Abstract

It is imperative in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic that we serve our patients by implementing teleneurology visits for those who require neurologic advice but do not need to be seen face to face. The authors propose a thorough, practical, in-home, teleneurologic examination that can be completed without the assistance of an on-the-scene medical professional and can be tailored to the clinical question. We hope to assist trainees and practicing neurologists doing patient video visits for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on what can, rather than what cannot, be easily examined.

The current bedside neurologic examination originated in the late 1800s from the work of Wilhelm Erb, Joseph Babinski, and William Gowers and was refined by Gordon Holmes in the first half of the 1900s.1,2 Neurologists pride themselves on their bedside examination skills, and numerous books have been written on the topic.3–12 Specialists in diseases of the nervous system entered the telemedicine scene in the late 1990s with the advent of telestroke,13 but until recently, the broad application of telemedicine in other neurologic subspecialty areas has been limited.14

With the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, teleneurology has become essential to serve our patients while practicing physical distancing.15 Neurologists who had never performed video visits before started doing so in a matter of days, limiting face-to-face visits to patients with urgent (in the clinic) or emergent (in the emergency department or hospital) neurologic conditions. For nonurgent patients, the bedside, face-to-face examination became virtual seemingly overnight. This transition, an imperative during the COVID-19 pandemic, will likely continue to have a role even after physical distancing rules are relaxed.

Some articles have outlined the teleneurologic examination, and online videos discussing the topic have been produced.16–20 However, these often involved the neurologist viewing some parts of the examination completed by a medical professional present with the patient (a telepresenter), which has limited application when virtually examining patients within their homes.14,16,21–23 In this article, we first provide some general tips for video interactions and then outline a thorough teleneurologic examination. Having performed these maneuvers during in-home virtual visits, we focus on what can be easily examined, which can be tailored to the clinical question asked. It is a practical and therefore not exhaustive list, and individual practitioners will add their own favorite examination maneuvers. This teleneurologic examination does not replace the face-to-face examination, but as Voltaire said “the best is the enemy of the good,” and a good deal of information can be gleaned through a video interaction.

General Tips for Video Interactions

You will naturally look at the video image of the patient, as you should for observation purposes. However, be sure to occasionally look directly at the camera because that is the equivalent of making eye contact during a face-to-face visit.18 Tell the patient when you are going to look away to take notes or view the electronic health record, as otherwise they may think you are not paying attention to them.18 There may be an audio lag, so waiting a few seconds after the patient stops speaking before you begin to speak is also recommended. Patients should wear their hearing aids and glasses.

Overview of the Teleneurologic Examination

Maneuvers amenable to inclusion in a teleneurologic examination are listed below, grouping certain parts of the examination to minimize the number of times the patient has to change position or camera angles. Your personal examination might use a different order or only use certain components, based on the patient's presenting symptoms and time available for the video interaction. This approach is most relevant when there is not a medical professional assisting with the examination in the patient's home, which is the most common situation when doing outpatient teleneurology.

The gait, station, and motor examinations are limited by the degree of patient unsteadiness, the size of the patient room, how far the patient can get from the camera, the device/camera used by the patient, and the ability of the patient to adjust the angle of the camera. If the patient is alone during the video visit and has a history of falls with significant unsteadiness, it is best to avoid gait and Romberg testing. If the patient is sitting at a desk and connects via their desktop computer with a wall behind them, it will also be very difficult to see their entire body during the gait examination. Even then, many of the examination maneuvers described in this article can be performed.

Our appointment coordinators ask the patient to connect via desktop only if that is their sole option. If the patient connects via laptop, tablet, or smartphone, it is easier for the camera to be manipulated to show more of the gait, station, and motor examinations, if a family member or friend is also physically present to control the camera. Keep in mind that an additional companion may be needed to ensure patient safety while walking, if the patient is significantly unsteady.

If the virtual application being used to establish a video/audio connection allows the provider to share images or documents electronically with the patient, this may provide an alternative means to conduct portions of the neurologic examination outlined below. In those instances, the provider could forego using physical documents (e.g., printed images shown to the camera for mental status or language testing) to conduct the examination.

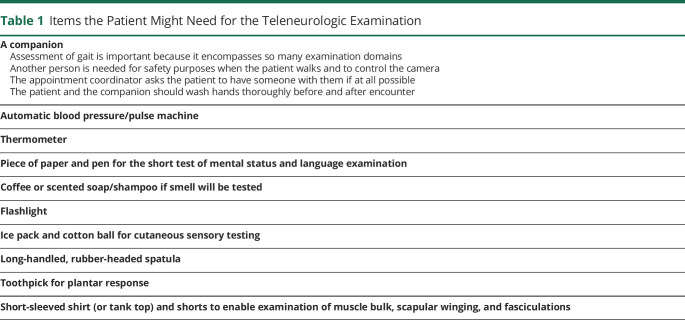

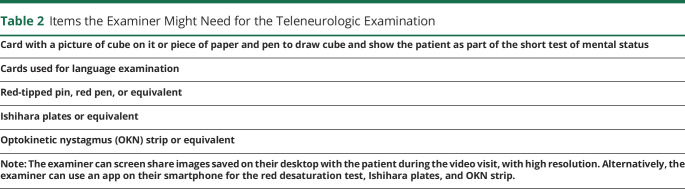

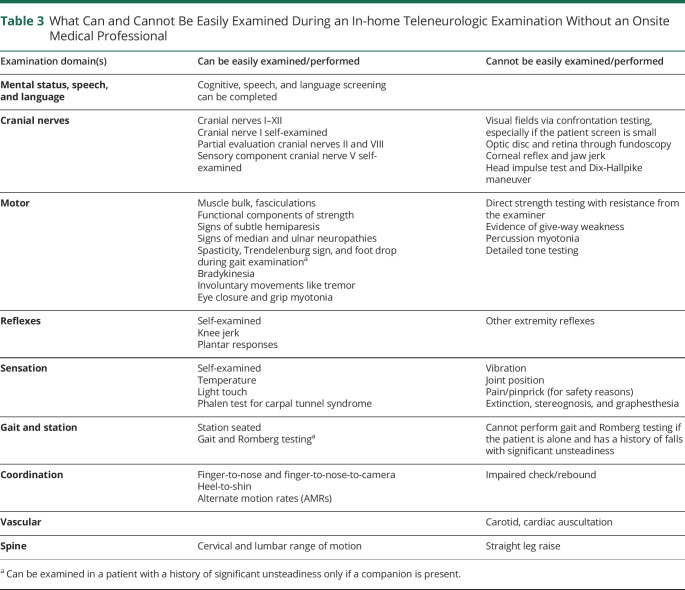

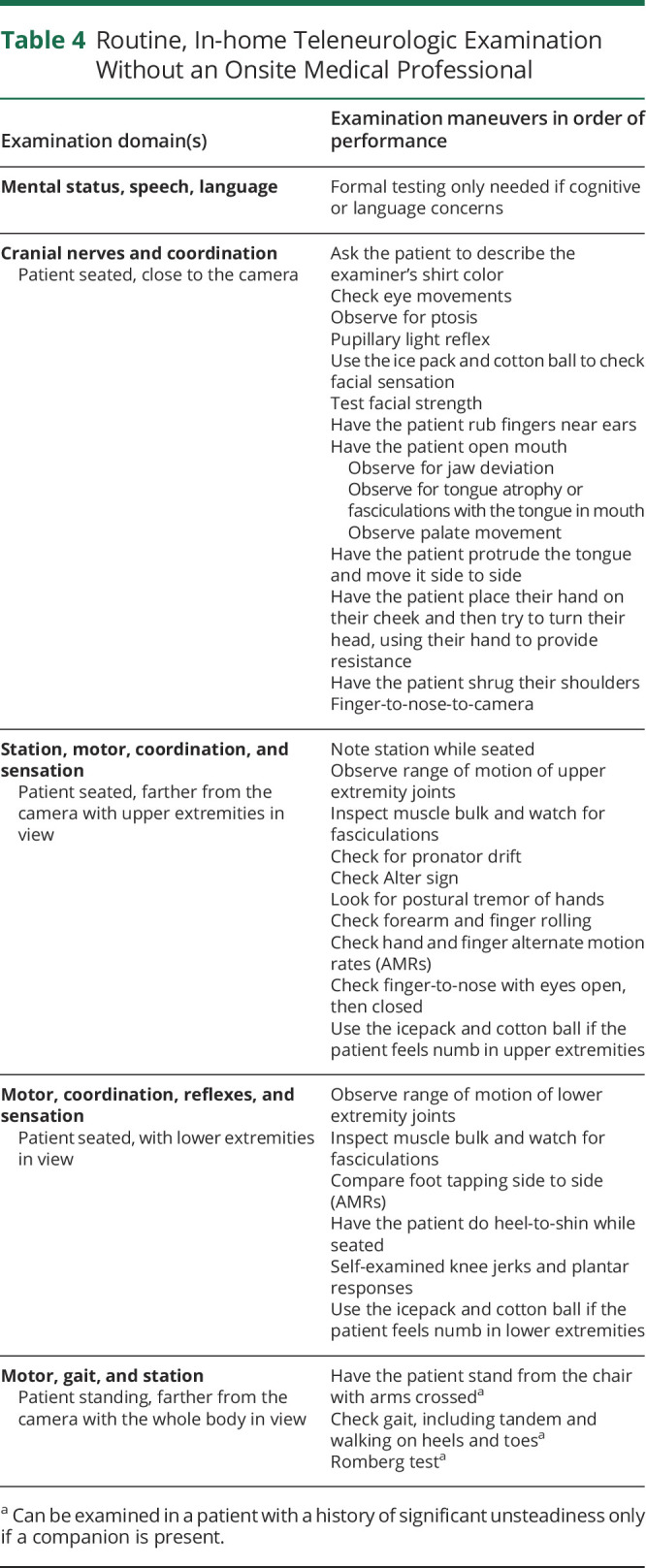

Table 1 lists items that the patient might need for the examination, and table 2 lists tools that the examiner might need. Table 3 summarizes the parts of the examination that can and cannot be easily completed during an in-home teleneurologic examination. Table 4 outlines a routine teleneurologic examination that includes some of the maneuvers described below and takes about 8–10 minutes to perform initially.

Table 1.

Items the Patient Might Need for the Teleneurologic Examination

Table 2.

Items the Examiner Might Need for the Teleneurologic Examination

Table 3.

What Can and Cannot Be Easily Examined During an In-home Teleneurologic Examination Without an Onsite Medical Professional

Table 4.

Routine, In-home Teleneurologic Examination Without an Onsite Medical Professional

The In-home Teleneurologic Examination

Vitals

• If available, have the patient use an automated blood pressure machine that also checks the heart rate

• Alternatively, have the patient check their radial pulse for 15 seconds

• Have the patient check temperature with a thermometer if available

Mental Status

• Perform the short test of mental status as described by Dr. Emre Kokmen24 or other standardized mental status test (Mini-Mental State Examination or Montreal Cognitive Assessment–Blind)18,19 Interpreting these tests requires knowledge of the patient's vision and hearing abilities and an understanding that this test administration is nonstandardized.25

• Hold any images required (e.g., cube drawing) to complete mental status testing directly up to the camera or share screen with the patient

• The patient will need a piece of paper and pen

• The patient will need to show the camera what they drew

Speech and Language

• Examine per usual.26 Show language examination cards to the camera or share the screen with the patient.

• The patient will need to show the camera what they wrote

Cranial Nerves

• Ask if they can smell coffee (whole beans or ground) or scented soap/shampoo. Check 1 nostril at a time by occluding the contralateral nostril.

• Find out what they can see out of one eye and then the other (e.g., have them describe your hair or shirt color and count fingers)

• The American Academy of Ophthalmology website has printable Snellen charts and instructions on how a patient can check their own visual acuity.27

-

• Check for visual neglect

○ Have the patient perform the line bisection test for visual neglect18

-

• Check for red desaturation in either eye with a red-tipped pin, red pen, or equivalent digital image

○ Compare red color in each eye, 1 eye at a time

• Check Ishihara plates in one eye and then the other (if worried about optic neuropathy)

-

• Spinning drum test/optokinetic nystagmus (OKN) strip

○ Hold the OKN strip or phone with OKN app toward the top of your image with lines moving to the left, allowing you to see the patient's OKN

○ Repeat with lines moving right, up, and down, looking for OKN in each direction

-

• Check eye movements, observe for nystagmus

○ Best to tell them to look left (then up and down) and look right (then up and down) rather than having the patient try to follow your finger because your finger will disappear off their screen

○ For saccades, have the patient keep their head still and look back and forth between the wall on their left and the wall on their right and then the ceiling and the floor. Encourage them to open their eyes widely, especially for vertical saccades.

○ Check convergence by having the patient look at their nose or hold a pen in front of their face and watch it as they slowly move it toward their nose

○ Have the patient fixate on the camera and rotate the head from side to side and then nod the head up and down

• Observe for ptosis

• For the pupillary light reflex, have the patient hold the flashlight under 1 eye, angled upward, so that you can still see their eye to observe for pupillary constriction. Repeat with the other eye. You can try having the patient close the other eye when checking the pupillary light response, but in doing, so many patients squint the eye you are interested in, which impairs your view of the pupil.

• Use ice pack and cotton ball for cranial nerve V sensory testing. Compare side to side in V1, V2, and V3 distributions.

• Have the patient open the mouth and look for jaw deviation. Look for masseter and temporalis atrophy by having them clench teeth.

• Test facial strength per usual (raise eyebrows, squeeze eyes shut, show teeth, and contract the platysma)

• Have the patient rub fingers near ears on either side or at least check if intact to voice (a confounder of the latter is that the examiner cannot know the volume adjustments made by the patient)

-

• Have the patient open the mouth and bring it close to the camera

○ Observe for tongue atrophy or fasciculations with the tongue in mouth. You might need the patient to shine the flashlight in their mouth to improve visualization.

○ Have the patient stick out the tongue a bit. Have the patient say “ahhh” quietly. Observe palate movement.

• Have the patient place their hand on their cheek and then try to turn their head, using their hand to provide resistance. Look for sternocleidomastoid contraction.

• Have the patient shrug their shoulders

• Have the patient extend arms in front with palms touching. If there is a unilateral spinal accessory nerve paralysis, the fingertips on the affected side extend beyond those on the healthy side because of shoulder drop.8 If the patient stands with hands at sides, the fingertips touch the thighs at a lower level than on the healthy side.8

• Have the patient protrude the tongue. Look for tongue deviation. Have them move the tongue side to side.

Motor, Gait, Station, Coordination, and Alternate Motion Rates/Rapid Alternating Movements (AMRs)

Seated Position, Farther From the Camera With Upper Extremities in View

• Note station while seated

• Observe range of motion of upper extremity joints, looking for muscle activation against gravity (for example, if they have wrist drop)

-

• Inspect muscle bulk and watch for fasciculations

○ Easier if the patient in short-sleeved shirt or tank top, latter if worried about shoulder girdle weakness or scapular winging

○ Oblique lighting may be used by the patient or companion to better see fasciculations

• Check for pronator drift

-

• Look for Alter sign (digiti quinti minimi sign) of mild hemiparesis28

○ Ask the patient to extend the arms and fingers forward with palms down

○ Sign consists of abduction of the little finger on the side of mild hemiparesis

○ If the fifth finger is abducted on both sides when arms are extended, the abduction has no clinical significance

○ This might be the only objective sign of hemiparesis, but usually other signs like flattening of the ipsilateral nasolabial fold are also present

○ Not seen with hemiplegia or profound hemiparesis28

• Look for postural tremor of hands with arms outstretched and when held in the chicken-wing position close to the face

-

• Check forearm, finger, and thumb rolling tests for subtle hemiparesis29

○ Five seconds in each direction

○ In the presence of a unilateral upper motor neuron lesion, the contralateral forearm/finger/thumb remains relatively stationary while the normal forearm/finger/thumb orbits around the affected forearm/finger/thumb

○ Studied in patients without spinal cord or peripheral nervous system lesions29

○ Sensitivity has varied in different studies, but in general, forearm and finger rolling are more likely to be abnormal than abnormal power, tone, and reflexes in a patient with a focal brain lesion29

○ The finger rolling test is more sensitive than forearm rolling.29 Thumb rolling may be more sensitive than index finger rolling to detect a subtle lesion of the cerebral corticospinal tract in patients with mild pure motor stroke affecting the upper limb.30

• Check hand and finger AMRs

• Have the patient squeeze one hand and look for mirror movement in the other. Repeat on the other side.

• Check finger-to-nose with eyes open and then closed

-

• Check finger-to-nose-to-camera (have the patient aim for the circle that houses the camera lens; you can tell if they miss the target as their image will not be blocked out fully)

○ Look for kinetic and/or terminal tremor

Seated Position, With Lower Extremities in View

• Observe range of motion of lower extremity joints, looking for muscle activation against gravity (for example, if they have foot drop)

• Inspect muscle bulk and watch for fasciculations (if the patient in shorts)

-

• Compare foot tapping (AMRs) side to side.

○ In 1 study comparing plantar response with foot tapping to detect an upper motor neuron lesion, Babinski testing had a sensitivity of 35% and a specificity of 77%, whereas foot tapping was found to be more reliable, with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 84%31

• Have the patient do heel-to-shin while seated

Standing Position, Farther From the Camera With the Whole Body in View

-

• Have the patient stand from the chair with arms crossed (looking for proximal lower extremity weakness)

○ If no concerns about significant unsteadiness and the patient alone, they will need to adjust the angle of their camera so that their whole body is in view

○ If the companion is present, they can run the camera and/or accompany the unsteady patient to ensure safe ambulation

-

• Check gait as usual, including tandem and walking on heels and toes

○ It is ideal to watch the patient walking to and from the camera in a hallway, but that may not be possible

○ Heel and toe walking can enable inspection of muscle bulk in the anterior and posterior leg compartments if the patient is wearing shorts and camera angle allows

○ Gait testing is the main way to look for spasticity during the teleneurologic examination

-

• Check the Romberg test

Other Motor Examination Maneuvers for Some Patients, Based on History

-

• Look for the Froment sign of ulnar neuropathy8

○ The patient uses the flexor pollicis longus primarily instead of the adductor pollicis to keep a piece of paper held tightly between their thumb and index finger32

-

• Look for the Wartenberg sign of ulnar neuropathy8

○ Also called abduction position of the little finger

○ Ask the patient to hold hands in front, palms forward, and fingers extended (like when stopping an oncoming vehicle)

○ Tell the patient to keep fingers together without exerting any force

○ The little finger (and sometimes ring finger) shows a tendency to abduct on the affected side8,32

-

• Look for the Wartenberg sign of median neuropathy8

○ Ask the patient to hold hands in front of them, palms out, making a diamond between the index fingers and thumbs (as when catching an American football thrown at one's head)

○ Usually the tips of the index fingers and thumbs touch each other

○ In a unilateral median neuropathy, there can be thumb abduction weakness, so the thumbs do not touch. The thumb on the affected side remains above (higher than) the thumb on the healthy side.8

-

• Do the Phalen test for carpal tunnel syndrome (not a motor test but fits best here)32

○ Have the patient press the dorsum of both hands together for 1 minute

○ Test is positive when paresthesias in a median nerve distribution are produced

-

• Do the pinch test for anterior interosseous neuropathy

○ A patient with an anterior interosseous neuropathy cannot form an “O” with the index finger and thumb due to weakness of the flexor pollicis longus and the radial flexor digitorum profundus33,34

○ The pinch test is positive when patients cannot give the “OK” sign and instead demonstrate apposition of the pads of the finger and thumb related to this pattern of weakness33,34

-

• Look for the Trendelenburg sign when the patient walks away from you

○ If the left hip abductors are weak, the pelvis will tilt to the right during the swing phase32

• Have the patient stand or hop on one leg and then the other (if no safety concerns)

• Have the patient perform 1 or more squats (if no safety concerns)

• Look for paradoxical abdominal movements during deep breathing in the supine position (if worried about respiratory muscle weakness)

• Lower extremity drift can be checked with the patient either on their back or stomach with knees flexed.12 Patient and camera positioning for this is difficult unless a family member/friend is running the camera.

• Look for eye closure and grip myotonia

-

• If worried about myasthenia gravis:

○ Have the patient hold their arms outstretched for 1–2 minutes while you are talking to them. The arms will start to drop if there is limb involvement.

○ Have the patient perform sustained upgaze after you have checked eye movements. Look for fatigable ptosis.

○ Perform an ice pack test

○ If the patient can feasibly lie down, test neck flexor strength and fatigability by having them lift their neck from the bed several times and holding it against gravity for 5 to 10 seconds

Reflexes

• Have the patient use the side of their hand or a long-handled, rubber-headed spatula to check their knee jerks. You will need to demonstrate the maneuver. The patient can try to elicit their own knee jerks with their feet on the ground or with their legs crossed. Instruct the patient to hold the spatula at the end of the handle and then strike below the patella with the edge/side of the spatula.35 Interpret with caution. Inadequate relaxation may prevent a reflex from being manifested.3 Anticipation or a predisposition toward exaggerated startle may result in the mistaken impression of a brisk reflex.3 Some examiners are skilled enough to have their patients check biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, and gastrocnemius reflexes during video visits.36

• The patient can check their own plantar response (both Babinski and Chaddock signs) with a toothpick. Have the patient grab their foot and put it on their knee. They should hold the toothpick between their thumb and index finger and then scrape in the usual “J” shape to try to elicit the Babinski sign, starting at the lateral heel. Patients often have little withdrawal when checking their own plantar responses. The patient can then perform the Chaddock maneuver along the lateral side of the foot.37,38

Sensory

• This is a challenging examination, but you can ask the patient to show you where they feel numb and then use an icepack and cotton ball to check small- and large-fiber modalities. Safety pins or similar sharp objects should be avoided or used with caution due to risk of inadvertent injury.

• Look for parietal or thalamic updrift of upper extremity contralateral to lesion12

• Look for pseudoathetosis of outstretched hands, which is seen in severe proprioceptive loss

• The Romberg test was checked during station examination

Other

-

• Observe for rest tremor

○ Have the patient rest hands on lap, close eyes, and state months in reverse order starting with December (you can also watch for rest tremor during gait examination)

• Observe for generalized bradykinesia

• Assess cervical range of motion

• Assess lumbar range of motion

• Comment on kyphosis and scoliosis

• Apraxia testing (ask the patient to salute and act out using a comb or hammering a nail)

Conclusion

It is imperative during the COVID-19 pandemic that we continue to serve our patients. We can do this by implementing teleneurology visits. This article outlines how a relatively complete neurologic examination can be performed, with some limitations, via video in a patient's home without the assistance of an onsite medical professional. Preparation on the part of the patient and the examiner is necessary, and ensuring patient safety during gait, station, and motor testing is paramount. Establishing competence in the teleneurologic examination will be important, as virtual care is likely to become more commonplace in the post–COVID-19 era.

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Study Funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.McHenry LC. Garrison's History of Neurology. Springfield: Thomas; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boes CJ. The history of examination of reflexes. J Neurol 2014;261:2264–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeJong RN. The Neurologic Examination, Incorporating the Fundamentals of Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology. New York: Hoeber; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monrad-Krohn GH. The Clinical Examination of the Nervous System. London: H. K. Lewis & Co.; 1921. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monrad-Krohn GH, Refsum S. The Clinical Examination of the Nervous System, 12th ed. London: Lewis; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denny-Brown D. Handbook of Neurological Examination and Case Recording. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes G. Introduction to Clinical Neurology. Edinburgh: Livingstone; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wartenberg R. Diagnostic Tests in Neurology: A Selection for Office Use. Chicago: Year Book Pub.; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayo Clinic Sections of Neurology and Section of Physiology. Clinical Examinations in Neurology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKendree CA. Neurological Examination: An Exposition of Tests with Interpretation of Signs and Symptoms. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis SL. Field Guide to the Neurologic Examination. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartzman RJ. Neurologic Examination. Malden: Blackwell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wechsler LR. Advantages and limitations of teleneurology. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatcher-Martin JM, Adams JL, Anderson ER, et al. Telemedicine in neurology: Telemedicine Work Group of the American Academy of Neurology update. Neurology 2020;94:30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein BC, Busis NA. COVID-19 is catalyzing the adoption of teleneurology. Neurology 2020;94:903–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govindarajan R, Anderson ER, Hesselbrock RR, et al. Developing an outline for teleneurology curriculum: AAN Telemedicine Work Group recommendations. Neurology 2017;89:951–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Neurology Telemedicine and COVID-19 Implementation Guide. Available at: aan.com/tools-and-resources/practicing-neurologists-administrators/telemedicine-and-remote-care/. Accessed April 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robblee J. Conducting a telemedicine neurologic exam. American Headache Society video. Available at: americanheadachesociety.org/covid-19-resources/. Accessed April 4, 2020.

- 19.Benameur K. American Academy of Neurology telemedicine and COVID-19 webinar. Available at: aan.com/tools-and-resources/practicing-neurologists-administrators/telemedicine-and-remote-care/. Accessed April 4, 2020.

- 20.Duvall J. Telehealth in the headache clinic. American Headache Society video. Available at: americanheadachesociety.org/covid-19-resources/. Accessed April 4, 2020.

- 21.Craig JJ, McConville JP, Patterson VH, Wootton R. Neurological examination is possible using telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare 1999;5:177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane RL, Bever CT, Ehrmantraut M, Forte A, Culpepper WJ, Wallin MT. Teleneurology in patients with multiple sclerosis: EDSS ratings derived remotely and from hands-on examination. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awadallah M, Janssen F, Korber B, Breuer L, Scibor M, Handschu R. Telemedicine in general neurology: interrater reliability of clinical neurological examination via audio-visual telemedicine. Eur Neurol 2018;80:289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kokmen E, Naessens JM, Offord KP. A short test of mental status: description and preliminary results. Mayo Clin Proc 1987;62:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips NA, Chertkow H, Pichora-Fuller MK, Wittich W. Special issues on using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for telemedicine assessment during COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:942–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayo Clinic Department of Neurology. Clinical Examinations in Neurology, 7th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Home Eye Test for Children and Adults. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Available at: aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/home-eye-test-children-adults. Accessed April 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alter M. The digiti quinti sign of mild hemiparesis. Neurology 1973;23:503–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson NE. The forearm and finger rolling tests. Pract Neurol 2010;10:39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nowak DA. The thumb rolling test: a novel variant of the forearm rolling test. Can J Neurol Sci 2011;38:129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller TM, Johnston SC. Should the Babinski sign be part of the routine neurologic examination? Neurology 2005;65:1165–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell WW. DeJong's the Neurologic Examination, 6th ed Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spinner M. The anterior interosseous-nerve syndrome, with special attention to its variations. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:84–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aljawder A, Faqi MK, Mohamed A, Alkhalifa F. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome diagnosis and intraoperative findings: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;21:44–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tweet by Jonathan Smith @jknuthsmith, 3/26/2020, 10:35 AM. Twitter. Accessed April 4, 2020.

- 36.Busis N. Special report: Neil Busis and Brad Klein make teleneurology easy & fun-tips for billing and physical exams. Neurology podcast. Available at: neurology.org/podcast. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 37.Sohrab SA, Gelb D. Value of self-induced plantar reflex in distinguishing Babinski from withdrawal. Neurology 2016;86:977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller Fisher C. Plantar reflex: elicitation by the patient. Trans Am Neurol Assoc 1973;98:262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]