Abstract

The prevalence of an exaggerated exercise blood pressure (BP) response is unknown in patients with subacute stroke, and it is not known whether an aerobic exercise program modulates this response. The authors randomized 53 patients (27 women) with subacute stroke to 12 weeks of twice‐weekly aerobic exercise (n = 29) or to usual care without scheduled physical exercise (n = 24). At baseline, 66% of the patients exhibited an exaggerated exercise BP response (peak systolic BP ≥210 mm Hg in men and ≥190 mm Hg in women) during a symptom‐limited ergometer exercise test. At follow‐up, patients who had been randomized to the exercise program achieved higher peak work rate, but peak systolic BP remained unaltered. Among patients with a recent stroke, it was common to have an exaggerated systolic BP response during exercise. This response was not altered by participation in a 12‐week program of aerobic exercise.

Keywords: exercise/hypertension, lifestyle modification/hypertension, stroke, stroke prevention

1. INTRODUCTION

Endurance exercise reduces resting and ambulatory blood pressure (BP) levels1 and is an important part of rehabilitation and secondary prevention after an acute stroke.2 However, patients in the early subacute phase after stroke have been shown to have a more significant rise in systolic BP (SBP) during exercise than age‐matched healthy controls.3 In patients without a history of previous cerebrovascular diseases, such an exaggerated BP response during exercise may be a risk factor for stroke.4 Some data suggest that after participation in a physical exercise program, peak SBP may increase in elderly patients5 or in patients with a recent transient ischemic attack.6 Despite this, only few studies7, 8 have reported how high BP actually rises during exercise in patients shortly after a stroke. Furthermore, it is not known whether participation in an aerobic exercise program modulates the peak BP reached during an exercise stress test in these patients. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to explore baseline data concerning peak SBP levels attained during a symptom‐limited ergometer exercise test in a group of patients in the subacute phase after stroke. The secondary aim was to evaluate the impact of 12 weeks of twice‐weekly intensive aerobic exercise on the SBP response to exercise in these patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patients and study design

We analyzed data from a single‐center clinical trial in which 56 patients with a recent stroke were randomized to either participation in a twice‐weekly intensive aerobic exercise program for 12 weeks (intervention group, n = 29) or to usual care (nonintervention group, n = 27). The study protocol (Clinical Trial Registration No: NCT02107768) was guided by the Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials statement, and has been previously described in detail.9 In brief, patients were recruited from the stroke unit at Vrinnevi Hospital, Norrköping, Sweden, during 2011 to 2013. Inclusion criteria were physician‐diagnosed stroke within the previous 3 days, medically stable as judged by the treating physician, age 50 years or older, ability to walk more than 5 meters with or without support, and ability to understand spoken and written instructions. Their impairments corresponded to mild stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale < 6) and thus their neurological impairment did not impair their ability to perform the ergometer exercise test. Exclusion criteria were medical or neurological diseases that could either constitute a risk or make the training program difficult to fulfill. This judgement was made by the treating physician. All patients, regardless of randomization outcome, performed a symptom‐limited, graded ergometer exercise test twice: prior to randomization (baseline, at a median of 22 days following the acute stroke) and after 12 weeks. Among the 56 patients who completed the main trial, peak BP data from the ergometer exercise tests were unavailable in three patients either at baseline, after 12 weeks, or both. Thus, complete ergometer BP data were obtained for 53 participants both at baseline and after 12 weeks. These 53 patients constitute the study population for the present analysis. Randomization was performed by shuffling concealed envelopes that were then picked randomly. Patients were included within 3 days of acute stroke diagnosis. Walking and balance tests were made within a median of 6 days following the acute stroke. However, because of logistical reasons, baseline ergometer exercise tests were not performed immediately, but with a median delay of 22 days. No intervention began prior to the baseline ergometer exercise test.

2.2. Ergometer exercise test

All ergometer exercise tests were performed at the department of Clinical Physiology at Vrinnevi Hospital, Norrköping, Sweden, by personnel who were unaware of to which group patients had been randomized. BPs were measured in the nonaffected arm. Resting diastolic BP and SBP were measured manually with the patient in the supine position after the patient had been resting during an ECG recording, and resting heart rate was recorded simultaneously. Repeated SBPs were measured manually throughout the ergometer exercise test. Since this was a trial that included patients with established vascular disease, including elderly and potentially frail participants, the exercise test protocol was adjusted individually. Initial work rate ranged between 20 and 50 W and increased progressively by 10 to 20 W per minute, as deemed appropriate by the responsible physician who supervised the exercise test. The same initial work rate that was used at the baseline test was also used at the test after 12 weeks. Cycling was performed with a target cadence of 60 revolutions per minute. The test was terminated when the patient reached volitional exhaustion or when conventional safety criteria for test termination occurred. Prespecified criteria for test termination included the following: chest pain, significant ST‐segment depression or elevation, ventricular tachycardia, atrioventricular block grade II or III, clinically significant decrease in heart rate, supraventricular tachycardia with heart rate > 200 beats per minute, SBP ≥ 280 mm Hg or SBP drop ≥ 15 mm Hg at one reading or ≥ 10 mm Hg at repeated readings. The test could also be terminated on other nonprespecified clinical grounds according to the judgement of the responsible physician who supervised the test. The results of the ergometer exercise tests were provided to the physician responsible for admitting the patients from the stroke ward, and patients were offered follow‐up, if deemed necessary, outside of the study protocol according to local practice guidelines.

2.3. Intervention

The aerobic exercise program that constituted the intervention consisted of a 12‐week training period that included 2 weekly 60‐minute aerobic exercise sessions, led by experienced physiotherapists (K.S. and M.K.) specialized in stroke rehabilitation.9 The program was designed in accordance with the recommendations for physical activity and exercise in stroke survivors issued by the American Heart Association.2 Each exercise session had 5 parts: a 15‐minute warmup (phase one), an 8‐minute aerobic part on an ergometer cycle (phase two), a 10‐minute part with low‐intensity mixed exercises (phase 3), another 8‐minute aerobic part on an ergometer cycle (phase 4), and a final 15‐minute cooldown (phase 5). The nonintervention group only received general advice about physical exercise and activity, but no specific exercise program was scheduled, since at the time of this study, patients with mild stroke were usually discharged to independent living without further structured rehabilitation (standard treatment as in usual care). No specific neuromotor therapy was given, neither in the intervention nor in the nonintervention group, since their impairments corresponded to mild stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale <6) according to the inclusion criteria and thus their neurological impairment did not warrant specific neuromotor therapy. All patients had a medical follow‐up visit by their physician 3 months after discharge, regardless of randomization outcome.

2.4. Intervention goals

The intensity of the exercise program was individualized. Each patient was given two fitness goals for each exercise session. First, during parts one, three, and five, the goal was to reach a light to moderate training level (self‐reported scores of 11–14 on the Borg rating of perceived exertion scale,10 corresponding to 50% of the estimated maximum oxygen uptake and 60% of the maximum heart rate). Second, during parts two and four of the exercise program, the goal was to reach an exertion level (self‐reported scores of 14–15 on the Borg rating of perceived exertion scale,10 corresponding to 75% of the estimated maximum oxygen uptake and 80% of the maximum heart rate.) The individual exercise intensity was adapted during each session by adjusting the load or the cycling speed so that the exercise goals were achieved. If the patients did not spontaneously reach the target intensity, they were given verbal encouragement. During exercise weeks 1, 6, and 9, the participants also carried polar HR80 monitors (Polar Electro OY) to help them achieve an exercise intensity that was within the prescribed target heart rate range. The monitors also made the participants aware of the degree of effort that was required to reach the target range.

2.5. Outcome variables

The difference between the peak SBP and the resting SBP (Δ SBP) was calculated for each patient both at baseline and at 12 weeks, as were the differences between the peak heart rate and the resting heart rate (Δ heart rate). Although no formal consensus exists concerning the cutoff level that defines a pathological BP response to exercise, we defined an exaggerated BP response as a rise of SBP to ≥210 mm Hg in men and a rise of SBP to ≥190 mm Hg in women, which is in line with commonly applied criteria.11, 12

2.6. Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation was based on the most important primary outcome measure of the previous publication,9 the 6‐minute walk test. Using a two‐tailed test with a type I error of 0.05 and a power of 80%, a clinically significant difference13 between the intervention and control group (improvement of 50 m [standard deviation, 53 m] for the 6‐minute walk test would be detected with a minimum sample of 20 patients per group). Considering possible dropouts, the primary study goal was to include at least 25 patients per group. For the statistical analyses, SPSS software (IBM) was used. Two‐sided P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Values are presented as means ± standard deviations or number of cases (percentages). For baseline data, between‐group differences were tested for statistical significance with two‐sided independent t tests for numerical variables or chi‐square test for categorical variables. For differences between variables measured at baseline and at 12 weeks, paired t tests were used for numerical variables and McNemar test was used for categorical variables. Strengths of correlations between numerical variables were tested with bivariate correlation analyses and presented as Pearson correlation coefficients (r) with their corresponding P values.

2.7. Ethics

All participants provided informed consent. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Linköping, Sweden, 2010.

3. RESULTS

3.1. BP response during ergometer exercise test at baseline

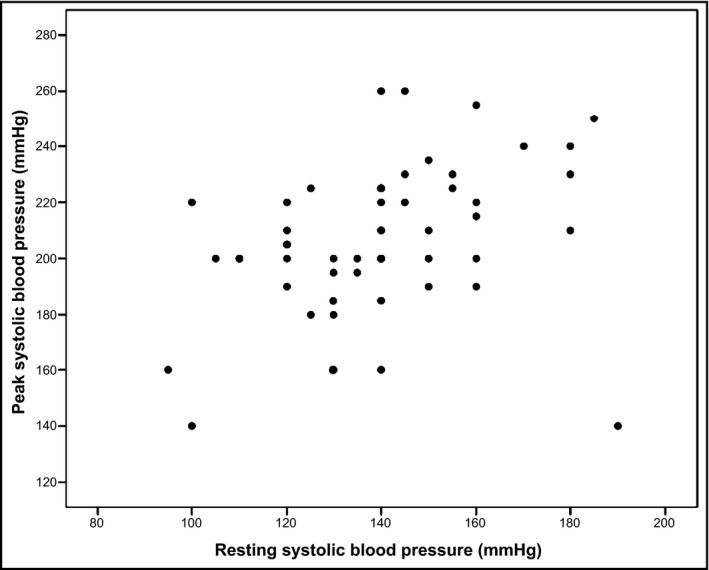

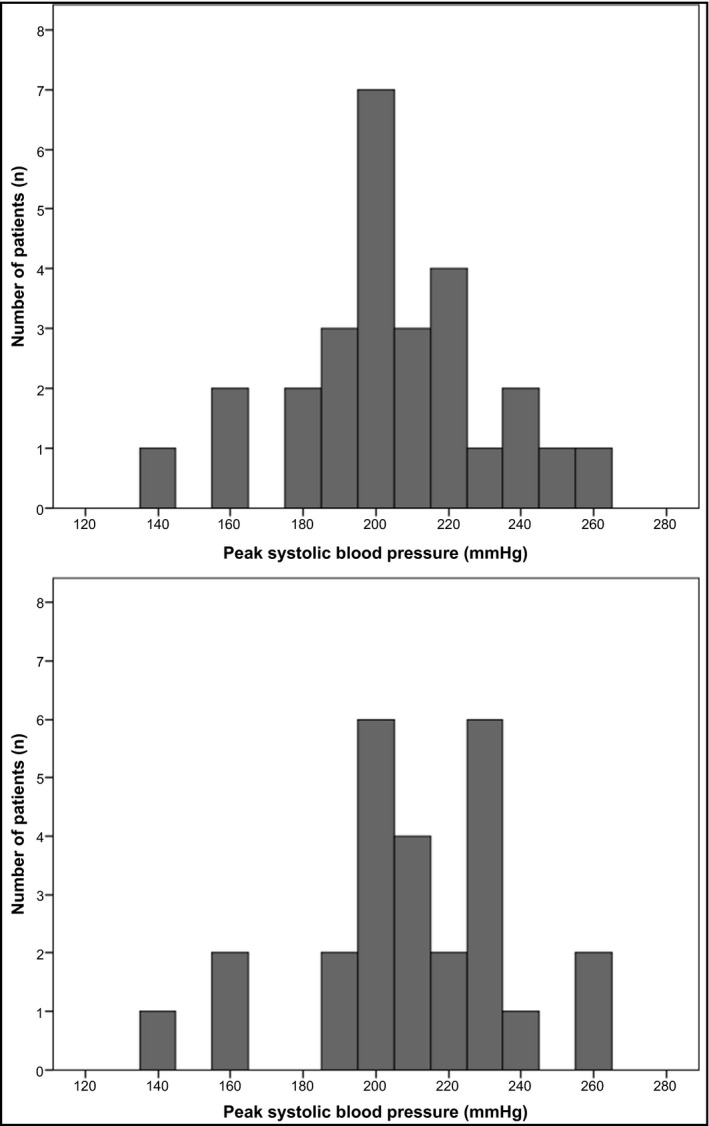

As shown in Table 1, resting BP was, on average, well controlled at baseline (mean resting BP 139.8 ± 21.8/77.6 ± 10.2 mm Hg), but the overall prevalence of an exaggerated BP response was 35/53 (66%). An exaggerated BP response occurred more frequently in patients with resting SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg, which is the conventional cutoff for hypertension,12 than in patients with resting SBP < 140 mm Hg (24/31 or 77.4% vs 11/22 or 50.0%, P = .038 [not in table]). Resting SBP was numerically higher among patients with an exaggerated BP response than among patients with a normal BP response, but the difference was not statistically significant (143.7 ± 21.3 mm Hg vs 132.2 ± 21.6 mm Hg, P = .070). Resting diastolic BP and resting heart rate did not differ significantly between patients with an exaggerated BP response and patients with a normal BP response (78.4 ± 10.8 mm Hg vs 75.9 ± 8.7 mm Hg [P = .402] and 81.9 ± 11.1 beats per minute vs 75.9 ± 14.6 beats per minute [P = .103]). There was a significant correlation between resting SBP and peak SBP (Figure 1). The proportion of patients with an exaggerated BP response did not differ significantly between women and men (20/27 or 74.1% vs 15/26 or 57.7%, P = .208) nor did mean peak SBPs (202.6 ± 26.7 mm Hg vs 209.4 ± 27.8 mm Hg, P = .366). The distributions of peak SBPs at baseline, stratified by sex, are illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and hemodynamic variables before and during a symptom‐limited ergometer exercise test in 53 patients in the subacute phase after a stroke

| Range | ||

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 27 (50.9) | — |

| Age, y | 70.9 ± 7.6 | 53–87 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.6 ± 3.8 | 19.8–36.4 |

| Diagnosed hypertension | 37 (69.8) | — |

| Diagnosed diabetes mellitus | 9 (17.0) | — |

| Type of stroke | ||

| Ischemic (includes cardioembolic) | 52 (98.1) | — |

| Hemorrhagic | 1 (1.9) | — |

| Stroke localization | ||

| Right hemisphere | 21 (39.6) | — |

| Left hemisphere | 28 (52.8) | — |

| Brainstem/cerebellum | 4 (7.5) | — |

| Use of walking aid | 7 (13.2) | — |

| 6‐min walking test, m | 393 ± 115.1 | 120–555 |

| Resting DBP, mm Hg | 77.6 ± 10.2 | 60–105 |

| Resting SBP, mm Hg | 139.8 ± 21.8 | 95–190 |

| Peak SBP, mm Hg | 205.9 ± 27.2 | 140–260 |

| Δ SBP, mm Hg | 66.1 ± 28.2 | −50 to 120 |

| Resting heart rate, bpm | 79.8 ± 12.6 | 58–115 |

| Peak heart rate, bpm | 139.4 ± 19.4 | 92–193 |

| Δ Heart rate, bpm | 59.6 ± 18.3 | 17–110 |

| Aerobic capacity, peak WR, W | 117.8 ± 32.6 | 55–198 |

| Exaggerated SBP responsea | 35 (66.0) | — |

Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations [range] or number (percentage).

Defined as peak systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥210 mm Hg in men or ≥190 mm Hg in women.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; bpm, beats per minute; WR, work rate. Δ SBP = peak SBP – resting SBP. Δ heart rate = peak heart rate – resting heart rate. Data on resting diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was missing in one patient.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of resting systolic blood pressure vs peak systolic blood pressure during a symptom‐limited ergometer exercise test performed at baseline in 53 patients in the subacute phase after a stroke. Pearson correlation coefficient r = .355 (P = .009)

Figure 2.

Distributions of peak systolic blood pressures during an ergometer exercise test performed at baseline in 53 patients in the subacute phase after a stroke. Upper panel, women (n = 27); lower panel, men (n = 26)

3.2. Baseline functional capability

Baseline results from the 6‐minute walk test did not differ significantly between patients randomized to intervention and control, respectively (394.7 ± 114.7 m vs 391.6 ± 118.1 m, P = .923). There was also no difference in this regard between patients with or without an exaggerated BP response and patients with a normal BP response (389.1 ± 118.5 m vs 401.61 ± 111.1 m, P = .711).

3.3. Impact of the intervention on hemodynamic variables

Hemodynamic variables at baseline and at follow‐up are presented in Table 2. In the intervention group, Δ heart rate and peak work rate were significantly higher at 12 weeks than at baseline, but there was no such difference in the nonintervention group (Table 2). There were no significant changes from baseline to 12 weeks regarding resting diastolic BP or SBP, resting heart rate, peak SBP, peak heart rate, or Δ SBP, neither in the intervention group nor in the nonintervention group (Table 2). The proportions of patients with an exaggerated BP response to exercise did not change significantly from baseline to 12 weeks, neither in the intervention group (19/29 or 65.5% vs 18/29 or 62.1%, P = 1.000 [not in table]) nor in the nonintervention group (16/24 or 66.7% vs 17/24 or 70.8%, P = 1.000 [not in table]). At baseline, there were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and nonintervention groups in terms of values for resting diastolic BP (P = .892), resting SBP (P = .946), resting heart rate (P = .088), peak SBP (P = .600), Δ SBP (P = .577), Δ heart rate (P = .224), or peak work rate (P = .607), but peak heart rate was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the nonintervention group (P = .022) (P values not in table).

Table 2.

Hemodynamic variables at rest and during a symptom‐limited ergometer exercise test performed at baseline and after 12 weeks in 53 patients in the subacute phase after a stroke, stratified according to randomization

| Intervention group (n = 29) | Nonintervention group (n = 24) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow‐up | P value | Baseline | Follow‐up | P value | |

| Resting DBP, mm Hg | 77.1 ± 7.7 | 74.8 ± 7.8 | .130 | 77.8 ± 12.8 | 74.8 ± 7.9 | .171 |

| Resting SBP, mm Hg | 140.0 ± 23.4 | 135.0 ± 18.0 | .247 | 139.6 ± 20.4 | 133.8 ± 15.0 | .122 |

| Resting heart rate, bpm | 82.5 ± 12.3 | 80.1 ± 13.1 | .233 | 76.6 ± 12.5 | 77.4 ± 13.7 | .789 |

| Peak SBP, mm Hg | 204.1 ± 26.9 | 202.1 ± 28.8 | .617 | 208.1 ± 27.9 | 209.0 ± 24.0 | .849 |

| Peak heart rate, bpm | 144.9 ± 19.8 | 148.6 ± 19.0 | .162 | 132.8 ± 16.9 | 132.5 ± 19.3 | .841 |

| Δ SBP, mm Hg | 64.1 ± 30.3 | 67.1 ± 33.3 | .532 | 68.5 ± 25.9 | 75.2 ± 27.3 | .141 |

| Δ Heart rate, bpm | 62.4 ± 20.8 | 68.4 ± 19.3 | .041 | 56.2 ± 14.6 | 55.1 ± 20.3 | .731 |

| Aerobic capacity, peak WR, W | 115.7 ± 28.8 | 130.9 ± 33.3 | <.001 | 120.4 ± 37.2 | 121.7 ± 39.0 | .700 |

Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations.

P values denote pairwise comparisons between baseline and follow‐up values within randomization strata.

Abbreviations: bpm, beats per minute; SBP, systolic blood pressure, WR, work rate. Δ SBP = peak SBP – resting SBP; Δ heart rate = peak heart rate – resting heart rate. Data on resting diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was missing in one patient at baseline (in the intervention group) and in another patient at follow‐up (in the control group).

3.4. Antihypertensive medications

There were no statistically significant differences between baseline and follow‐up concerning the proportions of patients who did not use any BP‐lowering medications (5/53 or 9.4% vs 6/53 or 11.3%, P = 1.000), who used only one BP‐lowering medication (24/53 or 45.3% vs 21/53 or 39.6%, P = .549), who used two BP‐lowering medications (11/53 or 20.8% vs 12/53 or 22.6%, P = 1.000), or who used three or more BP‐lowering medications (13/53 or 24.5% vs 14/53 or 26.4%, P = 1.000).

The mean number of antihypertensive drugs that were used (not in table) also did not change significantly during the course of the trial (1.7 at baseline vs 1.6 at 12 weeks [P = .787] in patients randomized to intervention and 1.7 at baseline vs 1.9 at 12 weeks [P = .257] in patients randomized to nonintervention). The proportions of patients using medications from different antihypertensive drug classes at baseline and at 12 weeks are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antihypertensive drugs used at baseline and after 12 weeks in 53 patients in the subacute phase after a stroke

| Baseline | Follow‐up | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β‐Blocker | 17 (32.1) | 17 (32.1) | 1.000 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 19 (35.8) | 21 (39.6) | .687 |

| Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor | 20 (37.7) | 17 (32.1) | .375 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 18 (34.0) | 22 (41.5) | .125 |

| Spironolactone | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1.9) | 1.000 |

| Diuretic | 13 (24.5) | 14 (26.4) | 1.000 |

Values are expressed as number (percentage).

3.5. Safety analyses

There were no hospitalizations caused by cardiovascular events during the 12‐week trial, according to the patients' own statements and according to local medical records. No patient was excluded from the trial on the basis of abnormal ergometer test results, but among a total of 106 ergometer exercise tests, five tests (in four patients) were terminated early for concerns of safety. These events were the following: one patient had ECG changes, one patient (with known atrial fibrillation) had a marked increase in heart rate, one patient (with known atrial fibrillation and a pacemaker) had a marked decrease in heart rate, and one patient experienced a rapidly increasing SBP (both at baseline and at 12 weeks) that prompted the physician who supervised the stress tests to terminate the tests at both occasions, although the predetermined safety limit (SBP ≥ 280 mm Hg) was not reached. In addition to these five events, one patient with known atrial fibrillation experienced a marked drop in SBP during exercise, both at baseline and at 12 weeks, but both tests were terminated as a result of self‐reported general tiredness, rather than BP‐related safety concerns, according to the decision of the responsible physician who supervised the tests. The reasons for terminating the exercise tests at baseline and at 12 weeks are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reasons for terminating symptom‐limited ergometer exercise tests at baseline and after 12 weeks in 53 patients in the subacute phase after a stroke

| Baseline | Follow‐up | |

|---|---|---|

| Leg tiredness | 30 (56.6) | 28 (52.8) |

| Shortness of breatha | 9 (17.0) | 11 (20.8) |

| General tiredness | 8 (15.1) | 9 (17.0) |

| Knee pain | 3 (5.7) | 1 (1.9) |

| Back pain | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Dizziness | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) |

| Electrocardiographic changes | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) |

| Systolic blood pressure elevation | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) |

| Heart rate elevation | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Heart rate deceleration | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

Values are expressed as number (percentage).

Patients who reported combined shortness of breath and leg tiredness.

4. DISCUSSION

There were two major findings in this study of exercise BP reactions in patients in the subacute phase after stroke. First, we found that at baseline, an exaggerated BP response was common during a symptom‐limited ergometer exercise test: more than two of three patients exhibited an exaggerated BP response. In patients with elevated resting SBP, the corresponding proportion with an exaggerated BP response during the ergometer exercise test was even higher (3 of 4), and, in patients with normal resting SBP, as many as half of the patients still exhibited an abnormal rise in BP during the ergometer exercise test. Second, patients who were randomized to a 12‐week program of aerobic exercise training achieved a higher peak work rate at follow‐up than at baseline, and increased their heart rate more, but this was not accompanied by an increase in peak SBP.

We believe that the high prevalence of an exaggerated BP response during the baseline ergometer test is a finding of clinical importance. Steep elevations of BP during exercise in patients otherwise considered to have normotension may serve as a marker of masked hypertension,14, 15 ie, patients who actually have hypertension during home or ambulatory BP measurements despite having normotensive values in the usual clinical setting. Masked hypertension is an established marker for increased cardiovascular risk.16, 17, 18 Therefore, it has been advocated that individuals with apparent normotension who react with an exaggerated BP response during exercise tests should be evaluated with ambulatory or home BP measurements.12 Following this line of reasoning, our results suggest that following a stroke, patients with apparently well‐controlled resting BP could be considered candidates for ambulatory or home BP measurements.

It should be noted that we defined an exaggerated BP response as a rise of SBP to ≥ 210 mm Hg in men and a rise of SBP to ≥ 190 mm Hg in women based on commonly applied criteria,11, 12 but these cutoff values were derived from epidemiological data in patients without known cardiovascular disease.19 Peak exercise SBP is known to increase with increasing age,20 and our findings suggest that the BP response to exercise may need to be interpreted differentially in patients with established vascular disease than in apparently healthy individuals. Thus, definitions of what should be considered an abnormal BP response in patients with established vascular disease, as well as in the elderly, are urgently needed.

A study of patients with known coronary artery disease, 13% of whom also had a history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks, suggests that a greater BP increase during exercise is associated with a decreased risk for cerebrovascular disease as well as for all‐cause mortality.21 Furthermore, a study in elderly patients suggests that a greater BP increase during exercise is associated with a decreased risk for all‐cause mortality, but the baseline prevalence of previous cerebrovascular disease was not reported and stroke was not described as a separate outcome.22 On the other hand, a recent meta‐analysis of studies in patients free from cardiovascular disease found a significantly excessive risk for incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with an exaggerated BP response to moderate exercise intensity.23 In that meta‐analysis, cerebrovascular disease was not reported as a separate outcome, however.

The present study was not designed to address whether patients with stroke and a marked increase of SBP during exercise had an adverse long‐term prognosis compared with patients with a normal BP response. Given the high prevalence of exercise‐induced hypertensive responses in our cohort, and the lack of published data concerning associations between exercise BP and stroke recurrence, this seems to be an issue worthy of further investigation.

The level of fitness in patients after a stroke has previously been described in detail,7, 8, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 but, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to describe both peak SBP levels and the prevalence of an exaggerated BP response, as well as the effects of randomization to an aerobic exercise program on peak BP, in patients in the subacute phase after a stroke. Interestingly, previous studies of patients free from cardiovascular disease,31, 32 or at long‐term follow‐up after a stroke,30 have shown positive associations between randomization to aerobic exercise and reduced BP levels at fixed submaximal workloads. However, peak BPs were not reported in these trials, and one trial of patients with a recent transient ischemic attack actually showed that randomization to an 8‐week exercise program was associated with a nonsignificant trend towards increased peak SBP.6 In addition, one trial of elderly patients with hypertension or prehypertension found that randomization to exercise training increased peak BP significantly, despite lowering BPs measured at fixed submaximal workloads.5 In our trial, no such trend towards increasing peak BP was observed. Furthermore, no serious adverse events occurred during the trial, neither during the symptom‐limited ergometer exercise tests nor during the aerobic exercise sessions. Our findings are reassuring in terms of short‐term safety for aerobic exercise in subacute stroke. This may be an observation of clinical value, since almost one third of patients with a previous stroke have previously reported that health concerns prevent them from performing exercise training.33 It should be emphasized, however, that this trial was not designed to evaluate the safety of intensive aerobic exercise in patients with stroke. This would require a considerably larger study and a longer follow‐up time.

One plausible explanation to the finding that aerobic exercise training was associated with higher peak work rate and higher Δ heart rate at follow‐up than at baseline, but that this was not accompanied by an increase in peak SBP, could be that aerobic exercise led to improved endothelial function. This would have attenuated the BP surge otherwise expected to occur in parallel with increased Δ heart rate. We did not measure endothelial function in this trial, but a beneficial effect of exercise on vascular parameters such as flow‐mediated dilation has been demonstrated by others in patient populations with established cardiovascular disease or risk factors, such as in patients with heart failure,34 coronary artery disease35 and type 2 diabetes mellitus.36

5. STUDY LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

As always, our results should be interpreted within the context of the limitations of the study. First, the lack of an age‐matched control group without a history of cerebrovascular disease precludes us from analyzing whether stroke per se is associated with the BP response to exercise. Second, the present analysis represents a post hoc analysis of a previously performed clinical trial, which was not specifically designed to evaluate BP responses to exercise. Thus, although measurements of BP were recorded according to conventional clinical routines by experienced clinical physiologists, there is a tendency towards digit preference concerning SBP values, ie, BP values were generally rounded to the nearest 5 or 10 mm Hg rather than to the nearest 2 mm Hg as recommended in current hypertension guidelines.12 Furthermore, BPs at submaximal workloads were not systematically reported during the ergometer exercise test and thus cannot be subject to analysis in this trial. Third, changes of antihypertensive drugs were allowed at the discretion of the treating physician. Although there seemed to have been no major changes in the proportions of patients who used any specific antihypertensive drug class within the entire cohort, or in the mean number of antihypertensive drugs that were used in either of the randomization groups, we have no data concerning the doses used and we cannot exclude that treatment changes or dose titrations made during the trial affected the BP outcome parameters. This is an important study limitation, but we also believe that it strengthens the clinical applicability of our results, since physical exercise took place as add‐on to usual clinical care. Finally, the small sample size calls for a cautious interpretation of our data and precludes us from performing subgroup analyses.

We believe that certain characteristics from the present study may prove to be helpful if similar exercise programs are to be implemented in clinical care early after a stroke. First, patients and their relatives were informed by physiotherapists early after the stroke, already during the hospital care phase. Second, there was a clear connection between medical care and exercise throughout the whole intervention period, and the intervention was medically accepted at the stroke unit. Third, the personnel who led the exercise intervention had long experience from stroke rehabilitation.

6. CONCLUSIONS

We found that an exaggerated SBP response was common in patients after a stroke, even when resting SBP was normal. We also found that the beneficial effects of the aerobic exercise intervention, in terms of improved aerobic capacity, walking ability, balance, and self‐reported quality of life and recovery, which have been previously published,9 were achieved without any significant increase in peak SBP.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Wijkman MO, Sandberg K, Kleist M, Falk L, Enthoven P. The exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise in the sub‐acute phase after stroke is not affected by aerobic exercise. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20:56–64. 10.1111/jch.13157

REFERENCES

- 1. Cornelissen VA, Buys R, Smart NA. Endurance exercise beneficially affects ambulatory blood pressure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Hypertens. 2013;31:639‐648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gordon NF, Gulanick M, Costa F, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention; the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; and the Stroke Council. Circulation. 2004;109:2031‐2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nishioka Y, Sashika H, Andho N, Tochikubo O. Relation between 24‐h heart rate variability and blood pressure fluctuation during exercise in stroke patients. Circ J. 2005;69:717‐721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kurl S, Laukkanen JA, Rauramaa R, et al. Systolic blood pressure response to exercise stress test and risk of stroke. Stroke. 2001;32:2036‐2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barone BB, Wang NY, Bacher AC, Stewart KJ. Decreased exercise blood pressure in older adults after exercise training: contributions of increased fitness and decreased fatness. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:52‐56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Faulkner J, McGonigal G, Woolley B, et al. The effect of a short‐term exercise programme on haemodynamic adaptability: a randomised controlled trial with newly diagnosed transient ischaemic attack patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:736‐743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mackay‐Lyons MJ, Makrides L. Exercise capacity early after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1697‐1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelly JO, Kilbreath SL, Davis GM, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and walking ability in subacute stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1780‐1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sandberg K, Kleist M, Falk L, Enthoven P. Effects of twice‐weekly intense aerobic exercise in early subacute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:1244‐1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borg G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1970;2:92‐98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharman JE, LaGerche A. Exercise blood pressure: clinical relevance and correct measurement. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29:351‐358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281‐1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, et al. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743‐749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schultz MG, Hare JL, Marwick TH, et al. Masked hypertension is “unmasked” by low‐intensity exercise blood pressure. Blood Press. 2011;20:284‐289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharman JE, Hare JL, Thomas S, et al. Association of masked hypertension and left ventricular remodeling with the hypertensive response to exercise. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:898‐903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bjorklund K, Lind L, Zethelius B, et al. Isolated ambulatory hypertension predicts cardiovascular morbidity in elderly men. Circulation. 2003;107:1297‐1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, et al. Prognosis of “masked” hypertension and “white‐coat” hypertension detected by 24‐h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring 10‐year follow‐up from the Ohasama study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:508‐515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bobrie G, Clerson P, Menard J, et al. Masked hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1715‐1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lauer MS, Levy D, Anderson KM, Plehn JF. Is there a relationship between exercise systolic blood pressure response and left ventricular mass? The Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:203‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Daida H, Allison TG, Squires RW, et al. Peak exercise blood pressure stratified by age and gender in apparently healthy subjects. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:445‐452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Habibzadeh MR, Farzaneh‐Far R, Sarna P, et al. Association of blood pressure and heart rate response during exercise with cardiovascular events in the Heart and Soul Study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:2236‐2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hedberg P, Ohrvik J, Lonnberg I, Nilsson G. Augmented blood pressure response to exercise is associated with improved long‐term survival in older people. Heart. 2009;95:1072‐1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schultz MG, Otahal P, Cleland VJ, et al. Exercise‐induced hypertension, cardiovascular events, and mortality in patients undergoing exercise stress testing: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:357‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tang A, Sibley KM, Thomas SG, et al. Maximal exercise test results in subacute stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1100‐1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen JK, Chen TW, Chen CH, Huang MH. Preliminary study of exercise capacity in post‐acute stroke survivors. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2010;26:175‐181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yates JS, Studenski S, Gollub S, et al. Bicycle ergometry in subacute‐stroke survivors: feasibility, safety, and exercise performance. J Aging Phys Act. 2004;12:64‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marzolini S, Oh P, McIlroy W, Brooks D. The feasibility of cardiopulmonary exercise testing for prescribing exercise to people after stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:1075‐1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nadeau SE, Rose DK, Dobkin B, et al. Likelihood of myocardial infarction during stroke rehabilitation preceded by cardiovascular screening and an exercise tolerance test: the Locomotor Experience Applied Post‐Stroke (LEAPS) trial. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:1097‐1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rimmer JH, Rauworth AE, Wang EC, et al. A preliminary study to examine the effects of aerobic and therapeutic (nonaerobic) exercise on cardiorespiratory fitness and coronary risk reduction in stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:407‐412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Potempa K, Lopez M, Braun LT, et al. Physiological outcomes of aerobic exercise training in hemiparetic stroke patients. Stroke. 1995;26:101‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cornelissen VA, Verheyden B, Aubert AE, Fagard RH. Effects of aerobic training intensity on resting, exercise and post‐exercise blood pressure, heart rate and heart‐rate variability. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:175‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Swift DL, Earnest CP, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. The effect of different doses of aerobic exercise training on exercise blood pressure in overweight and obese postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:503‐509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rimmer JH, Wang E, Smith D. Barriers associated with exercise and community access for individuals with stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45:315‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pearson MJ, Smart NA. Effect of exercise training on endothelial function in heart failure patients: a systematic review meta‐analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017;231:234‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luk TH, Dai YL, Siu CW, et al. Effect of exercise training on vascular endothelial function in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:830‐839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Montero D, Walther G, Benamo E, et al. Effects of exercise training on arterial function in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Sports Med. 2013;43:1191‐1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]