Abstract

Thirty patients who underwent percutaneous renal denervation, which was performed by a single operator following the standard technique, were enrolled in this study. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 2 (n=19), 3 (n=6), and 4 (n=5) were included. Data were obtained at baseline and at monthly intervals for the first 6 months. At 7 months, follow‐up data were collected bimonthly until month 12, after which data were collected on a quarterly basis. Baseline blood pressure values (mean±standard deviation) were 185±18/107±13 mm Hg in the office and 152±17/93±11 mm Hg through 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). Three patients with stage 4 CKD required chronic renal replacement therapy (one at the 13‐month follow‐up and two at the 14‐month follow‐up) after episodes of acute renal injury; their follow‐up was subsequently discontinued. The office blood pressure values at the 24‐month follow‐up were 131±15/87±9 mm Hg (P<.0001, for both comparisons); the corresponding ABPM values were 132±14/84±12 mm Hg (P<.0001, for both comparisons). The mean estimated glomerular filtration rate increased from 61.9±23.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 to 88.0±39.8 mL/min/1.73 m2 (P<.0001). The urine albumin:creatinine ratio decreased from 99.8 mg/g (interquartile range, 38.0–192.1) to 11.0 mg/g (interquartile range, 4.1–28.1; P<.0001 mg/g). At the end of the follow‐up period, 21 patients (70% of the initial sample) were no longer classified as having CKD.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major public health challenge worldwide. The major consequences of CKD include progressive loss of kidney function leading to end‐stage renal disease (ESRD), accelerated cardiovascular disease (CVD), and eventually death. In 2011, the number of patients with ESRD in the United Sates reached 615,899, a new high.1, 2

Hypertension is both a common cause and a major consequence of CKD. Blood pressure (BP) control is more difficult in the presence of CKD, as noted by the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP), which showed that only 13.2% of patients maintained BP control.3 The pathophysiology of hypertension in CKD presents several clinical dilemmas, such as reduced ability to excrete salt and water. Both the afferent and efferent renal sympathetic nerves are crucial for the onset and continuation of hypertension. Sympathetic hyperactivity occurs early in the course of CKD and increases significantly with the progression to ESRD.4, 5, 6, 7 Adequate BP control is known to reduce the rate of CKD progression. However, renal sympathetic denervation (RSD) has recently emerged as a powerful tool for controlling refractory hypertension.8, 9 Moreover, substantial evidence from experimental studies has shown that renal denervation may reduce CKD progression.10, 11, 12, 13 This finding suggests a promising benefit to patients with CKD and refractory hypertension. In addition, in two studies with a short follow‐up period, RSD was associated with a postprocedure increase in glomerular filtration14, 15, 16 and a reduction in albuminuria.14, 15, 17

This study is the first to perform a long‐term analysis of the effects of percutaneous RSD on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albumin excretion in patients with CKD and refractory hypertension.

Methods

This study was a prospective, longitudinal investigation of patients with CKD at stages 2, 3, and 4 and refractory hypertension who underwent transcatheter renal sympathetic artery denervation. The study was approved by the Committee of Ethics in Research of the Medical School of Universidade Federal Fluminense, and all patients signed informed consent forms.

Study Patients

We report a 24‐month follow‐up evaluation of a group of patients who underwent successful RSD from June 2011 to December 2012. The study was conducted in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, as a partnership between Universidade Federal Fluminense and the Hospital Regional Darcy Vargas.7 Patients were recruited from the university hospital and the public health network of the county. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) systolic BP ≥160 mm Hg (or ≥150 mm Hg for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus), with confirmation using multiple measurements while in the office, despite treatment with nonpharmacologic therapies and the use of at least three antihypertensive medications (including a diuretic) at the maximum doses or confirmed intolerance for medications; (2) GFR estimated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD‐EPI) equation18 between 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 (patients with eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were required to have microalbuminuria); and (3) age from 18 to 70 years.

Exclusion criteria included pregnancy; valvular heart disease with significant hemodynamic consequences; use of warfarin; stenotic valvular heart disease; acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, or transient ischaemic attack within the previous 6 months; renovascular anomalies (including renal artery stenosis, angioplasty with or without stenting, or double or multiple main arteries in the same kidney); and diabetes mellitus type 1 or other secondary causes of hypertension.

All patients involved in this study were treated for hypertension for at least 1 year prior to enrolment. Baseline medications were unchanged for at least 3 months before renal nerve ablation.

Study Procedures and Assessment

Patients underwent a complete medical history and physical examination. Hypertension was diagnosed on the basis of the current Brazilian Society of Cardiology guidelines and the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension.19, 20 Patients were screened for other secondary types of hypertension according to current guidelines.19, 20 BP measurements were performed in both arms with the patients in the standing, sitting, and supine positions during at least two subsequent visits. Patients also underwent screening blood testing for complete blood cell count and biochemistry (including serum creatinine levels to estimate GFR). Urine samples were obtained to measure albuminuria, protein, and creatinine levels. Twenty‐four–hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) was used to rule out pseudoresistant hypertension. We also evaluated BP levels during periods of wake and sleep and performed echo Doppler evaluation of the anatomy of the renal arteries.

Baseline medications were unchanged for at least 3 months prior to renal nerve ablation to avoid bias in the results, and treatment was maintained at follow‐up. The patients were instructed not to change medications or dosages after the procedure unless clinically indicated. The drug records and adherence for each patient were comprehensively reviewed and documented at each visit.

All of the patients received intravenous sodium bicarbonate (3 mL/kg) and 0.9% saline for 1 hour as prophylaxis for the attenuation of iodinated contrast media–associated nephrotoxicity.21, 22

Patients were pretreated with diazepam or midazolam by an anesthesiologist. Catheterization of the femoral artery by the standard Seldinger technique was performed after subcutaneous injection of local anesthetic in the inguinal region. An 8‐Fr valve sheath was introduced into the artery, and unfractionated heparin was administered as an intravenous bolus; the target activated coagulation time (ACT) was 0.250 seconds in the first 10 minutes. During the procedure, the target ACT range was 250 to 350 seconds. Subsequently, angiography of the aorta and renal arteries was performed using an 8‐Fr Balkin introducer, and a 7‐Fr irrigated ablation catheter was inserted (AlCath Flux eXtra Gold Full Circle 2708; VascoMed GmbH, Binzen, Germany) into the renal artery, allowing the delivery of radiofrequency (RF) energy to the renal artery innervation. The catheter was then irrigated, and the length of its gold‐tipped electrode was approximately four‐fold higher than the electrode length for the catheter traditionally used in this type of procedure. Because the application of RF is usually very painful, fentanyl was intravenously administered before the procedure. RF applications were performed within the main stem of the renal arteries, bilaterally; a series of RF pulses at 8 W power for a period of 60 seconds each were applied with an irrigation flow rate of 17 mL/min and an aim of >4 RF applications per renal artery, depending on their length. The points were ablated with at least 5 mm between them, and the catheter was moved from the distal to the proximal renal artery in a circumferential manner. The number of lesions per artery was chosen based on the artery length, which was measured by angiography. For arteries shorter than 20 mm, a minimum of four lesions was applied, and for every arterial length increase of 5 mm, one additional lesion was provided. After the procedure, the anatomy of the renal arteries was reviewed by angiography to assess whether there were any complications during the procedure. At the end of the procedure, patients received another infusion of sodium bicarbonate (1 mL/kg/h) for 6 hours.21, 22

After the procedure, patients remained hospitalized for a period of 24 hours in an inpatient ward. Follow‐up was performed weekly for the first month, monthly from the second to the sixth months, bimonthly from the seventh to the 12th months, and quarterly during the second year. At each follow‐up office visit, after the patient stood for 10 minutes, BP was measured in both upper limbs while the patient was in sitting and supine positions; the mean of all four extremities was recorded. Measurements were separated by at least 5 minutes after each position change (standing, sitting, and supine). Blood and urine samples were collected to monitor the laboratory variables at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after the procedure. ABPM was performed at the first, third, sixth, 12th, and 24th months after the procedure to evaluate the BP control and the effectiveness of RSD. Echo Doppler was also performed to evaluate the anatomy of the renal arteries of the patients at the first and sixth months after the RSD. The following variables were monitored during the follow‐up period: systolic and diastolic BP, number and doses of antihypertensive medications, eGFR, and albuminuria.

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as the mean and standard deviation in the case of a normal distribution and as the median and interquartile range otherwise. All statistical tests were two‐sided. Comparisons between two‐paired values were performed by the paired t test with a Gaussian distribution or, alternatively, by the Wilcoxon test. Comparisons between more than two values were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures or using Kruskal‐Wallis ANOVA as indicated and complemented by a post hoc test. Frequencies were compared with the χ 2 test. P values <.05 were considered significant. The following correlations between two variables were calculated: Pearson correlations in the case of a Gaussian distribution or alternatively, Spearman's correlations. All statistical analysis was performed using the program GraphPad Prism v 5.0 (GraphPad software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

Of the 33 initially selected patients, three were excluded because of vascular anomalies that contraindicated RSD. Table 1 provides the general characteristics of the 30 enrolled patients. Nineteen of the 30 patients had stage 2 CKD, six had stage 3, and five had stage 4. Eleven patients had type 2 diabetes mellitus. The mean systolic/diastolic arterial pressure was 185±18/107±13 mm Hg and patients were taking an average of 4.6±1.4 different classes of antihypertensive drugs.

Table 1.

General Features of Patients at Baseline

| No. | 30 |

| Age, y | 55±10 |

| Female sex | 17 (57) |

| Ethnicity (nonwhite) | 21 (70) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.8±4.9 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (17) |

| Stroke | 6 (20) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 11 (37) |

| Antihypertensives, No. | 4.6±1.4 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m² (CKD‐EPI) | 61.9±23.9 |

| CKD stage | |

| 2 | 19 (63) |

| 3 | 6 (20) |

| 4 | 5 (17) |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | 185±18/107±13 |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CKD‐EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. Values are expressed as number (percentage) or mean±standard deviation.

Ablation Procedure

In this patient cohort, 463 ablation lesions were performed. The average number of lesions delivered was 9±3 (range, 4–14) in the right renal artery and 9±3 (range, 5–14) in the left renal artery. The mean duration of ablation was 1060±357 seconds per patient (range, 600–1680 seconds), the duration of the procedure ranged from 30 to 60 minutes, and the mean exposure time to fluoroscopy was 21±6 minutes.

Follow‐Up

Of the 30 patients who started the study, 27 patients completed the 24 months of follow‐up, and three patients required chronic renal replacement therapy. One patient initiated dialysis at the 13th month of follow‐up after an acute renal insult associated with pulmonary sepsis. The other two started dialysis at the 14th month, also after acute renal injury episodes: one related to a perforated gastric ulcer and the other following decompensation of heart failure and lung infection. For these three patients, the presented data were collected until their last follow‐up visit at 12 months. After these patients began hemodialysis, they were excluded from the study and their eGFR values were considered zero at 18 and 24 months.

Efficacy in BP Reduction

All patients undergoing ablation of renal arteries showed a highly significant reduction in both systolic and diastolic BP measured at each office visit after the procedure. Accordingly, the BP decreased from 185±18/107±13 to 138±13/89±10, 139±14/91±9, 137±14/89±8, 132±15/86±9, 131±15/87±9, and 131±15/87±9 mm Hg at months 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, respectively (P<.0001 for systolic and diastolic values at every instance vs baseline).

The reduction in the average values of systolic and diastolic BP was also significant for the 24‐hour ABPM values at months 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after the procedure, with a reduction from 152±17/93±11 to 135±13/84±9, 134±13/85±9, 134±14/86±11, 133±14/85±10, and 132±14/84±12 mm Hg, respectively (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Changes in Antihypertensive Medications After the Procedure

The average number of antihypertensive drugs used per patient when evaluated at the 24th month after ablation (3.2±1.3) was reduced compared with baseline (4.6±1.3) (P<.0001). No patient required a greater number of antihypertensive medications. In the majority of patients, the number or dosage of medications decreased (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medication Use by Class During the Study

| Type of Antihypertensive Agent | Baseline (n=30) | 24th Month (n=27) |

|---|---|---|

| Diuretic | 30 (100) | 21 (78) |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 3 (10) | 2 (7) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 25 (83) | 18 (67) |

| ACE inhibitor | 5 (17) | 2 (7) |

| Direct renin inhibitor | 3 (10) | 2 (7) |

| β‐Blocker | 24 (80) | 19 (70) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 28 (93) | 19 (70) |

| Centrally acting sympatholytic | 11 (37) | 5 (19) |

| Vasodilator | 4 (13) | 0 (0) |

| α1‐Adrenergic blocker | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviation: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme. Values are expressed as number (percentage).

Renal Function

The median albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) at the first month of follow‐up was not significantly different from that at baseline. However, at the third month, the median ACR value was significantly lower than that at baseline, and this decrease was sustained until the 24th month after the procedure, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

ACR and Plasma Creatinine Level at Baseline and Throughout the Follow‐Up

| Baseline (n=30) | First Month (n=30) | Third Month (n=30) | Sixth Month (n=30) | 12th Month (n=30) | 18th Month (n=27) | 24th Month (n=27) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR, mg/g | 99.8 (38.0–192.1) | 46.9 (19.0–182.3) | 23.9a (10.9–159.8) | 24.4b (10.7–96.3) | 17.9c (10.0–100.6) | 15.2c (8.4–86.1) | 11.0d (4.1–28.1) |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.46±0.95 | 1.25±0.93c | 1.25±0.95c | 1.21±0.89d | 1.12±0.95d | 0.93±0.58d | 0.81±0.57d |

Abbreviation: ACR, albumin:creatinine ratio. Values are expressed as median (interquartile range) or mean±standard deviation. a P<.05. b P<.01. c P<.001. d P<.0001 (all vs corresponding baseline values).

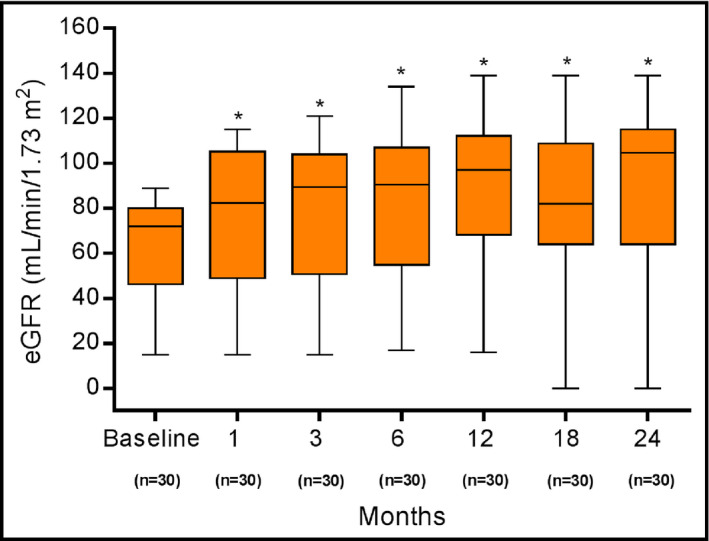

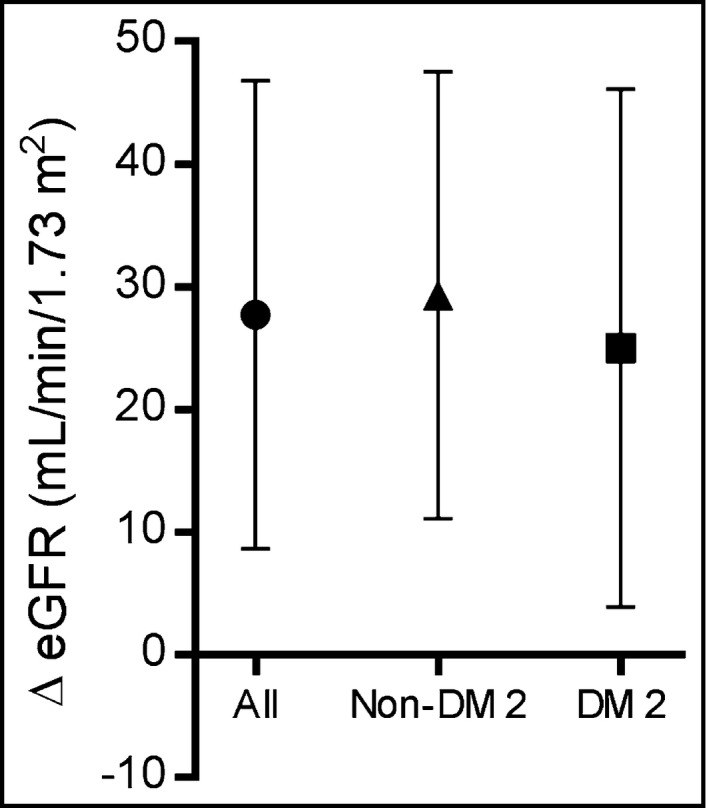

At all months of follow‐up after the RSD, the serum creatinine levels decreased significantly from baseline (Table 3). As a consequence, a significant increase in eGFR was observed from baseline (61.9±23.9 mL/min/1.73 m2) to follow‐up at month 1 (76.1±32.5 mL/min/1.73 m2, P<.0001), month 3 (77.2±33.2 mL/min/1.73 m2, P<.0001), month 6 (80.3±35.0 mL/min/1.73 m2, P<.0001), month 12 (86.1±35.2 mL/min/1.73 m2, P<.0001), month 18 (79.1±37.7 mL/min/1.73 m2, P<.0001), and month 24 (88.0±39.8 mL/min/1.73 m2, P<.0001) (Figure 1). The variation (∆) in the eGFR between month 24 after RSD and baseline did not differ when all patients (∆=27.7±19.1 mL/min/1.73 m2), patients without type 2 diabetes (∆=29.3±18.2 mL/min/1.73 m2), and patients with type 2 diabetes (∆=25.0±21.1 mL/min/1.73 m2) were compared (P>.05 for all comparisons) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at baseline and at months 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 after renal denervation. Values are presented as mean±standard deviation. *P<.0001 vs corresponding baseline values. At months 18 and 24, patients who required chronic renal replacement therapy (n=3) were assigned an eGFR value of 0.

Figure 2.

Mean increase (∆) and standard deviation of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at month 24 of the follow‐up period after renal denervation: all patients (circles, n=30), nondiabetic patients (triangles, n=19), and type 2 diabetic patients (squares, n=11). The final values used for the calculation were the ones collected at month 24 for those who completed the study period (n=27). Patients who required chronic renal replacement therapy (n=3) were included with an eGFR value of 0. DM 2 indicates type 2 diabetes mellitus.

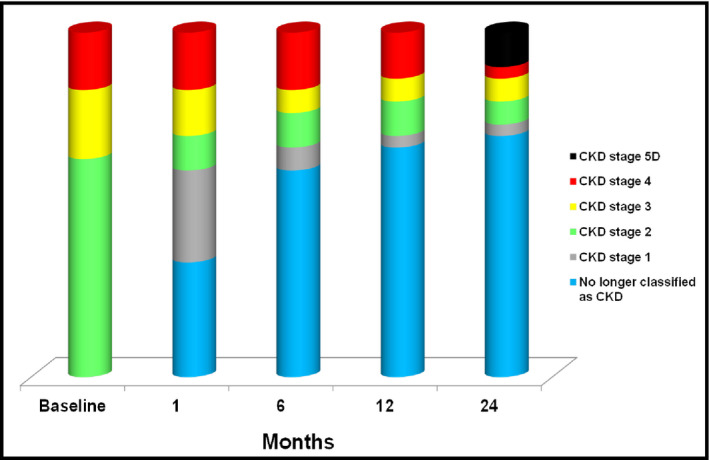

The distribution of CKD severity also improved after the procedure (Figure 3). Before RSD, all patients had a CKD stage of 2 to 4, with a higher percentage (63%) in stage 2. At the end of month 24, three patients (10%) were classified as having stage 5D (CKD on dialysis), but 21 (70%) could no longer be considered as having CKD because their eGFR was higher than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and their ACR was lower than 30 mg/g.

Figure 3.

Stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) at baseline and at months 1, 6, 12, and 24 after renal denervation (n=30). CKD stage 5D, chronic kidney disease on dialysis.

Safety

Of the 30 patients who underwent RSD, only one patient had bleeding at the puncture site of the femoral artery immediately after the procedure; this bleeding was adequately managed by mechanical compression, fluid infusion, and blood transfusion. Real‐time renal artery imaging was performed to assess internal structural changes related to the procedure. Several small focal irregularities of the renal arteries that were present during the procedure (possibly due to minor spasm or edema) were no longer observed postoperatively. At months 1 and 6 after ablation, all patients underwent a Doppler scan of the renal arteries, which showed no evidence of stenosis or flow limitation.

Discussion

In this prospective clinical study, we performed a long‐term follow‐up of CKD patients with refractory hypertension who were successfully treated by RSD.14, 15 Similar to previous studies of non‐CKD populations,23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 the present study of patients with refractory hypertension and CKD showed that RSD led to a marked and sustained reduction in systolic and diastolic BPs, both in the office and as indicated by 24‐hour ABPM.

To our knowledge, the present series is the largest and only study in the literature with 2 years of follow‐up to evaluate percutaneous renal artery denervation in CKD patients with refractory hypertension. In this study, our main objective was to analyze the temporal changes in renal function after RSD. This prospective analysis compared individual baseline variables with postoperative variables, making the analysis less prone to bias. We enrolled patients with refractory hypertension and CKD stages 2 (63%), 3 (20%), and 4 (17%). We used eGFR to accurately assess renal function, which is the standard of care in the clinical evaluation of glomerular filtration. We calculated eGFR using the CKD‐EPI equation, which is known to perform better for a larger range of GFR values.18 The adopted protocol14, 15 for denervation involved the delivery of a higher number of ablative lesions per artery than in previous studies8, 9 and an irrigated catheter that had more extensive surface contact. Recent data suggest that the combined number of complete and incomplete ablation runs (ie, overall number of ablation attempts) is associated with greater BP reductions.30 A significant correlation was found between the decrease in office systolic BP at 1 year after the RSD and the total number of ablation lesions.31 A recent analysis confirmed that denervation is often incomplete and surprisingly nonuniform from patient to patient,30, 32 which seems to be the case in a recent very well‐designed study that had disappointing results.33

In the present study, RSD did more than simply delay the progression of CKD. Following RSD, patients exhibited an early and progressive increase in eGFR. At the end of the first month, a mean increase in eGFR of 23% was observed; at 24 months after RSD, this improvement was increased to 42%. The ACR gradually decreased over time, with a 53% decrease in ACR noted at the first month and an 87% decrease found at the end of the 24‐month follow‐up period. We have already reported the increase in eGFR in our sample after 6 months and 1 year of follow‐up14, 15, 32 as a unique finding in the literature. We now show that this increase is sustained at the end of 2 years after RSD. Our data apparently contrast with a recent study of patients with CKD in which the observed eGFR did not change 12 months after the procedure.34 However, the two patient populations differ substantially. The majority of our patients were classified as having CKD stage 2 (eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2), in contrast to the previous study whose patients had an eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

No previous study has reported such encouraging results. In agreement with our results, a recent study reported an ACR reduction in patients with refractory hypertension and albuminuria following RSD.17 Albuminuria is a well‐known independent cardiovascular risk factor,35 making it likely that our patients may experience benefits beyond the correction of their renal impairment. Recently, Ott and colleagues36 conducted an observational pilot study of 27 patients with CKD stages 3 and 4 and reported that the RSD treatment of hypertension decreased BP and augmented eGFR by +1.5±10 mL/min/1.73 m2, halting the decline in renal function. Consistent with our findings, unpublished data from the Adelaide and Renal EnligHTN Blood Flow study, which was presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2014, showed increased eGFR and a reduction in the levels of urinary protein excretion and plasma aldosterone in refractory hypertension patients with eGFR ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m2 6 months after renal denervation.16

Increased sympathetic tone, a well‐known risk factor for CVD, is also frequently present in patients with essential hypertension and in those with CKD.37, 38, 39 In both hypertension and renal failure, the mechanisms of the hyperadrenergic state are manifold and include reflex and neurohumoral pathways.4, 37, 38 In CKD, sympathetic overactivity occurs early in the course of the disease and shows a direct relationship with the severity of renal failure.4, 5, 6, 7 Increased sympathetic tone can perturb renal function, thus inducing sodium retention, increased blood volume, a reduction in renal blood flow, and activation of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system.40 A number of studies have shown that impaired renal function is an independent cardiovascular risk factor,7, 37, 38, 41, 42 and the associated hyperadrenergic state is one possible pathway in the high cardiovascular mortality seen in these patients.

The distribution of CKD severities also improved substantially after RSD. Before the procedure, the majority of the CKD patients were categorized as having stage 2 CKD. At the end of the follow‐up period, three of the patients (10%) with stage 4 CKD prior to RSD required dialysis after 1 year of follow‐up after each experienced an episode of acute kidney injury. At the end of the 24‐month follow‐up, 21 patients (70%) no longer met the criteria for CKD classification and had eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and ACR <30 mg/g; this finding has never been reported in studies of interventions for delaying CKD progression.

Notably, muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) was reported to be significantly higher in hypertensive patients with mild renal insufficiency than in hypertensive patients with normal renal function and in normotensive patients.43 Similarly, a recent study also evaluated MSNA and reported a substantial and rapid reduction in the firing properties of single sympathetic vasoconstrictor fibers 3 months after RSD in patients with refractory hypertension.44 The interruption of this sympathetic hyperactivity may, at least in part, explain our results. The attenuation of other pathways that are potentially harmful to the kidneys, such as the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system,45 could also account for our findings. Finally, our findings may represent the first clinical corollary to experimental studies in which renal denervation and/or blockage of adrenergic receptors were found to delay CKD progression in different models of kidney disease. Attenuation of the inflammatory cascade that causes interstitial fibrosis and a reduction of glomerular filtration have been demonstrated in models of ureteral obstruction46 and renal ischemia and reperfusion injury.10 In addition, structural kidney preservation and reduced albumin excretion were demonstrated in an experimental model of immune glomerulonephritis11 and following blockage of adrenergic receptors after unilateral nephrectomy.12, 13

Study Limitations

The relatively small sample is a limitation of this study. However, the present series is the largest in the literature to address percutaneous renal artery denervation in CKD patients and it has the longest follow‐up. However, given that the study is uncontrolled, our findings should be interpreted with caution. In addition, more precise methods of assessing GFR, such as cystatin C or iothalamate, should be used in future studies to confirm our findings regarding the effects of RSD on the GFR. The use of only one serum creatinine measurement at each time point of the study should also be considered.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that RSD in patients with resistant hypertension and CKD provided both a significant reduction in BP and a substantial reduction in the number of antihypertensive drugs. More importantly, RSD was associated with a long‐term increase in eGFR and decrease in albumin excretion, thus curing patients with early‐stage CKD. Although encouraging, our data are preliminary and must be validated in a larger population.

Funding

This study was supported by the program of development at the Hospital Regional Darcy Vargas.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants in this study. The author Márcio Kiuchi is especially grateful to Professor Murray Esler for his intellectual support.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:190–196. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12724. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Collins AJ, Foley RN, Chavers B, et al. US Renal Data System 2012 annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end‐stage renal disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(suppl 1):A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: approaches and initiatives—a position statement from kidney disease improving global outcomes. Kidney Int. 2007;72:247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sarafidis PA, Li S, Chen SC, et al. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2008;121:332–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGrath BP, Ledingham JG, Benedict CR. Catecholamines in peripheral venous plasma in patients on chronic haemodialysis. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1978;55:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schlaich MP, Socratous F, Hennebry S, et al. Sympathetic activation in chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:933–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neumann J, Ligtenberg G, Klein II, et al. Sympathetic hyperactivity in chronic kidney disease: pathogenesis, clinical relevance, and treatment. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1568–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grassi G, Bertoli S, Seravalle G. Sympathetic nervous system: role in hypertension and in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krum H, Schlaich MP, Sobotka PA, et al. Percutaneous renal denervation in patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension: final 3‐year report of the Symplicity HTN‐1 study. Lancet. 2014;383:622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Symplicity HTN‐2 Investigators , Esler MD, Krum H, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension (The Symplicity HTN‐2 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1903–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim J, Padanilam BJ. Renal denervation prevents long‐term sequelae of ischemic renal injury. Kidney Int. 2015;87:350–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Veelken R, Vogel EM, Hilgers K, et al. Autonomic renal denervation ameliorates experimental glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1371–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Amann K, Koch A, Hofstetter J, et al. Glomerulosclerosis and progression: effect of subantihypertensive doses of alpha and beta blockers. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1309–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amann K, Rump LC, Simonaviciene A, et al. Effects of low dose sympathetic inhibition on glomerulosclerosis and albuminuria in subtotally nephrectomized rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1469–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kiuchi MG, Maia GL, de Queiroz Carreira MA, et al. Effects of renal denervation with a standard irrigated cardiac ablation catheter on blood pressure and renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease and resistant hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2114–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kiuchi MG, Chen S, Andrea BR, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with hypertension and chronic kidney disease: does improvement in renal function follow blood pressure control? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:794–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Delacroix S, Chokka RG, Sahay S, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation increases renal artery blood flow: a serial MRI study in resistant hypertension. Abstract 18099. Data from Adelaide ENLIG‐HTN and RENAL BLOOD FLOW. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/130/Suppl_2/A18099.abstract?cited-by=yes&legid=circulationaha;130/Suppl_2/A18099. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- 17. Ott C, Mahfoud F, Schmid A, et al. Improvement of albuminuria after renal denervation. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173:311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sociedade Brasileira de. Cardiologia, Sociedade Brasileira de Hipertensão, Sociedade Brasileira de Nefrologia . VI Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Merten GJ, Burgess WP, Rittase RA, Kennedy TP. Prevention of contrast‐induced nephropathy with sodium bicarbonate: an evidence‐based protocol. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2004;3:138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. ten Dam MA, Wetzels JF. Toxicity of contrast media: an update. Neth J Med. 2008;66:416–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krum H, Schlaich M, Whitbourn R, et al. Catheter‐based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: a multicentre safety and proof‐of‐principle cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373:1275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Symplicity HTN‐1 Investigators . Catheter‐based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: durability of blood pressure reduction out to 24 months. Hypertension. 2011;57:911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pokushalov E, Romanov A, Corbucci G, et al. A randomized comparison of pulmonary vein isolation with versus without concomitant renal artery denervation in patients with refractory symptomatic atrial fibrillation and resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azizi M, Sapoval M, Gosse P, et al. The Renal Denervation for Hypertension (DENERHTN) investigators. Optimum and stepped care standardised antihypertensive treatment with or without renal denervation for resistant hypertension (DENERHTN): a multicentre, open‐label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1957–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mahfoud F, Ukena C, Schmieder RE, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure changes after renal sympathetic denervation in patients with resistant hypertension. Circulation. 2013;128:132–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zuern CS, Rizas KD, Eick C, et al. Effects of renal sympathetic denervation on 24‐hour Blood Pressure Variability. Front Physiol. 2012;3:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Voskuil M, Verloop WL, Blankestijn PJ, et al. Percutaneous renal denervation for the treatment of resistant essential hypertension; the first Dutch experience. Neth Heart J. 2011;19:319–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kandzari DE, Bhatt DL, Brar S, et al. Predictors of blood pressure response in the SYMPLICITY HTN‐3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kiuchi MG, Chen S, Graciano ML, et al. Acute effect of renal sympathetic denervation on blood pressure in refractory hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease. Int J Cardiol. 2015;190:29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Esler M. Renal denervation for treatment of drug‐resistant hypertension. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O'Neill WW, et al. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hering D, Mahfoud F, Walton AS, et al. Renal denervation in moderate to severe CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmieder RE, Mann JF, Schumacher H, et al. Changes in albuminuria predict mortality and morbidity in patients with vascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1353–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ott C, Mahfoud F, Schmid A, et al. Renal denervation preserves renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease and resistant hypertension. J Hypertens. 2015;33:1261–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grassi G. Sympathetic neural activity in hypertension and related diseases. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:1052–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grassi G. Assessment of sympathetic cardiovascular drive in human hypertension: achievements and perspectives. Hypertension. 2009;54:690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paton JF, Raizada MK. Neurogenic hypertension. Exp Physiol. 2010;95:569–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DiBona GF, Kopp UC. Neural control of renal function. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:75–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mahmoodi BK, Matsushita K, Woodward M, et al. Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end‐stage renal disease in individuals with and without hypertension: a meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2012;380:1649–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Parlongo S, et al. Plasma norepinephrine predicts survival and incident cardiovascular events in patients with end‐stage renal disease. Circulation. 2002;105:1354–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tinucci T, Abrahão SB, Santello JL, Mion D. Mild chronic renal insufficiency induces sympathetic overactivity. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hering D, Lambert EA, Marusic P, et al. Substantial reduction in single sympathetic nerve firing after renal denervation in patients with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61:457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang L, Lu CZ, Zhang X, et al.The effect of catheter based renal synthetic denervation on renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system in patients with resistant hypertension. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2013;41:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim J, Padanilam BJ. Renal nerves drive interstitial fibrogenesis in obstructive nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:229–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]