Abstract

Despite good evidence regarding the benefits of managing hypertension in elderly populations, the extent to which this evidence has been incorporated into national and international clinical hypertension treatment guidelines is unknown. A systematic review was conducted to identify recommendations in current national and international hypertension treatment guidelines with a focus on specific targets and treatment recommendations for older persons with uncomplicated hypertension. Guidelines for the management of hypertension published or updated over a 5‐year period (2009–2014) were identified by searching Medline, Google, and Google Scholar. Thirteen guidelines that met the predefined inclusion criteria were included in the review. Among these guidelines was considerable variation regarding who is considered an older person. However, there was general consensus regarding blood pressure targets. While current hypertension guidelines do include recommendations regarding management of uncomplicated hypertension in older populations, the depth and breadth of these recommendations vary considerably between guidelines and may limit the usefulness of such treatment guidelines to clinicians.

Hypertension is the leading modifiable cause of mortality worldwide.1 As with many conditions, hypertension increases with age and is a common condition in older persons. The Framingham Heart Study reported that the prevalence of hypertension increased from 27.3% in patients aged younger than 60 years to 74.0% in those aged older than 80 years, demonstrating the age‐related nature of hypertension.2

While older populations are often excluded from clinical trials for many conditions,3 a number of large, well‐designed trials exploring hypertension in older persons have been conducted.4, 5, 6 A Cochrane review published in 2009 reported 15 studies (n=24,055 patients) exploring the management of hypertension in those older than 60 years.7 These findings demonstrated the considerable benefits of actively managing hypertension among older persons, as well as provided evidence regarding appropriate blood pressure (BP) targets and pharmacotherapy for this population.

Establishing the evidence is the first step in ensuring optimal patient care, yet it is well documented that there is a considerable lag in the translation of scientific evidence into current clinical practice. Moreover, incorporating the latest evidence into daily practice is something many physicians often find problematic.8 One strategy aimed at minimizing the evidence‐practice gap is the development and implementation of evidence‐based guidelines. Guidelines have the potential to improve care and patient outcomes9 and multiple guidelines for the management of hypertension exist at both national and international levels. While there are many guidelines concerned with the management of hypertension in general, there are considerable differences between guidelines with respect to the focus and included content.10

Management of hypertension in older persons is one area in which there appears to be considerable differences between guidelines in terms of the guidance given to clinicians. Differences in interpretation of the evidence, as well as differences in study design and included populations all contribute to differences in the guideline treatment recommendations with respect to older populations, despite the strength of the underlying scientific evidence. Differences around who is considered “elderly” or “older” and what BP targets and pharmacologic management are considered appropriate may lead to confusion among clinicians and further contribute to the evidence‐practice lag. The aim of this study was to review recommendations regarding the management of uncomplicated hypertension in older populations in current national and international hypertension treatment guidelines with a focus on specific targets and treatment recommendations for older persons with uncomplicated hypertension.

Methods

Literature Search

Guidelines for the management of hypertension were identified by searching Medline (via Ovid) Subject Heading (MeSH) terms: “hypertension” and “guideline.” In addition, the Internet was searched via Google and Google Scholar for additional guidelines using the query “guidelines for management of hypertension.” This search strategy has been used in previous studies to identify national and international treatment guidelines for hypertension.11 In addition, Web sites from societies and professional bodies who publish treatment guidelines for the management of hypertension were also searched. To ensure that the most recent guidelines were included in the review, the search was limited to guidelines published between January 2009 and December 2014.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All guidelines published or updated between 2009 and 2014 were included. Guidelines published in languages other than English were excluded. Since we were interested in guideline recommendations for older individuals, consensus or advisory documents as well as guidelines for the management of hypertension in specific populations such as pediatrics and pregnancy were excluded from the study.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures considered in this study were:

Does the guideline contain an explicit definition of who is considered older or elderly?

Does the guideline explicitly define hypertension, in terms of BP, in older persons?

Does the guideline contain explicit recommendations regarding BP at which pharmacotherapy should be commenced for older persons with uncomplicated hypertension?

What pharmacologic agents are explicitly recommended for initial treatment of uncomplicated hypertension in the elderly?

Does the guideline contain explicit BP treatment target recommendations in older persons with uncomplicated hypertension?

Definitions

In the context of this study, any recommendations regarding the older or elderly persons had to be explicitly stated in the guideline. Guidelines that did not include explicit statements regarding the above outcomes for “elderly” or “older” populations were considered to not include the older populations for that characteristic. Guidelines that explicitly stated that older persons were to be managed in the same manner with respect to treatment or BP levels as younger populations were considered to explicitly deal with older persons.

Data Extraction

Data relevant to the defined study outcomes were extracted from each guideline. The first and last authors of this review conducted assessment of outcome measures independently. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached.

Results

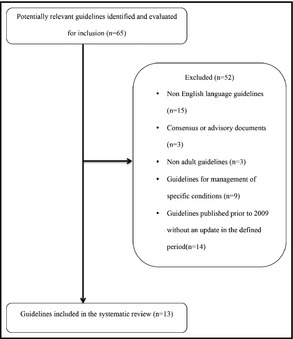

Using the search strategy outlined, 65 guidelines that met the initial criteria were identified. Of these, 52 were excluded according to the exclusion criteria (Figure), leaving 13 guidelines included in this review. The guidelines included in this review covered a variety of geographical regions. Five guidelines represented clinical practice in the Americas (four from North America,12, 13, 14, 15 one from Latin America16), two in Europe,17, 18 two in Asia,19, 20 one in Africa,21 one in Oceania22 (Australia, New Zealand, and surrounding islands), and two in the Middle East23, 24 (Table). No guidelines specifically dedicated to the management of hypertension in the elderly were found.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and inclusion of studies.

Table 1.

Summary and Characteristics of Guidelines Included in the Review

| Guideline | Year, Country | Definition of Older Population (Age) | Inclusion of Explicit BP Target for Defining Uncomplicated Hypertension in Older Populations | Target BP Specified for Initiation of Pharmacotherapy in Older Populations | Recommendations for First‐Line Drug Therapy for the Management of Uncomplicated Hypertension in Older Populations | Treatment BP Target for Older Populations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JNC 814 | 2014, United States | ≥60 y | No | SBP ≥150 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg | Thiazide, CCB, ACE, ARB | SBP <150 mm Hg and DBP <90 mm Hg |

| ESC18 | 2013, Europe | <80 y | Yes | SBP ≥140 mm Hg | Thiazide, CCB, ACE, ARB | SBP <150 mm Hga |

| ≥80 y | SBP ≥160 mm Hg | Thiazide, CCB, ACE, ARB | SBP <150 mm Hga | |||

| NICE17 | 2011, United Kingdom | <80 y | No | SBP ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg | SBP <140 mm Hg and DBP <90 mm Hg | |

| ≥80 y | SBP ≥160 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥100 mm Hg | Same as those aged 55–80 y | SBP <150 mm Hg and DBP <90 mm Hg | |||

| ASH/ISH12 | 2013, United States | ≥80 y | Yes | SBP ≥150 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg | Thiazideb or CCB | 150/90 mm Hg |

| CHEP13 | 2014, Canada | ≥80 y | No | SBP ≥160 mm Hg | – | SBP <150 mm Hgd |

| ICSI15 | 2012, United States | ≥60 y | Yes | SBP >160 mm Hg | Thiazideb or dihydropyramide CCB | <150 mm Hg |

| HF22 | 2010, Australia | ≥65 y | No | – | Thiazideb | – |

| JSH19 | 2014, Japan | Yes | ≥140/90 mm Hg | Thiazideb diuretics, CCBs, ACE inhibitors, or ARBs | SBP <140 mm Hg/DBP <90 mm Hg (65–74 y) SBP <150 mm Hg (≥75 y) | |

| LA16 | 2009, Latin America | ≥65 y | No | – | Thiazide or dihydropyridine CCB | <140/90 mm Hg |

| SAHS21 | 2011, South Africa | – | No | – | Thiazide or dihydropyridine CCB | – |

| TAIWAN20 | 2015, Taiwan | <80 y | No | SBP ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg | <140/90 mm Hg | |

| ≥80 y | SBP ≥150 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg | – | <150/90 mm Hg | |||

| SHMS23 | 2011, Saudi Arabia | ≥65 y | Yes | – | Thiazideb | <140/90 mm Hg |

| EG24 | 2014, Egypt | ≥65 y | No | SBP ≥150 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥95 mm Hg | Thiazide or dihydropyridine CCB | <150/95 mm Hg |

| ≥80 y | SBP ≥160 mm Hg |

Abbreviations: ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; CCB, calcium channel blocker; DBP, diastolic blood pressure. See text for guideline abbreviations. aSystolic blood pressure (SBP) <140 mm Hg if treatment is well tolerated in fit elderly patients. bIncludes thiazide‐like diuretics. cBlood pressure (BP) <140/90 mm Hg in patients younger than 80 years. dOriginal version published in 2008, and update published in 2010.

Who is Older?

Three different criteria were used within the guidelines to identify and define older populations. Just under half of the guidelines (n=6) defined the elderly as those aged 80 years or older (Table). Four guidelines used 65 years as the criteria and two 60 years. While the Japanese guideline (Japanese Society of Hypertension [JSH]) discussed management of the elderly in great detail, dedicating a whole chapter to the discussion, no explicit definition was given to what age was considered elderly within the guideline. In the American Society of Hypertension/International Society of Hypertension (ASH/ISH) guideline, recommendations were given for the “middle‐aged to elderly population,” which was defined as 55 to 80 years. Only the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and National Institute of Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines referred explicitly to the needs among different older age groups with different recommendations for those older than and those younger than 80 years. While a number of guidelines defined the elderly as those aged older than 80 years, both the Canadian and Taiwanese guidelines referred to those aged older than 80 years as “very elderly” while the Egyptian guidelines (EG) referred to those older than 80 as “octogenarians.”

What is Considered Hypertension in the Older Person?

Fewer than half of the guidelines gave an explicit definition of hypertension for older populations. For guidelines that did define hypertension, there was consensus that a higher BP reading was less acceptable in younger patients than in older patients; however, there was some variation in the systolic BP considered to represent hypertension in older populations. The majority of guidelines that defined hypertension in older persons considered a BP reading of 140/90 mm Hg consistent with hypertension. Only two guidelines differed, with the ASH/ISH and EG guidelines specifying a slightly higher BP of 150/90 mm Hg. These differences in the definitions of hypertension did not appear to be related to the age of the populations included.

Specific Treatment Recommendations

BP Targets for Initiation of Therapy

Around half of the guidelines did not provide explicit guidance in terms of BP control for commencement of treatment in older persons. For guidelines that did specify initiation targets, there was variation in the BP levels at which treatment should be considered for older persons. While most of the guidelines considered therapy initiation in terms of systolic BP, four guidelines (the 2014 American Eighth Joint National Committee panel guideline [JNC 8], NICE, ASH/ISH, and JSH) provided specific recommendations in terms of diastolic BP. In general, treatment initiation targets were higher than those recommended for nonelderly populations. Only the JNC 8 discussed the uncertainty regarding the evidence for initiation of management in patients older than 80 years.

Management and Pharmacotherapy for Uncomplicated Hypertension in Older Persons

While all the guidelines discussed lifestyle modification as first‐line management for nonelderly populations, only the JSH discussed implementing lifestyle modification specifically in the elderly. In terms of pharmacotherapy, the Canadian Hypertension Education Project (CHEP) guideline did not make any specific recommendations for the management of uncomplicated hypertension in older persons. Both the United Kingdom NICE guideline and the Taiwanese guideline explicitly stated first‐line pharmacotherapy for persons older than 80 years should be the same as that for those aged 55 to 80 years, while the remainder provided specific recommendations for initiation of therapy for uncomplicated hypertension in older populations. Some variation was found in the choice of agent. Thiazide diuretics (and thiazide‐like diuretics) and calcium channel blockers (CCB) were recommended as first‐line therapy for the elderly in most guidelines; however, a number of guidelines further specified that the dihydropyridine CCBs were preferred for older persons. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) were also proposed as equally effective first‐line therapy in a number of guidelines (Table).

Although the majority of guidelines provided guidance regarding first‐line agents for older populations, some guidance was also provided regarding agents that should not be considered in the elderly. The CHEP, Saudi Arabian (SHMS), and EG guidelines explicitly stated that β‐blockers should not be considered in elderly patients, and the Taiwanese guidelines recommend that atenolol, in particular, should not be used for patients 60 years and older.

Awareness of treatment tolerability or increased likelihood of adverse effects in older persons with hypertension were mentioned in a number of guidelines with respect to using pharmacotherapy in older persons. Most guidelines recommended dose adjustment if pharmacotherapy was not tolerated. The ESC guideline recommends consideration of treatment tolerability when treating either frail older persons or those older than 80 years. The Latin American (LA) guidelines recommend that antihypertensive medications be initiated at low doses and then adjusted every 4 to 6 weeks after evaluating side effects, while the EG and JSH guidelines recommended starting at lower doses and avoidance of centrally acting agents. Only the SHMS and CHEP guidelines specifically mentioned an increased risk of orthostatic hypertension and falls with antihypertensive use in older persons.

Treatment Targets

Most guidelines, with the exception of the South African (SAHS) and the Australian (HF) guidelines, gave explicit BP targets for managing hypertension in older populations. In all of the guidelines where explicit targets were given, higher targets were specified for older persons than for nonelderly populations.

Approximately half of the guidelines (n=6) recommended a treatment target for older persons of <150 mm Hg, while five guidelines supported treatment targets of 140 mm Hg (Table). Treatment target recommendations did not appear related to age, with half of the guidelines recommending the higher target were aimed at patients aged 65 years and older, while the remaining half were targeting those aged 80 years and older. Likewise, of those with a target of 140/90 mm Hg, two were recommendations for patients aged 65 years and older, one for patients aged 75 years and older, and two for patients 80 years and older. Three guidelines (the 2014 JSH guideline, the 2011 NICE guidelines, and the 2015 Taiwanese guideline) recommended different treatment targets for different age groups proposing targets. The JSH guideline recommends systolic targets of 140 mm Hg for older populations aged 65 years and younger, and the higher target of 150 mm Hg for populations aged 75 years and older. The NICE guideline and the Taiwanese guideline both propose the lower target for those younger than 80 years and the higher target for those older than 80. With the exception of the Japanese guideline, all of the guidelines recommending treatment targets of <140 mm Hg were published prior to 2012.

Discussion

Specific information regarding the diagnosis and management of uncomplicated hypertension in the elderly is included in all hypertension guidelines considered in this review; however, there is considerable and notable variation in the depth and scope of the recommendations. Such variation was also recently reported in a review of recommendations of general hypertension guidelines.25 Notwithstanding the evidence generated by numerous large well‐designed studies supporting active management of hypertension in older persons, no national or international guidelines specifically dedicated to the management of hypertension in the elderly were found.

While all of the guidelines in this review provided some guidance regarding management of uncomplicated hypertension in older populations, there was considerable variation in what was considered older and how the management of older individuals differed from that of younger populations. Such variation may reflect age differences in study populations. The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET4) recruited participants older than 80 years, while the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly (SHEP)26 study recruited those older than 60 years and the Swedish Trial in Old Patients With Hypertension (STOP)6 recruited those aged between 70 and 84 years. Given global increases in life expectancy, there is a need to reconsider how we define “older” populations as well as a need to ensure that they are represented in clinical trials.

In general, there was consistency across all guidelines regarding recommendations that treatment be commenced in older individuals when systolic BP readings were >140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and treatment titrated to achieve a target BP at the same level. However, despite the guideline recommendations, debate continues regarding optimal BP targets in the elderly. Two Japanese studies, the Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients (JATOS)27 and Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension Study (VALISH)28 both failed to show an additional benefit in treating elderly individuals to a target of 140 mm Hg systolic compared with a target of 160 mm Hg, highlighting the clinical uncertainty in this area.

Identification of a BP target for older populations has been an area of great controversy commencing with publication of the JNC 8 panelist guideline in 2014. One main difference between the 2003 Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) guideline,29 endorsed by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the 2014 JNC 8 guideline concerns treatment targets for older populations. The JNC 7 guideline recommends a tighter target of 140/90 mm Hg for older populations based on clinical trial evidence, while the JNC 8 guideline recommends a higher target of 150/90 mm Hg based on expert opinion. The three trials upon which the higher recommendation of 150/90 mm Hg was made (SHEP,5 Syst‐Eur,30 and HYVET4) all showed lower event rates with active treatment; however, this was against placebo not against a lower treatment target of 140/90 mm Hg and no suitably powered comparison between the two targets has been conducted in older populations.31 Following publication of the higher target by the JNC 8 panelists, five of the original panel members published a refutation, outlining potential risks and lack of clinical trial evidence supporting the higher target. It is also important to note that while the JNC 8 guideline was published, it was not endorsed by the NHLBI31 based on the uncertainty regarding optimal targets for older populations. Clearly, further trials exploring the optimal BP targets are needed before robust conclusions can be drawn.

While no national or international treatment guidelines specifically targeting older populations were found during this review, an Expert Consensus Document on Hypertension in the Elderly was published by the American Society of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association in 2011.32 Being a consensus document rather than a clinical guideline, this work did not meet the inclusion criteria for the current review; however, it has a comparable role informing and guiding clinicians in daily practice.32 While the consensus document recommends a BP treatment target of <140/90 mm Hg, it is clearly stated that this recommendation is based on expert opinion rather than clinical trial data, and that it is unclear whether the one target should be used for all elderly persons.

All guidelines supported the use of pharmacotherapy for the management of hypertension in the elderly reflecting the findings of a 2008 meta‐analysis that concluded that the benefits of pharmacotherapy for managing hypertension in older individuals is comparable to that in younger persons.33 There was considerable variation between guidelines regarding recommended drug therapy for the management of uncomplicated hypertension in older persons. Such variation is likely to reflect differences in the evidence upon which the guideline recommendations were based. There is good evidence for all classes of pharmacotherapy in the management of hypertension in the elderly. Interestingly, while there is some evidence for the use of β‐blockers in the management of hypertension in the elderly34, 35 no guideline recommended first‐line use in older persons and one guideline explicitly mentioned they were not to be used as first‐line agents, which may reflect concerns regarding inadequate risk reduction for stroke in the elderly36, 37 or their potential adverse effect profile in this population.

While most guidelines mentioned that tolerability of pharmacotherapy may be an issue for older persons, only two guidelines in this review discussed specific adverse effects in the elderly such as orthostatic hypertension or falls. Antihypertensive medications have been linked with adverse outcomes in a number of studies39, 40 and more work is needed to fully understand the risks associated with antihypertensive pharmacotherapy in older persons.

Study Limitations

One limitation of this study was the exclusion of non–English language guidelines. Since hypertension is commonly managed in general practice, guidelines should be available in languages relevant to local health professionals.41 Another limitation of this study concerns the inclusion of those studies that are publically available via electronic media. This would have resulted in the exclusion of guidelines that may be available only in a paper‐based format. However, despite these limitations, guidelines from a wide geographical area were included and it is unlikely that exclusion of paper‐based and non–English language guidelines affects the validity of these findings. Similar findings regarding lack of consistency and variation within practice guidelines has been reported across multiple specialty areas. A Canadian study found variation in the applicability of guidelines regarding management of older populations for a number of chronic conditions.42

Conclusions

The results of this review highlight the lack of consistency regarding recommendations for management of hypertension in the elderly despite the strength of the underlying scientific evidence for the management of hypertension in elderly.42, 43, 44 Guidelines have the potential to improve care and patient outcome with an important role in aiding clinicians in the uptake of research findings and incorporation of new knowledge in daily practice. While guidelines are a valuable tool for clinical practice, inconsistencies and variation between guidelines regarding management of hypertension in the elderly may limit their use in daily practice. The current hypertension guidelines included in this review do include recommendations regarding management of hypertension in the elderly; however, the depth and breadth of these recommendations varies between guidelines and may limit their usefulness to clinicians. Given the increases in life expectancy seen in much of the world and the aging of the population, there is a critical need for hypertension guidelines that focus specifically on the management of older persons with hypertension.

Disclosures

The authors report no specific funding in relation to this research and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015;17:486–492. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12536. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Pimenta E, Oparil S. Management of hypertension in the elderly. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Evans JC, Levy D. Hypertension in adults across the age spectrum: current outcomes and control in the community. JAMA. 2005;294:466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hall W. Representation of blacks, women, and the very elderly (aged> or= 80) in 28 major randomized clinical trials. Ethn Dis. 1998;9:333–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beckett NS, Peters R, Bulpitt C, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. SHEP Cooperative Research Group . Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dahlof B, Hansson L, Lindholm L, et al. STOP‐hypertension: Swedish trial in old patients with hypertension. J Hypertens. 1986;4:511–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Musini VM, Tejani AM, Bassett K, et al. Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spranger CB, Ries AJ, Berge CA, et al. Identifying gaps between guidelines and clinical practice in the evaluation and treatment of patients with hypertension. Am J Med. 2004;117:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kjeldsen S, Feldman RD, Lisheng L, et al. Updated national and international hypertension guidelines: a review of current recommendations. Drugs. 2014;74:2033–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al Khaja KA, Sequeira RP, Alkhaja AK, et al. Drug treatment of hypertension in pregnancy: a critical review of adult guideline recommendations. J Hypertens. 2014;32:454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;32:3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dasgupta K, Quinn RR, Zarnke KB, et al. The 2014 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Luehr DWT, Burke R, Dohmen F, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Hypertension Diagnosis and Treatment. http://www.icsi.org. Updated November 2012. Accessed February 3, 2015.

- 16. Sanchez RA, Ayala M, Baglivo H, et al. Latin American guidelines on hypertension. Latin American Expert Group. J Hypertens. 2009;27:905–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Institute for Health Excellence (NICE) . Hypertension: management of hypertension in adults in primary care. Clinical guideline CG127. 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127. Updated October 2013. Accessed February 3, 2015.

- 18. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res. 2014;37:253–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiang CE, Wang TD, Li YH, et al. 2010 Guidelines of the Taiwan Society of Cardiology for the Management of Hypertension. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109:740–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seedat Y, Rayner B. South African Hypertension Society . South African Hypertension Guideline 2011. S Afr Med J. 2012;102:57–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Heart Foundation of Australia (National Blood Pressure and Vascular Disease Advisory Committee) . Guide to the management of of hypertension 2008. http://www.heartfoundation.org.au. Updated December 2010. Accessed February 3, 2015.

- 23. Saudi Hypertension Management Group and National Commission for Hypretension . Saudi Hypertension Management Guidelines Synopsis 2011. http://www.ssfcm.org/addon/files/hypertension.pdf. Published 2011. Acessed February 3, 2015.

- 24. The Egyptian Hypertension Society . Egyptian Hypertension Guidelines 2014.http://ehs-egypt.net. Published 09 Jan 2015. Accessed February 3, 2015.

- 25. Al‐Ansary LA, Tricco AC, Adi Y, et al. A systematic review of recent clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis, assessment and management of hypertension. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perry HM Jr, Smith WM, McDonald RH, et al. Morbidity and mortality in the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) pilot study. Stroke. 1989;20:4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goto Y, Ishii M, Saruta T, et al. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2115–2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ogihara T, Saruta T, Matsuoka H, et al. Valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension (VALISH) study: rationale and design. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:657–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al. Randmised double‐blind compariosn of palcebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension: the Systolic Hyperension in Europe (Syst‐Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet 1997;350:757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weber M. Recently published hypertension guidelines of the JNC 8 Panelists, the American Society of Hypertension/International Society of Hypertension and Other Major organizations: introductions to a focus issue of the Journal of Clinical Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:241–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly; a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Cpnsensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2037–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blood PLTTC, Turnbull F, Neal B, Ninomiya T, et al. Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta‐analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2008;336:1121–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Staessen J, Fagard R, Amery A. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: implications of Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) for clinical practice and for the ongoing trials. J Hum Hypertens. 1991;5:469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Dahlof B, et al. The Swedish Trial in old patients with hypertension‐2 (STOP‐hypertension‐2): a progress report. Blood Press. 1996;5:300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Messerli FH, Grossman E, Goldbourt U. Are beta‐blockers efficacious as first‐line therapy for hypertension in the elderly? A systematic review. JAMA 1998;279:1903–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khan N, McAlister FA. Re‐examining the efficacy of beta‐blockers for the treatment of hypertension: a meta‐analysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;174:1737–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, et al. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995;273:1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rejnmark L. The ageing endocrine system: fracture risk after initiation of antihypertensive therapy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:189–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sato I, Akazawa M. Polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions in Japanese elderly taking antihypertensives: a retrospective database study. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2013;5:143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schäfer H‐H, De Villiers JN, Sudano I, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of hypertension in the elderly and very elderly–a scotoma within international guidelines. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:W13574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Allen M, Kelly K, Fleming I. Hypertension in elderly patients: recommended systolic targets are not evidence based. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:19–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mutasingwa DR, Ge H, Upshur RE. How applicable are clinical practice guidelines to elderly patients with comorbidities? Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:e253–e262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hypertension: an urgent need for global control and prevention. Lancet. 2014;383:1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]