Abstract

The incidence of Tuberculosis (TB) in Guizhou province has ranked to be the top four among the 31 China provinces. The spatial distribution and influencing factors of adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou are unclear. In our study, the cases information of TB in Guizhou province from 2013 to 2018 was collected, we analyzed the spatial distribution and clusters of five adverse outcomes of TB with ArcMap10.2 software, used logistics regression analysis to assessed risk factors and used Chi-square analysis to analyze variation trend of the five adverse outcomes. A total of 237, 806 cases information of TB were collected. The proportion of adverse outcomes in TB patients was 6.18%, among which adverse reactions accounted for 1.05%, lost to follow-up accounted for 1.44%, treatment failed accounted for 1.15%, died accounted for 2.31%, switch to MDR accounted for 0.24%. The component ratio of adverse outcomes showed an upward trend (P < 0.05).Regional clustering existed in each of adverse outcomes (P < 0.05). There were high-risk minorities, gender, age, occupation, type of diagnosis, Therapeutic category existed in adverse outcomes of TB. Miao and Dong had a higher risk in adverse reaction of TB compared with Han. Women had a higher risk in adverse reactions than men, and a lower risk of lost to follow-up, failed, and died. Retreated patients had a higher risk of adverse outcomes. Timely monitoring and active intervention should be carried out for some high-risk areas and groups, including middle-aged and elderly patients, rural patients, floating patients, severe patients and retreated patients during the process of patient diagnosis and treatment.

Subject terms: Diseases, Health care, Health occupations, Risk factors

Introduction

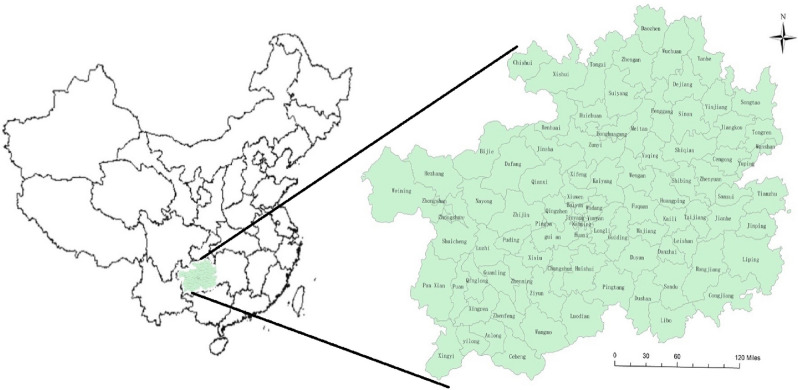

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic respiratory infectious disease caused by mycobacterium tuberculosis, which is one of the top ten causes of death worldwide, it is a serious infectious disease in some developing countries. China is one of 22 high TB burden countries in the world1. Male, farmers and middle-aged people are the main groups of TB patients. The incidence of TB in western China is higher than in central and eastern2. In 2018, China ranked the fourth in the world with incidence of 59/100,0003. Guizhou province is located in the west of China with 88 counties and 49 ethnic minorities (Fig. 1). From 2013 to 2018, more than 40,000 TB cases were reported in Guizhou province every year4, the reported incidence of TB in 2019 was 102/100,000. In addition, the treatment of TB is not entirely free in China, many patients' families were not rich, who need to pay about 22% of the total family income during the treatment process5,6. It will bring greater mental harm and economic burden to the patients and their families if these patients have a bad outcome of TB7,8.

Figure 1.

Location of Guizhou Province, China (ArcGis 10.2 software).

It has been widely seen to analyze the epidemic characteristics of TB with spatial and temporal method9–12. Spatial–temporal analysis extends the analysis of epidemics in spatial epidemiology13,14, which can predict the spatial–temporal trends and correlations of diseases, explore spatial distribution models in spatial epidemiology15, objectively present the distribution characteristics of diseases with quantitative methods, and describe the clustering characteristics between time and space with scanning statistics16,17. But this method has rarely been used in studies of adverse outcomes of TB18–21, previous studies did not analyze every adverse outcomes of TB at the same time. However, it was rare to analyze adverse outcomes of TB with spatial distribution analysis22–27. Meanwhile, the spatial distribution and risk factors of adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou are unclear. Our research’s purpose was to analyze the time and space characteristics of five adverse outcomes of TB, and assessed the risk factors and variation trend of the adverse outcomes of TB, so as to provide the evidence for timely monitoring and active intervention of the high-risk areas and groups in Guizhou province.

Materials and methods

Date source

Our data of TB cases came from China information system of disease prevention and control, the data was downloaded according to the conditions of onset date, current address, audited status. Through this system, the medical record information of all registered and managed TB patients in 88 counties of Guizhou province from 2013 to 2018 was obtained, among which the cases with unknown address, changed diagnosis, no treatment outcome or suspected diagnosis were excluded. The population data came from the Statistics Bureau of Guizhou Province in the same period.

Indicators and definitions

The outcomes of TB treatment include cured, treatment completed, adverse reactions, lost to follow-up, treatment failed, died, and switch to multi-drug resistance (switch to MDR), these indicators are defined in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) standards28, adverse reactions are included in the treatment failure in this standard, but which are used as a separate evaluation index in our study. In addition, we also used switch to MDR as one of the evaluation indicators of adverse outcomes. So there are five adverse outcomes of TB in our study, including adverse reactions, lost to follow-up, treatment failed, died and switch to MDR. The outcomes of TB treatment are defined as follows:

Cured Treatment completed as recommended by the national policy without evidence of failure and three or more consecutive cultures taken at least 30 days apart are negative after the intensive phase28.

Treatment completed Treatment completed as recommended by the national policy without evidence of failure but no record that three or more consecutive cultures taken at least 30 days apart are negative after the intensive phase28.

Treatment failed Treatment terminated or need for permanent regimen change of at least two anti-TB drugs because of: Lack of conversion by the end of the intensive phase; or bacteriological reversion in the continuation phase after conversion to negative; or evidence of additional acquired resistance to fluoroquinolones or second-line injectable drugs28.

Died A patient who dies for any reason during the course of treatment28.

Lost to follow-up A patient whose treatment was interrupted for two consecutive months or more28.

Adverse reactions A harmful and/or undesirable reaction caused by a prescribed drug in a treated patient when used in the correct manner and at the correct dosage28.

Switch to MDR An ordinary TB patient receiving treatment develops resistance to one or more anti-TB drugs after a period of treatment.

Component ratio (CR) of adverse outcomes of TB refers to the proportion of the number of TB patients with adverse outcome accounting for the total number of TB patients in this year, including the CR of adverse reaction, the CR of lost to follow-up, the CR of treatment failed, the CR of died and CR of switch to MDR, which are used to describe the variation trend of adverse outcomes of TB.

Rate of adverse outcomes refers to the proportion of the number of TB patients with adverse outcome in the total number of TB patients in a region, we take 1/1000 as the proportion unit, including rate of adverse reaction, rate of lost to follow-up, rate of treatment failed, rate of died and rate of switch to MDR, which are used to describe the spatial distribution of adverse outcome of TB.

In the analysis of risk factors, the factors included gender, age, nationality, occupation, local registered residence, source of patients, clinical classification, diagnostic results, severe cases, and therapeutic category.

Spatial analysis

According to the cases of current address, we got the case's national standard area code's information, the spatial location of TB patients would be associated with vectorized electronic maps of Guizhou, the prevalence of adverse outcomes of TB in counties (districts) would be established in the form of geographic information, and ArcMap10.2 software was used to calculate the local indicators of spatial association (LISA), among which there are four types of cluster diagrams, including High–High (HH), Low–Low (LL), High–Low (HL) and Low–High (LH). The HH indicates that the rate of adverse outcomes in the region is high and the rate of adverse outcomes in neighboring region is still high. The LL indicates that the rate of adverse outcomes in the region is low and the rate of adverse outcomes in neighboring region is still low. The HL indicates that the rate of adverse outcomes in the region is high and the rate of adverse outcomes in neighboring region is low. The LH indicates that the rate of adverse outcomes in the region is low and the rate of adverse outcomes in neighboring region is high.

Analysis of risk factors

In the study of the risk factors, the factors included gender, age, nationality, occupation, local registered residence, source of patients, clinical classification, diagnostic results, severe cases, and therapeutic category. We first conducted univariate logistics regression analysis for each adverse outcome. When univariate logistics analysis was statistically significant (P < 0.05), the factor would be subjected to multivariable logistics regression analysis, and the statistical software was SPSS22.0.

Results

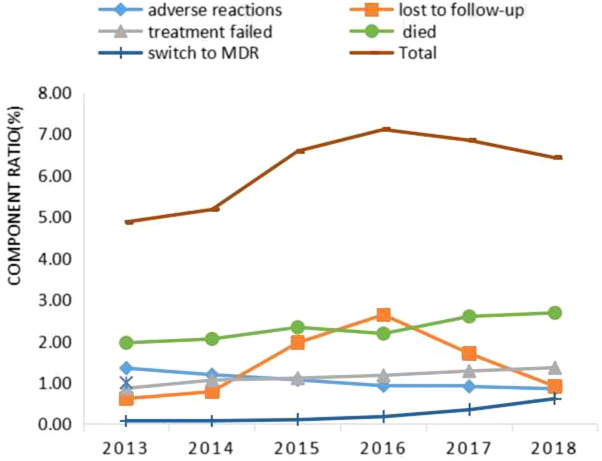

We obtained a total of medical record of 237,806 cases according to the requirements of data in our study, including 40,381 cases in 2013, 37,838 in 2014, 39,266 in 2015, 39,611 in 2016, 39,622 in 2017, and 41,088 in 2018.The proportion of adverse outcomes in TB patients was 6.18%, among which adverse reactions accounted for 1.05%, lost to follow-up accounted for 1.44%, treatment failed accounted for 1.15%, died accounted for 2.31%, and switch to MDR accounted for 0.24%. The CR of total adverse outcomes showed an upward trend (P < 0.05), among which except the CR of adverse reactions showed a downward trend (P < 0.05), and the CR of lost to follow-up, treatment failed, died and switch to MDR showed an upward trend (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Variation trends (p < 0.05) of the component ratio (CR) of adverse outcomes in TB Patients (%), Guizhou, China, 2013–2018.

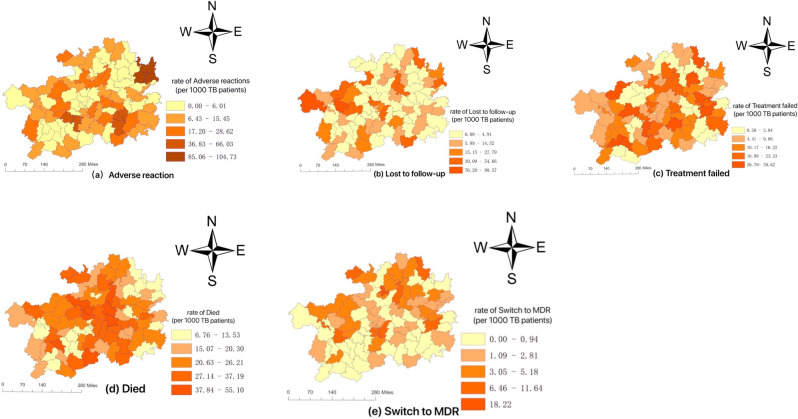

Spatial distribution and clusters

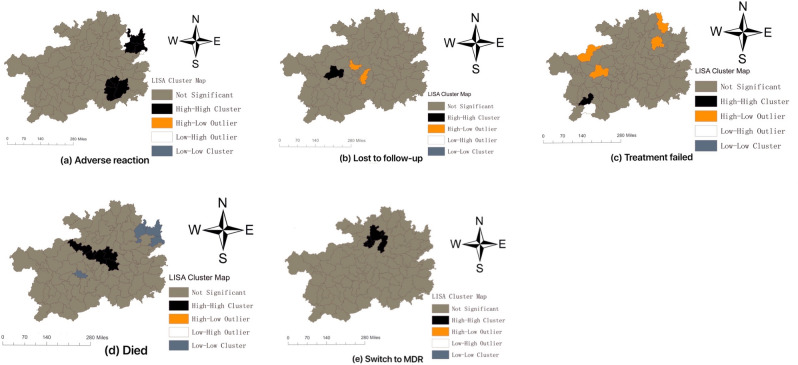

The spatial distribution of adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou were irregular, and the five adverse outcomes of TB showed their own distribution characteristics (Fig. 3). The five adverse outcomes showed their own characteristics of spatial clusters (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

The spatial distribution of adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou during 2013–2018. (a) Geographic distribution of rate of adverse reaction; (b) Geographic distribution of rate of lost to follow-up; (c) Geographic distribution of rate of treatment failed; (d) Geographic distribution of rate of died; (e) Geographic distribution of rate of switch to MDR.

Figure 4.

Maps of the local indicators of spatial association (LISA) of adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou during 2013–2018. (a) Spatial clusters of rate of adverse reaction; (b) Spatial clusters of rate of lost to follow-up; (c) Spatial clusters of rate of treatment failed; (d) Spatial clusters of rate of died; (e) Spatial clusters of rate of switch to MDR.

There were two clusters in adverse reactions of TB in Guizhou, which contained Tongren City (including Wanshan, Dejiang, Yuping, Bijiang County) and Qiandongnan city (including Rongjiang, Leishan, Danzhai County) (Fig. 4a).

There was a cluster in lost to follow-up of TB in Guizhou (Fig. 4b). Zhijin County (Bijie City) was the region with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in HH (Fig. 4b), and there were two regions (including Longli and Xiuwen County) with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in HL (Fig. 4b).

Xingren County was a region with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in HH about treatment failed of TB in Guizhou (Fig. 4c), there were four regions with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in HL, including Qixingguan, Zhijin, Songtao and Yinjiang County (Fig. 4c). Anlong County was the region with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in LH (Fig. 4c).

There was a cluster in died of TB in Guizhou (Fig. 4d). There were five regions with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in HH, including Jinsha, Xifeng, Kaiyang, Fuquan and Wengan County, there were four regions with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in LL, including Dejiang, Wanshan, Bijiang and Pingba County (Fig. 4d).

There was a cluster in switch to MDR of TB in Guizhou (Fig. 4e). There were four regions with statistical significance (P < 0.05) in HH, including Suiyang, Huichuan, Honghuagang and Meitan County, these four areas were concentrated in Zunyi City (Fig. 4e).

Risk factors

In our study on risk factors of adverse reactions in TB patients, women had a higher risk compared with men. The higher the age, the higher the risk. Miao, Dong and Others had a higher risk compared with Han, Buyi and Tujia had a lower risk. Compared with peasant workers, the homemakers and unemployed persons, Retired persons and cadres and staffs had a higher risk, while students had a lower risk. Compared with local patients, the non-local patients had a lower risk. Recommendation for symptoms had a higher risk compared to clinical consultation. Compared with positive etiology, the negative etiology and pure tuberculous pleurisy had a higher risk. Non-severe had a higher risk compared to severe. Re-treatment had a higher risk compared with initial treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of risk factors analysis of adverse reactions in TB patients.

| Variables | n | Rate of adverse reactions (per 1000 TB) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 1579 | 66.40 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Females | 916 | 38.52 | 1.12 (1.04–1.22) | 0.005 | 1.15 (1.06–1.25) | 0.001 |

| Age | ||||||

| 0~ | 126 | 5.30 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 20~ | 529 | 22.25 | 1.63 (1.34–1.98) | < 0.001 | 1.49 (1.21–1.84) | < 0.001 |

| 40~ | 756 | 31.79 | 2.37 (1.96–2.86) | < 0.001 | 2.20 (1.79–2.71) | < 0.001 |

| 60~ | 1084 | 45.58 | 3.99 (3.32–4.84) | < 0.001 | 3.69 (3.01–4.52) | < 0.001 |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Han | 1570 | 66.02 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Miao | 372 | 15.64 | 1.30 (1.17–1.46) | < 0.001 | 1.38 (1.23–1.54) | < 0.001 |

| Buyi | 154 | 6.48 | 0.82 (0.70–0.97) | 0.022 | 0.83 (0.70–0.98) | 0.031 |

| Yi | 51 | 2.14 | 0.75 (0.57–1.00) | 0.046 | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) | 0.412 |

| Dong | 152 | 6.39 | 1.75 (1.48–2.07) | < 0.001 | 1.88 (1.59–2.23) | < 0.001 |

| Tujia | 71 | 2.99 | 0.61 (0.48–0.77) | < 0.001 | 0.59 (0.47–0.75) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 125 | 5.26 | 1.49 (1.24–1.79) | < 0.001 | 1.59 (1.32–1.91) | < 0.001 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Peasant workers | 2082 | 87.55 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Homemakers and unemployed persons | 153 | 6.43 | 1.26 (1.07–1.49) | 0.006 | 1.60 (1.35–1.90) | < 0.001 |

| Students | 91 | 3.83 | 0.43 (0.35–0.54) | < 0.001 | 0.73 (0.58–0.93) | 0.009 |

| Retired persons and cadres and staff | 94 | 3.95 | 1.94 (1.57–2.38) | < 0.001 | 1.68 (1.36–2.07) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 75 | 3.15 | 0.72 (0.57–0.90) | 0.005 | 0.91 (0.72–1.15) | 0.420 |

| Local registered residence | ||||||

| Yes | 2305 | 96.93 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 190 | 7.99 | 0.74 (0.64–0.86) | < 0.001 | 0.78 (0.66–0.90) | 0.001 |

| Source of patients | ||||||

| Clinical consultation | 1134 | 47.69 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Referral | 787 | 33.09 | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.862 | 0.97 (0.89–1.07) | 0.543 |

| Following up | 413 | 17.37 | 1.00 (0.90–1.12) | 0.956 | 1.02 (0.91–1.15) | 0.740 |

| Recommended for symptoms | 88 | 3.70 | 1.97(1.58–2.45) | < 0.001 | 2.17 (1.74–2.70) | 0.001 |

| Physical examinations | 41 | 1.72 | 0.73 (0.53–0.99) | 0.046 | 1.13 (0.82–1.55) | 0.460 |

| Others | 32 | 1.35 | 1.08 (0.76–1.54) | 0.677 | 1.16 (0.82–1.66) | 0.405 |

| Clinical classification | ||||||

| Type I | 0 | 0.00 | Referent | |||

| Type II | 51 | 2.14 | 0.00 | 0.996 | ||

| Type III | 2375 | 99.87 | 0.83 (0.39–1.75) | 0.619 | ||

| Type IV | 61 | 2.57 | 0.68 (0.34–1.36) | 0.275 | ||

| Type V | 8 | 0.34 | 0.66 (0.32–1.39) | 0.274 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Etiological positivity | 723 | 30.40 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Etiological negative | 1709 | 71.87 | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) | 0.003 | 1.27 (1.17–1.41) | < 0.001 |

| Pure tuberculous pleurisy | 55 | 2.31 | 1.41 (1.07–1.85) | 0.015 | 1.81 (1.37–2.39) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 8 | 0.34 | 1.10 (0.54–2.21) | 0.800 | 1.52 (0.75–3.07) | 0.246 |

| Severe cases | ||||||

| Yes | 296 | 12.45 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 2199 | 92.47 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 0.003 | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | 0.001 |

| Therapeutic category | ||||||

| Initial treatment | 2250 | 94.61 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Re-treated | 245 | 10.30 | 1.62 (1.42–1.85) | < 0.001 | 1.65 (1.44–1.90) | < 0.001 |

In the study on risk factors of lost to follow up, women had a lower risk compared with men. The higher risk was 20 to 39 years compared with 0 to 19 years. Compared with Han, Yi had a higher risk, Buyi, Dong, Tujia and Others had a lower risk. Compared with peasant workers, the Retired persons and cadres and staffs, Others had a lower risk. Compared with local patients, the non-local had a higher risk. Referral and following up had a lower risk compared with clinical consultation. Compared with Type I, the Type III, Type IV and Type V had a higher risk. Pure tuberculous pleurisy and others had a higher risk compared with positive etiology. Non-severe had a lower risk compared to severe. Re-treatment had a higher risk compared with initial treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of risk factors analysis of lost to follow up in TB patients.

| Variables | n | Rate of Lost to follow up (per 1000 TB) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 2443 | 102.73 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Females | 972 | 40.87 | 0.77 (0.71–0.83) | < 0.001 | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||||

| 0~ | 382 | 16.06 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 20~ | 1155 | 48.57 | 1.17 (1.04–1.32) | 0.008 | 1.18 (1.04–1.35) | 0.009 |

| 40~ | 1015 | 42.68 | 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 0.485 | 1.06 (0.93–1.20) | 0.43 |

| 60~ | 863 | 36.29 | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | 0.578 | 1.13 (0.99–1.30) | 0.076 |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Han | 2420 | 101.76 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Miao | 450 | 18.92 | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) | 0.689 | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 0.461 |

| Buyi | 163 | 6.85 | 0.56 (0.48–0.66) | < 0.001 | 0.57 (0.48–0.67) | < 0.001 |

| Yi | 200 | 8.41 | 1.95 (1.68–2.23) | < 0.001 | 1.82 (1.57–2.11) | < 0.001 |

| Dong | 53 | 2.23 | 0.39 (0.30–0.51) | < 0.001 | 0.39 (0.29–0.51) | < 0.001 |

| Tujia | 37 | 1.56 | 0.20 (0.15–0.28) | < 0.001 | 0.22 (0.16–0.30) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 92 | 3.87 | 0.71 (0.57–0.87) | 0.001 | 0.71 (0.58–0.87) | 0.001 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Peasant workers | 2787 | 117.20 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Homemakers and unemployed persons | 192 | 8.07 | 1.18 (1.02–1.37) | 0.026 | 1.12 (0.96–1.30) | 0.148 |

| Students | 283 | 11.90 | 1.01 (0.90–1.15) | 0.843 | 1.07 (0.93–1.23) | 0.323 |

| Retired persons and cadres and staff | 36 | 1.51 | 0.54 (0.39–0.76) | < 0.001 | 0.56 (0.41–0.79) | 0.001 |

| Others | 117 | 4.92 | 0.83 (0.69–1.01) | 0.056 | 0.81 (0.67–0.98) | 0.027 |

| Local registered residence | ||||||

| Yes | 3067 | 128.97 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 348 | 14.63 | 1.02 (0.91–1.14) | 0.728 | 1.18 (1.05–1.32) | 0.005 |

| Source of patients | ||||||

| Clinical consultation | 1777 | 74.72 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Referral | 1065 | 44.78 | 0.87 (0.81–0.94) | < 0.001 | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) | < 0.001 |

| Following up | 382 | 16.06 | 0.59 (0.53–0.66) | < 0.001 | 0.59 (0.52–0.66) | < 0.001 |

| Recommended for symptoms | 71 | 2.99 | 1.00 (0.79–1.27) | 0.980 | 0.90 (0.71–1.15) | 0.411 |

| Physical examinations | 73 | 3.07 | 0.83 (0.65–1.05) | 0.112 | 0.87 (0.69–1.11) | 0.268 |

| Others | 47 | 1.98 | 1.01 (0.75–1.35) | 0.949 | 1.06 (0.79–1.42) | 0.705 |

| Clinical classification | ||||||

| Type I | 0 | 0.00 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Type II | 62 | 2.61 | 0.00 | 0.996 | 0.00 | 0.996 |

| Type III | 3109 | 130.74 | 1.62 (0.65–4.05) | 0.301 | 2.71 (1.06–6.93) | 0.038 |

| Type IV | 239 | 10.05 | 1.43 (0.59–3.46) | 0.424 | 2.74 (1.11–6.79) | 0.029 |

| Type V | 5 | 0.21 | 4.30 (1.76–10.47) | 0.001 | 3.93 (1.61–9.60) | 0.003 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Etiological positivity | 1109 | 46.63 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Etiological negative | 2083 | 87.59 | 0.90 (0.84–0.97) | 0.007 | 1.06 (0.98–1.15) | 0.142 |

| Pure tuberculous pleurisy | 205 | 8.62 | 3.53 (3.03–4.11) | < 0.001 | 3.28 (2.51–4.30) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 18 | 0.76 | 1.62 (1.01–2.59) | 0.045 | 2.34 (1.45–3.77) | < 0.001 |

| Severe cases | ||||||

| Yes | 652 | 27.42 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 2763 | 116.19 | 0.68 (0.62–0.74) | < 0.001 | 0.67 (0.62–0.74) | < 0.001 |

| Therapeutic category | ||||||

| Initial treatment | 2965 | 124.68 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Re-treated | 450 | 18.92 | 2.29 (2.07–2.53) | < 0.001 | 2.17 (1.96–2.42) | < 0.001 |

In the study on risk factors of treatment failed, women had a lower risk compared with men. Over 20 years of age had a higher risk compared with 0 to 19 years. The differences between ethnic groups were not statistically significant. Compared with peasant workers, others had a lower risk. There was no statistically significant difference between regions. Compared with clinical consultation, Recommendation for symptoms had a higher risk, while referral and following-up had a lower risk. Compared with positive etiology, negative etiology, pure tuberculous pleurisy and others had a lower risk. Non-severe had lower risk compared to severe. Retreatment had a higher risk compared with initial treatment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of risk factors analysis of treatment failed in TB patients.

| Variables | n | Rate of treatment failed (per 1000 TB) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 2055 | 86.41 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Females | 668 | 28.09 | 0.63 (0.57–0.68) | < 0.001 | 0.72 (0.66–0.78) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||||

| 0~ | 148 | 6.22 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 20~ | 643 | 27.04 | 1.68 (1.41–2.01) | < 0.001 | 1.34 (1.12–1.62) | 0.003 |

| 40~ | 1140 | 47.94 | 3.05 (2.57–3.63) | < 0.001 | 2.17 (1.80–2.61) | < 0.001 |

| 60~ | 792 | 33.30 | 2.47 (2.07–2.95) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.56–2.28) | < 0.001 |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Han | 1789 | 75.23 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Miao | 326 | 13.71 | 1.00 (0.89–1.13) | 0.998 | 0.94 (0.83–1.06) | 0.279 |

| Buyi | 239 | 10.05 | 1.13 (0.98–1.29) | 0.089 | 1.08 (0.94–1.24) | 0.289 |

| Yi | 77 | 3.24 | 1.95 (1.68–2.23) | 0.993 | 0.99 (0.79–1.25) | 0.946 |

| Dong | 98 | 4.12 | 1.00 (0.79–1.26) | 0.862 | 0.83 (0.68–1.02) | 0.083 |

| Tujia | 122 | 5.13 | 0.98 (0.80–1.21) | 0.384 | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) | 0.758 |

| Others | 72 | 3.03 | 0.92 (0.77–1.11) | 0.016 | 0.80 (0.63–1.01) | 0.058 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Peasant workers | 2340 | 98.40 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Homemakers and unemployed persons | 137 | 5.76 | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | 0.977 | 1.11 (0.93–1.33) | 0.237 |

| Students | 131 | 5.51 | 0.56 (0.47–0.66) | < 0.001 | 0.92 (0.76–1.11) | 0.380 |

| Retired persons and cadres and staff | 43 | 1.81 | 0.78 (0.57–1.05) | 0.104 | 0.77 (0.57–1.05) | 0.059 |

| Others | 72 | 3.03 | 0.61 (0.48–0.77) | < 0.001 | 0.72 (0.57–0.91) | 0.007 |

| Local registered residence | ||||||

| Yes | 2489 | 104.67 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 234 | 9.84 | 0.84 (0.74–0.97) | 0.013 | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) | 0.652 |

| Source of patients | ||||||

| Clinical consultation | 1323 | 55.63 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Referral | 836 | 35.15 | 0.92 (0.84–1.00) | 0.051 | 0.87 (0.80–0.95) | 0.002 |

| Following up | 384 | 16.15 | 0.80 (0.71–0.89) | < 0.001 | 0.86 (0.76–0.97) | 0.011 |

| Recommended for symptoms | 96 | 4.04 | 1.84 (1.49–2.27) | < 0.001 | 1.49 (1.20–1.84) | < 0.001 |

| Physical examinations | 33 | 1.39 | 0.50 (0.35–0.71) | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.69–1.39) | 0.897 |

| Others | 51 | 2.14 | 1.48 (1.12–1.96) | 0.006 | 1.29 (0.97–1.71) | 0.086 |

| Clinical classification | ||||||

| Type I | 0 | 0.00 | Referent | |||

| Type II | 25 | 1.05 | 10,145,695.39 (0.00) | 0.996 | ||

| Type III | 2673 | 112.40 | 19,244,084.80 (0.00) | 0.996 | ||

| Type IV | 25 | 1.05 | 6,785,381.10 (0.00) | 0.996 | ||

| Type V | 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.000 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Etiological positivity | 1758 | 73.93 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Etiological negative | 950 | 39.95 | 0.26 (0.24–0.28) | < 0.001 | 0.31 (0.29–0.34) | < 0.001 |

| Pure tuberculous pleurisy | 11 | 0.46 | 0.11 (0.06–0.20) | < 0.001 | 0.17 (0.09–0.30) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 4 | 0.17 | 0.22 (0.08–0.59) | 0.003 | 0.34 (0.13–0.91) | 0.032 |

| Severe cases | ||||||

| Yes | 782 | 32.88 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 1941 | 81.62 | 0.40 (0.36–0.43) | < 0.001 | 0.48 (0.44–0.52) | < 0.001 |

| Therapeutic category | ||||||

| Initial treatment | 2224 | 93.52 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Re-treated | 499 | 20.98 | 3.40 (3.08–3.75) | < 0.001 | 1.87 (1.69–2.07) | < 0.001 |

In the study on risk factors of died, women had a lower risk compared with men. The risk increases with age. Compared with Han, Yi had a higher risk, Dong and Tujia had a lower risk. Students had a higher risk compared with peasant workers, while homemakers and unemployed persons, Retired persons and cadres and staffs and others had a lower risk. Compared with local patients, the non-local had a lower risk. Compared with clinical consultation, referral had a higher risk, while physical examination had a lower risk. Compared with positive etiology, negative etiology had a lower risk. Non-severe had a lower risk compared to severe. Retreatment had a higher risk compared with initial treatment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of risk factors analysis of died in TB patients.

| Variables | n | Rate of died (per 1000 TB) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 3989 | 167.74 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Females | 1503 | 63.20 | 0.72 (0.68–0.77) | < 0.001 | 0.72 (0.68–0.76) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||||

| 0~ | 77 | 3.24 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 20~ | 514 | 21.61 | 2.59 (2.04–3.29) | < 0.001 | 2.46 (1.92–3.15) | < 0.001 |

| 40~ | 1496 | 62.91 | 7.76 (6.17–9.76) | < 0.001 | 6.89 (5.48–8.75) | < 0.001 |

| 60~ | 3405 | 143.18 | 21.36 (17.04–26.79) | < 0.001 | 19.67 (15.52–24.93) | < 0.001 |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Han | 3739 | 157.23 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Miao | 650 | 27.33 | 0.95 (0.88–1.04) | 0.264 | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 0.343 |

| Buyi | 443 | 18.63 | 1.00 (0.90–1.10) | 0.940 | 0.98 (0.88–1.08) | 0.630 |

| Yi | 146 | 6.14 | 0.90 (0.77–1.07) | 0.238 | 1.23 (1.03–1.46) | 0.017 |

| Dong | 170 | 7.15 | 0.81 (0.70–0.95) | 0.008 | 0.74 (0.63–0.87) | < 0.001 |

| Tujia | 162 | 6.81 | 0.58 (0.50–0.68) | < 0.001 | 0.52 (0.45–0.62) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 182 | 7.65 | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | 0.192 | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | 0.968 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Peasant workers | 4911 | 206.51 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Homemakers and unemployed persons | 157 | 6.60 | 0.54 (0.46–0.64) | < 0.001 | 0.83 (0.71–0.98) | 0.028 |

| Students | 180 | 7.57 | 0.36 (0.31–0.42) | < 0.001 | 1.19 (1.01–1.39) | 0.036 |

| Retired persons and cadres and staff | 138 | 5.80 | 1.20 (1.01–1.42) | 0.039 | 0.82 (0.69–0.98) | 0.026 |

| Others | 106 | 4.46 | 0.42 (0.35–0.51) | < 0.001 | 0.68 (0.56–0.83) | < 0.001 |

| Local registered residence | ||||||

| Yes | 5127 | 215.60 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 365 | 15.35 | 0.63 (0.57–0.71) | < 0.001 | 0.79 (0.71–0.89) | < 0.001 |

| Source of patients | ||||||

| Clinical consultation | 2299 | 96.68 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Referral | 2195 | 92.30 | 1.40 (1.32–1.48) | < 0.001 | 1.22 (1.15–1.30) | < 0.001 |

| Following up | 843 | 35.45 | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 0.803 | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 0.731 |

| Recommended for symptoms | 90 | 3.78 | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 0.870 | 0.95 (0.77–1.18) | 0.666 |

| Physical examinations | 9 | 0.38 | 0.08 (0.04–0.15) | < 0.001 | 0.22 (0.11–0.42) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 56 | 2.35 | 0.93 (0.71–1.21) | 0.586 | 0.97 (0.74–1.28) | 0.851 |

| Clinical classification | ||||||

| Type I | 0 | 0.00 | Referent | |||

| Type II | 242 | 10.18 | 107,473,172.80 (0.00) | 0.996 | ||

| Type III | 5110 | 214.88 | 38,482,807.67 (0.00) | 0.996 | ||

| Type IV | 134 | 5.63 | 38,332,749.21 (0.00) | 0.996 | ||

| Type V | 6 | 0.25 | 19,480,213.23 (0.00) | 0.966 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Etiological positivity | 2513 | 105.67 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Etiological negative | 2878 | 121.02 | 0.54 (0.51–0.57) | < 0.001 | 0.62 (0.59–0.65) | < 0.001 |

| Pure tuberculous pleurisy | 88 | 3.70 | 0.64 (0.51–0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.91 (0.73–1.13) | 0.391 |

| Others | 13 | 0.55 | 0.50 (0.29–0.87) | 0.014 | 0.97 (0.55–1.69) | 0.902 |

| Severe cases | ||||||

| Yes | 1089 | 45.79 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 4403 | 185.15 | 0.65 (0.60–0.69) | < 0.001 | 0.72 (0.67–0.77) | < 0.001 |

| Therapeutic category | ||||||

| Initial treatment | 4900 | 206.05 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Re-treated | 592 | 24.89 | 1.82 (1.67–1.99) | < 0.001 | 1.23 (1.12–1.34) | < 0.001 |

In the study on the risk factors of switch to MDR, there was no difference between the genders. The risk factor is 40 to 59 years compared with 0 to 19 years. Miao and Buyi had a lower risk compared with Han. Homemakers and unemployed, retired persons and cadres and staffs had a higher risk compared with peasant workers. Compared with local patients, the non-local had a higher risk. Compared with clinical consultation, referral and others had a higher risk, following-up had a lower risk. Compared with positive etiology, negative etiology had a lower risk. Non-severe had lower risk compared to severe. Retreatment had a higher risk compared with initial treatment (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of risk factors analysis of switch to MDR in TB patients.

| Variables | n | Rate of switch to MDR (per 1000 TB) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 419 | 17.62 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Females | 150 | 6.31 | 0.69 (0.57–0.83) | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0.75–1.09) | 0.294 |

| Age | ||||||

| 0~ | 29 | 1.22 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 20~ | 179 | 7.53 | 2.39 (1.61–3.53) | < 0.001 | 1.39 (0.92–2.11) | 0.116 |

| 40~ | 234 | 9.84 | 3.17 (2.16–4.67) | < 0.001 | 1.49 (0.98–2.25) | 0.06 |

| 60~ | 127 | 5.34 | 2.01 (1.34–3.01) | 0.001 | 1.02 (0.66–1.57) | 0.938 |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Han | 424 | 17.83 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Miao | 53 | 2.23 | 0.69 (0.52–0.91) | 0.01 | 0.650.49–0.87) | 0.004 |

| Buyi | 16 | 0.67 | 0.32 (0.19–0.52) | < 0.001 | 0.32 (0.19–0.53) | < 0.001 |

| Yi | 19 | 0.80 | 1.04 (0.66–1.65) | 0.867 | 0.94 (0.59–1.50) | 0.801 |

| Dong | 15 | 0.63 | 0.63 (0.38–1.06) | 0.083 | 0.65 (0.39–1.09) | 0.104 |

| Tujia | 18 | 0.76 | 0.57 (0.36–0.92) | 0.021 | 0.78 (0.48–1.26) | 0.307 |

| Others | 24 | 1.01 | 1.06 (0.70–1.59) | 0.800 | 1.16 (0.77–1.76) | 0.481 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Peasant workers | 436 | 18.33 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Homemakers and unemployed persons | 57 | 2.40 | 2.25 (1.70–2.96) | < 0.001 | 1.85 (1.38–2.47) | < 0.001 |

| Students | 32 | 1.35 | 0.73 (0.51–1.05) | 0.088 | 1.12 (0.76–1.64) | 0.570 |

| Retired persons and cadres and staff | 15 | 0.63 | 1.46 (0.87–2.45) | 0.149 | 1.71 (1.01–2.90) | 0.044 |

| Others | 29 | 1.22 | 1.33 (0.91–1.93) | 1.326 | 1.40 (0.95–2.06) | 0.087 |

| Local registered residence | ||||||

| Yes | 471 | 19.81 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 98 | 4.12 | 1.87 (1.51–2.33) | < 0.001 | 2.38 (1.88–3.01) | < 0.001 |

| Source of patients | ||||||

| Clinical consultation | 254 | 10.68 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Referral | 223 | 9.38 | 1.28 (1.07–1.53) | 0.008 | 1.43 (1.19–1.72) | < 0.001 |

| Following up | 56 | 2.35 | 0.61 (0.45–0.81) | 0.001 | 0.62 (0.46–0.83) | 0.002 |

| Recommended for symptoms | 12 | 0.50 | 1.19 (0.66–2.12) | 0.563 | 0.73 (0.40–1.32) | 0.292 |

| Physical examinations | 5 | 0.21 | 0.40 (0.16–0.96) | 0.041 | 1.00 (0.41–2.46) | 0.998 |

| Others | 19 | 0.80 | 2.87 (1.80–4.58) | < 0.001 | 1.62 (1.00–2.62) | 0.049 |

| Clinical classification | ||||||

| Type I | 0 | 0.00 | Referent | |||

| Type II | 3 | 0.13 | 1,210,203.72.39 (0.00) | 0.996 | ||

| Type III | 566 | 23.80 | 4,035,016.57 (0.00) | 0.996 | ||

| Type IV | 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.000 | ||

| Type V | 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.000 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Etiological positivity | 520 | 21.87 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Etiological negative | 49 | 2.06 | 0.05 (0.03–0.06) | < 0.001 | 0.08 (0.06–0.11) | < 0.001 |

| Pure tuberculous pleurisy | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.979 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.980 |

| Others | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.991 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.991 |

| Severe cases | ||||||

| Yes | 199 | 8.37 | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 370 | 15.56 | 0.30 (0.25–0.36) | < 0.001 | 0.42 (0.35–0.50) | < 0.001 |

| Therapeutic category | ||||||

| Initial treatment | 301 | 12.66 | Referent | Referent | ||

| re-treated | 268 | 11.27 | 16.95 (14.36–19.99) | < 0.001 | 8.14 (6.84–9.69) | < 0.001 |

Discussions

We studied the variation trend, spatial distribution, and risk factor analysis of the five adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou. Guizhou is a typical karst landscape with a humid and rainy climate. Compared with the eastern and central regions, it is underdeveloped in terms of economy, transportation, culture and education level. In addition, the population of ethnic minorities in Guizhou accounts for a large proportion with 49 ethnic minorities. Because the lifestyle, living environment of many ethnic minorities are different from others, what's more, we don't know if there are some genetic differences between them that might affect the outcome, therefore, ethnic minorities are also included in our study as an important risk factor.

Among the five adverse outcomes of TB, except that the CR of adverse reactions showed a downward trend (P < 0.05), and the CR of lost to follow-up, treatment failed, died and switch to MDR showed an upward trend (Fig. 1), which indicated that the adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou were not satisfying and even worrying. The five adverse outcomes showed characteristics of spatial cluster, but the regions of spatial cluster were different. We can draw some conclusions from LISA diagram, the high-risk areas for adverse reaction of TB in Guizhou were mainly concentrated in Tongren city and Qiandongnan city (Fig. 3a). The spatial clustering of TB patients' loss of follow-up, treatment failure, and death were different, but there were also relevant and common evidences that revealed that the medical conditions in these areas and the living conditions of patients may need to be improved, because loss of follow-up, treatment failure, and death in TB patients are strongly related to patient compliance, living environment, family economic conditions, humanistic care and local medical conditions.The high-risk area for switch to MDR was mainly concentrated in Zunyi city (Fig. 3e). Compared with the regional ranking of TB incidence in Guizhou from 2013 to 20184, it shows that the regions with high rate of adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou were not only in those with high incidence, for example, Guiyang city had a low incidence of TB but high risk in died. It should be noticed by the relevant authorities.

Some studies have shown that poor economic conditions, poor medical services condition18, with diabetes29, old age and smoking will increase the risk of adverse reactions30, our study shows that women are more likely to have adverse reactions than men, Miao and Dong have a higher risk, while Buyi and Tujia have a lower risk. In addition, recommendation for symptoms, etiological negative, pure tuberculous pleurisy, middle-aged and elderly, retired persons and cadres and staffs, severe, re-treatment patients have a higher risk (Table 1).

Existing study31 have shown that the lost to follow-up of TB patients are significantly correlated with occupation, smoking, drinking, marital status, socioeconomic status, the study also found that although the drugs are provided freely, but there are many unfavorable factors for male patients, for example, low socioeconomic status, household debt and loss of income due to work and so on, which lead to them cannot be followed up during their treatment, in addition, the lost to follow up of patients are mainly young men and farmers32, Tola Habteyes Hailu's research results about the developing countries show that33 the main factors associated with lost to follow up and don't adherence to treatment are socioeconomic factors, including lack of transport costs, lack of social support and poor communication between patients and health care workers. Our study found that Buyi, Dong and Tujia have lower risk, while pure tuberculous pleurisy, severe and re-treatment have a higher risk (Table 2).

Age, household registration, occupation, source of patients, sputum smear results, and treatment type are the risk factors of treatment failed34, and the elderly, male, non-local, re-treatment, irregular treatment, delayed treatment and smoking will result in higher probability of Treatment failed26,35 (Table 3).

Age, gender, household registration, sputum smear results and treatment type are the risk factors of TB death34, while male, elderly, HIV-positive, etiological positive and re-treatment have a higher risk of death during anti-tuberculosis treatment36. Our study found that Dong, Tujia, retired persons and cadres and staffs have a lower risk, while students, middle-aged and elderly, referral, severe and re-treatment patients have a higher risk (Table 4).

Some studies have shown that TB patients with re-treatment and over 40 years old are more likely to develop MDR37. Our study shows that Miao and Buyi have a lower risk, while retired persons and cadres and staffs, middle-aged, referral, severe and retreated patients have a higher risk (Table 5).

Conclusions

Some important findings and conclusions are drawn from our study. The variation trend of entirely adverse outcomes of TB in Guizhou province is becoming increasingly serious. Spatial clusters exists in each of the five adverse outcomes, among which some regions were not with high incidence of TB, which should be noticed by relevant departments. There are significant differences among nationalities in the adverse outcomes of TB, which may be greatly related to the differences in life styles, living habits, living environment and physical conditions among different nationalities, and it is also impossible to exclude the influence of some unclear genes among different nationalities. In the process of patient diagnosis and treatment, timely monitoring and active intervention should be carried out for high-risk groups, including middle-aged and elderly patients, rural patients, floating patients, severe patients and retreated patients, which is of great significance for reducing the rate of adverse reactions, lost to follow-up, died and switch to MDR. focus on strengthening the whole-course treatment management and health education for these high-risk groups, which is very important to improve patients' treatment compliance, completing follow-up, completing treatment and curing.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ziyun Wang for his assistance in statistics and methodology, Dr. Wang is an associate professor of epidemiology at the School of Public Health, Guizhou Medical University.

Author contributions

J.Z. designed the study, extracted the data from all sources, he and X.M. performed the analyses and drafted the manuscript, J.T. reviewed the results of the paper's statistical analysis, F.H. and J.L. critically edited the manuscript.

Funding

Preliminary work project of Provincial Capital Construction of Guizhou Provincial Development and Reform Commission "Study on the Mode of Comprehensive Prevention and Control and Reduction of Disease Burden in High-epidemic Areas of Guizhou province" (2020-181-131).

Data availability

The data used in this study are freely available. All data generated and analysed during the course of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jian Zhou and Xiaoxue Ma.

Contributor Information

Feng Hong, Email: 519490967@qq.com.

Jinlan Li, Email: lijinlanpublic@126.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis Report 2015. World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Wang XL, Feng T, Fang CZ. Analysis of spatial-temporal distribution and risk factors of pulmonary tuberculosis in China, during 2008–2015. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018;147:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818002765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis Report 2018. World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou J, Chen HJ, Hong F, Li JL. Analysis on the characteristics of tuberculosis patients in Guizhou Province from 2013 to 2018. Mod. Prev. Med. 2020;47:1541–1546. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Xu CH, Wang ZY, Wang XM, Wang YH, Zhang H, et al. Investigation on the financial burden of tuberculosis patients in designated tuberculosis hospitals in China. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2019;5:559–564. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li WB, Li XX, Zhang H, Li RZ, Cheng J, Wang LX. Investigation on the status quo of medical security for non-drug-resistant tuberculosis patients in different regions of China. Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2012;13:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li CY, Cai XF, Yuan M. Analysis of mental health status and risk factors of pulmonary tuberculosis patients treated in our hospital in recent three years. Chin. Health Stat. 2019;36:267–269. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu T, Huang LJ, Yang JJ, Yao Z, Xiao H. Analysis of 308 cases of MDR-TB patients' mental health status and its risk factors. Chin. J. Defense Consum. 2020;42:366–371. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiang M, Cheng HZ, Da CZ, Ya HY. Analysis on spatial-temporal distribution characteristics of smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis in China, 2004–2015. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;80:836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal S, Nguyen DT, Teeter LD, Graviss EA. Spatial-temporal distribution of genotyped tuberculosis cases in a county with active transmission. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017;17:378. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2480-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu XF, Gou FX, Ren XW, Liu DP, Zheng YH, Wei KF, et al. Spatial-temporal specific incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis in Gansu, 2009–2013. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2015;36:465–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva MDAE. Spatial distribution of tuberculosis from 2002 to 2012 in a midsize city in Brazil. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3575-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeiffer DU, Robinson TP, Stevenson M, Stevens KB, Clements ACA. Spatial Analysis in Epidemiology. Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Xi Y, Ren F. Spatio-temporal distribution characteristics and trajectory similarity analysis of tuberculosis in Beijing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13:1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jafari-Koshki T, Arsang-Jang S, Raei M. Applying spatiotemporal models to study risk of smear-positive tuberculosis in Iran, 2001–2012. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2015;19:469–474. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulldorff M, Nagarwalla N. Spatial disease clusters: detection and inference. Stat. Med. 1995;14:799–810. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li XZ, Wang JF. A fast method for making candidate clusters in spatial scan statistic method. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2013; 15:505–511. Pulmonary Tuberculosis in the 7 Socioeconomic Regions and the 32 States of Mexico, 2000–2009. Arch. Bronconeumol. (English Edition) 2015;51:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2014.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anuj M, Pradeep D, Ajay D. Determinants of adverse treatment outcomes among patients treated under Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program in Wardha, India: case–control study. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2018;74:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshmukh PR, Mundra A, Dawale A. Social capital and adverse treatment outcomes of tuberculosis: a case-control study. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. Off. J. Int. Union Against Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017;21:941–946. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anuj M, Pradeep RD, Ajay D. Magnitude and determinants of adverse treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients registered under Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program in a Tuberculosis Unit, Wardha, Central India: a record-based cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2017;7:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babalik A, Kiziltas S, Gencer S, Kilicaslan Z. An investigation into the relationship between region specific quality of life and adverse tuberculosis treatment outcomes in Istanbul Turkey. Rev. Portuguesa Pneumol. 2014;20:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.rppneu.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kassa GM, Teferra AS, Wolde HF, Muluneh AG, Merid MW. Incidence andpredictors of lost to follow-up among drug-resistant tuberculosis patients at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective follow-up study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19:817. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4447-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leslie AE, Elizabeth DL, Tonya AM, Jessica E, Cynthia C, Botshelo K, et al. Investigating outcomes of adolescents and young adults (10–24 years of age) lost to follow-up from tuberculosis treatment in Gaborone, Botswana. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019;38:271–274. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bemba ELP, Bopaka RG, Ossibi-Ibara R, Toungou SN, Ossale-Abacka BK, Okemba-Okombi FH, et al. Predictive factors of lost to follow-up status during tuberculosis treatment in Brazzaville. Rev. Pneumol. Clin. 2017;73:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pneumo.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto K, Komukai J, Kasai S, Hirota S, Koda S, Terakawa K, Shimouchi A. Evaluation of risk factors for failed/defaulted on treatment outcomes of pulmonary tuberculosis in Osaka City. Kekkaku [Tuberculosis] 2014;89:593–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharareh R, Niakan K, Mahshid N, Xiao JZ. A logistic regression model to predict high risk patients to fail in tuberculosis treatment course completion. IAENG Int. J. Appl. Math. 2010;40:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juan JS-B. Mortality Trends and Risk of Dying From Pulmonary Tuberculosis in the 7 Socioeconomic Regions and the 32 States of Mexico, 2000–2009. Arch. Bronconeumol. (English Edition) 2015;51:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.03,020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Companion handbook to the WHO guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Report on Geneva: 2014, 17–20. [PubMed]

- 29.Jiang BF, Ma CC, Chen YG, Ba Y, Liu MD, Aliye A, et al. Analysis of adverse reaction rate and its risk factors of anti-tuberculosis drugs. Chin. J. Dis. Control. 2017;21:160–163. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y, Xie ZY, Zang LN, Du J, Liu YH, Li L. Analysis of factors risk adverse drug reactions in smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Chin. J. Zoonoses. 2016;32:1070–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aurora H, Kapoor S. Determinants of lost to follow up during treatment among tuberculosis patients in Delhi. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2016;5:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu TY, Wei SS, Liu FY, Cao YF, Gao F. Characteristics analysis of new smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients registered as missing in Guangxifrom 2008 to 2011. Chin. J. Dis. Control. 2013;17:900–903. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tola HH, Tol A, Shojaeizadeh D, Garmaroudi G. Tuberculosis treatment non-adherence and lost to follow up among TB patients with or without HIV in developing countries: a systematic review. Iran. J. Public Health. 2015;44:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang D, Wen J, Liu NQ, Ayinuer M, Qimanguli S, Hu X, et al. Factors affecting treatment outcomes of pulmonary tuberculosis in Xinjiang uygur population (article) Chin. Gen. Pract. 2019;22:1413–1418. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang JY, Zhong Q, Zhou L, Chen L, Chen WQ. Meta-analysis of factorsrisk tuberculosis treatment failure in China. Chin. J. Dis. Control. 2014;18:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie Y, Han J, Yu WL, Li J, Sun X. Analysis of the effect of short-range supervision on anti-tuberculosis treatment and the risk factors of death in patients with tuberculosis in Tianjin. Public Health China. 2020;36:126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang JJ, Zhou ML, Du YX, Chen C, Chen Z, Chen J, et al. Analysis of risk factors of drug-resistant/MDR-TB in Wuhan city. Chin. J. Dis. Control. 2017;21:164–167. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are freely available. All data generated and analysed during the course of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.