1. WHAT IS THE LANCET COMMISSION?

Using the umbrella title “Lancet Commission,” the Lancet has created a series of comprehensive articles that examine the global burden of illnesses and healthcare issues presenting major threats to humanity on current and future generations. The latest in the series is on hypertension, and it is a magnificent document.1 The authors, advisors, and Lancet editorial team are to be congratulated for producing a vade mecum on hypertension that will serve as an invaluable resource for all interested in the management of the hypertensive crisis that is now recognized as the major contributory factor to cardiovascular disease, appropriately dubbed “the largest epidemic ever known to mankind.”2

But, one has to ask, who will read it? Certainly, only the most committed general practitioner will find time to give it even a cursory glance, and perhaps more importantly, our healthcare providers (whose reading ability is very limited) will not be up to coping with the voluminous recommendations of this document. All of which is a great pity because there are important evidence‐based recommendations for the present, and substantial policies of guidance for the future, in this document. Indeed, the Lancet should consider producing a summary document of its Commissions that would give them a deservedly wider readership. There is, admittedly, an executive summary, but apart from stating that “the Commission has identified ten accompanying mutually additive, and synergistic key actions that—if implemented effectively and broadly—will make substantial contributions to the management of blood pressure globally,” the “actions” are not readily accessible without immersing oneself in the entire document. I have done this, and I will make bold enough to summarize what seem to me to be its salient points in the hope that apart from bringing the document to attention, I may alert readers of the Journal of Clinical Hypertension to its recommendations, in the hope that some may be drawn to examine this valuable publication more closely. To summarize such a lengthy document (48 pages running to nearly 40 000 words) in the space allocated to me (3000 words) is a challenge that has forced me to concentrate on the essence of many recommendations that have a particular relevance to clinical practice, not only for practicing doctors, but for the wider readership that the Commission hopes to reach: “This report is not intended to be read exclusively by scientists and healthcare professionals but instead aims for a broader audience—including various industries, policy makers, and civil society.” Interestingly, and perhaps reassuringly, many of the recommendations in the Commission have been recently addressed in the columns of this journal, such as the deplorable control of blood pressure, the inaccuracy of devices, and the case for widespread use of ambulatory blood pressure measurement (ABPM) in primary care and the establishment of ABPM registries.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

2. WHAT IS HYPERTENSION?

The Commission sets out to justify blood pressure as a marker and the following iconoclastic statement should at least make us think and perhaps reappraise some concepts: “In hypertension, blood pressure is an almost ideal biomarker. Blood pressure is causally related to the development of the condition, defines the condition, predicts the outcome, is the target of therapeutic interventions, and serves as a surrogate marker to assess the benefit of therapies. Therefore, the role that other biomarkers could have in hypertension requires careful thought.” One might add that unfortunately blood pressure measurement as performed in practice, often with inaccurate devices, can be so misleading that it loses all diagnostic value.

The Commission is conservative in defining hypertension: “Initiation of treatment is dictated by an individual's risk profile and set of comorbidities (ie, assessed cardiovascular risk) and the level of blood pressure above which there is clear evidence that treatment will improve prognosis. Generally—particularly if the cardiovascular risk of the individual is unknown—this threshold will be the traditional cutoff values of 140 mm Hg systolic, 90 mm Hg diastolic, or both.” This traditional definition leaves much to be desired, but then things improve: “People with normal or high‐normal office blood pressure together with organ damage or at high cardiovascular risk should be offered home or ambulatory blood‐pressure monitoring, to exclude masked hypertension.” Indeed, the Commission, in keeping with recent guidelines, goes on in many places in the document to endorse out‐of‐office blood pressure, especially ABPM, for the diagnosis and management of hypertension.

3. THE MAGNITUDE OF THE GLOBAL EPIDEMIC

The Commission summarizes the global epidemic in succinct terms: “Elevated blood pressure is globally the strongest modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease and related disability. Its prevalence and downstream detrimental impact on health are increasing because of longer life expectancy and increased exposure to risk in the population.” In other words, if governments are to invest in disease prevention, and to aspire towards creating a healthy society, the best value for money would be the achievement of blood pressure control.

The global figures are awful, and as with all disasters, the public (and I include doctors in this category) eventually becomes exhausted by the sheer magnitude of the problem and turns its attention elsewhere. Painful though the demographic reality may be, it is nonetheless timely to be updated on the latest statistics in different parts of the world. Generally speaking, “approximately one in four adults have hypertension (when defined as blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic) and by 2025, hypertension is projected to affect more than 1.5 billion people worldwide. The estimated number of blood‐pressure‐related deaths yearly has increased by 49% to 10.4 million. In recent decades, there has been an epidemiological shift in the main cause of global disease burden from communicable to non‐communicable disease, with hypertension being the leading risk factor.” The Commission reminds us that if we live long enough, hypertension is an inevitable consequence of aging: “The pipeline of future patients includes virtually every human being. Even those who reach middle‐age without hypertension have a more than 90% chance of developing the condition during their remaining lifetime.”

Here, in affluent Europe there is no room for complacency: “The number of Europeans older than 65 years is predicted to double during the next 50 years to about 150 million, and in roughly the same period people older than 90 years are expected to constitute roughly 12% of elderly people in Europe (up from 0.5% of the US population in 2000), increasing the prevalence of hypertension. Cardiovascular diseases are projected to increase by a quarter in the next 30 years, and the number of cases among those aged 75 to 84 years is estimated to double in the same period.”

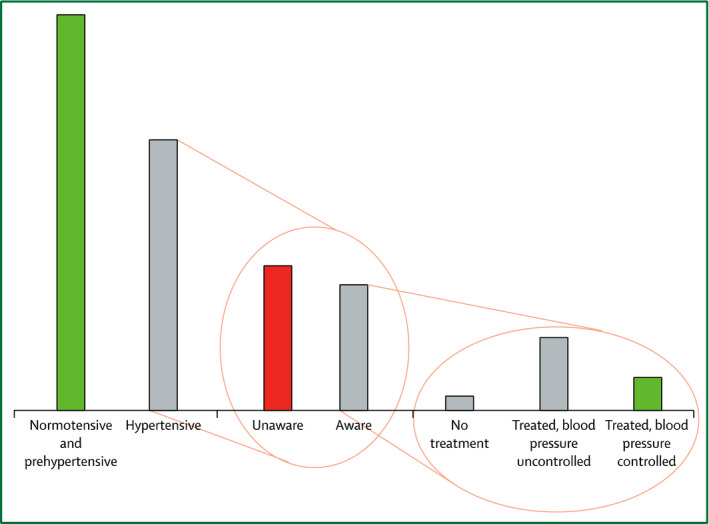

The Commission is not alone in joining a global chorus that states the enormity of the problem, but global action has been impotent, at least until now, to tackle a paradox that has bedevilled the management of hypertension: “Despite clear evidence for the benefits of blood pressure reduction using low‐cost and safe drugs, most individuals with hypertension in the world are undetected, untreated, or poorly controlled” (Figure). The pertinent questions to be answered are: “why is detection so low, why is control suboptimal, and how can these factors be improved? The answers must be found through focused research.” One of the more interesting conclusions of the Commission is: “Epidemiologically there is a strong dose‐response association between blood pressure and cardiovascular mortality that persists to 115/75 mm Hg. Thus, a substantial residual cardiovascular risk is present even in individuals with controlled hypertension.”

Figure 1.

Awareness of hypertension status. In the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study, most (53.5%) individuals with hypertension were unaware of their hypertensive status, and only 13% had well‐controlled blood pressure. Reprinted from Olsen et al.1

4. MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT

The Commission deals in debt with the traditional approaches to the management of hypertension, ie, lifestyle modification, blood pressure–lowering drugs, adherence to treatment, interventional procedures (eg, renal denervation—not recommended), and the treatment of comorbid diseases, such as diabetes. Although there may be little that is new in these categories, the evidence for and against different strategies is nicely updated. A few conclusions are worth noting.

4.1. Lifestyle

Having examined all the evidence, the Commission is refreshingly honest in acknowledging that despite the potential benefits of lifestyle modification, the results are overwhelmingly disappointing. “Substantial evidence supports the effectiveness of specific health behaviors to improve blood pressure, cardiovascular morbidity, and mortality. In terms of dietary intake, extensive evidence supports the beneficial effects of the Mediterranean diet (with extra virgin olive oil or nuts) and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, as well as a reduction in salt intake and increased potassium intake. Significant blood‐pressure‐lowering effects have been shown for dietary nitrate (found in beetroot juice and green leafy vegetables). Convincing evidence also supports cardiovascular protection by physical activity and improved fitness, weight loss, tobacco cessation, moderate to limited alcohol intake, and management of psychosocial stress.” But, the results of lifestyle modification over the past 50 years have been disappointing. “Lifestyle modification offers universal appeal as an intervention because the costs, in motivated individuals, are minimal and can lead to drug step‐down or withdrawal. However, in the absence of self‐motivation, achievement‐sustained lifestyle modifications require substantial resources over a longer period. Furthermore, although the benefits of lifestyle modification in cardiovascular prevention are clear, evidence to guide the use of individual‐based lifestyle modification as a stand‐alone or add‐on therapeutic intervention is lacking, which is perhaps most evident for dietary modifications.” Worthy aspirations to be sure but again the evidence is negative: “In one study, only 55% of young adults with hypertension had documented evidence of lifestyle education after diagnosis.”

4.2. Drug treatment

The Commission reiterates a well‐known dictum: “Most patients with hypertension require more than one drug to control their blood pressure. Despite blood pressure measurements in more than 150 national population‐based surveys in 97 countries, no fully reliable global or regional estimates of hypertension treatment coverage exist. In most of these surveys, at least half of adults with raised blood pressure had not been diagnosed with hypertension. Treatment coverage is therefore low, ranging from 7% to 61% among people who had presented with raised blood pressure in the household surveys.” However, it goes on to make a recommendation for the use of single‐pill combinations to overcome the well‐documented problem of therapeutic inertia: “Single‐pill combinations of two or more antihypertensive drugs … have the potential to reduce the number of tablets that patients have to take … and generally lead to improved blood‐pressure control,” and “where resources allow, single‐pill combination therapy should be available.” A last and very important recommendation; the Commission believes that patients should be made aware (empowered) of the success, or failure, of drug treatment by being shown the evidence for increasing, or decreasing, drug dosage and the most effective way of doing this is by showing the patient a plot of the ABPM measurement.8 “The Commission is convinced that it is very important for treatment adherence that the patient can see a clear relationship between increase in antihypertensive treatment and decrease in blood pressure. Therefore, we recommend use of either ambulatory, home, or automated unobserved blood pressure to initiate and titrate treatment (rather than the highly variable office blood pressure, which could mask the effectiveness of a drug).”

4.3. The elderly

Correctly, the Commission singles out the elderly as being deserving of especial mention. We are reminded that stroke is not the only cerebral consequence of hypertension: “Elevated blood‐pressure levels in middle‐age have been associated with increased risk of dementia in older age.” We are also reminded that elderly patients are particularly prone to the consequences of overtreatment: “More than 30% of people older than 65 years fall at least once annually, and antihypertensive treatment is a major (and modifiable) risk factor for falls.” In keeping with the lifecourse mandate of the Commission we are reminded that the prevention of functional impairment at older ages is important: “In individuals older than 75 years, in whom multiple diseases (primarily cardiovascular) coexist, a lifecourse approach will be aimed at preservation of functional reserve, slowing disease progression, and mitigating complications to optimise quality of life, with the potential to decrease the demand on the healthcare system.”

5. COULD TECHNOLOGY BE THE SOLUTION?

The Commission rightly, in my view, gives authoritative examination to the potential for technology to improve the global management of hypertension. Connected health solutions abound, and “more than 3 billion people worldwide are active internet users, with about 70% maintaining social media accounts,” but we need to identify the priorities in what might be called the “age of measurement.” We need to begin with blood pressure–measuring devices, which are notoriously inaccurate. We must recognize the truth in the empirical maxim that if “we can't measure it we can't diagnose or treat it.” The Commission acknowledges that: “Measurement devices for blood pressure have never been so available and affordable, but many might not be validated according to scientific standards.” The Medaval website has documented that from 1811 blood pressure–measuring devices on the market, only 184 have been validated for accuracy according to one of the international protocols.9 The Commission goes on to endorse the need for basic device accuracy: “Ideally, devices should comply with the validity guidelines of scientific societies, rather than just internal testing by the manufacturer, and this information should be clearly available for the customer. Professional societies could also give consideration to providing a seal of approval or certification of blood pressure devices meeting appropriate accuracy standards, which is particularly important given the rapid developments in wearable technologies marketed without validation testing according to current international expectations. Active warnings on sub‐standard devices can be provided.…The seal of approval could, in turn, be used by manufacturers for marketing.” The Commission urges “a close collaboration between a wide range of stakeholders such as governments, the mobile communications industry, health‐care professionals, the pharmaceutical industry, and professional societies to not only develop and distribute inexpensive, validated, and certified blood pressure monitors, but also to ensure correct use through simple mobile apps and online education endorsed by the professional societies.”

The Commission spent much time examining how patient involvement (awareness and empowerment are other terms used interchangeably) might be implemented as a means of improving global management of hypertension. “Awareness should be emphasised throughout, including equal basic access to validated blood pressure monitors in low‐income and middle‐income countries.”

6. THE ROLE OF REGISTRIES

The value of registries in helping to organize and focus healthcare delivery in many illnesses is now well recognized. Oddly, with the exception of Spain, hypertension registries have not been used effectively across the globe.10 The Commission asks for this state of affairs to be redressed: “The Commission encourages establishment of international collaborations to combine existing population surveys and create large web‐based registries—using cloud computing technology—based on data generated by patients’ use of widely available, easy to use, certified apps.”

7. ESSENTIAL GOALS AND RELATED KEY ACTION

So, at the end of all this, where are we? At the very least we have a sound, carefully researched, evidence‐based document that is basically a blueprint for society—a blueprint that warns of the impending consequences of carrying on as we are doing, and failing to act in a coordinated and purposeful way. However, the Lancet Commission report is only the first step in the implementation of 10 essential goals that are discussed at length in the text of the report and summarized in the Table. It is up to all of us to assist in bringing these laudable objectives to fulfillment.

Table 1.

Summary of Main Problems and Key Actions

| Key Actions | Keywords | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention: lifestyle and environmental changes | |||

| Unhealthy environment | Strategies and policies to accelerate socioeconomic improvements and development of health‐promoting environments; accelerate the implementation of accepted health‐promoting policies | Make healthy food choices easier, combat tobacco, and promote physical activity in daily living | Health‐promoting environment |

| Lack of understanding about unhealthy lifestyle | Early and sustained education about healthy lifestyles and blood pressure (new technology) | Educate and empower health workers and teachers to instill healthy lifestyles | Healthy behaviors |

| Low awareness | Ensure universal access to blood pressure measurement through inexpensive monitors and surveillance | Tailored education about hypertension throughout the lifecourse | Measurement access |

| Diagnosis and evaluation | |||

| Poor measurements | Certification and validation of monitors and endorsement of protocols for measuring blood pressure by professional societies | Develop simple, inexpensive blood pressure monitors; preference for home, ambulatory, automated, and unobserved blood pressure measurement | Measurement quality |

| Poor cardiovascular risk assessment | Promote education of patients, doctors, and health professionals | Reinforce targeting of global cardiovascular risk rather than single risk factors | Empowerment |

| Poor or delayed diagnosis of secondary hypertension | Simple protocols for detecting secondary hypertension in communities with few resources | Improve the availability of relevant investigations | Secondary hypertension |

| Pharmacological prevention and treatment | |||

| Lack of available healthcare professionals | Expand the capacity of the clinical workforce through task sharing and the use of endorsed education of community health workers | Health system collects, monitors, and responds appropriately to blood pressure levels (accountability) | Workforce expansion |

| Lack of good‐quality and effective antihypertensive drugs | Universal availability of at least one of each class of antihypertensive drug | Availability of single‐pill combinations where resources permit | Medication access |

| Lack of stratified treatment | Information about optimization of blood pressure targets, treatment initiation, and therapy based on ethnicity, age, and risk | Support randomized controlled trials that focus on optimization of treatment targets, initiation, and choice taking into account ethnicity, age, and risk | Standardized treatment |

| Blood pressure and healthcare systems | |||

| Promote and ensure capacity and accountability of the health system to conduct surveillance and monitoring | Promote and ensure accountability of the health system to respond appropriately to blood pressure levels | Health‐system strengthening | |

Modified from Olsen et al.1

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author reports no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Olsen MH, Angell SY, Asma S, et al. A call to action and a lifecourse strategy to address the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations: the Lancet Commission on hypertension. Lancet. 2016;388:2665‐2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yusuf S, Wood D, Ralston J, Reddy KS. The World Heart Federation's vision for worldwide cardiovascular disease prevention. Lancet. 2015;386:399‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Brien E. First Thomas Pickering memorial lecture: ambulatory blood pressure measurement is essential for the management of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14:836‐47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campbell NR, Berbari AE, Cloutier L, et al. Policy statement of the World Hypertension League on noninvasive blood pressure measurement devices and blood pressure measurement in the clinical or community setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:320‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Brien E, Dolan E, Atkins N. Failure to provide ABPM to all hypertensive patients amounts to medical ineptitude. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015;17:462‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Brien E. Why is it so difficult to influence the clinical management of hypertension? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:606‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dolan E, O'Brien E. How should ambulatory blood pressure measurement be used in general practice? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:218‐220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Brien E. If I had resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:e3‐e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Medaval website. http://medaval.ie/product-category/blood-pressure-monitors/. Accessed January 8, 2017.

- 10. O'Brien E. How registries can guide our future? Hypertension 2017;69:198‐199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]