Abstract

The authors aimed to investigate the superiority of angiotensin system blockade (angiotensin‐converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker [ARB]) plus a calcium channel blocker (CCB) (A+C) over other combination therapies in antihypertensive treatment. A meta‐analysis in 20,451 hypertensive patients from eight randomized controlled trials was conducted to compare the A+C treatment with other combination therapies in terms of blood pressure (BP) reduction, clinical outcomes, and adverse events. The results showed that BP reduction did not differ significantly among the A+C therapy and other combination therapies in systolic and diastolic BP (P=.87 and P=.56, respectively). However, A+C therapy, compared with other combination therapies, achieved a significantly lower incidence of cardiovascular composite endpoints, including cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke (risk ratio [RR], 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70–0.91; P<.001), but similar all‐cause mortality (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.77–1.04; P=.15) and stroke rates (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.77–1.04; P=.09). Moreover, A+C therapy yielded a 4.21 mL/min/1.73 m2 lower estimated glomerular filtration rate reduction than other combinations (P<.001). Finally, A+C therapy showed a similar incidence of adverse events as other combination therapies (P=.34) but presented a significantly lower incidence of serious adverse events (RR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73–0.98; P=.03). In conclusion, A+C therapy is superior to other combinations of antihypertensive treatment as it shows a lower incidence of cardiovascular events and adverse events, while it has similar effects in lowering BP and preserving renal function.

In 2002, the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) officers and coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group reported the results of the ALLHAT trial conducted in 33,357 hypertensive patients.1 It was observed that thiazide‐type diuretics achieved a reduction in blood pressure (BP) that was greater by 2 mm Hg compared with the reduction achieved by calcium channel blockers (CCBs) and angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Moreover, thiazide‐type diuretics presented better protection from cardiovascular disease, while their price was lower than that of the other two compared drugs. One year later, the guidelines of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7)2 were released, recommending thiazide‐type diuretics as first‐step therapy in the treatment of hypertension either alone or in combination with other classes of antihypertensive agents. However, at that time, the above recommendations were not endorsed by other international societies of hypertension such as the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). Soon after, diuretic‐based therapy in the treatment of hypertension became popular using mainly the single‐pill combination (SPC) drugs, which were composed of thiazide and ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). These SPC agents also contributed to the improvement of patient adherence to treatment.

In 2008, Jamerson and colleagues3 reported the results of the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living With Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial. ACCOMPLISH was a large randomized multicenter double‐blind trial where 11,506 high‐risk hypertensive individuals received the ACE inhibitor benazepril in combination with the CCB amlodipine or benazepril plus hydrochlorothiazide. ACCOMPLISH demonstrated the benefits of benazepril plus CCB amlodipine in reducing cardiovascular events.3 Currently, according to Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) hypertension guidelines,4 thiazide‐type diuretics are still recommended as first‐line antihypertensive agents together with angiotensin system blockade (ACE inhibitors/ARBs) and CCBs. However, they are not as strongly considered first‐step antihypertensive agents as in JNC 7.

Moreover, in 2011, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines5 did not recommend thiazide diuretics as the drugs of choice for primary hypertension in adults except in cases in which the CCB was intolerable or if there was evidence of heart failure.5 After the ACCOMPLISH study, more SPC tablets with angiotensin system blockade and CCBs became available because of the stronger evidence of cardiovascular protection.

Nevertheless, data regarding the direct comparison between angiotensin system blockade plus CCB (A+C) therapy and other combinations were scarce. We therefore conducted this meta‐analysis to examine the hypothesis that A+C therapy is superior to other combinations in terms of BP lowering and clinical outcomes, including all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), renal function, and adverse events (AEs).

Methods

Literature Search

A literature search was conducted using MEDLINE, Cochrane, and ISI Web of Sciences databases, with no language restrictions until October 2014, using as search terms “angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor [MESH],” or “angiotensin receptor blocker [MESH],” or “calcium channel blocker [MESH],” in combination with the text words “clinical trial.” Data sources were also identified by manually searching through the references of the articles.

Study Eligibility

Studies were deemed eligible if they: (1) were randomized controlled trials with direct comparison between a treatment arm with an ACE inhibitor or ARB combined with a CCB and another treatment arm with another double combination, (2) included at least 200 participants, (3) had more than a 3‐month follow‐up, and (4) reported the incidences of hard endpoints and/or AEs. Studies were excluded if only one agent was used as the basic therapy and another as optional add‐on therapy, as in the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT), in which amlodipine was used as add‐on therapy to perindopril.6 Studies were also excluded for shared populations with other included publications.

Extraction of Data

All data were extracted and checked by two independent authors (CC and YZ) and disagreements were resolved by consensus. For a few studies, authors of those papers were contacted for integral data that were not provided in the published papers. There were not enough data with hazard ratios (HRs), therefore risk ratios (RRs) of hard endpoints were calculated.

Outcomes

Major clinical outcomes included: (1) systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP); (2) mortality and cardiovascular/cerebrovascular outcomes, including all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke; (3) the reservation of renal function, evaluated by the reduction of the estimated glomerular infiltration rate (eGFR), which is accepted as a surrogate for kidney disease progression change instead of biomarkers like proteinuria; and (4) AEs (mild or serious, the latter as predefined in each study).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using review manager software (RevMan Analyses version 5.3.3 Copenhagen; The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). The heterogeneity of included studies was examined by both chi‐square test and I 2 statistics, and when P<.1 or I 2>50%, the heterogeneity was considered statistically significant. Weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) on continuous variables. The random‐effect model was applied throughout this meta‐analysis, regardless of P value and I 2, in order to get a conservative conclusion. P values ≤.05 were considered statistically significant. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the influence of each study on the overall effect by repeating the meta‐analysis while removing one study at a time.

Results

Eligible Clinical Trials

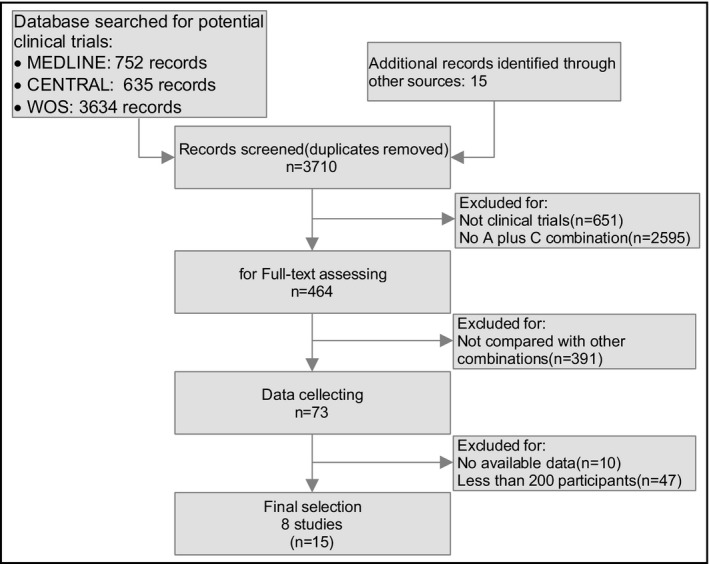

A total of 3710 articles were identified after removing all duplicates, and the number was further narrowed down to 464 after reading headlines and abstracts by two independent investigators (CC and YZ), as shown in Figure 1. There were 73 articles selected for data retrieving, and 391 were excluded for not comparing the A+C therapy with other drug combinations. Finally, 15 articles in eight clinical trials were included in the meta‐analysis,3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 after exclusion of studies with no available data (n=11) or studies with a small sample size (fewer than 200 participants, n=47).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection strategy. A, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; C, calcium channel blocker.

Study Characteristics

A total of 20,451 hypertensive individuals from eight clinical trials were included in this meta‐analysis, the characteristics of which are summarized in the Table. ACE inhibitors or ARBs plus CCBs were taken as the treatment arm in all studies, and there were two antihypertensive strategies with a two‐agent combination as the comparator treatment arm, namely ACE inhibitor or ARB plus diuretics (n=5, A+D therapy) and β‐blocker–based combination therapy (n=3). The population was composed of all types of hypertensives, including general hypertensive individuals from the Japan‐Combined Treatment With Olmesartan and a Calcium Channel Blocker Versus Olmesartan and Diuretics Randomized Efficacy Study (J‐CORE), low‐risk hypertensives from the Combination Therapy of Hypertension to Prevent Cardiovascular Events (COPE) study, elderly hypertensives from the ACCOMPLISH study and the Comparison of Olmesartan Combined With a Calcium Channel Blocker or a Diuretic in Elderly Hypertensive Patients (COLM) study, uncontrolled hypertensives from the EXPLOR study, and hypertensives with type 2 diabetes from the Gauging Albuminuria Reduction With Lotrel in Diabetic Patients With Hypertension (GUARD) study.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Reference, Year | Official Acronym (Sample Size) | Active Drugs | Comparator | Treatment Duration, mo | Characteristics of Participants (Age, y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ogihara, 20147, 8, 9 | COLM (n=5023) | ARB+CCB | ARB+D | >36 | Hypertensives (65–84) with a history of cardiovascular disease |

| Matsuzaki, 201110, 11, 12 | COPE (n=2199) | ARB+CCB | BB+C | 9 | Outpatients (40–85) with hypertension and without obvious CV or metabolic disease |

| Boutouyrie, 201013 | EXPLOR (n=393) | ARB+CCB | BB+C | 1+2+4a | Hypertensives (18–75) resistant to two drugs belonging to two different pharmacologic classes |

| Matsui, 200914, 15, 16 | J‐CORE (n=207) | ARB+CCB | ARB+D | 3+6a | Hypertensives (30–85) |

| Jamerson, 20083, 17 | ACCOMPLISH (n=11506) | ACE inhibitor+CCB | ACE inhibitor+D | 30 | Hypertensives (>55) without obvious CV or metabolic disease |

| Bakris, 200818 | GUARD (n=332) | ACE inhibitor+CCB | ACE inhibitor+D | 12 | Hypertensives (21–85) with type 2 diabetes mellitus and albuminuria |

| Roca‐Cusachs, 200819 | – (n=314) | ACE inhibitor+CCB | ARB+D | 3 | Hypertensives (63.6±8.8) with noninsulin‐dependent type 2 diabetes |

| Holzgreve, 200320 | – (n=450) | ACE inhibitor+CCB | BB+D | 5 | Hypertensives (40–80) with noninsulin‐dependent type 2 diabetes |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, β‐blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; D, diuretic; CV, cardiovascular. aTreatment duration with two‐agent therapy. See text for trial expansions.

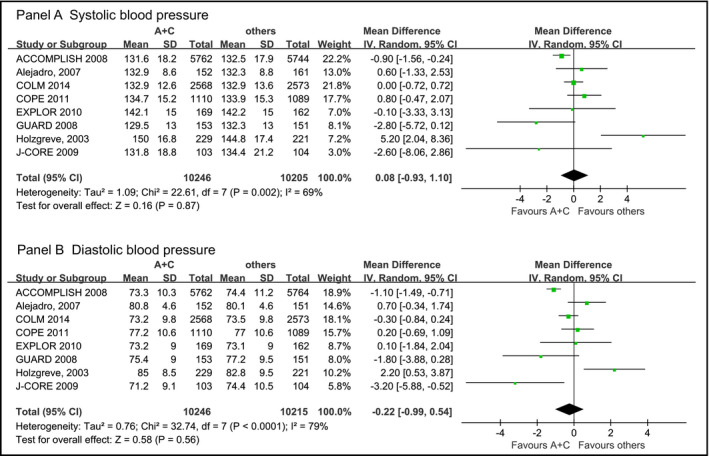

BP Reduction

In Figure 2, BP (SBP and DPB) was compared after treatment among patients receiving A+C therapy and those receiving other combinations. After treatment, SBP did not differ significantly between these two treatment arms, with a WMD of 0.08 (95% CI, −0.93 to 1.10) (P=.87, in panel A). DBP also did not differ significantly between the two treatment arms, with a WMD of −0.22 (95% CI, −0.99 to 0.54) (P=.56, in panel B).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of mean blood pressure (BP) difference between A+C combination therapy and other combinations. Boxes and solid lines indicate mean difference and 95% confidence interval (CI), respectively, for each study. Diamonds and their width indicate the pooled mean difference and the 95% CI, respectively. A indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB); A+C, ACE inhibitor/ARB plus CCB; A+D, ACE inhibitor/ARB plus diuretic; BB, β‐blocker; C, calcium channel blocker; CI, confidence interval; D, diuretic. See text for trial expansions.

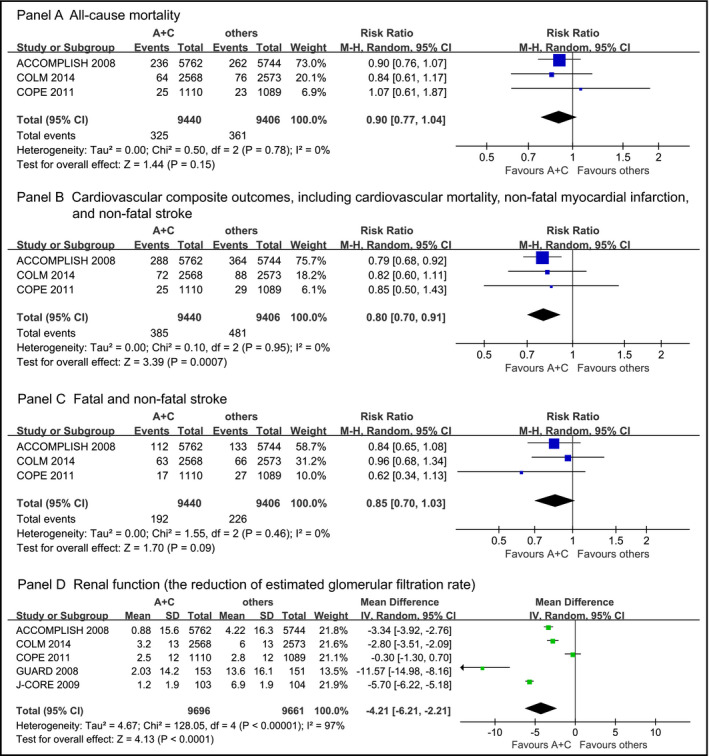

Mortality and Cardiovascular, Cerebrovascular, and Renal Outcomes

As shown in Figure 3, clinical trials were analyzed to compare clinical benefits between A+C therapy and other combinations in terms of all‐cause mortality (panel A), cardiovascular composite outcomes (panel B), fatal and nonfatal stroke (panel C), and renal function, which was assessed by the reduction of eGFR (panel D).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for cardiovascular outcomes and renal function between angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker plus calcium channel blocker (A+C) combination therapy and other therapies (other). Boxes and solid lines indicate mean difference and 95% CI, respectively, for each study. Diamonds and their width indicate the pooled mean difference and the 95% CI, respectively. See text for trial expansions.

Three clinical trials with all‐cause mortality as an endpoint, involving 18,846 hypertensives, were recruited, with similar SBP (P=.74) and DBP reductions (P=.21). In panel A, mortality did not differ significantly between A+C therapy and other combinations, with an RR of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.77–1.04; P=.15). Cardiovascular composite outcomes, including cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke, were also compared between the two treatment arms in patients from these three clinical trials. A+C therapy, however, achieved significantly lower rates of cardiovascular events as compared with other combinations, with an RR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.70–0.91; P<.001). Similar analysis was also conducted on fatal and nonfatal stroke. A+C therapy exhibited a numerically but nonsignificantly lower stroke rate than other combination therapies, with an RR of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.70–1.03) and a marginal P value (P=.09). Five clinical trials with eGFR as an endpoint were recruited for the analysis of renal function. The reduction of eGFR was significantly lower in the A+C group after treatment, as compared with the other combination group, with a WMD of −4.21 (95% CI, −6.21 to −2.21; P<.001).

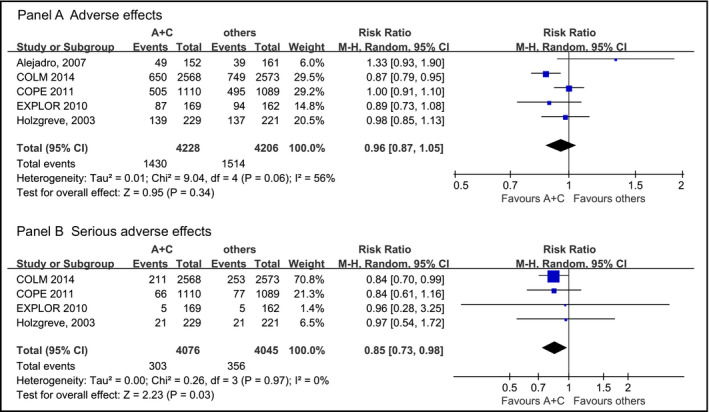

Adverse Events

The definition of AE was not totally the same in each study but included dizziness, peripheral edema, dry cough, and hypokalemia, and were compared between the A+C therapy and other combination therapy groups in 8434 hypertensives from five clinical trials (Figure 4). Discrepancies in AEs between the two treatment arms did not reach statistical significance, with an RR of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.87–1.05) (P=.34, see Figure 4, panel A). Nevertheless, when serious AEs were compared between the two treatment arms, including arrhythmia, malignancy, and renal dysfunction, A+C therapy was associated with a significantly lower incidence of serious AEs than other combinations, with an RR of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.73– 0.98; P=.03) (Figure 4, panel B).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs between angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker plus calcium channel blocker (A+C) combination therapy and other therapies (other). Boxes and solid lines indicate mean difference and 95% CI, respectively, for each study. Diamonds and their width indicate the pooled mean difference and the 95% CI, respectively. See text for trial expansions.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the influence of each study on the overall effect, and most of our findings remained unaltered, including the effect on BP reduction, all‐cause mortality, stroke, renal function, and AEs. However, the pooled risk ratios of cardiovascular composite outcomes and serious AEs became insignificant after removing the ACCOMPLISH trial and COLM trial, respectively. Lack of large random controlled trials may explain these results.

Publication Bias

Heterogeneity existed in some analyses concerning BP reduction, renal function, and AEs (I 2≥56%, P≤.06), whereas most positive findings in the analyses on all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular composite outcomes, fatal and nonfatal stroke, and serious AEs were of great homogeneity (I 2=0% for all analyses, P≥.46).

Discussion

The present meta‐analysis indicates that, for the achievement of the same brachial BP reduction, hypertensive individuals may obtain greater clinical benefits from A+C therapy than from other combinations. A+C therapy achieved a lower incidence of hard cardiovascular endpoints, showed better renal function, and caused fewer serious AEs, as compared with other drug combinations.

Angiotensin system blockade proved to be effective in both cardiovascular protection and target organ damage prevention. In a recent meta‐analysis involving 158,998 hypertensive patients, van Vark and colleagues21 reported that ACE inhibitors were associated with a significant 10% reduction in all‐cause mortality (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.84–0.97; P=.004). Apart from preventing cardiovascular hard endpoints, angiotensin system blockade was also reported to reduce the progress of nephropathy independently from their BP‐lowering effect. For instance, in 2001, a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine by Lewis and colleagues22 indicated that in 1715 patients with nephropathy, the risk of a doubling of the serum creatinine concentration was 37% (P<.001) lower in patients receiving irbesartan compared with patients treated with amlodipine. This trial is considered a landmark in the administration of ARBs as first‐line agents in the treatment of hypertensive nephropathy. More studies on angiotensin system blockade and nephropathy were later published and the protective renal effects of angiotensin system blockade were repeatedly proved.

CCBs, another popular group of antihypertensive agent with emerging evidence of its multiple benefits in hypertensive patients, have been reported to prevent asymptomatic organ damage, in addition to their BP‐lowering effect. Moreover, in 2010, Webb and colleagues23 conducted a meta‐analysis reporting that CCBs were the most effective drugs in reducing BP variability, partly interpreting the superiority of CCBs for the prevention of stroke in patients.

Since ACE inhibitors/ARBs and CCBs were all beneficial for hypertensive patients, especially in cardiovascular/cerebrovascular and renal protection, their combination, if necessary, seems to be a good choice for such patients. This interference was confirmed with randomized controlled trials. In 2013, Kim‐Mitsuyama and colleagues24 reported that in 1164 Japanese hypertensive patients from the Olmesartan and Calcium Antagonists Randomized (OSCAR) study, patients significantly benefited more from A+C therapy than from a high single dose of ARB, with better BP control and lower occurrence of cardiovascular events and heart failure.

On the other hand, thiazide diuretics, as first‐line antihypertensive agents in JNC 8, in combination with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and CCBs, proved to be efficient in hypertension treatment. Based on the results of the ALLHAT study, diuretics were consistently and strongly recommended in African Americans, as they demonstrate great advantages in BP control and cardiovascular protection in this population. In addition, according to the ACCOMPLISH trial, A+D therapy seemed to be more efficient in reducing the urinary albumin creatinine ratio (UACR) than A+C therapy, with a 27.6% reduction of UACR in the A+D group but a 2.9% increment of UACR in the A+C group, which was inverse with the change of eGFR in patients with chronic kidney disease.14 Recently, a meta‐analysis by Olde Engberink25 indicated that thiazide‐like diuretics such as indapamide, compared with thiazide diuretics such as hydrochlorothiazide, provided superior cardiovascular protection with a similar BP‐lowering effect. In combination therapy, however, it remains unknown whether the effect of thiazide‐like diuretics was consistently better than that of thiazide‐type diuretics or even other antihypertensive combination therapies because of the lack of clinical evidence.

It seems that the different combinations of antihypertensive treatments were all beneficial for hypertensive patients, but sparse clinical trials to date leave uncertainty about their superiority in terms of cardiovascular protection and death prevention. Our meta‐analysis confirmed the findings of the ACCOMPLISH study, supporting that A+C therapy should be applied in more hypertensive patients who need combination therapies, in terms of cardiovascular and renal protection. Although the benefit of A+C therapy on cardiovascular protection may need further discussion, the protection of renal function with A+C therapy seems reliable. In 2012, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes BP working group stated that T‐type calcium channels are present in the glomerular afferent and efferent arterioles, and the inhibition of these channels reduces BP within the glomeruli, leading to suppression of urinary albumin excretion.26 In this case, given the well‐known role of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in renal protection, the A+C therapy could be superior through the combined beneficial effects of both agents. Besides, according to a review published by Yasuhiko in 2013,27 CCBs are believed to cause less serious AEs than other antihypertensive agents, which is in agreement with our findings concerning A+C therapy.

According to the evidence from the ALLHAT study and the recommendations from the JNC 7, the diuretic‐based SPC drugs became dominant in the market. In recent years, growing evidence from the ACCOMPLISH study and recommendations from JNC 8 and ESH 2013 suggested that A+C therapy is superior to the former diuretic‐based combinations in terms of cerebral and cardiac protection. Furthermore, in our meta‐analysis, we found that A+C therapy is superior to other combinations, because of its greater cardiovascular protection, renal function reservation, and lower incidence of serious AEs. It can be expected that, in the near future, there will be more emerging A+C SPC drugs on the market and this combination may become dominant.

Study Limitations

The present study needs to be interpreted within the context of its limitations. First, in this meta‐analysis, we included only clinical trials that compared two‐agent combinations, therefore some large clinical trials including only a portion of participants receiving two‐agent combination (leaving others receiving only one agent) were excluded from the present analysis, such as the ASCOT, NORDIL, and INVEST trials. The strict inclusion criteria of this meta‐analysis can be considered as a shortage or the inverse. Second, because of the sparse data in studies with direct comparison, our pooled data were composed of various patients, and we cannot conduct subgroup analysis in different populations, such as in elderly hypertensive or low‐risk hypertensive patients. For the same reason, heterogeneity and publication bias exist in part of our analysis. In order to minimize these effects, a random‐effect model was performed throughout this meta‐analysis. Third, it should be noted that the ACCOMPLISH study contributed more than 50% of the participants in this meta‐analysis. Although it was weighted by the random‐effect model, the dominance of the ACCOMPLISH study should not be ignored. Finally, as a meta‐analysis, its application to clinical practice should be considered with caution. For example, this meta‐analysis included only eight trails, and the treatment time of some of them were not long enough. Moreover, the publication bias cannot be dismissed.

Conclusions

A+C therapy, compared with other dual combination therapies, presented similar BP reductions and achieved greater clinical benefits in cardiovascular outcomes and reservation of renal function. More clinical trials with direct comparison are warranted to verify our findings.

Conflict of interest

None.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:801–808. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12771. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group, The Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial . Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McManus RJ, Caulfield M, Williams B, et al. NICE hypertension guideline 2011: evidence based evolution. BMJ. 2012;344:e181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower‐than‐average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial–Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT‐LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1149–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, et al. Combinations of olmesartan and a calcium channel blocker or a diuretic in elderly hypertensive patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2014;32:2054–2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saruta T, Ogihara T, Saito I, et al. Comparison of olmesartan combined with a calcium channel blocker or a diuretic in elderly hypertensive patients (COLM Study): safety and tolerability. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, et al. Combination therapy of hypertension in the elderly: a subgroup analysis of the Combination of OLMesartan and a calcium channel blocker or diuretic in Japanese elderly hypertensive patients trial. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matsuzaki M, Ogihara T, Umemoto S, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with calcium channel blocker‐based combination therapies in patients with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1649–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rakugi H, Ogihara T, Umemoto S, et al. Combination therapy for hypertension in patients with CKD: a subanalysis of the Combination Therapy of Hypertension to Prevent Cardiovascular Events trial. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:947–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogihara T, Matsuzaki M, Umemoto S, et al. Combination therapy for hypertension in the elderly: a sub‐analysis of the Combination Therapy of Hypertension to Prevent Cardiovascular Events (COPE) Trial. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boutouyrie P, Achouba A, Trunet P, Laurent S; EXPLOR Trialist Group . Amlodipine‐valsartan combination decreases central systolic blood pressure more effectively than the amlodipine‐atenolol combination: the EXPLOR study. Hypertension. 2010;55:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsui Y, Eguchi K, O'Rourke MF, et al. Differential effects between a calcium channel blocker and a diuretic when used in combination with angiotensin II receptor blocker on central aortic pressure in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;54:716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsui Y, Eguchi K, Ishikawa J, et al. Urinary albumin excretion during angiotensin II receptor blockade: comparison of combination treatment with a diuretic or a calcium‐channel blocker. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:466–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsui Y, O'Rourke MF, Hoshide S, et al. Combined effect of angiotensin II receptor blocker and either a calcium channel blocker or diuretic on day‐by‐day variability of home blood pressure: the Japan Combined Treatment with Olmesartan and a Calcium‐Channel Blocker Versus Olmesartan and Diuretics Randomized Efficacy Study. Hypertension. 2012;59:1132–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bakris GL, Sarafidis PA, Weir MR, et al. Renal outcomes with different fixed‐dose combination therapies in patients with hypertension at high risk for cardiovascular events (ACCOMPLISH): a prespecified secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1173–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bakris GL, Toto RD, McCullough PA, et al. Effects of different ACE inhibitor combinations on albuminuria: results of the GUARD study. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1303–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roca‐Cusachs A, Schmieder RE, Triposkiadis F, et al. Efficacy of manidipine/delapril versus losartan/hydrochlorothiazide fixed combinations in patients with hypertension and diabetes. J Hypertens. 2008;26:813–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holzgreve H, Nakov R, Beck K, Janka HU. Antihypertensive therapy with verapamil SR plus trandolapril versus atenolol plus chlorthalidone on glycemic control. Am J Hypertens. 2003;1:381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Vark LC, Bertrand M, Akkerhuis KM, et al. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors reduce mortality in hypertension: a meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors involving 158,998 patients. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2088–2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin‐receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Webb AJ, Fischer U, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM. Effects of antihypertensive‐drug class on interindividual variation in blood pressure and risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:906–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ogawa H, Kim‐Mitsuyama S, Matsui K, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blocker‐based therapy in Japanese elderly, high‐risk, hypertensive patients. Am J Med. 2012;125:981–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olde Engberink RH, Frenkel WJ, van den Bogaard B, et al. Effects of thiazide‐type and thiazide‐like diuretics on cardiovascular events and mortality: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Hypertension. 2015;65:1033–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group . KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney inter Suppl. 2012;2:337–414. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yasuhiko T. Renoprotective effects of the L‐/T‐type calcium channel blocker benidipine in patients with hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2013;9:108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]