Abstract

Objective

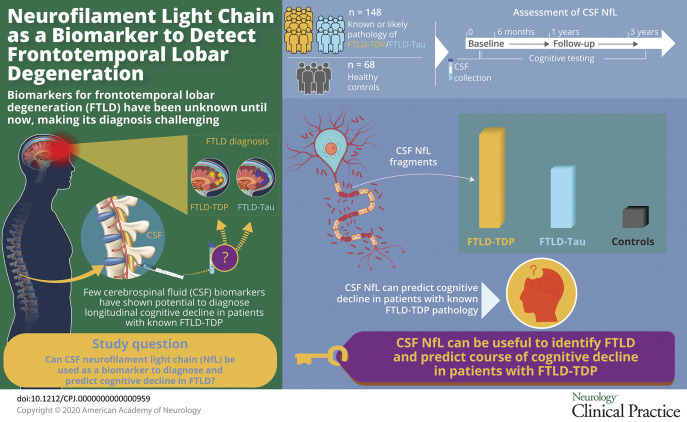

Accurate diagnosis and prognosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) during life is an urgent concern in the context of emerging disease-modifying treatment trials. Few CSF markers have been validated longitudinally in patients with known pathology, and we hypothesized that CSF neurofilament light chain (NfL) would be associated with longitudinal cognitive decline in patients with known FTLD-TAR DNA binding protein ~43kD (TDP) pathology.

Methods

This case-control study evaluated CSF NfL, total tau, phosphorylated tau, and β-amyloid1-42 in patients with known FTLD-tau or FTLD-TDP pathology (n = 50) and healthy controls (n = 65) and an extended cohort of clinically diagnosed patients with likely FTLD-tau or FTLD-TDP (n = 148). Regression analyses related CSF analytes to longitudinal cognitive decline (follow-up ∼1 year), controlling for demographic variables and core AD CSF analytes.

Results

In FTLD-TDP with known pathology, CSF NfL is significantly elevated compared with controls and significantly associated with longitudinal decline on specific executive and language measures, after controlling for age, disease duration, and core AD CSF analytes. Similar findings are found in the extended cohort, also including clinically identified likely FTLD-TDP. Although CSF NfL is elevated in FTLD-tau compared with controls, the association between NfL and longitudinal cognitive decline is limited to executive measures.

Conclusion

CSF NfL is associated with longitudinal clinical decline in relevant cognitive domains in patients with FTLD-TDP after controlling for demographic factors and core AD CSF analytes and may also be related to longitudinal decline in executive functioning in FTLD-tau.

Longitudinal pathology markers are urgently needed for patients with clinical frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) pathology, including FTLD-tau and FTLD-TAR DNA binding protein ~43kD (TDP).1,2 Clinical diagnosis of FTLD pathology has centered on CSF levels of phosphorylated tau (pTau), total tau (tTau), or β-amyloid1-42 (Aβ42) to exclude Alzheimer disease (AD).3,4 Although CSF pTau is correlated with cerebral tau burden in FTLD,5 diagnostic value of CSF pTau is limited. Elevated CSF neurofilament light chain (NfL), a neurofilament subunit released during axonal damage,6–8 is reported in known or likely FTLD-TDP9–12 and may be sensitive to likely FTLD-tau.13 Here, we examine whether CSF NfL assists FTLD pathology diagnosis beyond information from AD CSF markers.

FTLD-tau is often found in progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP),14 corticobasal degeneration,15,16 and nonfluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia (naPPA),17,18 and FTLD-TDP is associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (FTD-ALS)19 and semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA).17 An early study showed increased CSF NFL and normal tTau in clinically diagnosed FTD compared with high tTau but normal NFL in AD.20 A large study recently showed comparable CSF NfL in clinical behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), naPPA, and svPPA.21 Here, we examine usefulness of CSF NfL in diverse, clinically diagnosed FTD beyond that available from AD biomarkers.

The prognostic value of CSF pTau is unclear.4,9,22–24 Elevated baseline CSF NfL correlates with annualized brain atrophy rate and survival in FTD.4,11,13,22 Moreover, the optimal longitudinal clinical marker in diverse FTD phenotypes is unclear.21,23 Here, we relate CSF NfL to longitudinal clinical markers in patients who are clinically diagnosed or have known pathology.

Methods

Patients

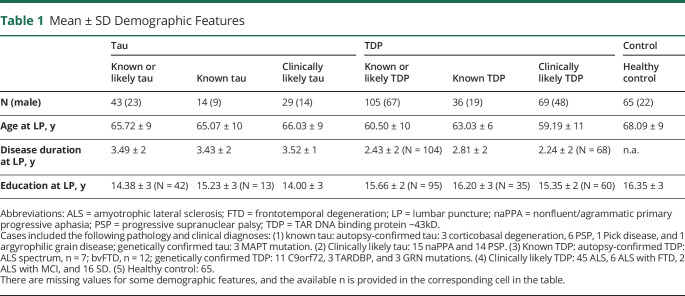

This study examined 213 patients and healthy controls recruited from 1997 to 2014 at a single site, Penn FTD Center. Among the 148 clinical cases with FTD spectrum clinical phenotypes were 30 autopsy-confirmed cases established on the basis of published methods,18,25,26 including 11 with primary tau pathology, 19 with primary TDP-43 pathology, and 20 genetic cases with known pathology established on the basis of published genotyping methods23 (table 1). Genetic and autopsy cohorts were merged into groups of patients with known FTLD-tau pathology (n = 14) or known FTLD-TDP pathology (n = 36). The remaining 98 of the 148 cases were FTD spectrum clinical phenotypes diagnosed with a sporadic disorder based on published criteria confirmed in a multidisciplinary consensus conference frequently associated with tau pathology, including naPPA (n = 15)17,24 and PSP (n = 14).25 There were also patients with a clinical diagnosis often associated with TDP-43 pathology, including ALS (n = 45),26 ALS with FTD (n = 8),27 and svPPA (n = 16).17,24 These groups were combined into likely tau (n = 29) or likely TDP (n = 69). We also studied 65 healthy controls. Clinically diagnosed patients had no evidence of other neurologic (e.g., vascular, trauma, surgery, and hydrocephalus), medical (e.g., inflammation, autoimmune, infection, and medication), or primary psychiatric (bipolar, major depression, and psychosis) conditions that can mimic FTD. Healthy controls were research volunteers without neurologic complaints and without risks for conditions that could have compromised cognitive, neurologic, or CSF factors, according to a self-completed survey. One control outlier was removed due to an NfL level >7 SD above the control mean. Some of these samples include CSF levels published previously as part of a larger cohort that are assessed here in a targeted manner with additional data.21

Table 1.

Mean ± SD Demographic Features

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and healthy controls using a process in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Pennsylvania.

Materials and Procedures

Cognitive testing was typically performed on the same day as CSF collection and always within about 6 months (mean ± SD = 47 ± 49 days, range = 0–178 days). Follow-up performance for longitudinal data was collected between 1 and 3 years after baseline (mean ± SD = 385 ± 101 days, range = 27–923 days). We obtained Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),28 an overall measure of cognitive impairment sampling a variety of cognitive domains for a total score of 30. Although developed initially for patients with Alzheimer disease, this measure has been shown to be sensitive to longitudinal decline in patients with FTD spectrum as well.29–31 We also obtained forward digit span,32 a measure of attention and short-term memory where patients repeat lengthier sequences of digits, and we note the longest correctly reproduced sequence; letter-guided category naming fluency (words beginning with the letter F),33 a measure of executive functioning where patients produce as many unique words as possible beginning with a target letter for 1 minute; visual confrontation naming using an abbreviated version of the Boston Naming Test34; and delayed word recall,35 a measure of episodic memory where patients are given 5 trials to learn 9 words, then an interference list, then immediate and delayed recall, and we report the number of correctly recalled words at a delay of 25 minutes.

Lumbar puncture (LP) was typically performed in the early AM following an overnight fast. CSF was collected into polypropylene collection tubes, frozen and stored at −80°C if not immediately analyzed within 1 hour, and analyzed without prior thaws, as previously described.36 CSF pTau, tTau, and Aβ42 were measured using the multiplex xMAP Luminex platform (Luminex Corp, Austin, TX) with the INNOBIA AlzBio3 kit (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium).37 NfL was measured with an ELISA method using 2 NfL mouse monoclonal antibodies (NfL21 as a capture antibody and NfL23 as a detector).38

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) tests were performed to test for differences in CSF NfL, pTau, tTau, and Aβ42 analyte levels between known or likely FTLD-tau, known or likely FTLD-TDP, known FTLD-tau, known FTLD-TDP, and healthy control groups. Similar analyses were performed to test for between-group differences for MMSE, Forward Digit Span, F word fluency, Boston Naming Test, and delayed word recall cognitive measures. We computed annualized neuropsychological difference scores by examining % change values to account for differing baseline performance and differing follow-up durations. Neuropsychological baseline was selected as the testing session closest to the date of CSF collection, and this was compared to follow-up performance for longitudinal data by calculating % change divided by the number of 12-month periods between tests. Spearman rank correlations were performed on the longitudinal data, relating demographic, CSF analyte, and cognitive data to NfL. Linear mixed-model regression analyses were performed on significant correlations between a CSF analyte and a cognitive measure to examine how the CSF analytes could predict the cognitive measures. Three models were used: model 1: NfL entered as the only predictor of a specific cognitive measure (cognitive measure ∼ NfL + error); model 2: NfL, age, and disease duration at the time of initial CSF sample entered as predictors of a specific cognitive measure because NfL measures may vary depending on age and disease duration39 (cognitive measure ∼ NfL + age + disease duration + error); and model 3: NfL, age, disease duration, pTau, tTau, and Aβ42 entered as predictors of a specific cognitive measure (cognitive measure ∼ NfL + age + disease duration + pTau + tTau + Aβ42 + error). All tests were 2 sided with a significance threshold of p ≤ 0.05.

Data Availability

Anonymized data will be shared by request with any qualified investigator with IRB approval for purposes of validation and/or replication using our center's established procedures for sharing data.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of patients and healthy controls are summarized in table 1. Demographics for the combined tau + TDP cohorts are summarized in table e-1 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A205). Groups were matched for age, education, and disease duration at the time of LP.

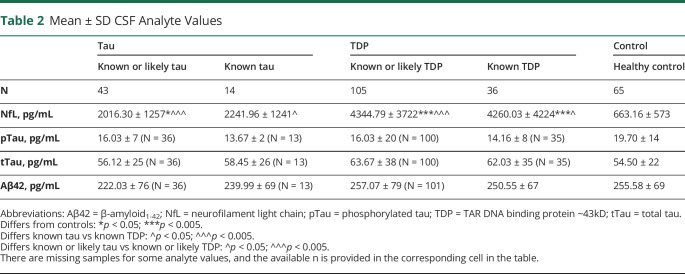

Comparisons of CSF Analyte Levels

CSF NfL, pTau, tTau, and Aβ42 levels in patients with known pathology or the extended cohort also including highly likely tau or TDP pathology and controls are summarized in table 2. Analyte levels for the combined tau + TDP cohorts are summarized in table e-2 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A205). CSF NfL levels were elevated in all groups relative to healthy controls, except for the known tau pathology group (where the level nevertheless was >3 times higher than controls). Moreover, patients with known TDP pathology had elevated CSF NfL levels relative to patients with known tau pathology, and patients with known or likely TDP pathology had elevated CSF NfL levels relative to patients with known or likely tau pathology. Although these findings were robust to age and other CSF analytes, ANCOVAs covarying for disease duration in the known pathology group resulted in nonsignificant, marginal NfL differences between groups, suggesting that disease duration decreases the diagnostic value of CSF NfL levels. In addition, further analyses performed after excluding all patients with ALS revealed elevated CSF NfL levels in each of the patient groups relative to healthy controls. However, there was no longer a significant difference between the tau and TDP pathology groups.

Table 2.

Mean ± SD CSF Analyte Values

ANCOVAs showed a difference in CSF pTau levels between FTLD-tau, FTLD-TDP, and healthy control groups, but no differences in pairwise comparisons or after removing patients with ALS. CSF tTau levels did not differ between groups. However, after patients with ALS were removed, patients with known or likely TDP pathology had higher CSF tTau levels than both patients with known or likely tau pathology and healthy controls. This result remained true after covarying for age and disease duration, but lost significance after covarying for other CSF analytes. Although the mean Aβ42 level was above our statistical threshold for likely AD pathology in all groups, it is noteworthy that the mean Aβ42 level of patients with known or likely FTLD-tau pathology was significantly lower compared with controls after controlling for age and other CSF analytes, suggesting the possibility of AD copathology in some patients with clinically diagnosed disease. This result remained true after the removal of patients with ALS. CSF NfL levels thus appear to be relatively more sensitive to the presence of FTD spectrum pathology than other CSF analytes, particularly in patients with FTLD-TDP, although the magnitude of the biomarker change depends in part on disease duration and the inclusion of patients with ALS.

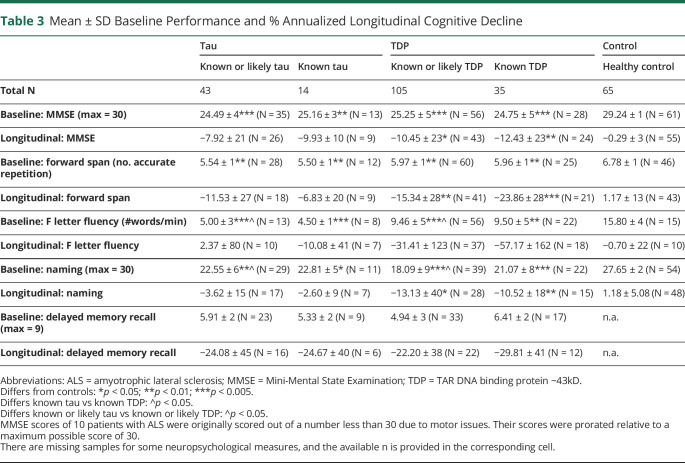

Comparisons of Cognitive Data

Baseline performance on cognitive measures and annualized % performance difference score are summarized in table 3. Cognitive data for the combined tau + TDP cohorts are summarized in table e-3 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A205). Baseline MMSE differed in each patient group compared with controls. Longitudinal MMSE decline differed from controls in patients with known TDP pathology and in the extended group of patients with known or likely TDP pathology. After removal of patients with ALS, these results remained consistent. Likewise, baseline forward digit span and naming differed in each of the patient groups compared with controls, and longitudinal decline in forward digit span and naming differed from controls in patients with known TDP pathology and the extended group of patients with known or likely TDP pathology. In addition, baseline naming was lower in patients with known or likely TDP pathology than patients with known or likely tau pathology. After the removal of patients with ALS, patients with known or likely TDP pathology had more longitudinal decline in naming than patients with known or likely tau pathology. Otherwise, results remained consistent. Baseline F letter fluency differed from controls for each of the patient groups, but did not differ from controls in longitudinal performance. Baseline F letter fluency was also lower in patients with known or likely tau pathology than known or likely TDP pathology before removal of patients with ALS. The results remained consistent after removal of patients with ALS. Performance for delayed memory did not differ between patient groups (delayed memory test results were not available in healthy controls) at baseline or longitudinally. However, after removal of patients with ALS, baseline delayed memory was lower in patients with known or likely TDP pathology than patients with known or likely tau pathology. Thus, MMSE, forward digit span, and naming appear to be relatively sensitive to longitudinal change in patients with TDP pathology.

Table 3.

Mean ± SD Baseline Performance and % Annualized Longitudinal Cognitive Decline

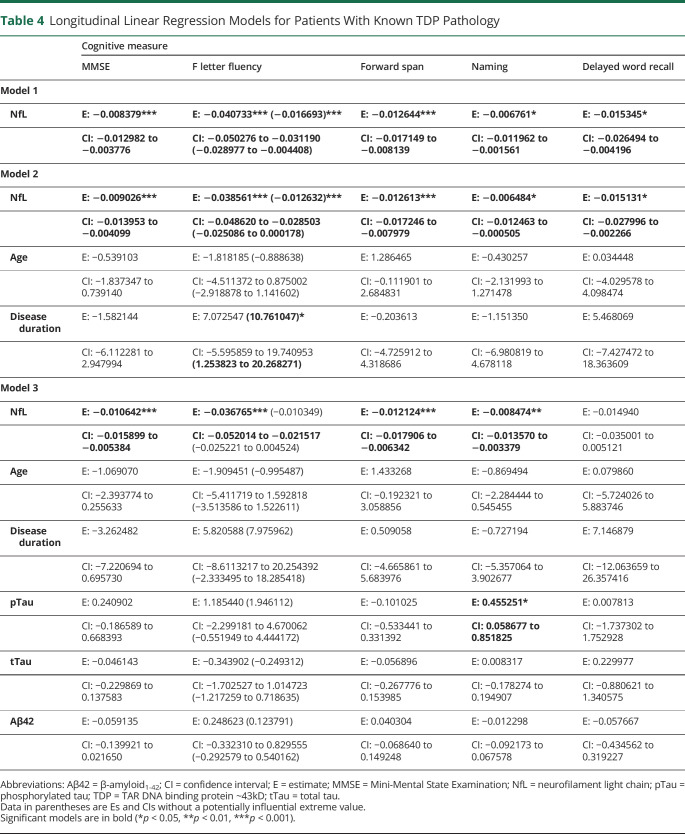

Regression Analyses With NfL as a Predictor of Longitudinal Cognitive Decline

Regression analyses were performed for significant correlations between CSF NfL levels and longitudinal cognitive values, controlling for demographic variables and other CSF analytes. Spearman rank correlations of CSF NfL levels with longitudinal cognitive data are summarized in table e-4 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A205). Regression analyses of the combined tau + TDP cohorts are summarized in table e-5.

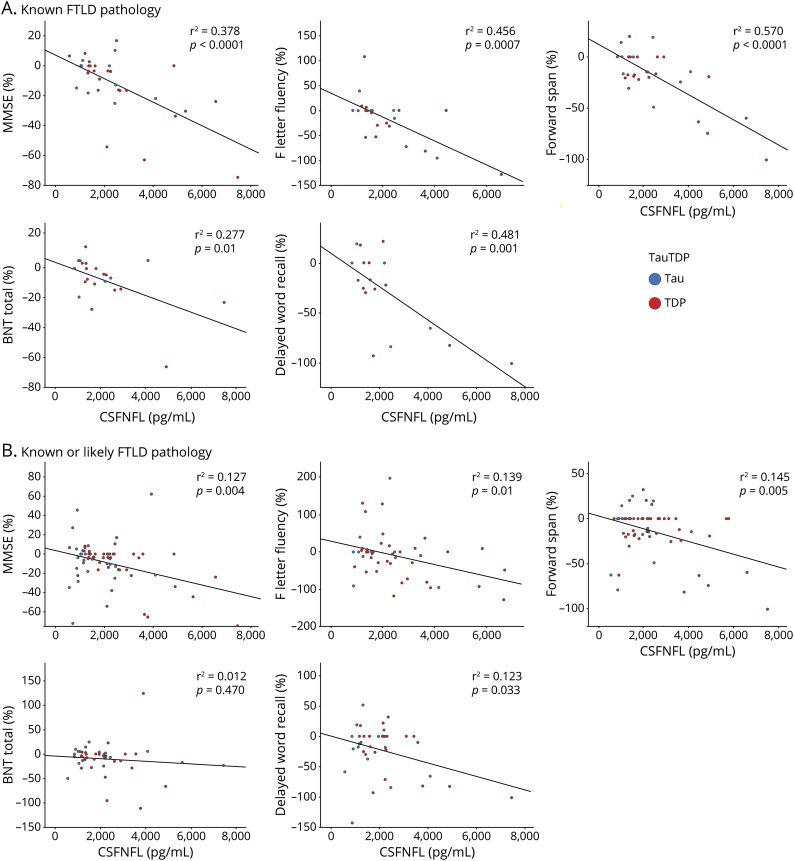

Patients With Known FTLD-TDP Pathology

Consider first the regressions involving patients with known TDP pathology (table 4 and figure). In patients with FTLD-TDP with known pathology, model 1 showed that elevated CSF NfL significantly predicted % annualized decline in MMSE scores. For model 2, which included age and disease duration as covariates, elevated CSF NfL significantly predicted % annualized decline in MMSE scores. For model 3, which included age, disease duration, and other CSF analytes as covariates, CSF NfL predicted % annualized decline in MMSE scores. For specific cognitive measures, elevated CSF NfL predicted % annualized decline in F letter fluency in model 1, model 2, and model 3. Models 1 and 2 were still significant after a potentially influential extreme value was removed, but model 3 was no longer significant after the extreme value was removed. Elevated CSF NfL also predicted % annualized decline in forward span in patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology for models 1, 2, and 3. Elevated CSF NfL predicted % annualized decline in naming in patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology for all 3 models as well, and pTau also contributed to this association in model 3. Last, elevated CSF NfL was able to predict % annualized decline in delayed word recall in patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology for model 1 and model 2. However, model 3 was not significant. Regression analyses for patients with FTLD-TDP pathology excluding those with ALS are summarized in table e-6 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A205). Results remained consistent for MMSE, F letter fluency, forward span, and delayed word recall. For naming, CSF NfL was able to predict longitudinal decline in models 1 and 3 in patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology only.

Table 4.

Longitudinal Linear Regression Models for Patients With Known TDP Pathology

Figure. Scatterplots Illustrating Relationships Between CSF NfL and Cognitive Measures in All Patients With FTLD With Known Pathology (Upper Row) and All Patients With FTD With Known or Likely Pathology (Lower Row).

R2 values and fit lines are those generated from standard linear regression using a least squares methods. Scatterplots showing the distribution of cognitive performance relative to CSF NfL level in patients with known FTLD pathology (A). Scatterplots showing the distribution of cognitive performance relative to CSF NfL level in patients with known or likely FTLD pathology (B). BNT = Boston Naming Test; CSFNFL = cerebrospinal fluid level of neurofilament light chain; FTD = frontotemporal degeneration; FTLD = frontotemporal lobar degeneration; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; NfL = neurofilament light chain; TDP = TAR DNA binding protein ~43kD.

Regression analyses for the extended group of patients with known or likely TDP pathology are summarized in table e-7 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A205). These analyses showed similar results to the patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology. However, CSF NfL was no longer able to predict longitudinal decline in naming, and CSF NfL was able to predict decline in delayed word recall in all models 1, 2, and 3.

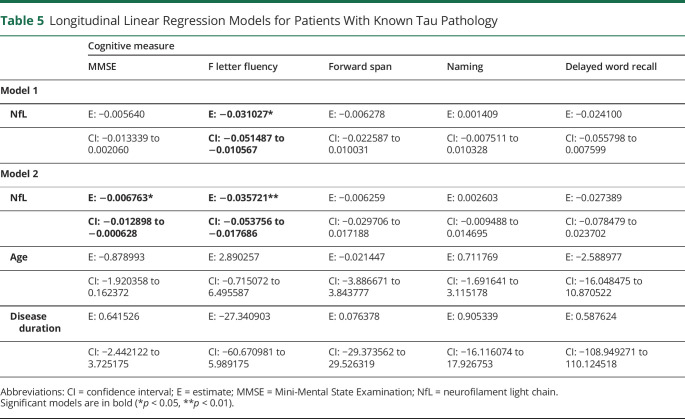

Patients With Known FTLD-tauPathology

Linear mixed-model analyses of patients with known FTLD-tau pathology are summarized in table 5 and figure. CSF NfL was able to predict MMSE decline in model 2 only. CSF NfL predicted F letter fluency decline in model 1 and model 2. In the extended group including known or likely FTLD-tau pathology, table e-8 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A205) shows in model 3 that CSF tTau was able to predict decline in forward span and episodic memory, and CSF Aβ42 was able to predict decline in word list recall.

Table 5.

Longitudinal Linear Regression Models for Patients With Known Tau Pathology

Discussion

Our findings indicate that CSF NfL levels are elevated in patients with FTD compared with controls, including patients with known FTLD-TDP or FTLD-tau pathology, and CSF NfL is elevated in patients with FTLD-TDP pathology compared with those with FTLD-tau pathology, although this may be confounded somewhat by disease duration and phenotype. Moreover, we find that CSF NfL can predict longitudinal cognitive decline in patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology in multiple cognitive domains, including executive function, language, and attention that are compromised in FTD, and these predictions remain statistically robust in patients with known pathology after controlling for demographic factors implicated in longitudinal analyses and core AD CSF analytes. This effect may also be evident in patients with FTLD-tau for executive measures. However, these findings appear to be attenuated in larger cohorts that include clinically defined patients, possibly due to the presence of secondary pathology. We discuss each of these findings below.

Assessments of CSF NfL reveal generally elevated levels in both FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP pathology groups compared with healthy controls. These results confirm previous findings in autopsy-confirmed FTLD.9–11,13,21 Previous work attempting to identify patients with FTLD pathology often depended on the use of core AD CSF analytes to show an absence of an AD profile (reduced Aβ42 and elevated pTau) in a clinically appropriate sample,3,36 and CSF NfL is elevated in autopsy-defined cases with FTLD compared with AD.21,40 Although we find here that CSF NfL is elevated in patients with FTLD pathology, these findings are confounded by disease duration. Others also showed that CSF NfL is correlated with disease duration,4,9,23,41 and this may reflect increasing axonal degeneration as neurodegeneration advances, although this is not a universal finding.11 Although age may be a confound in healthy controls,39 age does not confound CSF NfL in patients in this study, consistent with other findings,39 possibly due to the overwhelming effect of disease.

We find differences between FTLD pathology subgroups. Elevated CSF NfL is most robust in FTLD-TDP pathology, and CSF NfL remains elevated in patients with FTLD-TDP pathology compared with controls after excluding patients with ALS. Patients with FTLD-TDP pathology also have significantly elevated CSF NfL compared with FTLD-tau pathology, although the difference between FTLD-TDP and FTLD-tau is borderline after excluding patients with ALS. Direct comparisons of NfL levels in FTLD-TDP compared with FTLD-tau have been published in small cohorts,9 and our finding with a larger cohort replicates these results. Although a difference between FTLD-TDP and FTLD-tau was not found in some studies,4 this may have been related in part to the large proportion of mutation carriers in other studies. Although not as robust as in FTLD-TDP, CSF NfL is elevated in FTLD-tau pathology relative to healthy controls. These results are gathered from relatively small groups and require replication.

We examine the relationship between CSF NfL and cognitive decline in each pathologic cohort separately because of unclear claims about selective effects for NfL in FTLD-TDP or FTLD-tau. We find a robust pattern consistent with the claim that NfL can predict cognitive decline in patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology. Thus, CSF NfL in known FTLD-TDP pathology is able to predict declining performance on the MMSE. This remains true after considering age and disease duration. A correlation between core AD CSF analytes and CSF NfL has been reported.4 We show here that despite this correlation, CSF NfL can account for difference between patients with FTLD-TDP and controls, and between patients with FTLD-TDP and FTLD-tau, that are not otherwise explained by CSF levels of pTau, tTau, and Aβ42. Moreover, these findings are maintained after excluding patients with ALS. Although there is a common axonal source of tau and NfL, CSF tau and NfL may reflect different variants of axonal damage. Thus, there is added value to CSF NfL beyond that which can be derived from core AD CSF biomarkers.

Regression analyses relate CSF NfL to % cognitive decline in the combined cohort of all patients with FTLD with known pathology. However, we are unable to fully extend the longitudinal predictive capacity of CSF NfL to patients with known FTLD-tau pathology alone. After incorporating demographic factors, CSF NfL is associated with longitudinal decline of MMSE in known FTLD-tau pathology, but there are too few cases to assess the potential role of core CSF AD analytes in the FTLD-tau cohort. Additional work is needed to assess the role of core CSF AD analytes in a larger cohort of FTLD-tau cases.

It has been difficult to establish a gold standard for clinical progression in FTD. MMSE and Clinical Dementia Rating have been used most often to reflect overall clinical decline in FTD, although these measures were developed to reflect clinical difficulties in AD. Tracking clinical decline with these measures may be less than optimal in FTD where patients have primarily language, executive, and social disorders and less memory difficulty. Indeed, there is not uniform agreement on the clinical measures that should be collected during longitudinal clinical evaluation or used as end points during a treatment trial in FTD. In this study, we find that CSF NfL is associated with declining performance in other specific cognitive domains that are impaired in patients with known FTLD pathology. This includes executive functioning, attention and auditory-verbal short-term memory, language, and delayed episodic memory recall. Each of these cognitive measures is associated with somewhat distinct neurocognitive networks implicating different brain regions that are often compromised in FTD. Moreover, each of these associations in FTLD-TDP is robust to demographic factors such as age and disease duration and to CSF levels of core AD biomarkers. In FTLD-tau, however, we find that CSF NfL can predict decline in category naming fluency, but not in other specific cognitive measures. In FTLD-tau, there are insufficient data to examine the role of core CSF AD analytes, and additional work is needed to assess core CSF AD analytes in a larger group of patients with FTLD-tau pathology.

When we examine the usefulness of CSF NfL for predicting cognitive decline in a larger cohort including both pathologically and clinically defined cases with FTLD-TDP, we replicate findings of the cohort with known pathology only in part. Elevated CSF NfL is evident in the larger cohort that includes both patients with known pathology and those with clinically diagnosed disease. Moreover, NfL is associated with declining category naming fluency, forward digit span, and delayed memory recall, but these are generally less robust than in the cohort with known pathology, and longitudinal decline in naming is not significantly associated with NfL. In the tau cohort including both pathologically and clinically defined cases, we do not find any significant effects for NfL. These differences in clinically diagnosed patients compared with a cohort of known pathology in the present study may be due in part to the possibility that some clinically diagnosed patients may have secondary AD copathology, a finding in neurodegenerative disease that is not uncommon.41,42 In addition, some patients may have been misdiagnosed with FTLD, although the true underlying primary pathology is AD, another finding that is not uncommon in nonamnestic phenotypes with AD pathology that can resemble FTD.43–45 Some evidence consistent with these possibilities comes from the observation of an association of tTau and Aβ42 with longitudinal decline in episodic memory recall in the cohort of FTLD-tau cases including both known and clinically diagnosed disease. These observations emphasize the importance of studies in patients with known pathology, even in the setting of larger cohorts.

The basis for a more widespread and robust effect in FTLD-TDP than FTLD-tau is unclear. Although not statistically significant, FTLD-tau cases are 5 years older than FTLD-TDP cases, and LP is obtained following a longer disease duration in FTLD-tau than in FTLD-TDP. The TDP cohort also includes cases with ALS, a neurodegenerative condition with relatively rapid progression, and NfL is elevated in conditions of acute axonal degeneration,6–8 although exclusion of ALS cases does not substantially alter our findings in FTLD-TDP. Alternately, the finding of some predictive value of NfL for declining cognition in FTLD-TDP but not FTLD-tau may reflect that TDP-43 pathology has a greater effect on axonal degeneration than FTLD-tau. TDP-43 is implicated in modulation of neuronal inflammatory processes, and disturbances of these processes may evoke greater axonal degeneration in FTLD-TDP than FTLD-tau. Another possibility may be related in part to the smaller FTLD-tau cohort that has statistically less power to demonstrate an effect. Additional work is needed to assess these possibilities.

Recent work has shown a correlation between CSF NfL and serum or plasma NfL.11,46 It is attractive to study biomarkers in blood because of relatively easier access and perceived reduction in invasiveness compared with obtaining CSF. However, it may be useful to obtain multiple validated biomarkers simultaneously for differential diagnosis such as discriminating FTD from AD, and CSF may be a superior modality in this context because of persistent concerns associated with the robustness of blood measures of tau and Aβ42. Likewise, molecular radioligands using PET have been developed for core AD biomarkers of amyloid and tau, but PET radioligands are not available for NfL.

Strengths of this report include the focus on FTLD and the relatively large sample with known pathology. Moreover, we examine the relative contribution of core AD CSF biomarkers and relate these to longitudinal decline in multiple cognitive domains more relevant for FTD phenotypes. Nevertheless, some limitations should be kept in mind. Although we examine a relatively large cohort manifesting a rare disease, the cohorts are small, and additional work is needed with larger groups. Relatedly, there are insufficient numbers with each of the clinical diagnoses or subtypes of FTLD-TDP or FTLD-tau pathology to examine finer-grained interactions. We assess longitudinal measures that more closely reflect cognitive difficulties in FTD, but our range of available cognitive measures is limited and not every patient has every cognitive test. Future studies should examine additional cognitive measures and assess comparable patients with similar data from other sites.

With these caveats in mind, we find that CSF NfL distinguishes patients with known FTLD pathology from healthy controls, and patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology have elevated CSF NfL compared with patients with known FTLD-tau pathology, but the diagnostic value of CSF NfL alone is limited in part by the potentially confounding roles of disease duration and phenotype. Moreover, CSF NfL in patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology is associated with longitudinal decline on a range of cognitive measures, including those commonly compromised in patients with an FTD phenotype, but is associated only with declining executive measures in FTLD-tau. These findings are generally robust to demographic factors such as age and disease duration that may confound NfL and provide additional information beyond that available from core AD CSF biomarkers. We extend these analyses to a larger cohort incorporating patients with known pathology and clinically defined patients, but results may be less robust for some associations due to the possible presence of AD copathology.

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

This study was supported in part by the NIH (AG066597, AG017586, AG052943, AG054519, and AG010124).

Disclosure

J.V. Zhang has nothing to declare. D.J. Irwin received support from U19 AG062418, NS088341, and PO1 AG 017586. K. Blennow holds the Torsten Söderberg Professorship in Medicine at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and is supported by the Swedish Research Council (#2017-00915), the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (#AF-742881), Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2017-0243), and a grant (#ALFGBG-715986) from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the County Councils, the ALF agreement. H. Zetterberg is a Wallenberg Academy Fellow supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2018-02532), the European Research Council (#681712), and Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-720931). E.B. Lee received support from P30 AG010124 and U19 AG062418. L.M. Shaw received support from P30 AG010124, U01 AG024904, and U01 AG016976. K. Rascovsky received support from P30 AG010124, U19 AG062418, and PO1 AG 017586. L. Massimo received support from R00AG056054. C.T. McMillan received support from AG058732, AG066152, NS092091, and U19 AG062418. A. Chen-Plotkin is supported by the Parker Family Chair; she also received support from P30 AG010124 and U19 AG062418. L. Elman has nothing to declare. V.M.-Y. Lee is supported by the John H. Ware 3rd Professorship in Alzheimer's Research. She also received support from P30 AG010124, PO1 AG 017586, and U19 AG062418. L. McCluskey and J.B. Toledo have nothing to declare. D. Weintraub received support from U19 AG062418, Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, Alzheimer's Therapeutic Research Initiative (ATRI), Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS), and the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (IPMDS); honoraria for consultancy from Acadia, Aptinyx, Biogen, CHDI Foundation, Clintrex LLC, Enterin, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Ferring, Janssen, Promentis, Signant Health, Sage, Sunovion, and Takeda; and license fee payments from the University of Pennsylvania for the QUIP and QUIP-RS. D. Wolk received support from P30 AG010124. J.Q. Trojanowski is supported by the William Maul Measey-Truman G. Schnabel, Jr., M.D. Professorship of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology; he also received support from P30 AG010124, U19 AG062418, PO1 AG 017586, U01 AG024904, U01 AG04161, R01 NS094003, R01 AG054991, 19PABHI34580006, and Michael J. Fox Foundation Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative. M. Grossman received support from the NIH (AG017586, AG052943, AG010124, AG062418, AG054519 and AG066597), in-kind support from Avid and Life, participation in treatment trials sponsored by Biogen, Eisai, and Alector, editorial support from Neurology, the Samuel Newhouse Foundation, the Robinson Family Foundation, and the Wyncote Foundation. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ CSF neurofilament light chain (NfL) distinguishes patients with known frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) pathology from healthy controls.

→ Patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology have significantly higher CSF NfL than patients with known FTLD-tau pathology, although this may be confounded somewhat by disease duration and phenotype.

→ CSF NfL in patients with known FTLD-TDP pathology is associated with longitudinal decline on executive and language measures commonly compromised in patients with a frontotemporal degeneration.

→ These findings are generally robust to demographic factors such as age and disease duration that may confound NfL and provide additional information beyond that available from core Alzheimer disease CSF biomarkers.

References

- 1.Forman MS, Farmer J, Johnson JK, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Neurol 2006;59:952–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josephs KA, Hodges JR, Snowden JS, et al. Neuropathological background of phenotypical variability in frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol 2011;122:137–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lleó A, Irwin DJ, Illán-Gala I, et al. A 2-step cerebrospinal algorithm for the selection of frontotemporal lobar degeneration subtypes. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:738–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meeter LHH, Vijverberg EG, Del Campo M, et al. Clinical value of neurofilament and phospho-tau/tau ratio in the frontotemporal dementia spectrum. Neurology 2018;90:e1231–e1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irwin DJ, Lleó A, Xie SX, et al. Ante mortem cerebrospinal fluid tau levels correlate with postmortem tau pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann Neurol 2017;82:247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman PN, Cleveland DW, Griffin JW, Landes PW, Cowan NJ, Price DL. Neurofilament gene expression: a major determinant of axonal caliber. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987;84:3472–3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamasaki H, Itakura C, Mizutani M. Hereditary hypotrophic axonopathy with neurofilament deficiency in a mutant strain of the Japanese quail. Acta Neuropathol 1991;82:427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosengren LE, Karlsson JE, Karlsson JO, Persson LI, Wikkelsø C. Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other neurodegenerative diseases have increased levels of neurofilament protein in CSF. J Neurochem 1996;67:2013–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pijnenburg YA, Verwey NA, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, Teunissen CE. Discriminative and prognostic potential of cerebrospinal fluid phosphoTau/tau ratio and neurofilaments for frontotemporal dementia subtypes. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2015;1:505–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meeter LH, Kaat LD, Rohrer JD, Van Swieten JC. Imaging and fluid biomarkers in frontotemporal dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 2017;19:109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meeter LH, Dopper EG, Jiskoot LC, et al. Neurofilament light chain: a biomarker for genetic frontotemporal dementia. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2016;3:623–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teunissen CE, Elias N, Koel-Simmelink MJ, et al. Novel diagnostic cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for pathologic subtypes of frontotemporal dementia identified by proteomics. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2016;2:86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rojas JC, Karydas A, Bang J, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain predicts progression in progressive supranuclear palsy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2016;3:216–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Respondek G, Kurz C, Arzberger T, et al. Which ante mortem clinical features predict progressive supranuclear palsy pathology? Mov Disord 2017;32:995–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kouri N, Murray ME, Hassan A, et al. Neuropathological features of corticobasal degeneration presenting as corticobasal syndrome or Richardson syndrome. Brain 2011;134:3264–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray R, Neumann M, Forman MS, et al. Cognitive and motor assessment in autopsy-proven corticobasal degeneration. Neurology 2007;68:1274–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spinelli EG, Mandelli ML, Miller ZA, et al. Typical and atypical pathology in primary progressive aphasia variants. Ann Neurol 2017;81:430–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giannini LA, Xie SX, McMillan CT, et al. Divergent patterns of TDP-43 and tau pathologies in primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2019;85:630–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2006;314:130–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjögren M, Rosengren L, Minthon L, Davidsson P, Blennow K, Wallin A. Cytoskeleton proteins in CSF distinguish frontotemporal dementia from AD. Neurology 2000;54:1960–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsson B, Portelius E, Cullen NC, et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein levels with cognition in patients with dementia, motor neuron disease, and movement disorders. JAMA Neurol 2018;76:318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherling CS, Hall T, Berisha F, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament concentration reflects disease severity in frontotemporal degeneration. Ann Neurol 2014;75:116–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood EM, Falcone D, Suh E, et al. Development and validation of pedigree classification criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:1411–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 2011;76:1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Höglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: the movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 2017;32:853–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Mot Neuron Disord 2000;1:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strong MJ, Abrahams S, Goldstein LH, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2017;18:153–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grossman M, Libon DJ, Forman MS, et al. Distinct antemortem profiles in patients with pathologically defined frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1601–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Libon DJ, Xie SX, Wang X, et al. Neuropsychological decline in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a longitudinal analysis. Neuropsychology 2009;23:337–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiskoot LC, Panman JL, van Asseldonk L, et al. Longitudinal cognitive biomarkers predicting symptom onset in presymptomatic frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol 2018;129:3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV). San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodglass H, Kaplan E, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea & Fibiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Libon DJ, Mattson RE, Glosser G, et al. A nine-word dementia version of the California Verbal Learning Test. Clin Neuropsychol 2007;10:237–244. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Toledo JB, et al. Comparison of cerebrospinal fluid levels of tau and Aβ 1-42 in Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal degeneration using 2 analytical platforms. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1018–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol 2009;65:403–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaetani L, Höglund K, Parnetti L, et al. A new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for neurofilament light in cerebrospinal fluid: analytical validation and clinical evaluation. Alzheimers Res Ther 2018;10:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bridel C, van Wieringen WN, Zetterberg H, et al. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein in neurology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:1035–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alcolea D, Vilaplana E, Suárez-Calvet M, et al. CSF sAPPβ, YKL-40, and neurofilament light in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 2017;89:178–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toledo JB, Brettschneider J, Grossman M, et al. CSF biomarkers cutoffs: the importance of coincident neuropathological diseases. Acta Neuropathol 2012;124:23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson JL, Lee EB, Xie SX, et al. Neurodegenerative disease concomitant proteinopathies are prevalent, age-related and APOE4-associated. Brain 2018;141:2181–2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendez MF, Joshi A, Tassniyom K, Teng E, Shapira JS. Clinicopathologic differences among patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2013;80:561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mesulam MM, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Geula C, Bigio EH. Asymmetry and heterogeneity of Alzheimer's and frontotemporal pathology in primary progressive aphasia. Brain 2014;137:1176–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giannini LAA, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, et al. Clinical marker for Alzheimer disease pathology in logopenic primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 2017;88:2276–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinacker P, Anderl-Straub S, Diehl-Schmid J, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2018;91:e1390–e1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request with any qualified investigator with IRB approval for purposes of validation and/or replication using our center's established procedures for sharing data.