Abstract

Purpose

To characterize the prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSD), symptoms, and risk factors among ophthalmologists.

Methods

An online survey was distributed to ophthalmologist members of the Maryland Society of Eye Physicians and Surgeons. The survey consisted of 34 questions on respondent demographics, practice characteristics, pain, and effects of MSD on their practice patterns. Participants were excluded if they were not ophthalmologists or if they had MSD symptoms prior to the start of their ophthalmology career. Demographics and practice patterns were compared for those with or without MSD symptoms using the Welch t test and the Fisher exact test.

Results

The survey was completed by 127 of 250 active members (response rate, 51%). Of the 127, 85 (66%) reported experiencing work-related pain, with an average pain level of 4/10. With regard to mean age, height, weight, years in practice, number of patients seen weekly, and hours worked weekly, there was no difference between respondents reporting pain and those without. Those reporting MSD symptoms spent significantly more time in surgery than those who did not (mean of 7.9 vs 5.3 hours/week [P < 0.01]). Fourteen percent of respondents reported plans to retire early due to their symptoms.

Conclusions

A majority of respondents experienced work-related MSD symptoms, which was associated with time spent in surgery. Modifications to the workplace environment focusing on ergonomics, particularly in the operating room, may benefit ophthalmologists.

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) have been well described across professionals. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), in 2015 the cases of work-related MSD accounted for 31% of all worker injuries that were filed (29.8 cases per 10,000 full-time workers in 2015).1,2 Resultant lost wages and lost productivity from worker-related MSDs were estimated to be between $45 and $54 billion annually.3 Although musculoskeletal (MSK) pain is common across all physicians, up to 90% of surgeons have reported of MSK pain while performing surgical tasks.1 Findings across previous studies in this area suggest that occupations in which there are tasks requiring prolonged contraction, static loading, and awkward repetitive positions lead to an increased occurrence of MSDs, which have been found to be more common in surgical specialties than in medical specialties.4–8

Recent literature has shed light on MSK pain in ophthalmologists and optometrists, whose work includes slit-lamp examination and indirect ophthalmoscopy and, for many ophthalmologists, surgery, all of which may be risk factors for injury. Kitzmann et al9 showed that optometrists and ophthalmologists have statistically higher prevalence of MSK pain compared to their family physician counterparts. An Australian study10 followed 297 optometrists and found that 81.5% reported MSK pain in the previous 7 days. Venkatesh et al11 conducted a national survey of ophthalmologists in India and found 70.5% prevalence of back pain, which was associated with performing lasers and indirect ophthalmoscopy (odds ratio, 3.3) and young age (2.0). In Canada, Diaconita et al12 found statistically higher rates of neck pain (46%) and shoulder pain (28%) in 169 ophthalmology respondents compared with their 121 optometry counterparts. Studies from the United Kingdom, United States, Saudi Arabia, and Iran reported similar results.13–16 Ophthalmologists may be at high risk for developing MSDs attributable to factors associated with work mentioned (slit-lamp examination, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and surgery).

There are also some suggestions that certain subspecialists, such as vitreoretinal surgeons or plastic surgeons, may be prone to MSK disorders because of prolonged postures and repetitive tasks. In a survey of oculoplastic surgeons, 72.5% reported pain and 9.2% reported having stopped performing surgery because of pain or neck injury.17 Shaw et al18 studied the postures of 13 vitreoretinal surgeons and found that the spine was moderately flexed for >75% of the time during indirect examinations and this was statistically higher than that encountered during slit-lamp examinations alone (P < 0.05).

Prior studies have suggested that performing surgery exacerbates pain. The current study investigated whether the risk of experiencing pain on a regular basis is associated with the number of hours of surgery performed. More specifically, we aimed to characterize the prevalence, etiology, and effects of work-related pain in Maryland ophthalmologists as well as differences in MSK symptoms among select ophthalmology subspecialties, with a view to identifying potential MSK risk factors associated with physician characteristics and practice patterns. Prevention and treatment modalities were also reviewed.

Subjects and Methods

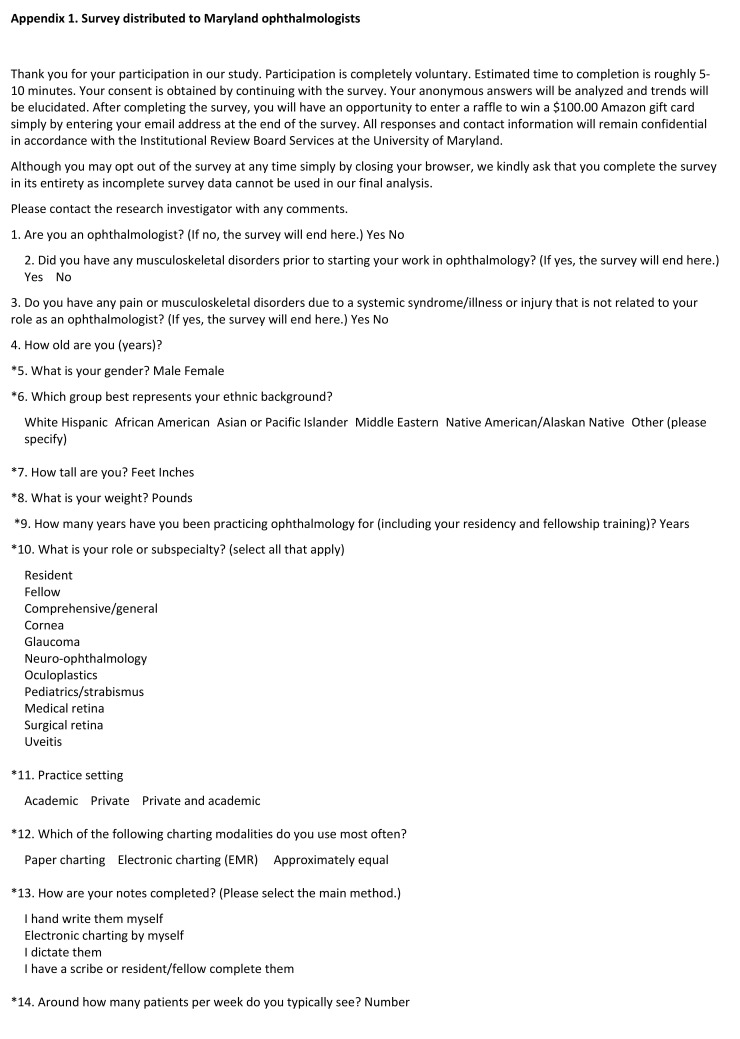

This study was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board prior to the collection of any data. All participants signed an informed consent form. An anonymous, web-based survey was created using SurveyMonkey and distributed to members of the Maryland Society of Eye Physicians and Surgeons, whose membership process is available at http://www.marylandeyemds.org/. See Appendix 1. Participants could opt out of the survey at any time.

Survey

The survey consists of 34 questions. Participants were excluded if they were not ophthalmologists, or if they had musculoskeletal (MSK) pain or a diagnosed MSK disorder prior to their ophthalmology career. Respondents were given the opportunity to add comments throughout the survey.

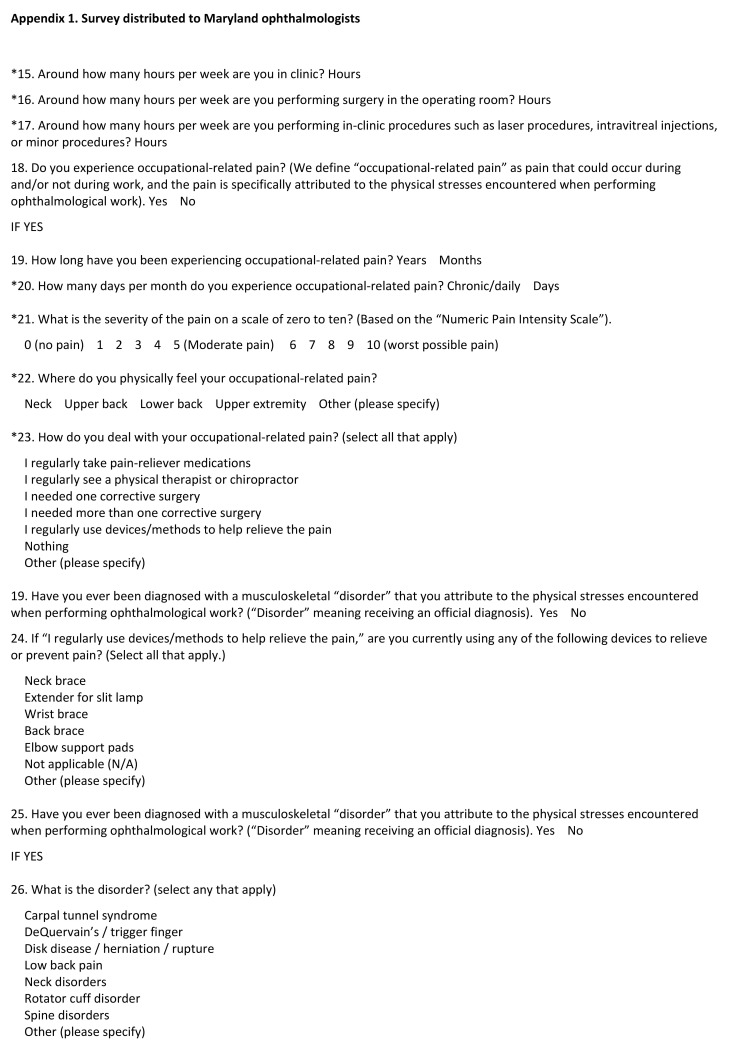

Respondents were asked, “How many days per month do you experience occupational-related pain?” They were also asked to rate pain frequency as either “daily” or to enter the number of days per month. The severity of pain was graded via the validated 10-point Numeric Pain Intensity Scale, because this was accepted as a reproducible method for measuring subjective assessment of pain severity.19 Specific survey questions included age, gender, weight, height, years in practice, general vs subspecialty interest, patient volume, hours per week spent in clinic versus procedure room vs operating room, academic vs private practices, EMR vs paper charting, duration, location and quality of MSK pain, treatment modalities, formal MSK diagnoses (ie, carpal tunnel syndrome, disc disease/herniation, neck/rotator cuff disorders, spine disorders), corrective surgeries, effect of MSK problems on work. Only participants with complete data were included; those with missing data were excluded. Respondents were permitted to add any additional comments. Any narrative comments are reviewed and categorized, if applicable.

Data were analyzed with standard univariate statistical techniques. For attributes described by continuous variables (eg, weight, height, hours in surgery), groups were compared using the Welch t test (http://vassarstats.net/tu.html). For binomial attributes, such as type of practice, the Fisher exact test was used (Matlab, Natick, MA). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

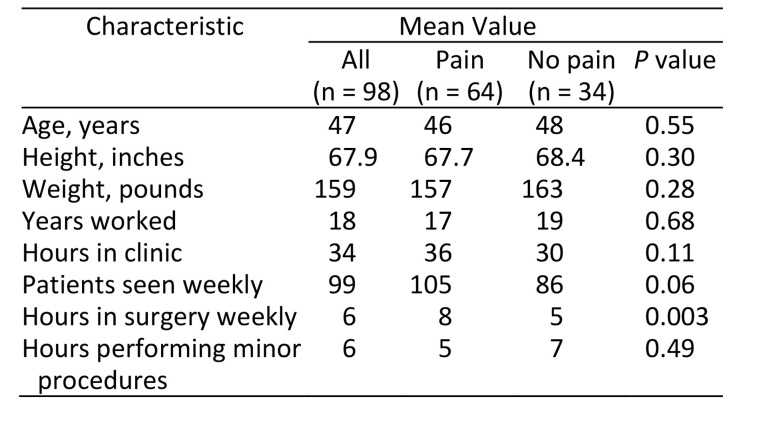

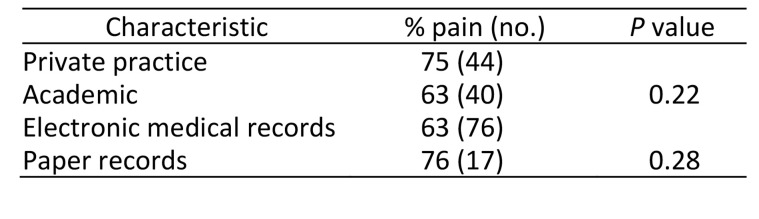

Of the 250 active members surveyed, 127 responded, yielding an overall response rate of 51%. The mean age of respondents was 47 years, with 37% female. We present a summary of the most noteworthy findings collected by the survey. Of the 127 respondents, 85 (66%) reported experiencing occupational-related pain, with an average pain level of 4/10. The respondents experienced pain on average 16.5 days/month, with 30 % experiencing pain daily. Those with and without pain did not differ statistically in terms of demographic data, including age, height, and weight (Table 1). Hours in clinic, number of patients seen, hours performing in-clinic procedures, practice setting (academic vs private), and type of medical record system (EMR vs paper) were not significantly associated with having pain (Table 2). The only significant association was for hours of surgery performed those who reported having pain spent more time performing surgery than those who did not (mean, 7.9 vs 5.3 hours [P < 0.01]).

Table 1.

Respondent demographics

Table 2.

Practice characteristics

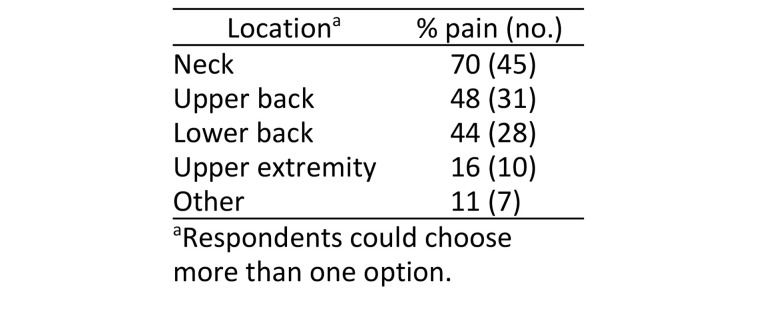

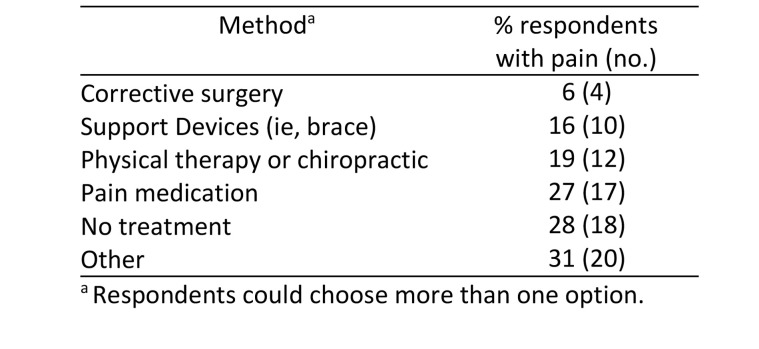

Neck pain was the most common location of pain, reported by 70% of respondents, whereas upper extremity was the least common location (16% [Table 3]). With regard to therapeutic treatments pursued for MSK pain (Table 4), the most common answer was regularly taking oral pain medication (27%). Other treatments listed by the respondents included massage, yoga, and steroid injections.

Table 3.

Location of pain

Table 4.

Treatment methods

Neck pain was the most common location of pain, reported by 70% of respondents, whereas upper extremity was the least common location (16% [Table 3]). With regard to therapeutic treatments pursued for MSK pain (Table 4), the most common answer was regularly taking oral pain medication (27%). Other treatments listed by the respondents included massage, yoga, and steroid injections.

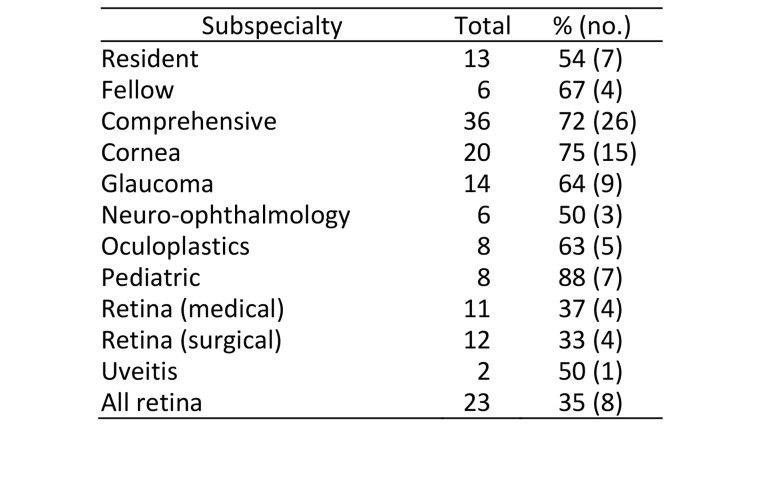

Table 5 gives the prevalence of pain by subspecialty. The prevalence of pain in the highest pain subspecialties (comprehensive, cornea, and pediatric ophthalmology) were significantly higher than the rates for the lowest pain subspecialties (medical and surgical retina). See Table 6. This effect is independent of age.

Table 5.

Distribution of MSK pain by specialty

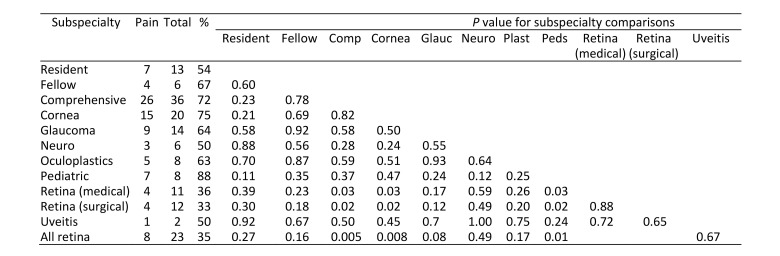

Table 6.

Comparison of pain between different subspecialties

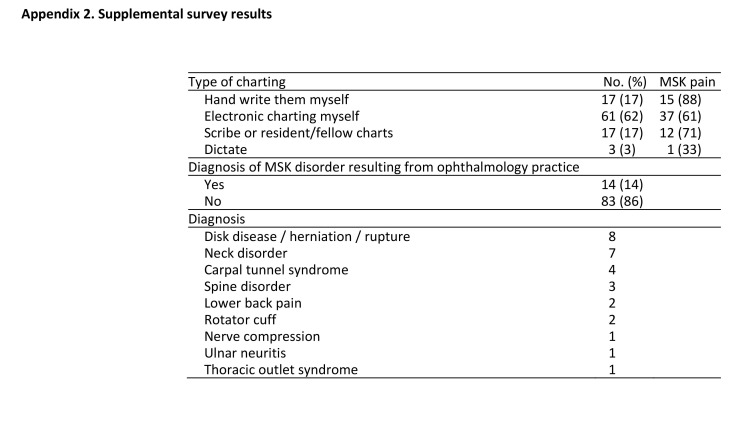

Survey participants were also asked whether work-related pain affected their life and career choices. Of the 127 respondents, 4 (3%) reported that they had reduced operating time and clinic hours; 1 participant had ceased operating entirely. Seventeen respondents (14%) reported an early retirement or plans to retire early, and 2 respondents (2%) reported a change or plan to change their career. Further data are presented in Appendix 2.

Discussion

Two-thirds of ophthalmologists surveyed reported experiencing occupation-related MSK pain, particularly of the neck. Although prior studies have found a high prevalence of MSK pain in eye care providers,9,13 our study found a significant association between those who reported MSK pain and the number of hours they spent performing surgery. We also show a difference among subspecialists independent of age. Additionally, we describe various methods ophthalmologists report using to cope with occupation-related pain and the overall effects of the pain on their careers, including reduced operating time and clinic hours.

The major finding of this study is that those who reported pain spent significantly more time performing surgery than those without pain. Those reporting pain spent on average 3 hours per week longer in surgery than those who did not report pain. Hyer et al16 conducted a national survey assessing back and neck pain among ophthalmologist in UK and found that 33.6% reported pain while operating and that the activity exacerbated the pain. Kitzmann et al9 found that eye care providers had higher prevalence of neck, hand, and lower back pain compared with family medicine physicians.

It is well known that eye surgeons are subjected to many physical demands while operating. Kitzmann et al9 suggested that the repetitive movements, awkward positions, and twisting motions during surgery are likely causative factors. Shaw et al18 suggested that the overall posture of the axial skeleton was just as important as individual neck flexion and lateral bending of the back. Furthermore, they suggested that maximum holding time (MHT), or the maximum time a posture can be held comfortably, is also an important factor. Moderate flexion of lower back was found to have an MHT of 5.6 minutes, for example. For these reasons, the American Academy of Ophthalmology commissioned an ergonomics task force, which recommends operating with neck and back at neutral position, with eyepiece slightly below eye in sitting position.20 Other measures include elbow support and knees bent at 90 degrees. In our survey, there was no association between reported pain and age, height, weight, number of years in practice, number of patients seen per week, or number of hours worked per week. These results are consistent with studies of Indian, UK, and Iranian ophthalmologists and suggest that ergonomic techniques may help clinicians to better manage physical work-related stress.11,15,16

With regard to location of pain, 70% of respondents who had pain reported experiencing neck pain. Upper- and lower-back pain were reported by 48% and 40% of respondents, respectively. These results suggest higher rates of neck pain compared with previous studies of ophthalmologists, in which back pain and neck pain were the most prevalent.13,16,17 A cross-sectional study of Indian ophthalmologists reported that 49% of ophthalmologists experienced lower back pain, whereas 33% experienced neck pain.11 Similarly, Hyer et al reported back pain among 50.6% and neck pain among 31.8% of their study cohort.16

Overall, it appears that increased neck pain is universal among ophthalmologists. Ophthalmologic examinations entail the use of a slit-lamp while seated and indirect ophthalmoscopy while standing, which may result in greater injury to the cervical spine. The use of neck and back braces has been employed by some ophthalmologists to prevent these injuries. Further investigation into the efficacy of these devices is warranted. Repetitive strain encountered during microsurgery, including awkward posture for prolonged periods and limited adjustment of the operating microscope while controlling foot pedals may contribute to increased frequency of pain.

Of respondents with pain, 72% sought treatment, including pain medication (28%), physical therapy (19%), devices (16%), and corrective surgery (6%). The remaining 28% of those with pain did not seek treatment or pain relief. Seventeen (14%) of those with pain reported plans to retire early, and 2 respondents indicated they were considering career changes. These interventions remain similar to what ophthalmologists have reported in prior studies.9,13

Our study found differences in pain scores among respondents representing different ophthalmology subspecialties. Although the sample size was small for individual subspecialties, the effect was large enough to yield significant differences. In particular, our study showed that retina specialists had significantly lower rates of pain than comprehensive, pediatric, or cornea specialists. This was even more pronounced when medical and surgical retina specialists were grouped together. Although hours operating was found to be associated with MSK pain, these subspecialties did not differ significantly in either that variable or in age. Considering the relatively small sample size, the result may be due to self-reporting bias or to particular habits among these groups of doctors, such as how surgical time is scheduled and the types of equipment used. It may also be due to the different demands associated with different subspecialties, because surgical specialties tend to report high risk of neck pain exacerbated by operating, and medical subspecialties are at greatest risk while using the slit-lamp or indirect examinations.

Implications for Working Environment Modification

The significant proportion of ophthalmologists experiencing MSK pain suggests that the need for occupational modifications to minimize pain, improve quality of life, and extend careers is great. In other surgical subspecialties, research has devised strategies and recommendations for improving operating room ergonomics. As a first line of defense, ergonomic working conditions should be emphasized to minimize muscle strain in slit-lamp and operating room microscope. Recent reviews make recommendations for the purchase and set-up of ergonomic equipment in the office and operating room to minimize unnatural postures. For ophthalmologists, these include chairs and tables that can be properly adjusted for slit-lamp examination, microscope eyepieces that can be extended and whose angle can be adjusted, and indirect ophthalmoscopes that are lightweight. The AAO Ergonomics Task Force offers an “Ergonomics Best Practice” course and has recommendations for stretches, improving daily posture, and workplace modifications.20 The recommendations discuss modifications in the operating room, such as placement of arm or wrist rests, can provide support for forearms including instrument design, tilting of the microscope toward surgeon to ensure neutral back position, with back support on the chair. There are also ergonomic devices designed for surgeons, such as back and neck braces and elbow support pads.

Daily schedules can also be modified to minimize the time performing repetitive tasks. Tasks performed in the operating room require greater concentration and involve fewer dynamic movements than those performed in clinic and consequently may be more strenuous to the musculoskeletal system. Operating may also lead to greater pain in those already fatigued by prior repetitive tasks at the slit-lamp biomicroscope. Reducing the total operating or procedure time per day and distributing it more evenly throughout the week may allow for better recovery between cases.

Stress may also play a role in the reported level of pain. In 2005 Dhimitri et al13 demonstrated an association between prevalence of neck and back pain and both female gender and higher stress levels. In contrast, a study of Saudi Arabian ophthalmologists demonstrated no association between mental stress and incidence of neck or back pain.14

Survey studies are subject to self-reporting bias, and this is a potential limitation for the current study. Our response rate was relatively high, and we sought to minimize reporting bias through the use of an anonymous questionnaire. Our sample size in each subspecialty group, however, is relatively small, because we included a diverse population of ophthalmologists including trainees, subspecialists, and both private and academic practitioners. Thus our results have only enough statistical power to detect rather large differences, such as those between retina subspecialists versus pediatric and cornea subspecialists. A lack of significance should not be interpreted to mean no difference in pain prevalence exists between other groups. It may simply be that differences would require a larger sample size to confirm a real effect. While we believe that these findings can be extrapolated in general to the greater ophthalmic community, there may also be bias due to the small geographic area surveyed, in which habits and equipment might be similar among many participants.

This study also did not investigate whether there were gender differences in levels and location of pain reported and whether interventions pursued by males and females differed. Other psychosocial factors, such as the effects of stress levels, hours exercised per week, and ergonomics outside the workplace were not explored. Our study did not explore the effects of gender differences on pain. However, as more women join the ophthalmology workforce, there may be a need to develop gender-specific preventive measures, particularly when considering work-life balance as well as response to chronic pain.21,22 Differences in ergonomics between male and females should also be taken into consideration.23

In conclusion, MSK pain among ophthalmologists is common and its effects on quality of life can be profound. We found a significant association between self-reported musculoskeletal pain and time spent performing surgery. We suggest that greater emphasis be placed on better ergonomic practice habits in the ophthalmic clinics and operating rooms. Ideas to prevent and/or treat musculoskeletal pain include frequent stretch breaks, massages, physical therapy or chiropractic treatments, regular yoga and exercise, and use of back and neck braces and elbow support pads.

References

- 1.Soueid A, Oudit D, Thiagarajah S, Laitung G. The pain of surgery: pain experienced by surgeons while operating. Int J Surg. 2010;8:118–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Bureau of Labor Statistics Nonfatal Occupational Injuries and Illnesses Requiring Days away from Work. News Release. 2016 Nov 10; www.bls.gov/news.release/osh2.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Research Council. the Institute of Medicine. Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace. Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education . Musculoskeletal disorders and the workplace: low back and upper extremities. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Available at http://www.nap.edu/read/10032/chapter/1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan OM, Bayomy H. Occupational respiratory and musculoskeletal symptoms among egyptian female hairdress. J Community Health. 2015;40:670–9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9983-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marx JL, Wertz FD, Dhimitri KC. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmologists. Tech Ophthalmol. 2015;3:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marx JL. Ergonomics: back to the future. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:211–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis WT, Fletcher SA, Guillamondegui OD. Musculoskeletal occupational injury among surgeons: effects for patients, providers, and institutions. J Surg Res. 2014;189:207–12 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morse T, Bruneau H, Dussetschleger J. Musculoskeletal disorders of the neck and shoulder in the dental professions. Work. 2010;35:419–29. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitzmann AS, Fethke NB, Baratz KH, Zimmerman MB, Hackbarth DJ, Gehrs KM. A survey study of musculoskeletal disorders among eye care physicians compared with family medicine physicians. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:213–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long J, Naduvilath TJ, Hao L, et al. Risk factors for physical discomfort in Australian optometrists. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88:317–26. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182045a8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatesh R, Kumar S. Back pain in ophthalmology: national survey of Indian ophthalmologists. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:678–82. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_344_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaconita V, Uhlman K, Mao A, Mather R. Survey of occupational musculoskeletal pain and injury in Canadian ophthalmology. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:314–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhimitri KC, McGwin G, Jr, McNeal SF, et al. Symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmologists. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:179–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Marwani Al-Juhani M, Khandekar R, Al-Harby M, Al-Hassan A, Edward DP. Neck and upper back pain among eye care professionals. Occup Med (Lond) 2015;65:753. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chams H, Mohammadi SF, Moayyeri A. Frequency and assortment of self-report occupational complaints among Iranian ophthalmologists: a preliminary survey. Med Gen Med. 2004;6:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyer JN, Lee RM, Chowdhury HR, Smith HB, Dhital A, Khandwala M. National survey of back & neck pain amongst consultant ophthalmologists in the United Kingdom. Int Ophthalmol. 2015;35:769–75. doi: 10.1007/s10792-015-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivak-Callcott JA, Diaz SR, Ducatman AM, Rosen CL, Nimbarte AD, Sedgeman JA. A survey study of occupational pain and injury in ophthalmic plastic surgeons. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;27:28–32. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181e99cc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw C, Bourkiza R, Wickham L, Mccarthy I, Mckechnie C. Mechanical exposure of ophthalmic surgeons: a quantitative ergonomic evaluation of indirect ophthalmoscopy and slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Can J Ophthalmology. 2017;52:302–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fethke NB, Schall MC, Determan EM, Kitzmann AS. Neck and shoulder muscle activity among ophthalmologists during routine clinical examinations. Int J Ind Ergon. 2015;49:53–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Academy of Ophthalmology, Ergonomics Task Force Ergonomics Best Practices. https://www.aao.org/course/ergonomics-best-practices-course. Accessed January 28, 2020.

- 21.Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:52–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rovner GS, Sunnerhagen KS, Björkdahl A, et al. Chronic pain and sex-differences; women accept and move, while men feel blue. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutton E, Irvin M, Zeigler C, Lee G, Park A. The ergonomics of women in surgery. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1051–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]