH) and white‐coat hypertension (WCH) in African populations are needed to estimate the true prevalence of hypertension in these populations because they have the highest burden of the disease. We conducted the first systematic review and meta‐analysis that summarized available data on the prevalence of WCH and MH in Africa. We searched PubMed and Scopus to identify all the articles published on MH and WCH in populations living in Africa from inception to November 30, 2017. We reviewed each study for methodological quality. A random‐effects model was used to estimate the prevalence of WCH and MH across studies. Eleven studies were included, all having a low‐risk of bias. The prevalence of masked hypertension was 11% (95% CI: 4.7‐19.3; 10 studies) in a pooled sample of 7789 individuals. The prevalence of WCH was 14.8% (95% CI: 9.4‐21.1; 8 studies) in a pooled sample of 4451 individuals. There was no difference on the prevalence of WCH and MH between studies in which participants were recruited from the community and the hospital. The prevalence of MH was higher in urban areas compared to rural ones; there was no difference for WCH. WHC and MH seem to be frequent in African populations, suggesting the importance of out‐of‐clinic BP measurement in the diagnosis and management of patients with hypertension in Africa, especially in urban areas for MH.

Keywords: ambulatory blood pressure/home, blood pressure monitor, epidemiology, general, hypertension

1. INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is the leading contributor to global burden of disease, affecting about 1 billion adults and accounting for more than 9 million deaths annually and 9% of global disability adjusted life years.1, 2 The burden of hypertension has been continuously rising in African populations over the past decades, with this region having now the highest age‐standardized prevalence of the disease.2 In most of affected individuals in Africa, hypertension remains undiagnosed, untreated, or uncontrolled. Indeed, a recent review estimated that about 30% of adults in Africa have hypertension, with only 27% aware of their condition, 18% who are on treatment, and 7% who achieve controlled blood pressure (BP).3

Accurate diagnosis of hypertension is paramount for both epidemiological estimations and clinical management. Conventional BP measurement (CBPM) has been used to evaluate the burden of hypertension in most studies conducted in Africa. In almost all clinical settings, hypertension is defined based on clinic BP measurements alone. CBPM is limited by its inability to distinguish white coat hypertension (WCH) from sustained hypertension and to diagnose masked hypertension (MH). WCH is a condition where an individual presents as hypertensive in clinic, but is normotensive out of the clinic when BP is measured over 24‐hour using ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring (HBPM).4 In contrast, a patient with MH has normal BP in clinic, but abnormal BP pattern on ABPM or HBPM.5

The diagnosis of WCH and MH has important epidemiological, clinical, and economic implications. Patients with MH are underdiagnosed and therefore undertreated, presenting significant cardiovascular risk.5 On the other hand, individuals with WCH, which does not substantially increase the cardiovascular risk, may receive unnecessary life‐long treatment, resulting in economic losses.4 In African countries where hypertension is a major and growing public health problem, data on MH and WCH are needed to estimate the true burden of hypertension and ultimately inform policies for better diagnosis and treatment of hypertension and appropriate resource allocation. We present here a systematic review and meta‐analysis that summarized available data on the prevalence of WCH and MH in studies conducted in Africa.

2. METHODS

This review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.6

2.1. Literature search

We performed a search of PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus to identify all relevant articles published on MH and WCH in individuals residing in Africa from inception to November 30, 2017. No language restriction was applied. We conceived and applied a search strategy based on the combination of the names of each of the 54 African countries and African sub‐regions and terms relevant to MH and WCH, including “masked hypertension,” “white coat hypertension,” “reverse white coat effect,” “white‐coat normotension,” “isolated clinic normotension,” “isolated clinic hypertension,” “isolated office hypertension,” “isolated home hypertension,” “isolated ambulatory hypertension,” and “white coat effect.” We scanned the reference lists of all relevant reviews and all included studies to identify other potential eligible studies.

2.2. Selection of studies for inclusion in the review

We included cross‐sectional, cohort and case‐control studies reporting on the prevalence of MH and/or WCH in individuals residing in African countries. We excluded studies case series with a small sample size (less than 50 subjects) and studies lacking primary data and/or explicit description of methods. For studies published in more than one report (duplicates), the most comprehensive reporting the largest sample size was considered.

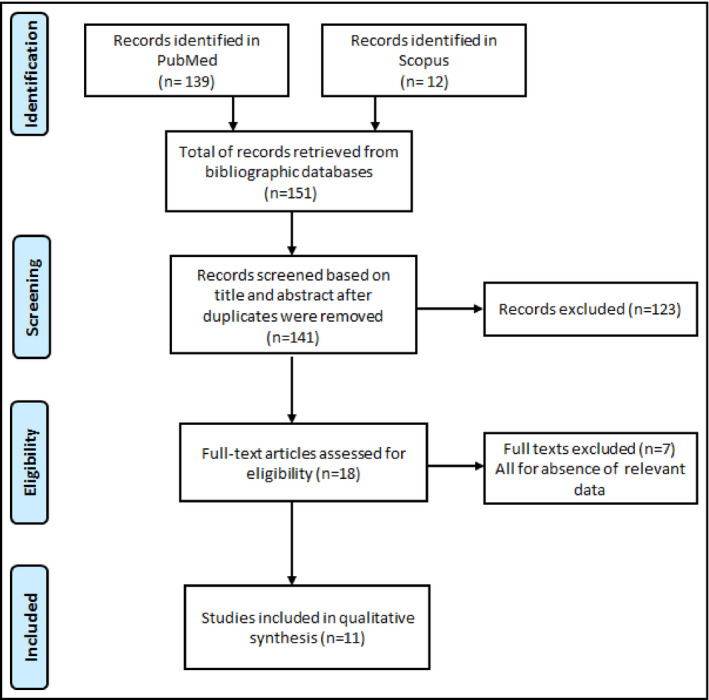

Two investigators (JJN and UFN) independently screened the titles and abstracts of articles retrieved from literature search, and the full‐texts of articles found potentially eligible were obtained and further assessed for final inclusion (Figure 1). All disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart

2.3. Data extraction and management

Two investigators (JJN and JRNkeck) independently extracted data from each included study using the data extraction form. Information extracted included first author's name, year of publication, period of data collection, country, study design (cross‐sectional or case‐control), origin of participants (hospital or community), sample size, mean or median age and age range, proportion of female participants, method of BP measurement, diagnosis criteria for WCH and MH, and proportions participants with WCH or MH. Disagreements between investigators were resolved through consensus following a discussion.

2.4. Assessment of methodological quality of studies

Risk of bias of included studies was evaluated using an adapted version of the tool developed by Hoy and colleagues.7 A score of 1 (yes) or 0 (no) was assigned for each item, and scores summed across items to generate an overall quality score that ranged from 0 to 10 (Table S1). Studies were then classified as having a low (8‐10), moderate (5‐7), or high (0‐4) risk of bias. Two investigators (JJN and UFN) independently assessed study methodological quality, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

2.5. Data synthesis and analysis

Data were analyzed using the “meta” packages of the statistical software R (version 3.3.3, The R Foundation for statistical computing). Unadjusted prevalence was calculated based on the information of crude numerators and denominators provided by individual studies. To keep the effect of studies with extremely small or extremely large prevalence estimates on the overall estimate to a minimum, the variance of the study‐specific prevalence was stabilized with the Freeman‐Tukey double arc‐sine transformation before pooling the data with the random‐effects meta‐analysis model.8 Symmetry of funnel plots and Egger test was done to assess the presence of publication and selective reporting bias.9 A P‐value <.10 was considered indicative of statistically significant publication bias. Heterogeneity across included studies was assessed using the χ² test for heterogeneity with a 5% level of statistical significance,10 and by using the I² and H statistics for which a value of 50% for I² was considered to imply substantial heterogeneity.11 When substantial heterogeneity was detected (P < .05), subgroup analyses to investigate the possible sources of heterogeneity were performed. We considered setting and areas for subgroup analyses. Inter‐rater agreements between investigators for study inclusion and methodological quality assessment were assessed using Kappa Cohen's coefficient.12

3. RESULTS

3.1. review process

Bibliographic searches identified 151 records (12 in Scopus and 139 in PubMed). After elimination of duplicates, title and abstracts of remaining records were screened, and from them, 18 records were selected and their full‐texts downloaded for further screening. Eleven articles13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 were found eligible based on full‐text screening and were therefore included in the meta‐analysis (Figure S1). The inter‐rater agreement for study inclusion and data extraction between investigators was κ = 0.91 and 0.82, respectively.

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

In total, 8082 participants were included. Regarding methodological quality, all included studies had a low‐risk of bias. Data were from eight countries: South Africa (n = 4),13, 14, 15, 16 Algeria (n = 1),17 Cameroon (n = 1),18 Kenya (n = 1),19 Morocco (n = 1),20 Nigeria (n = 1),21 Seychelles (n = 1),22 and Tanzania (n = 1).23 Participants were included from 1999 to 2015. The proportion of males varied between 36% and 64%. The mean/median age varied from 43.5 to 76 years. Eight studies were conducted in urban areas, 2 studies in rural areas, and 1 study did not report the area. Participants were recruited from the community in seven studies and from hospital in four studies. Seven studies were cross‐sectional, 4 case‐control, and 1 baseline data of cohort study. Diagnosis of white coat and masked hypertension was based on CBPM and ABPM in 10 studies and CBPM and HBPM in 1 study. Tables S2, S3 and S4 show individual characteristics of included studies.

3.3. Prevalence of white coat and masked hypertension

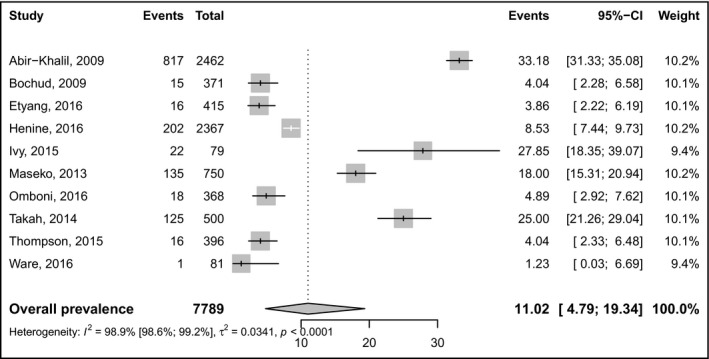

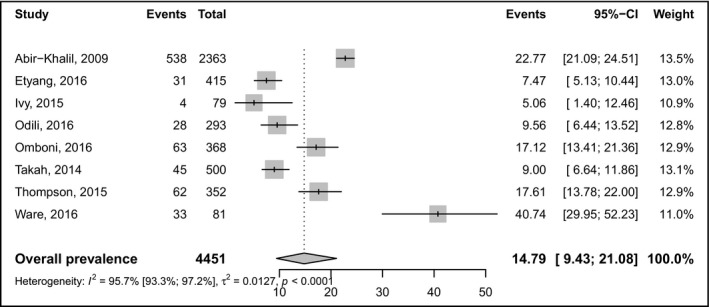

Table 1 summarizes white coat and masked prevalence statistics. The prevalence of masked hypertension was 11% (95% CI: 4.7‐19.3; 10 studies) in a pooled sample of 7789 individuals (Figure 2). The prevalence of white‐coat hypertension was 14.8% (95% CI: 9.4‐21.1; 8 studies) in a pooled sample of 4451 individuals (Figure 3). There was no difference on the prevalence of masked and white coat hypertension between studies in which participants were recruited from the community and the hospital (Figures S1 and S2). The prevalence of masked hypertension was higher in urban compared to rural areas (Figure S3). There was no difference on the prevalence of white coat hypertension between studies conducted in rural compared to urban areas (Figure S4). There was no asymmetry for funnel plots investigating publication bias (Figures S5 and S6), corroborated by the Egger tests (Table 1). Substantial heterogeneity was found for all analyses except for subgroup analysis of masked hypertension in rural areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of white coat and masked hypertension prevalence in Africa

| N studies | N participants | Prevalence % (95% confidence interval) | I² (95% confidence interval) | H (95% confidence interval) | P heterogeneity | P Egger test | P difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White coat hypertension | ||||||||

| All | 10 | 7789 | 11 (4.7‐19.3) | 98.9 (98.6‐99.2) | 9.7 (8.6‐10.9) | <.0001 | .258 | |

| By site of recruitment | ||||||||

| Community | 6 | 2092 | 7.9 (2.7‐15.3) | 96.2 (93.9‐97.7) | 5.1 (4‐6.5) | <.0001 | .706 | .275 |

| Hospital | 4 | 5697 | 16.2 (4.7‐33) | 99.5 (99.3‐99.6) | 13.8 (11.7‐16.2) | <.0001 | .794 | |

| By area | ||||||||

| Rural | 2 | 494 | 13.2 (0‐44.2) | 97.1 (92.5‐98.9) | 5.9 | <.0001 | NA | .896 |

| Urban | 7 | 6924 | 11.7 (4.4‐21.9) | 99.1 (98.9‐99.3) | 10.7 (9.3‐12.3) | <.0001 | .387 | |

| Masked hypertension | ||||||||

| All | 8 | 4451 | 14.8 (9.4‐21.1) | 95.7 (93.1‐97.2) | 4.8 (3.9‐5.9) | <.0001 | .244 | |

| By site of recruitment | ||||||||

| Community | 5 | 1220 | 14.1 (6.9‐23.2) | 93.5 (87.8‐96.6) | 3.9 (2.9‐5.4) | <.0001 | .509 | .790 |

| Hospital | 3 | 3231 | 15.9 (8.2‐25.7) | 96.8 (93.4‐98.4) | 5.6 (3.9‐8) | <.0001 | .395 | |

| By area | ||||||||

| Rural | 2 | 494 | 6.9 (4.8‐9.4) | 0 | 1 | .517 | NA | .0006 |

| Urban | 6 | 3957 | 17.9 (11.9‐24.9) | 95.2 (91.9‐97.1) | 4.6 (3.5‐5.9) | <.0001 | .527 | |

Figure 2.

Pooled prevalence of masked hypertension. Events left forest = number of cases, event right forest = prevalence

Figure 3.

Pooled prevalence of white‐coat hypertension. Events left forest = number of cases, event right forest = prevalence

4. DISCUSSION

Results from this systematic review and meta‐analysis of 11 studies revealed a pooled prevalence of 11% for white coat hypertension, and 14.8% for masked hypertension in Africa. We also found no difference between prevalence rates according to site (community‐based vs hospital‐based studies) except for masked hypertension, though the number of studies in each subgroup was low. Our data indicate the contributions of white coat hypertension and masked hypertension to the growing burden of hypertension in Africa.

Our prevalence of white coat hypertension is slightly lower than what has been reported for Europeans, between 15%‐30%;24, 25 however, it may not contribute in explaining the blood pressure differences between Blacks and Whites. In fact, Agyemang et al. demonstrated that the white coat effect might not differ significantly between people of African descent and White people of European origin.26 Concerning masked hypertension, our prevalence appears higher than findings from an international cohort regrouping 11 populations, pointing the prevalence of masked hypertension at 7.5% among normotensive individuals.27 Contrariwise, a previous meta‐analysis on masked hypertension revealed a pooled prevalence of 16.8%,28 not far from our 14.8%; this prevalence equaled 7% among children and 19% among adults.28

Our results indicate that in Africa, more than 1 in 10 patients would be treated as hypertensive when he/she is probably not. Accordingly, our data claim in favor of an overburdened picture of hypertension in Africa due to a high prevalence of white coat hypertension. The misclassification of patients with white coat hypertension as being truly hypertensive may penalize them for employment and insurance rating; additionally, they may be prescribed unnecessary lifelong treatment with potential adverse effects that can be seriously debilitating, particularly for elder people.4 On the other hand, misdiagnosis of white coat hypertension will result in a large expenditure on unnecessary drugs,29 which would be particularly disastrous for the African continent where drugs to treat hypertension are direly unavailable and/or inaccessible/unaffordable.30, 31 Moreover, results from the International Database on Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes (IDACO) study showed that participants with untreated white coat hypertension had similar incidence rates of cardiovascular events in comparison to untreated normotensive controls,32 in line with reports from Fagard and Cornelissen.33 By contrast, a recent publication indicated that untreated white coat hypertension is associated with long‐term risk of cardiovascular disease and total mortality,34 corroborating somehow Briasoulis et al.'s meta‐analysis conclusions.35 Therefore, should we treat patients with white coat hypertension? To date, this question remains unanswered and we hope that future randomized controlled trials will address this issue. Nonetheless, clinicians should bear in mind that subjects with white coat hypertension who are not treated may present an increased cardiovascular risk, though smaller than that for subjects with sustained hypertension, depending substantially on associated cardiometabolic risk factors.4 Therefore, patients with white coat hypertension should be closely followed‐up to detect any evidence of progression towards sustained hypertension.24

A striking finding from this meta‐analysis was that more than 1 in 10 Africans, presumably classified as normotensives, would be missed and not treated as hypertensive while clearly having the disease. This is very preoccupying, considering the increased cardiovascular risk presented by subjects diagnosed with masked hypertension. Indeed, there is strong evidence indicating an increased risk of target organ damage, cardiovascular, and renal morbidity among individuals with masked hypertension, with an overall risk of cardiovascular disease narrowing that of sustained hypertensives.24, 33, 36, 37 Therefore, it appears of great importance to identify those people who present masked hypertension and offer them the proper treatment, especially in urban areas where the burden is higher. Previous reports have identified some groups as being at high risk of presenting masked hypertension: elderly patients (with a male predominance, people with a high‐normal systolic and diastolic office BP, smokers, excessive alcohol drinkers, sedentary and obese individuals, those with metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, shortened sleep time or obstructive sleep apnea, mental stress at work or at home, hypochondria, and people with electrocardiographic left‐ventricular hypertrophy.5, 38

Our results are a claim in favor of the vulgarization of 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) in routine clinical practice throughout Africa, in line with a position paper from the European Society of Hypertension released in 2013.24 ABPM is indeed the gold standard to diagnose both white coat hypertension and masked hypertension in the many conditions where they might occur. As a matter of fact, although conventional BP measurement at office or clinic seems simple and convenient to use, its limitations in the diagnosis, monitoring of 24‐hour BP variations (especially at night), and prediction of cardiovascular events39 led to the development of out‐of‐office BP monitoring techniques, notably the ABPM and the home BP monitoring (HBPM). However, although ABPM has shown superiority over HBPM, especially in diagnosing white coat hypertension,24 it was shown that these 2 methods yielded similar performances in predicting cardiovascular events and evaluating response to treatment.40, 41 Furthermore, HBPM is less costly, more accessible and convenient for patient use, and has greater potential in achieving optimal BP control and treatment compliance, especially in well‐informed and cooperative patients who understand the benefits of self‐monitoring.42 HBPM has therefore been suggested as a reliable alternative to ABPM in situations where the latter technique is uncomfortable for the patient, unavailable, or unaffordable.43 As these latter 2 satiations apply to the African continent, stepping‐up HBPM use could be of substantial help in curbing the burden of hypertension throughout the continent.44 In this regard, BP monitors could be subsidized to be sold at affordable prices in the continent. However, HBPM also has some practical issues regarding its implementation over at least 1 week and this technique ignores nighttime BP whose apparent role in events development is really important.

However, these results need to be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First and common to systematic reviews of this kind, there was a high statistical heterogeneity between studies, which we could not explain by the study site or setting; on the other hand, the low number of studies included did not permit to carryout more subgroup and meta‐regression analyses. Second, several included studies also treated the patients, and therefore showed differences in diagnostic procedure and BP device use across studies, adding to the overall heterogeneity of our findings. Third, not all regions of Africa were equally represented, possibly hindering the translatability of our results to the entire continent. Notwithstanding and to the very best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta‐analysis summarizing the existing knowledge on white coat and masked hypertension prevalence rates in Africa. Using rigorous methodological and statistical procedures, we searched the major electronic databases and identified 11 studies presenting a low‐to‐moderate risk of bias.

5. CONCLUSIONS

White coat hypertension and masked hypertension seem to be frequent in African populations, thus prompting the adoption of out‐of‐office BP measurement in routine clinical practice. Considering that ABPM is costly and/or unavailable in Africa, we suggest that HBPM be proposed to each patient diagnosed with hypertension and to individuals known at high risk of masked hypertension.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.J.N. conceived the study. J.J.N. did the literature search. J.J.N., J.R. Nkeck, and U.F.N. selected the studies and extracted the relevant information. J.J.B. and J.J.N. synthesized the data. J.J.N., J.R. Nansseu, and J.J.B. wrote the first draft of the paper. J.J.N., J.R. Neck, J.R. Nansseu, U.F.N., and J.J.B. critically revised successive drafts of the paper and approved its final version. J.J.N. is the guarantor of the review.

Supporting information

Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Nkeck JR, Nyaga UF, Bigna JJ. Prevalence of white coat and masked hypertension in Africa: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20:1165–1172. 10.1111/jch.13321

REFERENCES

- 1. GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators . Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990‐2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659‐1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . A Global Brief on Hypertension: Silent Killer, Global Public Health Crisis. World Health Day 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atakle F, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Taye B, Echouffo‐Tcheugui JB, Kengne AP. Burden of undiagnosed hypertension in sub‐Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Hypertension. 2015;65:291‐298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Franklin SS, Thijs L, Hansen TW, O'Brien E, Staessen JA. White‐coat hypertension: new insights from recent studies. Hypertension. 2013;62:982‐987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Franklin SS, O'Brien E, Thijs L, Asayama K, Staessen JA. Masked hypertension: a phenomenon of measurement. Hypertension. 2015;65:16‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006‐1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:934‐939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta‐analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;1:974‐978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;13:629‐634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101‐129. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539‐1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37:360‐363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maseko MJ, Woodiwiss AJ, Libhaber CD, Brooksbank R, Majane OH, Norton GR. Relations between white coat effects and left ventricular mass index or arterial stiffness: role of nocturnal blood pressure dipping. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:1287‐1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Omboni S, Aristizabal D, De la Sierra A, et al. Hypertension types defined by clinic and ambulatory blood pressure in 14 143 patients referred to hypertension clinics worldwide. Data from the ARTEMIS study. J Hypertens. 2016;34:2187‐2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thompson JE, Smith W, Ware LJ, et al. Masked hypertension and its associated cardiovascular risk in young individuals: the African‐PREDICT study. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:158‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ware LJ, Rennie KL, Gafane LF, et al. Masked hypertension in low‐income South African adults. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:396‐404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henine N, Kichou B, Kichou L, et al. Prevalence of true resistant hypertension among uncontrolled hypertensive patients referred to a tertiary health care center. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 2016;65:191‐196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takah N, Dzudie A, Ndjebet J, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure measurement in the main cities of Cameroon: prevalence of masked and white coat hypertension, and influence of body mass index. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Etyang AO, Warne B, Kapesa S, et al. Clinical and epidemiological implications of 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring for the diagnosis of hypertension in Kenyan adults: a Population‐Based Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:pii: e004797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abir‐Khalil S, Zaîmi S, Tazi MA, Bendahmane S, Bensaoud O, Benomar M. Prevalence and predictors of white‐coat hypertension in a large database of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:400‐407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Odili AN, Thijs L, Hara A, et al. Prevalence and determinants of masked hypertension among black nigerians compared with a reference population. Hypertension. 2016;67:1249‐1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bochud M, Bovet P, Vollenweider P, et al. Association between white‐coat effect and blunted dipping of nocturnal blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:1054‐1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ivy A, Tam J, Dewhurst MJ, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to assess the white‐coat effect in an elderly East African population. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015;17:389‐394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, et al. European Society of Hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1731‐1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gorostidi M, Vinyoles E, Banegas JR, de la Sierra A. Prevalence of white‐coat and masked hypertension in national and international registries. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agyemang C, Bhopal R, Bruijnzeels M, Redekop WK. Does the white‐coat effect in people of African and South Asian descent differ from that in white people of European origin? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Blood Press Monit. 2005;10:243‐248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brguljan‐Hitij J, Thijs L, Li Y, et al. Risk stratification by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring across JNC classes of conventional blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:956‐965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Verberk WJ, Kessels AGH, de Leeuw PW. Prevalence, causes, and consequences of masked hypertension: a meta‐analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:969‐975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lovibond K, Jowett S, Barton P, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of options for the diagnosis of high blood pressure in primary care: a modelling study. Lancet. 2011;378:1219‐1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jingi AM, Noubiap JJN, Ewane Onana A, et al. Access to diagnostic tests and essential medicines for cardiovascular diseases and diabetes care: cost, availability and affordability in the West Region of Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e111812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khatib R, McKee M, Shannon H, et al. Availability and affordability of cardiovascular disease medicines and their effect on use in high‐income, middle‐income, and low‐income countries: an analysis of the PURE study data. Lancet. 2016;387:61‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Franklin SS, Thijs L, Hansen TW, et al. Significance of white‐coat hypertension in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: a meta‐analysis using the International Database on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes population. Hypertension. 2012;59:564‐571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fagard R, Cornelissen V. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white‐coat, masked and sustained hypertension versus true normotension: a meta‐analysis. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2193‐2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang Y, Huang W, Mai W, et al. White‐coat hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and total mortality. J Hypertens. 2017;35:677‐688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Briasoulis A, Androulakis E, Palla M, Papageorgiou N, Tousoulis D. White‐coat hypertension and cardiovascular events: a meta‐analysis. J Hypertens. 2016;34:593‐599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Minutolo R, Agarwal R, Borrelli S, et al. Prognostic role of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in patients with nondialysis chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1090‐1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hänninen MR, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Kesäniemi YA, Kähönen M, Jula AM. Target organ damage and masked hypertension in the general population: the Finn‐Home study. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1136‐1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hänninen MR, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Mattila AK, Jula AM. Determinants of masked hypertension in the general population: the Finn‐Home study. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1880‐1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jin Y, Bies R, Gastonguay MR, Stockbridge N, Gobburu J, Madabushi R. Misclassification and discordance of measured blood pressure from patient's true blood pressure in current clinical practice: a clinical trial simulation case study. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2012;39:283‐294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bliziotis IA, Destounis A, Stergiou GS. Home versus ambulatory and office blood pressure in predicting target organ damage in hypertension: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1289‐1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fagard RH, Van Den Broeke C, De Cort P. Prognostic significance of blood pressure measured in the office, at home and during ambulatory monitoring in older patients in general practice. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:801‐807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gosse P, Coulon P. Ambulatory or home measurement of blood pressure? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2009;11:234‐237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yano Y, Bakris GL. Recognition and management of masked hypertension: a review and novel approach. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2013;7:244‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ndip Agbor V, Temgoua MN, Noubiap JJN. Scaling up the use of home blood pressure monitoring in the management of hypertension in low‐income countries: a step towards curbing the burden of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:786‐789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials