Statement of Purpose

These guidelines have been written to provide a straightforward approach to managing hypertension in the community. We have intended that this brief curriculum and set of recommendations be useful not only for primary care physicians and medical students, but for all professionals who work as hands‐on practitioners.

We are aware that there is great variability in access to medical care among communities. Even in so‐called wealthy countries there are sizable communities in which economic, logistic, and geographic issues put constraints on medical care. And, at the same time, we are been reminded that even in countries with highly limited resources, medical leaders have assigned the highest priority to supporting their colleagues in confronting the growing toll of devastating strokes, cardiovascular events, and kidney failure caused by hypertension.

Our goal has been to give sufficient information to enable health care practitioners, wherever they are located, to provide professional care for people with hypertension. All the same, we recognize that it will often not be possible to carry out all of our suggestions for clinical evaluation, tests, and therapies. Indeed, there are situations where the most simple and empirical care for hypertension—simply distributing whatever antihypertensive drugs might be available to people with high blood pressure—is better than doing nothing at all. We hope that we have allowed sufficient flexibility in this statement to enable responsible clinicians to devise workable plans for providing the best possible care for patients with hypertension in their communities.

We have divided this brief document into the following sections:

Introduction

Epidemiology

Special Issues With Black Patients (African Ancestry)

How is Hypertension Defined?

How is Hypertension Classified?

Causes of Hypertension

Making the Diagnosis of Hypertension

Evaluating the Patient

Physical Examination

Tests

Goals of Treating Hypertension

Nonpharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension

Drug treatment for Hypertension

Brief Comments on Drug Classes

Treatment‐Resistant Hypertension

Introduction

About one third of adults in most communities in the developed and developing world have hypertension.

Hypertension is the most common chronic condition dealt with by primary care physicians and other health practitioners.

Most patients with hypertension have other risk factors as well, including lipid abnormalities, glucose intolerance, or diabetes; a family history of early cardiovascular events; obesity; and cigarette smoking.

The success of treating hypertension has been limited, and despite well‐established approaches to diagnosis and treatment, in many communities fewer than half of all hypertensive patients have adequately controlled blood pressure.

Epidemiology

There is a close relationship between blood pressure levels and the risk of cardiovascular events, strokes, and kidney disease.

The risk of these outcomes is lowest at a blood pressure of around 115/75 mm Hg

Above 115/75 mm Hg, for each increase of 20 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure or 10 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure, the risk of major cardiovascular and stroke events doubles.

The high prevalence of hypertension in the community is currently being driven by two phenomena: the increased age of our population and the growing prevalence of obesity, which is seen in developing as well as developed countries. In many communities, high dietary salt intake is also a major factor.

The main risk of events is tied to an increased systolic blood pressure; after age 50 or 60 years, diastolic blood pressure may actually start to decrease, but systolic pressure continues to rise throughout life. This increase in systolic blood pressure and decrease in diastolic blood pressure with aging reflects the progressive stiffening of the arterial circulation. The reason for this effect of aging is not well understood, but high systolic blood pressures in older people represent a major risk factor for cardiovascular and stroke events and kidney disease progression.

Special Issues With Black Patients (African Ancestry)

Hypertension is a particularly common finding in black people.

Hypertension occurs at a younger age and is often more severe in terms of blood pressure levels in black patients than in whites.

A higher proportion of black people are sensitive to the blood pressure–raising effects of salt in the diet than white patients, and this—together with obesity, especially among women—may be part of the explanation for why young black people tend to have earlier and more severe hypertension than other groups.

Black patients with hypertension are particularly vulnerable to strokes and hypertensive kidney disease. They are 3 to 5 times as likely as whites to have renal complications and end‐stage kidney disease.

There is a tendency for black patients to have differing blood pressure responses to the available antihypertensive drug classes: they usually respond well to treatment with calcium channel blockers and diuretics but have smaller blood pressure reductions with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and β‐blockers. However, appropriate combination therapies provide powerful antihypertensive responses that are similar in black and white patients. Most patients will require more than one antihypertensive drug to maintain blood pressure control.

How is Hypertension Defined?

Most major guidelines recommend that hypertension be diagnosed when a person's systolic blood pressure is ≥140 mm Hg or their diastolic blood pressure is ≥90 mmHg, or both, on repeated examination. The systolic blood pressure is particularly important and is the basis for diagnosis in most patients.

These numbers apply to all adults older than 18 years, although for patients aged 80 or older a systolic blood pressure up to 150 mm Hg is now regarded as acceptable.

The goal of treating hypertension is to reduce blood pressure to levels below the numbers used for making the diagnosis.

These definitions are based on the results of major clinical trials that have shown the benefits of treating people to these levels of blood pressure. Even though a blood pressure of 115/75 mm Hg is ideal, as discussed earlier, there is no evidence to justify treating hypertension down to such a low level.

We do not have sufficient information about younger adults (between 18 and 55 years) to know whether they might benefit from defining hypertension at a level <140/90 mmHg (eg, 130/80 mm Hg) and treating them more aggressively than older adults. Thus, guidelines tend to use 140/90 mm Hg for all adults (up to 80 years). Even so, at a practitioner's discretion, lower blood pressure targets may be considered in young adults, provided the therapy is well tolerated.

Some recent guidelines have recommended diagnostic values of 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. However, the clinical benefits of this lower target have not been established and so these patients should be treated to <140/90 mm Hg.

How is Hypertension Classified?

For patients with systolic blood pressure between 120 mm Hg and 139 mm Hg, or diastolic pressures between 80 and 89 mm Hg, the term prehypertension can be used. Patients with this condition should not be treated with blood pressure medications; however, they should be encouraged to make lifestyle changes in the hope of delaying or even preventing progression to hypertension.

Stage 1 hypertension: patients with systolic blood pressure 140 to 159 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure 90 to 99 mm Hg.

Stage 2 hypertension: systolic blood pressure ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥100 mm Hg.

Causes of Hypertension

Primary Hypertension

About 95% of adults with high blood pressure have primary hypertension (sometimes called essential hypertension).

The cause of primary hypertension is not known, although genetic and environmental factors that affect blood pressure regulation are now being studied.

Environmental factors include excess intake of salt, obesity, and perhaps sedentary lifestyle.

Some genetically related factors could include inappropriately high activity of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system and the sympathetic nervous system and susceptibility to the effects of dietary salt on blood pressure.

Another common cause of hypertension is stiffening of the aorta with increasing age. This causes hypertension referred to as isolated or predominant systolic hypertension characterized by high systolic pressures (often with normal diastolic pressures), which are found primarily in elderly people.

Secondary Hypertension

This pertains to the relatively small number of cases, about 5% of all hypertension, where the cause of the high blood pressure can be identified and sometimes treated.

The main types of secondary hypertension are chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenosis, excessive aldosterone secretion, pheochromocytoma, and sleep apnea.

A simple screening approach for identifying secondary hypertension is given later.

Making the Diagnosis of Hypertension

Blood pressure can be measured by either a conventional sphygmomanometer using a stethoscope or by an automated electronic device. The electronic device, if available, is preferred because it provides more reproducible results than the older method and is not influenced by variations in technique or by the bias of the observers. If the auscultatory method is used, the first and fifth Korotkoff sounds (the appearance and disappearance of sounds) will correspond to the systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

Arm cuffs are preferred. Cuffs that fit on the finger or wrist are often inaccurate and should, in general, not be used.

It is important to ensure that the correct size of the arm cuff is used (in particular, a wider cuff in patients with large arms [>32 cm circumference]).

At the initial evaluation, blood pressure should be measured in both arms; if the readings are different, the arm with the higher reading should be used for measurements thereafter.

The blood pressure should be taken after patients have emptied their bladders. Patients should be seated with their backs supported and with their legs resting on the ground and in the uncrossed position for 5 minutes.

The patient's arm being used for the measurement should be at the same level as the heart, with the arm resting comfortably on a table.

It is preferable to take 2 readings, 1 to 2 minutes apart, and use the average of these measurements.

It is useful to also obtain standing blood pressures (usually after 1 minute and again after 3 minutes) to check for postural effects, particularly in older people.

In general, the diagnosis of hypertension should be confirmed at an additional patient visit, usually 1 to 4 weeks after the first measurement. On both occasions, the systolic blood pressure should be ≥140 mm Hg or the diastolic pressure ≥90 mmHg, or both, in order to make a diagnosis of hypertension.

If the blood pressure is very high (for instance, a systolic blood pressure ≥180 mm Hg), or if available resources are not adequate to permit a convenient second visit, the diagnosis and, if appropriate, treatment can be started after the first set of readings that demonstrate hypertension.

For practitioners and their staff not experienced in measuring blood pressures, it is necessary to receive appropriate training in performing this important technique.

Some patients may have blood pressures that are high in the clinic or office but are normal elsewhere. This is often called white‐coat hypertension. If it is suspected, consider getting home blood pressure readings (see below) to check this possibility. Another approach is to use ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, if it is available. In this procedure, the patient wears an arm cuff connected to a device that automatically measures and records blood pressures at regular intervals usually over a 24‐hour period.

It can be helpful to measure blood pressures at home. If available, the electronic device is simpler to use and is probably more reliable than the sphygmomanometer. The average of blood pressures measured over 5 to 7 days, if possible in duplicate at each measurement, can be a useful guide for diagnostic and treatment decisions.

Evaluating the Patient

Often, high blood pressure is only one of several cardiovascular risk factors that require attention.

Before starting treatment for hypertension, it is useful to evaluate the patient more thoroughly. The three methods are personal history, physical examination. and selective testing.

History

Ask about previous cardiovascular events because they often suggest an increased probability of future events that can influence the choice of drugs for treating hypertension and will also require more aggressive treatment of all cardiovascular risk factors. Also ask patients if they have previously been told that they have hypertension and, if relevant, their responses to any drugs they might have been given.

Important previous events include

Stroke or transient ischemic attacks or dementia. Why is this information important? For patients with these previous events, it may be necessary to include particular drug types in their treatment, for instance angiotensin receptor blockers or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics, as well as drugs for low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (statins) and antiplatelet drugs.

Coronary artery disease, including myocardial infarctions, angina pectoris, and coronary revascularizations. Why is this important? Certain medications would be preferred, for instance β‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, and antiplatelet agents (aspirin).

Heart failure or symptoms suggesting left ventricular dysfunction (shortness of breath, edema). Why is this important? Certain medications would be preferred in such patients, including angiotensin receptor blockers or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, β‐blockers, diuretics, and spironolactone. Also, certain medications should be avoided, such as nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil, diltiazem), in patients with systolic heart failure.

Chronic kidney disease. Why is this important? Certain medications would be preferred, including angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (although these two drug classes should not be prescribed in combination with each other), statins, and diuretics (loop diuretics may be required if the estimated glomerular filtration rate is below 30) and blood pressure treatment targets might be lower (130/80 mm Hg) if albuminuria is present. Note: In patients with more advanced kidney disease, the use of some of these drugs often requires the expertise of a nephrologist.

Peripheral artery disease. Why is this important? This finding suggests advanced arterial disease that may also exist in the coronary or brain circulations, even in the absence of clinical history. It is vital that smoking be discontinued. In most cases, antiplatelet drugs should be used.

Diabetes. Why is this important? This condition is commonly associated with hypertension and an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Certain medications such as angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors should be used, particularly if there is evidence of albuminuria or chronic kidney disease. Good blood pressure control, often requiring the addition of calcium channel blockers and diuretics, is also important in these patients.

Sleep apnea. Why is this important? Special treatments are often required for these patients and their use may make it possible to improve blood pressure control as well as other findings of this condition.

Ask about other risk factors. Why is this important? Risk factors can affect blood pressure targets and treatment selection for the hypertension. Thus, knowing about age, dyslipidemia, microalbuminuria, gout, or family history of hypertension and diabetes can be valuable. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor that must be identified so that counseling can be given about stopping this dangerous habit.

Ask about concurrent drugs. Commonly used drugs (for indications unrelated to treating hypertension) can increase blood pressure and therefore should be stopped if possible. These include nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs used for arthritis and pain relief, some tricyclic and other types of antidepressants, older high‐dose oral contraceptives, migraine medications, and cold remedies (eg, pseudoephedrine). In addition, some patients may be taking herbal medications, folk remedies, or recreational drugs (eg, cocaine), which can increase blood pressure.

Physical Examination

At the first visit it is important to perform a complete physical examination because often getting care for hypertension is the only contact that patients have with a medical practitioner.

Measuring blood pressure (discussed earlier).

Document the patient's weight and height and calculate body mass index. This can be done by going online to Google, searching BMI, and entering the patient's weight and height as instructed (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/BMI/bmicalc.htm) Why is this important? This helps to set targets for weight loss and, as discussed later, knowing whether a patient is obese or not obese might affect the choice of hypertension treatment. It should be noted that the risk of cardiovascular events, including stroke, paradoxically may be higher in lean hypertensive patients than in obese patients.

Waist circumference. Why is this important? Independent of weight, this helps determine whether a patient has the metabolic syndrome or is at risk for type 2 diabetes. Risk is high when the measurement is >102 cm in men or >88 cm in women.

Signs of heart failure. Why is this important? This diagnosis strongly influences the choice of hypertension therapy. Left ventricular hypertrophy can be suspected by chest palpation, and heart failure can be indicated by distended jugular veins, rales on chest examination, an enlarged liver, and peripheral edema.

Neurologic examination. Why is this important? This may reveal signs of previous stroke and affect treatment selection.

Eyes: If possible, the optic fundi should be checked for hypertensive or diabetic changes and the areas around the eyes for findings such as xanthomas.

Pulse: It is important to check peripheral pulse rates; if they are diminished or absent, this can indicate peripheral artery disease.

Tests

Blood sample

Note: This preferably should be a fasting sample so that a fasting blood glucose level and more accurate lipid profiles can be obtained.

Electrolytes. Why is this important? There is a special emphasis on potassium: high levels can suggest renal disease, particularly if creatinine is elevated. Low values can suggest aldosterone excess. In addition, illnesses associated with severe diarrhea are common in some communities and can cause hypokalemia and other electrolyte changes.

Fasting glucose concentration. Why is this important? If elevated, this could be indicative of impaired glucose tolerance, or, if sufficiently high, of diabetes. If available, glycated hemoglobin should be measured to further assess an elevated glucose level and help in making a diagnosis.

Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen. Why are these important? Increased creatinine levels are usually indicative of kidney disease; creatinine is also used in formulae for eGFR. When appropriate, use formulae designed for eGFR calculations in patients of African ancestry.

Lipids. Why are these important? Elevated LDL cholesterol or low values of high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol are associated with increased cardiovascular risk. High LDL cholesterol can typically be treated with available drugs, usually statins.

Hemoglobin/hematocrit. Why are these important? These measurements can identify issues beyond hypertension and cardiovascular disease, including sickle cell anemia in vulnerable populations and anemia associated with chronic kidney disease.

Liver function tests. Why are these important? Certain blood pressure drugs can affect liver function, so it is useful to have baseline values. Also, obese people can have fatty liver disorders that should be identified and considered in overall management.

Urine sample

-

○

Albuminuria. Why is this important? If present, this can be indicative of kidney disease and is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Ideally, an albumin/creatinine ratio should be obtained, but even dipstick evidence of albuminuria (+1 or greater) is helpful.

-

○

Red and white cells. Why are these important? Positive findings can be indicative of urinary tract infections, kidney stones, or other potentially serious urinary tract conditions, including bladder tumors.

Electrocardiography. Why is this important? Electrocardiography (ECG) can help identify previous myocardial infarctions or left atrial and ventricular hypertrophy (which is evidence of target organ damage and indicative of the need for good control of blood pressure). ECG might also identify cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation (which would dictate the use of certain drugs) or conditions such as heart block (which would contraindicate certain drugs, eg, β‐blockers, rate‐slowing calcium channel blockers). Echocardiography, if available, can also be helpful in diagnosing left ventricular hypertrophy and quantifying the ejection fraction in patients with suspected heart failure, although this test is not routine in hypertensive patients.

Overall Goals of Treatment

The goal of treatment is to manage hypertension and to deal with all the other identified risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including lipid disorders, glucose intolerance or diabetes, obesity, and smoking.

For hypertension, the treatment goal for systolic blood pressure is usually <140 mm Hg and for diastolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg. In the past, guidelines have recommended treatment values of <130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and coronary artery disease. However, evidence to support this lower target in patients with these conditions is lacking, so the goal of <140/90 mm Hg should generally be used, although some experts still recommend <130/80 mm Hg if albuminuria is present in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Are there other exceptions to <140/90 mm Hg? Most evidence linking the effects on cardiovascular or renal outcomes to treated blood pressures have been based on clinical trials in middle‐aged to elderly patients (typically between 55 and 80 years). Some recent trials suggest that in people 80 or older, achieving a systolic blood pressure of <150 mm Hg is associated with strong cardiovascular and stroke protection and so a target of <150/90 mm Hg is now recommended for patients in this age group. We have almost no clinical trial evidence regarding blood pressure targets in patients younger than 50 years. Diastolic blood pressure may be important in this age group, so achieving a value <90 mm Hg should be a priority. In addition, it is also a reasonable expectation that targets <140/90 mm Hg (eg, < 130/80 mm Hg) could be appropriate in young adults and can be considered.

It is important to inform patients that the treatment of hypertension is usually expected to be a life‐long commitment and that it can be dangerous for them to terminate their treatment with drugs or lifestyle changes without first consulting their practitioner.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Several lifestyle interventions have been shown to reduce blood pressure. Apart from contributing to the treatment of hypertension, these strategies are beneficial in managing most of the other cardiovascular risk factors. In patients with hypertension that is no more severe than stage 1 and is not associated with evidence of abnormal cardiovascular findings or other cardiovascular risks, 6 to 12 months of lifestyle changes can be attempted in the hope that they may be sufficiently effective to make it unnecessary to use medicines. However, it may be prudent to start treatment with drugs sooner if it is clear that the blood pressure is not responding to the lifestyle methods or if other risk factors appear. Also, in practice settings where patients have logistical difficulties in making regular clinic visits, it might be most practical to start drug therapy early. In general, lifestyle changes should be regarded as a complement to drug therapy rather than an alternative.

Weight loss: In patients who are overweight or obese, weight loss is helpful in treating hypertension, diabetes, and lipid disorders. Substituting fresh fruits and vegetables for more traditional diets may have benefits beyond weight loss. Unfortunately, these diets can be relatively expensive and inconvenient for patients, and can work only if patients are provided with a strong support system. Even modest weight loss can be helpful.

Salt reduction: High‐salt diets are common in many communities. Reduction of salt intake is recommended because it can reduce blood pressure and decrease the need for medications in patients who are “salt sensitive,” which may be a fairly common finding in black communities. Often, patients are unaware that there is a large amount of salt in foods such as bread, canned goods, fast foods, pickles, soups, and processed meats. This intake can be difficult to change because salty foods are often part of the traditional diets found in many cultures. A related problem is that many people eat diets that are low in potassium, and they should be taught about available sources of dietary potassium.

Exercise: Regular aerobic exercise can help reduce blood pressure, but opportunities to follow a structured exercise regimen are often limited. Still, patients should be encouraged to walk, use bicycles, climb stairs, and pursue means of integrating physical activity into their daily routines.

Alcohol consumption: Up to 2 drinks a day can be helpful in protecting against cardiovascular events, but greater amounts of alcohol can raise blood pressure and should therefore be discouraged. In women, alcohol should be limited to 1 drink a day.

Cigarette smoking: Stopping smoking will not reduce blood pressure, but since smoking by itself is such a major cardiovascular risk factor, patients must be strongly urged to discontinue this habit. Patients should be warned that stopping smoking may be associated with a modest increase in body weight.

Drug Treatment of Hypertension

-

I

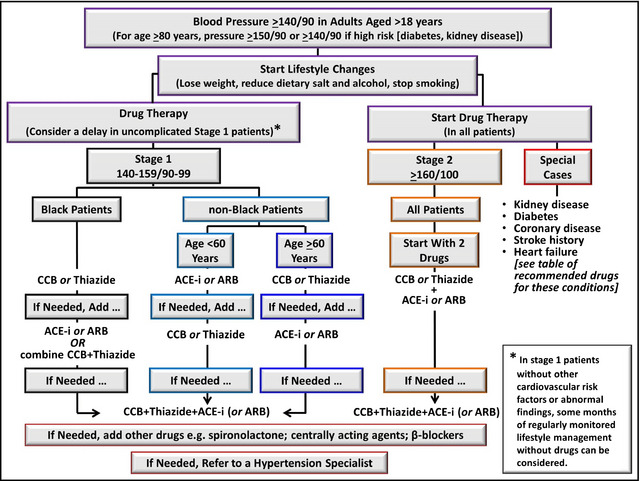

Starting treatment: (see the algorithm in the Figure). Treatment with drugs should be started in patients with blood pressures >140/90 mm Hg in whom lifestyle treatments have not been effective. (Note: As discussed earlier in Section 12 on Nonpharmacologic Treatment, drug treatment can be delayed for some months in patients with stage 1 hypertension who do not have evidence of abnormal cardiovascular findings or other risk factors. In settings where healthcare resources are highly limited, clinicians can consider extending the nondrug observation period in uncomplicated stage 1 hypertensive patients provided there is no evidence for an increase in blood pressure or the appearance of cardiovascular or renal findings).

In patients with stage 2 hypertension (blood pressure ≥160/100 mm Hg), drug treatment should be started immediately after diagnosis, usually with a 2‐drug combination, without waiting to see the effects of lifestyle changes. Drug treatment can also be started immediately in all hypertensive patients in whom, for logistical or other practical reasons, the practitioner believes it is necessary to achieve more rapid control of blood pressure. The presence of other cardiovascular risk factors should also accelerate the start of hypertension treatment.

-

II

For patients older than 80 years, the suggested threshold for starting treatment is at levels ≥150/90 mm Hg. Thus, the target of treatment should be <140/90 mm Hg for most patients but <150/90 mm Hg for older patients (unless these patients have chronic kidney disease or diabetes, when <140/90 mm Hg can be considered).

-

III

The treatment regimen:

Most patients will require more than one drug to achieve control of their blood pressure.

In general, increase the dose of drugs or add new drugs at approximately 2‐ to 3‐week intervals. This frequency can be faster or slower depending on the judgment of the practitioner. In general, the initial doses of drugs chosen should be at least half of the maximum dose so that only one dose adjustment is required thereafter. It is generally anticipated that most patients should reach an effective treatment regimen, whether 1, 2, or 3 drugs, within 6 to 8 weeks.

If the untreated blood pressure is at least 20/10 mm Hg above the target blood pressure, consider starting treatment immediately with 2 drugs.

-

IV

Choice of drugs:

This should be influenced by the age, ethnicity/race, and other clinical characteristics of the patient (Table 1).

The choice of drugs will also be influenced by other conditions (eg, diabetes and coronary disease) associated with the hypertension (Table 2). Pregnancy also influences drug choice.

Long‐acting drugs that need to be taken only once daily are preferred to shorter‐acting drugs that require multiple doses because patients are more likely to follow a simple treatment regimen. For the same reason, when more than one drug is prescribed, the use of a combination product with two appropriate medications in a single tablet can simplify treatment for patients, although these products can sometimes be more expensive than individual drugs. Once‐daily drugs can be taken at any time during the day, most usually either in the morning or in the evening before sleep. If multiple drugs are needed, it is possible to divide them between the morning and the evening.

The choice of drugs will further be influenced by their availability and affordability. In many cases, it is necessary to use whichever drugs have been provided by government or other agencies. For this reason, we will only make recommendations for drug classes, not individual agents, recognizing that there may be a limited selection of drugs that can be prescribed by a practitioner. Even among generic drugs there can be a wide variation in cost.

Recommendations for drug selection are shown in Table 1 (Part 1) for patients whose primary problem is hypertension, and in Table 1 (Part 2) for patients who have a major comorbidity associated with their hypertension. The Figure 1 displays an algorithm that summarizes the use of therapy for most patients with hypertension. The recommendations for particular drug classes are made with the recognition that sometimes only alternative drug classes will be available. However, most of the time, the use of any drugs that reduce blood pressure is more likely to help protect patients from strokes and other serious events than giving patients no drug at all.

Table 1.

Drug Selection in Hypertensive Patients With or Without Other Major Conditions

| Patient Type | First Drug | Add Second Drug If Needed to Achieve a BP <140/90 mm Hg | If Third Drug is Needed to Achieve a BP of <140/90 mm Hg |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. When hypertension is the only or main condition | |||

| Black patients (African ancestry): All ages | CCBa or thiazide diuretic | ARBb or ACE inhibitor (If unavailable can add alternative first drug choice) | Combination of CCB + ACE inhibitor or ARB + thiazide diuretic |

| White and other non‐black Patients: Younger than 60 | ARBb or ACE inhibitor | CCBa or thiazide diuretic | Combination of CCB + ACE inhibitor or ARB + thiazide diuretic |

| White and other non‐black patients: 60 y and older | CCBa or thiazide diuretic (Although ACE inhibitors or ARBs are also usually effective) | ARBb or ACE inhibitor (or CCB or thiazide if ACE inhibitor or ARB used first) | Combination of CCB + ACE inhibitor or ARB + thiazide diuretic |

| B. When hypertension is associated with other conditions | |||

| Hypertension and diabetes | ARB or ACE inhibitor Note: in black patients, it is acceptable to start with a CCB or thiazide | CCB or thiazide diuretic Note: in black patients, if starting with a CCB or thiazide, add an ARB or ACE inhibitor | The alternative second drug (thiazide or CCB) |

| Hypertension and chronic kidney disease | ARB or ACE inhibitor Note: in black patients, good evidence for renal protective effects of ACE inhibitors | CCB or thiazide diureticc | The alternative second drug (thiazide or CCB) |

| Hypertension and clinical coronary artery diseased | β‐Blocker plus ARB or ACE inhibitor | CCB or thiazide diuretic | The alternative second step drug (thiazide or CCB) |

| Hypertension and stroke historye | ACE inhibitor or ARB | Thiazide diuretic or CCB | The alternative second drug (CCB or thiazide) |

| Hypertension and heart failure | Patients with symptomatic heart failure should usually receive an ARB or ACE inhibitor + β‐blocker + diuretic + spironolactone regardless of blood pressure. A dihydropyridine CCB can be added if needed for BP control. | ||

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

CCBs are generally preferred, but thiazides may cost less.

ARBs can be considered because ACE inhibitors can cause cough and angioedema, although ACE inhibitors may cost less.

If eGFR <40 mL/min, a loop diuretic (eg, furosemide or torsemide) may be needed.

Note: If history of myocardial infarction, a β‐blocker and ARB/or ACE inhibitor are indicated regardless of blood pressure.

Note: If using a diuretic, there is good evidence for indapamide (if available).

Table 2.

Dosages of Commonly Used Antihypertensive Drugs

| Daily Dosage, mg | ||

|---|---|---|

| Low Dosage | Usual Dosage | |

| Calcium channel blockers | ||

| Nondihydropyridines | ||

| Diltiazem | 120 | 240–360 |

| Verapamil | 120 | 240–480 |

| Dihydropyridines | ||

| Amlodipine | 2.5 | 5–10 |

| Felodipine | 2.5 | 5–10 |

| Isradipine | 2.5 twice daily | 5–10 twice daily |

| Nifedipine | 30 | 30–90 |

| Nitrendipine | 10 | 20 |

| Drugs that target the renin‐angiotensin system | ||

| Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors | ||

| Benazepril | 5 | 10–40 |

| Captopril | 12.5 twice daily | 50–100 twice daily |

| Enalapril | 5 | 10–40 |

| Fosinopril | 10 | 10–40 |

| Lisinopril | 5 | 10–40 |

| Perindopril | 4 | 4–8 |

| Quinapril | 5 | 10–40 |

| Ramipril | 2.5 | 5–10 |

| Trandolapril | 1–2 | 2–8 |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | ||

| Azilsartan | 40 | 80 |

| Candesartan | 4 | 8–32 |

| Eprosartan | 400 | 600–800 |

| Irbesartan | 150 | 150–300 |

| Losartan | 50 | 50–100 |

| Olmesartan | 10 | 20–40 |

| Telmisartan | 40 | 40–80 |

| Valsartan | 80 | 80–320 |

| Direct renin inhibitor | ||

| Aliskiren | 75 | 150–300 |

| Diuretics | ||

| Thiazide and thiazide‐like diuretics | ||

| Bendroflumethiazide | 5 | 10 |

| Chlorthalidone | 12.5 | 12.5–25 |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 12.5 | 12.5–50 |

| Indapamide | 1.25 | 2.5 |

| Loop diuretics | ||

| Bumetanide | 0.5 | 1 |

| Furosemide | 20 twice daily | 40 twice daily |

| Torsemide | 5 | 10 |

| Potassium‐sparing diuretics | ||

| Amiloride | 5 | 5–10 |

| Eplerenone | 25 | 50–100 |

| Spironolactone | 12.5 | 25–50 |

| Triamterene | 100 | 100 |

| β‐Blockers | ||

| Acebutalol | 200 | 200–400 |

| Atenolol | 25 | 100 |

| Bisoprolol | 5 | 5–10 |

| Carvedilol | 3.125 twice daily | 6.25–25 twice daily |

| Labetalol | 100 twice daily | 100–300 twice daily |

| Metoprolol succinate | 25 | 50–100 |

| Metoprolol tartrate | 25 twice daily | 50–100 twice daily |

| Nadolol | 20 | 40–80 |

| Nebivolol | 2.5 | 5–10 |

| Propranolol | 40 twice daily | 40–160 twice daily |

| α‐Adrenergic receptor blockers | ||

| Doxazosin | 1 | 1–2 |

| Prazosin | 1 twice daily | 1–5 twice daily |

| Terazosin | 1 | 1–2 |

| Vasodilators, central α‐agonists, and adrenergic depleters | ||

| Vasodilators | ||

| Hydralazine | 10 twice daily | 25–100 twice daily |

| Minoxidil | 2.5 | 5–10 |

| Central alpha‐agonists | ||

| Clonidine | 0.1 twice daily | 0.1–0.2 twice daily |

| Clonidine patch | TTS‐1, once weekly | TTS‐1, 2, or 3, once weekly |

| Methyldopa | 125 twice daily | 250–500 twice daily |

| Adrenergic depleters | ||

| Reserpine | 0.1 | 0.1–0.25 |

All doses are given once‐daily unless otherwise specified.

Figure 1.

This algorithm summarizes the main recommendations of these guidelines. At any stage it is entirely appropriate to seek help from a hypertension expert if treatment is proving difficult. In patients with stage 1 hypertension in whom there is no history of cardiovascular, stroke, or renal events or evidence of abnormal findings and who do not have diabetes or other major risk factors, drug therapy can be delayed for some months. In all other patients (including those with stage 2 hypertension), it is recommended that drug therapy be started when the diagnosis of hypertension is made. CCB indicates calcium channel blocker; ACE‐i, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; thiazide, thiazide or thiazide‐like diuretics. Blood pressure values are in mm Hg.

Brief Comments on Drug Classes

Note: There is an assumption, unless otherwise stated, that all drugs in a class are similar to each other. We only mention individual agents if they have an important property that is not shared by the others in its class. Table 2 provides a list of commonly used antihypertensive drugs and their doses.

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme Inhibitors

These agents reduce blood pressure by blocking the renin‐angiotensin system. They do this by preventing conversion of angiotensin I to the blood pressure‐raising hormone angiotensin II. They also increase availability of the vasodilator bradykinin by blocking its breakdown.

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors are well tolerated. Their main side effect is cough (most common in women and in patients of Asian and African background). Angioedema is an uncommon but potentially serious complication that can threaten airway function, and it occurs most frequently in black patients.

These drugs can increase serum creatinine by as much as 30%, but this is usually because they reduce pressure within the renal glomerulus and decrease filtration. This is a reversible change in function and is not harmful. An even greater increase in creatinine sometimes occurs when angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors are combined with diuretics and produce large blood pressure reductions. Again, this change is reversible, although it may be necessary to reduce doses of one or both drugs. If creatinine levels increase substantially this can be caused by concomitant treatment with nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs or it may indicate the presence of renal artery stenosis.

The side effects associated with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors are generally not dose‐dependent, as they occur as frequently at low doses as at high doses. Thus, it can be perfectly acceptable when using these agents to start at medium or even high doses. The one exception to this rule is in hyperkalemia, which may occur more frequently at higher angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor doses.

These drugs have established clinical outcome benefits in patients with heart failure, post–myocardial infarction, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and diabetic and nondiabetic chronic kidney disease.

In general, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors are more effective as monotherapy in reducing blood pressure in white patients than in black patients, possibly because the renin‐angiotensin system is often less active in black patients. However, these drugs are equally effective in reducing blood pressure in all ethnic and racial groups when combined with either calcium channel blockers or diuretics.

Do not combine angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors with angiotensin receptor blockers; each of these drug types is beneficial in patients with kidney disease, but in combination they may actually have adverse effects on kidney function.

When starting treatment with an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, there is a risk of hypotension in patients who are already taking diuretics or are on very low‐salt diets or are dehydrated (eg, laborers in hot climates and patients with diarrhea). For patients taking a diuretic, skipping a dose before starting the angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor helps prevent this sudden effect on blood pressure.

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors must not be used in pregnancy, especially in the second or third trimesters, since they can compromise the normal development of the fetus.

Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

Angiotensin receptor blockers, like angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, antagonize the renin‐angiotensin system. They reduce blood pressure by blocking the action of angiotensin II on its AT1 receptor and thus prevent the vasoconstrictor effects of this receptor.

The angiotensin receptor blockers are well tolerated. Because they do not cause cough and only rarely cause angioedema, and have effects and benefits similar to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, they are generally preferred over angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors if they are available and affordable. Like angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers can increase serum creatinine (see comments about angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors), but usually this is a functional change that is reversible and not harmful.

These drugs do not appear to have dose‐dependent side effects, so it is perfectly reasonable to start treatment with medium or even maximum approved doses.

These drugs have the same benefits on cardiovascular and renal outcomes as angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors.

Like angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, they tend to work better in white and Asian patients than in black patients, but, when combined with either calcium channel blockers or diuretics, they become equally effective in all patient groups.

Do not combine angiotensin receptor blockers with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; each of these drug types is beneficial in patients with kidney disease, but in combination they may actually have adverse effects on renal events.

When starting treatment with an angiotensin receptor blocker in patients already taking diuretics, it may be beneficial to skip a dose of the diuretic to prevent a sudden fall in blood pressure.

Angiotensin receptor blockers must not be used in pregnancy, especially in the second or third trimesters, since they can compromise the normal development of the fetus.

Thiazide and Thiazide‐like Diuretics

These agents work by increasing excretion of sodium by the kidneys and additionally may have some vasodilator effects.

Clinical outcome benefits (reduction of strokes and major cardiovascular events) have been best established with chlorthalidone, indapamide, and hydrochlorothiazide, although evidence for the first two of these agents has been the strongest.

Chlorthalidone has more powerful effects on blood pressure than hydrochlorothiazide (when the same doses are compared) and has a longer duration of action.

The main side effects of these drugs are metabolic (hypokalemia, hyperglycemia, and hyperuricemia). The likelihood of these problems can be reduced by using low doses (eg, 12.5 mg or 25 mg of hydrochlorothiazide or chlorthalidone) or by combining these diuretics with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, which have been shown to reduce these metabolic changes. Combining diuretics with potassium‐sparing agents also helps prevent hypokalemia.

Diuretics are most effective in reducing blood pressure when combined with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, although they are also effective when combined with calcium channel blockers.

Note: Thiazides plus β‐blockers are also an effective combination for reducing blood pressure, but since both classes can increase blood glucose concentrations this combination should be used with caution in patients at risk for developing diabetes.

Calcium Channel Blockers

These agents reduce blood pressure by blocking the inward flow of calcium ions through the L channels of arterial smooth muscle cells.

There are two main types of calcium channel blockers: dihydropyridines, such as amlodipine and nifedipine, which work by dilating arteries; and nondihydropyridines, such as diltiazem and verapamil, which dilate arteries somewhat less but also reduce heart rate and contractility.

Most experience with these agents has been with the dihydropyridines, such as amlodipine and nifedipine, which have been shown to have beneficial effects on cardiovascular and stroke outcomes in hypertension trials.

The main side effect of calcium channel blockers is peripheral edema, which is most prominent at high doses; this finding can often be attenuated by combining these agents with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers.

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are not recommended in patients with heart failure, but amlodipine appears to be safe when given to heart failure patients receiving standard therapy (including angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors) for this condition.

Because the nondihydropyridine drugs, verapamil and diltiazem, can slow heart rate, they are sometimes preferred in patients with fast heart rates and even for rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation who cannot tolerate β‐blockers. Nondihydropyridine drugs can also reduce proteinuria.

Calcium channel blockers have powerful blood pressure‐reducing effects, particularly when combined with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. They are equally effective in all racial and ethnic groups.

The dihydropyridine, but not the nondihydropyridine, agents can be safely combined with β‐blockers.

β‐Blockers

β‐blockers reduce cardiac output and also decrease the release of renin from the kidney.

They have strong clinical outcome benefits in patients with histories of myocardial infarction and heart failure and are effective in the management of angina pectoris.

They are less effective in reducing blood pressure in black patients than in patients of other ethnicities.

β‐blockers may not be as effective as the other major drug classes in preventing stroke or cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients, but they are the drugs of choice in patients with histories of myocardial infarction or heart failure.

Many of these agents have adverse effects on glucose metabolism and therefore are not recommended in patients at risk for diabetes, especially in combination with diuretics. They may also be associated with heart block in susceptible patients.

The main side effects associated with β‐blockers are reduced sexual function, fatigue, and reduced exercise tolerance.

The combined α‐ and β‐blocker, labetalol, is widely used intravenously for hypertensive emergencies, and is also used orally for treating hypertension in pregnant and breastfeeding women.

α‐Blockers

α‐Blockers reduce blood pressure by blocking arterial α‐adrenergic receptors and thus preventing the vasoconstrictor actions of these receptors.

These drugs are less widely used as first‐step agents than other classes because clinical outcome benefits have not been as well established as with other agents. However, they can be useful in treating resistant hypertension when used in combination with agents such as diuretics, β‐blockers, and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors.

To be maximally effective, they should usually be combined with a diuretic. Since α‐blockers can have somewhat beneficial effects on blood glucose and lipid levels, they can potentially neutralize some of the adverse metabolic effects of diuretics.

The α‐blockers are effective in treating benign prostatic hypertrophy, and so can be a valuable part of hypertension treatment regimens in older men who have this condition.

Centrally Acting Agents

These drugs, the most well‐known of which are clonidine and α‐methyldopa, work primarily by reducing sympathetic outflow from the central nervous system.

They are effective in reducing blood pressure in most patient groups.

Bothersome side effects such as drowsiness and dry mouth have reduced their popularity. Treatment with a clonidine skin patch causes fewer side effects than the oral agent, but the patch is not always available and can be more costly than the tablets.

In certain countries, including the United States, α‐methyldopa is widely employed for treating hypertension in pregnancy.

Direct Vasodilators

Because these agents, specifically hydralazine and minoxidil, often cause fluid retention and tachycardia, they are most effective in reducing blood pressure when combined with diuretics and β‐blockers or sympatholytic agents. For this reason, they are now usually used only as fourth‐line or later additions to treatment regimens.

Hydralazine is the more widely used of these agents. The powerful drug minoxidil is sometimes used by specialists in patients whose blood pressures are difficult to control. Fluid retention and tachycardia are frequent problems with minoxidil, as well as unwanted hair growth (particularly in women). Furosemide is often required to cope with the fluid retention.

Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists

The best known of these agents is spironolactone. Although it was originally developed for the treatment of high aldosterone states, it recently has become part of standard treatment for heart failure. Eplerenone is a newer and better‐tolerated agent, although most experience in difficult‐to‐control hypertension has been with spironolactone.

In addition, these agents can be effective in reducing blood pressure when added to standard 3‐drug regimens (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker/ calcium channel blocker/diuretic) in treatment‐resistant patients. This may be because aldosterone excess can contribute to resistant hypertension.

Symptomatic side effects of gynecomastia (swelling and tenderness of breasts in both men and women) and sexual dysfunction are common. These can be minimized by using spironolactone in a low dose (no more than 25 mg daily) or by using the more selective (but more expensive) agent, eplerenone. Hyperkalemia can also become a problem with these agents, particularly when added to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with reduced renal function. These agents should be used with caution when the eGFR is <50. In particular, when mineralocorticoid receptor blockers are combined with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, potassium levels must be monitored within the first month of treatment and then on a regular basis (every 3–6 months).

Treatment Resistant Hypertension

Hypertension can be controlled (blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg in most patients) by using either 1, 2, or 3 drugs as described earlier (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker/ calcium channel blocker/diuretic) in full or maximally tolerated doses. The most widely used two‐drug combination, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors plus either calcium channel blockers or diuretics, or angiotensin receptor blockers plus either calcium channel blockers or diuretics, can control blood pressure in about 80% of patients.

Confirm that the blood pressure is truly uncontrolled by checking home pressures, or if available, by using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

For patients not controlled on 3 drugs, adding a mineralocorticoid antagonist such as spironolactone, a β‐blocker, a centrally acting agent, an α‐blocker, or a direct vasodilator will often be helpful.

If blood pressure is still not controlled it is important to make certain that patients are actually taking their medicines. Question their families, check their prescriptions, and ask questions about side effects to help confirm compliance with treatment.

Check whether patients are taking other medicines that can interfere with their hypertension treatment. For example: nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, cold remedies, and some antidepressants. Also, ask about diet: blood pressures in some patients are especially sensitive to factors such as excessive salt intake.

Consider secondary causes of hypertension if all these more simple approaches are unsuccessful.

-

○

Secondary hypertension can be suggested by the sudden onset of hypertension, or by the loss of blood pressure control in patients previously well managed or by the occurrence of a hypertension emergency

-

○

Chronic kidney disease: this common secondary cause of hypertension should normally be revealed by the initial patient evaluation (eg, laboratory tests of creatinine). These patients, if possible, should be referred to a nephrologist.

-

○

Aldosterone excess: this is suggested by hypokalemia during the initial evaluation, although this condition can occur even when potassium levels appear normal. About 20% of patients whose blood pressures remain high despite taking 3 drugs have evidence of aldosterone excess. Confirming this diagnosis usually requires assistance from clinical hypertension specialists.

-

○

Sleep apnea: This is common in obese patients. Not all patients with sleep apnea have hypertension but there is a clear association. A preliminary diagnosis can be made by finding a history of snoring during sleep and daytime tiredness. A definitive diagnosis usually requires a sleep laboratory study.

-

○

Other secondary causes of hypertension such as renal artery stenosis or coarctation of the aorta usually require evaluation by a specialist.

Final Comment

The authors of this statement acknowledge that there are insufficient published data from clinical trials in hypertension to create recommendations that are completely evidence‐based, and so inevitably some of our recommendations reflect expert opinion and experience.

We also should point out that because of the major differences in resources among points of care it is not possible to create a uniform set of guidelines. For this reason we have written a broad statement on the management of hypertension and have not presumed to anticipate the conditions or shortfalls that might exist in particular communities. We expect that experts who are familiar with local circumstances will feel free to use their own judgment in modifying our recommendations and to create practical instructions to help guide front‐line practitioners in providing the best care possible.

A Note to Colleagues

The authors of this statement would welcome comments and suggestions from colleagues. We recognize that in this initial version of the guidelines there will probably be omissions, redundancies, and inaccuracies. Please feel free to get in touch with us either by letters to the Journal or by personal communication.

Disclosures

MAW: Research funding: Medtronics. Consulting: Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Novartis, Daichi Sankyo, Takeda, Forest. Speaker: Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda, Forest. ELS: Research Funding: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada Research Chairs program of CIHR/Government of Canada, Servier France. Consultant: Servier, Novartis. Speaker: Forest Canada, Pfizer Japan. WBW: Research Funding: National Institutes of Health. Consulting: Safety Committees (DSMB, CEC, Steering Committees); Ardea Biosciences, Inc.; AstraZeneca; Dendreon, Forest Research Institute, Inc.; Roche; St. Jude's Medical, Takeda Global Research, Teva Neuroscience. SM, LHL, JGK, BJM, DLC, JCC, RRJC, ST, AJR, AES, RMT: No conflicts of interest. JMF: Research Funding: Novartis, Medtronic. Consultant: Novartis, Medtronic, Back Beat Hypertension. BLC: Research Funding: NIH and VA. VSR: Consultant: Medtronic, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Forest. DK: Research Funding: Medtronic. RT: Research Funding: NIH. Consultant: Medtronic, Janssen, Merck, GSK. JC: Research Funding and Speaker: Servier in relation to ADVANCE trial and Post‐trial study. GLB: Research Funding: Takeda. Consultant: Takeda, AbbVie, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Novartis, CVRx, Medtronic, Relypsa, Janssen, BMS. JW: Consultant and Speaker: Boehringer‐Ingelheim, MSD, Novartis, Omron, Pfizer, Servier, and Takeda. JDB: Research and Consultant: CVRx. DS: Research: Medtronic, CVRx. Consultant: Takeda, UCB, Novartis, Medtronic, CVRx. Speaker: Takeda. SBH: Speaker: Novartis, Servier.

Acknowledgments

This statement was written under the sponsorship of the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. In addition, the Asia Pacific Society of Hypertension has endorsed these guidelines. The statement was prepared without any external funding. The work and time of the authors was provided by them entirely on a volunteer basis.

Suggested Reading

- 1. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flack JM, Sica DA, Bakris G, et al. Management of high blood pressure in Blacks: an update of the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks consensus statement. Hypertension. 2010;56:780–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Health Care Evidence . CG127. Hypertension: Clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. On‐line: NICE Clinical Guidelines. February 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18‐month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:485–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. SHEP Cooperative Research Group . Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . The Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weber MA, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Blood pressure dependent and independent effects of antihypertensive treatment on clinical events in the VALUE Trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2049–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Redon J, Mancia G, Sleight P, et al. Safety and efficacy of low blood pressures among patients with diabetes: subgroup analyses from the ONTARGET (ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weber MA, Bakris GL, Hester A, et al. Systolic blood pressure and cardiovascular outcomes during treatment of hypertension. Am J Med. 2013;126:501–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cooper‐DeHoff RM, Gong Y, Handberg EM, et al. Tight blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients withdiabetes and coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2010;304:61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. ACCORD Study Group ; Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood‐pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents ; Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC, et al; Single‐drug therapy for hypertension in men. A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:914–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group . Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascluar and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, et al. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peralta CA, Norris KC, Li S, et al. Blood pressure components and end stage renal disease in persons with chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weir MR, Bakris GL, Weber MA, et al. Renal outcomes in hypertensive Black patients at high cardiovascular risk. Kidney Int. 2012;81:568–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weber MA, Jamerson K, Bakris GL, et al. Effects of body size and hypertension treatments on cardiovascular event rates: subanalysis of the ACCOMPLISH randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2008;51:1403–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shivalkar B, Van de Heyning C, Kerremans M, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: more insights on structural and functional cardiac alterations, and the effects of treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]