ABSTRACT

The Atg8-family proteins are subdivided into two subfamilies: the GABARAP and LC3 subfamilies. These proteins, which are major players of the autophagy pathway, present a conserved glycine in their C-terminus necessary for their association to the autophagosome membrane. This family of proteins present multiple roles from autophagy induction to autophagosome-lysosome fusion and have been described to play a role during cancer progression. Indeed, GABARAPs are described to be downregulated in cancers, and high expression has been linked to a good prognosis. Regarding LC3 s, their expression does not correlate to a particular tumor type or stage. The involvement of Atg8-family proteins during cancer, therefore, remains unclear, and it appears that their anti-tumor role may be associated with their implication in selective protein degradation by autophagy but might also be independent, in some cases, of their conjugation to autophagosomes. In this review, we will then focus on the involvement of GABARAP and LC3 subfamilies during autophagy and cancer and highlight the similarities but also the differences of action of each subfamily member.

Abbreviations: AIM: Atg8-interacting motif; AMPK: adenosine monophosphate-associated protein kinase; ATG: autophagy-related; BECN1: beclin 1; BIRC6/BRUCE: baculoviral IAP repeat containing 6; BNIP3L/NIX: BCL2 interacting protein 3 like; GABARAP: GABA type A receptor-associated protein; GABARAPL1/2: GABA type A receptor associated protein like 1/2; GABRA/GABAA: gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit; LAP: LC3-associated phagocytosis; LMNB1: lamin B1; MAP1LC3/LC3: microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3; MTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase; PI4K2A/PI4KIIα: phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type 2 alpha; PLEKHM1: plecktrin homology and RUN domain containing M1; PtdIns3K-C1: class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex 1; SQSTM1: sequestosome 1; ULK1: unc51-like autophagy activating kinase 1.

KEYWORDS: Atg8, autophagy, cancer, GABARAP, GABARAPL1, GABARAPL2, LC3

Introduction

Autophagy is a multistep degradation process initiated by the formation of a double-membrane compartment called the phagophore, which sequesters cytoplasmic components, soluble proteins, protein aggregates, or even organelles, and ultimately closes to form an autophagosome (Figure 1). Then, the autophagosome fuses with a lysosome to form an autolysosome, and the content is degraded through the lysosomal hydrolases [1]. Basal autophagy is essential to maintain cellular homeostasis and occurs in every cell, but this process can also be specifically induced by some cell stresses, such as amino acid starvation or hypoxia, in order to maintain cellular energy levels [2]. Even if autophagy was first described as a random degradation process, different types of selective autophagy have since been discovered [3–5]. Deregulation of autophagy is involved in various pathologies, such as cancer where autophagy presents a paradoxical role depending on tumor stage or tumor type. Indeed, it can act as a tumor suppressor mechanism, mainly during the early steps of tumorigenesis by limiting oncogenic stresses, such as DNA damage or oxidative stress, but it can also act as a tumor promotor pathway during the late stages of tumor progression by allowing cancer cell survival under nutrient starvation condition or hypoxia; conditions usually detected in the tumor microenvironment [6]. Therefore, understanding the role and regulation of autophagy proteins is important for the comprehension of cancer progression and, in the future, to develop new anti-cancer therapies targeting the autophagy process in cancers.

Figure 1.

Role of Atg8-family proteins during the autophagy pathway. Top: Molecular mechanism of autophagy. ① Autophagy is induced by cellular stresses (hypoxia, amino acid [AA] starvation …), AMPK activation, and MTOR inactivation leading to ULK1 activation and recruitment to the phagophore. ② LC3s and GABARAPs proteins, previously cleaved by ATG4 proteases, are then conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) or phosphatidylserine (PS) to give the membrane-bound forms of these proteins, LC3s-II and GABARAPs-II. ③ These proteins then play a major role in phagophore elongation and the GABARAPs during closure. ④ The closed autophagosome then re-localizes to the perinuclear space thanks to its interaction with the microtubules ⑤, where it fuses with a lysosome to induce the degradation of its content. ① GABARAPL1 is implicated in MTOR inactivation and AMPK activation, leading to ULK1 activation. ② GABARAP has also been described to be involved in ULK1 activation, while GABARAPL1, like GABARAP, is more efficient in the recruitment of ULK1 to the autophagosome than the LC3s proteins. ③ The PtdIns3K-C1 complex, composed of PIK3C3, ATG14, and other proteins, is recruited to the phagophore through its interaction with Atg8-family proteins, but interacts preferentially with GABARAP and GABARAPL1, inducing the phosphorylation of ATG14 by ULK1 and then the activation of this complex. ER, endoplasmic reticulum. Bottom: Involvement of GABARAPs (GBPs) and LC3B proteins during the early and late stages of autophagy in mammals. ✓, high implication; ✓, low implication; ×, not described to be implicated in mammals

The autophagy pathway requires more than 50 different proteins called autophagy-related (ATG), and some of these are the Atg8 (autophagy-related 8)-family proteins. Atg8-family proteins have all been described to be implicated in many mechanisms such as cellular trafficking, autophagy, and cancer. This family comprises two subfamilies: the GABARAP (GABA type A receptor-associated protein) subfamily composed of 3 members, GABARAP, GABARAPL1 (GABA type A receptor associated protein like 1), and GABARAPL2 (GABA type A receptor associated protein like 2), and the MAP1LC3 (microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3) subfamily, hereafter referred as LC3, composed of 5 members, LC3A with two alternatively spliced isoforms (LC3Aα and LC3Aβ), which differs in their N terminus, LC3B, and LC3B2 with only one different amino-acid from LC3B and LC3C [7–14]. To date, studies on LC3A did not discriminate against the two existing splicing variants. Moreover, only a few studies on LC3B2 exist, and it will not be addressed here. The genes encoding Atg8-family proteins share a high homology at the mRNA level, and similarly for the proteins at the structural level [15]. Indeed, they are all composed of two alpha-helices in their N-terminus, a beta-strand in their C-terminus and a core structure which is similar to the one described in the ubiquitin protein [16,17].

If the role of GABARAPs and LC3s during autophagy were first proposed to be redundant and compensatory, recent studies have highlighted the specificity of each subfamily, and even each subfamily member, in this process. These new data might explain their different behaviors during autophagy and cancer progression.

Roles of Atg8-family proteins during the autophagy process

GABARAP, GABARAPL1, and GABARAPL2 genes are localized on chromosomes 17, 12, and 16, respectively [14] and are coding three different proteins of 117 amino acids, GABARAP, GABARAPL1, and GABARAPL2. Initially, the GABARAPs have been discovered as implicated in intracellular trafficking. Indeed, GABARAP and GABARAPL1 were described to be involved in the transport of the GABRA1/GABAA receptor (gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit 1) [10], the NSF (N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor) [18], and the OPRK1 (opioid receptor kappa 1) [19], while GABARAPL2 was described to be involved in intra-Golgi trafficking [12]. Later, the GABARAPs have then been identified to be involved in autophagy and associated with autophagosomes [20,21].

LC3A, LC3B, LC3B2, and LC3C genes are localized on chromosomes 20, 16, 12, and 1, respectively. These four genes lead to the expression of LC3A, LC3B, LC3B2, and LC3C proteins containing 121, 125, 125, and 147 amino acids, respectively. The LC3s, like the GABARAPs, are involved in the autophagy process [22] and intracellular trafficking. For example, LC3s regulate a specific phagocytosis process called LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP), which induces transmembrane receptor uptake, e.g., TLR (toll like receptors), TRIM4 (tripartite motif containing 4) or CLEC7A/Dectin-1, from the plasma membrane to the lysosome to induce their degradation [23]. The LAP mechanism has been described to be implicated in the antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and, therefore, leads to immune system activation [24]. LAP has only been described for LC3s, and no study, to our knowledge, implicates the involvement of GABARAPs in this process. However, a similar mechanism has been described for the intracellular uptake of the TNFRSF12A/FN14 membrane receptor and its degradation through autophagy via the involvement of GABARAPL2 [25].

The implication of Atg8-family proteins during autophagy is linked to a conserved glycine in their C-terminus, localized at the position 116 for the GABARAPs proteins, position 120 for LC3A and LC3B, and position 136 for LC3C. This glycine is essential for the association of the Atg8-family proteins to the autophagosome membrane (Figure 1). Atg8-family proteins are first cleaved by ATG4 (autophagy related 4 cysteine peptidase) proteases (ATG4A or ATG4B for GABARAP, GABARAPL2, and LC3B; ATG4B, ATG4C, or ATG4D for GABARAPL1) [21,26–29] to give their mature cytosolic forms, referred to for example as LC3-I, etc. Next, these processed proteins are conjugated to a phosphatidylethanolamine/serine to give the phagophore and autophagosome membrane-bound forms, called LC3-II, etc [17,21,30,31]. The lipidated forms of these proteins act as markers of autophagosome formation and number in cells, and LC3B-II proteins are widely used to characterize and quantify the autophagy flux [21]. This conjugation mechanism is reversible for the Atg8-family proteins bound onto the external side of the autophagosome membrane, which can be released in the cytosol following the action of the ATG4 proteases [27], while the ones associated to the internal face of the autophagosome will be degraded with its content [32]. The study of Atg8-family proteins has been initiated in yeast because it expresses only one Atg8, and it has been shown that Atg8 is essential for autophagosome formation [27]. Later, using the homology between yeast and human orthologues, Atg8-family proteins have been studied in other organisms, including humans. Indeed, GABARAPs and LC3s have been both described to be involved in autophagosome assembly [33], elongation [34], membrane curvature [35], autophagosome closure, the fusion between autophagosome and lysosome [31], and for selective autophagy [36,37]. Even if the role of Atg8 family proteins during autophagy appeared to be mainly linked to their presence at the autophagosome membrane, it has also been described that the Atg8-family proteins cytosolic forms of these proteins may also present a role in autophagy. Cellular models expressing the GABARAPG116A or the LC3BG120A mutant, in which the C-terminus glycine 116 or glycine 120 has been replaced by alanine to inhibit their conjugation to the membrane of the autophagosome, have been designed to highlight the role of the cytosolic and membrane-bound Atg8-family proteins [21,38–41].

The first evidence suggesting the implication of Atg8-family proteins in the autophagy pathway came from the establishment of cell lines presenting a knockout of the LC3s, the GABARAPs, or all Atg8-family proteins [42]. During basal autophagy, it appeared that GABARAP proteins might be more important and essential than LC3 proteins. In basal autophagy, each GABARAP contributes to basal autophagy [43] and the overexpression of only one member, GABARAPL1, is sufficient to increase basal autophagy flux independently of its conjugation to autophagosomes [41]. During induced autophagy, the GABARAPs are also preponderant [44], but it appeared that the expression of only one Atg8-family protein is sufficient to ensure induced autophagy flux, except for LC3C [42]. Interestingly, unlike the observation made while studying basal autophagy, overexpression of GABARAPL1 increased induced autophagy, but this effect was dependent on its lipidation [41].

Altogether, these results suggested a main implication of GABARAPs in induced autophagy but the implication of both LC3s and GABARAPs in basal autophagy. These observations may be explained by the potential functional compensatory roles of Atg8-family proteins and by their different roles during each autophagy step.

Role of Atg8-family proteins during the initiation of autophagy

The Atg8-family proteins are initially described to be involved in the late stages of autophagy, such as phagophore closure and fusion with the lysosomes. However, it has been recently shown that they might play a substantial role in the initiation of autophagy as well. The initiation of autophagy consists in the formation of a nascent double-membrane structure, called a phagophore, which then elongates to form a sealed autophagosome (Figure 1). During this step, major molecular complexes need to be recruited to the nascent phagophore. We can cite the ULK1 complex, composed of ULK1/ATG1 (unc51-like autophagy activating kinase 1), RB1CC1/FIP200 (RB1 inducible coiled-coil 1), ATG13 (autophagy related 13), and ATG101 (autophagy related 101) [45]. This complex later recruits the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex 1 (PtdIns3K-C1), composed of BECN1 (beclin 1), ATG14 (autophagy related 14), PIK3C3/VPS34 (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit type 3), PIK3R4/VPS15 (phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 4), and NRBF2 (nuclear receptor binding factor 2) leading to efficient autophagosome formation and maturation [46,47].

First, it has been shown that GABARAPs and LC3s can interact with the ULK1 complex, via their interaction with ULK1, ATG13, and RB1CC1, leading to the recruitment of the complex to the phagophore, but these interactions appeared to be weaker with the LC3 proteins. Moreover, if the LC3s have been described to negatively regulate ULK1 [48], the GABARAPs seems to be essential for ULK1 activation. The role of GABARAPs on ULK1 activation appears to be multiple. First, it has been suggested that GABARAP and GABARAPL1 may activate ULK1 in the cytoplasm at the centriole, and then the complex re-localizes to the growing phagophore [41,49,50]. Then, GABARAPL1 can also activate ULK1 by reducing MTOR activation leading to the decrease of the inhibitory MTOR-mediated phosphorylation of ULK1. Finally, GABARAPL1 may also increase AMPK-induced phosphorylation of ULK1 [41]. The interaction between Atg8 and ULK1 may also prevent excessive autophagy since it has been described in yeast to adjust the autophagy flux to physiological needs [51].

More recently, it has been described that the second initiation complex, PtdIns3K-C1, is recruited to the phagophore through the interaction between GABARAP or GABARAPL1 with ATG14 [52] leading to the ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of ATG14, activation of this complex [53], and, therefore, autophagy.

We may then hypothesize that GABARAP and GABARAPL1 first recruit and activate the ULK1 complex to the phagophore and then recruit the PtdIns3K-C1 through their interaction with ATG14. This interaction then induces the localization of the latter complex in the proximity of the ULK1 complex, therefore, leading to efficient ATG14 phosphorylation by ULK1 and then PtdIns3K-C1 activation.

Role of Atg8-family proteins during the elongation of the phagophore, membrane curvature, and closure

Atg8-family proteins have also been described to be involved in autophagosome membrane elongation, membrane curvature, and autophagosome closure and, therefore, in the regulation of the size of autophagosome (Figure 1). Indeed, low levels of Atg8 leads to a reduction in autophagosome size without affecting autophagosome number in yeast [54], but the implication of the Atg8-family proteins in the membrane curvature and elongation of autophagosomes is still not fully understood. In vitro studies have shown that the lipidation of Atg8-family proteins can induce and stabilize curved membrane structures [35], and Weidberg and collaborators [31] have shown an implication of LC3s in membrane elongation, while GABARAPs were more involved in autophagosome closure in mammals (Figure 1). Indeed, different in vitro studies have shown that GABARAP and GABARAPL2 induce the growth of vesicles leading to spherical structures, while LC3s gave rise to more elongated structures due to the fusion between lipidic vesicles [31,55]. The involvement of Atg8-family proteins and mostly the GABARAPs during the closure of the phagophore involved their interaction with ATG2A and ATG2B. ATG2s are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and facilitate lipid transfer from the ER to the growing phagophore. The interaction between GABARAPs and ATG2s may then be essential for the anchoring of the ATG2s to the growing phagophore [56] (Figure 1). Moreover, Atg8-family proteins may also permit the stabilization of the phagophore by allowing the formation of a meshwork involved in vesicle biogenesis [35,57].

Despite the hypothesis that Atg8-family proteins are involved in autophagosome formation, and that the GABARAPs are also involved in the recruitment and activation of ULK1, and recently, PtdIns3K-C1 complexes in mammals, Atg8-family proteins seems to be dispensable for autophagosome formation. Indeed, in the absence of all Atg8-family proteins in a mammalian cellular model, autophagosomes are fully formed, sealed, and are present in equivalent numbers. However, the autophagosomes are smaller, suggesting that they do not properly elongate, thus, demonstrating the importance of Atg8-family proteins in elongation [42].

Role of Atg8-family proteins during fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes

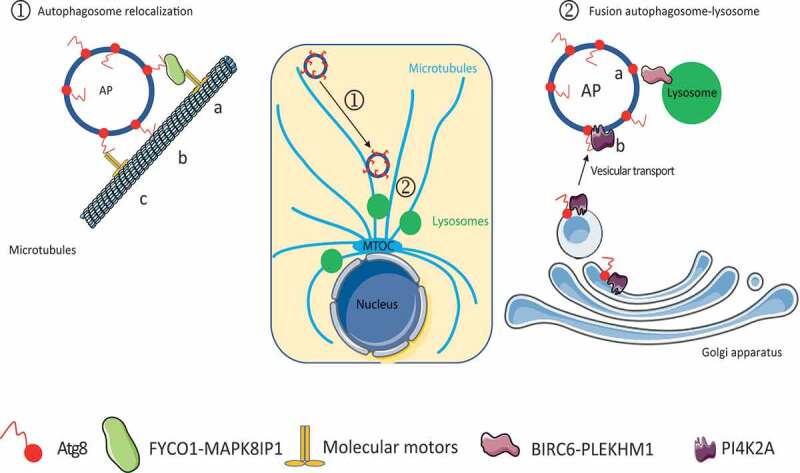

The final stage of autophagy consists of the fusion of the autophagosomes with the lysosome to induce the degradation of their content (Figure 1). The role of Atg8-family proteins during the fusion step (Figure 2) may involve many mechanisms: re-localization and transport of autophagosomes thanks to their MAP (microtubule-associated proteins) properties [58], regulation of the lysosome number, and their acidification and Atg8-family proteins can also act as tethering factors between autophagosome and lysosome [59–63].

Figure 2.

Proposed model describing the role of Atg8-family proteins during the late stages of autophagy. Atg8-family proteins induce ① autophagosome intracellular re-localization through their interaction with FYCO1 or MAPK8IP1 (A), which binds microtubule molecular motors. Atg8-family proteins can also directly bind microtubules (B) or molecular motors, such as dynein (C), to redistribute autophagosomes in cells. Atg8-family proteins also induce ② autophagosome-lysosome fusion through their interaction with PLEKHM1 or BIRC6 (a), two lysosomal proteins, or through PI4K2A recruitment (b) from the Golgi apparatus to facilitate fusion events. AP, autophagosome; MTOC, microtubule-organizing center

Autophagosomes are formed in the peripheral region of cells and must migrate to meet and fuse with lysosomes, mainly localized in the perinuclear portion of the cytoplasm [58], thus, explaining that the Atg8-family proteins implication in autophagosome re-localization regulates the fusion step. During autophagosome re-localization, LC3 proteins seem to be mostly involved. LC3 can interact directly with molecular motors, such as dynein, or indirectly through other proteins, such as FYCO1 (Figure 2) or MAPK8IP1 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 interacting protein 1), to promote autophagosome movement on the microtubules [9,64–68]. GABARAPs are also able to interact with microtubules [69], and we may hypothesize that these proteins might regulate autophagosome transport as well. Then, GABARAPL1 can also regulate the fusion step by increasing the number of lysosomes available in the cells [63].

Atg8-family proteins seem to be necessary for the co-localization of autophagosomes and lysosomes, but it has also been suggested that they are necessary factors for the fusion itself, and it has been shown that GABARAPs are the main protein, which can act as tethering factors to facilitate vesicle fusion (Figure 2). Indeed, the GABARAPs interact with the lysosomal protein PLEKHM1 (plecktrin homology and RUN domain containing M1) and BIRC6/BRUCE (baculoviral IAP repeat containing 6) to establish a bridge between autophagosomes and lysosomes [42,59,60]. Recently, it has also been shown that Atg8-family proteins can regulate the localization of STX16 (syntaxin 16) and STX17 (syntaxin 17), components of the core membrane fusion system composed of SNAREs, and regulate the proper acidification of the lysosome and the fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes [62,70]. GABARAPs can also recruit the Golgi protein PI4K2A (phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type 2 alpha) to the phagophore to generate phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate to activate fusion events [61,71]. Even if the GABARAPs seems to be mostly involved during the fusion step, it appears that in their absence, the LC3 proteins can compensate for their function [43]. Moreover, the LC3B-II proteins can target the protein GORASP2/GRASP55 (golgi reassembly stacking protein 2) to autophagosome upon glucose starvation, where it interacts with LAMP2B (Lysosomal associated membrane protein 2B) to facilitate the fusion between lysosomes and autophagosomes [72].

The involvement of Atg8-family proteins during autophagosome-lysosome fusion has been described to be dependent on their lipidation and, therefore, to their autophagosome localization. Indeed, overexpression of GABARAPL1 led to the activation of fusion steps, whereas overexpression of GABARAPL1G116A had no effect [41]. These results agree with previous observations, which highlighted the necessity of Atg8-family proteins to be localized at the autophagosome membrane. For example, LC3 and GABARAP must be recruited to the autophagosome membrane to play a role in autophagosome movement and the recruitment of fusion factors to the autophagosome membrane (PLEKHM1, BIRC6, PI4K2A), respectively. However, LC3s and GABARAPs may present functional compensatory roles since in vitro studies have described that all Atg8-family proteins can activate fusion events and that the expression of only one of the Atg8-family proteins may be sufficient to induce an efficient fusion.

Role of Atg8-family proteins during selective autophagy

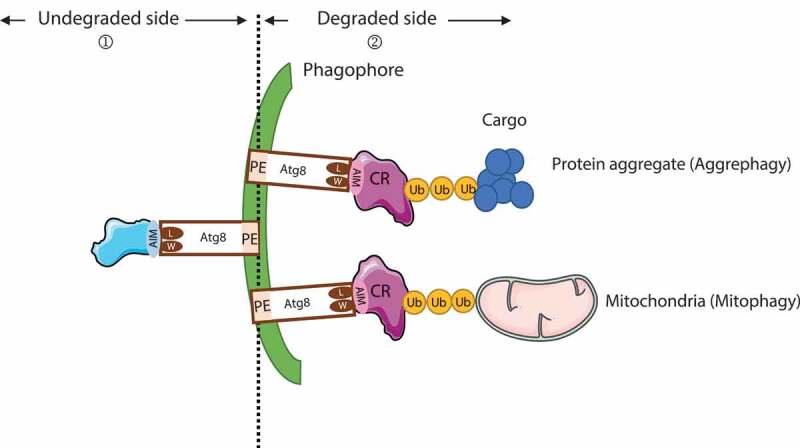

Atg8-family proteins have also been described to be involved in selective autophagy [37]. During selective autophagy (Figure 3), lipidated Atg8-family proteins bind to a cargo receptor, which is itself interacting with the cargo (mitochondria, protein aggregate, peroxisome, bacteria …) to induce its recruitment into the forming autophagic vesicle [2]. The cargo receptor interacts with two conserved hydrophobic pockets of Atg8-family proteins called W-site and L-site through their AIM motif (Atg8-interaction motif), which is called LIR (LC3-interacting region) for the LC3s [73] and GIM (GABARAP-interacting motif) for the GABARAPs [74].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of Atg8-family protein (Atg8) involvement during selective autophagy and recruitment. ① Atg8-family proteins are docked at the phagophore membrane by their lipidation and act as recruiters of proteins that will not be degraded through autophagy. These proteins are brought to the autophagosome external membrane (convex side) to allow an efficient autophagosome formation and include proteins such as GABARAP, ULK1, and PtdIns3K-C1 complexes during the early stage of autophagy or with the lysosomal proteins BIRC6, PLEKHM1, ATG2, and PI4K2A during autophagosome-lysosome fusion. ② During selective autophagy, Atg8-family proteins interact with the cargo receptor (CR) through the W and L hydrophobic pockets of Atg8-family proteins with the AIM of the CR. The CR interacts with the ubiquitinated cargo (e.g., mitochondria, protein aggregates) to facilitate degradation

The specificity of selective autophagy may occur at two levels: i) The involvement of a specific cargo receptor in one or several types of selective autophagy. Indeed, a dozen of cargo receptors have already been described to be involved in different types of selective autophagy. If some of them have been described to be involved in several types of selective autophagy, e.g., SQSTM1 (sequestosome 1) which is implicated in aggrephagy, xenophagy, and mitophagy [75], others have been described to be implicated, and indispensable, in only one selective autophagy, e.g., BNIP3 L/NIX (BCL2 interacting protein 3 like) in mitophagy during reticulocyte maturation [76]. ii) The ability of the cargo receptor to interact preferentially with only one or several Atg8-family proteins. The cargo receptors SQSTM1, NBR1 (NBR1 autophagy cargo receptor), and OPN (optineurin) can interact with all Atg8-family proteins [77,78]. However, during PINK1 (PTEN induced kinase 1)-PRKN/Parkin (parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase) mitophagy, only GABARAPs, but not the LC3s, have been shown to be necessary [42]. Moreover, it has been shown that CALCOCO2/NDP52 (calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 2) binds specifically LC3C during xenophagy. It has also been described that BNIP3 (BCL2 interacting protein 3) and FUNDC1 (FUN14 domain containing 1) preferentially recruit LC3B, while FKBP8 (FKBP prolyl isomerase 8) preferentially recruits LC3A [79–81].

It was first described that the cargo receptor interacts with one Atg8-family protein through its AIM motif, but recently, it has been demonstrated that cargo receptor-Atg8-family proteins interaction preferences are also linked to the N- and C-terminal acidic amino acids flanking the AIM motif. Indeed, Atkinson and collaborators [82] have shown that the C-terminal cysteine is required for the high affinity with LC3A and LC3B, while the aspartic amino acid is important for LC3C binding. For GABARAP binding, the N- and C-terminal residues of the AIM motif are involved in the interaction.

Selective recruitment of different cargos by the Atg8-family proteins induce the selective degradation of target proteins but also the selective recruitment of factors to the cytosolic side of autophagosomes, which will not be degraded by autophagy (Figure 3). Indeed, the recruitment of non-degraded proteins by Atg8-family proteins conjugated to the outer membrane of the autophagosome has been shown to be necessary to induce efficient autophagy. GABARAP induced an efficient autophagy initiation through the recruitment of ULK1 and PtdIns3K-C1 complexes, an efficient elongation through its interaction with ATG2s, and an efficient fusion through the recruitment of PLEKHM1, BIRC6, and PI4K2A. Moreover, LC3 induced an efficient perinuclear re-localization of autophagosomes through its interaction with microtubules and molecular motors.

Atg8-family proteins have been described to present redundant functions in cells. Indeed, in plants, some species present more than 20 Atg8 isoforms, which may contribute to the functional diversification of selective autophagy. A recent study, performed in plants tried to highlight the biochemical basis of Atg8-family proteins specialization and has shown that the N-terminal beta-strand of Atg8-family proteins mediated discriminatory binding to the cargo receptor [83]. However, in cells, more studies will be needed in the future to characterize the specific role of each Atg8-family proteins in the different selective autophagy pathways.

Atg8-family proteins as prognosis factors and their functions in cancer

The expression and role of Atg8-family proteins in cancer remain largely undescribed and controversial. Here, we focused on the study of the data available on the expression of GABARAPs and LC3s in cancer compared to normal cells (Table 1) to determine whether Atg8-family proteins might be used as prognosis factors. Moreover, we clarified the pro-tumor and anti-tumor roles of Atg8-family proteins during cancer.

Table 1.

Atg8-family protein expression in cancers is correlated with a favorable prognosis or an unfavorable prognosis depending on tumor type

| Good prognosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor types | mRNA study | Protein study | ||

| GABARAPs | GABARAP | Pancreatic cancer [89] | High expression associated with longer overall survival, Kaplan Meier curve | |

| Neuroblastoma [90] | High expression associated with longer overall survival, Kaplan Meier curve | |||

| Liver cancer [40] | Low expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissue in patient | |||

| GABARAPL1 | Hematopoietic tumor (AML) [88,89] | Low expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissues in patient | ||

| Renal cancer [89] | High expression is associated with longer overall survival | |||

| Prostate cancer [87] | Low expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissues in patient | Low expression of GABARAPL1 correlated with shorter survival rate | ||

| Low expression correlated with shorter diseases free time and with aggressiveness | ||||

| Breast cancer [85,91] | Expression decrease with stage advancement | |||

| Liver cancer [40,89] | Lower expression in cancer cells compare to normal tissues in patient | Low expression in cancer cells compared to normal cells in patient | ||

| High expression is correlated with longer overall survival, Kaplan Meier curve | ||||

| GABARAPL2 | Renal cancer [89] | High expression is associated with longer overall survival | ||

| Breast cancer [85] | Lower expression in cancer cells compared to normal cells | |||

| Hematopoietic tumor (AML) [88] | Lower expression in cancer cells compared to normal cells | |||

| LC3 s | LC3 (unspecified member) | Ovary cancer [96] | Expression decreased with stage advancement | |

| Low expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissues in patient | ||||

| Prostate cancer [93] | Lower expression in cancer cells compare to normal tissues in patient | |||

| Lung cancer [92] | Lower expression in cancer cells compare to normal tissue in patient | Lower expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissue in patient | ||

| Cervical squamous carcinoma [95] | Lower expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissue in patient | |||

| Papillary thyroid cancer [97] | Lower expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissue in patient | |||

| LC3A | Pancreatic cancer [89] | High expression is associated with long overall survival, Kaplan Meier curve | ||

| LC3B | Renal carcinoma [89,93] | High expression is associated with long overall survival, Kaplan Meier curve | High expression is associated with longer overall survival, Kaplan Meier curve | |

| Low expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissues in patient | Lower expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissues in patient | |||

| Gastric cancer [98] | Lower expression in cancer cells compared to normal tissues in patient | |||

| High expression is associated with longer overall survival, Kaplan Meier curve | ||||

| LC3 C | ||||

The regulation of Atg8-family proteins expression

As said before, Atg8-family proteins act as markers of autophagosome formation, and indicators of autophagosome number in cells, and are widely used to characterize and quantify the autophagy flux. Indeed, the general idea is that the variable expression of Atg8-family proteins may correlate to the level of autophagy flux in cancer cells. However, the levels of Atg8-family proteins in cells may also result from a specific regulation of expression induced by different cellular stresses or pathways not directly linked to the autophagy process. It has been described, for example, that a decrease of GABARAP, GABARAPL1, and LC3 expressions is linked to epigenetic modifications in several cancers [84–86] but also to the constitutive activation of intracellular pathways [87]. In MCF-7 breast cancer cells, the GABARAPL1 promoter has, for example, been shown to be highly methylated, and to present deacetylation of the histone H3 leads to chromatin condensation and decreased GABARAPL1 expression [85]. In HeLa cells, it has also been shown that LC3, GABARAPL1, and GABARAPL2 expressions are repressed by the EHMT2/G9A methyltransferase [84]. In contrast, in the case of prostate cancers, the downregulation of GABARAPL1 has been explained by the constitutive activation of the AKT pathway and the inactivation of the transcription factors FOXOs (Forkhead box transcription factor of the O class) [87].

Atg8-family proteins as prognosis markers for tumor progression and outcome

Atg8-family proteins levels as a good prognosis marker

The expression and role of the Atg8-family proteins in cancer etiology still remain largely undescribed and controversial. However, in numerous mRNA studies, the expression of GABARAPs has been described as downregulated in cancers, and their high expression has been linked to favorable prognosis in hematopoietic cancer, renal cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [40,85,87–89] (Table 1). For example, the loss of GABARAPL1 expression has been associated with poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma and correlated with advanced stages of neuroblastoma [40,90]. Similarly, protein studies have confirmed a decrease of GABARAP expression in breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma [40,91]. Similarly, it has been shown that LC3 (unspecified member) mRNAs are reduced in lung cancer and that low levels of LC3B mRNA and protein are correlated with advanced stages of cancer and poor prognosis in renal carcinoma [92,93]. Moreover, high levels of LC3A mRNA are correlated with increased overall survival [89]. Protein studies have also shown that LC3s (unspecified member) levels are reduced in prostate cancer, papillary thyroid cancer, cervical squamous cell carcinoma, lung cancer, and advanced stages in ovary cancer [92,94–97]. Then, a decrease of LC3B proteins is correlated with advanced stages and poor prognosis in renal carcinoma [93] and with the presence of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer [98]. Finally, high expression of LC3B (mRNA and protein) has been correlated with a good prognosis in renal cancer [99] (Table 1).

Atg8-family proteins levels as a poor prognosis marker

Surprisingly, Atg8-family proteins can also be associated with cancer growth, aggressiveness, and poor prognosis (Table 1). Indeed, high expression of GABARAPs is associated with shorter overall survival and disease-free survival in head and neck (mRNA level), thyroid, or colorectal cancer (protein level) [100–102]. Similarly, LC3 protein levels (unspecified member) is also upregulated in gastrointestinal cancers [103] and correlates with poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma [104] and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [105]. Moreover, high levels of LC3B mRNA correlates to poor prognosis in stomach cancer and triple-negative breast cancers, respectively [89,106]. At the protein level, LC3B is elevated in melanoma metastasis and associates with aggressiveness in breast cancer [107,108].

Molecular mechanism of Atg8-family proteins during cancer progression

The anti-tumor role of Atg8-family proteins

To determine whether GABARAPL1 can be considered as a tumor suppressor protein, several studies conducted in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, HepG2 and HepG3 hepatocellular carcinoma cells, in which GABARAPL1 was overexpressed, human LNCaP prostate cancer cells, and MDA-MB-436 breast cancer cells, in which GABARAPL1 was knocked-down, have shown that GABARAPL1, indeed, inhibited cell proliferation, invasion, and tumor growth [41,63,87,91,109]. Similarly, the tumor-suppressive functions of GABARAP have been studied in ovary cancers and breast cancers, and the overexpression of GABARAP led to a decrease in cell viability, migration, and proliferation [110]. To our knowledge, regarding the function of GABARAPL2 and LC3s in cancer progression, very few studies have been published. However, a study realized in transformed embryonic human kidney cells, the HEK293 cell line, has demonstrated a role of LC3B in the inhibition of oncogene-induced senescence [39], and a recent study on the implication of LC3C, conducted in HeLa cells, has shown that LC3C leads to the selective degradation of the HGF (hepatocyte growth factor) receptor, MET, inhibiting HGF-induced cell migration and invasion [111].

The tumor-suppressive function of the Atg8-family proteins has been suggested to be linked to their role in the degradation of oncogenic proteins or dysfunctional organelles. Indeed, the tumor-suppressive functions of Atg8-family proteins have been previously linked to their involvement in the selective degradation of BNIP3L, mitochondria, or SQSTM1 [63,109,112]. The defect in the degradation of mitochondria or BNIP3L led to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, cytoskeleton reorganization, and cell aggressiveness [63,113–115]. The alteration of SQSTM1 degradation has also been described to lead to the deregulation of glucose metabolism and increased tumor promotion, as described in numerous cancer cases (hepatocellular, gastric, breast, and prostate cancers) [113]. Moreover, GABARAP and GABARAPL1 tumor-suppressive functions have also been related to their involvement in the selective degradation of DVL2 (disheveled segment polarity protein 2). Indeed, a defect in DVL2 degradation led to the activation of the WNT signaling gene family (WNT) pathway and, consequently, to the increase of tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma [109]. Similarly, the implication of LC3B in cancer progression has been linked to its role in LMNB1 (lamin B1) selective degradation [39], leading to the decrease in cell proliferation and induced senescence [116]. It has also been shown that LMNB1 can interact with LC3A, LC3C, and GABARAPs [39]. At last, it has been shown that the selective degradation of transcription factors implicated in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), such as SNAI1 (snail family transcriptional repressor 1) or TWIST1 (twist family bHLH transcription factor 1), led to a decrease in tumor cell aggressiveness [117,118].

Altogether, these studies demonstrate a role for Atg8-family proteins in cancer progression, but more recent data also highlight the fact that the non-lipidated forms of the Atg8-family proteins may also play a role in cancer, which may be independent of their localization to autophagosomes [41]. Some in vitro studies performed in MCF-7 breast cancer cells have, indeed, proven the importance of the lipidation of the Atg8-family proteins and their association with the autophagosomes since GABARAPL1, but not GABARAPL1G116A, leads to a decrease in cell proliferation [40], clonogenicity, invasion, and adhesion [41], and that LC3, but not LC3G120A, can interact with LMNB1 [39] in order to regulate cellular proliferation and senescence. However, other studies also demonstrate that GABARAPL1G116A, like GABARAPL1, leads to a decrease of in vitro cell migration and in vivo tumor growth [41]. These results suggest that the role of the Atg8-family proteins in cancers may also be independent of their involvement in the selective degradation of specific substrates but may also involve the inhibition of important regulators of tumor formation, such as MTOR, a protein implicated in tumor progression and cell proliferation [119]. However, these results do not imply that the function of the Atg8-family proteins in cancers is fully independent of their role in autophagy. Indeed, the GABARAPL1G116A mutant, like GABARAPL1, can activate the initiation of autophagy via the inhibition of MTOR activity and in the activation of AMPK, leading to ULK1 activation [41]. GABARAPG116A, GABARAPL2G116A, and LC3G120A mutants have also been designed, but their involvement during cancer progression has not been studied yet [21,28].

To conclude, the tumor-suppressive functions of Atg8-family protein appears to be mainly linked to their function in the selective degradation of oncogenic proteins or damaged organelles, but recent data also suggest that the cytosolic forms of the Atg8-family proteins may also play a role in tumor suppression [41]. Moreover, we cannot exclude that their tumor-suppressive function may be linked to their capacity to regulate different cellular signaling pathways. Indeed, it has already been shown that GABARAP can induce a cell cycle arrest through the upregulation of TRP53/p53 leading to decreased cell viability, migration, and proliferation in ovary and breast cancer cells [110] but also through the downregulation of the PI3K (phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase)-AKT (AKT serine/threonine kinase) signaling pathways leading to the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and proliferation in ovarian cancer cells [120].

The pro-tumor role of Atg8-family proteins

The oncogenic function of Atg8-family proteins has been studied in triple-negative breast cancer cells, such as MDA-MB-231 or BT549, in which the knockdown of GABARAPL1 leads to a decrease in cell proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, and in vivo tumor growth, and metastasis [121]. Similarly, it has been described that the knockdown of GABARAPL1 decreases cell proliferation in prostate cancer cells because of a defect of the translocation of the androgen receptor (AR) to the nucleus. GABARAPL1 may, therefore, be involved in AR scaffolding by regulating its transcriptional activity [122]. The role of LC3B during cancer promotion has also been suggested to be linked to the regulation of various cellular signaling pathways. Indeed, LC3B has been described to act as a scaffold protein on the outer membrane of the autophagosome to allow for efficient coordination of the RAF1-MAP2K/MEK-MAPK1/ERK signaling pathway thanks to the interaction of LC3B with MAPK1 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 1) [123]. These results suggest that an increase in LC3B can lead to the activation of the pathway based on observations already made in numerous cancers, such as renal, hepatocellular, lung, melanoma, and thyroid cancers [124]. Similarly, it has been described that LC3B, GABARAP, and GABARAPL1 induces the localization of MAPK15/ERK8 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 15) to the autophagosome and, therefore, autophagy related to cellular proliferation in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [125,126]. Moreover, we can hypothesize that the involvement of the Atg8-family proteins in cellular trafficking could also be implicated in cancer progression. Indeed, GABARAPs have been involved in GABRA1 receptor trafficking to the plasma membrane [19], and it has been shown that the overactivation of the GABRA1 receptor in prostate cancer can be linked to cancer cell progression [127].

Altogether, these data demonstrate that the GABARAPs were mostly downregulated in cancer cells and that these proteins may act as tumor suppressors, whereas the expression and the role of the LC3s in cancers remain unclear and controversial. Even if the characterization of the Atg8-family proteins as tumor suppressors seems to be linked to their implication in the selective degradation of oncogenic factors and dysfunctional organelles, more studies will be needed to confirm that the cytosolic forms of these proteins might also play a role in tumor promotion and growth, independently of their function in the autophagy process.

Conclusion

All Atg8-family proteins share a high percentage of identity at the nucleotide and protein levels [15]. They all present a conserved glycine in their C-terminus, a necessary and essential residue useful for their conjugation to phospholipids and their association to the autophagosomes [21]. During autophagy, all Atg8-family proteins have also been shown to be involved in the elongation of the phagophore and during basal and induced autophagy. However, it appears that autophagy can also occur in the absence of all Atg8-family proteins to a lesser extent, and in the absence of one of the Atg8 subfamily, the other proteins could compensate for this absence. These conclusions raise the question about the redundancy or specialization of human Atg8-family proteins. Indeed, in unicellular organisms, such as yeast, only one member, named Atg8, has been described, and this observation, therefore, suggests that the family expanded significantly during evolution [128]. More studies point out the specialization of Atg8-family proteins because of their significant differences in their primary amino-acid sequences, mostly their N-terminus [74], and in their AIM motif [129], two regions which have been described to control their interactions with partner proteins. Moreover, the amino-acid sequences around the AIM motif were also described to be involved in the specificity of the interaction between cargoes and Atg8-family proteins. These observations led to the understanding of the different roles of GABARAPs and LC3s during the autophagy process. GABARAPs mainly act as recruiters of downstream autophagy actors during the initiation process and during the autophagosome-lysosome fusion, whereas LC3s seems to be mostly involved in autophagosome movement and re-localization.

Autophagy is a double-edge sword during cancer progression since induced autophagy in the tumor microenvironment can provide the necessary nutrients to cancer cells, sustain their metabolism, and allow for survival following increased cellular stresses. It may also induce cancer cell death following excessive induced autophagy degradation. These observations suggest that inhibiting or activating autophagy may become a good strategy to inhibit cancer progression. Indeed, hydroxychloroquine is already currently used in clinical trials to inhibit autophagy and treat ER+ breast cancers (NCT02414776) [130], while MTOR inhibitors are currently used to activate autophagy to treat metastatic pancreatic cancers (NCT00409292). However, developing more specific strategies to target individual autophagy actors without affecting the whole autophagy pathway may become a new line of treatment in the future. Nevertheless, such an applied therapeutic approach would need a high degree of knowledge of the distinct functions of each autophagy actors in the process of autophagy and in the context of specific cancers. One example of such a protocol is the use of a specific inhibitor of ATG4B, named NSC185058, to specifically target Atg8-family proteins lipidation and to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy in osteosarcoma and radiotherapy in glioblastoma in mice [131,132]. However, during cancer progression, the GABARAPs appeared to be mainly downregulated, and their loss-of-expression can be correlated to poor prognosis, whereas LC3s appeared to be either downregulated or upregulated. Two explanations might be plausible to explain these discrepancies. First, a decrease of the expression of Atg8-family proteins may be strictly linked to a decrease of autophagy in cancer cells, suggesting that their levels in tumors might only be correlated to autophagy flux. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude that, during cancer, the expression of Atg8-family proteins might also be specifically regulated by other pathways, independent of the regulation of the autophagy pathway. The tumor-suppressive functions of the Atg8-family proteins in cancers might, therefore, be independent of their roles in autophagy but seemed to be linked to their role in the selective degradation of oncogenic proteins, as well as damaged organelles through autophagy and their role in the regulation of autophagy initiation. The specialization of the Atg8-family proteins described above may explain these differences observed between GABARAPs and LC3s during cancer progression. Nevertheless, we cannot ignore that Atg8-family proteins may also present a role in immune cells implicated in the anti-tumor immune response. Firstly, GABARAP appeared to be necessary to develop an efficient anti-tumor immune response through its implication in cytokine secretion [133]. Then, LC3s have been shown to be important for efficient extracellular antigen processing, presentation, and induction of T-cell anti-tumor response by dendritic cells in mice [24,134]. The role of the LC3s during antigen presentation involves the LAP, a mechanism implicated in tumor growth, which is only described for the LC3 proteins but not for GABARAPs.

The new information published about the specificity of Atg8-family proteins-cargo interaction will allow, in the future, for the development of specific inhibitors targeting each Atg8-family protein to dissect their biological role and their potential as a therapeutic solution [82]. Indeed, Atg8-family proteins may also be involved in genome expression reprogramming during cancer progression through the specific degradation of transcription factors or co-regulators. For example, selective autophagy has been described to be implicated in the degradation of EMT transcription factors [118], and more recently, it has been shown that GABARAPL1, GABARAPL2, and GABARAP, but not LC3B, induced the selective degradation of the co-repressor NCOR1 (nuclear receptor corepressor 1), leading to the maintenance of metabolism in response to nutrient deprivation. Because the downregulation of the co-repressor NCOR is involved in cancer progression [135], it has been suggested that the inhibition of the expression of GABARAPs might become a good strategy to inhibit cancer cell proliferation during nutrient starvation, a condition usually encountered in the tumor microenvironment [136].

Here, we highlighted, for the first time, that Atg8-family proteins may present redundant roles during the general autophagy process, but each subfamily of GABARAPs and LC3s also present specific functions during autophagy by regulating the recruitment of downstream proteins or autophagosome movement, respectively. Each Atg8-family protein may also present specific roles thanks to the specific AIM motifs flanked by N- and C-terminal amino-acids involved in the affinity binding and specificity with their respective partners. These specific features might be used to develop new anti-cancer therapies, in particular, regarding therapies that target GABARAPs because of their anti-tumor role described in many cancer cases.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Xie Z, Klionsky DJ.. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Birgisdottir ÅB, Lamark T, Johansen T. The LIR motif - crucial for selective autophagy. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:3237–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ashford TP, Porter KR. Cytoplasmic components in hepatic cell lysosomes. J Cell Biol. 1962;12:198–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fortun J, Dunn WA, Joy S, et al. Emerging Role for Autophagy in the Removal of Aggresomes in Schwann Cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10672–10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lamark T, Johansen T. Aggrephagy: selective disposal of protein aggregates by macroautophagy. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:736905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Folkerts H, Hilgendorf S, Vellenga E, Bremer E, Wiersma VR. The multifaceted role of autophagy in cancer and the microenvironment. Med Res Rev. 2019;39:517–560. doi: 10.1002/med.21531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].He H, Dang Y, Dai F, et al. Post-translational Modifications of Three Members of the Human MAP1LC3 Family and Detection of a Novel Type of Modification for MAP1LC3B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29278–29287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Legesse-Miller A, Sagiv Y, Porat A, et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Low Molecular Weight Protein Involved in Intra-Golgi Traffic. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3105–3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mann SS, Hammarback JA. Molecular characterization of light chain 3. A microtubule binding subunit of MAP1A and MAP1B. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11492–11497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mansuy V, Boireau W, Fraichard A, et al. GEC1, a protein related to GABARAP, interacts with tubulin and GABA(A) receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pellerin I, Vuillermoz C, Jouvenot M, et al. Identification and characterization of an early estrogen-regulated RNA in cultured guinea-pig endometrial cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1993;90:R17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sagiv Y, Legesse-Miller A, Porat A, et al. GATE-16, a membrane transport modulator, interacts with NSF and the Golgi v-SNARE GOS-28. Embo J. 2000;19:1494–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang H, Bedford FK, Brandon NJ, et al. GABA(A)-receptor-associated protein links GABA(A) receptors and the cytoskeleton. Nature. 1999;397:69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Xin Y, Yu L, Chen Z, et al. Cloning, Expression Patterns, and Chromosome Localization of Three Human and Two Mouse Homologues of GABAA Receptor-Associated Protein. Genomics. 2001;74:408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Le Grand JN, Chakrama FZ, Seguin-Py S, et al. GABARAPL1 (GEC1): original or copycat? Autophagy. 2011;7:1098–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Coyle JE, Qamar S, Rajashankar KR, et al. Structure of GABARAP in two conformations: implications for GABA(A) receptor localization and tubulin binding. Neuron. 2002;33:63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Satoo K, Noda NN, Kumeta H, et al. The structure of Atg4B–LC3 complex reveals the mechanism of LC3 processing and delipidation during autophagy. Embo J. 2009;28:1341–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen Z-W, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor associated proteins: a key factor regulating GABAA receptor function. J Neurochem. 2007;100:279–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chen C, Wang Y, Huang P, et al. Effects of C-terminal modifications of GEC1 protein and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA(A)) receptor-associated protein (GABARAP), two microtubule-associated proteins, on kappa opioid receptor expression. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15106–15115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chakrama FZ, Seguin-Py S, Le Grand JN, et al. GABARAPL1 (GEC1) associates with autophagic vesicles. Autophagy. 2010;6:495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, et al. LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form-II formation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2805–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and Autophagy. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;445:77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sanjuan MA, Dillon CP, Tait SWG, et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;450:1253–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Münz C. Antigen Processing by Macroautophagy for MHC Presentation. Front Immunol. [Internet]. 2011. [cited 2019 January28];2. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3342048/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Winer H, Fraiberg M, Abada A, et al. Autophagy differentially regulates TNF receptor Fn14 by distinct mammalian Atg8 proteins. Nat Commun. [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2019 February5];9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6138730/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Betin VMS, Lane JD. Caspase cleavage of Atg4D stimulates GABARAP-L1 processing and triggers mitochondrial targeting and apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2554–2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kirisako T, Ichimura Y, Okada H, et al. The reversible modification regulates the membrane-binding state of Apg8/Aut7 essential for autophagy and the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:263–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Scherz-Shouval R, Sagiv Y, Shorer H, et al. The COOH terminus of GATE-16, an intra-Golgi transport modulator, is cleaved by the human cysteine protease HsApg4A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14053–14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. Human Light Chain 3/MAP1LC3B Is Cleaved at Its Carboxyl-terminal Met121 to Expose Gly120 for Lipidation and Targeting to Autophagosomal Membranes.. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47704–47710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sou Y, Tanida I, Komatsu M, et al. Phosphatidylserine in addition to phosphatidylethanolamine is an in vitro target of the mammalian Atg8 modifiers, LC3, GABARAP, and GATE-16. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3017–3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Weidberg H, Shvets E, Shpilka T, et al. LC3 and GATE-16/GABARAP subfamilies are both essential yet act differently in autophagosome biogenesis. Embo J. 2010;29:1792–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sou Y, Waguri S, Iwata J, et al. The Atg8 Conjugation System Is Indispensable for Proper Development of Autophagic Isolation Membranes in Mice. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4762–4775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Alemu EA, Lamark T, Torgersen KM, et al. ATG8 Family Proteins Act as Scaffolds for Assembly of the ULK Complex: SEQUENCE REQUIREMENTS FOR LC3-INTERACTING REGION (LIR) MOTIFS. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:39275–39290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nakatogawa H, Ichimura Y, Ohsumi Y. Atg8, a Ubiquitin-like Protein Required for Autophagosome Formation, Mediates Membrane Tethering and Hemifusion. Cell. 2007;130:165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Knorr RL, Nakatogawa H, Ohsumi Y, et al. Membrane Morphology Is Actively Transformed by Covalent Binding of the Protein Atg8 to PE-Lipids. PLoS One. [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2019 January23];9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4270758/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cherra SJ, Kulich SM, Uechi G, et al. Regulation of the autophagy protein LC3 by phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:533–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Alam J, DeHaro D, Redding KM, et al. C-Terminal Processing of GABARAP is Not Required for Trafficking of the Angiotensin II Type 1A Receptor. Regul Pept. 2010;159:78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dou Z, Xu C, Donahue G, et al. Autophagy mediates degradation of nuclear lamina. Nature. 2015;527:105–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu C, Xia Y, Jiang W, et al. Low expression of GABARAPL1 is associated with a poor outcome for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:2043–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Poillet-Perez L, Jacquet M, Hervouet E, et al. GABARAPL1 tumor suppressive function is independent of its conjugation to autophagosomes in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:55998–56020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nguyen TN, Padman BS, Usher J, et al. Atg8 family LC3/GABARAP proteins are crucial for autophagosome–lysosome fusion but not autophagosome formation during PINK1/Parkin mitophagy and starvation. J Cell Biol. 2016. 215:857–874.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Vaites LP, Paulo JA, Huttlin EL, et al. Systematic Analysis of Human Cells Lacking ATG8 Proteins Uncovers Roles for GABARAPs and the CCZ1/MON1 Regulator C18orf8/RMC1 in Macroautophagic and Selective Autophagic Flux. Mol Cell Biol. 2018;38:e00392–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Szalai P, Hagen LK, Sætre F, et al. Autophagic bulk sequestration of cytosolic cargo is independent of LC3, but requires GABARAPs. Exp Cell Res. 2015;333:21–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hosokawa N, Sasaki T, Iemura S, et al. Atg101, a novel mammalian autophagy protein interacting with Atg13. Autophagy. 2009;5:973–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, et al. Beclin 1 Forms Two Distinct Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Complexes with Mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5360–5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zachari M, Ganley IG. The mammalian ULK1 complex and autophagy initiation. Essays Biochem. 2017;61:585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Grunwald DS, Otto NM, Park J-M, et al. GABARAPs and LC3s have opposite roles in regulating ULK1 for autophagy induction. Autophagy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Joachim J, Jefferies HBJ, Razi M, et al. Activation of ULK Kinase and Autophagy by GABARAP Trafficking from the Centrosome Is Regulated by WAC and GM130. Mol Cell. 2015;60:899–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Joachim J, Razi M, Judith D, et al. Centriolar Satellites Control GABARAP Ubiquitination and GABARAP-Mediated Autophagy. Curr Biol. 2017;27:2123-2136.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kraft C, Kijanska M, Kalie E, et al. Binding of the Atg1/ULK1 kinase to the ubiquitin-like protein Atg8 regulates autophagy. Embo J. 2012;31:3691–3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Matsunaga K, Morita E, Saitoh T, et al. Autophagy requires endoplasmic reticulum targeting of the PI3-kinase complex via Atg14L. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:511–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Birgisdottir ÅB, Mouilleron S, Bhujabal Z, et al. Members of the autophagy class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex I interact with GABARAP and GABARAPL1 via LIR motifs. Autophagy. 2019;15:1333–1355.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Xie Z, Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Atg8 Controls Phagophore Expansion during Autophagosome Formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3290–3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Landajuela A, Hervás JH, Antón Z, et al. Lipid Geometry and Bilayer Curvature Modulate LC3/GABARAP-Mediated Model Autophagosomal Elongation. Biophys J. 2016;110:411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bozic M. Bekerom L van den, Milne BA, et al. A conserved ATG2-GABARAP interaction is critical for phagophore closure. bioRxiv. 2020;21:e48412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kaufmann A, Beier V, Franquelim HG, et al. Molecular mechanism of autophagic membrane-scaffold assembly and disassembly. Cell. 2014;156:469–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Jahreiss L, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC. The itinerary of autophagosomes: from peripheral formation to kiss-and-run fusion with lysosomes. Traffic. 2008;9:574–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ebner P, Poetsch I, Deszcz L, et al. The IAP family member BRUCE regulates autophagosome–lysosome fusion. Nat Commun. 2018;9:599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].McEwan DG, Dikic I. PLEKHM1: adapting to life at the lysosome. Autophagy. 2015;11:720–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wang H, Sun H-Q, Zhu X, et al. GABARAPs regulate PI4P-dependent autophagosome: lysosomefusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:7015–7020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Gu Y, Princely Abudu Y, Kumar S, et al. Mammalian Atg8 proteins regulate lysosome and autolysosome biogenesis through SNAREs. Embo J. 2019;38:e101994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Boyer-Guittaut M, Poillet L, Liang Q, et al. The role of GABARAPL1/GEC1 in autophagic flux and mitochondrial quality control in MDA-MB-436 breast cancer cells. Autophagy. 2014;10:986–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Fass E, Shvets E, Degani I, et al. Microtubules Support Production of Starvation-induced Autophagosomes but Not Their Targeting and Fusion with Lysosomes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36303–36316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dynein-dependent movement of autophagosomes mediates efficient encounters with lysosomes. Cell Struct Funct. 2008;33:109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kouno T, Mizuguchi M, Tanida I, et al. Solution structure of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 and identification of its functional subdomains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24610–24617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Pankiv S, Alemu EA, Brech A, et al. FYCO1 is a Rab7 effector that binds to LC3 and PI3P to mediate microtubule plus end–directed vesicle transport. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:253–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Fu M, Nirschl JJ, Holzbaur ELF. LC3 Binding to the Scaffolding Protein JIP1 Regulates Processive Dynein-Driven Transport of Autophagosomes. Dev Cell. 2014;29:577–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wang H, Olsen RW. Binding of the GABA(A) receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) to microtubules and microfilaments suggests involvement of the cytoskeleton in GABARAPGABA(A) receptor interaction. J Neurochem. 2000;75:644–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Kumar S, Jain A, Farzam F, et al. Mechanism of Stx17 recruitment to autophagosomes via IRGM and mammalian Atg8 proteins. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:997–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Albanesi J, Wang H, Sun H-Q, et al. GABARAP-mediated targeting of PI4K2A/PI4KIIα to autophagosomes regulates PtdIns4P-dependent autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy. 2015;11:2127–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Zhang X, Wang L, Lak B, et al. GRASP55 Senses Glucose Deprivation through O-GlcNAcylation to Promote Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion. Dev Cell. 2018;45:245–261.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].von Muhlinen N, Akutsu M, Ravenhill BJ, et al. LC3C, Bound Selectively by a Noncanonical LIR Motif in NDP52, Is Required for Antibacterial Autophagy. Mol Cell. 2012;48:329–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Rogov VV, Stolz A, Ravichandran AC, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the GABARAP interaction motif (GIM). EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1382–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Xu Z, Yang L, Xu S, et al. The receptor proteins: pivotal roles in selective autophagy. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2015;47:571–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Novak I, Kirkin V, McEwan DG, et al. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Johansen T, Lamark T. Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy. 2011;7:279–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wild P, Farhan H, McEwan DG, et al. Phosphorylation of the Autophagy Receptor Optineurin Restricts Salmonella Growth. Science. 2011;333:228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Bhujabal Z, Birgisdottir ÅB, Sjøttem E, et al. FKBP8 recruits LC3A to mediate Parkin‐independent mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:947–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Hanna RA, Quinsay MN, Orogo AM, et al. Microtubule-associated Protein 1 Light Chain 3 (LC3) Interacts with Bnip3 Protein to Selectively Remove Endoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondria via Autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19094–19104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Liu L, Feng D, Chen G, et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Atkinson JM, Ye Y, Gebru MT, et al. Time-resolved FRET and NMR analyses reveal selective binding of peptides containing the LC3-interacting region to ATG8 family proteins. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:14033-14042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Zess EK, Jensen C, Cruz-Mireles N, et al. N-terminal β-strand underpins biochemical specialization of an ATG8 isoform. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Artal-martinez de Narvajas A, Gomez TS, Zhang J-S, et al. Epigenetic Regulation of Autophagy by the Methyltransferase G9a. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:3983–3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Hervouet E, Claude-Taupin A, Gauthier T, et al. The autophagy GABARAPL1 gene is epigenetically regulated in breast cancer models. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Klebig C, Seitz S, Arnold W, et al. Characterization of {gamma}-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-associated protein, a novel tumor suppressor, showing reduced expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Su W, Li S, Chen X, et al. GABARAPL1 suppresses metastasis by counteracting PI3K/Akt pathway in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;8:4449–4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Brigger D, Torbett BE, Chen J, et al. Inhibition of GATE-16 attenuates ATRA-induced neutrophil differentiation of APL cells and interferes with autophagosome formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;438:283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Uhlen M, Zhang C, Lee S, et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science. 2017;357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Roberts SS, Mori M, Pattee P, et al. GABAergic system gene expression predicts clinical outcome in patients with neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4127–4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Berthier A, Seguin S, Sasco AJ, et al. High expression of gabarapl1 is associated with a better outcome for patients with lymph node-positive breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1024–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Jiang Z-F, Shao L-J, Wang W-M, et al. Decreased expression of Beclin-1 and LC3 in human lung cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Deng Q, Wang Z, Wang L, et al. Lower mRNA and protein expression levels of LC3 and Beclin1, markers of autophagy, were correlated with progression of renal clear cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Liu C, Xu P, Chen D, et al. Roles of autophagy-related genes Beclin-1 and LC3 in the development and progression of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Biomed Rep. 2013;1:855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Hu Y-F, Lei X, Zhang H-Y, et al. Expressions and clinical significance of autophagy-related markers Beclin1, LC3, and EGFR in human cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:2243–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Shen Y, Liang L-Z, Hong M-H, et al. [Expression and clinical significance of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and Beclin1 in epithelial ovarian cancer]. Ai Zheng. 2008;27:595–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Li X, Lin X, Ma H. Overexpression of LC3 in Papillary Thyroid Carcinomas and Lymph Node Metastases. Acta Chir Belg. 2015;115:356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Yu S, Li G, Wang Z, et al. Low expression of MAP1LC3B, associated with low Beclin-1, predicts lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Tumor Biol. 2016;37:15007–15017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Wu S, Sun C, Tian D, et al. Expression and clinical significances of Beclin1, LC3 and mTOR in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3882–3891. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Keulers TG, Schaaf MBE, Peeters HJM, et al. GABARAPL1 is required for increased EGFR membrane expression during hypoxia. Radiother Oncol. 2015;116:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Roberts SS, Mendonça-Torres MC, Jensen K, et al. GABA receptor expression in benign and malignant thyroid tumors. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Miao Y, Zhang Y, Chen Y, et al. GABARAP is overexpressed in colorectal carcinoma and correlates with shortened patient survival. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Yoshioka A, Miyata H, Doki Y, et al. LC3, an autophagosome marker, is highly expressed in gastrointestinal cancers. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Wu W-Y, Kim H, Zhang C-L, et al. Clinical significance of autophagic protein LC3 levels and its correlation with XIAP expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2014;31:108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Chen Y, Li X, Wu X, et al. Autophagy-related proteins LC3 and Beclin-1 impact the efficacy of chemoradiation on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:562–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Lefort S, Joffre C, Kieffer Y, et al. Inhibition of autophagy as a new means of improving chemotherapy efficiency in high-LC3B triple-negative breast cancers. Autophagy. 2014;10:2122–2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Lazova R, Camp RL, Klump V, et al. Punctate LC3B expression is a common feature of solid tumors and associated with proliferation, metastasis and poor outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:370–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Peng Y-F, Shi Y-H, Shen Y-H, et al. Promoting colonization in metastatic HCC cells by modulation of autophagy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Zhang Y, Wang F, Han L, et al. GABARAPL1 negatively regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling by mediating Dvl2 degradation through the autophagy pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;27:503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Rho SB, Byun H-J, Kim B-R, et al. GABAA receptor-binding protein promotes sensitivity to apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1807–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Bell ES, Coelho PP, Ratcliffe CDH, et al. LC3C-Mediated Autophagy Selectively Regulates the Met RTK and HGF-Stimulated Migration and Invasion. Cell Rep. 2019;29:4053–4068.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Islam M, Sooro MA, Zhang P. Autophagic Regulation of p62 is Critical for Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2019 January22];19. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5983640/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Rodger CE, McWilliams TG, Ganley IG. Mammalian mitophagy – from in vitro molecules to in vivo models. Febs J. 2018;285:1185–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Schwarten M, Mohrlüder J, Ma P, et al. Nix directly binds to GABARAP: a possible crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5:690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Takamura A, Komatsu M, Hara T, et al. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes Dev. 2011;25:795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Shimi T, Butin-Israeli V, Adam SA, et al. The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2579–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Grassi G, Di Caprio G, Santangelo L, et al. Autophagy regulates hepatocyte identity and epithelial-to-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions promoting Snail degradation. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Zada S, Hwang JS, Ahmed M, et al. Control of the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Metastasis by Autophagy-Dependent SNAI1 Degradation. Cells. 2019;8:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Park SH, Kim B-R, Lee JH, et al. GABARBP down-regulates HIF-1α expression through the VEGFR-2 and PI3K/mTOR/4E-BP1 pathways. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1506–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Ran L, Hong T, Xiao X, et al. GABARAPL1 acts as a potential marker and promotes tumor proliferation and metastasis in triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:74519–74526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Su B, Zhang L, Liu S, et al. GABARAPL1 Promotes AR+ Prostate Cancer Growth by Increasing FL-AR/AR-V Transcription Activity and Nuclear Translocation. Front Oncol. [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2019 December13];9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6872515/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Martinez-Lopez N, Athonvarangkul D, Mishall P, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate ERK phosphorylation. Nat Commun. [Internet]. 2013. cited 2019 February6;4. Available from. ;. . : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3868163/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Gollob JA, Wilhelm S, Carter C, et al. Role of Raf Kinase in Cancer: therapeutic Potential of Targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK Signal Transduction Pathway. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:392–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Colecchia D, Strambi A, Sanzone S, et al. MAPK15/ERK8 stimulates autophagy by interacting with LC3 and GABARAP proteins. Autophagy. 2012;8:1724–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Colecchia D, Rossi M, Sasdelli F, et al. MAPK15 mediates BCR-ABL1-induced autophagy and regulates oncogene-dependent cell proliferation and tumor formation. Autophagy. 2015;11:1790–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Takehara A, Hosokawa M, Eguchi H, et al. γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Stimulates Pancreatic Cancer Growth through Overexpressing GABAA Receptor π Subunit. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9704–9712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Abdollahzadeh I, Schwarten M, Gensch T, et al. The Atg8 Family of Proteins—Modulating Shape and Functionality of Autophagic Membranes. Front Genet. [Internet]. 2017;8. Available from. ;. : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5581321/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]