Abstract

Inter‐arm blood pressure difference (IAD) is recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality. Its reproducibility in the elderly is unknown. The authors determined the prevalence and reproducibility of IAD in hospitalized elderly patients. Blood pressure was measured simultaneously in both arms on two different days in elderly individuals hospitalized in a geriatric ward. The study included 364 elderly patients (mean age, 85±5 years). Eighty‐four patients (23%) had systolic IAD >10 and 62 patients (17%) had diastolic IAD >10 mm Hg. A total of 319 patients had two blood pressure measurements. Systolic and diastolic IAD remained in the same category in 203 (64%) and 231 (72%) patients, respectively. Correlations of systolic and diastolic IAD between the two measurements were poor. Consistency was not affected by age, body mass index, comorbidities, or treatment. IAD is extremely common in hospitalized elderly patients, but, because of poor consistency, its clinical significance in this population is uncertain.

It is recommended to measure blood pressure (BP) in both arms at initial evaluation1 because differences exist in BP values measured in both arms and measurement in only one arm may lead to underdiagnosis of hypertension.2, 3 Inter‐arm BP difference (IAD) has received increasing attention in recent years because it has been found to be associated with peripheral vascular disease4 and was identified as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity.5, 6 The prevalence of systolic IAD >10 mm Hg in the general population ranges from 14% to 23.6%5, 7 and several reports show no association between IAD and age.8, 9 The significance of hypertension as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality decreases in the elderly,10 but IAD in the elderly has been found to be associated with increased mortality, similar with the general population.11 Because of the increasing awareness of IAD, it is important to evaluate its true prevalence and reproducibility. IAD has been reported to be reproducible in some studies,12 yet, in other studies, reproducibility was noted only in patients with a history of obstructive arterial disease.13 The reproducibility of IAD in elderly patients, who likely represent those with the most significant burden of peripheral vascular disease, is unknown. This study evaluated a cohort of hospitalized elderly patients for the prevalence and reproducibility of IAD with repeated measurements.

Methods

Study Population

All elderly individuals hospitalized in the geriatric ward at the Rabin Medical Center, Beilinson Campus in Isreal between October 2012 and October 2013 were screened for eligibility to be included in the study. Our geriatric ward is a 30‐bed ward that admits patients older than 65 years with various acute medical problems.

Patients who were expected to survive less than 24 hours from admission and patients with systolic BP (SBP) <90 mm Hg on admission were excluded from the study. Also excluded were patients in whom simultaneous BP measurement could not be performed or patients who did not give informed consent to participate in the study. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Rabin Medical Center and all patients signed an informed consent.

BP Measurement and Data Collection

BP measurement was performed by a designated technician in a quiet room with the patient in the supine position following at least 5 minutes of rest. Measurements were performed at noon before lunch. BP was measured simultaneously in both arms with two standard sphygmomanometers (Vital Signs Monitor 52 NTP model; Welch Allyn Protocol Inc, Beaverton, OR) calibrated according to the manufacturer's recommendations. During the hospitalization, two measurements were performed: the first during admission or within 24 hours of admission and the second during the course of hospitalization (2–7 days after the first measurement). Standard or large cuffs were used as appropriate.

Medical history and patients' characteristics retrieved from the patients' medical records included age, sex, body mass index, and comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease). Laboratory parameters evaluated included serum glucose, lipid profile, and creatinine level.

Statistical Analysis

Systolic IAD was defined as the difference in absolute values between SBP in the right arm and SBP in the left arm. Diastolic IAD was defined as the difference in absolute values between diastolic BP (DBP) in the right arm and DBP in the left arm. IAD was arbitrarily divided into 4 categories (0–1 mm Hg, 2–5 mm Hg, 6–10 mm Hg, and >10 mm Hg). Results are reported as mean±standard deviation for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Chi‐square and independent t tests were calculated to test differences between sexes in categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

To test the hypothesis that there is a linear relationship between the two times measurements (with ordered categories as previously described), the Mantel‐Haenszel linear‐by‐linear association chi‐square test was applied. Pearson's correlation test was used to evaluate the association between IAD and all evaluated continuous variables, while independent t test was used to evaluate the association between IAD and all evaluated dichotomous variables. To examine the agreement between the first and the second IAD, the Bland‐Altman approach was applied. The differences between the measurements were plotted against their mean, displaying the level of agreement between the two measurements. The level of agreement was assessed by calculating the bias, estimated by the mean difference and the standard deviation of the differences. McNemar's test to categorize the IAD to below and above 10 mm Hg was used to further examine the agreement between measurements. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients' Characteristics

During the study period, 1600 elderly patients were hospitalized in the geriatric department. Of these patients, 364 (160 men) with a mean age of 85±5 years were eligible to be included in the study. Most patients had hypertension and more than a third had diabetes mellitus and ischemic heart disease (Table 1). The most common antihypertensive medications used were β‐blockers and calcium antagonists.

Table 1.

Patients' Characteristics

| Parameter | All Patients | Men | Women | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 364 | 160 | 204 | |

| Age, y | 85±5 | 85±5 | 85±5 | .669 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24±6 | 23±5 | 24±6 | .066 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 135±21.5 | 133±21 | 137±22 | .158 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 69±13 | 68±13 | 69±13 | .483 |

| Heart rate, beats per min | 74±14 | 72±14 | 75±14 | .020 |

| Associated diseases, No. (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 134 (37) | 60 (38) | 74 (36) | .810 |

| Hypertension | 283 (78) | 122 (76) | 161 (79) | .543 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 125 (34) | 71 (44) | 54 (27) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 78 (21) | 45 (28) | 33 (16) | .006 |

| Laboratory parameters, mg/dL | ||||

| Serum fasting glucose | 143±60 | 144±65 | 141±57 | .667 |

| LDL cholesterol | 92±31 | 87±28 | 96±33 | .007 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.12±0.68 | 1.33±0.82 | 0.96±0.40 | <.001 |

| Treatment, No. (%) | ||||

| β‐Blockers | 159 (44) | 63 (39) | 96 (47) | .131 |

| Calcium antagonists | 156 (43) | 61 (38) | 95 (47) | .097 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 147 (40) | 68 (43) | 79 (39) | .490 |

| Diuretics | 133 (37) | 57 (36) | 76 (37) | .722 |

| α‐Blockers | 76 (21) | 64 (40) | 12 (6) | <.001 |

| Statins | 212 (58) | 94 (59) | 118 (58) | .862 |

| Aspirin | 166 (46) | 85 (53) | 81 (40) | .015 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Women had higher heart rate, higher levels of low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, and lower levels of serum creatinine than men (Table 1). Women used fewer α‐blockers and less aspirin, and were less likely to have ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease than men (Table 1).

Inter‐Arm Differences

The IAD among the study population is depicted in Table 2. Eighty‐four patients (23.1%) had systolic IAD >10 mm Hg. The prevalence of systolic IAD >10 mm Hg was almost the same in both the men and the women. Sixty‐two patients (17%) had diastolic IAD >10 mm Hg. The prevalence of diastolic IAD >10 mm Hg was 2‐fold higher in women than in men (Table 2; P<.05). In 177 patients (49%), SBP was higher in the right arm and in 165 patients (45.3%) it was higher in the left arm. In 174 patients (47.8%), DBP was higher in the right arm and in 155 patients (42.6%) it was higher in the left arm. Systolic IAD was significantly higher in patients treated with calcium antagonists compared with those who were not treated with these agents (8.3±0.6 vs 6.7±0.4 mm Hg; P=.002). SBP, age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, and use of other classes of antihypertensive agents were not associated with either systolic or diastolic IAD.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Systolic and Diastolic Inter‐Arm Differences by Categories and Sex

| Category | 0–1 | 2–5 | 6–10 | >10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic inter‐arm BP difference, mm Hg | ||||

| All patients | 56 (15.4) | 112 (30.8) | 112 (30.8) | 84 (23.1) |

| Men | 30 (18.8) | 47 (29.4) | 49 (30.6) | 34 (21.2) |

| Women | 26 (12.7) | 65 (31.9) | 63 (30.9) | 50 (24.5) |

| Diastolic inter‐arm BP difference, mm Hg | ||||

| All patients | 77 (21.2) | 131 (36.0) | 94 (25.8) | 62 (17.0) |

| Men | 39 (24.4) | 63 (39.4) | 40 (25.0) | 18 (11.3) |

| Women | 38 (18.6) | 68 (33.3) | 54 (26.5) | 44 (21.6)a |

Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure. Values are expressed as numbers (percentages). a P<.05 vs men.

IAD Consistency

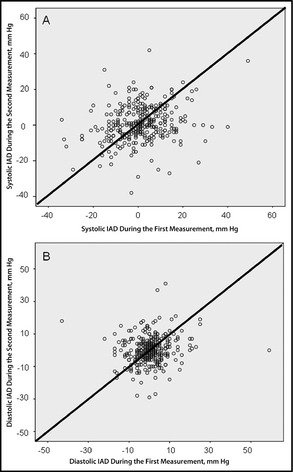

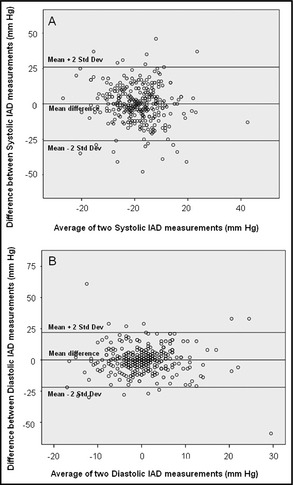

In 45 patients, a second BP measurement was not recorded because the patients died (n=5) or withdrew consent (n=40). Among 319 patients with two BP measurements, values were similar in the first and second measurements (Table 3; P=not significant [ns]). Systolic IAD persisted in the same range in 203 patients (64%) and diastolic IAD persisted in the same range in 231 patients (72%) (Table 4; P=ns). Systolic IAD >10 mm Hg was consistent in 38% and diastolic IAD >10 mm Hg was consistent in 24% of the patients (Table 4). Of patients with systolic IAD >10 mm Hg in the first measurement, 9.2% had equal SBP values in both arms in the second measurement. Correlations of systolic IAD and diastolic IAD between the first and the second measurements were poor (Figure 1; R for systolic IAD 0.153 and for diastolic IAD 0.124). The agreement between the first and second systolic and diastolic IAD was poor, with discrepancies of more than 25 mm Hg, as can be seen in the Bland‐Altman plot in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Mean Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure Levels in Both Arms on Two Measurements

| Systolic | Diastolic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | Difference | Right | Left | Difference | |

| First measurement, mm Hg | 135±22 | 134±21 | 1.04±10.0 | 69±13 | 69±12 | 0.31±8.4 |

| Second measurement, mm Hg | 133±20 | 132±20 | 1.18±11.2 | 68±11 | 67±11 | 0.39±8.4 |

| Difference between the two measurements, mm Hg | 2.0±21 | 2.1±21 | −0.14±13.1 | 1.23±12.4 | 1.31±12.0 | −0.08±11.1 |

P for all paired comparisons >.05 (no significant differences between arm and between measurements).

Table 4.

Categories of IAD on the First and Second Measurements

| Systolic IAD | Diastolic IAD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Measurement IAD ≤10 mm Hg | Second Measurement IAD >10 mm Hg | No. | Second Measurement IAD ≤10 mm Hg | Second Measurement IAD >10 mm Hg | No. | |

| First measurement IAD ≤10 mm Hg | 174 (72%) | 69 (28%) | 243 | 218 (83%) | 46 (17%) | 264 |

| First measurement IAD >10 | 47 (62%) | 29 (38%) | 76 | 42 (76%) | 13 (24%) | 55 |

| P valuea | .08 | .203 | ||||

Abbreviation: IAD, inter‐arm blood pressure difference.

McNemar's test for paired samples.

Figure 1.

Correlation between systolic (A) and diastolic (B) inter‐arm blood pressure differences (IAD) in the first measurement and the second measurement (R for systolic IAD is 0.153 and for diastolic IAD is 0.124).

Figure 2.

Bland‐Altman plot for systolic (A) and diastolic (B) inter‐arm blood pressure differences (IAD). The bias between the measurements can be seen by the points that fall out of the limit of agreements (mean±2 standard deviations).

Consistency of either systolic or diastolic IAD was not affected by age, sex, BMI, comorbidities, or antihypertensive treatment.

Discussion

The prevalence of systolic IAD in this study was high (23%). Although some studies of IAD report similar and even higher rates of systolic IAD, the prevalence of systolic IAD >10 mm Hg has been reported to be 14% in a large meta‐analysis.7 This high prevalence of systolic IAD is even more remarkable as BP was measured simultaneously, which has been reported to decrease IAD.7, 14 Evidence regarding IAD prevalence in the elderly is scarce. Sheng and colleagues11 reported a low prevalence of IAD when measured simultaneously in elderly men (5.6%) and women (7.6%). Another report found an even lower rate of IAD in a cohort of elderly individuals.15 The high IAD reported in our study may be attributed to the high burden of atherosclerosis in our patients as a result of their older age and high prevalence of comorbidities.

In our study, systolic IAD >10 mm Hg was the same in both sexes, but diastolic IAD >10 mm Hg was 2‐fold more prevalent in women than in men. IAD was reported to be more prevalent in women in two Chinese studies,11, 16 but other studies failed to prove an association between sex and IAD.17, 18 This study supplies additional proof to the lack of effect of sex on systolic IAD.

Previous reports have shown a bias toward higher BP readings from the right arm,3, 18, 19 whereas other reports failed to show such a tendency.4, 6, 20 Our study did not show any bias toward either arm, thus emphasizing the importance of BP measurement in both arms to identify the arm with the higher BP measurement in which future BP measurements should be performed.

IAD has been found to be associated with various factors including BMI21 and a history of ischemic heart disease.22 In our study, we failed to show an association between demographic factors evaluated and the magnitude of IAD. This may be due to the fact that the study population probably had such extensive atherosclerosis that additional factors associated with IAD contributed very little, if at all, to IAD. The only factor found to be associated with IAD in the present study was use of calcium antagonists. No previous study has evaluated the association between the use of various antihypertensive agents and IAD. Calcium antagonists may be used in patients with more severe atherosclerosis, yet this hypothesis requires further confirmation.

IAD has recently been identified as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality and was found to be associated with poor prognosis.4, 5, 6 As a prognostic marker it must be reproducible, yet there is little information regarding IAD reproducibility. Although multiple BP readings were associated with a lower prevalence of IAD in a previous meta‐analysis,7 this meta‐analysis as well as other studies published later14 referred only to multiple measurements performed during the same visit. Two studies evaluated IAD reproducibility, but, in both, BP measurements were done sequentially rather than simultaneously. Agarwal and colleagues12 reported high between‐visit IAD reproducibility when BP measurements were taken 1 week apart. In another study, the IAD reproducibility was low except for in two patients with obstructive arterial disease.13 We found poor reproducibility between IAD. This is the first report in which between‐visit IAD reproducibility was evaluated in hospitalized elderly patients.

Elderly individuals are a unique cohort that deserves a specific study because the burden of cardiovascular risk factors in this population is significantly higher than in younger individuals for which the clinical significance of IAD has been extensively evaluated. In addition, this population has a much higher rate of white‐coat hypertension that may influence the rate of IAD.23 Although this study evaluated only hospitalized patients, who may not be representative of the general elderly population, it seems that this cohort is representative of the elderly population as the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus was similar to that reported previously.24, 25 Thus, it would seem that the low IAD reproducibility reported here raises concern regarding the prognostic significance of IAD in the general elderly population. Because previous studies have noted an association between IAD and mortality, it is possible that it is more reproducible and has greater significance in young individuals. Long‐term follow‐up was not performed in this study and thus the true clinical significance of IAD in elderly individuals is yet unknown. Nevertheless, the poor reproducibility of this variable in the elderly raises concern about its importance in this population.

Study Strengths

The main strengths of our work are the relatively large cohort of elderly patients, the simultaneous BP measurements, which is certainly the most accurate method to diagnose IAD,7 and the performance of IAD measurement on consequent days enabling to evaluate IAD reproducibility. We performed all measurements at the same time of day and before meals in order to avoid BP changes reported to occur following meals.26, 27 Evaluation of these variables in an elderly population makes this study even more unique as IAD data are scarce in this age group.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in hospitalized patients in whom the acute condition leading to their hospitalization may have influenced the BP values. In order to minimize the effect of hemodynamic instability on IAD, we excluded all patients with admission BP <90 mm Hg. In addition, the BP measured on admission and the BP recorded during the second measurement were not significantly different and, thus, we believe that the influence of the underlying condition leading to hospitalization was negligible. Second, this study was performed in hospitalized elderly individuals, making it difficult to apply the results to the general population. Because patient characteristics were similar to those of previous studies in elderly individuals reported in the literature, we believe that the results may be applicable to the general elderly population. An additional limitation of this study is the fact that the simultaneous BP measurements were recorded with two different instruments. Although we attempted to operate both devices at the exact same time, there may have been minimal timing differences between the two BP measurements that may have contributed to the inconsistencies in IAD, as was reported previously.14, 28 Another potential bias is the interval between the measurements. Indeed the interval between the measurements was 2 to 7 days, but, in most patients, the second measurement was performed 2 days after the first and the BP values were similar between the two measurements. Therefore, we believe that this should not have influenced the consistency.

Conclusions

IAD in the elderly is extremely common but its reproducibility is poor. Therefore, its significance in this population is uncertain.

Disclosure

None.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:518–523. ©2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. O'Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, et al. European Society of Hypertension recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and home blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2003;21:821–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clark CE, Campbell JL, Evans PH, Millward A. Prevalence and clinical implications of the inter‐arm blood pressure difference: a systematic review. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lane D, Beevers M, Barnes N, et al. Inter‐arm differences in blood pressure: when are they clinically significant? J Hypertens. 2002;20:1089–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clark CE, Campbell JL, Powell RJ, Thompson JF. The inter‐arm blood pressure difference and peripheral vascular disease: cross‐sectional study. Fam Pract. 2007;24:420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, Campbell JL. The difference in blood pressure readings between arms and survival: primary care cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, et al. Association of a difference in systolic blood pressure between arms with vascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verberk WJ, Kessels AG, Thien T. Blood pressure measurement method and inter‐arm differences: a meta‐analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:1201–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fotherby MD, Panayiotou B, Potter JF. Age‐related differences in simultaneous blood pressure measurements. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69:194–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kimura A, Hashimoto J, Watabe D, et al. Patients characteristics and factors associated with inter‐arm difference of blood pressure measurements in a general population in Ohsama, Japan. J Hypertens. 2004;22:2277–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Bemmel T, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, Blauw GJ. In a population based prospective study, no association between high blood pressure and mortality after age 85 years. J Hypertens. 2006;24:287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sheng CS, Liu M, Zeng WF, et al. Four‐limb blood pressure as predictors of mortality in elderly chinese. Hypertension. 2013;61:1155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agarwal R, Bunaye Z, Bekele DM. Prognostic significance of between‐arm blood pressure differences. Hypertension. 2008;51:657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eguchi K, Yacoub M, Jhalani J, et al. Consistency of blood pressure differences between the left and right arms. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:388–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van der Hoeven NV, Lodestijn S, Nanninga S, et al. Simultaneous compared with sequential blood pressure measurement results in smaller inter‐arm blood pressure differences. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15:839–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hashimoto F, Hunt WC, Hardy L. Differences between right and left arm blood pressures in the elderly. West Med J. 1984;141:189–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Su HM, Lin TH, Hsu PC, et al. Association of interarm systolic blood pressure difference with atherosclerosis and left ventricular hypertrophy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karagiannis A, Tziomalos K, Krikis N, et al. The unilateral measurement of blood pressure may mask the diagnosis or delay the effective treatment of hypertension. Angiology. 2005;56:565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singer AJ, Hollander JE. Blood pressure. Assessment of interarm differences. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2005–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cassidy P, Jones K. A study of inter‐arm blood pressure differences in primary care. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:519–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grossman A, Prokupetz A, Gordon B, et al. Inter‐arm blood pressure differences in young, healthy patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15:575–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arnett DK, Tang W, Province MA, et al. Interarm differences in seated systolic and diastolic blood pressure: the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network study. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1141–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Igarashi Y, Chikamori T, Tomiyama H, et al. Clinical significance of inter‐arm pressure difference and ankle‐brachial pressure index in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Cardiol. 2007;50:281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bulpitt CJ, Beckett N, Peters R, et al. Does white coat hypertension require treatment over age 80? Results of the hypertension in the very elderly trial ambulatory blood pressure side project. Hypertension. 2013;61:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gao Y, Chen G, Tian H, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in China: a cross‐sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stolk RP, Pols HA, Lamberts SW, et al. Diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance, and hyperinsulinemia in an elderly population. The Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zanasi A, Tincani E, Evandri V, et al. Meal‐induced blood pressure variation and cardiovascular mortality in ambulatory hypertensive elderly patients: preliminary results. J Hypertens. 2012;30:2125–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weiss A, Grossman E, Beloosesky Y, Grinblat J. Orthostatic hypotension in acute geriatric ward: is it a consistent finding? Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2369–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mejia AD, Egan BM, Schork NJ, Zweifler AJ. Artefacts in measurement of blood pressure and lack of target organ involvement in the assessment of patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]