Abstract

High parathyroid hormone (PTH) has been linked with high blood pressure (BP), but the relationship with 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is largely unknown. The authors therefore analyzed cross‐sectional data of 292 hypertensive patients participating in the Styrian Hypertension Study (mean age, 61±11 years; 53% women). Median plasma PTH (interquartile range) determined after an overnight fast was 49 pg/mL (39–61), mean daytime BP was 131/80±12/9 mm Hg, and mean nocturnal BP was 115/67±14/9 mm Hg. In multivariate regression analyses adjusted for BP and PTH‐modifying parameters, PTH was significantly related to nocturnal systolic and diastolic BP (adjusted β‐coefficient 0.140 [P=.03] and 0.175 [P<.01], respectively). PTH was not correlated with daytime BP readings. These data suggest a direct interrelationship between PTH and nocturnal BP regulation. Whether lowering high PTH concentrations reduces the burden of high nocturnal BP remains to be shown in future studies.

Arterial hypertension (HTN) is a pandemic disease accounting for high morbidity and mortality.1 High parathyroid hormone (PTH) has been linked with HTN,2, 3 and some studies have pointed towards impaired “dipping” of blood pressure (BP) during the night in patients with high PTH.4, 5 However, the relationship between PTH and parameters of 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) in hypertensive patients is largely unknown.

PTH is produced in the parathyroid glands and is secreted in an endogenous circadian rhythm, reaching peak levels during the night between 2 am and 4 am.6 By directly or indirectly promoting calcium absorption from the intestines, bone, and the kidney, PTH is crucial for maintaining circulating calcium levels within physiological ranges. This becomes particularly important in conditions of calcium deficiency such as vitamin D deficiency, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure.7

Previous studies have documented that high PTH is associated with activation of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system, left ventricular hypertrophy, incident heart failure, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, atherosclerosis, and increased cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The relationship between PTH and HTN as a crucial predisposing pathophysiological condition for cardiovascular disease has been indicated in previous studies. Infusion of physiological doses of PTH raises BP in humans.13 Elevated PTH predicts new incident HTN independently of important potential confounders.14, 15, 16 In addition, in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, a condition of autonomous excess secretion of PTH, the prevalence of HTN is markedly increased.3 Hypertensive patients with primary hyperparathyroidism have been shown to have a higher prevalence of nondipping pattern when compared with hypertensive patients without primary hyperparathyroidism,4 and parathyroidectomy has been related to reduced mean systolic daytime BP in another cohort of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism.17 However, only one previous analysis studied the relationship between PTH and parameters of 24‐hour ABPM in hypertensive patients and found that higher PTH was associated with higher prevalence of a nondipping pattern.5

Therefore, we aimed to assess the relationship between PTH and daytime as well as nighttime BP adjusting for potential confounders in a cohort of hypertensive patients. In addition, we tried to further elucidate the role of plasma aldosterone (PAC) and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) as potential effect modifiers.

Methods

Patients and Setting

The current investigation utilized cross‐sectional data from the Styrian Hypertension Study, a cohort study in hypertensive patients derived from outpatient clinics of the Medical University of Graz, Austria.18, 19 The aim of this study was to investigate biomarkers in relation to HTN and cardiovascular risk factors in hypertensive patients. Briefly, inclusion criteria were age 8 years and older and a history of HTN as defined according to medical records or patient interview. Main exclusion criteria were stroke or myocardial infarction in the past 4 weeks, pregnancy and lactating in women, and estimated life expectancy of less than a year. Life expectancy was empirically judged by an experienced clinician who took into account the patient's medical history, present comorbidities, and medications used. Further details with regards to the study design and setting have been previously reported.18, 19 All patients provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and complied with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

For the present analysis we included all patients who participated in the study screening between June 2011 and September 2013 and who had available PTH measurements and valid ABPM.

Laboratory and ABPM Assessment

Blood samplings were performed during the morning (7 am – 11 am) after 12 hours of fasting. Before blood sampling, patients remained in the seated position for at least 10 minutes. All blood‐derived parameters were determined at least 4 hours after collection. Before analyses, all samples were kept at room temperature, except for those used to determine PAC and PTH, which were kept at 4°C. PTH (in pg/mL) was measured from plasma with a sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on an Elecsys 2010 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Intra‐assay and interassay coefficients of variation (CV) were 1.5% (at 261 pg/mL) to 2.7% (at 26.7 pg/mL) and 3.0% (at 261 pg/mL) to 6.5% (26.7 pg/mL), respectively, with a reference range of 15 pg/mL to 65 pg/mL. This second‐generation PTH assay measures intact PTH (1–84) by using two antibodies against the C‐terminal (1–37) and the N‐terminal fragment (38–84) of PTH, in opposition to third‐generation assays detecting PTH (1–4). Both second‐ and third‐generation assays show cross‐reactions with other PTH fragments and are considered equivalently useful in international guidelines.20 NT‐proBNP (in pg/mL) was measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay based on a polyclonal antibody‐based sandwich chemiluminescence assay (Roche Diagnostics) using an autoanalyzer (Elecsys 2010). PAC (in ng/dL) was determined by means of an RIA (Active Aldosterone RIA DSL‐8600; Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc, Webster, TX) with an intra‐assay and interassay CV of 3.3% to 4.5% and 5.9% to 9.8%, respectively. Plasma 25‐hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) (in ng/mL) was determined using a chemiluminescence assay (IDS‐iSYS 25‐hydroxyvitamin D assay; Immunodiagnostic Systems Ltd, Boldon, United Kingdom) on an IDS‐iSYS multidiscipline automated analyzer. Within‐day CV were 5.5% to 12.1%, and inter‐day CV were 8.9% to 16.9%. All other parameters were determined by routine laboratory procedures. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated based on serum creatinine in mL/min/m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation 2012.

A continuous 24‐hour ABPM portable device (Spacelabs 90217A, firmware version 03.02.16; Spacelabs Healthcare, Inc, Issaquah, WA) was used to perform the 24‐hour ABPM. The circumference of the upper arm was measured in all patients to select the appropriate cuff for BP recordings. All measurements were recorded and analyzed by trained personnel at the Medical University of Graz, Austria. BP was recorded every 15 minutes during the day and every 30 minutes during the night.

Definitions

Primary hyperparathyroidism was defined as a constellation of hypercalcemia (total serum albumin adjusted calcium >2.55 mmol/L) in concomitance with an inappropriately high PTH level of >46 pg/mL at the study baseline visit.20 Nocturnal BP and daytime BP were defined according to international guidelines as the means of measurements obtained between 1 am and 6 am and between 9 am and 9 pm, respectively.21 Mean BP was defined as the means of all measurements obtained within 24 hours. Nocturnal HTN was defined as a mean nocturnal systolic BP (SBP) ≥120 mm Hg or a mean nocturnal diastolic BP (DBP) ≥70 mm Hg. Daytime HTN was defined as a mean daytime SBP ≥135 mm Hg or a mean daytime DBP ≥85 mm Hg.22 Proteinuria was defined as spot urinary protein excretion ≥200 mg/g creatinine. Data on previous myocardial infarction and stroke were collected from the patient interview.

Valid ABPM was defined as percentage of valid readings ≥70%, number of valid daytime readings ≥20, and number of valid nighttime readings ≥7 as recommended in international guidelines.21

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables are presented as either mean±standard deviation in case of a normal distribution or as median and interquartile range. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages. The distribution of numerical variables and their residuals was evaluated by skewness, kurtosis, and concordance between the mean and median, test of Kolmogorov‐Smirnov, and visual inspection. Non‐normally distributed variables were 10‐logarithmically (log) transformed before use in parametrical statistical procedures. Associations between participant characteristics were assessed using Pearson correlation or chi‐square test as appropriate. Moreover, we stratified PTH levels according to tertiles to present baseline characteristics of the cohort. In case of a significant bivariate correlation, we performed multivariate linear regression analyses with PTH for the respective ABPM reading adjusting for BP‐ and PTH‐modifying parameters. In model 1, we adjusted for age and sex as covariates. In model 2, serum low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, serum glycated hemoglobin, smoking status, and body mass index were added. Model 3 additionally comprised regular use of BP‐modifying drugs (eg, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor blocker, β‐blocker, calcium antagonist, mineralocorticoid receptor blocker, and thiazide or loop diuretic). In model 4, we additionally integrated eGFR, 25(OH)D, serum calcium, and serum phosphate. As final models, we added PAC or NT‐proBNP to the covariates of model 4, respectively. Adjusted β‐coefficients with P values are given to illustrate effect size and significance. We assessed the validity of the regression models by testing the distribution of the model residuals for normality using Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test. The relationship between PTH and respective ABPM parameters was illustrated using a cubic spline function. We additionally set up a crude and a multivariate logistic regression model with hyperparathyroidism (yes/no) for the presence of nocturnal HTN using the same covariates as in the multivariate linear regression models, with odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) as the estimates of risk and significance.

As a sensitivity check, we omitted patients with plasma PTH >65 pg/mL, with eGFR <60 mL/min/m2, or those who presented with primary hyperparathyroidism and repeated the regression analyses (model 3). In view of the interplay between PTH and aldosterone, we additionally subgrouped the cohort with regard to PAC above and below the median.8 Growing interest has been drawn to secondary hyperparathyroidism because of left ventricular failure. Therefore, we also split the cohort according to the median of NT‐proBNP.

SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses A two‐sided P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

ABPM readings as well as plasma PTH values were available in 292 patients. The mean age was 61±11 years, 53% were females (n=155), and median plasma PTH was 49 (39–61) pg/mL, with 19% of patients (n=56) presenting with a plasma PTH level above the reference range of 65 pg/mL. Mean daytime SBP was 131/80±12/9 mm Hg and mean nocturnal BP was 115/67±14/9 mm Hg. The prevalence of daytime and nocturnal HTN was 43% (n=127) and 45% (n=132), respectively. Median NT‐proBNP was 85 (46–164) pg/mL, mean eGFR was 80±19 mL/min/m2, and median 25(OH)D was 28 (21–36) ng/mL. Further baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 and across PTH tertiles in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Cohort

| Total Patients | 292 |

|---|---|

| PTH, pg/mL (normal range 15–65) | 49 (39–61) |

| Age, y | 61±11 |

| Hyperparathyroidism, No. (%) | 56 (19) |

| Primary hyperparathyroidism, No. (%) | 7 (2) |

| Females, No. (%) | 155 (53) |

| Smokers, No. (%) | 39 (13) |

| Diabetes mellitus, No. (%) | 59 (20) |

| Previous myocardial infarction, No. (%) | 21 (7) |

| Previous stroke, No. (%) | 18 (6) |

| Mean 24‐hour SBP, mm Hg | 128±12 |

| Mean 24‐hour DBP, mm Hg | 77±8 |

| Mean daytime SBP, mm Hg | 131±12 |

| Mean daytime DBP, mm Hg | 80±9 |

| Mean nocturnal SBP, mm Hg | 115±14 |

| Mean nocturnal DBP, mm Hg | 67±9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29 (26–32) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 117 (90–141) |

| Glycated hemoglobin, % | 5.7 (5.4–6.1) |

| eGFR, mL/min/m2 | 80±19 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/m2, No. (%) | 41 (14) |

| eGFR <30 mL/min/m2, No. (%) | 3 (1) |

| Proteinuria, No. (%) | 22 (7) |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 28 (21–36) |

| Albumin adjusted calcium, mmol/L | 2.39 (2.33–2.47) |

| Phosphate, mg/dL | 2.98±0.5 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 85 (46–164) |

| Aldosterone, ng/dL | 16 (11–20) |

| Regular medication use, No. (%) | |

| β‐Blocker | 156 (53) |

| ACE inhibitor | 111 (38) |

| ARB | 81 (28) |

| Calcium antagonist | 75 (26) |

| MR blocker | 10 (3) |

| Loop diuretic | 11 (4) |

| Thiazide diuretic | 120 (41) |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate, calculated according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; PTH, parathyroid hormone; SBP, systolic blood pressure; 25(OH)D, 25‐hydroxy vitamin D3. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ±standard deviation in case of normal distribution and otherwise as median (interquartile range) and categorical variables as number (percentage).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics Across Tertiles of Plasma PTH

| N=292 | First Tertile | Second Tertile | Third Tertile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | 96 | 99 | 97 |

| PTH, pg/mL (normal range 15–65) | 35 (30–39)a | 49 (46–53)a | 69 (61–82)a |

| Age, y | 59±13 | 61±10 | 61±11 |

| Women, No. (%) | 49 (51) | 52 (53) | 53 (55) |

| Smokers, No. (%) | 18 (19) | 10 (10) | 11 (11) |

| Type II diabetes, No. (%) | 25 (26) | 14 (14) | 20 (21) |

| Mean SBP, mm Hg | 128±11a | 126±12a | 130±12a |

| Mean DBP, mm Hg | 77±8 | 76±8 | 78±9 |

| Mean daytime SBP, mm Hg | 131±12 | 130±12 | 133±13 |

| Mean daytime DBP, mm Hg | 79±9 | 79±9 | 80±10 |

| Mean nocturnal SBP, mm Hg | 114±13a | 113±14a | 119±15a |

| Mean nocturnal DBP, mm Hg | 67±8 | 66±9 | 69±9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28±4a | 29±5a | 30±5a |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 118±44 | 119±35 | 112±35 |

| Glycated hemoglobin, % | 5.7 (5.4–6.3) | 5.7 (5.4–6) | 5.7 (5.5–6.1) |

| eGFR, mL/min/m2 | 84±18a | 80±16a | 76±21a |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/m2, No. (%) | 10 (10)a | 11 (10)a | 20 (21)a |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 32 (22–38)a | 28 (24–35)a | 24 (19–32)a |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.43±0.09a | 2.39±0.08a | 2.37±0.12a |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 1 (0.9–1.1)a | 0.95 (0.86–1.08)a | 0.93 (0.8–1.06)a |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 67 (44–135) | 87 (47–165) | 98 (46–226) |

| Aldosterone, ng/dL | 15 (11–20) | 15 (10–21) | 16 (12–22) |

| Primary hyperparathyroidism, No. (%) | 0a | 2 (2)a | 5 (5)a |

| Regular medication use, No. (%) | |||

| β‐Blocker | 48 (50) | 56 (57) | 52 (54) |

| ACE inhibitor | 39 (41) | 41 (41) | 31 (32) |

| ARB | 24 (25) | 24 (24) | 33 (34) |

| Calcium antagonist | 24 (25) | 23 (23) | 28 (29) |

| MR blocker | 0a | 4 (4)a | 6 (6)a |

| Loop diuretic | 1 (1)a | 2 (2)a | 8 (8)a |

| Thiazide diuretic | 37 (38) | 39 (39) | 44 (45) |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate, calculated according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; PTH, parathyroid hormone; SBP, systolic blood pressure; 25(OH)D, 25‐hydroxy vitamin D3. Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range) and categorical variables as number (percentage). a P<.05; P for trend using Kruskal‐Wallis test or analysis of variance or chi‐square test as appropriate.

After 10‐log transformation, PTH fulfilled the criteria of a normal distribution. PTH was related to mean nocturnal SBP (r=0.164, P<.01) and nocturnal DBP (r=0.148, P=.01), and was higher in patients with nocturnal HTN (HTN vs no HTN: median PTH 52 [39–65] vs 49 [39–55] pg/mL, P=.04). There was no significant correlation between PTH and daytime SBP or DBP (r=0.066 [P=.26] and r=0.038 [P=.52], respectively). Nocturnal SBP and DBP values were higher in patients taking angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, but were not associated with any other antihypertensive medication. Other correlations are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations of PTH and Nocturnal Blood Pressure Parameters With Continuous Baseline Characteristics

| PTH | Mean Nocturnal SBP | Mean Nocturnal DBP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P Value | r | P Value | r | P Value | |

| PTH | 0.155 | <.01 | 0.144 | .01 | ||

| Age, y | 0.117 | <.05 | 0.024 | .68 | −0.288 | <.01 |

| Mean SBP, mm Hg | 0.089 | .13 | 0.757 | <.01 | 0.446 | <.01 |

| Mean DBP, mm Hg | 0.074 | .21 | 0.292 | <.01 | 0.735 | <.01 |

| Mean daytime SBP, mm Hg | 0.066 | .26 | 0.573 | <.01 | 0.350 | <.01 |

| Mean daytime DBP, mm Hg | 0.038 | .52 | 0.173 | <.01 | 0.626 | <.01 |

| Mean nocturnal SBP, mm Hg | 0.164 | <.01 | 0.638 | <.01 | ||

| Mean nocturnal DBP, mm Hg | 0.148 | .01 | 0.638 | <.01 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.168 | <.01 | 0.136 | .02 | 0.001 | .98 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | −0.041 | .49 | −0.091 | .13 | 0.072 | .23 |

| Glycated hemoglobin, % | 0.004 | .95 | 0.269 | <.01 | 0.00 | 1 |

| GFR, mL/min/m2 | −0.221 | <.01 | −0.036 | .54 | 0.126 | .03 |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | −0.212 | <.01 | −0.142 | .01 | −0.048 | .42 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | −0.246 | <.01 | −0.079 | .18 | −0.117 | <.5 |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | −0.059 | .32 | −0.20 | .73 | −0.190 | <.01 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 0.196 | <.01 | 0.206 | <.01 | −0.31 | .59 |

| Aldosterone, ng/dL | 0.182 | <.01 | −0.028 | .64 | 0.064 | .28 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate, calculated according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide; PTH, parathyroid hormone; SBP, systolic blood pressure; 25(OH)D, 25‐hydroxy vitamin D3. Significant correlations are highlighted in bold.

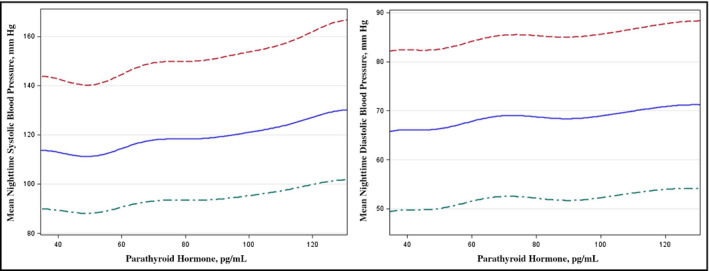

Data for the regression analyses were available in 273 patients (93.5%). Across all four multivariate regression models, shown in Table 4 and the Figure, PTH remained significantly associated with nocturnal SBP (model 4: β=0.140, P=.03) and with nocturnal DBP (model 4: β=0.175, P<.01). The residuals of both of the regression analyses were normally distributed (Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test: P>.05 for both). Additional adjustment for PAC or NT‐proBNP did not materially alter the results (data not shown). PTH >65 pg/mL (hyperparathyroidism) when compared with PTH ≤65 pg/mL was associated with an increased risk of nocturnal HTN (OR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.36–4.5). This relationship remained significant across all multivariate logistic regression models (model 4: OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.16–5.37) as presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Relationship Between Plasma Parathyroid Hormone and Nocturnal Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure in 273 Hypertensive Patients in a Multivariate Linear Regression Model

| Nocturnal Systolic Blood Pressure | Nocturnal Diastolic Blood Pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted β‐Coefficient | P Value | Adjusted β‐Coefficient | P Value | |

| Model 1 | 0.171 | <.01 | 0.189 | <.01 |

| Model 2 | 0.167 | <.01 | 0.203 | <.01 |

| Model 3 | 0.164 | <.01 | 0.212 | <.01 |

| Model 4 | 0.140 | .03 | 0.175 | <.01 |

Model 1 includes parathyroid hormone, age, and sex; model 2 adds low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycated hemoglobin, smoking status, and body mass index; model 3 adds prescription of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, β‐blocker, calcium antagonist, thiazide diuretic, and loop diuretic; and model 4 adds plasma 25‐hydroxy vitamin D, glomerular filtration rate, serum calcium, and serum phosphate.

Figure 1.

Relationship between plasma parathyroid hormone and mean nocturnal systolic blood pressure in a multivariate model (A). Relationship between plasma parathyroid hormone and mean nocturnal diastolic blood pressure in a multivariate model (B).

Table 5.

Association Between Hyperparathyroidism and Nocturnal Hypertension in 273 Hypertensive Patients in a Multivariate Logistic Regression Model

| Nocturnal Hypertension | ||

|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | |

| Model 1 | 2.68 (1.39–5.16) | <.01 |

| Model 2 | 2.73 (1.37–5.45) | <.01 |

| Model 3 | 2.93 (1.39–6.15) | <.01 |

| Model 4 | 2.5 (1.16–5.37) | .02 |

Model 1 includes parathyroid hormone, age, and sex; model 2 adds low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycated hemoglobin, diabetes mellitus, smoking status, and body mass index; model 3 adds prescription of an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, β‐blocker, calcium antagonist, thiazide diuretic, and loop diuretic; and model 4 adds plasma 25‐hydroxy vitamin D, glomerular filtration rate, serum calcium, and serum phosphate.

The relationship between PTH and both nocturnal SBP and DBP was attenuated and nonsignificant after excluding patients with a PTH >65 pg/mL (nocturnal SBP: β=−0.008, P=.907; nocturnal DBP: β=0.105, P=.120). Exclusion of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism (n=7, data not shown) or with eGFR <60 mL/min/m2 did not materially alter the results (Table 6).

Table 6.

Subgroup Analyses of the Multivariate Linear Regression Analysis (Model 3) With PTH for Nocturnal Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure in 273 Hypertensive Patients

| Selection Criterion | Median PTH, pg/mL | Systolic Nocturnal Blood Pressure | Diastolic Nocturnal Blood Pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted β‐Coefficient | P Value | Adjusted β‐Coefficient | P Value | |||

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | >85 | 49 (38–58) | 0.179 | .03 | 0.313 | <.01 |

| <85 | 51 (40–51) | 0.078 | .4 | 0.002 | .99 | |

| PAC, ng/dL | >15.5 | 52 (41–62)a | 0.149 | .10 | 0.198 | .03 |

| <15.5 | 49 (37–61)a | 0.178 | .06 | 0.166 | .08 | |

| eGFR, mL/min/m2 | ≥60 (n=234) | 49 (39–59) | 0.154 | .02 | 0.151 | .02 |

The multivariate linear regression analysis (model 3) was repeated in subgroups. Stratified analyses were based on median N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) and plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC). Mann‐Whitney U test was used to calculate differences of parathyroid hormone (PTH) between subgroups. a P<.5.

The relationship between PTH and nocturnal BP was present only in patients with higher NT‐proBNP, but was not markedly different between those with higher or lower PAC (Table 6).

Discussion

This study among hypertensive patients shows that PTH as determined after an overnight fast is not related to daytime BP, but is related to nocturnal SBP and DBP. These observations remained stable even after adjustment for classical BP‐ and PTH‐modifying parameters, suggesting a direct relationship. Moreover, hyperparathyroidism was independently related to nocturnal HTN but not to daytime HTN. This is particularly interesting because PTH secretion endogenously follows a circadian pattern that is independent of serum calcium or calcium intake.6 Our study thereby adds novel evidence to the previously defined association of PTH with high BP. Keeping in mind the increased cardiovascular risk that comes along with high nocturnal BP, these data strengthen the role of PTH as a complementary biomarker to define hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk.23 Our findings were driven by patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism (PTH >65 pg/mL) and were also present in patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/m2. While PTH secretion from the parathyroid glands is acutely stimulated by low calcium, chronic secretion is tuned by the steroid hormone 25(OH)D via activation of gene transcription.7 Chronic disease states associated with fluid retention and consecutive hypocalcemia, such as chronic kidney disease or chronic heart failure, are commonly associated with hyperparathyroidism.7, 24 This is reflected in our study as PTH was inversely correlated with serum calcium, serum 25(OH)D, and eGFR and directly with NT‐proBNP. Particularly, 25(OH)D deficiency has been previously linked to HTN. However, in most studies, vitamin D supplementation in hypertensive patients has no significant effect on BP and only modest effects on PTH.25, 26

Our finding is supported by previous clinical studies that clearly define the association of high PTH with HTN. Fliser and colleagues13 demonstrated that PTH, when administered in physiological doses as PTH 1–34, raises BP in comparison to sham infusions in healthy humans (n=10). In another study by Hulter and colleagues,27 chronic infusion of PTH 1–34 in humans (n=4) over 12 days resulted in persistent HTN that was reversed 4 to 8 days after the last infusion. In addition, in the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA),28 PTH was independently associated with impaired endothelial function and increased aortic pulse pressure. Moreover, among MESA participants not taking antihypertensive medication, hypertensive patients had higher PTH levels when compared with normotensive patients, suggesting that the link between PTH and hypertension is independent of drug intake.29 Few studies focus on ABPM parameters: Morfis and colleagues30 reported on a strong relationship between PTH and nocturnal DBP, nocturnal SBP, daytime SBP, and mean SBP in 123 elderly healthy patients with a prevalence rate of HTN of 45%. This relationship remained significant even after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, serum creatinine level, and alcohol consumption. Our study confirms this finding in a larger cohort by adding novel data with use of multivariate models with consideration of a variety of potential confounders/mediators of the PTH BP link. In addition, in a study by Kanbay and colleagues,5 high PTH was related to nondipping status in hypertensive patients in a multivariate model. In hypertensive patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, nondipping pattern was reported to be more common than in matched hypertensive patients.4 Moreover, mean daytime SBP was significantly reduced 1 year after parathyroidectomy, suggesting that surgical lowering of PTH may exert BP‐lowering effects,17 although conflicting results are also available in the literature.31 Van Ballegooijen and colleagues14 recently investigated elevated PTH as a predictor of new incident HTN in patients free from cardiovascular disease and HTN at baseline. Using data from MESA (n=3002, median follow‐up of 9 years), the researchers found that PTH >65 pg/mL was associated with an increased adjusted risk (hazard ratio, 1.27 [1.01–1.59]) for developing HTN as compared with those in the lowest PTH category. This study by Ballegooijen and colleagues confirms previous longitudinal analyses.15, 16, 17

Accumulating evidence points toward joint pathways between PTH and aldosterone and joint effects on cardiovascular mortality.32, 33 Vaidya and colleagues34 demonstrated that aldosterone antagonism with spironolactone reduced circulating PTH in participants without primary hyperparathyroidism further strengthening the conception of a clinically relevant interaction between aldosterone and PTH. In another analysis of MESA data, they also showed that aldosterone antagonism was associated with lower PTH levels.29 However, in our study, the relationship between PTH and nocturnal BP was only marginally modified by PAC, raising doubt on the relevance of the PTH aldosterone axis for the regulation of nocturnal BP in hypertensive patients.

Increased fluid retention in the setting of left ventricular failure, for instance, may have confounded our observation. In the present study, PTH correlated with NT‐proBNP as a marker of fluid overload. Indeed, this correlation has been well defined by others.35 To this end, it is commonly assumed that states of fluid retention such as chronic heart failure lead to elevated PTH levels via aldosterone‐driven renal calcium elimination.36 Notably, the relationship between PTH and nocturnal BP was present only in patients with NT‐proBNP above the median, although PTH levels did not differ between patients with NT‐proBNP above and below the median. Adding NT‐proBNP to the regression model left our results materially unchanged.

Study Strengths

Our study bears some strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study to analyze the relationship between PTH and nocturnal BP in hypertensive patients. One major strength of this study is its clinical relevance. By showing an increase of the risk of nocturnal HTN above the PTH cutoff of 65 pg/mL, our study might have a direct impact on clinical decision‐making. Further strengths include the comprehensive and highly standardized assessment of anthropometric data and biomarkers after an overnight fast. Moreover, we carefully selected patient data by applying the validity criteria of ABPM as advocated by the European Society of Hypertension.21

Study Limitations

Our study is limited by its cross‐sectional nature. Therefore, no firm conclusions can be drawn with respect to a causal relationship. Although we comprehensively adjusted for ongoing antihypertensive medication, we cannot totally exclude that intake of antihypertensive drugs in the evening may have confounded our observations. Moreover, our study lacks more profound data on left ventricular structure and function so that we had to rely on NT‐proBNP. Other drawbacks are lack of a normotensive control group and selection bias as recruitment was performed at a tertiary care hospital. Therefore, our results are not likely to be extrapolated to other populations.

Conclusions

Among hypertensive patients, PTH was independently associated with nocturnal SBP and DBP and hyperparathyroidism was linked with nocturnal HTN. These data suggest a direct interrelationship between high PTH and high nocturnal BP. It remains to be shown in future studies whether the reduction of circulating PTH concentrations reduces the burden of nocturnal HTN.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Nicolas Verheyen is funded by the Austrian National Bank (Jubilaeumsfond: project number 14621) and by the Austrian Society for Bone and Mineral Research (Felix‐Bronner Grant 2014). Katharina Kienreich and Martin Gaksch received funding support from the Austrian National Bank (Jubilaeumsfond: project number 13878 and 13905). Andreas Tomaschitz is partially supported by the project EU‐MASCARA (“Markers for Sub‐Clinical Cardiovascular Risk Assessment”; [HEALTH.2011.2.4.2‐2]; grant agreement number 278249) and by the project EU‐HOMAGE (“Validation of ‐omics‐based biomarkers for diseases affecting the elderly” [HEALTH.2012.2.1.1‐2]; grant agreement number 305507) and EU‐SYSVASC ([HEALTH.2013.2.4.2‐1]; “Systems Biology To Identify Molecular Targets For Vascular Disease Treatment”; grant agreement number 603288).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Laboratory of the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism for its work and support for the present research.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18 543–550. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12710. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Contributed equally to this work as first and corresponding author.

References

- 1. Sytkowski PA, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Secular trends in long‐term sustained hypertension, long‐term treatment, and cardiovascular mortality. The Framingham Heart Study 1950 to 1990. Circulation. 1996;93:697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCarron DA, Pingree PA, Rubin RJ, et al. Enhanced parathyroid function in essential hypertension: a homeostatic response to a urinary calcium leak. Hypertension. 1980;2:162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lafferty FW. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Changing clinical spectrum, prevalence of hypertension, and discriminant analysis of laboratory tests. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Letizia C, Ferrari P, Cotesta D, et al. Ambulatory monitoring of blood pressure (AMBP) in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kanbay M, Isik B, Akcay A, et al. Relation between serum calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone and ‘nondipper’ circadian blood pressure variability profile in patients with normal renal function. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jubiz W, Canterbury JM, Reiss E, Tyler FH. Circadian rhythm in serum parathyroid hormone concentration in human subjects: correlation with serum calcium, phosphate, albumin, and growth hormone levels. J Clin Invest. 1972;51:2040–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fraser WD. Hyperparathyroidism. Lancet. 2009;374:145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tomaschitz A, Ritz E, Pieske B, et al. Aldosterone and parathyroid hormone interactions as mediators of metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Metab, Clin Exp. 2014;63:20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Ballegooijen AJ, Visser M, Cotch MF, et al. Serum vitamin D and parathyroid hormone in relation to cardiac structure and function: the ICELAND‐MI substudy of AGES‐Reykjavik. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2544–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hagström E, Ingelsson E, Sundström J, et al. Plasma parathyroid hormone and risk of congestive heart failure in the community. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:1186–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hagström E, Michaëlsson K, Melhus H, et al. Plasma‐parathyroid hormone is associated with subclinical and clinical atherosclerotic disease in 2 community‐Based Cohorts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1567–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Ballegooijen AJ, Reinders I, Visser M, Brouwer IA. Parathyroid hormone and cardiovascular disease events: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of prospective studies. Am Heart J. 2013;165:655–664, 664.e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fliser D, Franek E, Fode P, et al. Subacute infusion of physiological doses of parathyroid hormone raises blood pressure in humans. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:933–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Ballegooijen AJ, Kestenbaum B, Sachs MC, et al. Association of 25‐hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone with incident hypertension: MESA (Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1214–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taylor EN, Curhan GC, Forman JP. Parathyroid hormone and the risk of incident hypertension. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1390–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jorde R, Svartberg J, Sundsfjord J. Serum parathyroid hormone as a predictor of increase in systolic blood pressure in men. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1639–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Norenstedt S, Pernow Y, Brismar K, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism and metabolic risk factors, impact of parathyroidectomy and vitamin D supplementation, and results of a randomized double‐blind study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169:795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grübler MR, Kienreich K, Gaksch M, et al. Aldosterone to active renin ratio is associated with nocturnal blood pressure in obese and treated hypertensive patients: the styrian hypertension study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O HB, Gaksch M, Kienreich K, et al. Associations of daytime, nighttime, and 24‐hour heart rate with four distinct markers of inflammation in hypertensive patients: the styrian hypertension study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014;16:856–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eastell R, Brandi ML, Costa AG, et al. Diagnosis of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: proceedings of the fourth international workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3570–3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, et al. European Society of Hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1731–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dolan E, Stanton A, Thijs L, et al. Superiority of ambulatory over clinic blood pressure measurement in predicting mortality: the Dublin outcome study. Hypertension. 2005;46:156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Altay H, Zorlu A, Binici S, et al. Relation of serum parathyroid hormone level to severity of heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Witham MD, Ireland S, Houston JG, et al. Vitamin D therapy to reduce blood pressure and left ventricular hypertrophy in resistant hypertension: randomized, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2014;63:706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Witham MD, Price RJG, Struthers AD, et al. Cholecalciferol treatment to reduce blood pressure in older patients with isolated systolic hypertension: the VitDISH randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1672–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hulter HN, Melby JC, Peterson JC, Cooke CR. Chronic continuous PTH infusion results in hypertension in normal subjects. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 1986;2:360–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bosworth C, Sachs MC, Duprez D, et al. Parathyroid hormone and arterial dysfunction in the multi‐ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;79:429–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brown J, de Boer IH, Robinson‐Cohen C, et al. Aldosterone, parathyroid hormone, and the use of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors: the multi‐ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morfis L, Smerdely P, Howes LG. Relationship between serum parathyroid hormone levels in the elderly and 24 h ambulatory blood pressures. J Hypertens. 1997;15:1271–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rydberg E, Birgander M, Bondeson A, et al. Effect of successful parathyroidectomy on 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tomaschitz A, Fahrleitner‐Pammer A, Pieske B, et al. Effect of eplerenone on parathyroid hormone levels in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. BMC Endocr Disord. 2012;13:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tomaschitz A, Pilz S, Rus‐Machan J, et al. Interrelated aldosterone and parathyroid hormone mutually modify cardiovascular mortality risk. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:710–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brown JM, Williams JS, Luther JM, et al. Human interventions to characterize novel relationships between the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system and parathyroid hormone. Hypertension. 2014;63:273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loncar G, Bozic B, Dimkovic S, et al. Association of increased parathyroid hormone with neuroendocrine activation and endothelial dysfunction in elderly men with heart failure. J Endocrinol Invest. 2011;34:e78–e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rutledge MR, Farah V, Adeboye AA, et al. Parathyroid hormone, a crucial mediator of pathologic cardiac remodeling in aldosteronism. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2013;27:161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]