Abstract

Hypertension is a common and costly disease among US veterans. The Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system is the largest integrated healthcare provider in the United States and reviewing hypertension interventions developed in the VA may inform interventions delivered in other integrated healthcare systems. This review describes behavioral interventions to improve hypertension control that have been conducted in the VA since 1970. The authors identified 27 articles representing 15 behavioral interventional trials. Studies were heterogeneous across patients, providers, interventionist, and intervention components. The VA bridges services related to diagnosis, treatment, medication management, and behavioral counseling in a unified approach that supports collaboration and provides infrastructure for hypertension management.

In recent decades there has been improvement in hypertension care provided in the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system, the largest integrated healthcare provider in the United States. From 2000 to 2010, blood pressure (BP) control improved in the VA from 43.0% to 76.6%.1 There is a need for innovative behavioral approaches to continue and improve BP control. Reviewing hypertension interventions developed in the VA may inform interventions delivered in other systems. We performed a literature review describing behavioral hypertension interventions administered in the VA and distilled commonalities among successful programs. We emphasize behavioral management interventions because the success of BP control ultimately depends on a patient's willingness and ability to modify and maintain certain behaviors (eg, proper diet, exercise, and medication adherence). Therefore, our objective was not to report on VA hypertension care in general, but, rather, to focus on behavioral hypertension management interventions.

Methods

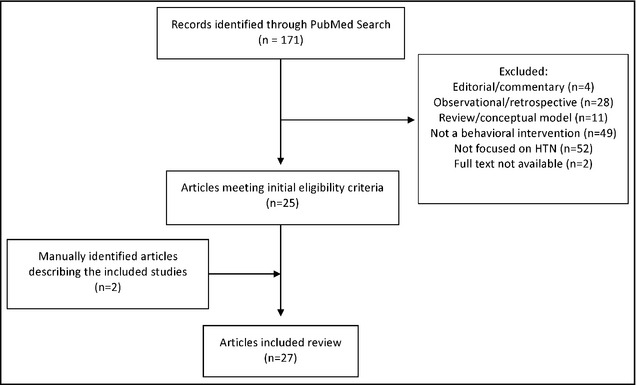

A literature search using the PubMed database was conducted. We identified articles containing MeSH and key words addressing intervention studies or clinical trials, veterans, and hypertension. Articles were limited to those published in English in the past 44 years. Studies need not be solely conducted in the VA. This initial search yielded 171 articles. We screened full articles for eligibility. Exclusion criteria included: (1) commentary or editorial; (2) observational or retrospective analysis; (3) review article or solely described a conceptual mode; (4) not focused on hypertension; or (5) not a patient‐focused behavioral hypertension intervention. The Figure outlines the article identification process. Interventions were divided into only behavioral or behavioral/medication management. We made this distinction because medication management interventions generally require complex design, necessitating the involvement and/or oversight of a clinician or pharmacist.

Figure 1.

Identification of included articles. The specific search strategy used was: ((((((“Hypertension “[Mesh] OR “hypertension” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“United States Department of Veterans Affairs” [Mesh] OR “Veterans” [Mesh] OR “Veterans Health” [Mesh] OR “Veterans” [Title/Abstract])) AND (“Intervention Studies” [Mesh] OR “Clinical Trial” [Publication Type]) AND English [lang])) AND (“1970/01/01”[PDat]: “2014/04/10”[PDat]))).

Results

We identified 27 articles representing 15 unique trials. Approximately 20% (n=3) of the interventions addressed patients and providers2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 80% (n=12) focused on patients solely.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 All studies included patient‐directed education; 60% (n=9) of the studies6, 7, 12, 14, 18, 19, 20, 23, 24, 25 also involved medication management.

Medication Management+Behavioral Components

A 6‐month, single‐site study was conducted to determine whether pharmaceutical care provided in a pharmacist‐managed hypertension clinic or in a traditional primary care setting resulted in better control of hypertension (Table 1).26 Individuals in the intervention group were scheduled for a clinical pharmacist visit once monthly. The pharmacist provided drug counseling, addressed recommended lifestyle changes and medication adherence, and made changes in drug selection and dosage as needed. Mean changes in systolic BP from baseline for the intervention and control groups were −18.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], −26.3 to −10.5) and −3.98 (95% CI, −11.8 to 3.79), respectively (P=.01). There was no significant difference in adherence between (P>.25) or within (P>.07) the two groups at baseline or at the end of the study.26

Table 1.

Summary of Published Studies Describing VA Hypertension Control Interventions That Use Medication Management±Behavioral Components

| Study Title | Lead Investigator (Primary Year) | Study Design | Sample Size | Setting | Arms | Intervention Content | Primary Study Outcome | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension Intervention Nurse Telemedicine Study (HINTS)12, 13, 17 | Bosworth (2011) | 4‐arm randomized controlled trial | 591 patients (147 usual care; 148 behavioral management; 149 medication management, 147 combined intervention) | Internal medicine clinics associated with the Durham VA Medical Center | Patients were randomized to a usual care control group or 1 of 3 telephone‐based intervention groups: nurse‐administered behavioral management; nurse‐ and physician‐administered medication management, or a combination of both | Wireless home BP monitoring; behavioral management intervention consisting of 11 tailored health behavioral models; medication management | Change in BP control measured at 6‐month intervals | 18 months |

| Veterans Affairs Multi‐disciplinary Education and Diabetes Intervention for Cardiac—Extended (MEDIC‐E)20 | Cohen (2011) | Randomized controlled trial | 99 patients (50 intervention; 49 usual care) | Providence VA Medical Center | Diabetic patients were randomized to a pharmacist‐led shared medication appointments program or standard primary care | 4 weekly group sessions followed by 5 monthly booster group sessions; each 2‐hour session included 1 hour of multidisciplinary diabetes‐specific healthy lifestyle education and 1 hour of pharmacotherapeutic intervention performed by a pharmacist | Hemoglobin A1c, LDL cholesterol, BP, diabetes self‐care behavior questionnaire | 6 months |

| N/A23 | Edelman (2010) | Randomized controlled trial | 239 patients were randomized (133 intervention group; 106 usual care group) | Three VA medical centers in North Carolina and Virginia | Patients were randomly assigned within each center to either attend GMCs or receive usual care | GMCs were comprised of 7 or 8 patients and a multidisciplinary care team. Groups met every 2 months (7 visits total). At each visit, BP was checked and home blood glucose values were collated. Patients attended an educational session delivered by the nurse or educator. Topics of the educational sessions were tailored to members' needs. The pharmacist and the primary care internist reviewed patient medical records, BPs, and home blood glucose readings during each session and developed individualized plans for medication or lifestyle management directed toward improving BP and hemoglobin A1c level. Sessions lasted 90 to 120 minutes | Outcomes were hemoglobin A1c level and systolic BP | 12 months |

| The Adherence and Intensification of Medications (AIM) study6, 7 | Heisler (2010) | Cluster‐randomized controlled effectiveness study | 4100 patients (1797 intervention; 2303 control) | Three VA facilities and 2 Kaiser Permanente Northern California facilities | Primary care teams within sites were randomized to a program led by a clinical pharmacist trained in motivational interviewing–based behavioral counseling approaches and authorized to make BP medication changes or to usual care | Motivational interviewing, medication management, behavioral change | Relative change in systolic BP measurements of time | 14 months |

| Improving BP in Colorado14 | Magid (2011) | Randomized controlled trial | 338 patients randomized; 283 completed the study (138 intervention; 145 usual care) | Three healthcare systems in Denver, Colorado, including a larger health maintenance organization, a VA medical center, and a county hospital | The multimodal intervention had 4 main components: patient education, home BP monitoring, home BP measurement reporting to an interactive voice response phone system, and clinical pharmacist management of hypertension with physician oversight | 3 or 4 weekly patient home‐based BP monitoring; clinical pharmacist review home BP values; medication management under preapproved drug therapy management protocols | Proportion of patients who achieved guideline‐recommended BP goals; change in systolic and diastolic BP between enrollment and 6‐month follow‐up visit | 6 months |

| N/A24 | Rifkin (2013) | Randomized, controlled clinical effectiveness trial | 43 patients (28 intervention; 15 usual care) | Chronic kidney disease and hypertension clinic at VA San Diego | Patients were randomized to use a novel telemonitoring device pairing a Bluetooth‐enabled BP cuff with an Internet‐enabled hub or to usual care | Patients were instructed to measure BP at home using study devices. If a participant had consistently above‐goal readings during the prior week, a study physician or pharmacist called to provide counseling or adjust medications as indicated. Additional in‐person follow‐up with clinic physicians or urgent care was scheduled at the discretion of the study team if it was felt that telephone counseling was not sufficient. Patients were also contacted if no readings were reported | Improvement in systolic BP at 6 months | 6 months |

| VA‐MEDIC25 | Taveira (2010) | Randomized controlled trial | 109 patients completed the study (58 intervention; 51 usual care) | VA medical center in Providence, Rhode Island | Patients received either: 4 weekly sessions of the VA‐MEDIC intervention in addition to usual care or usual care alone | VA‐MEDIC consisted of a 40‐ to 60‐minute educational component by nurse, nutritionist, physical therapist, or pharmacist followed by pharmacist‐led behavioral and pharmacologic interventions | Attainment of target goals in hemoglobin A1C, BP (systolic BP <130 mm Hg, diastolic BP <80 mm Hg), fasting lipids, and tobacco use | 1 month |

| N/A26 | Vivian (2002) | Randomized controlled trial | 56 patients (27 intervention; 29 usual care) | VA medical center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | The intervention arm participants were scheduled to meet monthly with a clinical pharmacist. Patients receiving usual care received standard care from their usual physician | The clinical pharmacist made appropriate changes in prescribed drugs, adjusted dosages, and provided drug counseling (eg, discussion of side effects, recommended lifestyle changes, assessment of compliance). | Changes in compliance, BP, and patient satisfaction | 6 months |

Abbreviations: –, not stated in the article; BP, blood pressure; GMCs, group medical clinics; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; N/A, not applicable; VA, Veterans Affairs.

The Improving Blood Pressure in Colorado (Colorado) study was a 6‐month multimodal intervention comprised of patient education, home‐based BP monitoring and reporting to an interactive voice‐response telephone system, and clinical pharmacist follow‐up.14 The intervention group was given an educational booklet and were trained in home monitoring and instructed to measure their BP three to four times weekly. Pharmacists provided counseling on lifestyle changes and made medication adjustments for those with poor BP control. BP reductions were greater in the intervention vs the usual care group (−13.1 mm Hg vs −7.1 mm Hg, P=.006 for systolic; −6.5 mm Hg vs −4.2 mm Hg, P=.07 for diastolic).14

Another intervention involving self‐monitoring and medication management was the Hypertension Intervention Nurse Telemedicine Study (HINTS). HINTS evaluated three telephone‐based interventions in a four‐group design: (1) nurse‐administered, behavioral management; (2) nurse‐administered, physician‐directed medication intervention using a validated clinical decision support system; (3) combined behavioral management and medication management intervention; and (4) usual care.12 All intervention patients were provided with a wireless home BP monitor and advised to monitor their BP daily. Both the behavioral management and medication management alone showed significant improvements at 12 months: 12.8% (95% CI, 1.6%–24.1%) and 12.5% (95% CI, 1.3%–23.6%), respectively. Improvements were not sustained at 18 months. In subgroup analyses, among those with poor baseline BP control, systolic BP decreased in the combined intervention group by 14.8 mm Hg (95% CI, −21.8 mm Hg to −7.8 mm Hg) at 12 months and 8.0 mm Hg (95% CI, −15.5 mm Hg to −0.5 mm Hg) at 18 months, relative to usual care.12

A single‐site, randomized, controlled device effectiveness study enrolled patients with stage 3 or higher chronic kidney disease and uncontrolled hypertension.24 Patients were randomized to usual care or a telemonitoring device pairing a Bluetooth‐enabled BP cuff with an Internet‐enabled hub, which wirelessly transmitted BP values. For the intervention group, patients were provided with a BP monitor and instructed to follow their physician's instructions regarding the frequency of monitoring. Patients were contacted if BP was above goal. Both groups had a significant improvement in systolic BP (P<.05). Systolic BP fell a median of 13 mm Hg in monitored participants compared with 8.5 mm Hg in usual care participants (P for comparison .31).24

The Adherence and Intensification of Medications (AIM) study was a cluster‐randomized controlled effectiveness study that also used a pharmacist interventionist.6 During a 14‐month period at five facilities, including two VA hospitals, primary care teams were randomized to either: (1) a program led by a clinical pharmacist trained in motivational interview–based behavioral approaches and authorized to make BP medication changes or (2) usual care. The mean systolic BP decrease from 6 months before to 6 months after the intervention period was 9 mm Hg in both arms. Mean systolic BP of eligible intervention patients were 2.4 mm Hg lower (95% CI, −3.4 to −1.5; P<.001) immediately after the intervention than those achieved by control patients.7

To evaluate the effectiveness of group medical clinics in the management of comorbid diabetes and hypertension, Edelman and colleagues23 conducted a two‐site randomized controlled trial. The group medical visits were comprised of seven to eight patients and a multidisciplinary care team. Groups met every 2 months. At each visit, BP was checked and home blood glucose values were collated. Patients attended an educational session delivered by the nurse or educator. Topics of the education sessions were tailored to members' needs. The pharmacist and the primary care internist reviewed patient medical records, BPs, and home blood glucose readings during each session and developed individualized plans for medication or lifestyle management directed toward improving BP and HbA1c level. Mean systolic BP improved by 13.7 mm Hg in the intervention group and 6.4 mm Hg in the usual care group (P=.011).23

The Veterans Affairs Multi‐disciplinary Education and Diabetes Intervention for Cardiac Risk Reduction (VA‐MEDIC) study evaluated whether a pharmacist‐led group medical visit program could improve achievement of target goals in hypertension and other goals among patients with type 2 diabetes compared with usual care.25 The program involved small‐group training sessions of four to eight participants lasting 40 to 60 minutes. A nurse, nutritionist, physical therapist, or pharmacist delivered the educational component, followed by pharmacist‐led behavioral and pharmacologic interventions, during 4 weekly sessions. After 4 months, a greater proportion of the intervention group participants were guideline adherent for BP levels compared with the usual care arm. A greater proportion of VA‐MEDIC participants vs controls achieved a systolic BP <130 mm Hg.25

The extended VA MEDIC‐E program20 involved diabetic patients randomly assigned to standard primary care or an intervention consisting of four weekly group sessions, followed by five monthly booster group sessions. Half of the session involved diabetes‐specific lifestyle education and half pharmacotherapeutic interventions performed by a clinical pharmacist. Educational topics, method of delivery, and teacher varied depending on the session. The booster intervention focused on group needs such as discussing options for exercising during inclement weather. After 6 months, the intervention group achieved target goals for HbA1c values (40.8% in cases vs 20.4% in usual care, P=.028) and systolic BP <130 mm Hg (58% cases vs 32.7% in usual care, P=.015).20

Behavioral Only

Brauer22 conducted a 6‐month study using relaxation therapy for improved BP (Table 2). The three arms included: (1) therapist‐conducted, face‐to‐face progressive, and deep‐muscle relaxation training; (2) progressive deep‐muscle relaxation therapy conducted mainly by home use of audiocassettes; or (3) nonspecific individual psychotherapy. After 6 months of postintervention follow‐up, the therapist‐conducted relaxation therapy group showed the greatest changes (−17.8 mm Hg systolic, −9.7 mm Hg diastolic).22

Table 2.

Summary of Published Studies Describing VA Hypertension Control Interventions That Use Behavioral Components

| Study Title | Lead Investigator (Primary Year) | Study Design | Sample Size | Setting | Arms | Intervention Content | Primary Study Outcome | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A21 | Bosley (1989) | 3‐arm randomized controlled trial | 41 patients (14 intervention; 27 control) | VA High BP Program | Three arms: Self‐Management Training (CSM), Attention Placebo Control, and Current Clinic Conditions Control | In the CSM group, the trainer presented information regarding the dynamics of stress and its role as a contributing factor in hypertension. Participants were trained to monitor their behavior in stressful experiences and be aware of their stress. | Coping style, psychological distress, and BP | – |

| Veterans Study to Improve the Control of Hypertension (V‐STITCH)3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12 | Bosworth (2005) | Randomized controlled health services intervention trial with split‐plot design |

30 primary care providers 588 patients (294 intervention; 294 control) |

Durham VA Medical Center Primary Care Clinic | Patient intervention included telephone contact by a nurse case manager every 2 months for 24 months | Telephone‐based nurse‐delivered information in nine educational and behavioral modules (for patients); audit and feedback of the provider's panel of patients with regards to guideline‐recommended BP targets and medication choices, and recommendations about management of patients' hypertension (for providers) | Proportion of patients who achieve a BP ≤140/90 mm Hg at each outpatient clinic visit over 24 months | 2 years |

| N/A22 | Brauer (1979) | Three‐arm single‐blind randomized controlled study | 29 patients (10 therapist‐conducted; 9 tape‐recorded; 10 control) | Palo Alto VA Hospital Outpatient Medical Clinic | Three arms: therapist‐conducted, face‐to‐face progressive, deep‐muscle relaxation training for 10 weekly sessions; progressive deep‐muscle relaxation therapy conducted mainly by home use of audiocassettes; nonspecific individual psychotherapy | Therapists then instructed patients thoroughly in relaxation techniques (eg, comfortable position, systematically tensing and relaxing muscles, breathing). Patients were instructed to practice the technique at home for 20 minutes daily, using a relaxation tape. They kept a record of their home practice, showing their progress and success in relaxing, particularly during identified stressful situations | Improvement in systolic and diastolic BP | 10 weeks |

| Posts Working for Veterans' Health (POWER)15, 16, 29, 31 | Mosack (2012) | Cluster randomized controlled trial | Randomized 113 volunteer leaders | 58 Veterans Service Organizations in Southeast Wisconsin | Compared two hypertension self‐management approaches: a peer‐led intervention that occurred in the context of monthly post meetings and an educational seminar intervention covering similar information in stand‐alone 90‐minute presentations by health professionals | Weighing, use of pedometers, and self‐monitoring through automated sphygmomanometers located at the posts | Improvement in systolic BP and hypertension knowledge, increased fruit/vegetable intake, and pedometer use | 12 months |

| N/A8, 9 | Roumie (2006) | Cluster randomized control trial |

182 providers (54 provider education only; 62 provider education and alert; 66 provider education, alert, and patient education); 1341 patients |

2 hospital‐based and 8 community‐based clinics in the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System | Providers were randomly assigned to receive either: (1) weekly educational e‐mails only; (2) weekly educational e‐mails plus patient‐specific alerts; or (3) both education and alerts plus their patients were sent an interventional letter | Provider education requested reevaluation of a patient's antihypertensive regimen; alerts were one‐time, patient‐specific notifications sent by the pharmacy to the provider through the electronic health record; the patient letter advocated drug adherence, lifestyle modification, and conversations with providers | Proportion of patients with systolic BP <140 mm Hg; intensification of antihypertensive medication | 6 months |

| N/A27 | Wakefield (2011) | 3‐arm randomized controlled efficacy trial | 302 patients (102 low‐intensity intervention; 93 high‐intensity intervention; 107 usual care) | Iowa City VA Medical Center |

Patients in the high‐intensity group had a device that used a branching disease management algorithm. The algorithm was programmed so that patients received both standard prompts each day and a rotation of questions and educational content. The low‐intensity group did not use the algorithm |

The intervention combined close surveillance via a home tele‐health device and nurse care management. Both intervention groups received care management from a study nurse | Primary outcomes were hemoglobin A1c and systolic BP; secondary outcome was adherence. Outcomes were measured at the end of the intervention (6 months) and again at 12 months to assess maintenance | 6 months |

Abbreviations: –, not stated in the article; BP, blood pressure; N/A, not applicable; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Bosley and Allen21 examined the use of coping skill–building to reduce BP levels. Patients were randomized to receive either: (1) cognitive self‐management training (CSM); (2) attention placebo control; or (3) current clinic conditions control. Participants in the CSM and attention placebo groups met for eight weekly 45‐minute sessions in groups of three to six members. In the CSM group, participants were trained to monitor their behavior in stressful experiences, to become aware of their bodies' reactions, and the negative self‐talk that occurred in such situations. Participants in the third group received only regular clinic care. The authors found a positive association between training and reduction of systolic BP.21

The Veterans' Study to Improve the Control of Hypertension (V‐STITCH) trial was a 2‐year health services intervention.4 Primary care providers at one North Carolina–based clinic (n=30) were randomized to an intervention or control group. Intervention providers received a patient‐specific electronically generated hypertension decision support system delivering guideline‐based recommendations at each visit. Patients whose providers were in this group were randomly assigned to receive a telephone‐administered intervention or usual care. The patient‐level intervention involved needs assessment, followed by tailored behavioral and education models to promote medication adherence and improve specific health behaviors.4 Rates of BP control for all patients receiving the patient behavioral intervention improved from 40.1% to 54.4% at 24 months (P=.03); patients in the nonbehavioral intervention group improved from 38.2% to 43.9% (P=.38).

Roumie and colleagues8, 9 conducted a cluster‐randomized trial to examine effectiveness of three quality improvement interventions of increasing intensity in improving veterans' BP control. Randomization occurred at the provider level; providers were randomized to one of three groups: (1) education, (2) education and alert, and (3) education and alert plus patient education. Educational information was delivered to providers via e‐mail with a Web‐based link to guidelines.28 For providers in the alert‐receiving arm, one‐time, patient‐specific, electronic alerts were sent by the pharmacy to the prescribing provider via the patient's electronic medical record during a 1‐week period. For the third arm, a personalized letter was sent to patients containing educational information and recommended use of behavioral strategies to improve BP control. Patients of providers who were randomly assigned to the patient education group had better BP control (138/75 mm Hg) compared with those in the provider education and alert or provider education alone groups (146/76 mm Hg and 145/78 mm Hg, respectively).8

Wakefield27 conducted a single‐site, randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of a nurse‐management home tele‐health and remote monitoring intervention to improve outcomes among veteran patients with diabetes and hypertension. There were three arms: high‐intensity, low‐intensity, and usual care. Both intervention groups received care management from a study nurse that entailed weekday monitoring. Based on responses from patients in the intervention group, the nurse delivered follow‐up in the form of providing additional health information, increased monitoring, or contacting a physician as needed. Both intervention groups were instructed to measure BP daily and blood glucose as directed by their physician. For the high‐intensity group, the multidisciplinary study team developed a branching disease management algorithm that was programmed into study devices and focused on behavior modification and lifestyle adjustments. Patients in the low‐intensity group were asked questions daily, but were not exposed to the branching algorithm. The high‐intensity patients had a significant decrease in systolic BP compared with the other groups at 6 months and this pattern was maintained at 12 months.27

The final study using behavioral strategies without medication management is unique in two ways. First, the Posts Working for Veterans Health (POWER) study15, 16, 29 was conducted in a Veterans Service Organization (VSO). In addition, rather than relying exclusively on medical professionals to serve as interventionists it uses peer leaders. All posts received a digital bathroom scale, pedometers, and automated BP monitors. The professionally led groups held three 90‐minutes sessions, which were advertised and repeated six times around the study area (ie, southeastern Wisconsin) so that at least one meeting was convenient for all participants. Peer leaders were trained prior to leading sessions. Their sessions were held monthly at the post and included approximately 12‐minute “health corner” presentations on a specific topic such as physical activity, medication adherence, or other important topic. Peer leaders underwent eight mini‐training sessions to equip them with a script to deliver the intervention. Hypertensive peer leaders lowered their systolic BP by 3.93 mm Hg (P=.04) and engaged in healthier behaviors compared with leaders from other groups.15

Discussion

Several conclusions can be drawn. First, while many interventions reported in this study effectively improved BP control, they did so using a myriad of approaches. Peers, nurses, primary care providers, and pharmacists delivered interventions. Settings varied from home‐based with telephone support to clinic‐ or community‐based. Educational content, contact frequency, and intervention intensity were mixed. Many of the successful interventions relied on increased frequency of contact. As an integrated healthcare system, the VA is unique in that it bridges services related to diagnosis, treatment, medication management, and behavioral counseling, among others. As healthcare delivery evolves, with more organizations adopting an Accountable Care Organization model, this may become increasingly possible in traditionally nonintegrated healthcare settings. Additionally, the VA emphasizes quality monitoring and improvement. While not specifically addressed in the included studies, this culture and model of care may be at least partially responsible for creating an environment where these interventions can be carried out and successfully improve hypertension control.

Conclusions

While there is no universal solution to improve hypertension, there are several common ingredients among interventions that successfully improve medication adherence and often improve BP control.30

Funding and Author contribution

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors report no specific funding in relation to this research and no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr Zullig is supported by a Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award (CDA 13‐025). Dr Bosworth is supported by a Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Senior Career Scientist Award (HSRD 08‐027).

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:827–837. Published 2014. This article is a U.S. Government work and is in the public domain in the USA.

References

- 1. Fletcher RD, Amdur RL, Kolodner R, et al. Blood pressure control among US veterans: a large multiyear analysis of blood pressure data from the Veterans Administration health data repository. Circulation. 2012;125:2462–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bosworth HB, Dudley T, Olsen MK, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control: potential explanatory factors. Am J Med. 2006;119:70.e9–70.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Gentry P, et al. Nurse administered telephone intervention for blood pressure control: a patient‐tailored multifactorial intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Goldstein MK, et al. The veterans' study to improve the control of hypertension (V‐STITCH): design and methodology. Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:155–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Datta SK, Oddone EZ, Olsen MK, et al. Economic analysis of a tailored behavioral intervention to improve blood pressure control for primary care patients. Am Heart J. 2010;160:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heisler M, Hofer TP, Klamerus ML, et al. Study protocol: the Adherence and Intensification of Medications (AIM) study–a cluster randomized controlled effectiveness study. Trials. 2010;11:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heisler M, Hofer TP, Schmittdiel JA, et al. Improving blood pressure control through a clinical pharmacist outreach program in patients with diabetes mellitus in 2 high‐performing health systems: the adherence and intensification of medications cluster randomized, controlled pragmatic trial. Circulation. 2012;125:2863–2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roumie CL, Elasy TA, Greevy R, et al. Improving blood pressure control through provider education, provider alerts, and patient education: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roumie CL, Elasy TA, Wallston KA, et al. Clinical inertia: a common barrier to changing provider prescribing behavior. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thorpe CT, Bryson CL, Maciejewski ML, Bosworth HB. Medication acquisition and self‐reported adherence in veterans with hypertension. Med Care. 2009;47:474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thorpe CT, Oddone EZ, Bosworth HB. Patient and social environment factors associated with self blood pressure monitoring by male veterans with hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10:692–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Olsen MK, et al. Home blood pressure management and improved blood pressure control: results from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1173–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jackson GL, Oddone EZ, Olsen MK, et al. Racial differences in the effect of a telephone‐delivered hypertension disease management program. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1682–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magid DJ, Ho PM, Olson KL, et al. A multimodal blood pressure control intervention in 3 healthcare systems. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:e96–e103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mosack KE, Patterson L, Brouwer AM, et al. Evaluation of a peer‐led hypertension intervention for veterans: impact on peer leaders. Health Educ Res. 2013;28:426–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mosack KE, Wendorf AR, Brouwer AM, et al. Veterans service organization engagement in ‘POWER,' a peer‐led hypertension intervention. Chronic Illn. 2012;8:252–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang V, Smith VA, Bosworth HB, et al. Economic evaluation of telephone self‐management interventions for blood pressure control. Am Heart J. 2012;163:980–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Melnyk SD, Zullig LL, McCant F, et al. Telemedicine cardiovascular risk reduction in veterans. Am Heart J. 2013;165:501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zullig LL, Melnyk SD, Stechuchak KM, et al. The Cardiovascular Intervention Improvement Telemedicine Study (CITIES): rationale for a tailored behavioral and educational pharmacist‐administered intervention for achieving cardiovascular disease risk reduction. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:135–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cohen LB, Taveira TH, Khatana SA, et al. Pharmacist‐led shared medical appointments for multiple cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37:801–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bosley F, Allen TW. Stress management training for hypertensives: cognitive and physiological effects. J Behav Med. 1989;12:77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brauer AP, Horlick L, Nelson E, et al. Relaxation therapy for essential hypertension: a Veterans Administration Outpatient study. J Behav Med. 1979;2:21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edelman D, Fredrickson SK, Melnyk SD, et al. Medical clinics versus usual care for patients with both diabetes and hypertension: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rifkin DE, Abdelmalek JA, Miracle CM, et al. Linking clinic and home: a randomized, controlled clinical effectiveness trial of real‐time, wireless blood pressure monitoring for older patients with kidney disease and hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 2013;18:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taveira TH, Friedmann PD, Cohen LB, et al. Pharmacist‐led group medical appointment model in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vivian EM. Improving blood pressure control in a pharmacist‐managed hypertension clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:1533–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wakefield BJ, Holman JE, Ray A, et al. Effectiveness of home telehealth in comorbid diabetes and hypertension: a randomized, controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2011;17:254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hayes A, Morzinski J, Ertl K, et al. Preliminary description of the feasibility of using peer leaders to encourage hypertension self‐management. WMJ. 2010;109:85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zullig LL, Peterson ED, Bosworth HB. Ingredients of successful interventions to improve medication adherence. JAMA. 2013;310:2611–2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Whittle J, Fletcher KE, Morzinski J, et al. Ethical challenges in a randomized controlled trial of peer education among veterans service organizations. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2010;5:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]