Abstract

Elevated blood pressure (BP) is a known factor that affects the structure of the left ventricle. The association between left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and BP in normotensive individuals is poorly understood. All individuals who underwent routine echocardiography and BP measurements as aircrew candidates for the Israeli Air Force in the years 2006 to 2012 were identified. Participants with normal values were included. Associations between echocardiographic characteristics and BP were studied. A total of 2386 participants were included. Mean systolic BP was 125.31±11.18 mm Hg and mean diastolic BP was 68.69±9.02 mm Hg. Interventricular septal (IVS) thickness was positively correlated with systolic BP (P<.001, correlation coefficient 0.121) and significantly inversely correlated with heart rate and hematocrit level (P<.001 for both). Men with evidence of IVS or posterior wall thickening on echocardiography, even within the normal range, may require a closer follow‐up of BP.

Elevated blood pressure (BP) is a known factor that affects the structure and function of the left ventricle.1, 2 Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular mortality.3, 4 An association between BP and left ventricular mass (LVM) has been demonstrated in several studies, but these trials involved only hypertensive individuals.1, 5, 6, 7 Lauer and colleagues7 demonstrated that systolic BP (SBP), and to a lesser degree diastolic BP, in hypertensive individuals are independent markers associated with increased LVM. There is little information about the association between LVM and BP in normotensive individuals, and results are conflicting. Harpaz and colleagues8 evaluated a group of healthy individuals and showed that isolated interventricular septum (IVS) hypertrophy, even in the presence of normal LVM, is associated with hypertension. Fagard and colleagues found no association between LVM and BP values in 92 healthy participants,9 whereas Lorber and colleagues10 did find such an association. Both studies evaluated relatively small samples. Our group previously reported an association between IVS thickening and future development of hypertension in a young healthy cohort of 500 Israeli Air Force (IAF) aviators and argued that IVS thickening may not merely be a result of long‐term BP elevation, but may predict the development of systolic hypertension.11 Identification of individuals at risk for the development of LVH based on BP values and echocardiographic parameters is essential.

Anemia is a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease and in a rat model has been found to be associated with LVH and intramyocardial arteriolar thickening12; however, data in humans regarding the association between hematocrit levels, BP, and LVM are not available.

In light of these data, this retrospective cohort study was designed to identify potential correlations between echocardiographic parameters (specifically LVM and IVS), BP, and complete blood cell (CBC) count in young healthy individuals.

Methods

Patients and Data Collection

The study was a retrospective cohort trial based on routine examinations performed in Israeli Air Force (IAF) academy candidates. All candidates undergo routine echocardiography, BP measurement, and CBC. All patients who underwent these three tests in the years 2006 to 2012 were identified and only those with normal values in all three were included in the analysis. Their BP and CBC were identified and correlates were searched between echocardiographic findings, BP, and CBC. Data were collected from the medical records in the IAF Aeromedical Center (AMC) and from the computerized system of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF). The records were anonymized.

Echocardiographic data were collected from the echocardiographic database present at the IAF AMC.

Echocardiographic Studies

All routine echocardiographic studies of aircrew candidates performed at the IAF AMC between January 2006 and December 2012 were reviewed. All echocardiographic studies were obtained with one of three devices (HP 500 Sonos [Palo Alto, CA] or Philips ATL 5000HDI or HD11XE [Amsterdam, the Netherlands]). Second‐generation devices (HP500 Sonos and ATL 5000HDI) were used from 1994 to 2008. A third‐generation device (Philips HD 11 XE) was used from 2008 onward. All studies were performed by one of three experienced sonographers and interpreted by one of two cardiologists specialized in echocardiography. Transthoracic echocardiography included two‐dimensional, M‐mode, and Doppler studies according to standard American Society for Echocardiography guidelines for obtaining images, quantification of chamber dimensions, and assessment of valvular regurgitation.13, 14 All studies performed at the IAF AMC are performed in four windows. The first and second are the left and right parasternal long‐axis views. The third window is the parasternal short‐axis view, and the fourth is the apical four‐chamber view. Measurements were corrected for body surface area (BSA). LVM was estimated as 1.05 {[left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter (mm)+posterior wall thickness (mm)+intraventricular septum (mm)]3 _ [left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter]3}/1000.

BP Measurements

BP was measured twice in the sitting position following 2 minutes of rest using a sphygmomanometer, and the mean of the measurements was recorded. The BP was measured by skilled technicians who were unaware of the echocardiographic findings. BP levels were defined as elevated if either SBP was lower than 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP was higher than 90 mm Hg. Normal BP was considered when both systolic and diastolic BP were lower than 140 mm Hg and 90 mm Hg, respectively.

Complete Blood Cell Count

All routine CBC samples were processed through the Bayer/Siemens Advia 120 instrument (Tarrytown, NY).15

Statistical Analysis

The selection of variables for inclusion in the model was based on clinical judgment made by the researchers and univariate correlations detected. The assumption of normality was tested by evaluation of the distribution of the model residuals. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Ethical Issues and Anonymity

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Corps of the IDF. It was conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation/Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

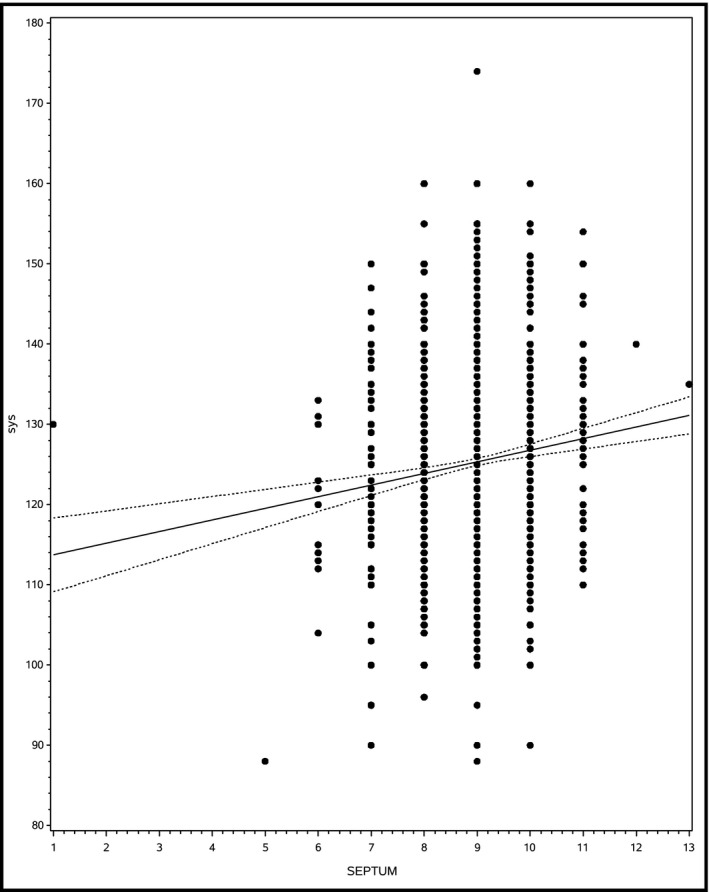

A total of 2386 participants underwent routine BP measurement, echocardiography, and CBC at the IAF AMC from 2006 to 2012 that were interpreted as normal. Demographic and clinical characteristics and echocardiographic measurements are presented in Table 1. All participants were aged 17 to 18 years at the time of the examination and most were men (94%), with a mean hemoglobin level of 14.86±1.11 mg/dL, mean SBP of 125.31±11.18 mm Hg, and a mean diastolic BP of 68.69±9.02 mm Hg. IVS thickness was positively correlated with SBP (P<.001, correlation coefficient 0.121), and significantly inversely correlated with heart rate and hematocrit level (P<.001 for both) (Figure). No significant correlation was found between IVS thickness and diastolic BP or BSA (Table 2). Posterior wall thickness was also significantly positively correlated with SBP, but also with hematocrit levels (P<.001 for both) and significantly inversely correlated with heart rate (P<.001). As with IVS thickness, no significant correlation was found between posterior wall thickness and diastolic BP and BSA (Table 3). In a multivariate linear regression analysis, BSA, systolic and diastolic BP, heart rate, hemoglobin, and hematocrit explained only 3% of the variability in the posterior wall as well as IVS measurements

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristic of 2386 Flight Candidates

| Clinical Parameter | Patients | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 2250 (94) | |

| Body surface area, m2 | 2332 | 2.05±6.08 |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | ||

| Systolic | 2337 | 125.31±11.18 |

| Diastolic | 2334 | 68.69±9.02 |

| Heart rate, beats per min | 2313 | 69.03±17.08 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||

| Left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter, mm | 2384 | 51.32±3.95 |

| Left ventricular end‐systolic diameter, mm | 2385 | 32.16±3.50 |

| Septum, mm | 2385 | 9.02±0.78 |

| Posterior wall, mm | 2384 | 8.77±0.83 |

| Left ventricular mass | 2359 | 165.62±28.02 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 2382 | 33.98±3.83 |

| Aortic root, mm | 2382 | 28.43±2.48 |

| Complete blood cell count parameters | ||

| RBC, M/µL | 2386 | 5.12±0.40 |

| HB, g/dL | 2385 | 14.86±1.11 |

| HCT, % | 2385 | 44.43±3.21 |

Abbreviations: HB, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; RBC, red blood cells. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (percentage).

Figure 1.

Shows the correlation between interventricular septal thickness and systolic blood pressure.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Septum Measurements and Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body surface area | 0.001 | 0.0002–0.002 | .934 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.121 | 0.008–0.001 | <.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | −0.031 | −0.002–0.001 | .158 |

| Heart rate | −0.072 | −0.003–0 | .0006 |

| Hematocrit | −0.070 | −0.016–0.013 | .0006 |

Table 3.

Correlations Between Posterior Wall Measurements and Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body surface area | −0.016 | −0.002–0.002 | .441 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.115 | 0.008–0.001 | <.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | −0.013 | −0.001–0.002 | .549 |

| Heart rate | −0.080 | −0.003–0 | .0001 |

| Hematocrit | 0.131 | 0.033–0.005 | <.0001 |

Discussion

Little has been published about diagnostic approaches that can aid in the prediction of the development of hypertension in normotensive individuals. Measurements of resting heart rate and responses to dynamic exercise have long been known to have some predictive value.16 Additional methods to predict future development of hypertension in healthy individuals with high‐normal BP could be useful and may aid physicians in the identification of those requiring closer surveillance.

Our study evaluated a very large sample of healthy individuals, mostly men. The relatively low BMI of the cohort may serve as evidence for the good general health of these individuals. In addition, because individuals attending the IAF AMC undergo preliminary medical screening, only those without significant medical conditions are evaluated and thus this cohort may be considered in excellent health and without any overt disease. In this population and within the normal range of BP and IVS measurements, a clear association between IVS thickness and SBP, but not diastolic BP, was found (P<.001, correlation coefficient 0.121). Surprisingly, IVS thickness was significantly inversely correlated with heart rate.

These findings suggest that higher IVS and posterior wall values may be caused by higher BP values even within the normal range and such BP values, although considered normal, may help identify individuals at increased risk for future development of LVH. The positive correlation between hematocrit values and posterior wall thickness and LVM stands against this theory, as hematocrit values would be expected to be lower in cases of high plasma volume caused by hemodilution.17 Although the correlation coefficient between SBP and IVS thickness was relatively low, this may have resulted from the low dispersion of IVS thickness values. Additional analysis of this correlation coefficient was performed following omission of the most common value of IVS thickness (9 mm, comprising 64% of the values) and the correlation coefficient between SBP and IVS thickness remained significant and even slightly increased.

Few studies previously studied the association between IVS or LVM and BP in healthy normotensive individuals and results are conflicting. Our group previously reported that in a young healthy population of 500 IAF aviators, followed from initial routine echocardiography at age 20.5±3.3 years at the start of their military service to a mean of 7.5±3.0 years, that IVS thickening was associated with long‐term elevation of SBP, and concluded that IVS thickening may predict the development of systolic hypertension.11 Harpaz and colleagues8 evaluated a small group of 51 apparently healthy pilots with septal hypertrophy (septal thickness >11 mm) defined by routine echocardiography, and showed that IVS hypertrophy, even in the presence of a normal LVM, was associated with hypertension.8 Fagard and colleagues9 found no association between LVM and BP values in 92 healthy individuals, whereas Lorber and colleagues10 did find such an association in a healthy cohort aged 28 to 40 years, and concluded that LVM is associated with SBP and body mass index at BP levels generally considered normal. Both of the latter studies evaluated relatively small samples.

Isolated systolic hypertension in physically active young people has often been argued to be an innocent clinical condition caused by an elevated pulse pressure amplification and low wave arterial reflection from peripheral sites caused by increased arterial elasticity.18 Our results suggest that higher BP values even within the normal range may be associated with increased IVS thickness and thus may not be entirely “innocent.”

Although average SBP was 125 mm Hg, which is currently categorized as prehypertension, and was reported in this cohort, this is not surprising as similar results were reported in similar studies in young air force candidates and may be the result of the stress associated with this demanding screening process.19

Study Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, its retrospective nature did not allow us to collect additional data that may have influenced the results. Second, individuals were evaluated at a single time point, and no follow‐up was performed. We did not perform follow‐up of the individuals evaluated and did not have follow‐up measurements of BP or echocardiographic measurements in the following years. In addition, the population evaluated was highly selected men, thus limiting generalization to mixed populations that include less fit individuals or women. Nevertheless, the large cohort size and the highly selected cohort of healthy individuals makes it possible to reach conclusions regarding the association between echocardiographic parameters, BP, and CBC, previously reported in very small cohorts. Another potential limitation of this study is the fact that the tests were performed by several generations of echocardiographic appliances, and, although during the entire study period all tests were performed by only two technicians and interpreted by three physicians, the different machines may have been responsible for measuring differences during the study period. Another potential limitation is the fact that the participants rested for only 2 minutes before the BP measurement and BP was measured in only one arm in this population. Although significant BP differences between arms in this population have been reported19 and although two minutes of rest may not suffice for the determination of optimal BP, there is no reason to believe that this influenced the correlations presented in this study.

Conclusions

Risk factors for the development of hypertension are numerous. It is often crucial to estimate the risk of future hypertension, especially in normotensive or prehypertensive individuals. Our findings are important, as echocardiographic examination may become an additional tool to predict future hypertension in healthy individuals with BP in the higher limit of normal values. Patients with evidence of IVS or posterior wall thickening on echocardiography, even within the normal range, may require a closer follow‐up of BP compared with those with lower values of IVS or posterior wall thickness. This may prove particularly useful in circumstances where it is crucial to estimate the risk of future hypertension, such as in air crew candidates. Future prospective studies are required to test this association.

Funding

This study was carried out as part of the authors' routine work.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to declare.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:703–706. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12738 © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Gardin JM, Brunner D, Schreiner PJ, et al. Demographics and correlates of five‐year change in echocardiographic left ventricular mass in young black and white adult men and women: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD. Blood pressure, systolic and diastolic, and cardiovascular risks. US population data. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:598–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Casale PN, Devereux RB, Milner M, et al. Value of echocardiographic measurement of left ventricular mass in predicting cardiovascular morbid events in hypertensive men. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, et al. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1561–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balci B, Yilmaz O, Yesildag O. The influence of ambulatory blood pressure profile on left ventricular geometry. Echocardiography. 2004;21:7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bauwens F, Duprez D, De Buyzere M, Clement DL. Blood pressure load determines left ventricular mass in essential hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 1992;34:335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lauer MS, Anderson KM, Levy D. Influence of contemporary versus 30‐year blood pressure levels on left ventricular mass and geometry: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:1287–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harpaz D, Rosenthal T, Peleg E, Shamiss A. The correlation between isolated interventricular septal hypertrophy and 24‐h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in apparently healthy air crew. Blood Press Monit. 2002;7:225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fagard R, Staessen J, Thijs L, Amery A. Relation of left ventricular mass and filling to exercise blood pressure and rest blood pressure. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lorber R, Gidding SS, Daviglus ML, et al. Influence of systolic blood pressure and body mass index on left ventricular structure in healthy African‐American and white young adults: the CARDIA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:955–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grossman C, Grossman A, Koren‐Morag N, et al. Interventricular septum thickness predicts future systolic hypertension in young healthy pilots. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jürgensen JS, Grimm R, Benz K, et al. Effects of anemia and uremia and a combination of both on cardiovascular structures. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2010;33:274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang RM, Bierig M, Deveraux RB, et al; Chamber Quantification Writing Group American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee; European Association of Echocardiography . Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gardin JM, Adams DB, Douglas PS, et al; American Society of Echocardiography . Recommendations for a standardized report for adult transthoracic echocardiography: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Nomenclature and Standards Committee and Task Force for a Standardized Echocardiography Report. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:275–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van den Bossche J, Devreese K, Malfait R, et al. Reference intervals for a complete blood count determined on different automated haematology analysers: Abx Pentra 120 Retic, Coulter Gen‐S, Sysmex SE 9500, Abbott Cell Dyn 4000 and Bayer Advia 120. Clin Chem Lab Med 2002;40:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmieder RE, Messerli FH, Ruddel H. Risks for arterial hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 1986;4:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sawka MN, Convertino VA, Eichner ER, et al. Blood volume: importance and adaptations to exercise training, environmental stresses, and trauma/sickness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Palatini P. Cardiovascular effects of exercise in young hypertensives. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grossman A, Prokupetz A, Gordon B, et al. Inter‐arm blood pressure differences in young, healthy patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15:575–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]