Abstract

Use of ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring (ABPM) allows for identification of dipping, nondipping, extreme dipping, and reverse dipping of BP. Using office BP and ABPM, hypertension subtypes can be identified: sustained normotension (SNT), white‐coat hypertension, masked hypertension, and sustained hypertension. The comparison of hemodynamic parameters and salt intake has not been investigated among these patient groups. Office BP, ABPM, augmentation index (AIx), pulse wave velocity (PWV), cardiac output (CO), and total peripheral resistance (TPR) were automatically measured. Estimation of salt intake was assessed by 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion. Urinary sodium excretion was not different among groups. AIx, PWV, CO, and TPR were lowest in patients with SNT. CO was lowest while AIx adjusted for a heart rate of 75 beats per minute, PWV, and TPR were highest in the extreme dipper group. No relationship was detected between hypertension subtypes and urinary sodium excretion.

Use of ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring (ABPM) allows for identification of four different patterns of the nocturnal BP profile (ie, normal dipping, nondipping, extreme dipping, and reverse dipping). These different BP patterns are associated with different rates of target organ damage and clinical outcome.1, 2 At the same time, by using office (clinical) BP measurements and ABPM, another four group of patients are identifiable: those with (a) sustained normotension (SNT; normal BP in the office and on ABPM); (2) white‐coat hypertension (WCHT; higher clinical BP but normal ABPM values); (3) masked hypertension (MHT; normal clinical BPs but higher ABPM values); and (4) sustained hypertension (SHT; both higher clinical and ABPM values).3

It has been suggested that salt intake is one of the most pivotal environmental factors in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Increased salt intake has been shown to change arterial wall structure and function.4 Therefore, increased sodium intake may result in adverse remodeling of the central and peripheral arterial vasculature that underlies both brachial and central pressure augmentation. Indeed, increased salt intake was associated with arterial stiffness.5, 6, 7 Some studies have also suggested that dipping status is linked to arterial stiffness and salt intake.8, 9, 10 The aims of the current study were:

To compare salt intake measured by 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion among dippers, extreme dippers, nondippers, and reverse dippers and patients with SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT;

To study the relationship between SNT, WHT, MHT, and SHT and dipping patterns;

To compare pulse wave velocity (PWV), augmentation index (AIx), cardiac output (CO), and total peripheral resistance (TPR) among dippers, extreme dippers, nondippers, and reverse dippers and among patients with SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT by specifically adjusting for salt intake.

Materials and Methods

The study had a cross‐sectional design. The participants of this study were from the nephrology outpatient clinic of Selcuk University School of Medicine. The study was in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment. The Selcuk University ethics committee approved the study with the approval number of 130‐47. All patients with essential hypertension attending the nephrology outpatient clinic willing to participate were included. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with secondary hypertension, type 1 diabetes, rhythm and conduction problems, recent history (in past 6 months) of acute coronary syndrome, recent history of stroke, liver disease, obstructive sleep apnea, symptomatic heart failure, urinary tract infection, neurologic disorders, pulmonary and autoimmune diseases, refusal to participate, and night‐shift workers.

The demographic characteristics and medications were collected during anamnesis procedure. Twenty‐four–hour urine specimens were collected to determine creatinine clearance, albumin and protein excretion, and urinary sodium excretion. Urine collection was assessed by predetermined standards.11

Office BP Measurement

Office BP measurements were recorded by Omron MZ model (Omron Health Care, Mukou City, Kyoto, Japan) sphygmomanometer. BPs were measured according to European Society of Hypertension guidelines.12

Ambulatory BP Measurement

Ambulatory BP measurement was performed by Mobil‐O‐Graph Arteriograph (I.E.M. GmbH, Stolberg, Germany) device, which has been validated.13 The device was set to obtain BP readings at 30‐minute intervals during the day (7 am–10 pm) and at 60‐minute intervals during the night (10 pm–7 am). Each ABPM dataset was first automatically scanned to remove artifactual readings according to preselected editing criteria. Each ABPM dataset was first automatically scanned to remove artifactual readings according to preselected editing criteria. Data were edited by omitting all readings of zero, all heart rate readings <30, diastolic BP (DBP) readings >170 mm Hg, systolic BP (SBP) readings >270 mm Hg and <80 mm Hg, and all readings where the difference between SBPs and DBPs was less than 10 mm Hg. Data were visually inspected for gross artifacts. The percentage of total errors was calculated by dividing the number of errors by the total number of measurements in each 24‐hour recording. The recordings with total errors exceeding 10% of the readings were not evaluated.

All patients were instructed to rest or sleep between 10 pm and 7 am (nighttime) and to continue their usual activities between 7 am and 10 pm (daytime).

The definition of SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT were as follows, respectively:

office SBP/DBP <140/90 mm Hg and daytime ABPM <135/85 mm Hg;

office SBP/DBP ≥140/90 mm Hg and daytime ABPM <135/85 mm Hg;

office SBP/DBP <140/90 mm Hg and daytime ABPM ≥135/85 mm Hg; and

office SBP/DBP ≥140/90 mm Hg and daytime ABPM ≥135/85 mm Hg.1

The definition of dippers, extreme dippers, reverse dippers, and nondippers were as follows, respectively:

nighttime systolic and diastolic decline in BP >10% and <20% compared with daytime BP values;

nighttime systolic and diastolic decline in BP >20%;

no reduction or increase in average nighttime systolic and diastolic BP; and

reduction in average nighttime systolic and diastolic BP <10%.14

Measurement of Central BPs, AIx, CO, TPR, and PWV

By using the Mobil‐O‐Graph arteriograph device with an ARC solver method (Austrian Institute of Technology, Vienna), pulse waveforms from the brachial artery were recorded during 24 hours. This method, which has been previously validated,15 oscillometrically captures the pulse waveform from the brachial artery by an upper‐arm cuff. The recordings were carried out at the diastolic pressure level for approximately 10 seconds using a conventional BP cuff and a high‐fidelity pressure sensor (MPX5050, Freescale Inc, Tempe, AZ). The recording time of the oscillometric signal at diastolic level allows the derivation of central hemodynamic parameters, such as central BPs, AIx adjusted for a heart rate of 75 beats per minute (AIx@75), and CO as well as TPR from the pulse waveform by means of a transfer function. Calculation of CO was measured automatically using software using patient‐specific calibration factor, heart rate, compliance, area of pressure curve, and compliance, as described elsewhere.16

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean±standard deviation or as a percentage. Data were analyzed using the program SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Parameter differences among the four groups were evaluated using the Kruskal‐Wallis test. For post hoc analysis of these variables, the Bonferroni‐corrected Mann‐Whitney U test was used. For the comparison of categorical variables, chi‐square test or Fisher exact test was used as appropriate. Adjusted mean scores of 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion were calculated using general linear models and compared with analysis of co‐variance (ANCOVA) between SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT and between dippers, extreme dippers, nondippers, and reverse dippers. These analyses were adjusted for age, sex, hypertension duration, smoking status, presence of type 2 diabetes, presence of coronary artery disease, body mass index (BMI), creatinine clearance, use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, use of angiotensin receptor blocker, use of calcium channel blocker, use of β‐adrenergic blocker, use of α‐adrenergic blocker, use of thiazide diuretic, and use of loop diuretic.

Results

Initially, 269 patients were recruited. One patient with renal artery stenosis, one patient with adrenal mass, four patients with rhythm problems, two patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, seven patients with recent history of acute coronary event, two patients with history of stoke, two patients with chronic liver disease, three patients with obstructive sleep apnea, three patients with symptomatic heart failure, three patients with urinary tract infection, three patients with Alzheimer and dementia, five patients with chronic obstructive lung disease, one patient with rheumatoid arthritis, two patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, eight patients who did not want to participate, and 12 patients whose laboratory data and ABMP data were missing or inappropriate were excluded. The study was performed in the remaining 210 patients. The demographic and laboratory parameters of the included patients are presented in Table 1. The circadian and central BPs, PWV, AIx@75, TPR, and CO are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and Laboratory Variables of 210 Patients With Essential Hypertension

| Parameter | No. or Mean±Standard Deviation |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 57.2±14.0 |

| Sex, male/female | 95/115 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.9±11.2 |

| Smoking, present/absent | 72/138 |

| Presence/absence of type 2 diabetes mellitus | 86/124 |

| Hypertension duration, y | 7.74±4.80 |

| Presence/absence of coronary artery disease | 74/136 |

| Presence/absence of cerebrovascular disease | 12/198 |

| Use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (present/absent) | 35/175 |

| Use of angiotensin receptor blocker (present/absent) | 75/135 |

| Use of calcium channel blocker (present/absent) | 88/122 |

| Use of β‐adrenergic blocker (present/absent) | 49/161 |

| Use of α‐adrenergic blocker (present/absent) | 38/172 |

| Use of thiazide diuretic (present/absent) | 34/176 |

| Use of loop diuretic (present/absent) | 33/177 |

| Use of acetyl salicylic acid (present/absent) | 99/111 |

| Use of statins (present/absent) | 61/149 |

| Office systolic BP, mm Hg | 131.6±17.2 |

| Office diastolic BP, mm Hg | 83.2±11.0 |

| Serum glucose, mmol/L | 6.49±2.50 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 14.5±9.03 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 103.4±49.5 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 134.1±17.9 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 138.9±3.1 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.48±0.47 |

| Albumin, g/L | 41.1±4.7 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.96±1.15 |

| LDL‐C, mmol/L | 3.04±0.95 |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 1.12±0.28 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.83±0.97 |

| Uric acid, μmol/L | 368.2±129.7 |

| Alkaline phospatase, nkat/L | 1.34±0.44 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, nkat/L | 0.37±0.19 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.33±0.15 |

| Phosphorus, mmol/L | 1.14±0.21 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 70.7±28.4 |

| 24‐h urinary protein excretion, mg/d | 694.4±1468.9 |

| 24‐h urinary albumin excretion, mg/d | 388.5±1036.6 |

| 24‐h urinary sodium excretion, mmol/d | 174.6±75.8 |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Table 2.

Circadian and Central BPs, Pulse Wave Velocity, AIx, Total Peripheral Resistance, and Cardiac Output of 210 Patients With Essential Hypertension

| Average ambulatory SBP (daytime), mm Hg a | 127.6±17.9 |

| Average ambulatory DBP (daytime), mm Hg a | 80.3±11.9 |

| Average ambulatory SBP (nighttime), mm Hg a | 121.2±19.1 |

| Average ambulatory DBP (nighttime), mm Hg a | 74.6±13.1 |

| Average ambulatory SBP (24‐h), mm Hg a | 125.9±17.8 |

| Average ambulatory DBP (24‐h), mm Hg a | 78.7±11.8 |

| Mean ambulatory arterial BP (daytime), mm Hg a | 101.9±13.6 |

| Mean ambulatory arterial BP (nighttime), mm Hg a | 95.8±14.9 |

| Mean ambulatory arterial BP (24‐h), mm Hg a | 100.4±13.5 |

| Mean ambulatory heart rate (daytime), beats per min a | 77.4±11.2 |

| Mean ambulatory heart rate (nighttime), beats per min a | 68.3±9.9 |

| Mean ambulatory heart rate (24‐h), beats per min a | 75.0±10.5 |

| Pulse pressure (daytime), mm Hg a | 47.5±12.2 |

| Pulse pressure (nighttime), mm Hg a | 46.8±12.4 |

| Pulse pressure (24‐h), mm Hg a | 47.3±12.0 |

| Central systolic BP (daytime), mm Hg a | 117.7±16.4 |

| Central systolic BP (nighttime), mm Hg a | 113.9±17.3 |

| Central systolic BP (24‐h), mm Hg a | 116.6±16.5 |

| Central diastolic BP (daytime), mm Hg a | 82.2±12.3 |

| Central diastolic BP (nighttime), mm Hg a | 75.7 ±13.6 |

| Central diastolic BP (24‐h), mm Hg a | 80.3±12.2 |

| AIx @75 (daytime), % a | 22.9±10.4 |

| AIx @75 (nighttime), % a | 22.4±13.0 |

| AIx @75 (24‐h), % a | 22.7±10.5 |

| Cardiac output (daytime), L/min a | 4.27±0.58 |

| Cardiac output (nighttime), L/min a | 3.99±0.67 |

| Cardiac output (24‐h), L/min a | 4.22±0.59 |

| Total peripheral resistance (daytime), s.mm Hg/mL a | 1.34±0.17 |

| Total peripheral resistance (nighttime), s.mm Hg/mL a | 1.35±0.22 |

| Total peripheral resistance (24‐h), s.mm Hg/mL a | 1.34±0.18 |

| Pulse wave velocity (daytime), m/s a | 7.82±1.91 |

| Pulse wave velocity (nighttime), m/s a | 7.67±1.93 |

| Pulse wave velocity (24‐h), m/s a | 7.77±1.92 |

Abbreviations: AIx@75, augmentation index adjusted for heart rate of 75; BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure. aMean±standard deviation.

There were 109 (51.9%) patients with SNT, 11 (5.2%) patients with WCHT, 15 (7.1%) patients with MHT, and 75 (35.7%) patients with SHT. A total of 34 (16.2%) patients were dippers, four (1.9%) were extreme dippers, 96 (45.7%) were nondippers, and 76 (36.2%) were reverse dippers.

Among 11 WCHT patients (daytime ABMP <135/85 mm Hg) in our study, five had only increased office SBP (office SBP ≥140 mm Hg but office DBP <90 mm Hg), three had only increased office DBP (office SBP <140 mm Hg but office DBP ≥90 mm Hg), and three had both increased office SBP and office DBP (office SBP ≥140 mm Hg and office DBP ≥90 mm Hg). Among 15 patients with MHT (all with office BP <140/90 mm Hg), six had daytime systolic ABPM ≥135 mm Hg, three had daytime diastolic ABPM ≥85 mm Hg, and six had both daytime systolic and diastolic ABPM ≥135/85 mm Hg.

Among patients with sustained hypertension, 51 had both increased office systolic and diastolic blood pressure, seven had only increased office DBP, and 17 had only increased office SBP. Regarding ABPM in patients with sustained hypertension, 54 had both increased ambulatory SBP and DBP, four had only increased ambulatory diastolic pressure, and 17 had only increased ambulatory SBP.

Among 109 patients with SNT, 47 were using multiple antihypertensive drugs and 62 were using single antihypertensive drugs; among 11 patients with WCHT, six were using multiple antihypertensive drugs and five were using single antihypertensive drugs; among 15 MHT patients, three were using multiple antihypertensive drugs and 12 were using single antihypertensive drugs; and among 75 SHT patients, 34 patients were using multiple antihypertensive drugs and 41 patients were using single antihypertensive drugs. The comparison of multiple‐drug and hypertension subtypes showed no difference (P=.261)

The cross comparison of patients with SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT with dippers, extreme dippers, nondippers, and reverse dippers patients did not demonstrate significant differences (P=.201) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cross Comparison of Patients With SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT With Dippers, Extreme Dippers, Nondippers, and Reverse Dippers

| SNT (n=109) | WCHT (n=11) | MHT (n=15) | SHT (n=75) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dippers (n=34) | 23 | 2 | 0 | 9 | .201 |

| Extreme dippers (n=4) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Nondippers (n=96) | 43 | 5 | 10 | 38 | |

| Reverse dippers (n=76) | 42 | 3 | 5 | 26 |

Abbreviations: MHT, masked hypertension; SHT, sustained hypertension; SNT, sustained normotension; WCHT, white‐coat hypertension.

Among demographic parameters, only sex was different (Table 4) between patients with SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT. None of the other demographic parameters including antihypertensive medication were statistically different (data not shown). The use of antihypertensive medication among patients with SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT were shown in Table 5

Table 4.

Statistically Different Demographic, Laboratory, and Hemodynamic Parameters Among SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT

| SNT (Group I) | WCHT (Group II) | MHT (Group III) | SHT (Group IV) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women/men, No. | 65/44IV | 9/2IV | 8/7 | 33/42I,II | .043 |

| 24‐h UAE | 184.2±492.1IV | 105.6±205.9IV | 231.2±412.3 | 755.5±1555.0I,II | .005 |

| Uric acid | 6.01±2.29 | 4.94±1.27III,IV | 7.05±2.29II | 6.5±2.0II | .044 |

| AIx@75 (daytime) | 20.7±10.7II,III,IV | 27.3±8.7I | 24.5±10.0I | 25.1±9.8I | .005 |

| AIx@75 (nighttime) | 19.7±12.5III,IV | 25.5±13.3 | 27.5±14.0I | 25.0±12.9I | .003 |

| AIx@75 (24‐h) | 20.4±10.5II,III.IV | 26.8±9.5I | 25.2±10.4I | 25.0±10.2I | .003 |

| PWV (daytime) | 7.27±1.70II,IV | 8.61±2.57I | 8.15±1.74 | 8.44±1.93I | <.0001 |

| PWV (nighttime) | 7.15±1.69II,IV | 8.36±2.45I | 8.09±1.80 | 8.23±2.04I | .002 |

| PWV (24‐h) | 7.23±1.70II | 8.52±2.50I | 8.11±1.77 | 8.38±1.97 | .001 |

| CO (daytime) | 4.1±0.51III,IV | 4.28±0.46 | 4.35±0.34I | 4.52±0.67I | <.0001 |

| CO (24‐h) | 4.08±0.56IV | 4.19±0.57 | 4.28±0.32 | 4.39±0.65I | .003 |

| TPR (daytime) | 1.25±0.12II,III,IV | 1.35±0.11I,IV | 1.35±0.12I,IV | 1.46±0.18I,II,III | <.0001 |

| TPR (nighttime) | 1.24±0.18III,IV | 1.34±0.20IV | 1.42±0.16I | 1.49±0.23I,II | <.0001 |

| TPR (24‐h) | 1.25±0.13II,III,IV | 1.34±0.14I,IV | 1.38±0.11I | 1.46±0.19I,II | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: AIx, augmentation index; CO, cardiac output; MHT, masked hypertension; PWV, pulse wave velocity; SHT, sustained hypertension; SNT, sustained normotension; TPR, total peripheral resistance; UAE, urinary albumin excretion; WCHT, white‐coat hypertension. P value is based on Kruskal‐Wallis test (groups with significant differences according to post hoc testing are shown in superscript roman numerals).

Table 5.

The Detailed Antihypertensive Use Among Different Hypertensive Subtypes

| Medications Used | SNT | WCHT | MHT | SHT | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitor | 18 (16.5) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (6.7) | 12 (16) | .243 |

| ARB | 41 (37.6) | 3 (27.3) | 4 (26.7) | 27 (36.0) | .789 |

| β‐Blocker | 25 (22.9) | 1 (9.1) | 4 (26.7) | 19 (25.3) | .678 |

| α‐Blocker | 21 (19.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (6.7) | 15 (20) | .530 |

| CCB | 45 (41.3) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (26.7) | 34 (45.3) | .600 |

| Thiazide diuretic | 18 (17.6) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (6.7) | 12 (16) | .571 |

| Loop diuretic | 16 (14.7) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (6.7) | 12 (16) | .243 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; MHT, masked hypertension; SHT, sustained hypertension; SNT, sustained normotension; WCHT, white‐coat hypertension.

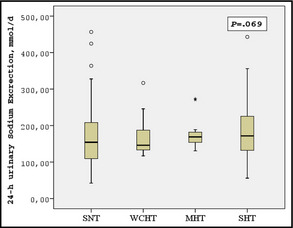

Comparison of laboratory parameters among patients with SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT showed that urinary albumin excretion (P=.005) and uric acid (P=.044) were different among groups (Table 4). Fasting blood glucose (P=.057) and high‐density lipoprotein (P=.055) also tended to be different. Urinary sodium excretion was not different among groups (P=.069) (Figure 1). Among hemodynamic parameters, AIx@75 (24 hours), AIx@75 (daytime), AIx@75 (nighttime), PWV (24 hours), PWV (daytime), PWV (nighttime), CO (24 hours), CO (daytime), TPR (24 hours), TPR daytime, and TPR (nighttime) were different among these groups (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Comparison of 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion among patients with sustained normotension (SNT), white‐coat hypertension (WCHT), masked hypertension (MHT), and sustained hypertension (SHT).

Twenty‐four–hour urinary sodium excretion was not different among dipper, extreme dipper, nondipper, and reverse dipper patients (P=.990). Comparison of laboratory parameters showed that only uric acid levels (P=.035) were different among these groups (Table 6). Urinary sodium excretion was not different among these categories (P=.804). Among other parameters (apart from routine ABPM), CO (24 hours), CO (daytime), CO nighttime, AIx@75 (nighttime), PWV (nighttime), and TPR (nighttime) were different among these groups (Table 6).

Table 6.

Statistically Different Demographic, Laboratory, and Hemodynamic Parameters Among Dippers, Extreme Dippers, Nondippers, and Reverse Dippers

| Dippers (Group I) | Extreme Dippers (Group II) | Nondippers (Group III) | Reverse Dippers (Group IV) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid | 5.59±2.40III | 5.10±1.06III | 6.73±2.36I,II | 5.88±1.72 | .035 |

| CO (daytime) | 4.27±0.61 | 3.85±0.34III | 4.37±0.53II,IV | 4.17±0.64III | .019 |

| CO (nightime) | 3.76±0.78III,IV | 3.13±0.60III,IV | 4.05±0.61I,II | 4.08±0.66I,II | .016 |

| CO (24‐h) | 4.13±0.62 | 3.63±0.39III,IV | 4.28±0.53II | 4.20±0.65II | .041 |

| AIx@75 (night) | 17.5±13.9II,IV | 27.5±6.99I | 20.8±12.3 | 26.4±12.8I | .007 |

| PWV (night) | 7.11±1.43II,IV | 8.73±1.09I,III | 7.45±2.0II,IV | 8.14±1.98I,III | .020 |

| TPR (night) | 1.27±0.19II,IV | 1.47±0.17I | 1.33±0.20IV | 1.41±0.27I,III | .01 |

Abbreviations: AIx@75, augmentation index adjusted for heart rate of 75 beats per minute; CO, cardiac output; PWV, pulse wave velocity; TPR, total peripheral resistance. P value is based on Kruskal‐Wallis test (groups with significant differences according to post hoc testing are shown in superscript roman numerals).

Lastly, adjusted mean scores of 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion were calculated using general linear models and compared with ANCOVA between SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT and between dippers, extreme dippers, nondippers, and reverse dippers. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, hypertension duration, smoking status, presence of type 2 diabetes, presence of coronary artery disease, BMI, creatinine clearance, use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, use of angiotensin receptor blocker, use of calcium channel blocker, use of β‐adrenergic blocker, use of α‐adrenergic blocker, use of thiazide diuretic, and use of loop diuretic. The results of ANCOVA showed that there was no statistical difference with respect to 24‐hour sodium excretion among patients with SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT (P=.091). Adjusted 24‐hour sodium excretion was also not different between dippers, extreme dippers, nondippers, and reverse dippers by the ANCOVA statistic (P=.479).

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated different BP patterns (related to dipping) and BP patient phenotypes (normal vs sustained hypertension vs white‐coat hypertension vs masked hypertension) in relation to demographic, laboratory, and vascular/hemodynamic parameters, particularly urinary sodium excretion. As a result of our study, some novel findings emerged. First, we demonstrated that there was no significant difference with respect to dipping profile among patients with various BP phenotypes (SNT, MHT, WCHT, and SHT). However, uric acid, 24‐hour urinary albumin excretion, AIx@75, PWV, CO, and TPR were significantly different among patients with SNT, MHT, WCHT, and SHT. At the same time, uric acid, AIx@75, PWV, CO, and TPR were different among dippers, extreme dippers, nondippers, and reverse dippers. Particularly, extreme dippers had the lowest CO and highest AIx@75, PWV, and TPR—despite previously published data showing that such a phenotype is associated with a beneficial outcome. Lastly, there was no difference with respect to 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion among hypertension subgroups and different dipping profiles, after adjusting for potential covariates.

It has been previously shown that different BP patterns are associated with different rates of target organ damage and clinical outcome. Thus, it is concluded that use of ABPM is beneficial and may give prognostic information beyond office BP measurements.1, 2 Our study confirms that a significant proportion of patients were treated successfully have in fact abnormal BP patterns: several patients with normal mean office SBP and mean office DBP were in fact re‐classified as having SHT based on ABPM. In addition, by using ABPM, 96 patients were found to be nondippers and 76 reverse dippers. Thus, even if BP seems to be well controlled, use of only clinical BP may not be enough given the fact that hypertension types and dipping patterns are related to cardiovascular outcomes.

In the present study, although patients with SHT were predominantly nondippers and reverse dippers, this trend did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). The lack of an association between dipping patterns and hypertension phenotype may have several explanations. First, antihypertensive medications could influence the results. However, there are no differences with respect to medications among the different hypertension types/dipping profiles. Second, there were few patients with an extreme dipping pattern, which may impact our findings. Last, different pathophysiologic mechanisms may be responsible for hypertension types (SNT, WCHT, MHT, and SHT) and for dipping patterns.

The current study demonstrated that AIx@75, PWV, TPR, and CO were lowest in the SNT group. Since BP is the product of CO and TPR, our findings are expected. However, the surprising and unexpected findings for us were the higher AIx@75, PWV, TPR, and lower CO levels in extreme dippers. Previous studies reported contrasting findings with regard to dipping pattern and arterial stiffness.8, 9, 17 Recently, the relationship between PWV and dipper status was found to be J‐shaped, with extreme dippers and reverse dippers having the highest PWV18––very similar to our findings. Grassi and colleagues19 demonstrated that muscle sympathetic nerve traffic was significantly higher in hypertensive nondippers, dippers, and extreme dippers than in normotensive controls. In addition, a significant further increase was detected in reverse dippers compared with all other groups. The authors concluded that the reverse dipping state is characterized by a sympathetic activation greater than that seen in other conditions, displaying abnormalities in nighttime BP pattern.19 Increased activation of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system was also suggested to occur in reverse hypertensive patients.20 Thus, all these factors might lead to increased central hemodynamic parameters such as TPR, PWV, and AIx@75 in reverse dipper patients. Nevertheless, the higher AIx@75, PWV, and TPR and lower CO levels found in extreme dippers in our study may be potential explanations for adverse findings in patients with extreme dipping. More studies are needed to highlight these issues.

In the current study, we found no difference between hypertension subtypes, dipping patterns, and 24‐hour urinary sodium excretion, which is accepted as the most accurate indirect method of determining salt consumption.21 In addition, none of the hemodynamic parameters including PWV, AIx@75, TPR, and CO were significantly correlated with urinary sodium excretion (data not shown). Studies addressing this issue are conflicting. While some studies reported a positive association between urinary sodium excretion and arterial stiffness parameters,5, 7 others have failed to demonstrate any relationship.22 Various covariates may affect sodium excretion. To minimize these effects, we also adjusted these parameters while comparing sodium excretion among groups (ANCOVA).

Study Limitations

This study has some potential limitations. First, we included mostly patients in whom BP was relatively well controlled. Thus, our findings cannot be generalized, especially when taking into account patients with more severe hypertension. Moreover, our patient population was relatively obese and this might influence the results. Second, patients were treated for hypertension and drugs may influence the results. However, there was no difference with respect to medications used, and we made adjustment for various covariates while comparing sodium excretion, which was one of the specific aims of the study. We believe that these facts decrease, but does not exclude, the possibility of the treatment's influence. In addition, routine daily practice was thus investigated. Third, the classification of the circadian BP pattern with a single ABPM could be inaccurate because of its lower reproducibility. However, authors using a single ABPM also demonstrated a relationship between nondipping status and target organ damage.23, 24 Besides, the extreme pattern of diurnal BP variations in extreme dippers or reverse dippers is a relatively persistent trait. Fourth, the effects of menopause and oral contraceptives were not evaluated specifically. Last, since the study used a cross‐sectional design, cause‐and‐effect relationships cannot be suggested.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that different hypertension subtypes (SNT, WCHT, MHT, SHT) and dipping status are not related to each other and urinary sodium excretion does not differ among groups. On the other hand, most of the hemodynamic parameters were different among these groups. More studies are needed to highlight the pathophysiologic mechanisms regarding hypertension subtypes and dipping status and their influence on cardiovascular outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Nothing to declare.

Disclosure

The authors report no specific funding in relation to this research and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015;17:200–206. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12464. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. O'Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, et al. European Society of Hypertension recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and home blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2003;21:821–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood‐pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2368–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bobrie G, Clerson P, Ménard J, et al. Masked hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1715–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Cavanagh EMV, Ferder LF, Ferder MD, et al. Vascular structure and oxidative stress in salt‐loaded spontaneously hypertensive rats: effects of losartan and atenolol. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:1318–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park S, Park JB, Lakatta EG. Association of central hemodynamics with estimated 24‐h urinary sodium in patients with hypertension. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1502–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He FJ, Marciniak M, Visagie E, et al. Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure, urinary albumin, and pulse wave velocity in white, black and Asian mild hypertensives. Hypertension. 2009;54:482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hummel SL, Seymour EM, Brook RD, et al. Low‐sodium dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet reduces blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and oxidative stress in hypertensive heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Hypertension. 2012;60:1200–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lekakis JP, Zakopoulos NA, Protogerou AD, et al. Arterial stiffness assessed by pulse wave analysis in essential hypertension: relation to 24‐h blood pressure profile. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102:391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Asmar R, Scuteri A, Topouchian J, et al. Arterial distensibility and circadian blood pressure variability. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1:333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sachdeva A, Weder AB. Nocturnal sodium excretion, blood pressure dipping, and sodium sensitivity. Hypertension. 2006;48:527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Junge W, Wilke B, Halabi A, Klein G. Determination of reference intervals for serum creatinine, creatinine excretion and creatinine clearance with an enzymatic and a modified Jaffe method. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;2:137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wei W, Tölle M, Zidek W, van der Giet M. Validation of the Mobil‐O‐Graph: 24 h‐blood pressure measurement device. Blood Press Monit. 2010;15:225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Brien E, Sheridan J, O'Malley K. Dippers and non‐dippers. Lancet. 1988;2:397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wassertheurer S, Kropf J, Weber T, et al. A new oscillometric method for pulse wave analysis: comparison with a common tonometric method. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wassertheurer S, Mayer C, Breitenecker F. Modeling arterial and left ventricular coupling for non‐invasive measurements. Simul Model Pract Theory. 2008;16:988–997. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grandi AM, Broggi R, Jessula A, et al. Relation of extent of nocturnal blood pressure decrease to cardiovascular remodeling in never‐treated patients with essential hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1193–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jerrard‐Dunne P, Mahmud A, Feely J. Circadian blood pressure variation: relationship between dipper status and measures of arterial stiffness. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grassi G, Seravalle G, Quarti‐Trevano F, et al. Adrenergic, metabolic, and reflex abnormalities in reverse and extreme dipper hypertensives. Hypertension. 2008;52:925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ivanovic BA, Tadic MV, Celic VP. To dip or not to dip? The unique relationship between different blood pressure patterns and cardiac function and structure. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frost CD, Law MR, Wald NJ. By how much does dietary salt reduction lower blood pressure? II‐Analysis of observational data within populations. BMJ. 1991;302:815–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cuspidi C, Macca G, Sampieri L, et al. Target organ damage and non‐ dipping pattern defined by two sessions of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in recently diagnosed essential hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1539–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. García‐Ortiz L, Gómez‐Marcos MA, Martín‐Moreiras J, et al. Pulse pressure and nocturnal fall in blood pressure are predictors of vascular, cardiac and renal target organ damage in hypertensive patients (LOD‐RISK study). Blood Press Monit. 2009;14:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kario K, Matsuo T, Shimada K. Follow‐up of white‐coat hypertension in the Hanshin‐Awaji earthquake. Lancet. 1996;347:626–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]