Abstract

The effect of fish consumption on blood pressure is controversial. The authors measured blood pressure and calculated oily fish servings per week in 677 community‐dwellers aged 40 years and older living in rural coastal Ecuador. Using regression models with linear splines, the authors evaluated whether dietary fish intake was related to blood pressure levels, after adjusting for relevant confounders. Mean oily fish consumption was 9.1±5.6 servings per week. There was a nonlinear relationship between systolic pressure and fish servings. In the group of individuals consuming up to five servings per week, each serving significantly reduced systolic pressure by 2.3 mm Hg (P=.020). Any extra serving provided no further effects. The study shows an inverse relationship between oily fish consumption and systolic pressure. Currently recommended amounts of dietary oily fish intake per week (1–2 servings) might be insufficient to exert beneficial effects of fish in the control of blood pressure.

Because of the high content of proteins, long‐chain omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω‐3 PUFAs), vitamin D, and other nutrients, oily fish is recommended as a part of a healthy diet.1 In particular, ω‐3 PUFAs have been considered cardioprotectors because of their anti‐inflammatory, antioxidative, antiarrhythmic, and antithrombotic effects.2 These compounds also have blood pressure (BP)–lowering effects, as demonstrated in several studies showing that administration of fish oil capsules is associated with significant reductions in BP levels. According to the information provided by meta‐analyses of controlled trials, this effect is more important in older people and in those with arterial hypertension or hypercholesterolemia.3, 4, 5 Average doses of ω‐3 PUFAs ranged from 3 to 5 g per day in most of the included trials, and the reduction in BP levels varied from 0.5 mm Hg to 5.5 mm Hg according to age and basal BP.

On the other hand, information on the BP‐lowering effect of dietary oily fish intake is controversial, with some studies showing an inverse relationship between fish consumption and BP6, 7, 8, 9, 10 while others disclose no association.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 These contradictory results are most likely related to differences in study design or in the characteristics of participants. A better understanding of the association between dietary fish intake and BP at the population level will lead to more informed decisions on the advice of oily fish consumption by public health authorities. In this population‐based study, we aimed to assess the relationship between wild‐caught oily fish consumption and BP levels in adults living in a coastal Ecuadorian village, where oily fish is a major source of food and energy intake.

Methods

Study Population

Atahualpa (2°18′S #bib80°46′W) is located at sea level, 10 miles west of the Pacific Ocean. The weather is hot and dry, with 12 daily hours of sunlight all during the year. Inhabitants do not migrate, and a sizable proportion of them have never visited large urban centers. More than 95% of the population belongs to the Ecuadorian native/Mestizo ethnic group, and their living characteristics are fairly homogeneous, as detailed elsewhere.16 The diet of villagers is ancestrally rich in fish and carbohydrates but poor in meat and dairy products; there are no fast‐food restaurants in the village and most people eat at home. Because of income restrictions and lack of awareness of their importance, consumption of olive oil, chia seeds, walnuts, flaxseeds, and other food rich in ω‐3 PUFAs––or the use of fish oil supplements––is almost inexistent in the village.

Fish Species Available in Atahualpa

In Atahualpa, fresh wild‐caught fish are acquired at the local market, and the availability of a given species of fish may vary from one day to another. With the exception of a type of white fish, Pacific Moonfish (Selene peruviana), convenient prices make oily fish the preferred fare by Atahualpa residents. Pacific Bumperfish (Chloroscombrus orqueta), Pacific Mackerel (Scomber japonicus), Shortjaw Leatherjacket (Oligoplites refulgens), Pacific Thread Herring (Opisthonema libertate), and sardines (Sardine pilcardus) are the most commonly eaten oily fish species by Atahualpa residents. According to the US Department of Agriculture and the US Department of Health and Human Services (http://www.health.gov/DietaryGuidelines/) and other authoritative reviews,1, 17 these are among the fishes with the highest content of ω‐3 PUFAs (1.3–2.5 g per serving), and, as a result of their relatively small size (15–50 cm), their content of methyl mercury is low (http://www.nrdc.org/health/effects/mercury/guide.asp). These fish are usually served broiled, and it is typical for Atahualpa residents to eat more than one fish on a daily basis.

Study Design

Using a population‐based, cross‐sectional study design, we assessed the relationship between wild‐caught oily fish consumption and BP levels in adults living in Atahualpa. All residents aged 40 years and older were identified during a door‐to‐door survey and invited to participate in this study. Those who signed informed consent were enrolled. The institutional review board of Hospital‐Clínica Kennedy, Guayaquil, Ecuador (FWA 00006867) approved the protocol and the informed consent form.

BP Determinations

BP was measured by trained field personnel with the use of a manual sphygmomanometer (Tycos 7670‐01, Welch Allyn, Skaneateles Falls, NY). Individuals were instructed to avoid food, coffee, and cigarette smoking for at least 1 hour before BP determinations. With the person in the sitting position and after resting for 10 minutes, BP was measured in both arms and the mean value of three readings taken at intervals of 2 minutes (in the arm with the highest reading) was used for analysis.

Covariates Investigated

In addition to age and sex, we considered alcohol intake, physical activity, and body mass index (BMI) for analyses. Alcohol intake was calculated with a questionnaire that inquired about the type and mean number of alcoholic beverages per week and dichotomized in <50 g per day and ≥50 g per day. Physical activity was assessed by self‐report and characterized according to the American Heart Association18 as poor if the person did not perform moderate or vigorous activity. BMI was calculated after obtaining the person's height and weight and categorized as poor if ≥30 kg/m2.19 Smoking was not considered a confounding variable since only 27 (4%) of participants were current or past smokers.

Assessment of Fish Consumption

Participants were asked to quantify their traditional weekly consumption of the different species of oily fish included in a list elaborated by our personnel after visiting the local fish market with the aid of community leaders. In addition, individuals were requested to recall consumption of other fish that might not have been initially listed. Fish were characterized as oily due to its fat content (>5% fat), according to the Food Standards Agency of the UK Government National Archives (http://tna.europarchive.org/20110116113217/http://www.food.gov.uk/news/newsarchive/2004/jun/fishportionslifestagechart). White fish were not considered for this study because of their low content of ω‐3 PUFAs. The number of servings was calculated by dividing the total intake of each fish by the average fish serving size (140 g). For accurate assessment of the amount of ingested fish, our personnel directly weighed edible parts of all oily fish available at the local market before the study. The amount of ingested ω‐3 PUFAs was estimated by multiplying the reported amount of ω‐3 PUFAs per serving for each of the different fish species consumed by each participant. In addition, we estimated the amount of methylmercury content ingested by person.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were carried out using STATA version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics are presented as means±standard deviations for continuous variables and as percentages with 95% confidence intervals for categorical variables. We evaluated the relationship between systolic and diastolic pressures (as dependent variables) and fish servings per week, after adjusting for age, sex, alcohol intake, physical activity, and BMI. The nonlinear relationship between BP and fish servings was evaluated in regression models with linear splines at fixed numbers of servings, according to the slopes found in the regression curve.

Results

A door‐to‐door survey identified 721 Atahualpa residents aged 40 years and older #bib681 (95%) of whom were enrolled. Four individuals were further excluded because of incomplete data collection. The mean age of the 677 participants was 60±12 years; 381 (56%) were women and 128 (19%) reported alcohol ingestion ≥50 g/d. A total of 43 individuals (6%) reported poor physical activity and 177 (26%) had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Mean values for systolic BP were 137±24 mm Hg and for diastolic BP were 77±12 mm Hg, with 237 persons (35%) having BP values ≥140 mm Hg.

Mean oily fish consumption was 9.1±5.6 servings per week (range 0–32), with 223 persons (33%) disclosing up to 5, 379 (56%) from 6 to 15, and 75 (11%) ≥16 servings per week. Table 1 summarizes characteristics of participants and the categories of oily fish servings per week. As observed, there were no differences in mean age, sex, alcohol intake, physical activity, and BMI in the univariate analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Atahualpa Residents Aged 40 Years and Older Across Categories of Oily Fish Servings Per Week

| Total Series (N=677) | 0–5 Servings (n=223) | 6–15 Servings (n=379) | ≥16 Servings (n=75) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD, y | 60 ± 12 | 61 ± 13 | 59 ± 12 | 59 ± 13 | .146 |

| Women, No. (%) | 381 (56) | 127 (57) | 206 (54) | 48 (64) | .297 |

| Alcohol intake ≥50 g/d, No. (%) | 128 (19) | 34 (15) | 81 (21) | 13 (17) | .167 |

| Poor physical activity, No. (%) | 43 (6) | 14 (6) | 25 (7) | 4 (5) | .918 |

| BMI, ≥30 kg/m2, No. (%) | 177 (26) | 58 (26) | 101 (27) | 18 (24) | .891 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Mean estimates of ω‐3 PUFAs intake was 10.6±7.6 g per week, and the mean weekly amounts of methylmercury ingestion was 201±119 ppm. These estimates were based on literature reports of ω‐3 PUFAs and methylmercury content of the different fish species consumed in Atahualpa, as described in the Methods section. The Pearson correlation coefficient showed significant positive relationships between oily fish servings and estimates of grams of ω‐3 PUFAs (R=0.885, P<.0001) and ppm of methylmercury (R=0.783, P<.0001) ingested per week. These were not perfect correlations, ie, R=1, because some fish species have more ω‐3 PUFAs or methylmercury content than others.

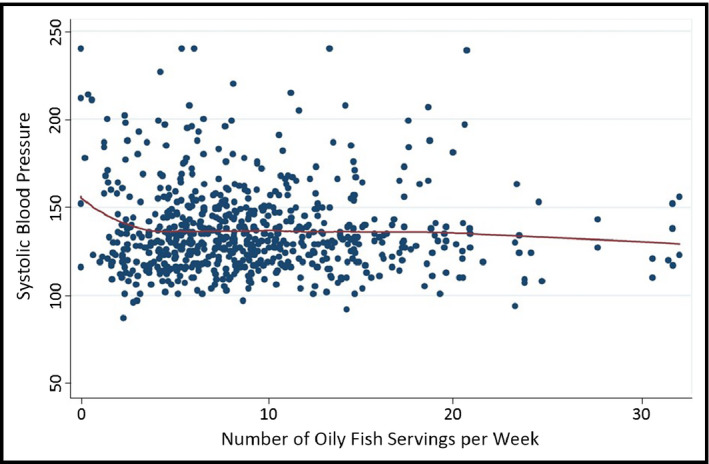

We found a nonlinear relationship between the continuous value of systolic pressure and the number of fish servings per week, after adjusting for age, sex, alcohol intake, physical activity, and BMI (Figure). There was no relationship between fish servings and diastolic pressure. Using regression models with linear splines, we assessed the effect of 0 to 5, 6 to 15, and ≥16 servings per week. In the group of individuals consuming 0 to 5 servings, each serving significantly reduced the systolic pressure (P=.020). This effect was lost in the two other groups (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing of systolic pressure and number of servings of oily fish per week in 677 Atahualpa residents aged 40 years and older.

Table 2.

Inverse Relationship Between Oily Fish Servings Per Week and Systolic Pressure Levelsb

| Oily Fish Servings Per Week | β Coefficienta | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | −2.275 | −4.184 to −0.367 | .020 |

| 6–15 | 0.192 | −0.394 to 0.778 | .520 |

| ≥16 | −0.101 | −0.919 to 0.717 | .809 |

aThe β coefficient (with 95% confidence interval) represents the reduction in mm Hg that each additional serving has on systolic pressure levels. bAfter adjusting for age, sex, alcohol intake, physical activity, and body mass index in regression models with linear splines. The effect was significant in persons consuming up to five servings per week, where a reduction of 2.3 mm Hg of systolic pressure per each additional serving was observed.

Discussion

Bang and colleagues20 suggested that dietary fish intake might be linked to the low prevalence of ischemic heart disease observed in Greenland Eskimos. Since then, several studies have shown an inverse relationship between a diet rich in oily fish and low prevalence rates of cardiovascular events including stroke.21, 22, 23, 24, 25 A lower risk of vascular events in persons adhering to the so‐called Mediterranean diet, which contains fish, has also been reported.26, 27 However, these studies might not be comparable since this diet is also rich in other sources of ω‐3 PUFAs.28 Moreover, many people––at least those living in developed countries––who adhere to a Mediterranean diet also opt for a healthier lifestyle and the results may have been biased even after correcting for confounding variables. In contrast, people living in coastal rural areas of developing countries do not choose to eat fish as a part of a healthier lifestyle but as the most accessible (and likely only) option to get energy from food. This assumption is further supported by the present study, showing no differences in the percentage of heavy alcohol drinkers or those with obesity or poor physical activity across categories of dietary fish intake (Table 1).

The present study, conducted in frequent fish consumers living in a rural Ecuadorian village, shows an inverse relationship between dietary oily fish intake and systolic pressure, after adjusting for potential confounders. This relationship is valid for up to 5 servings per week, where a reduction of 2.3 mm Hg is noticed for each serving. Beyond that, the analysis shows no further modifications in systolic pressure levels as the number of servings increases.

Most studies assessing the relationship between oily fish intake and BP were conducted in small numbers of volunteers who agreed to adhere to a diet rich in farm‐raised oily fish for a few weeks; these samples and scenarios might not be representative of the population at large.6, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15 Community‐based studies addressing the effect of wild‐caught oily fish consumption on BP levels are scarce and present problems inherent to incomplete data collection or inadequate sampling. For example, in the frequently quoted Lugalawa study (Tanzania),7 only 15% of participants were interviewed with a food‐frequency questionnaire to assess the amount of ingested fish, and in another study conducted in the Amazonian jungle, the authors recognized the impossibility to collect an appropriate random sampling of the studied population because of geographical difficulties.14

Pathogenetic mechanisms explaining the BP‐lowering effect of oily fish are complex and include improvement in endothelial function as well as a reduction in heart rate.2 In addition, direct binding and activation of large‐conductance Ca2+‐dependent K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells by one of the ω‐3 PUFAs, docosahexaenoic acid, improve arterial compliance and reduce BP levels.29 Other nutrients present in fish, such as proteins, may also have BP‐lowering effects, as demonstrated in several studies.30, 31 The protein content of oily fish species consumed by Atahualpa residents range from 15 g to 30 g per serving, supposing high amounts of protein intake by enrolled individuals. To what extent fish proteins contributed to the observed effects, however, could not be evaluated. On the other hand, oily fish may contain toxic elements such as methyl‐mercury that may counterbalance the beneficial effects of ω‐3 PUFAs.32, 33 These are the main reasons why studies on the effects of oily fish consumption on BP must not be compared with those evaluating the effect of fish oils given as nutritional supplements.

Study Limitations and Strengths

We did not determine the ω‐3 PUFA concentration in blood and this is a limitation of the present study. In addition, other nutrients (or toxic substances) present in fish were not calculated. Major strengths include the population‐based design with unbiased enrollment and the detailed field instrument used to assess dietary oily fish intake.

Conclusions

The present study provides evidence that oily fish consumption reduces systolic BP. Currently recommended amounts of dietary oily fish intake per week (1–2 servings) might be insufficient to exert this effect as we found a sustained decrease in systolic pressure levels in persons eating up to 5 servings per week. While ≥6 servings per week do not provide additional benefits, there was no association with increased BP levels, suggesting that––at least for the investigated effect––oily fish–related toxicity is irrelevant in individuals who ingest small and medium wild‐caught fish in the South Pacific Ocean.

Funding

Study supported by Universidad Espiritu Santo – Ecuador.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:337–341. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12684 © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Weischselbaum E, Coe S, Buttriss J, Stanner S. Fish in the diet: a review. Nutr Bull. 2013;38:128–177. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mori TA. Omega‐3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology and effects on cardiometabolic risk factors. Food Funct. 2014;5:2004–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morris MC, Sacks F, Rosner B. Does fish oil lower blood pressure? A meta‐analysis of controlled trials. Circulation. 1993;88:523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Appel LJ, Miller ER, Seidler AJ, Whelton PK. Does supplementation of diet with “fish oil” reduce blood pressure? A meta‐analysis of controlled clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1429–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geleijnse JM, Giltay EJ, Grobbee DE, et al. Blood pressure response to fish oil supplementation: metaregression analysis of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1493–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Singer P, Berger I, Luck K, et al. Long‐term effect of mackerel diet on blood pressure, serum lipids and thromboxane formation in patients with mild essential hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 1986;62:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pauletto P, Puato M, Caroli MG, et al. Blood pressure and atherogenic lipoprotein profiles of fish‐diet and vegetarian villagers in Tanzania: the Lugalawa study. Lancet. 1996;348:784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Panagiotakos DB, Zeimbekis A, Boutziouka V, et al. Long‐term fish intake is associated with better lipid profile, arterial blood pressure, and blood glucose levels in elderly people from Mediterranean islands (MEDIS epidemiological study). Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:CR307–CR312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ramel A, Martinez JA, Kiely M, et al. Moderate consumption of fatty fish reduces diastolic blood pressure in overweight and obese European young adults during energy restriction. Nutrition. 2010;26:168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ke L, Ho J, Feng J, et al. Modifiable risk factors including sunlight exposure and fish consumption are associated with risk of hypertension in a large representative population from Macau. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144:152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Houwelingen RV, Nordoy A, van der Beek E, et al. Effect of a moderate fish intake on blood pressure, bleeding time, hematology, and clinical chemistry in healthy males. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;46:424–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cobiac L, Clifton PM, Abbey M, et al. Lipid, lipoprotein, and hemostatic effects of fish vs fish oil n‐3 fatty acid in mildly hyperlipidemic males. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1210–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ness AR, Whitley E, Burr ML, et al. The long‐term effect of advice to eat more fish on blood pressure in men with coronary disease: results from the Diet and Reinfarction Trial. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13:729–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fillion M, Mergler D, Sousa Passos CJS, et al. A preliminary study of mercury exposure and blood pressure in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ Health. 2006;5:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grieger JA, Miller MD, Cobiac L. Investigation of the effects of a high fish diet on inflammatory cytokines, blood pressure, and lipids in healthy older Australians. Food Nutr Res. 2014 Jan 15;58. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v58.20369. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Del Brutto OH, Peñaherrera E, Ochoa E, et al. Door‐to‐door survey of cardiovascular health, stroke, and ischemic heart disease in rural coastal Ecuador – the Atahualpa project: methodology and operational definitions. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mahaffey KR, Sunderland EM, Chan HM, et al. Balancing the benefits of n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and the risks of methylmercury exposure from fish consumption. Nutr Rev. 2011;69:493–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lloyd‐Jones D, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al; American Heart Association strategic planning task force and statistics committee . Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion. The American Heart Association's strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Del Brutto OH, Santamaria M, Ochoa E, et al. Population‐based study of cardiovascular health in Atahualpa, a rural village of coastal Ecuador. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1618–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bang HO, Dyerberg J, Nielsen AB. Plasma lipid and lipoprotein pattern in Greenlandic west‐coast Eskimos. Lancet. 1971;1:1143–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mozaffarian D, Longstreth WT, Lamaitre RN, et al. Fish consumption and stroke risk in elderly individuals. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:200–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vitanen JK, Siscovick DS, Longstreth WT Jr, et al. Fish consumption and risk of subclinical brain abnormalities on MRI in older adults. Neurology. 2008;71:439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holmberg S, Thelin A, Stiernstrom EL. Food choices and coronary heart disease: a population based cohort study in rural Swedish men with 12 years of follow‐up. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:2626–2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Goede J, Geleijnse JM, Boer JM, et al. Marine (n‐3) fatty acids, fish consumption, and the 10‐year risk of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease in a large population of Dutch adults with low fish intake. J Nutr. 2010;140:1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Medrano MJ, Boix R, Palmera A, et al. Towns with extremely low mortality due to ischemic heart disease on Spain. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gardener H, Wright BC, Gu Y, et al. Mediterranean‐style diet and risk of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and vascular diet: the Northern Manhattan Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1458–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoscan Y, Yigit F, Muderrisoglu H. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and its relation with cardiovascular diseases in Turkish population. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:2860–2866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(suppl 6):1402S–1406S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoshi T, Wissuwa B, Tian Y, et al. Omega‐3 fatty acids lower blood pressure by directly activating large‐conductance Ca2+ ‐dependent K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4816–4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rebholz CM, Friedman EE, Powers LJ, et al. Dietary protein intake and blood pressure: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(suppl):S27–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tielemans SM, Alforf‐van der Huil W, Engberink MF, et al. Intake of total protein, plant protein and animal protein in relation to blood pressure: a meta‐analysis of observational and intervention studies. J Hum Hyperetens. 2013;27:564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedersen EB, Jorgensen ME, Pedersen MB, et al. Blood and 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure in Greenlanders and Danes. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith KL, Guentzel JL. Mercury concentrations and omega‐3 fatty acids in fish and shrimp: preferential consumption for maximum health benefits. Mar Pollut Bull. 2010;60:1615–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]