Abstract

Background

To establish successful strategies and increasing the utilization of preventive services, there is a need to explore the extent to which the general female population is aware and use the service for cervical cancer-screening among women infected with HIV in Africa. Available evidences in this regard are controversial and non-conclusive on this potential issue and therefore, we estimated the pooled effect of the proportion of knowledge, attitude and practice of HIV infected African women towards cervical cancer screening to generate evidence for improved prevention strategies.

Methods

We applied a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies conducted in Africa and reported the proportion of knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer screening. We searched electronic databases: PubMed/Medline, SCOPUS, ScienceDirect, Web of science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and allied Health Sciences (CINAHL) and Google scholar databases to retrieve papers published in English language till August 2020. We used random-effects model to estimate the pooled effect, and funnel plot to assess publication bias. The registration number of this review study protocol is CRD42020210879.

Results

In this review, we included eight published papers comprising 2,186 participants. The estimated pooled proportion of knowledge of the participants was 43.0% (95%CI:23.0–64.0) while the pooled estimates of attitudes and practices were 38.0% (95%CI: 1.0–77.0) and 41.0% (95%CI: 4.0–77.0), respectively. The proportion of the outcome variables were extremely heterogeneous across the studies with I2> 98%).

Conclusion

The pooled estimates of knowledge, attitude and practice were lower than other middle income countries calls for further activities to enhance the uptake of the services and establish successful strategies.

Introduction

Cancer of the cervix uteri is the 3rd most common cancer among women worldwide, with an estimated 569,847 new cases and 311,365 deaths with a greater number of cases (119,284) and deaths (81,687) in Africa, according to the(GLOBOCAN 2018, an online database providing estimates of incidence and mortality) [1]. This death report is even higher than worldwide report in 2012 indicating that 266,000 women died of cervical cancer–equivalent of one woman dying every 2 minutes with about 90% of these deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries [2].

Cancer of the cervix is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer after breast cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death after breast and lung cancers in developing countries [3]. It also ranks second next to breast cancer in Ethiopia [4].

One of the strategies to minimize the burden of the disease is to establish successful strategies and increasing the utilization of preventive measures ranging from community education, social mobilization, vaccination, screening, and treatment to palliative care [5].

Most importantly, increasing the knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of cervical cancer screening and prevention among females is a part of a comprehensive approach to cervical cancer prevention and control strategy. This might play a pivotal role in the controlling strategy on the issue. Health workers considered to take a lead in this regard are found to have less knowledge about cervical cancer as a disease and relatively fair knowledge on Pap smear testing [6]. Among women who had been attending a tertiary hospital, the majority had a positive attitude while about a third had good knowledge and very few (2.7%) had good practice [7]. When looked at the patients suffered gynecological cancer, more than half of them knew that their disease was malignant [8]. In addition, different evidence about knowledge, attitude and practice were generated at different corners of Asian countries [9–12] that seek for pooling of the findings for decision making.

In Africa, the findings indicate that the cervical cancer screening approach is in its infancy stage. For instance, in rural Uganda, only 4.8% of women had ever been screened for cervical cancer [13] and around ten percent in Burkina-Faso [14]. In Ethiopia, including University female students, their KAP is fair towards cervical cancer and scored less than fifty percent [15–18].

On the basis of the comprehensive literature search made, variability on the KAP score prevails in various African countries and assumed to have high prevalence of the problem and with unavailability of information among the female population living with HIV who are the most vulnerable population.

Therefore, this review aims to estimate the pooled effect of the proportion of KAP of HIV infected African women towards cervical cancer screening to generate evidence for improved prevention strategies.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and screening of papers

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of published articles to estimate the pooled effect or the proportion of knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer screening in Africa. We systematically searched the papers published in the following electronic databases; PubMed/Medline, SCOPUS, ScienceDirect, Web of science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and allied Health Sciences (CINAHL) and Google scholar. The review was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standard [19] as displayed in S1 Table. We used a search strategy by combining the following key terms: knowledge, attitude, practice, cervical cancer, uterine cervical neoplasms, cervical cancer screening, human immunodeficiency virus or HIV, and Africa. We used Truncation(*) to manage spelling variation during search: infect* or positive, wom*n or female* or girl*. We used both free text and Medical subject heading [MeSH]terms during electronic database search.

PubMed database search strategy was: (((((((knowledge) AND ((((cervical cancer) OR (Uterine Cervical Neoplasms)) OR (cervical cancer screening[tiab])) OR (cervical cancer screening[MeSH Terms]))) AND ((Attitude) AND ((((cervical cancer) OR (Uterine Cervical Neoplasms)) OR (cervical cancer screening[tiab])) OR (cervical cancer screening[MeSH Terms])))) AND ((practice) AND ((((cervical cancer) OR (Uterine Cervical Neoplasms)) OR (cervical cancer screening[tiab])) OR (cervical cancer screening[MeSH Terms])))) AND ((human immunodeficiency virus) OR (HIV))) AND ((infect*) OR (positive))) AND ((women) OR (female*))) AND (Africa) AND ((y_10[Filter]) AND (female[Filter]) AND (english[Filter]))

The search was repeated to identify the consistency of search terms and result. Two authors (AL and JH) independently reviewed the titles, abstracts and full articles of retrieved studies.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

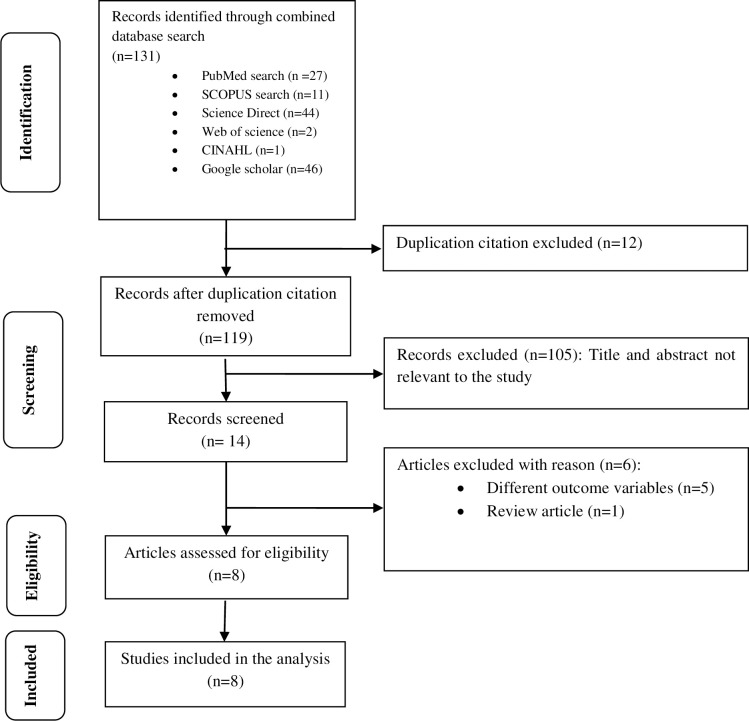

In this review, we included a cross sectional studies conducted in Africa that reported Knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer screening. The inclusion was restricted to papers published from 2010 to August 2020 in the English language within a ten year period though data were available from 2014 to 2019. We excluded those studies that did not clearly state the outcome measures, study population different from HIV infected women or females, duplication citations, and review articles [Fig 1].

Fig 1. Flow diagram of studies reviewed, screened and included.

Study quality assessment

We assessed the quality of included studies by using the 14 items Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies—NHLBI, NIH [20]. This assessment tool mainly focused on research question, study population, eligibility criteria (inclusion and exclusion criteria of study participants), sample size justification, exposure measures and assessment, sufficient time frame to see an effect, outcome measures and blinding of outcome assessors, follow up rate, and statistical analysis. The quality assessment was rated as good, fair and poor based on quality assessment tool criteria. The maximum score indicating high quality was 14 and the lowest possible score was zero. The rating values of the included studies in terms of their quality were based on their design. Cross-sectional types do not consider the items which fit for cohort and taken as not-applicable (NA) and thus, the rating values were not taken from the possible maximum score (i.e. 14). In this review, all scores are written in percentage beside the results individual components of the quality assessment [S2 Table].

Data extraction

We extracted data from eligible abstract and/or full text of the articles by considering the outcome variables and the characteristics of participants such as age range, mean or median age, sex, HIV sero-status. In addition, we extracted the study characteristics such as first author, year of publication, study setting, study location or country, study design, sample size, knowledge score, attitude and practice [Table 1].

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies to estimate the pooled effect of knowledge, attitude and practice of HIV-infected women towards cervical cancer in Africa.

| First Author | Year | Study setting | Study location | Study design | Sample size | Knowledge | Attitude | Practice | Age range/mean age in years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solomon et al [24] | 2019 | Health facility | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 475 | 119 | 36 | ||

| Shiferaw et al [25] | 2018 | Health facility | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 581 | 136 | 35 | ||

| Mitchell et al [26] | 2017 | Health facility | Uganda | Cross-sectional | 87 | 1 | 30–69 | ||

| Stuart et al [27] | 2019 | Health facility | Ghana | Qual-Quantof parent cohort | 60 | 48 | > = 18 | ||

| Adibe & Aluh [28] | 2017 | Health facility | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 447 | 45 | 194 | > = 9 | |

| Belglaiaa et al [29] | 2018 | Health facility | Morocco | Cross-sectional | 115 | 24 | 15 | 34.9 | |

| Rosser et al [30] | 2015 | Health facility | Kenya | Cross-sectional | 106 | 69 | 74 | 89 | 34.9 |

| Maree & Moitse [31] | 2014 | Health facility | South Africa | Cross-sectional | 315 | 198 | 38.9 |

The proportions of knowledge, attitude and practice is written in number to make the data which fit for meta-analysis using metaprop.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the pooled proportion of knowledge, attitude and practice of HIV positive women on cervical cancer screening with its 95% Confidence Interval (CI) using random effects meta-analysis model assuming the true effect size varies between studies [21]. The proportion of knowledge, attitude and practice reported in each included study is multiplied by its sample size to express the score in number, and data presented in forest plot.

We assessed heterogeneity in the proportions of different studies using heterogeneity Chi-square (x2) based Q test with significant level of p-value < 0.1 and I2. The I2value 25% indicates low heterogeneity while 50% moderate and 75% high [22]. We assessed the potential publication bias using funnel plot. If the 95% of the point estimates of the included studies lie within the funnel plot defined by straight lines, then that indicates the absence of heterogeneity [23]. We used moment based meta-regression to assess the potential source of heterogeneity. Data analysis was conducted using STATA version 14.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Since the review made was based on previously published articles, there was no need for ethical clearance. Nevertheless, the protocol of the study was pre-registered on PROSPERO (International prospective register of systematic reviews) University of York, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination with registration number CRD42020210879.

Operational definition of KAP in this protocol

Knowledge (K). Refers to the awareness of HIV positive women towards cervical cancer screening in Africa. Different pocket studies are filtered and eligible articles are included in the analysis to estimate the pooled knowledge.

Attitude (A). Refers to the way of thinking or feeling of HIV positive women on cervical cancer screening.

Practice (P). Refers to the habit of women to be screened for cervical cancer.

Results

Study characteristics

We included eight studies [Fig 1], from Ethiopia [24, 25], Uganda [26], Ghana [27], Nigeria [28], Morocco [29], Kenya [30], and South Africa [31] which are health facility based [Table 1]. Almost all the included studies were cross-sectional types published from 2014 to 2019 though the extraction of data was done for the past ten years till August 2020. The maximum sample size reported was 581 [25] while the minimum was 60 [27]. The age of respondents ranged from 9 to 69 years [Table 1].

Pooled estimates of knowledge of HIV positive women towards cervical cancer screening in Africa

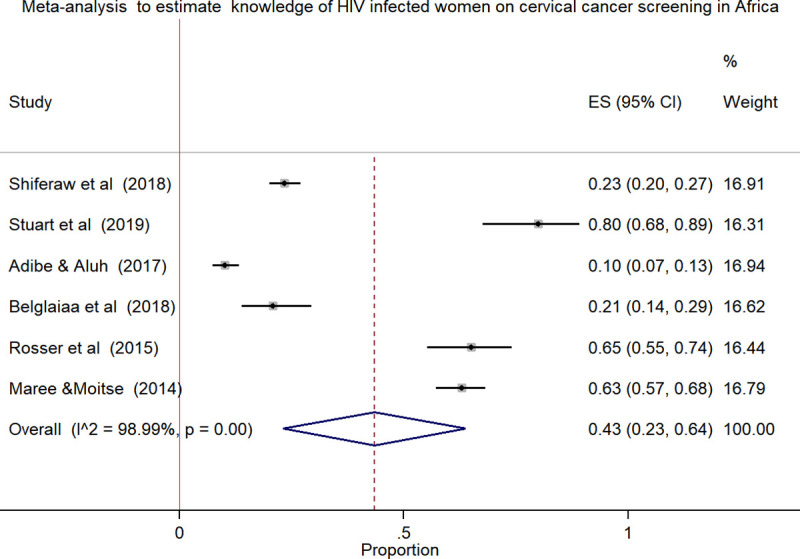

We pooled data from 2,186 HIV positive women to estimate the pooled proportion of knowledge on cervical cancer screening using meta-analysis. The overall pooled proportion of knowledge was 43.0% [Fig 2] with high heterogeneity across the studies(chi2 = 493.23 (d.f. = 5), p = 0.001, and I2 = 98.99%).

Fig 2. Forest plot to estimates the proportion of knowledge among HIV infected women towards cervical cancer screening in Africa with 95% CI (the estimate weighted based on random effects model): ES-Effect size equivalent to the proportion, CI-Confidence interval.

In the plot, the diamond shows the pooled result and the boxes show the effect estimates from the single studies. The purple dotted vertical line indicates pooled estimate. The purple solid vertical line indicates the reference line at zero indicating no effect. The horizontal line through the boxes illustrate the length of the confidence interval and the boxes show the effect estimates from the single studies.

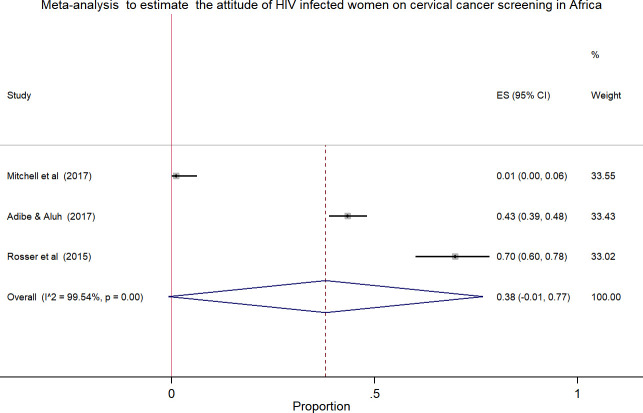

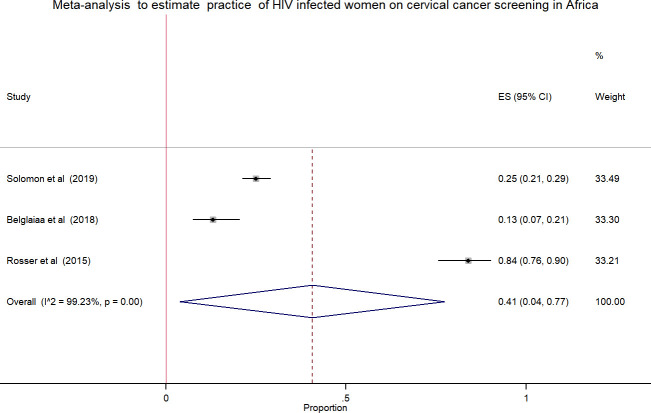

Pooled estimates of the attitude and practice of HIV positive women towards cervical cancer screening in Africa

Meta-analysis using few studies included is not recommended due to less precision. In this review, only three studies included in the analysis to estimate the pooled effect, which was the attitude and practice of HIV positive women towards cervical cancer screening. The pooled estimates of attitude was 38.0% [Fig 3] with high heterogeneity across the studies (chi2 = 437.57 (d.f. = 2), p = 0.001, I^2 (variation in ES attributable to heterogeneity) = 99.54%) while the pooled practice estimate was 41.0% [Fig 4] with high level of heterogeneity (chi2 = 260.80 (d.f. = 2), p = 0.001, I^2 (variation in ES attributable to heterogeneity) = 99.23%).

Fig 3. Forest plot to estimates the proportion of attitude among HIV infected women towards cervical cancer screening in Africa with 95% CI (the estimate weighted based on random effects model): ES-Effect size equivalent to the proportion, CI-Confidence interval.

In the plot, the diamond shows the pooled result and the boxes show the effect estimates from the single studies. The purple dotted vertical line indicates pooled estimate. The purple solid vertical line indicates the reference line at zero indicating no effect. The horizontal line through the boxes illustrate the length of the confidence interval and the boxes show the effect estimates from the single studies.

Fig 4. Forest plot to estimates the proportion of practice among HIV infected women towards cervical cancer screening in Africa with 95% CI (the estimate weighted based on random effects model): ES-Effect size equivalent to the proportion, CI-Confidence interval.

In the plot, the diamond shows the pooled result and the boxes show the effect estimates from the single studies. The purple dotted vertical line indicates pooled estimate. The purple solid vertical line indicates the reference line at zero indicating no effect. The horizontal line through the boxes illustrate the length of the confidence interval and the boxes show the effect estimates from the single studies.

Meta-regression analysis

We assessed the effect of sample size and year of the study on heterogeneity between the studies using meta-regression model. However, there was no significant prediction of heterogeneity between the effect size and the assessed variables (i.e., both sample size and year of the study) [Table 2]. Meaning, in the adjusted model, both sample size and year of the study didn’t indicate heterogeneity in the effect size which is equivalent to the pooled proportion (P > 0.05). When we interpret the finding using β-coefficient, one unit increase in the publication year will decrease the outcome variable by the coefficient of 20.14 points and an increase in the sample size will depict a slight increase (0.14 points) in the outcome [Table 2].

Table 2. Meta-regression analysis for year of study and sample size as a reason of heterogeneity on the knowledge estimates of women infected by HIV in Africa.

| Variable | Adjusted model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ß(95% CI) | SE | P-value | |

| Sample size | 0.14(-0.24–0.52) | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Publication year | -20.14(-61.7–21.4) | 13.1 | 0.22 |

SE-Standard error, ß-regression coefficient, 95% CI Confidence interval

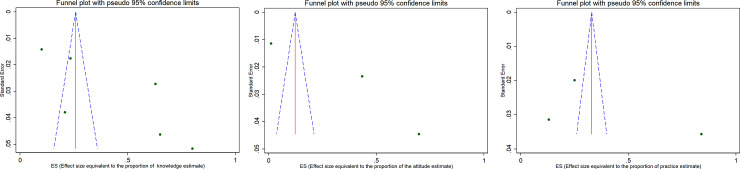

Publication bias

The funnel plot (widely used to examine bias in the result of a meta-analysis) for pooled estimates of knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer screening indicated that there was publication bias. The included studies are scattered out of pseudo 95% confidence limit and the observed bias might be due to small study effect [Fig 5A–5C]. Fig 5A, indicates funnel plot of the 6 estimates of knowledge (k) towards cervical cancer screening available for meta-analysis (SE-Standard error, ES-Effect size: proportion), (b) Funnel plot of the 3 estimates of attitude (A) towards cervical cancer screening available for meta-analysis (SE-Standard error, ES-Effect size: proportion), (c) Funnel plot of the 3 estimates of practice towards cervical cancer screening available for meta-analysis (SE-Standard error, ES-Effect size: proportion).

Fig 5. Publication bias assessment: a) Funnel plot of the 6 estimates of knowledge (k) towards cervical cancer screening available for meta-analysis (SE-Standard error, ES-Effect size: proportion), b) Funnel plot of the 3 estimates of attitude (A) towards cervical cancer screening available for meta-analysis (SE-Standard error, ES-Effect size: proportion), c) Funnel plot of the 3 estimates of practice towards cervical cancer screening available for meta-analysis (SE-Standard error, ES-Effect size: proportion).

In this plot, the blue broken line indicates Pseudo 95% CI, the solid red line indicates pooled estimate of the proportion of knowledge, attitude and practice, and the scattered circle dots indicates included studies in the meta-analysis. The scale on the X-axis indicates Effect size estimate or proportion and the Y-axis indicates the precision estimate using standard Error.

In this plot, the blue broken line indicates Pseudo 95% CI, the solid red line indicates pooled estimate of the proportion of knowledge, attitude and practice, and the scattered circle dots indicates included studies in the meta-analysis. The scale on the X-axis indicates Effect size estimate or proportion and the Y-axis indicates the precision estimate using standard Error.

Discussion

In this review, the pooled estimate of knowledge, attitude and practice of HIV infected women towards cervical cancer screening in Africa was 43.0%, 38.0% and 41.0%, respectively. The highest heterogeneity and publication bias were observed in meta-analysis using forest plot and funnel plot, respectively. The Meta-regression model was applied to identify the reason for heterogeneity using sample size and publication years. However, the variation did not show a significant association on the effect size equivalent to the proportion or the outcome variables.

The knowledge estimate of our finding was concordant with previously reported review findings in Ethiopia among women of reproductive age group (40.37%) [32] while the attitude and practice findings varied and were 58.87% and 14.02%, respectively [32]. Such variations are likely due to the fact that the study population and settings studied were different from our current review focused on HIV positive women in Africa.

Similarly, Kasraeian et al also in their review made in low and middle-income countries indicated that HIV positive women had less knowledge about cervical cancer and were less likely to undergo screening [33].

The original research articles conducted in different Asian countries, including Pakistan illustrated that participants of the study had inadequate knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer [34]. In the same breath, Iraqi participants only 30.3% of employed and 40.0% of the students of the female population had positive attitude towards cervical cancer screening [35]. Similarly, a study conducted in India indicated that 30.2% of respondents had good knowledge and almost one fourth (25.9%) had a favorable attitude towards cervical cancer [9] with an inspiring result of 58.9% documented for female health care providers’ knowledge of cervical cancer screening [10]. Another study adds up, only 36.48% of the participants have good knowledge and of these, 83.78% of them had a positive attitude, though the vast majority (97.29%) had no practice [7] revealing a big gap between attitude and practice. The study conducted in the Eastern China also reported slightly over half (51.9%) of rural women to have high knowledge of whom, 96.0%of them expressed positive attitude and 63.7% were screened for cervical cancer [11]. Another study from Nepal also reported 42.9% of women to have knowledge and more than 85.0% to have had a positive attitude towards cervical screening [12]. Whereas the Iranian study showed more than half (58.0%) of patients with cancer knew that their diseases was malignant [8].

When looked at the African continent, very diverse findings were also reported. According to the Tanzania study, only 10.4% of women were knowledgeable about cervical cancer and 7.9% of these were screened [36] which was very low. Similarly, in Nigeria18.1% of them had good knowledge with 67.8% of them to have a positive attitude to cervical cancer screening [37]. In Uganda and Burkina-Faso, the two studies reported that only 4.8% and 11.1% of women had been screened for cervical cancer, respectively [13, 14]. The various studies done in Ethiopia also showed different results [15–18]. The study done among University female students in Debre-Berhan, North Ethiopia reported 35.6%, while the study in Wolaita, southern Ethiopia among women of reproductive age reported 43.1% to have good knowledge towards cervical cancer showing better results [15, 16]. Of the 43.1% of the women, studied in Wolaita, 45.5% of them had a positive attitude with 22.9% of them to undergo for screening [16]. On the other hand, the study done in Addis Ababa reported 27.7% of women to have adequate knowledge of cervical cancer and 25.0% of these to undergo for cervical cancer screening [17]. The lowest score for knowledge in Ethiopia was documented for Gonder, northern Ethiopia and it was 19.87% underscoring the need for more advocacy work [18].

Such variable findings of the studies in different countries encouraged us to estimate the pooled effect equivalent to the proportion of the finding which is very crucial for program direction on cervical cancer screening and prevention measure aspects.

Strength and limitations of the study

The strength of this review is that we attempted to include the most vulnerable population, women living with HIV in Africa, and has captured the recent publications within ten years till August 2020 and used more than five biomedical databases. The limitation however, is the inclusion of those papers published and reported only in English language which might have missed other important works done in this regard. The precision of the pooling effect might have been also affected by the fact that only very few studies which reported attitude and practice were included and this might consequently affect the assertion.

Conclusion

The pooled estimates of knowledge, attitude and practice of the current review finding was below half in different African countries. The enhancement of knowledge, attitude and practice of women will augment the comprehensive approach to cervical cancer prevention and control strategy. The current work has shed light-on how much the findings of the studies conducted in different countries on the cervical cancer and its screening were very diverse and difficult for decision making. Thus, it is essential to have the pooled estimates of different findings for decision making. Other than this, the pooled estimates are very crucial for further strengthening the strategies for prevention measure and control of cervical cancer mainly on vulnerable population like women infected by HIV.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(DOC)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology, Addis Ababa University, Program of Tropical and Infectious Diseases and Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) for the opportunity to access an internet. The unreserved support rendered by Minilik Demesie from EPHI during the reviewing process of the study protocol was highly appreciable.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- df

degree of freedom

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency virus

- I2

Heterogeneity

- KAP

Knowledge, attitude and practice

- MeSH

Medical subject heading

- tiab

Title and abstract

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.WHO. Cervix uteri, Source: Globocan 2018

- 2.World Health Organization, “UN Joint Global Programme on Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control,” 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.KGaA M., “Global Burden of Cancer in Women,” Int. J. C, vol. 10, pp. 74–75, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.“Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report, Ethiopia", June 2019.

- 5.WHO guidance note: comprehensive cervical cancer prevention and control: a healthier future for girls and women, 2013

- 6.Heena H, Durrani S, AlFayyad I, Riaz M, Tabasim R, Parvez G, et al. , “Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices towards Cervical Cancer and Screening amongst Female Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Journal of Oncology, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varadheswari T, Dandekar RH, and Sharanya T, “A Study on the Prevalence and KAP Regarding Cervical Cancer Among Women Attending a Tertiary Care Hospital in Perambalur,”International Journal of Preventive Medicine Research 2015; Vol. 1, No. 3: pp. 71–78 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eftekhar Z, and Yarandi F, “Knowledge and Concerns about Cancer in Patients with Primary Gynecologic Cancers,” Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2004, Vol 5: pp. 213–216 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brogen Singh Akoijam,et al. “Awareness of cervical cancer and its prevention among women of reproductive age group (15–49 years) in Bishenpur District, Manipur: A cross-sectional study.” IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) 2020; 19(2): pp. 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anantharaman VV, Sudharshini S, Chitra A, “A cross-sectional study on knowledge, attitude, and practice on cervical cancer and screening among female health care providers of Chennai corporation,Journal of Academy of Medical Sciences 2012; 2(4): pp. 124–128 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu T, Li S, Ratcliffe J, and Chen G. “Assessing Knowledge and Attitudes towards Cervical Cancer Screening among Rural Women in Eastern China,”Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 967. 10.3390/ijerph14090967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrestha J, Saha R, Tripathi N. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice regarding Cervical Cancer Screening Amongst Women visiting Tertiary Centre in Kathmandu, Nepal. Nepal Journal of Medical sciences 2013;2(2):85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ndejjo R, Mukama T, Musabyimana A, Musoke D. Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening and Associated Factors among Women in Rural Uganda: A Cross Sectional Study, PLoS ONE 2016; 11(2): e0149696. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawadogo B, Gitta SN, Rutebemberwa E, Sawadogo M, and Meda N. Knowledge and beliefs on cervical cancer and practices on cervical cancer screening among women aged 20 to 50 years in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2012: a cross- sectional study, Pan African Medical Journal 2014; 18:175 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.175.3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mruts KB, and Gebremariam TB, “Knowledge and Perception Towards Cervical Cancer among Female Debre Berhan University Students,” Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2018, 19 (7), 1771–1777 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.7.1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tekle T, Wolka E, Nega B, Kumma WP, and Koyira MM, “Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women and Associated Factors in Hospitals of Wolaita Zone,” Cancer Management and Research 2020:12; pp. 993–1005 10.2147/CMAR.S240364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Getachew S, Getachew E, Gizaw M, Ayele W, Addissie A, Kantelhardt EJ. Cervical cancer screening knowledge and barriers among women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2019;14(5): e0216522. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mengesha A, Messele A, and Beletew B, “Knowledge and attitude towards cervical cancer among reproductive age group women in Gondar town, North West,”BMC Public Health 2020; 20(209) pp. 1–10 10.1186/s12889-020-8229-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.“PRISMA 2009 Checklist Section / topic PRISMA 2009 Checklist,” pp. 1–2, 2009.

- 20.“Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies,”2017, pp. 1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, and Rothstein HR, Introduction to Meta analysis, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, and Altman DG, “Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses,” 2003, pp. 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterne JAC, and Harbord RM, “Funnel plots in meta-analysis,”2004, no. 2, pp. 127–141 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon K, Tamire M, and Kaba M, “Predictors of cervical cancer screening practice among HIV positive women attending adult anti-retroviral treatment clinics in Bishoftu town, Ethiopia: the application of a health belief model,” BMC Cancer (2019) 19:989 10.1186/s12885-019-6171-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiferaw S, Addissie A, Gizaw M, Hirpa S, W. Ayele W, Getachew S, et al., Knowledge about cervical cancer and barriers toward cervical cancer screening among HIV- positive women attending public health centers in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia; Cancer Medicine 2018; 7(3):903–912 10.1002/cam4.1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell SM, Pedersen HN, Stime EE, Sekikubo M, Moses E, Mwesigwa D, et al. , “Self-collection based HPV testing for cervical cancer screening among women living with HIV in Uganda: a descriptive analysis of knowledge, intentions to screen and factors associated with HPV positivity,” BMC Womens. Health, (2017) 17:4 pp. 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuart A, Obiri-yeboah D, Adu-sarkodie Y, Hayfron-benjamin A, Akorsu AD, and Mayaud P, “Knowledge and experience of a cohort of HIV-positive and HIV-negative Ghanaian women after undergoing human papillomavirus and cervical cancer screening,” BMC Women’s Health (2019) 19:123; pp. 1–11 10.1186/s12905-019-0818-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adibe MO, and Aluh DO, “Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Cervical Cancer Amongst HIV-Positive Women Receiving Care in a Tertiary Hospital in Nigeria,” J Canc Educ (2018) 33:1189–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belglaiaa E, Souho T, Badaoui L, et al. Awareness of cervical cancer among women attending an HIV treatment centre: a cross-sectional study from Morocco. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020343. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosser JI, Njoroge B, and Huchko MJ, “Cervical Cancer Screening Knowledge and Behavior among Women Attending an Urban HIV Clinic in Western Kenya,” J Canc Educ (2015) 30:567–572 10.1007/s13187-014-0787-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maree J.E. & Moitse K.A., ‘Exploration of knowledge of cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening amongst HIV- positive women’, Curationis 2014; 37(1), Art.#1209, 7 pages. 10.4102/curationis.v37i1.1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alamneh YM, Alamneh AA, and Shiferaw AA. “Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening and Associated Factors Among Reproductive Aged Women in Ethiopia: A Meta- Analysis and Systematic Review,” pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasraeian M, Hessamia K, Vafaei H, Asadi N, Foroughinia L, Roozmeh S, et al. , “Patients ‘ self-reported factors in fl uencing cervical cancer screening uptake among HIV-positive women in low- and middle-income countries: An integrative review,” Gynecologic Oncology Reports 33 (2020) 100596 10.1016/j.gore.2020.100596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Javaeed A, Shoukat S, Hina S, et al. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Related to Cervical Cancer Among Adult Women in Azad Kashmir: A Hospital-based Cross-sectional Study. Cureus 2019; 11(3): e4234. 10.7759/cureus.4234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alwan AS, Al-Attar WM, Al Mallah N, and Abdulla KN, “Ass sessing the Knowle edge, Attitude e and Practi ices Tow wards Cervica C al Cance er Scree ening Among a Sample of Iraqi Female Populati ion,”Iraqi i Journal of Biotechnology 2017, Vol. 16, No. 2, 38‐47 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moshi FV, Bago M, Ntwenya J, Mpondo B, Kibusi SM. Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening Services and Its Association with Cervical Cancer Awareness and Knowledge Among Women of Reproductive Age in Dodoma, Tanza- nia: A Cross-Sectional Study. East Afr Health Res J. 2019;3(2):105–114. 10.24248/EAHRJ-D-19-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amu EO, Ndugba SC, Olatona FA. Knowledge of Cervical Cancer and Attitude to Cervical Cancer Screening among Women in Somolu Local Government Area, Lagos, Nigeria; Journal of Community Medicine and Primary Health Care. 2019; 31 (1) 76–85. [Google Scholar]