Hypertension affects four in 10 adults over the age of 25 and is the leading risk factor for death and disability globally.1, 2 In 2010, hypertension was estimated to cause 9.4 million deaths, or about 18% of total global deaths, largely from stroke and ischemic heart disease.1, 2, 3 Hypertension prevalence is on the rise, with 1.56 billion people expected to have hypertension by 2025.4 Although hypertension is largely preventable, it is a driving force in the global epidemic of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).

The World Hypertension League (WHL) is an international, nonprofit organization in official relations with the World Health Organization and the International Society of Hypertension (ISH). The objectives of the WHL include partnering with national member organizations to promote the prevention and control of hypertension globally.5 The WHL designed a needs assessment to guide the development of programs for hypertension prevention and control. The survey objectives were to: (1) determine unifying commonalities in the perceived needs of its membership regarding hypertension prevention, treatment, and control; (2) understand some of the differences in the perceived needs of member organizations regarding hypertension prevention, treatment, and control; and (3) formulate the results of the study into recommendations to the WHL on how to more effectively collaborate with member organizations in the prevention, treatment, and control of hypertension.

Methods

The needs assessment was a cross‐sectional survey of national hypertension organizations enrolled as full members and associate members of the WHL from February 2013 to December 2013. Only one full primary membership is allocated per country, with associate memberships available to additional societies within a given country. The primary and associate membership includes 74 national organizations; however, of those members listed, verifiable contact information was limited to 36 societies. The questionnaire surveyed full member societies' interest in developing or enhancing programs for hypertension prevention and control, opportunities for partnership with WHL, and opportunities for collaboration across member societies. The needs assessment also identified major barriers in developing hypertension control programs, data on surveillance, the application of national guidelines, and solicited feedback on WHL's World Hypertension Day (WHD) (Appendix 1).

Analysis of the data involved both quantitative and qualitative descriptive methodology. Statistical analysis included recording the number of societies in the affirmative for each item and/or percentage positive out of all responding societies that are full members of the WHL. Qualitative methods included an interpretive thematic analysis, with each individual survey's descriptive responses coded thematically with comparisons and subsequent revisions across all respondents (inclusive of full and associate members). The barriers to hypertension programs were determined by this method, with an overall ranking of barriers determined by the total number of respondents that referenced a theme. Qualitative descriptive data did not undergo a theoretical analysis given the small sample size.

Results

The WHL received 26 responses out of a total of 36 societies with verifiable contact information between March and December 2013. Of those who declined completing the assessment, one cited lack of time, another their impending retirement for their respective organization, and a third due to civil unrest in their country. An additional society was omitted from quantitative analysis but kept in the qualitative analysis due to their status as an associate member of WHL. This represented a response rate of 64% (23 of 36), although not all societies answered every question in the assessment. The 22 full members included in the quantitative analysis are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

National Hypertension Societies Responding to the World Hypertension League Needs Assessmenta

| 1. Argentina Arterial Hypertension Society |

| 2. National Heart Foundation of Australia |

| 3. Austrian Society of Hypertension |

| 4. Hypertension Committee of the National Heart Foundation of Bangladesh |

| 5. Belgian Hypertension Committee |

| 6. Brazilian Society of Hypertension |

| 7. Bulgarian Hypertension League |

| 8. Hypertension Canada |

| 9. Egyptian Hypertension Society |

| 10. Estonian Society of Hypertension |

| 11. Iranian Heart Foundation |

| 12. Israel Hypertension Society |

| 13. Italian Society of Hypertension |

| 14. Lebanese Hypertension League |

| 15. Pakistan Hypertension League |

| 16. Polish Society of Hypertension |

| 17. Saudi Hypertension Management Society |

| 18. Slovak League Against Hypertension |

| 19. Swedish Society of Hypertension, Stroke, and Vascular Medicine |

| 20. Thai Hypertension Society |

| 21. Turkish Society of Hypertension and Renal |

| 22. American Society of Hypertension |

An additional World Hypertension League associate member, Turkish Association of Hypertension Control, responded and was included in the qualitative analysis only.

Participants included one society from a low‐income country, two from low‐middle–income countries, seven upper‐middle–income countries, and 12 high‐income countries as defined by the World Bank.6

All of the responding 22 societies were interested in developing or enhancing programs for hypertension prevention and control in their country. Twenty organizations responded to questions on the types of interventions they wanted to enhance or develop. The majority (90% or 18 of 20 societies) wanted to focus on national programs with lesser interest in community (13 of 20), regional (12 of 20), or workplace programs (9 of 20). One half were interested in only one or two interventions while the latter half favored implementing three or all four interventions. Overall, 15% of societies were exclusively focused on national programming, while 10% were interested in either community and/or workplace interventions.

The interest of national hypertension organizations in developing or enhancing different components of hypertension programs was surveyed, with 15 of 19 choosing prevention, 17 of 19 screening, and 17 of 19 control. A total of 68% favored a comprehensive approach inclusive of prevention, screening, and control, and 32% were interested in a focused approach involving one or two domains. Interventions being considered or developed were described by 16 societies, with 63% involved in public education campaigns, 44% educating healthcare providers, 36% conducting surveillance, 25% developing or updating guidelines, and 13% engaging in multi‐sector partnerships.

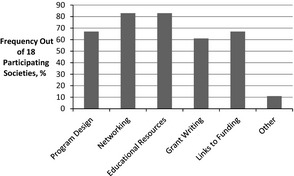

There was a high level of interest (91%) in collaborating with the WHL on programs for hypertension prevention and control. Areas of interest for partnering with WHL are represented in Figure 1. WHL assistance in networking with similar programs from other countries and developing educational resources were both ranked as paramount. Assistance with links to funding bodies and program design were both prioritized second.

Figure 1.

Opportunities for collaboration with the World Hypertension League.

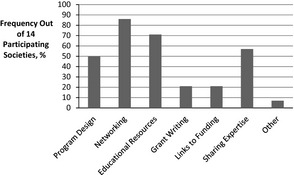

A total of 64% of societies (14 of 22) were interested in collaborating with other countries, with a willingness to share expertise in the domains outlined in Figure 2. The three most highly ranked opportunities for collaboration included networking with similar programs from other countries (12 of 14), development of educational resources (10 of 14), and sharing learning experiences (8 of 14).

Figure 2.

Opportunities for partnership across national hypertension organizations.

Twenty national hypertension organizations identified current interventions in their respective countries and 14 societies included a more detailed description. The majority of interventions (15 of 20) were categorized as national programs (either exclusively focusing on hypertension or a more comprehensive approach inclusive of cardiovascular disease), 8 of 20 societies had community programs, 7 of 20 societies had regional programs, and 6 of 20 societies stated that they had no approach.

With respect to identifying barriers to optimum activities for prevention and control of blood pressure nationally, 91% (20 of 22 societies) responded (Table 2). Lack of resources was the predominant barrier and included a lack of funding sources, healthcare professionals, government support, and research expertise. Problematic healthcare systems were identified as the second major barrier, and included remuneration that overlooked prevention in favor of downstream interventions such as pharmacotherapy or invasive procedures. Other responses in this category included a lack of integrated, national collaborations on NCDs including problems with surveillance and monitoring within clinics (eg, lack of BP measurement devices, professional expertise) and at the policy level (issues of governance and difficulty in evaluating prevention programs). Low health literacy was identified as the third major barrier to optimizing activities for the prevention and control of hypertension, and included social determinants such as poverty.

Table 2.

Barriers to Hypertension Interventions

| 1. Lack of resourcesa |

| 2. Problematic health systemsb |

| 3. Health literacy |

| 4. Unhealthy environmentsc |

| 5. Therapeutic inertiad |

| 6. Adherence |

| 7. Lack of interest among healthcare providers |

aIncludes a lack of funding sources, healthcare professionals, government support, and research expertise. bIncludes a lack of remuneration for preventative strategies and a lack of comprehensive national programs involving surveillance, monitoring, and collaboration. cIncludes problems with the built environment promoting high salt intake, obesity, and sedentary behavior. dRefers to slow application of changes to therapy, including adequate use of combination therapy or not treating at all.

A total of 91%, or 20 of 22 societies, identified having blood pressure surveillance data on their country regarding prevalence, awareness of diagnosis, treatment, and control of hypertension. More than half of respondents utilized unique national guidelines (59% or 13 of 22), 27% (6 of 22) adopted international guidelines, and 14% (3 of 22) employed no guidelines. A need for guidelines better suited to their respective country was identified by 27% (6 of 22). The main reasons for requiring unique guidelines included economic constraints as well as differences in ethnicity and language.

Participants were also asked to prioritize, from their organization's perspective, 10 possible actions the WHL could undertake using a 5‐point scale (1=high priority and 5=low priority). The overall ranking was determined from the greatest number of societies assigning a value of “1” or “2” (Table 3). Developing a network with funding organizations was flagged as the predominant priority by respondents (13 of 19 societies), as well as conducting training sessions for healthcare professionals in hypertension control (13 of 19), training sessions to develop strategic plans for hypertension prevention and control (13 of 20), and training sessions to develop sodium reduction programs (11 of 18).

Table 3.

Prioritization of Potential World Hypertension League Interventions

| 1. Developing a network of commercial and noncommercial funding organizations that are interested in hypertension that your organization could interact with (13/19 societies). |

| 2. Conducting training sessions on how to train healthcare professionals in improving control of hypertension (13/19 societies). |

| 3. Conducting training sessions to develop strategic plans for prevention and control of hypertension (13/20 societies). |

| 4. Conducting training sessions for developing sodium reduction programs (11/18 societies). |

| 5. Assistance in the development of research protocols (11/18 societies). |

| 6. Assistance in development of standardized public education materials that are culturally and linguistically appropriate to your setting (10/19 societies). |

| 7. Assistance in development of standardized healthcare professional materials that are appropriate to the needs of healthcare professionals in your country (9/18 societies). |

| 8. Working with the World Health Organization and other organizations to develop a list of core antihypertensive drugs and advocating for funding for these drugs (9/19 societies). |

| 9. Assistance in development of material for policy makers on the importance of prevention and control of hypertension (8/15a societies). |

| 10. Assistance in developing health economic models for hypertension prevention and control for your country or region (6/18 societies). |

Due to a formatting error, this intervention was not visible on three of the respondents' surveys. Not all respondents ranked every intervention.

WHD was ranked as very useful by 28% (5 of 18 societies), somewhat useful by 28% (5 of 18 societies), neutral by 22% (4 of 18), and not useful by 22% (4 of 18).

Discussion

This needs assessment provides a basis for national hypertension organizations to work together toward reducing the burden of hypertension‐related disease. The majority of the organizations wanted to partner with other national hypertension organizations and the WHL. A high priority for organizations was the development of national programs with multiple dimensions (involving prevention, screening, and control, encompassing public and healthcare professional education). Many organizations were also interested in community, regional, or workplace programs. As expected, a lack of monitory and personnel resources were major barriers faced by organizations, followed by inadequate healthcare systems and low health literacy of the public. Notably, a lack of appropriate hypertension guidelines was indicated by only a quarter of the organizations. Organizations indicated that the WHL could be of assistance by developing a network of potential funding bodies and a network of national organizations working together toward common goals. It was also indicated that there was a need for developing training sessions for healthcare professionals on hypertension and assisting with the development of strategic planning for hypertension prevention and control including assistance with developing advocacy programs for reducing dietary salt. Another key issue was the need to engage national governments in healthcare system reform. The needs assessment is complementary and does not overlap with a survey of national hypertension organizations by the ISH, which focused on the use of guidelines‐based care.7

The needs assessment has substantive limitations. A relatively small number of national hypertension organizations responded, and, thus, the results may not be generalizable to other national hypertension organizations. In particular, there was only one respondent from a low‐income country and two from low‐middle–income countries and hence the survey is less likely to be generalizable to organizations in low‐resource settings. There were no responses from African organizations in the survey. The needs assessment indicates that the WHL must reengage member organizations especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries where the global burden of hypertension is highest. Nevertheless, there was a high response rate from organizations with whom the WHL had confirmed contact information. The survey identified national organizations that wish to collaborate with the WHL and sets an agenda for such collaboration. It is also a potential limitation that the surveys are filled by individuals who may or may not reflect the needs of the organization they represent and/or that the responses may not represent the needs of their countries' populations. In all, the responses indicate many common themes across organizations suggesting that the major observations are valid.

The WHL is currently restructuring and aligning resources to better address its global responsibility and mandate. The United Nations has indicated four critical targets for 2025 that impact hypertension: to reduce the prevalence of hypertension by 25%, to reduce dietary sodium by 30%, to have 80% coverage of essential cardiovascular medications, and to reduce premature mortality from NCDs by 25%.8 These targets are highly integrated, as reducing NCDs is unlikely without a significant reduction in hypertension‐related disease while reducing dietary salt would substantively achieve the target to reduce hypertension prevalence. The WHL has prioritized partnering with national hypertension organizations and has now reestablished contact with 50 organizations and is developing partnerships with international health organizations. The top WHL operational priorities are designed to enhance the effort to reduce dietary salt and increase screening and diagnosis of hypertension population‐wide. Since conducting the needs assessment in 2013, the WHL has developed a policy statement on reducing dietary salt9 and a call for improving the quality of research on dietary salt,10 developed an overview for strategic planning for hypertension prevention and control,5 established The Journal of Clinical Hypertension as its official journal,11 provided policy guidance on selecting automated blood pressure devices,12 developed fact sheets on blood pressure13 and on dietary salt14 to aid advocacy, established recommended nomenclature for describing dietary salt intake and reduction in dietary salt,15 and developed guidelines for analyzing hypertension surveys.16 In addition, working groups will issue a resource on how to develop screening programs for hypertension and cardiovascular risk in low‐resource settings and the WHL has launched a new Web site (www.whleague.org) with a resource center featuring the aforementioned materials. Based on feedback regarding WHD, a rejuvenated effort was made in 2014 to enhance the recognition and impact of this event. WHD 2014 incorporated a global BP screening challenge that was widely embraced by more than 30 nations, achieving three times the screening goal (as summarized in a report posted on the new Web site). The WHL will work with member organizations to adopt these policies, resources, and events as well as create new resources to aid hypertension prevention and control globally.

Conclusions

Hypertension prevention and control remains a major global challenge. National hypertension organizations indicate a strong desire to work together to prevent and control hypertension. Although the needs assessment had substantive limitations, it helps forge an agenda for partnership between WHL and national hypertension organizations. The findings signal the need for the WHL to develop a network of potential funding bodies and networks of national organizations working toward common goals. It also indicated a demand for training sessions for healthcare professionals and a need to assist strategic planning for hypertension prevention. Developing new hypertension guidelines was not ranked highly by the respondents. There is a clear need to develop an expanded multi‐sector network, broaden membership to include more national hypertension organizations, and establish innovative partnerships with corporations and large‐scale provider groups to work towards the League's mandate and United Nations targets.

Statement of Financial Disclosure

Drs Khalsa, Campbell, Lackland, Lisheng, and Zhang report no specific funding in relation to this research and no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr Niebylski is a paid contractor for the WHL but has no other conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

The WHL is grateful for the assistance of Chellam Chellappan, Administrative Secretary for the WHL, as well as the following respondents: Argentina Arterial Hypertension Society; National Heart Foundation of Australia; Austrian Society of Hypertension; Hypertension Committee of the National Heart Foundation of Bangladesh; Belgian Hypertension Committee; Brazilian Society of Hypertension; Bulgarian Hypertension League; Hypertension Canada; Egyptian Hypertension Society; Estonian Society of Hypertension; Iranian Heart Foundation; Israel Hypertension Society; Italian Society of Hypertension; Lebanese Hypertension League; Pakistan Hypertension League; Polish Society of Hypertension; Saudi Hypertension Management Society; Slovak League Against Hypertension; Swedish Society of Hypertension, Stroke, and Vascular Medicine; Thai Hypertension Society; Turkish Association of Hypertension Control; Turkish Society of Hypertension and Renal; and the American Society of Hypertension.

Appendix 1. Needs Assessment Questionnaire

References

- 1. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. GBD Arrow Diagram, Risks. Seattle: The Institute; 2013. http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/gbd/visualizations/gbd-arrow-diagram. Accessed June 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . Causes of Death 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden-disease/cod_2008_sources_methods.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, et al. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell NRC, Niebylski ML, World Hypertension League Executive . Prevention and control of hypertension. Developing a global agenda. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2014;29:324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . Data: Country and Lending Groups. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/news/new-country-classifications. Accessed October 12, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chalmers J, Arima H, Harrap S, et al. Global survey of current practice in management of hypertension as reported by societies affiliated with the International Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1043–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013‐2020, vol. 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. http://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/ed. Accessed May 1, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Campbell NRC, Lackland D, Chockalingam A, et al. The World Hypertension League and International Society of Hypertension call on governments, nongovernmental organizations and the food industry to work to reduce dietary sodium. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:99–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campbell NRC, Appel L, Cappuccio F, et al. A call for quality research on salt intake and health: from the World Hypertension League and supporting organizations. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:469–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weber MA, Campbell NR, Lackland DT. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension has become the official journal of the World Hypertension League. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell NR, Berbari AE, Cloutier L, et al. Policy statement of the World Hypertension League on non‐invasive blood pressure measurement devices and blood pressure measurement in the clinical or community setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:320–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Campbell NR, Niebylski M, Lackland D. High blood pressure: why prevention and control are urgent and important. A 2014 fact sheet from the World Hypertension League and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:551–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Campbell NR, Niebylski M, Lackland D. 2014 dietary salt fact sheet of the World Hypertension League, International Society of Hypertension, Pan American Health Organization technical advisory group on cardiovascular disease prevention through dietary salt reduction, WHO coordinating centre on population centre salt reduction, and world action on salt and health. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014. Sep 29 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Campbell NR, Correa‐Rotter R, Cappuccio F, et al. Proposed nomenclature for salt intake and for reductions in dietary salt. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich); In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gee ME, Campbell NR, Sarrafzadegan N, et al. Standards for the uniform reporting of hypertension in adults using population survey data: recommendations from the World Hypertension League expert committee. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014. Aug 26 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]