Abstract

Objective

To characterize the breadth of neurologic findings associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in a diverse group of inpatients at an urban, safety-net US medical center.

Methods

Patients were identified through an electronic medical record review from April 15, 2020, until July 1, 2020, at a large safety-net hospital in Boston, MA, caring primarily for underserved, low-income, and elderly patients. All hospitalized adult patients with positive nasopharyngeal swab or respiratory PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 during their hospitalization or in the 30 days before admission who received an inpatient neurologic or neurocritical care consultation or admission during the study period were enrolled.

Results

Seventy-four patients were identified (42/57% male, median age 64 years). The majority of patients self-identified as Black or African American (38, 51%). The most common neurologic symptoms at presentation to the hospital included altered mental status (39, 53%), fatigue (18, 24%), and headache (18, 18%). Fifteen patients had ischemic strokes (20%). There were 10 in-hospital mortalities, with moderately severe disability among survivors at discharge (14%, median modified Rankin Scale score of 4).

Conclusions

Neurologic findings spanned inflammatory, vascular pathologies, sequelae of critical illness and metabolic derangements, possible direct involvement of the nervous system by SARS-CoV-2, and exacerbation of underlying neurologic conditions, highlighting a broad range of possible etiologies of neurologic complications in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Further studies are needed to characterize the infectious and postinfectious neurologic complications of COVID-19 in diverse patient populations.

Since the first reported cases of pneumonia in December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has rapidly become recognized as a multisystem illness, with known effects on virtually every organ system.1 Neurologic manifestations of COVID-19 are broad and may include seizures,2–4 movement disorders,5,6 peripheral neuropathies,7,8 cerebrovascular events,9–12 meningoencephalitis,13,14 posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome,15–17 and other encephalopathies.18–20 These complications may result from direct invasion of the CNS by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), as postinfectious complications, or as a result of critical illness and systemic infection.21,22

Although multiple case series have reported on individual neurologic complications such as ischemic stroke in small groups of patients with COVID-19,9,10 few have described the broad spectrum of neurologic disease across a large cohort of infected patients.22–25 Despite clear findings documenting the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 among both socioeconomically disadvantaged and racial and ethnic minority patient populations,26,27 few prior studies have characterized the full spectrum of neurologic complications of COVID-19 in a racially or socioeconomically diverse patient population. Here, we describe the breadth of neurologic findings associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a diverse group of inpatients at an urban, safety-net US academic medical center.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study protocol was approved by the Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board, which waived participant consent given that this observational study was found to represent no more than minimal risk of harm.

Setting

This study was conducted on the inpatient services of Boston Medical Center (BMC), an academic safety-net medical center in Boston, MA. As the largest safety-net hospital in New England, over half of BMC's patients come from households making no more than $25,000 annually, two-thirds identify as racial and/or ethnic minorities, and over one-third are born outside of the United States. Seventy-two percent of BMC's patient visits are made by underserved low-income and elderly patients who rely on government payors for insurance coverage.28 These government payors include both federal programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid, and state-specific programs, including Massachusetts' Health Safety Net program, which provides coverage for low-income individuals who are uninsured, underinsured, or ineligible for other insurance options because of their immigration status, and MassHealth, a Medicaid program that covers Massachusetts residents living at or below the federal poverty line, with special accommodations for pregnant women, minor children and their families, and individuals with chronic illnesses or disabilities. During the study period, Massachusetts was third among US states for both overall number of cases of COVID-19 and cases per capita, and BMC carried the second-highest COVID-19 caseload in the state.29

Patient Identification

Patients were identified through a prospective review of the electronic medical record from April 15, 2020, until July 1, 2020. The study period was chosen based on the peak of new cases in the state of Massachusetts.30 All hospitalized patients with positive nasopharyngeal swab or respiratory PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 during their hospitalization or in the 30 days before admission were eligible for inclusion. Those who received either (1) an inpatient neurologic or neurocritical care admission or (2) an inpatient neurologic or neurocritical care consultation at any time during the study period were included in the analysis.

Data Collection and Variables

Admission, hospitalization, and discharge variables were prospectively collected through a censoring date of July 1, 2020. Variables of interest included demographic data, prior medical and neurologic history, presenting symptoms, disease severity, medications administered, imaging and electrographic findings, laboratory data, and clinical status. Final neurologic diagnoses were determined through a secondary review of the electronic medical records by a study neurologist. Stroke etiology was determined by a study stroke neurologist using the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment classification system.31 MRI obtained during the hospitalization was reviewed by a study neurologist for acute abnormalities. Clinical status was determined at the time of discharge, including in-hospital mortality. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores were estimated for survivors before admission and at the time of discharge through review of the medical record by a study neurologist.

Data Analysis

All analyses were completed using Microsoft Excel. Patient characteristics were summarized by expressing categorical variables as counts and proportions and continuous variables as medians.

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

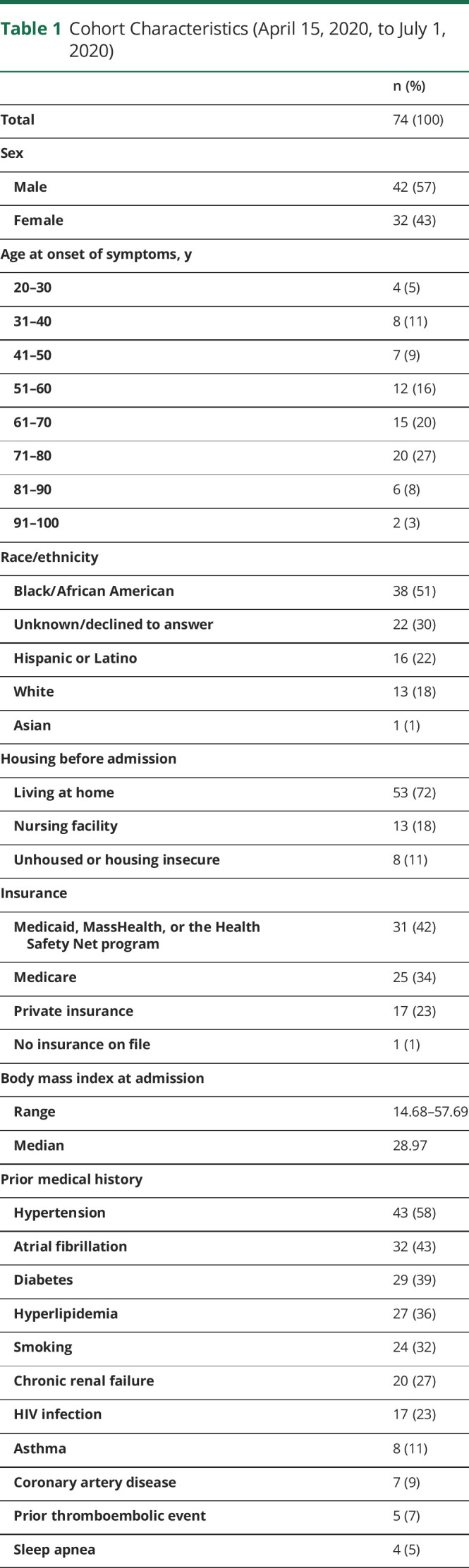

Nine hundred twenty-one adult patients were hospitalized with positive SARS-CoV-2 testing during the study period, of whom 74 had both positive SARS-CoV-2 testing and an inpatient neurologic or neurocritical care consultation or admission (42 male, 57%) with a median age of 64 years at the time of hospitalization (range 23–94 years) (table 1). The majority of patients self-identified as Black or African American (38, 51%) and 16 as Hispanic or Latino (22%). Most patients were living at home before admission (58, 72%), with 8 who self-identified as unhoused or housing insecure before admission (11%) and 13 admitted from a nursing facility (18%). The majority of patients used public insurance options, including Medicare (25, 34%) and Medicaid, MassHealth, or the Health Safety Net program (31, 42%). Medical history included vascular risk factors such as hypertension (43, 58%), atrial fibrillation (32, 43%), diabetes (29, 39%), and hyperlipidemia (27, 36%). Twenty patients had chronic kidney disease, including end-stage renal disease (27%).

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics (April 15, 2020, to July 1, 2020)

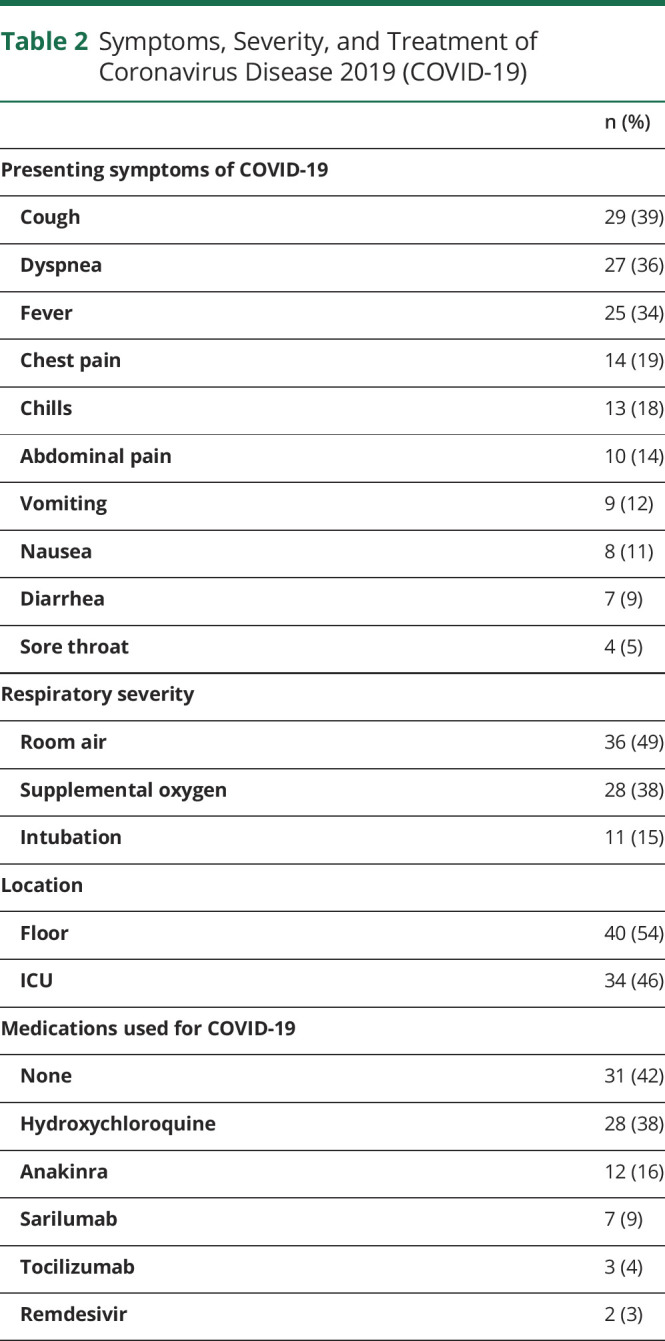

Clinical Data Associated With COVID-19

The most common symptoms of COVID-19 on hospital presentation in our cohort were cough (29, 39%), dyspnea (27, 36%), and fever (25, 34%) (table 2). Eleven patients required intubation (15%), whereas 28 required some form of supplemental oxygen (38%). Thirty-four patients required intensive care (46%). Medications used to treat COVID-19 included hydroxychloroquine (28, 38%), anakinra (12, 16%), sarilumab (7, 9%), tocilizumab (3, 4%), and remdesivir (2, 3%).

Table 2.

Symptoms, Severity, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

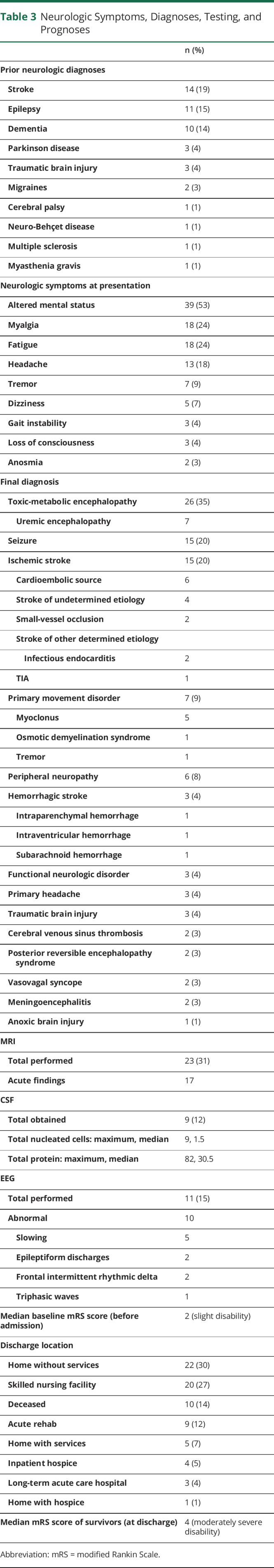

Neurologic Symptoms and Diagnoses

Neurologic diagnoses before admission included stroke (14, 19%), dementia (10, 14%), and epilepsy (11, 15%) (table 3). The most common neurologic symptoms at presentation to the hospital included altered mental status (39, 53%), myalgia (13, 24%), fatigue (18, 24%), and headache (18, 18%). Multifactorial or toxic-metabolic encephalopathy was the most common diagnosis (26 patients, 35%). Fourteen patients had ischemic strokes (19%), including 6 from a cardioembolic source, 2 from small vessel occlusion, 4 strokes of undetermined etiology, and 2 strokes of other determined etiology in patients with known infectious endocarditis. One patient had a TIA or aborted stroke following thrombolysis. Seven patients had primary movement disorders (9%), including 5 with myoclonus and 1 with osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Table 3.

Neurologic Symptoms, Diagnoses, Testing, and Prognoses

Imaging Findings

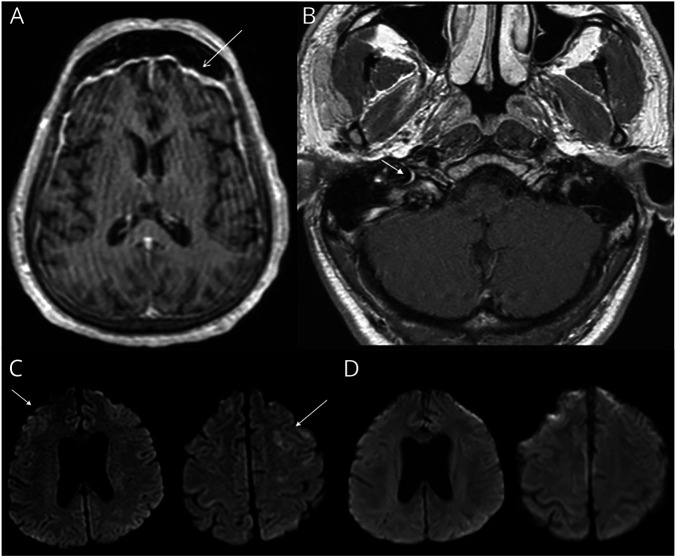

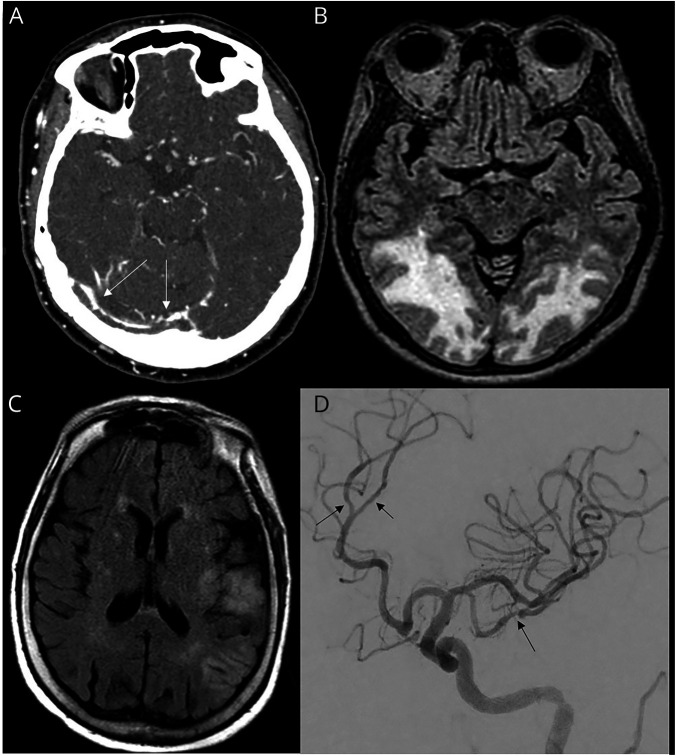

Head CT was obtained in 33 cases (45%). Brain MRI was obtained in 25 cases (31%) and revealed acute abnormalities in 17 cases, including ischemic stroke in 7, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in 2, and intracranial hemorrhage in 3. In 3 cases, imaging was suggestive of parainfectious inflammatory pathology (figure 1), including facial nerve enhancement in a patient who presented with bifacial nerve palsies, extensive T2-weighted changes in a patient with underling neuro-Behçet disease and concern for flare secondary to COVID-19, and T2-weighted parenchymal changes and overlying leptomeningeal enhancement in a patient with seizures and concern for a parainfectious autoimmune encephalitis with improvement on subsequent imaging following corticosteroid administration. In 1 case, MRI revealed changes consistent with anoxic brain injury following cardiac arrest, and in 2 cases, MRI revealed changes consistent with posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome in critically ill patients (figure 2). The final case revealed extensive T2-weighted changes in a patient with underlying HIV infection and confirmed cryptococcal meningoencephalitis.

Figure 1. Range of Inflammatory Imaging Findings in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019.

(A) Postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI sequences demonstrate diffuse smooth pachymeningeal thickening and enhancement most prominent in the frontal and temporal lobes. (B) Postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI sequences reveal asymmetric enhancement of the labyrinthine segment and genu of the right facial nerve. (C) T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI sequences demonstrate hyperintensity of the bilateral frontal lobes that (D) resolved 3 weeks later following the administration of corticosteroids.

Figure 2. Range of Vascular Imaging Findings in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019.

(A) CT venogram showing extensive thrombosis of cerebral venous sinuses (arrows: right transverse sinus clot extending into the torcula herophiles). (B) T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI sequences demonstrate symmetric, confluent white matter abnormalities in the parieto-occipital lobes consistent with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. (C) T2-weighted FLAIR MRI sequences with patchy infarcts within the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory. (D) Digital subtraction angiography showing diffuse vasculopathy of the M2 and M3 divisions of MCA and left pericallosal artery.

Electrographic Findings

EEG was completed in 11 cases (15%). In 1 case, the EEG was in normal, whereas in 10 cases, abnormalities included epileptiform discharges, triphasic waves, slowing, and frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity.

CSF Analysis

CSF was obtained in 9 cases (12%) and revealed a pleocytosis (9 total nucleated cells/μL) and elevated protein (72 mg/dL) in 1 case (an HIV-infected patient with cryptococcal meningoencephalitis) and an isolated elevated CSF protein (82 mg/dL) attributed to underlying diabetes mellitus in a second case (a patient with myoclonus).

Prognosis

There were 10 in-hospital mortalities within the cohort (14%). Neurologic diagnoses among deceased patients included toxic-metabolic encephalopathy (3 patients), ischemic stroke (2), intracerebral hemorrhage (1), seizure (1), syncope (1), anoxic brain injury (1), and myoclonus (1). Cause of death in these patients included an upper gastrointestinal bleed in a patient who was anticoagulated for a deep vein thrombosis, a ruptured superior mesenteric artery aneurysm resulting in hemorrhagic shock in a patient with bacterial endocarditis, and multiorgan failure involving the kidneys, lungs, and heart in the remaining 8 patients. Six patients had transitioned to comfort measures based on their goals of care before death.

Among survivors, the median mRS score was 4, indicating moderately severe disability, from a preadmission mRS score of 2, indicating slight disability. Twenty-seven patients were discharged home with or without home health services (36%), 20 to skilled nursing facilities (27%, including 11 who had previously been living at home), 9 to acute rehabilitation (12%, including 8 who had previously been living at home), and 3 to long-term acute care hospitals (4%, including 2 had previously been living at home and 1 who was previously unhoused). Five patients were discharged to hospice, either at home or inpatient (7%).

Discussion

Although neurologic complications of COVID-19 are described in the literature, existing publications focus on case reports and small series illustrating particular manifestations, with few large cohort studies.24,25,32 The largest previously published neurology-focused cohorts include 58 critically ill patients hospitalized in Strasbourg, France, and 153 patients with both neurologic and neuropsychiatric complications in a UK-wide surveillance study.24,25 No large US neurologic cohorts have been published in the literature, and despite robust data suggesting that both race and socioeconomic factors contribute to disparate rates of infection and prognoses, neither the French nor the British studies described the racial or socioeconomic makeup of their cohort. By contrast, we characterize neurologic findings in a racially and socioeconomically diverse cohort of patients with COVID-19.

The cohort described included a majority of patients who relied on government payors for insurance, including Medicaid, Medicare, MassHealth, and the Massachusetts Health Safety Net program. A majority of patients self-identified as Black or African American. A substantial minority of patients identified as unhoused or housing insecure before admission. These findings are consistent with a prior study of 2,729 patients with COVID-19 who were cared for in both the inpatient and outpatient settings at BMC, which found that nearly one-half were Black, approximately one-third were Hispanic, and 1 in 6 were experiencing homelessness.33

Neurologic findings spanned inflammatory complications (e.g., postinfectious bilateral Bell palsies, commonly known as Bell's palsies), vascular pathologies (e.g., ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis), sequelae of critical illness (e.g., anoxic brain injury and myoclonus), metabolic pathologies (e.g., uremic encephalopathy and osmotic demyelination syndrome), possible direct involvement of the nervous system by SARS-CoV-2 (e.g., a patient with pachymeningeal enhancement on brain MRI), and exacerbations of underlying neurologic conditions (e.g., a patient with underlying neuro-Behçet disease with MRI findings suggestive of a flare in the setting of active COVID-19). Taken together, these findings demonstrate a broad range of etiologies of acute neurologic complications in patients with COVID-19. The majority of patients did not require critical care, suggesting that neurologic complications may be common in patients with moderate COVID-19 and those with severe disease.

Among those with postinfectious complications, 1 patient developed imaging findings and seizures concerning for an autoimmune encephalitis, with improvement in imaging following the administration of corticosteroids, a rarely described complication of COVID-19.34 CSF was obtained in just 9 cases, with an incidentally elevated protein in 1 case and elevated protein and nucleated cell count in a second case, an immunocompromised patient with an opportunistic, non-COVID meningoencephalitis. These findings are consistent with prior reports documenting unrevealing CSF protein and cell count findings in the setting of COVID-19, even in patients diagnosed with an infectious or parainfectious encephalitis and in patients with positive CSF testing for SARS-CoV-2.13,14,24,35 However, published data are limited, and further studies are needed to elucidate the significance of these findings.

Among patients with ischemic stroke, cardioembolic strokes were most common. Although infrequently reported in prior literature regarding COVID-19,5,6 movement disorders were also common, with mechanisms ranging from metabolic derangements in a patient who developed osmotic demyelination syndrome with parkinsonian features to anoxic injury in a patient with myoclonus. Three patients presented with traumatic brain injuries following falls at home, highlighting the risk of neurologic injury in the setting of inadequate social support and isolation, even in the setting of mild SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Prognoses were variable, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 14%, higher than previously published in-hospital mortality rates in diverse non-neurologic inpatient cohorts.36 Patients who survived to discharge had moderately severe disability from a preadmission baseline of mild disability; however, the majority of patients were able to be discharged home with or without home health services.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. It is possible that some patients with neurologic complications were not evaluated by or admitted to the neurology or neurocritical care services and therefore were not included in the analysis. This may have included patients with mild neurologic symptoms who did not require subspecialty care and critically ill patients who were intubated, sedated, or paralyzed with a limited neurologic examination or otherwise poor prognosis. Because of the observational nature of this study, ancillary testing was not standardized across all patients, with variable investigations performed. Finally, the focus of this study was on acute neurologic findings in hospitalized patients, without analysis of posthospital complications or mortality.

Prior studies have unequivocally demonstrated that the infection rates, morbidity, and mortality associated with COVID-19 are affected by long-standing socioeconomic and racial disparities, which often affect health care access and utilization, underlying medical conditions, and employment and housing circumstances.33 Because of the sample size of our study and the small number of patients affected by each individual neurologic finding, we were unable to assess for statistically significant associations between these critical factors and neurologic prognosis. However, our findings reflect the neurologic experiences of an urban, safety-net US medical center caring for a socioeconomically and racially diverse patient population at high risk of adverse health outcomes, particularly in the setting of COVID-19, an experience that has not been represented in the literature to date. Future studies may explore whether factors such as housing security, access to primary care, or insurance status may be protective against neurologic complications of COVID-19.

Further studies are needed to fully understand the unique neurologic risk profile of this vulnerable patient population given the disparate impact of COVID-19. These include larger, multicenter studies to characterize both the impact of health care disparities on the frequency and severity of specific neurologic complications of COVID-19 and the impact of underlying neurologic conditions and other medical comorbidities on patient outcomes after COVID-19. Planned studies at our center include a prospective study to characterize long-term neurologic sequelae among both hospitalized and ambulatory survivors of COVID-19 to determine whether illness severity, demographic and socioeconomic differences, immunologic profiles, comorbidities, or other underlying factors either predispose to or protect against neurologic complications, with the goal of leveraging these findings for early identification and preventive measures for those patients at highest risk.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ A broad range of etiologies of acute neurologic complications can be seen in patients with COVID-19.

→ Acute neurologic complications of COVID-19 may include parainfectious inflammatory diseases, vascular pathologies, sequelae of critical illness, metabolic disorders, possible direct involvement of the nervous system by SARS-CoV-2, and exacerbations of underlying neurologic conditions.

→ Further studies are needed to fully understand the breadth of neurologic findings associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in diverse patient populations given the disparate impact of COVID-19.

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Lan Zhou, Email: lan.zhou@bmc.org.

Nahid Bhadelia, Email: nbhadeli@bu.edu.

Davidson H. Hamer, Email: dhamer@bu.edu.

David M. Greer, Email: dgreer@bu.edu.

Anna M. Cervantes-Arslanian, Email: anna.cervantes@bmc.org.

Study Funding

This work is supported by a Simon Grinspoon Research Grant (P. Anand).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Greenland JR, Michelow MD, Wang L, London MJ. COVID-19 infection: implications for perioperative and critical care physicians. Anesthesiology 2020;132:1346–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asadi-Pooya AA. Seizures associated with coronavirus infections. Seizure 2020;79:49–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu L, Xiong W, Liu D, et al. New onset acute symptomatic seizure and risk factors in coronavirus disease 2019: a retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia 2020;61:e49–e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand P, Al-Faraj A, Sader E, et al. Seizure as the presenting symptom of COVID-19. Epilepsy Behav 2020;112:107335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anand P, Zakaria A, Benameur K, et al. Myoclonus in patients with COVID-19: a multicenter case series. Crit Care Med 2020;48:1664–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rábano-Suárez P, Bermejo-Guerrero L, Méndez-Guerrero A, et al. Generalized myoclonus in COVID-19. Neurology 2020;95:e767–e772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberti P, Beretta S, Piatti M, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome related to COVID-19 infection. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2020;7:e741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, Liu J, Chen S. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol 2020;19:383–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyrouti R, Adams ME, Benjamin L, et al. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020;91:889–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of COVID-19 in the young. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carneiro T, Dashkoff J, Leung LY, et al. Intravenous tPA for acute ischemic stroke in patients with COVID-19. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020;29:105201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes C, Nichols T, Pike M, Subbe C, Elghenzai S. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis as a presentation of COVID-19. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med 2020;7:001691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye M, Ren Y, LT. Encephalitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:945–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis 2020;94:55–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand P, Lau KHV, Chung DY, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: two cases and a review of the literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020;29:105212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Princiotta Cariddi L, Tabaee Damavandi P, Carimati F, et al. Reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in a COVID-19 patient. J Neurol 2020;267:3157–3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaya Y, Kara S, Akinci C, Kocaman AS. Transient cortical blindness in COVID-19 pneumonia; a PRES-like syndrome: case report. J Neurol Sci 2020;413:116858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haddad S, Tayyar R, Risch L, et al. Encephalopathy and seizure activity in a COVID-19 well controlled HIV patient. IDCases 2020;21:e00814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, Stone M, Patel S, Griffith B. COVID-19–associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology 2020;296:e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franceschi AM, Ahmed O, Giliberto L, Castillo M. Hemorrhagic posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome as a manifestation of COVID-19 infection. Am J Neuroradiol 2020;41:1173–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koralnik IJ, Tyler KL. COVID-19: a global threat to the nervous system. Ann Neurol 2020;88:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:683–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol 2020;19:767–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-COV-2 infection. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2268–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:875–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaya S, Yeboah H, Charles CH, Otu A, Labonte R. Ethnic and racial disparities in COVID-19-related deaths: counting the trees, hiding the forest. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baqui P, Bica I, Marra V, Ercole A, van der Schaar M. Ethnic and regional variations in hospital mortality from COVID-19 in Brazil: a cross-sectional observational study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e1018–e1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boston Medical Center. Boston Medical Center Homepage. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Cases in the United States. Atlanta: CDC COVID Data Tracker; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.CDC. Trends in Number of COVID-19 Cases in the US Reported to CDC, by State/Territory. Atlanta: CDC COVID Data Tracker; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.H PAdams J, EMarsh E III. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrarese C, Silani V, Priori A, et al. An Italian multicenter retrospective-prospective observational study on neurological manifestations of COVID-19 (NEUROCOVID). Neurol Sci 2020;41:1355–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu HE, Ashe EM, Silverstein M, et al. Race/ethnicity, underlying medical conditions, homelessness, and hospitalization status of adult patients with COVID-19 at an urban safety-net medical center—Boston, Massachusetts, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:864–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilotto A, Odolini S, Masciocchi S, et al. Steroid-responsive encephalitis in coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Neurol 2020;88:423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pugin D, Vargas MI, Thieffry C, et al. COVID-19-related encephalopathy responsive to high doses glucocorticoids. Neurology 2020;95:543–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gold JAW, Wong KK, Szablewski CM, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19—Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:545–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.