Abstract

The aim of this study was to improve the diagnostic efficiency for juxtaglomerular cell tumors (JCTs) and to determine whether clinical and magnetic resonance imaging features can help to differentiate JCTs from clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). The clinical features of eight patients with JCTs and 27 patients with ccRCCs were analyzed. A flow diagram for young people with hypertension was applied to facilitate the diagnosis. Clinical presentations were analyzed, including age, hypertension, and hypokalemia. The results of our study produced a flow diagram that narrowed the scope of diagnosis. The statistical results demonstrated that patients with a renal mass aged 14 to 30 years, had grade 3 hypertension, or had moderate hypokalemia had a greater possibility of having a JCT than a ccRCC (P<.0000, P<.01, P<.0005, respectively). In addition, the flow diagram and magnetic resonance imaging features were useful to distinguish JCTs from other renal tumors.

A juxtaglomerular cell tumor (JCT) of the kidney, also known as reninoma, is a rare life‐threatening renal neoplasm that was first described by Robertson and colleagues1 in 1967.

When untreated, a JCT can cause progressive hypertension that may result in a cerebrovascular accident and even death.2 It is essential to diagnose these patients early and to manage them selectively.

Although the clinical manifestations of JCT, which consist of hypertension, hyperreninemia, and secondary aldosteronism occurring mainly in adolescents and young adults, have been previously described in several studies,3, 4, 5, 6, 7 the diagnosis of JCT remains challenging because considerable ambiguities are present when interpreting laboratory and radiological studies.8 Osawa and colleagues5 reported one patient who received a delayed diagnosis after 17 years. Furthermore, the longest delay in diagnosis in our study was 7 years. Several potential reasons for this finding exist. A JCT is a rare neoplasm, and many physicians are not familiar with the condition. Moreover, it is essential to understand how to diagnose JCT in an adolescent or young adult presenting with hypertension in a clinical setting.

Indeed, the clinical manifestations and reference values for laboratory examinations have been described for JCT. However, the overlap in diagnostic characteristics decreases the accuracy between the diagnosis of JCT and other tumors that can cause hypertension.

The differential diagnosis of JCT is nearly nonexistent relative to other renal tumors that also cause hypertension (eg, renal cell carcinoma [RCC]).9 Case studies have reported that renin‐producing or aldosterone‐producing clear cell RCC (ccRCC)10, 11 can resemble cases of atypical or nonfunctioning JCT.12, 13 In our clinical practice, we sometimes encounter patients with ccRCC complicated by hypertension or hypokalemia. It is difficult and important to make a distinct preoperative diagnosis between JCT and ccRCC. A benign renal tumor does not require the excision of additional peritumoral renal parenchyma if a renal mass requires surgical removal.

To the best of our knowledge, our study of eight JCT patients is the largest series reported to date. The purposes of the present study were to develop reference values for a diagnostic flow diagram for adolescents and young adults with hypertension and to compare the various clinical features of JCT with those of ccRCC to obtain more comprehensive knowledge.

Methods

The procedures of this study were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Our institutional review board approved this retrospective study (the ethical committee of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, on May 6, 2015), and written informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

Diagnostic Flow Diagram for Hypertension in Adolescents and Young Adults

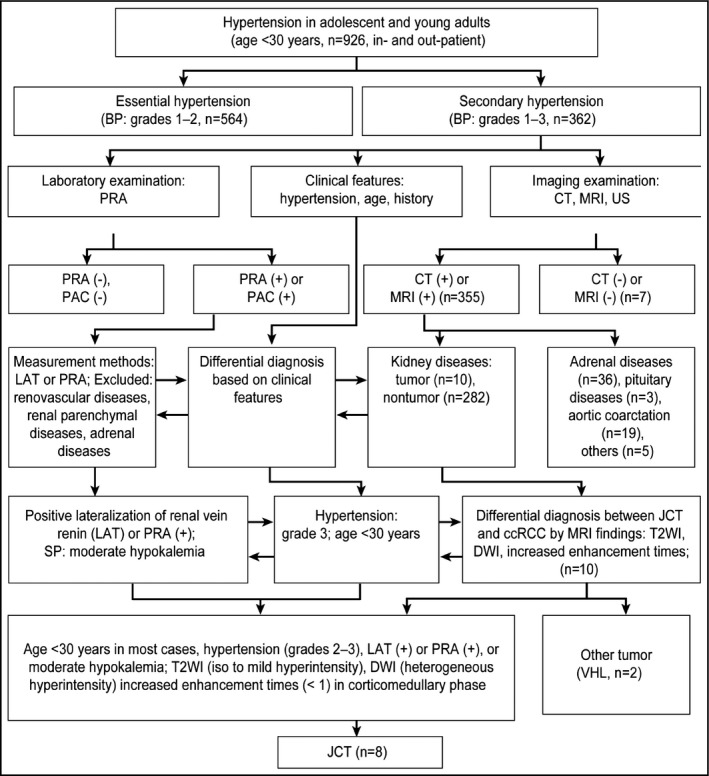

Three steps are critical in diagnosing a young person with hypertension (Figure 1). The initial step is to distinguish between essential hypertension and secondary hypertension. If secondary hypertension is present, then the second step is to determine whether hypertension is caused by a tumor. If a renal tumor is found, then the third step is to determine whether it is an RCC or a JCT. According to this procedure, we diagnosed secondary hypertension in 362 of 926 patients 30 years or older from January 2010 to March 2015.

Figure 1.

The diagnostic flow diagram of JCT before operation. BP, blood pressure; PRA, plasma renin activity; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasonography; PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; LAT, lateralization of renal vein; SP, serum potassium; JCT, juxtaglomerular cell tumor; ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma; T2WI, T2‐weighted imaging; DWI, diffusion‐weighted imaging; VHL; Von Hippel‐Lindau.

Based on the literature4, 5, 6, 7 and our own experiences, we designed a flow diagram to help identify the causes of a diagnosis of hypertension in adolescents and young adults. The generation of this diagram included the following steps. First, all of the patients were divided into two groups. One group consisted of patients with essential hypertension (546 cases), and the other group consisted of patients with secondary hypertension (362 cases). The causes of essential hypertension included obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and a family history of hypertension, among others. Diastolic blood pressure (BP) increases distinctly, whereas systolic blood pressure (BP) does not clearly increase, which is the important characteristic in young patients with essential hypertension. Essential hypertension can be controlled using antihypertensive agents in most cases, which is considered primary hypertension. The others are secondary hypertension. The causes of secondary hypertension include adrenal disease (ie, hyperaldosteronism, secondary hyperaldosteronism, pheochromocytoma or ectopic pheochromocytoma, and functional adrenocortical adenoma), renovascular hypertension (ie, renal artery stenosis, artery or vein thrombosis, and Takayasu arteritis), renal parenchymal disease, and other tumors (ie, Wilms tumor and RCC).

Adrenal gland disease is one of the primary causes of secondary hypertension and comprises mainly three types of diseases. The first is primary aldosteronism, which always shows an increased level of aldosterone and decreased plasma renin activity. Primary aldosteronism is efficiently treated with spironolactone. The second is Cushing syndrome (CS). An 11 pm salivary cortisol level is a modern, simple initial screening tool for the diagnosis of CS, with high sensitivity and specificity.14 Confirmatory tests include 24‐hour urinary free cortisol levels and/or low‐dose dexamethasone suppression tests, which support the diagnosis of CS when positive. The third is pheochromocytoma or ectopic pheochromocytoma. This disease always manifests as intermittent or persistent hypertension, and the level of catecholamine in blood and urine is increased. Secondary hypertension is not well controlled using antihypertensive agents.

The second step was to be certain of the causes of hypertension. Using imaging examinations, such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or conventional ultrasound, the main organs were examined for factors causing secondary hypertension. Imaging examinations and related laboratory tests were performed on patients with kidney diseases (292 cases), adrenal gland diseases (36 cases), pituitary gland diseases (three cases), and diseases of the aorta (24 cases). After a renal mass was found (10 cases), the third step was to perform a differential diagnosis based on the clinical characteristics and imaging findings. These steps are shown in the flow diagram (Figure 1).

One of the most important steps was the differential diagnosis between JCT and other malignant renal tumors. The diagnostic trial is described in the following section.

Experimental Protocol to Determine Clinical and Imaging Features

To determine whether clinical features can help to differentiate JCT from other renal neoplasms, we performed a retrospective review of a pathology database of patients who underwent surgery for a renal neoplasm (either partial or total nephrectomy) at our institution. The study was performed on two sets of patients. The first set included eight patients with JCTs (five male and three female patients). The second set included the control group, consisting of 27 patients with ccRCC (19 male and 8 female patients, aged 29–80 years) who were randomized from 69 cases of ccRCC with size‐matched tumors <5 cm.15

The 69 patients were randomized by patient serial number according to when each procedure was performed. Using SPSS version 19.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA), 27 random numbers were generated for the control group.

Each patient had a single tumor. The eight JCT patients had undergone an unenhanced axial MRI scan and dynamic contrast enhancement. Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the eight JCT patients.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Eight Patients With a Juxtaglomerular Cell Tumor

| Case No. | Age, y/Sex | Clinical Presentation | Findings During Diagnostic Evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBP, History | Findings | SP | PRA, su/up | PRA LAT | Ang II, su/up | PAC, su/up | Organ Damage | Tumor Size, cm, Location | ||

| 1 | 17/F | 190/140, 5 d | Hypertension on routine examination | 3.68 | 9.8/12.8 | – | 88.5/07.6 | 483.0/673.7 | – | 2.5×2.3, R |

| 2 | 28/M | 220/140, 7 y | Hypertension on routine examination | 3.22 | 15.9/16.4 | NA | 549.5/838.1 | 925.2/973.1 | Cerebral ischemia, papilledema III | 4.1×3.9, L |

| 3 | 23/M | 180/120, 4 y | Nausea, vomiting | 2.56 | 2.7/7.7 | NA | 1126.9/838.9 | 512.9/702.1 | – | 2.7×3.2, R |

| 4 | 27/F | 201/147, 30 d | Hypertension on routine examination | 2.6 | 9.1/12 | NA | 117.6/336.1 | 534.1/822.9 | NA | 2.7×2.3, R |

| 5 | 22/F | 210/150, 8 y | Intermittent headaches, nausea, vomiting | 3.07 | 17.0/12.1 | + | 245.7/>800 | 447.4/709.6 | NA | 3.1×2.0, R |

| 6 | 23/M | 170/100, 5 y | Headaches, nausea, vomiting | 3.88 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Cerebral ischemia | 3.5×2.5, L |

| 7 | 30/M | 210/135, 30 d | Hypertension on routine examination | 2.72 | 7.8/12.5 | + | 85.7/331.1 | 713.0/740.7 | NA | 1.7×1.4, L |

| 8 | 18/M | 220/120, 270 d | Headaches, cerebral hemorrhage | 3.82 | 6.6/6.3 | NA | 124.6/56.6 | 386.2/515.4 | Cerebral hemorrhage | 3.5×3.0, R |

Abbreviations: Ang II, angiotensin II (ng/L), with a normal value of 28.2 ng/L to 52.2 ng/L in a supine position and 55.3 ng/L to 115.3 ng/L in an upright position; HBP, highest blood pressure (mm Hg); L, left; LAT, lateralization of renal vein; NA, not available; PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration (pmol/L), with a normal value 163.4 pmol/L to 489.1 pmol/L in a supine position and 180.1 pmol/L to 819.9 pmol/L in an upright position; PRA, plasma renin activity (ng/mL/h) with a normal value <0.79 μg/L/h in a supine position and 0.93 μg/L/h to 6.56 μg/L/h in an upright position; R, right; SP, serum potassium (mEq/L); su, supine position; up, upright position.

All patients in this cohort study met specific inclusion criteria. In addition, all patients had complete clinical data and did not have adrenal diseases or renal artery stenoses. Patients were excluded if they had renovascular disease (eg, renal artery stenosis), renal parenchymal disease (eg, renal dysplasia, scarring, or glomerulonephritis), or other renin‐secreting tumors (eg, Wilms tumor); if complete clinical data could not be obtained; or if they had developed renal insufficiency or other nutritional, metabolic, and endocrine disorders.

Some clinical features and imaging findings between JCT and ccRCC may be similar. Because hypertension is one of the known risk factors for RCC,16, 17 some patients had hypertension. The serum potassium levels in certain RCC patients were lower than the normal value due to their complicated clinical condition. In addition, ccRCC accounts for approximately 70% to 80% of RCC cases18 thus, the diagnosis of JCT partially overlapped with that of RCC.

Most patients with ccRCC in this study did not have urinary symptoms. Only a few patients complained of lumbago and gross hematuria. The BP values were slightly higher than the normal systolic pressure value in 12 of 27 patients.

The three clinical parameters that were analyzed in this study—age (adolescents and young adults), BP (hypertension), and serum potassium (hypokalemia)—are regarded as the clinical characteristics of JCT in most reports.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 These three clinical indices are also the most commonly used parameters in clinical examinations because of their values and ease in diagnosing different diseases.

Patients were categorized as having normal BP or hypertension. Normal BP was defined as a systolic BP <140 mm Hg and a diastolic BP <80 mm Hg. According to a study by Liu,19 hypertension can be categorized as grade 1 (systolic pressure 140 mm Hg to 159 mm Hg and diastolic pressure 90 mm Hg to 99 mm Hg); grade 2 (systolic pressure 160 mm Hg to 179 mm Hg and diastolic pressure 100 mm Hg to 109 mm Hg); and grade 3 (systolic pressure ≥180 mm Hg and diastolic pressure ≥110 mm Hg). For the patients with JCT, the mean systolic and diastolic pressures are listed in Table 3. According to Eliacik and colleagues,20 serum potassium levels can be classified as normal or hypokalemic. Normal serum potassium levels range between 3.5 mmol/L and 5.5 mmol/L. Hypokalemia is defined as potassium levels <3.5 mmol/L, with mild hypokalemia at 3.01 mmol/L to 3.49 mmol/L and moderate disease at 2.5 mmol/L to 3.0 mmol/L.

Table 3.

Quantitative Characteristics of JCT and ccRCC

| Quantitative Variable | JCT (n=8) Mean±SD | ccRCC (n=27) Mean±SD | P Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y | 20.27±4.629 | 51.59±10.775 | .0000 | 23.22–39.42 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L | 3.194±0.547 | 3.879±0.369 | .038 | −1.229 to −0.0462 |

| Systolic pressure, mm Hg | 197.63±16.716 | 130.19±13.261 | .0001 | 46.505–86.495 |

| Diastolic pressure, mm Hg | 130.25±18.180 | 79.70±12.603 | .0000 | 32.299–67.701 |

Abbreviations: ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; JCT, juxtaglomerular cell tumor; SD, standard deviation.

In this study, patients were classified into four age groups: 14 to 30 years, 31 to 45 years, 46 to 60 years, and older than 61 years. Table 2 lists the clinical presentations of the patients with JCT and ccRCC.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Qualitative Clinical Characteristics Between JCT and ccRCC

| Qualitative Variable | Case Group | |

|---|---|---|

| JCT (n=8) | ccRCC (n=27) | |

| Age, y | ||

| 14–30 | 8 | 1 |

| 31–45 | 0 | 7 |

| 46–60 | 0 | 13 |

| 61–80 | 0 | 6 |

| Systolic pressure, mm Hg | ||

| 120–139 | 0 | 15 |

| 140–159 | 0 | 12 |

| 160–179 | 1 | 0 |

| ≥180 | 7 | 0 |

| Diastolic pressure, mm Hg | ||

| <89 | 0 | 19 |

| 90–99 | 0 | 4 |

| 100–109 | 1 | 4 |

| ≥110 | 7 | 0 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L | ||

| ≥3.5 | 3 | 22 |

| 3.01–3.49 | 2 | 5 |

| 2.50–3.00 | 3 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma; JCT, juxtaglomerular cell tumor.

Other Laboratory Indices

Plasma renin activity (PRA), angiotensin II (Ang II) level, and plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) were tested in the JCT group. Three of eight patients also underwent measurement by lateralization of the renal vein renin.

BP and Biochemical Examination

BP was measured using an electronic sphygmomanometer (HEM‐7112; Omron, Kyoto, Japan). The biochemical examination was performed using a fully automatic biochemical analyzer (Cobas 8000 with the c 701 module; Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland).

Imaging Examination

All patients underwent upper abdominal unenhanced and dynamic contrast‐enhanced MRI scans. Six JCT patients underwent a cranial MRI scan. MRI examinations were performed using a 1.5‐T and 3.0‐T MR imaging system (TwinSpeed Signa EXCITE HD; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). Before the administration of the contrast agent, the signal on T2‐weighted imaging (T2WI) and T1‐weighted imaging (T1WI), the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value, and the increased enhancement times in the corticomedullary phase were analyzed independently by three radiologists.

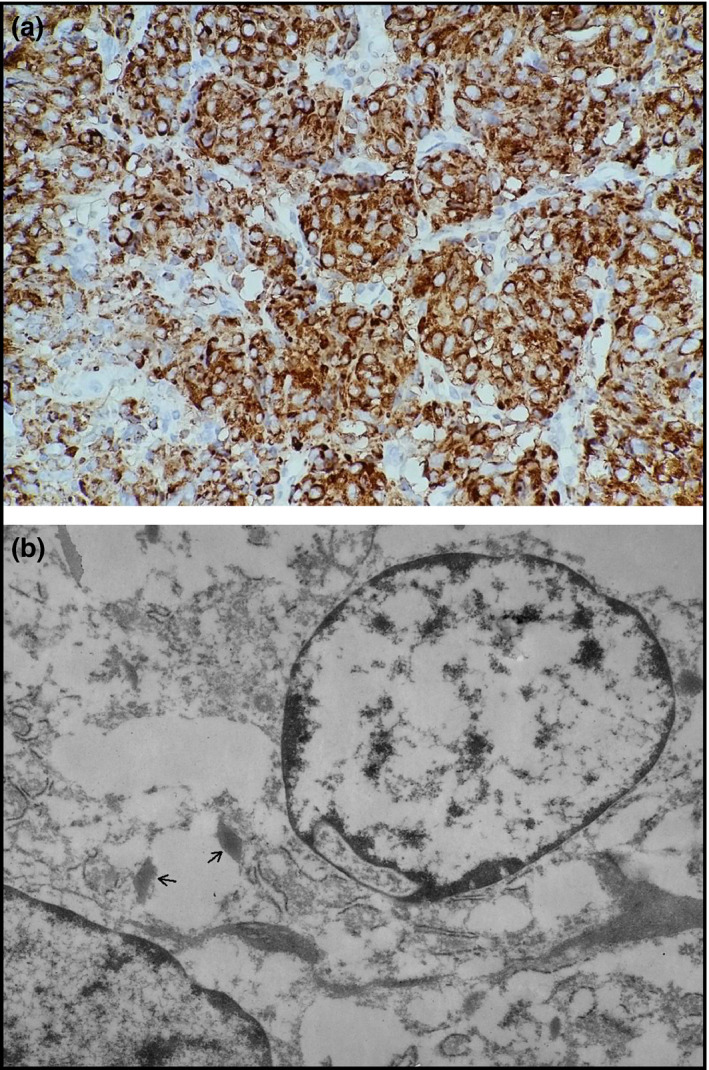

Pathological Analysis

To confirm the diagnosis of JCT or ccRCC, pathologic specimens from all the patients were reviewed retrospectively by a pathologist according to World Health Organization 2004 pathologic diagnostic criteria.21 Immunohistochemical studies were also performed. The cytoplasm of the tumor cells expressed renin. Abundant endoplasmic rhomboid crystalline renin granules were found ultrastructurally (Figure 2a and 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Light microscopy, renin ×100; (b) Electron microscopy, ×6000; renin‐like granules (arrows).

Statistical Analysis

If the quantitative data fit a normal distribution, then Student t test was performed; otherwise a t‐test was performed. The mean, standard deviation, and median were evaluated for the distribution of quantitative continuous variables for the eight patients with a JCT and 27 patients with ccRCC. To analyze the relationships among the quantitative data, the data were transformed into grade data. A nonparametric Kruskal‐Wallis H test was used to compare the central tendency of the distributions between the two groups of lesions. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 software and CHISS software (Beijing Yuanyitang Science and Technology Ltd., Beijing, China). A P value<.05 was considered significant. The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy rate, and Youden index were calculated.

Results

Diagnostic Flow Diagram for Hypertension in Adolescents and Young Adults

Before using the flow diagram, we examined two patients with JCTs from January 2010 to December 2012. We found that one diagnosis was correct and the other was incorrect. After using the diagram from January 2013 to March 2015, we made correct diagnoses of JCT for five of six patients before surgery. The incorrect diagnosis was made in a patient for whom other potential diagnoses were not excluded according to the detailed flow diagram. Indeed, the flow diagram was also suitable for the two patients in the former period. The diagnostic flow diagram displays reference values for adolescents and young adults with hypertension. After surgery, the BPs of all the patients were normal. No patient was found to have concurrent JCT and adrenal gland disease.

Clinical Features

A pathological diagnosis was achieved using a partial nephrectomy (n=7) or radical nephrectomy (n=1) in the eight patients with JCT, and a radical nephrectomy (n=17) or partial nephrectomy (n=10) was used for the 27 patients with ccRCC. Patients with JCT were significantly younger than those with ccRCC. The serum potassium levels of patients with JCT were lower than their ccRCC counterparts. Both the systolic and diastolic pressures of patients with JCT were higher than in patients with ccRCC (Table 3).

The nonparametric Kruskal‐Wallis H test was used to determine any statistically significant difference.

Age

In the 14‐ to 30‐year age group, the probability of developing JCT was higher than that of developing ccRCC (P=.0000). With advancing age, the probability of developing JCT became lower than that of developing ccRCC.

Systolic Pressure

In the group with normal pressure, the probability of developing JCT was lower than that of developing ccRCC (P=.0000). The probability of developing JCT increased with increasing BP, and the probability of patients with grade 3 hypertension developing JCT was higher than that of patients in the normal pressure and grade 1 hypertension groups (P<.01).

Diastolic Pressure

In the normal pressure group, the probability of developing JCT was lower than that of developing ccRCC (P=.000). The probability of developing JCT increased with increasing BP, and the probability of patients with grade 3 hypertension developing JCT was higher than that of them developing ccRCC and higher than that of patients in the normal pressure and hypertension grade 1 or 2 groups (diastolic pressure).

Serum Potassium

The probability of developing JCT in the normal serum potassium group was lower than of them developing ccRCC (P=.0079). The probability of patients with potassium levels of 2.5 mmol/L to 3.0 mmol/L (moderate hypokalemia) developing JCT was higher than that of patients with levels ≥3.5 mmol/L (normal value) (P<.01).

Other Laboratory Results

Seven of eight patients with JCT were administered laboratory tests to detect PRA, Ang II levels, and PAC. The PRA value ranged from >2.78 to 20.1 times that of the normal value in the supine position and from >0 to 2.5 times the normal value in the upright position. Lateralization of renal vein renin was positive in two of three patients. Renal function and urine catecholamine values were normal in all cases.

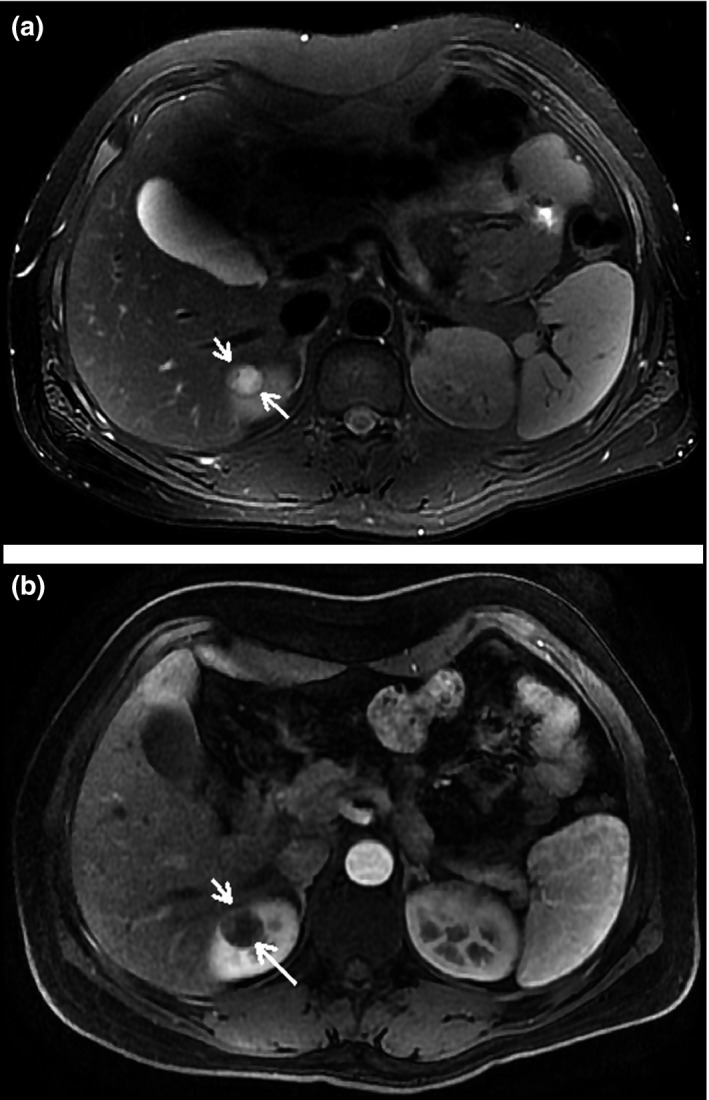

Imaging Examination

Isointensity or mild hyperintensity on T2WI, lower ADC values showing heterogeneous hyperintensity on diffusion‐weighted imaging (DWI), and a <200% degree of enhancement were found in the corticomedullary phase; these differences were statistically significant compared with those in patients with ccRCCs (P<.05, P=.0029, P=.0010, respectively) (Figure 3a and 3b). Cerebral infarction (2 of 8) and hemorrhage (1 of 8) were also found on MRI scans.

Figure 3.

(a) An 18‐year‐old man with a solid tumor on the pole of the right kidney. On T2‐weighted image, the lesion (short arrow) shows mild hyperintensity with a low‐signal capsule (long arrow). (b) On the corticomedullary phase image, the lesion (short arrow) indicates a mild enhancement.

Other Nonspecific Symptoms

Headache (3 of 8), nausea, and vomiting (3 of 8) were relatively common symptoms. Hazy vision (1 of 8) caused by grade III papilledema was observed. No symptoms were found to cause mild to moderate hypokalemia.

Validity of Each Index for Differentiation Between JCT and ccRCC

The sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index of age were higher than those of other parameters (Table 4). The validity of grade 3 hypertension showed better results than the other parameters. Regarding the MRI characteristic findings, Youden index of lower ADC on DWI and isointensity or mild hyperintensity on T2WI showed higher values than the other parameters. When the combination of a lower ADC value on DWI and a <200% degree of enhancement in the corticomedullary phase were tested using a parallel test, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy rate, and Youden index were 90.9%, 91.7%, 91.4%, and 0.826, respectively.

Table 4.

Validity of Different Indices for Differentiation Between Juxtaglomerular Cell Tumor and Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

| Index Test | Validity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Youden Index | Accuracy Rate, % | |

| Age, y | 100 | 96.3 | 0.963 | 97.1 |

| Grade 3 hypertension ② | 87.5 | 100 | 0.875 | 97.1 |

| Moderate hypokalemia ③ | 84.4 | 100 | 0.844 | 85.7 |

| Lower ADC value (DWI) ④ | 91.7 | 91.7 | 0.834 | 87.5 |

| Isointensity or mild high SI on T2WI ⑤ | 87.5 | 95.8 | 0.833 | 93.8 |

| Corticomedullary phase SI increased <1, ⑥ | 62.5 | 91.7 | 0.542 | 84.4 |

| ④+⑥ (parallel test) | 90.9 | 91.7 | 0.826 | 91.4 |

| ④+⑥ (series test) | 45.5 | 91.7 | 0.371 | 80.1 |

Abbreviations: ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion‐weighted imaging; SI, signal intensity; T2WI, T2‐weighted imaging.

Discussion

A JCT of the kidney is a rare renal neoplasm. Haab and colleagues22 reported only eight cases of JCT among 30,000 hypertensive patients during a 15‐year period. JCTs originate from the modified smooth muscle cells that compose the vascular component of the juxtaglomerular apparatus.23

In the diagnosis of adolescents and young adults with hypertension, an important step consists of distinguishing between essential and secondary hypertension. After excluding essential hypertension, the cause of secondary hypertension should be fully explored. Renal diseases, including renovascular and renal parenchymal disease and other renin‐secreting tumors, such as JCT, were the second most prevalent cause of secondary hypertension in adolescents and young adults in our study. The diagnostic flow diagram can help to narrow the scope of the diagnosis and improve efficiency.

We provide evidence that JCTs are more often present in patients aged 14 to 30 years than in other age groups. McVicar and colleagues4 showed that 78.9% of patients with JCTs were younger than 30 years. The probability of patients older than 31 years having a JCT was lower than that for patients younger than 30 years. Previous studies have shown that a gain in chromosome 10 as well as a loss in chromosome 9, the X chromosome, and most of chromosome arm 11q might be important pathogenetic events for JCTs.24 Because JCTs may be genetically inherited, the mean age of onset is younger than that for patients with ccRCCs, except for the hereditary type. In addition, JCTs might be involved in the presentation of a severe degree of hypertension. Childhood hypertension is often asymptomatic and is easily missed.25 Hypertension impairs arterial compliance and distensibility. The atherosclerotic process begins in youth and is accelerated by increased BP.26

Our results demonstrated that patients aged 14 to 30 years with grade 3 hypertension (systolic pressure) were more likely to have a JCT than patients with normal BP or grade 1 hypertension (systolic pressure). In our study, seven of eight patients had grade 3 hypertension, and 43.3% of patients with ccRCCs had grade 1 hypertension. Our study indicated that patients with grade 1 hypertension were more likely to have ccRCC. However, the scenario is very different for grade 3 hypertension. In this study, we found that grade 1 and 2 hypertension did not indicate that a patient had a higher chance of developing JCT.

Patients with grade 3 hypertension (diastolic pressure) had a greater possibility of developing JCT than patients with normal BP or grade 1 or 2 hypertension. Other nonspecific symptoms and cerebral infarctions or hemorrhages caused by grade 3 hypertension lasted for a relatively long time.

JCT can be categorized as functional or nonfunctional.4, 13 Patients younger than 30 years with a functional JCT may secrete an excessive amount of renin. Grade 3 hypertension is the main symptom in most cases of JCT (seven of eight patients in our study). The cause of grade 3 hypertension is secondary to the secretion of an excessive amount of renin. Ang II mediated by renin is a potent vasopressor. This hormone plays an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and hypertension.27 Consequently, JCTs mainly cause grade 3 hypertension. In contrast, atherosclerotic hypertension, one of the multiple risk factors for RCC, always shows grade 1 hypertension.

The nonfunctioning variant of JCT is the rarest form and is believed to produce inactive renin.12 We did not find this type of JCT in our study.

We found that patients younger than 30 years with moderate hypokalemia (2.5–3.0 mmol/L) were more likely to have a JCT than patients with normal or slight hypokalemia. Elevated plasma renin activity results in hyperaldosteronism, with subsequent hypokalemia, in most patients.28, 29

The relationship between aldosterone and serum potassium might occur because these patients have a relatively long JCT history and always demonstrate hypokalemia. A potential reason for this hypokalemia may be the high aldosterone stimulation of sodium‐potassium exchange by the principal cells of the collecting duct, resulting in excessive potassium loss in urine, the depletion of potassium stores in the body, and the stimulation of proton secretion by the intercalated cells of the renal collecting duct.30 In contrast, patients with a relatively short JCT history always show normal serum potassium levels. Another potential reason is because antihypertensive medication reduces the amount of Ang II and aldosterone.

Interestingly, patients aged 14 to 30 years with moderate hypokalemia (2.5–3.0 mmol/L) are deemed to have one of the clinical features of JCT once a renal mass is found.

In theory, positive lateralization of renal vein renin is the most accurate index for JCT. However, this is not always the case. One of three patients in our study was negative, and 50% of the cases were negative for lateralization in the literature.3 This result was affected by other factors, such as the effects of the antihypertensive therapy, the segmental secretion of renin, and dilution or local suppression.3, 31 The elevated levels of PRA were also beneficial for JCT.

Imaging examinations play an important role in the diagnosis process. They can help to exclude adrenal and pituitary disease. Compared with CT, MRI without ionizing radiation is the most appropriate examination for adolescents and young adults. Characteristic MRI findings, such as lower ADC, isointensity or mild hyperintensity on T2WI, and a <200% degree of enhancement in the corticomedullary phase, are important reference values for JCT.

The validity of age was higher than that of other parameters, and grade 3 hypertension was better for predicting JCT compared with other parameters. The validity of some MRI findings was also relatively high.

This study was limited by the number of patients with JCT and the incomplete clinical data obtained from the group of patients with ccRCC.

Conclusions

The flow diagram for hypertension in adolescents and young adults is beneficial for the differential diagnosis between JCT and other diseases involving hypertension. This study provides several conclusions drawn from our analysis that facilitate our understanding of JCT. JCT more often presents in patients aged 14 to 30 years. Patients in this age range with grade 3 hypertension (systolic or diastolic pressure) and/or moderate hypokalemia (2.5–3.0 mmol/L) are more likely to have JCT than ccRCC if they are found to have a renal tumor, unless adrenal diseases or renal artery stenoses are present. Characteristic MRI findings are also helpful for JCT diagnosis.

Disclosures

All authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues Chongchong Wu and Ruiping Chang for their help in this study.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:982–990. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12810. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Robertson PW, Klidjian A, Harding LK, et al. Hypertension due to a renin‐secreting renal tumour. Am J Med. 1967;43:963–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ørjavik OS, Fauchald P, Hovig T, et al. Renin‐secreting renal tumour with severe hypertension. Case report with tumour renin analysis, histopathological and ultrastructural studies. Acta Med Scand. 1975;197:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Conn JW, Cohen EL, McDonald WJ, et al. Hypertension, hyperreninemia and secondary aldosteronism due to rennin producing juxtaglomerular cell tumor. Arch Intern Med. 1972;13:682–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McVicar M, Carman C, Chandra M, et al. Hypertension secondary to renin‐secreting juxtaglomerular cell tumor: case report and review of 38 cases. Pediatr Nephrol. 1993;7:404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osawa S, Hosokawa Y, Soda T, et al. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor that was preoperatively diagnosed using selective renal venous sampling. Intern Med. 2013;52:1937–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuroda N, Gotoda H, Ohe C, et al. Review of juxtaglomerular cell tumor with focus on pathobiological aspect. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dong D, Li H, Yan W, Xu W. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor of the kidney–a new classification scheme. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim HJ, Kim CH, Choi YJ, et al. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor of kidney with CD34 and CD117 immunoreactivity: report of 5 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanabe A, Naruse M, Ogawa T, et al. Dynamic computer tomography is useful in the differential diagnosis of juxtaglomerular cell tumor and renal cell carcinoma. Hypertens Res. 2001;24:331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hollifield JW, Page DL, Smith C, et al. Renin‐secreting clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:859–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keehn CA, Pow‐Sang JM, Ahmad N. Pathologic quiz case: a 57‐year‐old man with hypertension and hypokalemia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:495–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Endoh Y, Motoyama T, Hayami S, Kihara I. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor of the kidney: report of a non‐functioning variant. Pathol Int. 1997;47:393–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sakata R, Shimoyamada H, Yanagisawa M, et al. Nonfunctioning juxtaglomerular cell tumor. Case Rep Pathol. 2013;2013:973865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gross BA, Mindea SA, Pick AJ, et al. Diagnostic approach to Cushing disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wong L, Hsu TH, Perlroth MG, et al. Reninoma: case report and literature review. J Hypertens. 2008;26:368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60:615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weikert S, Ljungberg B. Contemporary epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma: perspectives of primary prevention. World J Urol. 2010;28:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reuter VE. The pathology of renal epithelial neoplasms. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu L. Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension (Chinese). Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011;8:579–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eliacik E, Yildirim T, Sahin U, et al. Potassium abnormalities in current clinical practice: frequency, causes, severity and management. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors: Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004:72–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haab F, Duclos JM, Guyenne T, et al. Renin secreting tumors: diagnosis, conservative surgical approach and long‐term results. J Urol. 1995;153:1781–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin SA, Mynderse LA, Lager DJ, Cheville JC. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:854–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brandal P, Busund LT, Heim S. Chromosome abnormalities in juxtaglomerular cell tumors. Cancer. 2005;104:504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Segers P, Rietzschel E, Heireman S, et al. Carotid tonometry versus synthesized aorta pressure waves for the estimation of central systolic blood pressure and augmentation index. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1168–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aggoun Y, Farpour‐Lambert NJ, Marchand LM, et al. Impaired endothelial and smooth muscle functions and arterial stiffness appear before puberty in obese children and are associated with elevated ambulatory blood pressure. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:792–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arumugam S, Sreedhar R, Thandavarayan RA, et al. Angiotensin receptor blockers: focus on cardiac and renal injury. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016;26:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. López G‐Asenjo JA, Blanco González J, Ortega Medina L, Sanz Esponera J. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor of the kidney. Morphological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies of a new case. Pathol Res Pract. 1991;187:354–359; discussion 360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abbi RK, McVicar M, Teichberg S, et al. Pathologic characterization of a renin‐secreting juxtaglomerular cell tumor in a child and review of the pediatric literature. Pediatr Pathol. 1993;13:443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gennari FJ. Pathophysiology of metabolic alkalosis: a new classification based on the centrality of stimulated collecting duct ion transport. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:626–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Keton TK, Campbell WB. The pharmacologic alteration of renin release. Pharmacol Rev. 1981;32:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]