Abstract

Hypertension is common following renal transplantation and has adverse effects on cardiovascular and graft health. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) is better at overall blood pressure (BP) assessment and is necessary to diagnose nocturnal hypertension, which is also implicated in poor outcomes. The authors performed a retrospective analysis of 98 renal transplant recipients (RTRs) and compared office BP and ambulatory BP recordings. ABPM revealed discordance between office BP and ambulatory BP in 61% of patients, with 3% caused by white‐coat and 58% caused by masked hypertension (of which 33% were caused by isolated nocturnal hypertension). Overall, mean systolic BP was 3.6 mm Hg (0.5–6.5) and diastolic BP was 7.5 mm Hg (5.7–9.3) higher via ambulatory BP than office BP. This was independent of estimated glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, transplant time/type, and comorbidities. A total of 42% of patients had their management changed after results from ABPM. ABPM should be routinely offered as part of hypertension management in RTRs.

Post–renal transplant hypertension affects the majority of transplant recipients. It is noted that up to 90% (depending on cutoffs and series) of renal transplant recipients are either reported to have hypertension or to be taking antihypertensive drugs.1, 2 We also know that hypertension not only increases the risk of poor cardiovascular outcomes, which is the leading cause of death in this demographic, but also increases the risk of graft failure.3, 4 In fact, uncontrolled hypertension can precede graft dysfunction by a number of years.3 Although it is hard to establish causality absolutely between uncontrolled hypertension and graft and patient outcomes, it is well established that lowering blood pressure (BP) improves both. In a registry of 24,404 patients, even a temporary rise in BP at 3 years was associated with poor long‐term outcomes.5

Guidelines for BP targets by different agencies vary slightly but most recommend a target of 130/80 mm Hg. The National Kidney Foundation's Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommend a target BP <130/80 mm Hg and even lower for those with significant proteinuria or presence of comorbid conditions such as established atherosclerotic disease.6, 7 The European Best Practice Guidelines recommend a BP <125/75 mm Hg in patients who are proteinuric.8 Despite this, although improving in recent years, there are data to suggest that up to 50% of recipients do not achieve systolic BP <140 mm Hg at 1 year.3, 5

Clearly, accurate BP measurement becomes all the more important. Traditionally, BP has been checked in the office, but the role of ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) has increasingly been recognized.1, 9, 10, 11, 12 In the general population, ABPM predicts future cardiovascular events significantly better than manual office BP.13 Studies comparing office and ambulatory BP in renal transplant recipients (RTRs) are increasingly reporting a discrepancy with masked hypertension (where office BP is normal and ambulatory BP higher) as well as the opposite scenario of white‐coat hypertension. Both have treatment implications.1, 14

Furthermore, there are normal diurnal BP patterns that are disrupted in RTRs. These abnormal patterns—nondipping or reverse dipping (defined as a <10% nocturnal BP fall or rise, respectively)—are important risk factors for left ventricular hypertrophy, increased renal resistivity index leading to poor cardiovascular and graft outcomes.15 This can only be assessed with ABPM and has been shown to be a better predictor of cardiovascular outcomes than office BP.16 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which provides medical guidance in the United Kingdom, recommends use of ABPM in the first diagnosis of hypertension when possible; the need in transplant recipients, one can postulate, is indeed higher.17 However, ABPM is cumbersome and not an inexpensive tool. Although increasingly recognized as valuable, it has yet to become standard of care in the renal transplant population.

In light of this, we set out to compare BP control with office and ambulatory measurements in RTRs and the rates of nocturnal hypertension and to examine how the information obtained changed management.

Study Population and Methods

The care of patients is transferred from the regional transplanting center (Auckland Hospital) routinely 2 to 3 months after transplantation. Our renal unit was established in 2011; therefore, RTRs with older grafts who were previously followed up in Auckland Hospital from our catchment area were transferred over upon inception.

All stable patients (those with stable serum creatinine and BP levels or those who did not require ongoing follow‐up and input from Auckland Hospital with regards to surgical or other issues) who had received a transplant more than 3 months prior were eligible to be participants. We routinely perform ABPM on new recipients 3 to 6 months post‐transfer. In addition, long‐term transplant patients also received a baseline ABPM study when transferred. ABPM was performed for 24 hours and the devices were fitted on either one of their outpatient visits or separately by technicians from the cardiac laboratory using the same monitor. Reports were generated on all patients in a standard manner by laboratory reading the monitor. In the minority of patients who had more than one study during the period, the index ABPM was used for analysis. Office BPs were recorded from clinic notes (an average of all available office readings within the study period). These were taken in morning clinics manually while the patient was seated. These were not standardized as they were taken by different people and it is unknown whether single or multiple readings were used.

We performed a retrospective analysis on 98 consecutive patients between 2010 and 2011. Data were collected on demographics (age, sex, body mass index), primary renal disease, time since and type of transplant, presence of hypertension, number and type of antihypertensive drugs, number and type of immunosuppressant, presence and quantity of proteinuria, and current eGFR. We then compared office BP and recorded information from ABPM—average awake, average asleep, and highest early morning BP. Targets for office BP were set at 130/80 mm Hg, and those for ABPM were also derived from this target. Thus, average day BP was <130/80 mm Hg, 24‐hour average BP <125/75 mm Hg, and target nocturnal BP (expecting a normal physiological drop of 10 mm Hg of BP overnight) was set at 120/70 mm Hg. Ambulatory hypertension was defined as any of these above targets. We subsequently examined the clinical notes to review concordance with the office BP and whether management changes had been made based on the information obtained by ABPM.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were tested for normality by the Shapiro‐Wilk test. Comparisons between normally distributed groups using paired t test were made to generate P values. A P<.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the R software package.

Results

Patient characteristics are as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Patient Population

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Female sex, % | 40 |

| Live donor transplant, % | 42 |

| Average age, y | 55.3 (range 19–84) |

| Average BMIa | 27.26 (range 18.21–39.24) |

| Transplant vintage, y | 8.5 (range 1–39) |

| eGFR (MDRD) | 52.06 (range 16–90+) |

| Use of at least 1 antihypertensive agent, % | 91 |

| Diabetes, % | 17 |

| Established atherosclerosis (IHD, CVD), % | 18 |

| Calcineurin inhibitor use, % | 91 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IHD, ischemic heart disease; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.

Data missing on 14 patients.

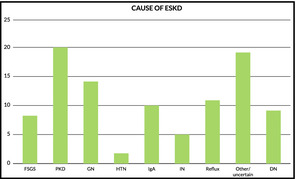

The original cause of end‐stage kidney disease is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Causes of end‐stage kidney disease. FSGS indicates focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; PKD, polycystic kidney disease; GN, glomerulonephritis; HTN, hypertension; IN, interstitial nephritis; DN, diabetic nephropathy.

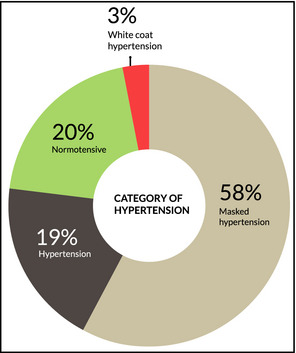

In our study, only 20.4% of patients had concordant normotension and only 18.4% had concordant hypertension. While the office BPs of 78.5% of patients overall were at target, almost three quarters of these were not according to ABPM, giving an overall masked hypertension rate of 58%. Of those with masked hypertension, 33% of these were caused by isolated nocturnal hypertension. Overall, 71% of patients did not achieve an average asleep BP of 120/70 mm Hg.

Conversely, 3% of patients had white‐coat hypertension. In other words, when compared with ambulatory BPs, office BP failed to predict true BP in 61% of patients. In our study, 42% of patients underwent changes to antihypertensive medications post‐ABPM, which comprised the majority (72%) of patients with discordant readings between both methods (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Blood pressure (BP) categories after ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM).

On the whole, we estimated with 95% confidence that mean systolic BP on ABPM was 3.6 mm Hg (0.5–6.7 mm Hg) higher than office BP. This difference was even more pronounced with diastolic BP (7.5 mm Hg [5.7–9.3 mm Hg]) (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

BP in Patients at Target (95% Confidence Intervals)a

| Mean BPs of patients at target | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office BP | Average ABPM | Awake ABPM | Night ABPM | |

| Normotension 20.4% | 117/66 (14/10) | 114/69 (13/11) | 116/71 (15/12) | 107/63 (11/9) |

| White‐coat hypertension 3% | 138/73 (23/16) | 124/75 (5/5) | 125/75 (10/4) | 116/68 (6/1) |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP, blood pressure.

Rounded off to the nearest mm Hg.

Table 3.

BP in Patients Not at Target (95% Confidence Intervals)a

| Mean BPs NOT at target | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office BP | Average ABPM | Awake ABPM | Night ABPM | |

| Hypertension 18.4% | 138/77 (14/18) | 134/81 (25/15) | 135/83 (30/15) | 130/78 (25/16) |

| Masked hypertension 58% | 122/70 (14/12) | 131/80 (23/15) | 132/81 (24/16) | 128/77 (31/21) |

| Isolated nocturnal hypertension (33% of masked) | 125/70 (9/11) | 124/75 (10/10) | 123/75 (9/10) | 124/75 (17/11) |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP, blood pressure.

Rounded off to the nearest mm Hg.

Upon checking for possible confounders, there was no evidence to suggest that the difference in BP as a result of measurement technique was correlated in any way with proteinuria, degree of chronic kidney disease, diabetes, or time from/type of transplant. However, when the systolic BP was adjusted for female sex, the difference wasn't statistically significant (P=.09). The clinical significance of this is unknown.

Discussion

Optimal office BP targets in RTRs are unknown. Treatment targets by societies have largely been based on extrapolation from the chronic kidney disease population (without transplants), and even those have been questioned by the new Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) guidelines.18 KDIGO, for example, grades its evidence for 130/80 mm Hg as 2C (weak recommendation with a low quality of evidence). A post hoc analysis on the Folic Acid for Vascular Outcome Reduction in Transplantation (FAVORIT) trial, which assessed the association of BP with pooled cardiovascular disease outcomes and all‐cause mortality in the original cohort, has shed some light on the subject and confirmed that higher levels of systolic BP are independently associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease and all‐cause mortality without having a lower threshold below which risk also rises (the same could not be said for diastolic BP).19

Optimal targets for ambulatory BPs in this population have not been well defined and there is a variance across the studies on these, largely arbitrary, cutoffs. For example, RETENAL (which also looked at ABPM in RTRs and its correlation with office BP) defined “controlled BP” as a mean 24‐hour BP of <130/85 mm Hg and Wen and colleagues as 135/85 mm Hg.9, 10 Our definitions (as those shared by Paoletti and colleagues1) were derived from an average daytime target of 130/80 mm Hg; hence, they are about 5 mm Hg lower across the board. Unlike those for the general population (where normotension and hypertension are defined by separate criteria with a 5 mm Hg window in between), our patients were either “at target,” ie, assumed normotensive, or not.

Clearly, then, how one defines normotension on ABPM and office BP affects how one categorizes a patient. Wen and colleagues defined hypertension as 140/90 mm Hg and therefore found that 45% had normal daytime ABPM (consistent with office BP) and therefore a good proportion have white‐coat hypertension.10 Similarly, RETENAL (<130/85 mm Hg) found that 65% of patients had white‐coat hypertension.9 Both show a good proportion of patients had nocturnal hypertension. Paoletti and colleagues also showed a very significant proportion (79%) were either nondippers or reverse dippers. This asleep diastolic BP was a significant predictor of creatinine level at 1 year.1

Clearly, ABPM provides that extra bit of clarity on a 24‐hour (including nocturnal) BP profile in a patient that an one‐off clinic measurement just cannot, which provides prognostic information. Our study adds to the growing body of literature on the subject and shows major discrepancies between office BP and ambulatory BP.

Our high rates of masked hypertension and relatively fewer cases of white‐coat hypertension compared with others is likely a reflection of tighter BP thresholds as well as the inclusion of nocturnal hypertension in the group. The most common pattern in patients with masked hypertension was for the awake‐average BP to be just below or just above the target of 130/80 mm Hg, but with very little drop overnight so that the asleep average was more commonly and more significantly clearly above target.

The proper method of BP requires that attention be paid to many patient, equipment, and technique factors. It is likely that one or more of these are missing.20 Our office BP measurements were not standardized in any way. However, others have still shown nonconcordance despite standardization.1, 10

Home BP monitoring has been shown to be more accurate than manual office BP; however, it is still not as good as ABPM when it is used as the standard.21 There have also been calls for manual office BP to be replaced by automated office BP measurements.22 This has been reported to largely diminish the white‐coat effect and has better correlation with ABPM.23 However, both automated office BP and home BP monitoring still fail to capture the significant proportion of patients with nocturnal hypertension.

In an open‐label trial, it was demonstrated that patients with chronic kidney disease who took at least one antihypertensive at bedtime had a significantly reduced risk for total cardiovascular events as well as a composite end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke, compared with those taking all agents in the morning. They had a significantly lower nocturnal BP, and a greater proportion had overall better ambulatory control. Each 5‐mm Hg drop in nocturnal systolic BP was associated with a 14% reduction in risk of cardiovascular events at follow‐up.24 Although we collected data on the number of antihypertensive agents patients were taking, we did not assess how many were administered at night, as this information at the time of data collection was not thought imperative. In light of the above study, along with information obtained from ABPM, one would endeavor to prescribe at least some antihypertensive agents at night.

Conclusions

We made changes to management after ABPM in a significant, much larger‐than‐anticipated, group of patients based on current guidelines. At this stage, we would use ABPM to guide our therapy to prevalent BP “targets.” Whether this will change outcome in the long‐term is difficult assess as there are no longitudinal studies that investigate outcomes in patients whose BPs are guided by ABPM. This study was not designed to investigate these outcomes, as it was a relatively small observational study. Given the relative infrequency of testing in our initial cohort, we need only one device for all measurements. At this preliminary stage, a proper cost‐benefit analysis cannot be undertaken. We do not anticipate that it will significantly add to transplant unit costs. All things taken into account, with the limitations of our study, we believe ABPM should be considered as part of routine management of hypertension in RTRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Anzar Chida, BA (Statistics), for help with statistical analysis.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015;17:46–50. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12448. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Paoletti E, Gherzi M, Amidone M, et al. Association of arterial hypertension with renal target organ damage in kidney transplant recipients: the predictive role of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Transplantation. 2009;87:1864–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wadei HM, Textor SC. Hypertension in the kidney transplant recipient. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2010;24:105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kasiske BL, Anjum S, Shah R, et al. Hypertension after kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Opelz G, Wujciak T, Ritz E. Association of chronic kidney graft failure with recipient blood pressure. Collaborative Transplant Study. Kidney Int. 1998;53:217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Opelz G, Dohler B. Improved long‐term outcomes after renal transplantation associated with blood pressure control. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2725–2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. K/DOQI . K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5 Suppl 1):S1–S290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. KDIGO . KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9 Suppl 3:S1–S155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. European best practice guidelines for renal transplantation . Section IV: long‐term management of the transplant recipient. IV.5.2. Cardiovascular risks. Arterial hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(Suppl 4):25–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernandez Fresnedo G, Franco Esteve A, Gomez Huertas E, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in kidney transplant patients: RETENAL study. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2601–2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wen KC, Gourishankar S. Evaluating the utility of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:E465–E470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Covic A, Segall L, Goldsmith DJ. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in renal transplantation: should ABPM be routinely performed in renal transplant patients? Transplantation. 2003;76:1640–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stenehjem AE, Gudmundsdottir H, Os I. Office blood pressure measurements overestimate blood pressure control in renal transplant patients. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hansen TW, Jeppesen J, Rasmussen S, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure and mortality: a population‐based study. Hypertension. 2005;45:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haydar AA, Covic A, Jayawardene S, et al. Insights from ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: diagnosis of hypertension and diurnal blood pressure in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2004;77:849–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wadei HM, Amer H, Taler SJ, et al. Diurnal blood pressure changes one year after kidney transplantation: relationship to allograft function, histology, and resistive index. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1607–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bobrie G, Clerson P, Menard J, et al. Masked hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1715–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mayor S. Hypertension diagnosis should be based on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, NICE recommends. BMJ. 2011;343:d5421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carpenter MA, John A, Weir MR, et al. BP, cardiovascular disease, and death in the folic acid for vascular outcome reduction in transplantation trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1554–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spranger CB, Ries AJ, Berge CA, et al. Identifying gaps between guidelines and clinical practice in the evaluation and treatment of patients with hypertension. Am J Med. 2004;117:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hodgkinson J, Mant J, Martin U, et al. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Myers MG. Why automated office blood pressure should now replace the mercury sphygmomanometer. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:478–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Optimum frequency of office blood pressure measurement using an automated sphygmomanometer. Blood Press Monit 2008;13:333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojon A, Fernandez JR. Bedtime dosing of antihypertensive medications reduces cardiovascular risk in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2313–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]