Abstract

Often considered to be a symptomless condition, hypertension can be associated with a significant emotional burden. To analyze changes of health‐related quality of life as well as the emotional burden questions regarding the impact of hypertension were incorporated into the noninterventional SeviTarget study. Comparisons were made between baseline and follow‐up findings, and between patients with treatment target achievement and those without. A total of 5831 patients were recruited. At baseline, only 33.3% of patients described their current state of health as good or excellent, while at follow‐up this value had risen to 75.8%. Responses regarding symptoms and limitations in activities and mental factors such as anxiety associated with treatment all improved during antihypertensive treatment. Changes to more optimistic responses were more likely for patients who achieved a target BP of <140/90 mm Hg. The study demonstrates that improvements in quality of life and the perceived emotional burden related to hypertension can be achieved with effective management of hypertension.

Keywords: blood pressure control, fixed‐dose combination therapy, hypertension, mental health, quality of life

1. Introduction

Hypertension is generally perceived as a disease without symptoms.1, 2 It appears, however, that the condition is associated with a high burden of nonspecific symptoms that are considerably increased among hypertensive patients in comparison to the general population. A number of studies that have documented a reduced quality of life in patients with uncontrolled hypertension confirm this observation.3, 4, 5

Several surveys have examined knowledge and attitudes among hypertensive patients.6, 7, 8 In one questionnaire study, it was found that patients with uncontrolled hypertension experienced a greater emotional impact from the condition than those for whom it was controlled.7 In a worldwide survey in 2649 patients with uncontrolled hypertension it was observed that approximately a third were concerned about their “health overall” and half of them were often “anxious about managing their blood pressure” and were “worried about their poor blood pressure control.”9 Thus, in addition to the classical analysis of quality of life, it is important to analyze the emotional state of patients, including their levels of stress and anxiety and symptoms related to their disease.

There is a clear necessity to not only assess the impact of antihypertensive treatment on blood pressure (BP), but also to evaluate its effect on hypertension‐related quality of life and mental health. Some preliminary research has shown improvements in mood and certain life satisfaction measures (health, physical condition, mental condition, mood, appearance, abilities, job situation, leisure time, and family life).3, 4, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 To explore these areas further, we incorporated a series of questions about patients’ perceptions regarding the impact of uncontrolled hypertension on their lives into a large study on the real‐world effectiveness of the fixed‐dose combination (FDC) of olmesartan, amlodipine, and hydrochlorothiazide.16 The study was carried out at multiple centers throughout Austria and Germany and demonstrated a high BP response rate to the FDC, with low occurrence of adverse drug reactions. The objective of the present research was to increase our understanding of the differences in patients′ perceptions of living with uncontrolled hypertension, in addition to the impact of antihypertensive treatment.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a binational, multicenter, noninterventional, open‐label, prospective, noncontrolled observational study carried out between November 2012 and December 2013. A total of 5831 patients were recruited from primary care centers in Austria and Germany.16 The protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committees in each country, and the study was performed according to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Signed informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment. The study was registered with the “Verband Forschender Arzneimittelhersteller” (http://www.vfa.de).

2.2. Patient population and schedule

Adult patients (≥18 years) with essential hypertension were eligible for inclusion, provided that the olmesartan/amlodipine/hydrochlorothiazide FDC tablet was indicated according to the summary of product characteristics, and treatment with the FDC had been initiated <2 weeks before the baseline visit. Exclusion criteria included contraindications to the FDC (eg, known hypersensitivity to any of the active substances, or to any excipients of the compound); impaired renal function; treatment‐resistant hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, or symptomatic hyperuricemia; severely impaired liver function; cholelithiasis or biliary tract obstruction; severe hypotension; (cardiogenic) shock; left ventricular obstruction; hemodynamically unstable heart failure after acute myocardial infarction; planned or existing treatment with the direct renin‐inhibitor aliskiren; and planned or current pregnancy.

2.3. Questionnaires

Patients were asked to complete the set of three questionnaires at study inclusion and at the final visit approximately 24 weeks later. All questionnaires were provided to patients in their native language (German). Office BP was recorded in duplicate after 5 minutes of rest with standardized approved devices.

The composition of questionnaires A and B (Tables S1 and S2) were based on a prior survey conducted in patients with uncontrolled or resistant hypertension.9 These questionnaires were developed by the Power Over Pressure Steering Committee of the American Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Hypertension, which consisted of physicians who were experts in the field of hypertension. These questionnaires aimed to address the anxiety and stress level caused by the condition “uncontrolled hypertension” (Table S1) and to capture severity and frequency of nonspecific symptoms associated with the condition (Table S2). These questionnaires have been applied in a worldwide study of 2649 patients with uncontrolled hypertension and 1925 patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension.9 Because of the complexity of these questionnaires we are referring to each question (eg, A2) in the text, which indicates questionnaire A, question 2.

The evaluation of questionnaire C (12‐Item Short‐Form [SF‐12] questionnaire) was performed according to published procedures17, 18 and in accordance with the handbook SF‐36 questionnaire for health status.19 This questionnaire has been used in parallel for comparison purposes with other similar ventures, because it is validated and has been used in a number of hypertension studies.

BP was considered to have normalized in cases where systolic BP was below 140 mm Hg and diastolic BP was below 90 mm Hg. BP response was defined as a reduction of 20 mm Hg systolic and/or 10 mm Hg diastolic.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Data were documented using a paper case report form and were entered into an electronic data capture system/project database. To allow for analysis, responses to the questions were binarized into positive and negative responses. Exploratory descriptive statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). To analyze whether the change in BP and its control influences anxiety and emotional stress levels as well as quality‐of‐life measures we calculated the odds ratio of each parameter (responders or nonresponders).

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 5831 patients were enrolled in the study, 451 from within Austria and 5380 from within Germany. The mean age of the patients was 63.5±11.8 years, and 47.0% were women (Table 1). The time since hypertension diagnosis was >5 years for 47.5% of patients, and <1 year for 11.1% of patients. A high proportion of patients had cardiovascular risk factors, with diabetes mellitus (29.4%) and the metabolic syndrome (21.1%) being the most prevalent. Only a few patients had experienced irreversible damage to their cardiovascular system, and cardiovascular morbidity was <10%. Within this population, questionnaires A and B were completed by 3439 patients, while the SF‐12 questionnaire was completed by 3437 patients. There was no clinically relevant difference between patients for which questionnaires were available and those without (data not shown).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics (N=5831)

| Mean±SD or % | |

| Age, mean±SD, y | 63.5±11.79 |

| Female sex, % | 47.0 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.4±4.89 |

| Essential hypertension | 97.9 |

| Time since diagnosis, % | |

| Unknown | 6.5 |

| <1 y | 11.1 |

| 1–5 y | 30.1 |

| >5 y | 47.5 |

| Risk factors, % | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29.4 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 21.1 |

| Smoking | 17.8 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 9.9 |

| Cardiac failure | 7.4 |

| Renal dysfunction | 4.3 |

| Stroke/TIA | 4.1 |

| Stable angina pectoris | 4.0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3.6 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3.5 |

| Hepatic impairment | 1.3 |

| Other unspecified risk factors | 24.3 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

3.2. Perceived strain of hypertension

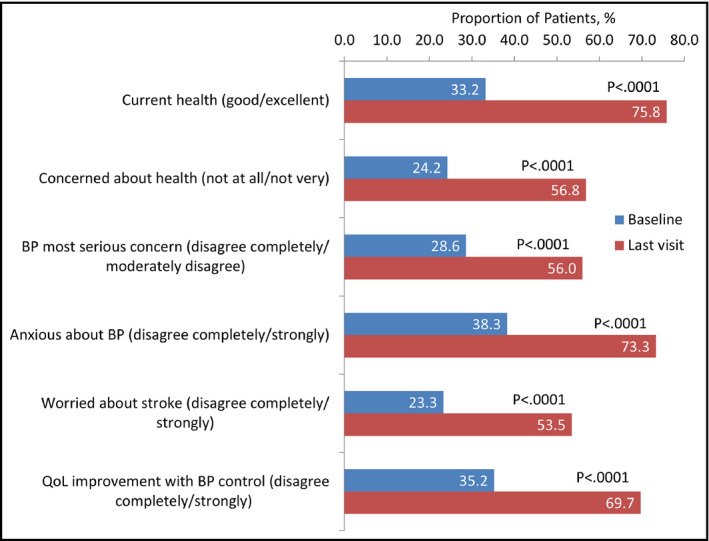

At baseline, only 33.2% of patients described their current state of health as good or excellent (A1), while at follow‐up this value had risen to 75.8% (Table 2 , Figure). A total of 24.2% patients were unconcerned or barely concerned about their health (A2) at baseline, and only 28.6% did not consider hypertension to be their most serious health concern (A3). At follow‐up, these values had approximately doubled, and it was seen that reaching the target BP of <140/90 mm Hg made it more likely that a patient would have become less concerned during the study (Tables 2, 3, 4). The proportions of patients reporting no or few negative effects of hypertension on aspects of daily life (A4) varied between 60% and 80% at baseline, with the effect on overall health being the most significant and relationships with friends being the least. At follow‐up, over 80% of patients reported no or few negative effects on each area of life.

Table 2.

Answers to Questionnaire A

| Percent at Baseline | Percent at Follow‐Up | P Valuea | Target BPb | BP Responsec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How would you describe your current health state? (good/excellent) | 33.2 | 75.8 | <.0001 | 1.13 (0.97–1.30) | 2.13 (1.55–2.91) |

| 2. How concerned are you currently about your health? (not at all/not very) | 24.2 | 56.8 | <.0001 | 1.24 (1.07–1.45) | 1.45 (1.06–1.98) |

| 3. Blood pressure is my most serious health concern (disagree completely/moderately disagree) | 28.6 | 56.0 | <.0001 | 1.22 (1.04–1.43) | 2.15 (1.49–3.10) |

| 4. Has blood pressure adversely affected the following areas of your life? (not at all/a little) | |||||

| 4.1 Relationship with my spouse | 76.0 | 88.6 | <.0001 | 1.21 (0.98–1.49) | 2.21 (1.29–3.78) |

| 4.2 Relationship with my family (other than spouse) | 77.6 | 91.0 | <.0001 | 1.10 (0.90–1.35) | 2.48 (1.43–4.31) |

| 4.3 Relationship with my friends | 79.8 | 92.0 | <.0001 | 1.20 (0.97–1.49) | 3.79 (1.93–7.44) |

| 4.4 Relationship with my colleagues | 75.4 | 85.6 | <.0001 | 1.07 (0.85–1.36) | 8.31 (2.64–26.16) |

| 4.5 My work place or my ability to work | 67.3 | 83.2 | <.0001 | 1.08 (0.89–1.32) | 2.58 (1.48–4.50) |

| 4.6 My hobbies | 72.6 | 89.0 | <.0001 | 1.16 (0.96–1.39) | 2.23 (1.39–3.56) |

| 4.7 My ability to carry out everyday household tasks | 69.6 | 88.0 | <.0001 | 1.01 (0.85–1.21) | 2.39 (1.51–3.78) |

| 4.8 My overall contentment | 61.9 | 86.5 | <.0001 | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 2.29 (1.54–3.39) |

| 4.9 My mood | 63.4 | 86.1 | <.0001 | 1.02 (0.86–1.20) | 2.02 (1.36–2.98) |

| 4.10 My sex life | 66.2 | 82.3 | <.0001 | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) | 3.16 (1.79–5.60) |

| 4.11 My overall health | 60.3 | 84.8 | <.0001 | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 2.38 (1.59–3.55) |

| 5. Which statements about the management of your high blood pressure apply? (disagree completely/moderately disagree) | |||||

| 5.1 I wish it was easier to control my blood pressure | 19.6 | 64.4 | <.0001 | 1.41 (1.21–1.63) | 2.40 (1.75–3.29) |

| 5.2 I am often anxious about the management of my blood pressure | 38.3 | 73.3 | <.0001 | 1.30 (1.12–1.51) | 3.03 (2.10–4.38) |

| 5.3 I feel helpless in the management of my blood pressure | 54.1 | 84.2 | <.0001 | 1.15 (0.98–1.34) | 3.46 (2.28–5.26) |

| 5.4 I wish there were more options for managing my blood pressure | 34.7 | 74.1 | <.0001 | 1.15 (0.99–1.34) | 2.33 (1.68–3.23) |

| 6. Which statements about the impact of high blood pressure on your life apply? (disagree completely/moderately disagree) | |||||

| 6.1 I am worried about having a stroke because of high blood pressure | 23.2 | 53.5 | <.0001 | 1.20 (1.03–1.40) | 2.19 (1.53–3.13) |

| 6.2 I cannot fully enjoy my life because of my high blood pressure | 46.6 | 77.0 | <.0001 | 1.21 (1.04–1.41) | 2.65 (1.81–3.87) |

| 6.3 My quality of life would greatly improve if I had my blood pressure under control | 35.2 | 69.7 | <.0001 | 1.20 (1.04–1.40) | 2.06 (1.48–2.88) |

| 6.4 I am worried that I will die prematurely because of my high blood pressure | 37.1 | 64.8 | <.0001 | 1.15 (0.98–1.34) | 2.01 (1.40–2.88) |

| 7. Which statements about your current antihypertensive medication apply? (disagree completely/moderately disagree) | |||||

| 7.1 The number of medications I take concerns me | 48.8 | 77.3 | <.0001 | 1.02 (0.87–1.19) | 1.37 (0.99–1.90) |

| 7.2 I wish I could take fewer pills to lower my blood pressure | 35.3 | 73.6 | <.0001 | 1.18 (1.02–1.37) | 1.72 (1.26–2.35) |

| 7.3 It is not easy to adhere to therapy due to the high number of antihypertensive pills and other medications I have to take | 52.2 | 82.0 | <.0001 | 1.01 (0.86–1.18) | 1.75 (1.24–2.46) |

aMcNemar test. bLikelihood of patients who achieved target blood pressure (BP) giving a more positive answer at follow‐up in comparison to baseline. cLikelihood of patients who showed a response giving a more positive answer at follow‐up in comparison to baseline.

Figure 1.

Emotional burden from “uncontrolled hypertension.” BP indicates blood pressure

Table 3.

Answers to Questionnaire B

| Percent at Baseline | Percent at Follow‐Up | P Valuea | Target BPb | BP Responsec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How frequently did you experience these issues or symptoms within the last 4 weeks (never/very rarely/rarely) | ||||||

| 1.1 Cold hands or feet | 64.4 | 81.7 | <.0001 | 1.07 (0.89–1.28) | 2.17 (1.38–3.41) | |

| 1.2 Tiredness | 38.4 | 65.6 | <.0001 | 1.11 (0.95–1.30) | 1.66 (1.18–2.35) | |

| 1.3 Irregular heart beat | 64.4 | 84.4 | <.0001 | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) | 1.78 (1.19–2.67) | |

| 1.4 Restlessness | 49.3 | 76.1 | <.0001 | 1.02 (0.87–1.19) | 1.65 (1.16–2.34) | |

| 1.5 Chest tightness | 71.6 | 89.2 | <.0001 | 0.91 (0.76–1.09) | 1.67 (1.10–2.53) | |

| 1.6 Head pressure | 56.9 | 84.3 | <.0001 | 0.93 (0.80–1.09) | 2.06 (1.42–2.97) | |

| 1.7 Fatigue | 45.1 | 71.6 | <.0001 | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) | 1.59 (1.12–2.25) | |

| 1.8 Headache | 52.8 | 80.2 | <.0001 | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | 2.71 (1.81–4.04) | |

| 1.9 Drowsiness | 77.7 | 90.6 | <.0001 | 0.92 (0.76–1.12) | 1.82 (1.13–2.95) | |

| 1.10 Shortness of breath | 69.9 | 85.5 | <.0001 | 0.84 (0.70–1.01) | 1.43 (0.95–2.15) | |

| 1.11 Sleep disturbances | 53.0 | 71.5 | <.0001 | 0.97 (0.81–1.15) | 1.80 (1.19–2.70) | |

| 1.12 Sweaty hands or feet | 80.9 | 91.1 | <.0001 | 0.96 (0.78–1.19) | 3.00 (1.58–5.71) | |

| 1.13 Dizziness | 64.4 | 84.0 | <.0001 | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | 2.07 (1.36–3.15) | |

| 1.14 Pounding heart | 67.8 | 87.4 | <.0001 | 0.84 (0.70–0.99) | 1.48 (1.01–2.19) | |

| 1.15 Swollen ankles | 73.6 | 86.9 | <.0001 | 0.86 (0.71‐1.04) | 1.38 (0.91–2.11) | |

| 2. How intensely did you feel these issues or symptoms within the last 4 weeks (did not feel it/very weakly/weakly) | ||||||

| 2.1 Cold hands or feet | 63.6 | 78.0 | <.0001 | 1.10 (0.91–1.33) | 1.79 (1.16–2.78) | |

| 2.2 Tiredness | 38.3 | 62.3 | <.0001 | 1.02 (0.87–1.21) | 1.58 (1.10–2.26) | |

| 2.3 Irregular heart beat | 65.0 | 80.8 | <.0001 | 0.92 (0.77–1.11) | 1.70 (1.11–2.59) | |

| 2.4 Restlessness | 50.5 | 72.6 | <.0001 | 1.07 (0.90–1.27) | 1.68 (1.15–2.43) | |

| 2.5 Chest tightness | 69.9 | 82.9 | <.0001 | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 1.75 (1.10–2.79) | |

| 2.6 Head pressure | 55.7 | 78.4 | <.0001 | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 2.22 (1.48–3.32) | |

| 2.7 Fatigue | 44.6 | 67.8 | <.0001 | 1.06 (0.90–1.25) | 1.94 (1.33–2.84) | |

| 2.8 Headache | 49.9 | 74.8 | <.0001 | 1.09 (0.93–1.29) | 2.25 (1.53–3.33) | |

| 2.9 Drowsiness | 74.6 | 84.0 | <.0001 | 0.95 (0.77–1.17) | 1.67 (1.01–2.74) | |

| 2.10 Shortness of breath | 67.2 | 79.6 | <.0001 | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 1.33 (0.87–2.02) | |

| 2.11 Sleep disturbances | 49.4 | 66.4 | <.0001 | 0.95 (0.80–1.13) | 1.63 (1.09–2.43) | |

| 2.12 Sweaty hands or feet | 78.1 | 85.5 | <.0001 | 1.06 (0.84–1.32) | 2.09 (1.18–3.71) | |

| 2.13 Dizziness | 63.4 | 79.0 | <.0001 | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 2.00 (1.28–3.12) | |

| 2.14 Pounding heart | 68.0 | 82.2 | <.0001 | 0.88 (0.73–1.06) | 2.16 (1.33–3.50) | |

| 2.15 Swollen ankles | 72.4 | 81.5 | <.0001 | 0.91 (0.74–1.11) | 1.58 (0.98–2.54) | |

aMcNemar test. bLikelihood of patients who achieved target blood pressure (BP) giving a more positive answer at follow‐up in comparison to baseline. cLikelihood of patients who showed a response giving a more positive answer at follow‐up in comparison to baseline.

Table 4.

Answers to Questionnaire C (SF‐12)

| Percent at Baseline | Percent at Follow‐Up | P Valuea | Target BPb | BP Responsec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Health in general (excellent/very good) | 8.5 | 26.8 | <.0001 | 2.00 (1.64–2.45) | 2.40 (1.51–3.84) |

| 2. Limitation of moderate activities (not at all) | 31.9 | 53.1 | <.0001 | 1.24 (1.05–1.47) | 2.11 (1.41–3.17) |

| 3. Limitation of climbing several flights of stairs due to health (not at all) | 25.6 | 44.9 | <.0001 | 1.31 (1.10–1.57) | 2.30 (1.48–3.57) |

| During the past 4 weeks did you have? | |||||

| 4. Problems with work or other regular activities (less accomplishment than patient would have liked) (No) | 33.9 | 60.5 | <.0001 | 1.29 (1.10–1.52) | 2.91 (1.94–4.36) |

| 5. Problems with work or other regular daily activities (with respect to limitation in kind of work or other activities) (No) | 43.6 | 66.3 | <.0001 | 1.18 (0.998–1.39) | 2.51 (1.66–3.79) |

| 6. Interference with social activities (including both work outside the home and housework) due to physical health or emotional problems with respect to less accomplishment than patient would have liked (No) | 46.6 | 68.6 | <.0001 | 1.25 (1.05–1.47) | 2.95 (1.90–4.58) |

| 7. Interference with social activities (including both work outside the home and housework) due to physical health or emotional problems with respect to less care than usual in work or other activities (No) | 50.4 | 72.7 | <.0001 | 1.14 (0.97–1.34) | 2.62 (1.72–3.98) |

| 8. Interference with normal work (including both work outside the home and housework) due to pain (not at all, little) | 59.0 | 74.4 | <.0001 | 1.02 (0.85–1.22) | 2.02 (1.31–3.11) |

| 9. A feeling of calm and peacefulness (always/mostly) | 53.5 | 75.6 | <.0001 | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) | 2.51 (1.65–3.82) |

| 10. A feeling of having lots of energy (always/mostly) | 32.8 | 57.0 | <.0001 | 1.20 (1.02–1.42) | 2.44 (1.62–3.66) |

| 11. A feeling of downheartedness (rarely/never) | 49.0 | 69.5 | <.0001 | 1.07 (0.91–1.27) | 2.19 (1.47–3.27) |

| 12. Interference with contact with other people (visits with friends, relatives, etc) due to health status or constitution (rarely/never) | 54.0 | 76.4 | <.0001 | 1.13 (0.96–1.34) | 1.98 (1.35–2.92) |

| SF‐12 Physical Health Summary Score | 43.41d | 48.22d | 1.03 (0.87–1.21) | 1.94 (1.34–2.81) | |

| SF‐12 Mental Health Summary Score | 45.45d | 50.07d | 1.20 (1.01–1.42) | 2.86 (1.84–4.45) | |

Abbreviation: SF‐12, 12‐Item Short‐Form. aMcNemar test. bLikelihood of patients who achieved target blood pressure (BP) giving a more positive answer at follow‐up in comparison to baseline. cLikelihood of patients who showed a response giving a more positive answer at follow‐up in comparison to baseline. dFor the mental and physical score, the mean is presented.

In terms of the effect of antihypertensive treatment (A5), only 19.6% of patients did not wish for easier control of the condition, potentially because they felt it was well controlled (A5.1). At follow‐up, the impression of being controlled had risen significantly to 64.4%, and patients who reached the target BP were more likely to be among those who no longer stated a desire for better control. High proportions of patients initially reported feeling anxious about their BP (A5.2) or helpless (A5.3) in controlling it, with these being greatly reduced at follow‐up. Patients who reported a reduction in anxiety by follow‐up were more likely to be those who achieved target BP levels (Table 2).

A high percentage of patients were initially worried about having a stroke or about premature death caused by hypertension (A6.1, A6.4). By follow‐up, these values were much lower but still high. Patients who achieved the target BP were more likely to have become less concerned about these factors; furthermore, they were more likely to feel positive about the effect of hypertension on enjoyment of life.

Approximately 50% of patients were concerned about the number of different medications that they were taking at baseline (A7), with only 35.3% not stating a wish to take fewer pills (A7.2). A total of 52.2% of patients reported no or little difficulty in adhering to therapy owing to many pills and medications (A7.3). Improvements in each of these factors were seen at follow‐up, with <20% of patients still finding it difficult to adhere to antihypertensive therapy.

For patients who responded to the treatment, there was a significantly higher chance that they would respond more favorably to all of the questions in questionnaire A at follow‐up in comparison to baseline (Table 2, 3, 4). Thus, overall perceived emotional burden of the disease was impressively high at baseline, clearly decreased after 24 weeks, with those who responded well to TDC experiencing the greatest benefit.

3.3. Frequency and intensity of nonspecific symptoms

The proportions of patients who reported that they never/very rarely/rarely experienced any of the symptoms listed in questionnaire B rose from baseline to follow‐up (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the odds ratio estimate between patients who did or did not achieve target BP in terms of the likelihood of the frequency of these events changing during the study, with the exception of dizziness. Similar results were found when the patients were asked about the intensity of the symptoms.

For the patients who showed any response to the therapy, there was a greater likelihood of them reporting a lower frequency and intensity of most of the symptoms. Reductions in shortness of breath and swollen ankles were not found to be different between these patients and those who did not demonstrate a response (Table 3).

3.4. Overall physical and mental health

Reports of excellent or very good overall health rose significantly during the study from 8.5% to 26.8% (Table 4). Patients who achieved target BP were much more likely to state an improvement in overall health. By follow‐up, fewer patients reported limitations of moderate activities (C2) or problems with work or other daily activities (C5). Smaller proportions of patients reported interference with social activities at the end of the study in comparison to baseline. The mean overall physical health score increased from 43.41 to 48.22 during the study. In terms of mental health, the proportions of patients who reported feeling calm and peaceful and having lots of energy all or most of the time increased from baseline to follow‐up. The mean mental health score was calculated to have increased from 45.45 to 50.07.

For patients who responded to the FDC treatment, both the physical and mental health aspects of the SF‐12 questionnaire were more likely to have improved during the study in comparison to the nonresponders (Table 4).

3.5. Patient subgroups

More men than women described their current health as excellent or good, both at baseline and at follow‐up (Table 5). Men were also less likely to be concerned about their health or consider hypertension to be their most serious health problem. A higher proportion of men scored above median in both the mental and physical SF‐12 scores.

Table 5.

Health Perception in Patient Subgroups (Disease Burden Set: n=3439; SF‐12 Set: n=3437)

| Percent at Baseline | Percent at Follow‐Up | |

|---|---|---|

| How would you describe your current health state (good/excellent) | ||

| Men | 36.3 | 79.2 |

| Women | 29.7 | 72.0 |

| Age <65 y | 37.4 | 81.4 |

| Age ≥65 y | 28.2 | 69.2 |

| With CVDa | 19.3 | 55.7 |

| Without CVDa | 35.4 | 79.0 |

| Diabetic disease | 24.2 | 64.6 |

| No diabetic disease | 37.1 | 80.6 |

| How concerned are you about your health (not at all/not much) | ||

| Men | 27.8 | 60.5 |

| Women | 20.1 | 52.7 |

| Age <65 y | 26.2 | 63.5 |

| Age ≥65 y | 21.8 | 48.9 |

| With CVDa | 14.8 | 37.3 |

| Without CVDa | 25.7 | 59.9 |

| Diabetic disease | 20.8 | 46.1 |

| No diabetic disease | 25.6 | 61.4 |

| Blood pressure most serious health concern (not at all/barely) | ||

| Men | 30.7 | 58.5 |

| Women | 26.2 | 53.1 |

| Age <65 y | 27.0 | 55.4 |

| Age ≥65 y | 30.5 | 56.7 |

| With CVDa | 29.3 | 54.0 |

| Without CVDa | 28.5 | 56.3 |

| Diabetic disease | 32.8 | 56.9 |

| No diabetic disease | 26.8 | 55.5 |

| SF‐12 Mental Health Summary Score | ||

| Men (above median at baseline) | 53.4 | 74.7 |

| Women (above median at baseline) | 42.6 | 65.8 |

| Age <65 y (above median at baseline) | 49.7 | 74.6 |

| Age ≥65 y (above median at baseline) | 46.7 | 65.7 |

| With CVDa (above median at baseline) | 39.0 | 59.7 |

| Without CVDa (above median at baseline) | 49.8 | 72.2 |

| Diabetic disease (above median at baseline) | 43.4 | 63.2 |

| No diabetic disease (above median at baseline) | 50.5 | 73.7 |

| SF‐12 Physical Health Summary Score | ||

| Men (above median at baseline) | 53.2 | 78.5 |

| Women (above median at baseline) | 43.0 | 67.5 |

| Age <65 y (above median at baseline) | 55.1 | 80.8 |

| Age ≥65 y (above median at baseline) | 40.6 | 64.5 |

| With CVDa (above median at baseline) | 26.2 | 53.9 |

| Without CVDa (above median at baseline) | 52.0 | 76.4 |

| Diabetic disease (above median at baseline) | 37.7 | 62.2 |

| No diabetic disease (above median at baseline) | 53.0 | 78.1 |

Cardiac failure, stroke/transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, renal dysfunction.

Patients younger than 65 years were more likely to describe their current health as excellent or good, with 81.4% of such patients stating this at follow‐up. This group were slightly more likely to be unconcerned about their health but more likely to consider hypertension to be their most serious condition. The proportion of patients younger than 65 years with mental health scores above median was a little higher than that of the patients 65 years and older; however, the score increased more significantly for the younger patients during the study. There was a greater difference in terms of the physical health score, with 55.1% of the younger group and 40.6% of the older group achieving scores above median at baseline. The proportions of patients reaching scores above median increased by similar amounts during the study.

Low numbers of patients with cardiovascular disease or diabetes described their current health as excellent or good at baseline, and while this improved during the study, values were still low in comparison to the overall study population. The majority of patients with these conditions were concerned about their health, while they were as likely to consider hypertension to be their most serious problem as patients without them. The proportions of patients with physical and mental health scores above median were significantly lower for the groups with cardiovascular disease or diabetes in comparison to the patients without these conditions.

4. Discussion

The general burden of the condition “uncontrolled hypertension” appeared quite high at baseline, with few patients describing their overall current health as excellent/good in questionnaire A or excellent/very good in the SF‐12 questionnaire. Men were found to be more likely to describe their health in these positive terms than women were, which is in agreement with other studies.20 At the follow‐up visit 24 weeks after initiation of FDC treatment, more patients considered their health to be good/excellent, with patients who achieved the target BP of <140/90 mm Hg being much more likely than those who failed to report better health at the end of the study in comparison to the start. This improvement correlates with the observed target BP achievement of 67.5% that we previously reported for this patient population, along with the low rate of adverse events during the 24‐week follow‐up period.16 This observation is in potential disagreement with prior work published by Trevisol and colleagues,20 which described an association between treated hypertension and reduced quality of life. This has been attributed to the awareness of the disease and adverse events related to the use of BP agents, but not the BP per se. Reasons for the discrepancy may include: (1) that we had no control group with untreated hypertension nor normotensive patients to compare with, and (2) we selected patients by the use of a particular drug combination that has been reported to have a low side‐effect profile. Therefore, we believe that, although there was no control group owing to the observational nature of the study, BP control is likely a major contributor to the perceived improvement in health.

At baseline, a high proportion of patients stated a desire for easier BP control and a reduction in the number of pills they had to take to control their condition. After 24 weeks of treatment with the FDC therapy, there was a significant decrease in the quantity of such patients. The requirement for fewer pills is known to be a major factor in increasing patient compliance with antihypertensive therapy.21, 22 Initiation of FDC treatment would therefore understandably result in greater satisfaction with the daily drug regimen. Patients who achieved the target BP of <140/90 mm Hg were found to be more likely to no longer state a desire for easier BP control by the end of the follow‐up period, they were also less likely to be anxious about managing hypertension.

While hypertension is generally not associated with any specific symptoms, a variety of issues such as fatigue, arrhythmia, and dizziness are often reported. When asked about the occurrence of certain symptoms during the 4 weeks prior to the study, high proportions of patients described having experienced such events more frequently than “rarely.” In particular, tiredness, fatigue, and restlessness were reported by over 50% of patients, with these same issues stated to be felt more than “weakly.” After the 24 weeks of FDC treatment, the occurrence of all symptoms, as well as their intensities, had decreased significantly. Again, this may be linked to the high rate of target BP achievement that was demonstrated during the study, although patients who reached the target were not found to be more likely to report a reduction in these symptoms in comparison to those who failed.16

The SF‐12 questionnaire was designed as a concise method by which to assess patients’ overall physical and mental health.17 While reported restrictions in physical and social activities in the present study could not solely be attributed to hypertension, the decreases that were evident after the 24 weeks of FDC therapy indicate that this condition made a significant contribution to these limitations. Both the physical and mental health summary scores were higher for the male population at baseline and follow‐up, and there were more men than women with a score above median. Such gender differences have been previously reported for studies regarding health‐related quality of life.20, 23, 24

Because of the observational nature of the study, no control groups could be analyzed. This prevents us from drawing definitive conclusions as to what extent the different aspects of the questionnaires were affected by the reduction in hypertension itself and by mere participation in a clinical study. However, the dependency of the parameters indicating emotional burden of the disease (anxiety and emotional stress level) from the BP response suggest that at least to some extent the improved levels of anxiety and emotional stress is caused by better BP control. The large population of patients that completed the questionnaires both at baseline and follow‐up also provides good statistical power in addition to enabling subgroup analysis.

5. Conclusions

The patients’ responses to the questionnaires clearly demonstrate improvements in many factors related to quality of life on being treated with the FDC therapy. Both physical and mental issues associated with hypertension improved during the 24 weeks of treatment. These improvements were likely due to the effective reduction in BP that was shown for a majority of patients, as well as the lower number of pills that the patients were required to take. The results therefore call for giving more attention to the effects of hypertension on hypertension‐related quality of life and mental health in clinical practice and to utilize the full potential of appropriate drug‐drug combinations to improve health‐related quality of life and mental health.

Conflicts of Interest

Peter Bramlage and Roland E. Schmieder have received research funds and consultancy honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo. Eva‐Maria Fronk and Ana‐Filipa Alexandre are employees of Daiichi Sankyo.

Authors’ Contributions

Peter Bramlage, Eva‐Maria Fronk, Ana‐Filipa Alexandre, and Roland E. Schmieder designed the study. Eva‐Maria Fronk was responsible for the statistical analyses. Peter Bramlage drafted the first version of the manuscript, and all authors revised the article for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

None.

Schmieder, R. E. , Jumar, A. , Fronk, E.‐M. , Alexandre, A.‐F. and Bramlage, P. (2016), Quality of life and emotional impact of a fixed‐dose combination of antihypertensive drugs in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 19:126–134. doi: 10.1111/jch.12936

Funding information

The study was funded and conducted by Daiichi Sankyo Europe GmbH, Munich, Germany.

References

- 1. Bramlage P, Thoenes M, Kirch W, Lenfant C. Clinical practice and recent recommendations in hypertension management–reporting a gap in a global survey of 1259 primary care physicians in 17 countries. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A, Rehman SU, Durkalski VL, Egan BM. Therapeutic inertia is an impediment to achieving the Healthy People 2010 blood pressure control goals. Hypertension. 2006;47:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmidt AC, Bramlage P, Limberg R, Kreutz R. Quality of life in hypertension management using olmesartan in primary care. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:1641–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bramlage P, Wolf WP, Fronk EM, et al. Improving quality of life in hypertension management using a fixed‐dose combination of olmesartan and amlodipine in primary care. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:2779–2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lambert GW, Hering D, Esler MD, et al. Health‐related quality of life after renal denervation in patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;60:1479–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oliveria SA, Chen RS, McCarthy BD, Davis CC, Hill MN. Hypertension knowledge, awareness, and attitudes in a hypertensive population. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller NH, Berra K, Long J. Hypertension 2008–awareness, understanding, and treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension in baby boomers and seniors: a survey conducted by Harris interactive on behalf of the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:328–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Egan BM, Lackland DT, Cutler NE. Awareness, knowledge, and attitudes of older americans about high blood pressure: implications for health care policy, education, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:681–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schmieder RE, Grassi G, Kjeldsen SE. Patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension report increased stress and anxiety: a worldwide study. J Hypertens. 2013;31:610–615; discussion 615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muller A, Montoya P, Schandry R, Hartl L. Changes in physical symptoms, blood pressure and quality of life over 30 days. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32:593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Y, Zhou Z, Gao J, et al. Health‐related quality of life and its influencing factors for patients with hypertension: evidence from the urban and rural areas of Shaanxi Province, China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carris NW, Ghushchyan V, Libby AM, Smith SM. Health‐related quality of life in persons with apparent treatment‐resistant hypertension on at least four antihypertensives. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30:191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cene CW, Halladay JR, Gizlice Z, et al. Associations between subjective social status and physical and mental health functioning among patients with hypertension. J Health Psychol. 2015. May 5. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marques da Silva P, Haag U, Guest JF, Brazier JE, Soro M. Health‐related quality of life impact of a triple combination of olmesartan medoxomil, amlodipine besylate and hydrochlorotiazide in subjects with hypertension. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Trevisol DJ, Moreira LB, Kerkhoff A, Fuchs SC, Fuchs FD. Health‐related quality of life and hypertension: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. J Hypertens. 2011;29:179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bramlage P, Fronk EM, Wolf WP, Smolnik R, Sutton G, Schmieder RE. Safety and effectiveness of a fixed‐dose combination of olmesartan, amlodipine, and hydrochlorothiazide in clinical practice. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2014;11:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pickard AS, Johnson JA, Penn A, Lau F, Noseworthy T. Replicability of SF‐36 summary scores by the SF‐12 in stroke patients. Stroke. 1999;30:1213–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand (SF36). Hogrefe Verlag. Available at www.qmetric.com [Google Scholar]

- 20. Trevisol DJ, Moreira LB, Fuchs FD, Fuchs SC. Health‐related quality of life is worse in individuals with hypertension under drug treatment: results of population‐based study. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neutel JM. The role of combination therapy in the management of hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1469–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sherrill B, Halpern M, Khan S, Zhang J, Panjabi S. Single‐pill vs free‐equivalent combination therapies for hypertension: a meta‐analysis of health care costs and adherence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:898–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Banegas JR, Lopez‐Garcia E, Graciani A, et al. Relationship between obesity, hypertension and diabetes, and health‐related quality of life among the elderly. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burstrom K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F. Swedish population health‐related quality of life results using the EQ‐5D. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:621–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials