Abstract

To compare central and brachial blood pressure (BP) in the association of target organ damage (TOD) in a community‐based elderly population, 1599 (aged 71.4 ± 6.1 years) participants in northern Shanghai were recruited. TOD included left ventricular hypertrophy (n = 1556), left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (n = 1524), carotid plaque (n = 1558), arteriosclerosis (n = 1485), and microalbuminuria (n = 1516). Both central and brachial BP significantly correlated with TOD. In full‐model regression, central BP was significantly associated with all TOD (P ≤ .04), whereas brachial BP was only significantly associated with left ventricular hypertrophy and arteriosclerosis (P ≤ .01). Similarly, in stepwise regression, central BP was significantly associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, arteriosclerosis, and microalbuminuria (P ≤ .04), while brachial BP was not associated with any TOD. Receiver operating characteristic analyses indicated that central BP identified arteriosclerosis and microalbuminuria better than brachial BP (P ≤ .01). In conclusion, central BP showed superiority over brachial BP in the association of hypertensive TOD in a community‐based elderly population.

Keywords: brachial blood pressure, central blood pressure, target organ damage

1. INTRODUCTION

High blood pressure (BP) is a well‐established cardiovascular risk factor, and cardiovascular events have been identified as a major cause of mortality and disability worldwide.1 The assessment of brachial BP has been embedded in routine clinical practice because of its ease of measurement, and current antihypertensive treatment based on brachial BP leads to the significant reduction of cardiovascular events.2, 3 However, from a pathophysiological point of view, central or aortic BP is the direct load to which target organs are exposed, and brachial BP, per se, is a surrogate of central BP when central BP is not available. Growing clinical evidence has demonstrated that central BP is more significantly related to target organ damage (TOD) and future cardiovascular events than brachial BP,4, 5 and our previous findings also support these results.6, 7 In addition, with the development of noninvasive devices for the assessment of central BP, central BP can be measured more easily than in the past, and physicians can get more information about BP apart from regular brachial BP measurements. Meanwhile, asymptomatic TOD, including left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), carotid wall thickening or plaque, carotid‐femoral pulse wave velocity (cfPWV), and microalbuminuria, has clinical significance for the prognosis of patients, and guidelines recommend that these TODs should be assessed in patients with hypertension.2, 3 Although it was reported that central rather than brachial BP was better associated with TOD in multiple populations, the superiority of central over brachial BP is still under discussion. In 2007, Dart and colleagues8 reported that in 479 patients with hypertension from the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Trial, the reductions of central and brachial BP after antihypertensive treatment were similar, and central BP did not show superiority over brachial BP. Current data on central BP focus more on patients with hypertension, and the data in general geriatric population are limited. In our unselected community‐dwelling geriatric population, we hypothesized that central BP would comprehensively be better associated with TOD than brachial BP. This study was realized within the context of the observational Northern Shanghai Study.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and population

The Northern Shanghai Study (registry No. NCT02368938) is an observational single‐center prospective study. This study is a longitudinal epidemiologic trial recruiting community‐based elderly (≥65 years) patients in northern Shanghai, and aimed to build a Chinese cardiovascular risk score for the elderly. All participants underwent BP and global cardiovascular risk assessment at the beginning of the study and will repeat it at the 5‐ and 10‐year follow‐up, including both conventional cardiovascular risk factors and asymptomatic TOD. Patients were enrolled if they were: (1) 65 years or older; (2) local residents from urban communities in the north of Shanghai; and (3) were eligible for long‐term follow‐up and willing to sign the informed consent. The exclusion criteria were: (1) severe cardiac insufficiency (New York Heart Association functional class IV) or renal failure (chronic kidney disease > 4); (2) malignant tumor or life expectancy <5 years; (3) stroke history within 3 months; and (4) unwillingness or inability to adhere to the long‐term follow‐up. All participants were asked to refrain from food and any vasoactive substance or medication in the morning of the examination, and participants or their legal caregivers signed individual informed consents. This study began in August 2014 and is ongoing. It was granted ethical approval by the local ethics committee.

2.2. Medical history and BP assessment

A standardized structured questionnaire was performed by well‐trained physicians to obtain medical and family history, including smoking, hypertension or the use of antihypertensive agents, diabetes mellitus, and history of stroke or renal disease. In the morning (8 am to 10 am) in a temperature‐controlled room (22–27°C), brachial BP was measured three times, with an interval of 5 minutes, by an experienced operator, with a mercury sphygmomanometer after a 10‐minute rest in patients in the sitting position. The average was calculated and used in subsequent analyses except for PWV measurement. Hypertension was defined as brachial systolic BP (SBP) ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mm Hg or the use of antihypertensive agents. Later, central BP was assessed by another experienced operator with a validated device (VP‐1000, Omron). The interval between brachial and central BP measurements was within 30 minutes. Central BP together with four‐limb BP was measured by this device automatically and the measurement was taken once for each participant.

2.3. Anthropometric and biochemical measurements

Body height (in meters) and body weight (in kilograms) were measured by a trained technician, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight divided by squared body height. Fasting blood and urine samples were obtained and a variety of biochemical measurements, including plasma glucose, lipid profiles, urinary creatinine, and urinary albumin excretion, were conducted in the laboratory of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital. Urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio (UACR) was calculated and microalbuminuria was defined as a UACR ≥ 30 g/mol.

2.4. Echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography

One experienced operator who was blind to participants’ characteristics performed all of the echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography using a MyLab 30 cardiovascular machine (ESAOTE SPA), with a 3.5‐mol L−1 probe and a 7.5‐mol L−1 probe, respectively.

LV dimensions and mass were measured through transthoracic echocardiography. According to recommendations by the American Society of Echocardiography,9 LV mass (LVM) was calculated from two‐dimensionally guided M‐mode echocardiograms. End‐diastolic LV internal diameter and septal and posterior wall thickness were measured. LVM was calculated as the formula: LVM (g) = 0.8 × {1.04 × [(LV internal diameter + posterior wall thickness + septal wall thickness)3 − (LV internal diameter)3]} + 0.6, indexing for body surface area as LVM index (LVMI). LVMI ≥ 115 g/m2 in men or LVMI ≥ 95 g/m2 in women was considered as LVH.

Left atrial volume was measured by the American Society of Echocardiography–recommended method and standardized to body surface area as left atrial volume index.9 Transmitral early diastolic peak flow (E) was measured by pulsed wave Doppler, and early diastolic movement (Ea) in the lateral side was measured by tissue Doppler. The ratio of E and Ea waves (E/Ea) was calculated. The definition of LV diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) was E/Ea ≥ 15, or E/Ea was between eight and 15 and with any of the following evidence: (1) left atrial volume index > 40 mL/m2; and (2) LVMI > 149 g/m2 in men or LVMI > 122 g/m2 in women.

Carotid ultrasonography was performed to assess the intima‐media thickness (IMT). IMT was measured on the left common carotid artery plaque‐free segment, approximately 2 cm to the origin of bifurcation. The measurement was taken three times and the average was calculated for further analysis. Both carotid arteries were scanned to identify carotid plaque, which was defined as focally increased IMT > 50% of the surrounding wall thickness.

2.5. cfPWV measurement

Two experienced operators measured the cfPWV with a validated device (SphygmoCor, AtCor Medical) according to the European Expert Consensus on Arterial Stiffness.10 After resting for 10 minutes in a quiet temperature‐controlled room, participants underwent BP measurement twice recorded by an OMRON device (HEM‐7211) in the supine positon with a 3‐minute interval. The average of these two readings was input into the SphygmoCor device to calculate PWV. Both the distance from the suprasternal notch to the common femoral artery and the distance from the right carotid artery to the suprasternal notch were measured and the travelling distance was calculated as the difference between these two distances ([suprasternal notch to the common femoral artery]–[carotid artery to the suprasternal notch]). After the simulation ECG conduction, pulse waves were recorded consecutively at the right common carotid and the right femoral arteries. The SphygmoCor device automatically calculated cfPWV and offered an operator index after all necessary information was obtained, including BP, travelling distance, ECG, and pulse waves at two sites. Results with an operator index > 80% were considered reliable. The cutoff value was 12 m/s, and participants with PWV ≥ 12 m/s were considered to have arteriosclerosis.

2.6. Statistical analysis

A two‐tailed P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical software SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc) was used for all statistical analyses. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and categorical variables as absolute numbers and percentages. Differences between two groups were tested by Student t test for continuous variables and by chi‐square test for proportions.

The bivariate relationships of brachial and central BP and measures of TOD were analyzed with Pearson correlation coefficient. Differences were compared by the Fisher transformed z test. Multiple linear and logistic regressions were performed to assess the associations between a one‐SD increment in central or brachial BP and TOD with a stepwise method (likelihood ratio method, with variables out by P > .1). Only one brachial or central BP parameter was introduced at a time in each model and adjusted for potential confounders because of the substantial colinearity between different BP indices. To explore whether central pressure discriminates TOD better than brachial, receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed in all participants and in those without antihypertensive agents, and the C‐statistic was applied for the comparison between the area under the curves (AUCs).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of participants

Residents older than 65 years from 10 communities located in northern Shanghai were screened, and 1721 individuals were eligible and invited at random to this study, of whom 1599 (responding rate 92.9%) participated, including 711 (45.5%) men, 366 (22.9%) smokers, 843 (52.7%) with hypertension, and 312 (19.5%) with diabetes mellitus. A total of 1590 participants were finally involved in the present analysis, since the other nine participants were without available central BP data. Table 1 shows the characteristics of all participants. Over half of the participants had hypertension, approximately 34.3% participants had cardiovascular diseases, and nearly 20% had diabetes mellitus. According to the recommendations from Herbert and colleagues,11 the reference values of central SBP, namely 128 mm Hg (age 60–69 years), 135 mm Hg (men ≥ 70 years), and 138 mm Hg (women ≥ 70 years), were used to identify central hypertension. Based on these cutoff values, there were 675 (42.2%) participants with central hypertension. Only 508 (31.8%) participants had both central hypertension and peripheral hypertension. A total of 335 (21.0%) participants had peripheral but not central hypertension, and 167 (10.4%) participants had central but not peripheral hypertension.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the population (N = 1599)

| Characteristics | |

| Age, y | 71.4 ± 6.1 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.9 ± 3.5 |

| Drinker, No. (%) | 237 (14.8) |

| Smoker, No. (%) | 366 (22.9) |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mmol/L | 5.69 ± 1.70 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.22 ± 1.01 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.61 ± 0.93 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.38 ± 0.36 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 3.20 ± 0.85 |

| Brachial systolic BP, mm Hg | 134.3 ± 17.7 |

| Brachial diastolic BP, mm Hg | 78.9 ± 9.1 |

| Central systolic BP, mm Hg | 130.2 ± 18.5 |

| Central diastolic BP, mm Hg | 74.4 ± 9.5 |

| Asymptomatic target organ damage | |

| Left ventricular mass index, g/m2 | 90.0 ± 28.6 |

| Carotid intima‐media thickness, μm | 612.1 ± 148.2 |

| Plaque in carotid arteries, No. (%) | 1085 (68) |

| Pulse wave velocity, m/s | 9.42 ± 2.31 |

| Creatinine clearance rate, % | 92.4 ± 21.7 |

| Urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio, mg/g | 23.7 (13.5–45.9) |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 843 (52.7) |

| CVD, No. (%) | 549 (34.3) |

| Stroke or TIA, No. (%) | 318 (19.9) |

| Renal disease, No. (%) | 132 (8.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus, No. (%) | 312 (19.5) |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or number (percentage) except for urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio, which is expressed as median (interquartile range). Creatinine clearance rate was calculated with the modified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula for Chinese.

3.2. Univariate correlations of TOD and central and brachial SBP

In general, central SBP was significantly associated with all parameters regarding asymptomatic TOD, namely LVMI, E/Ea, left IMT, PWV, and UACR (P ≤ .01). Similar results were obtained in the correlations of brachial SBP with TOD (P < .001), except for UACR. As shown in Table 2, Fisher transformed z test was performed to compare the correlation coefficients of central and brachial BP in their association with TOD. PWV exhibited greater correlation coefficients with central BP than with brachial BP (0.46 vs 0.36, P = .005), while other TOD parameters showed similar correlation coefficients (P ≥ .23).

Table 2.

Correlations of BP with target organ damage indexes

| LVMI | E/Ea | LIMT | PWV | UACR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P value | R | P value | R | P value | R | P value | R | P value | |

| Brachial systolic BP | .21 | <.001 | .20 | <.001 | .11 | <.001 | .36 | <.001 | .04 | .10 |

| Central systolic BP | .24 | <.001 | .20 | <.001 | .11 | <.001 | .46 | <.001 | .07 | .01 |

| z test (P value) | −0.68 (.23) | 0.09 (.45) | 0.13 (.42) | −2.53 (.005) | −0.68 (.23) | |||||

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; E/Ea, ratio of E and Ea waves; LIMT, left intima‐media thickness; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; PWV, pulse wave velocity; UACR, urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio.

Pearson correlation analyses and Fisher transformed z test were performed to compare the coefficients.

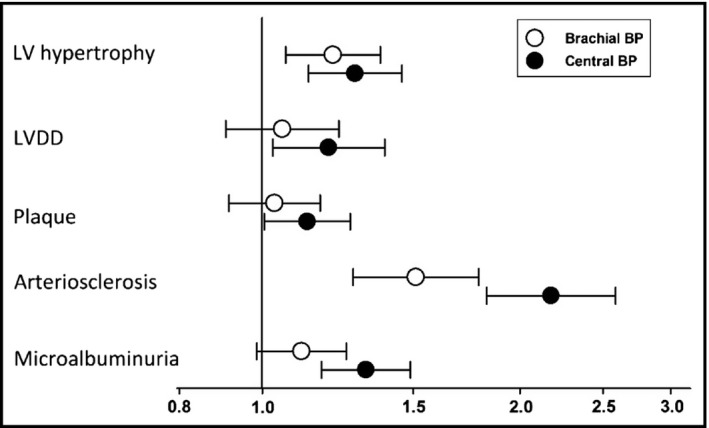

3.3. Full‐model logistic regression of TOD and brachial SBP

Full‐model logistic regression was performed to assess the association of BP with TOD. Because of the substantial colinearity between central and brachial BP, central or brachial BP parameters were introduced once in each model. As shown in the Figure, after adjustment for age, sex, body mass index, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, antihypertensive treatment, low‐density lipoprotein level, and blood glucose level, both central and brachial BP were significantly associated with LVH, with odds ratio (ORs) of 1.014 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.007–1.021] and 1.011 (95% CI, 1.004–1.019), respectively. As for LVDD, only central BP was significantly associated with LVDD, with an OR of 1.010 (95% CI, 1.002–1.018), while the association between brachial BP and LVDD did not achieve statistical significance. Similar results were found in the association of BP indexes with carotid plaque and microalbuminuria. Central BP was significantly associated with carotid plaque and microalbuminuria (OR, 1.007 [95% CI, 1.001–1.013] and 1.015 [95% CI, 1.008–1.022], respectively), but brachial BP was not. Arteriosclerosis exhibited significant associations with both central and brachial BP, while central BP, as compared with brachial BP, was more strongly associated with arteriosclerosis (OR, 1.043 [95% CI, 1.033–1.053] vs 1.024 [95% CI, 1.014–1.034], respectively; P < .001).

Figure 1.

Full‐model logistic regression analysis of systolic blood pressure (BP) as independent variable (brachial or central, respectively) and target organ damage indexes: logistic regressions were performed to investigate the association of: (1) left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, (2) LV diastolic dysfunction (DD), (3) carotid plaque, (4) arteriosclerosis, and (5) microalbuminuria with one‐SD increment of brachial and central systolic BP, respectively. The potential confounders, including age, sex, body mass index, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, antihypertensive treatment, and blood low‐density lipoprotein and blood glucose levels, together with brachial or central BP, were put into respective models. LV hypertrophy, LVDD, and carotid plaque were assessed by echocardiography. Arteriosclerosis was defined as pulse wave velocity over 12 m/s, and microalbuminuria was defined as urinary‐albumin creatinine ratio over 30 mg/mmol

3.4. Multivariate correlation of BP with TOD

Multiple stepwise linear regression models and multiple stepwise binary logistic models were constructed to assess the independent association between BP and TOD (Table 3). Given the same reason in full‐model logistic regression, central or brachial BP parameter was introduced once in each model. After adjustment for the same potential confounders in full‐model logistic regression, central SBP was significantly associated with LVMI, E/Ea, left IMT, and PWV (P ≤ .001), while brachial SBP was only significantly associated with E/Ea and PWV. Neither central nor brachial SBP entered the model in the regression of UACR. In stepwise logistical regression, central SBP was significantly associated with LVH, LVDD, arteriosclerosis, and microalbuminuria. However, brachial SBP did not show any statistical significance in the association of TOD after adjustment for potential confounders.

Table 3.

Stepwise multiple linear and logistic regression analysis of BP and target organ damage indexes

| Target organ damages | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear regression analysis | ||||||||||

| LVMI | E/Ea | LIMT | PWV | UACR | ||||||

| β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | |

| Brachial systolic BP | – | – | 0.026 | <.001 | – | – | 0.010 | .005 | – | – |

| Central systolic BP | 0.21 | <.001 | 0.020 | .001 | 0.57 | .007 | 0.039 | <.001 | – | – |

| Logistic regression analysis | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVH | LVDD | Plaque | Arteriosclerosis | Microalbuminuria | |||||||

| OR | CI | OR | CI | OR | CI | OR | CI | OR | CI | ||

| Brachial systolic BP | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Central systolic BP | 1.014 | 1.007–1.021 | 1.010 | 1.002–1.018 | – | – | 1.043 | 1.033–1.053 | 1.015 | 1.008–1.021 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Stepwise linear and logistic regressions were performed to investigate the association of: (1) left ventricular mass index (LVMI) and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), (2) ratio of E and Ea waves (E/Ea) and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (LVDD), (3) left intima‐media thickness (LIMT) and carotid plaque, (4) pulse wave velocity (PWV) and arteriosclerosis, and (5) urinary albumin‐creatinine ratio (UACR) and microalbuminuria with a one‐SD increment of brachial and central blood pressure (BP), respectively. The potential confounders including age, sex, body mass index, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, antihypertensive treatment, and blood low‐density lipoprotein and blood glucose levels were put into respective models, and brachial or central BP was entered into the model with a P value < .10.

3.5. ROC curve analysis

The ROC curve analysis and further comparison by the C‐statistics analysis is presented in Table 4. There was a significantly higher discriminatory ability of central SBP to detect the presence of arteriosclerosis (AUC: 0.755 vs 0.672; P < .001) and microalbuminuria (AUC: 0.615 vs 0.578; P = .01) compared with brachial SBP (P ≤ .01). When ROC analyses were performed in patients with untreated hypertension to eliminate the effects of antihypertensive drugs, central SBP significantly better detected the presence of LVH, LVDD, arteriosclerosis, and microalbuminuria in these participants than brachial SBP.

Table 4.

ROC analyses

| LVH | LVDD | Plaque | Arteriosclerosis | Microalbuminuria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROC analysis in all participants | |||||

| Brachial SBP | 0.597 | 0.563 | 0.533 | 0.672 | 0.578 |

| Central SBP | 0.614 | 0.693 | 0.554 | 0.755 | 0.615 |

| Comparison (P value) | .25 | .065 | .13 | <.001 | .01 |

| ROC analysis in participants without antihypertensive agents (n = 800) | |||||

| Brachial SBP | 0.551 | 0.526 | 0.531 | 0.675 | 0.542 |

| Central SBP | 0.600 | 0.587 | 0.560 | 0.788 | 0.593 |

| Comparison (P value) | .03 | .006 | .15 | .004 | .02 |

Abbreviations: LVDD, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed and area under the curves were compared to explore the ability of central and brachial blood pressure in discriminating target organ damages.

4. DISCUSSION

Central SBP was obtained in elderly patients in the Northern Shanghai Study. The relationship of central BP and brachial BP with TOD was compared. Central SBP, compared with brachial SBP, after adjustment for potential confounders, was better associated with multiple TOD, including LVH, LVDD, carotid plaque, arteriosclerosis, and microalbuminuria.

SBP varies within the arterial tree, for which a significant gap exists between central and brachial SBP. According to the results of the ENIGMA study, the SBP amplification between central and brachial BP was about 20 to 30 mm Hg.12 In routine clinical practice, brachial BP is indispensable because of its great convenience and strong relationship with cardiovascular events, and current antihypertensive treatment strategy based on brachial BP has substantially reduced the incidence of cardiovascular events. However, the most important target organs, including the heart, kidney, and major arteries, are directly exposed to central rather than brachial BP. As a surrogate of central BP, brachial BP cannot accurately reflect the real central BP since it highly varies between individuals and even within individuals. Moreover, McEniery and associates13 reported that in 10 613 individuals from the Anglo‐Cardiff Collaborative Trial II, central BP values were similar between individuals with stage I hypertension and over 70% individuals with “high‐normal” brachial BP. This may partly explain the greater association of TOD and central BP rather than brachial BP.

Emerging clinical evidence supports that central BP, compared with brachial BP, is better associated with TOD. Recently, a meta‐analysis of over 6000 patients conducted by Kollias and colleagues14 showed that central BP, compared with brachial BP, was more closely associated with LVMI, carotid IMT, and PWV, and was similarly associated with urine albumin excretion. This meta‐analysis strongly revealed the superiority of central BP over brachial BP in the association with TOD. However, studies included in this meta‐analysis mainly focused on one or two target organs, and some biases may exist in these pooled data. In our study, participants received extensive assessment on TOD, and central SBP was consistently better associated with multiple TOD. This may be one of the advantages of this study.

Although central BP is better associated with TOD than brachial BP, whether central BP is better associated with cardiovascular events than brachial BP is still under debate. Several studies have reported the better predictive value of central over brachial BP. In 2007, Roman and colleagues4 reported that in 3520 community‐dwelling participants from the Strong Heart Study, central BP, compared with brachial BP, was more strongly related to LVH and cardiovascular events. Later, Pini and associates5 reported that in a similar population (398 unselected geriatric patients) from the ICARe Dicomano Study, greater central but not brachial BP predicted cardiovascular events. Moreover, in 2002, Safar and colleagues15 reported that in patients with end‐stage renal disease, only central BP had predictive value for mortality after adjustment. In contrast, Mitchell and colleagues16 reported that in over 2000 participants from the Framingham Heart Study, neither central pulse pressure or pulse pressure amplification, nor central SBP,17 showed its superiority over brachial BP in the association with future cardiovascular events. In addition, it is still not clear whether the usage of central BP to guide our treatment in daily clinical practice could improve the outcomes of patients with hypertension. To date, only two studies have been conducted on this topic and none in the elderly.18, 19 Larger clinical studies are warranted and high‐quality meta‐analysis is required.

5. STUDY LIMITATIONS

Some limitations of our study should be considered. As a cross‐sectional study, it cannot prove causal relationships between central or brachial BP and TOD, or compare the contribution of central or brachial BP to the development of TOD. Second, our study was based on community‐dwelling elderly patients, therefore the results may not be generalized to young adults, and the heterogeneity of the studied population should not be ignored. Third, although the AUC of central SBP was significantly higher than that of brachial SBP, it should be pointed out that the discriminatory power of all ROC results were not excellent. Normally, an AUC between 0.5 and 0.7, 0.7 and 0.9, and >0.9 denote poor, good, and excellent discriminatory power, respectively. Only central SBP had good discriminatory ability to detect higher cfPWV (AUC > 0.7). Fourth, the volatility of albuminuria was high; however, it was measured only once in the present analysis. Fifth, the protocols for central and brachial BP measurement were a little different. Brachial BP was measured three times with the patient in the sitting position and the average was used, while central BP was measured only once with the patient in the supine position after brachial BP measurement within 30 minutes, which may partly influence the results.

6. CONCLUSIONS

In a community‐based elderly Chinese population, central BP, compared with brachial BP, is better associated with TOD, including LVH, LVDD, PWV, left IMT, and UCAR. Our study is an important complement supporting the routine application of central BP in clinical practice.

DISCLOSURE

Editorial assistance was provided by Jialing Wang of Shanghai Wall Street English Education Institute Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China, for free.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that may inappropriately influence their work. There is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service, and/or company that may be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the present article.

Chi C, Yu X, Auckle R, et al. Hypertensive target organ damage is better associated with central than brachial blood pressure: The Northern Shanghai Study. J Clin Hypertens. 2017;19:1269–1275. 10.1111/jch.13110

Funding information

This study was supported by the Shanghai municipal government (grant No. 2013ZYJB0902; 15GWZK1002, Shanghai, China). Dr Yi Zhang was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (grant No. 81670377, Beijing, China).

Contributor Information

Yi Zhang, Email: yizshcn@gmail.com.

Yawei Xu, Email: xuyaweicn@aliyun.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;380:2224‐2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Blood Press. 2013;22:193‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507‐520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, et al. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2007;50:197‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pini R, Cavallini MC, Palmieri V, et al. Central but not brachial blood pressure predicts cardiovascular events in an unselected geriatric population: the ICARe Dicomano Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2432‐2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang Y, Kollias G, Argyris AA, et al. Association of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction with 24‐h aortic ambulatory blood pressure: the SAFAR study. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29:442‐448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Protogerou AD, Argyris AA, Papaioannou TG, et al. Left‐ventricular hypertrophy is associated better with 24‐h aortic pressure than 24‐h brachial pressure in hypertensive patients: the SAFAR study. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1805‐1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dart AM, Cameron JD, Gatzka CD, et al. Similar effects of treatment on central and brachial blood pressures in older hypertensive subjects in the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Trial. Hypertension. 2007;49:1242‐1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marwick TH, Gillebert TC, Aurigemma G, et al. Recommendations on the use of echocardiography in adult hypertension: a report from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE). J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:727‐754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Bortel LM, Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, et al. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid‐femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens. 2012;30:445‐448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herbert A, Cruickshank JK, Laurent S, et al. Establishing reference values for central blood pressure and its amplification in a general healthy population and according to cardiovascular risk factors. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McEniery CM, Yasmin, Wallace S, Maki‐Petaja K, et al. Increased stroke volume and aortic stiffness contribute to isolated systolic hypertension in young adults. Hypertension. 2005;46:221‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McEniery CM, Yasmin, McDonnell B, et al. Central pressure: variability and impact of cardiovascular risk factors the Anglo‐Cardiff Collaborative Trial II. Hypertension. 2008;51:1476‐1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kollias A, Lagou S, Zeniodi ME, Boubouchairopoulou N, Stergiou GS. Association of central versus brachial blood pressure with target‐organ damage systematic review and meta‐analysis. Hypertension. 2016;67:183‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Safar ME, Blacher J, Pannier B, et al. Central pulse pressure and mortality in end‐stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2002;39:735‐738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mitchell GF, Hwang SJ, Vasan RS, et al. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;121:505‐511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mitchell GF, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, et al. Transfer function‐derived central pressure and cardiovascular disease events: the Framingham Heart Study. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1528‐1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Abdelmoneim SS, et al. A randomized pilot study of aortic waveform guided therapy in chronic heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sharman JE, Marwick TH, Gilroy D, et al. Randomized trial of guiding hypertension management using central aortic blood pressure compared with best‐practice care: principal findings of the BP GUIDE study. Hypertension. 2013;62:1138‐1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]