Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to examine the association between parenting, including the parent–child interaction and child maltreatment in the first grade (6–7 years old), and school refusal in the second (7–8 years old) and fourth (9–10 years old) grades among elementary school children in Japan.

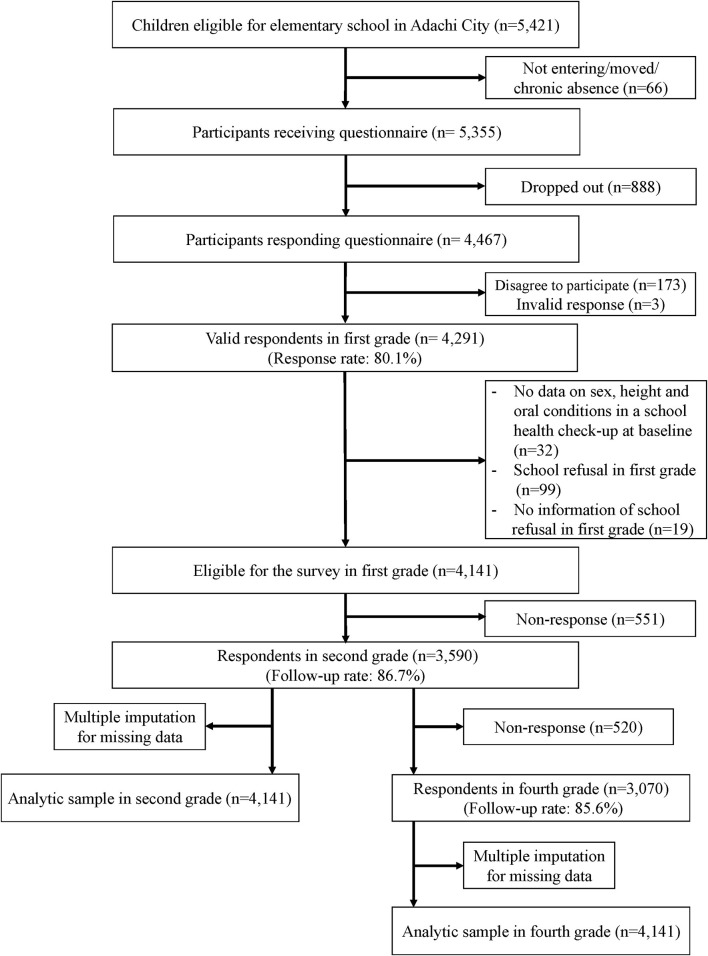

Methods: Data were from the Adachi Child Health Impact of Living Difficulty (A-CHILD) longitudinal study conducted in 2015, 2016, and 2018 in Adachi City, Tokyo, Japan. A questionnaire was distributed to all the first-grade school children (N = 5,355) in 2015. Of the total 4,291 valid children (response rate: 80.1%), 3,590 and 3,070 children were followed up to the second and fourth grades, respectively. Caregivers responded to the questionnaire on the parent–child interaction and child maltreatment, including neglect, physical abuse, and psychological abuse in the first grade and school refusal in the second and fourth grades. We conducted multiple imputation for missing data. Multivariate logistic regression model was used for this analysis adjusting for child mental health in the first grade and sociodemographic characteristics.

Results: Prevalence of school refusal was 1.8% (n = 64) in the second grade and 2% (n = 60) in the fourth grade. We found no association of the parent–child interaction and child maltreatment in the first grade and with school refusal in the second and fourth grades, respectively, after adjusting for covariates.

Conclusions: Parenting, such as the parent–child interaction and child maltreatment, may not be associated with school refusal among elementary school children. Further longitudinal research is needed to elucidate other factors, such as peer relationships and school environment, which can affect school refusal.

Keywords: school refusal, parenting, parent-child interaction, child maltreatment, mental health, prevention

Introduction

School refusal is one of the important school-related problems. School refusal is defined as child-motivated refusal to attend school or difficulties remaining in the classroom for an entire day with the presence of emotional upset, such as anxiety and depression (1, 2). An estimated 0.5–5% of children show school refusal in the United States (3, 4), Venezuela (5), and India (6). School refusal has negative impacts on the emotional and social development and academic performance in childhood (7–9) and can lead to psychiatric illnesses and occupational and marital problems in adulthood (10, 11). Hence, it is crucial to elucidate the risk factors for school refusal to prevent these adverse consequences.

Parenting may be associated with school refusal. As one form of parenting, the parent–child interaction plays an essential role in the socioemotional and educational development of children. In daily life, parents interact with their children in various ways: from communicating and doing activities together (e.g., playing and cooking) to getting involved in their education (e.g., helping their schoolwork and talking about school), which affects mental health and school performance of children. For example, previous studies reported that parent–child communication had beneficial effects on well-being of children (12) and fewer behavior problems (13). Moreover, cooking with children is associated with the responsibility and self-esteem (14). Research has also shown that the parental involvement in cooking activities evokes positive emotions and feeling in control (15) among children. Furthermore, the parental involvement in children's education outside school affects academic achievements and attitudes and the motivation toward school among children (16–19). Prior studies have shown a positive association of the parental involvement at home with their school performance and attendance among children (16, 20, 21). Research has also reported the association of less parental involvement at home with school attendance problems among children, such as truancy and dropped out (22, 23). Given the psychosocial and academic benefits of the parent–child interaction, it may function as one of the protective factors for school refusal among children. However, no published study so far examined the association between the parent–child interaction and school refusal.

As a deviant form of parenting, child maltreatment has adverse impacts on emotional and social development of children. Child maltreatment also causes psychosomatic symptoms, mental illness, low self-esteem, antisocial problems, and impaired self-regulation in children (24). Further, prior research has indicated an association between child maltreatment and school absenteeism among adolescents (25, 26). Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that child maltreatment could be a risk factor for school refusal. However, no studies have focused on the relationship between child maltreatment and school refusal. For preventive interventions for school refusal, there is a need to assess whether maltreated children have an increased risk of school refusal.

To date, few empirical studies of school refusal have been conducted in prospective designs. A longitudinal study is needed to investigate the relationships between potential risk factors and school refusal for causality. Moreover, according to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, the number of chronic school absenteeism, which can be linked to a negative outcome of school refusal, in the second, fourth, and sixth grades has increased by 1.5, 3.5, and 6.1 times, respectively, compared with the first grade (27). Accordingly, there is an urgent need to address this attendance problem and to identify risk and protective factors for school refusal before the problem gets worse for the prevention. The aim of this study was to examine the association between parenting and school refusal in a general population of elementary school children in Japan using a longitudinal dataset. We then focused on the impacts of the parent–child interaction and child maltreatment as the indicators of parenting in the first grade on school refusal in the second and fourth grades.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Data were from the Adachi Child Health Impact of Living Difficulty (A-CHILD) study conducted in 2015, 2016, and 2018 in Adachi City, Tokyo, Japan, which has 69 public elementary schools (28). In 2015, a self-reported questionnaire was distributed to all children in the first grade (6–7 years old) of all the elementary schools (n = 5,355, wave 1) in the city. Children took the questionnaire to home for their caregivers to fill out. The completed questionnaire was anonymously, but with the identification number, submitted in school (n = 4,467). A total of 4,291 caregivers gave informed consent (response rate: 80.1%). We excluded participants who had missing data at baseline (n = 32) on sex, height, and oral conditions in a school health check-up that all children in Adachi City are required to participate. Children who showed school refusal in the first grade and had no information about school refusal in the first grade were also excluded (n = 99 and 19, respectively). All the children (7–8 years old) were followed up in the second grade (N = 3,590, follow-up rate: 86.7%) in 2016 as wave 2. These children were followed up in the fourth grade (n = 3,070, follow-up: rate 85.6%) in 2018 as wave 3. A flow chart of the study participants is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants.

Measurements

Parenting: Parent-Child Interaction

The parent–child interaction was assessed based on the frequency of nine types of parental interaction with their children in the first grade as follows: helping the child with schoolwork, playing with the child through physical exercise, playing video games with the child, playing card games or role-playing games with the child, talking with the child about school life, talking with the child about the news, talking about TV shows with child, cooking with the child, and going out with the child. Caregivers rated score to each question using a scale of 0 = “seldom,” 1 = “once or twice per month,” 2 = “once or twice per week,” 3 = “three or four times per week,” and 4 = “almost every day. We summed the parent–child interaction scores (the Cronbach's alpha = 0.72) and categorized them into tertile (1: low, 2: middle, and 3: high).

Child Maltreatment

Child maltreatment, including neglect, physical abuse, and psychological abuse, in the first grade was assessed by nine items adopted from the 17 items of Japanese child maltreatment scale (α = 0.77) (29, 30). Neglect was assessed by three items: “shut the child outside,” “do not feed the child,” and “leave the child alone in the house at night.” Physical abuse was measured by two items: “hit the body of the child (buttocks, hand, head, or face)” and “beat the child.” Psychological abuse was measured by three items: “yell at the child,” “insult the child repeatedly,” and “have a big fight in front of the child.” We did not use the item “ignore the child” because it can be a part of parental discipline and is difficult to classify clearly as a type of child maltreatment. A four-point Likert scale for each question was used (1 = “often,” 2 = “sometimes,” 3 = “rarely,” and 4 = “not at all”), and the caregivers scored. The responses were dichotomized, referring to expert review based on the severity and frequency of child maltreatment in Japan (31). As for the items of “hit the body of the child” and “yell at the child” are relatively prevalent, the response of “often” was classified as a “yes” response, and the responses “sometimes,” “rarely,” and “not at all” were classified as a “no” response. As for the items of “insult the child repeatedly” and “have a big fight in front of the child,” the responses “often” and “sometimes” were classified as a “yes” response, and the responses “rarely” and “not at all” as a “no” response. As for the items “beat the child,” “lock the child outside,” “do not feed the child,” and “leave the child alone in the house at night,” the responses “often,” “sometimes,” and “rarely” were classified as a “yes” response, whereas the response “not at all” as a “no” response. Then, when any items in each category of child maltreatment had a “yes” response once or more, we defined the category as “Yes” and dichotomized (1 = “Yes” and 0 = “No”).

School Refusal

Caregivers were asked whether their child was absent from school and, if so, the number of the days during the past 6 months since the beginning of the second and fourth grades, respectively. The caregivers also were asked the reason for school absence using the following categories: (1) illness or injury, (2) family reasons, (3) he/she did not want to go to school, and (4) other reasons. Then, we defined the response of three and the absence cases for more than 1 day as school refusal, and the response was dichotomized (1 = Yes, 0 = No).

Child Mental Health

The Emotional and behavior problems of children in the first grade, that is, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer problems, were assessed using the scales of total difficulties score from the Japanese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (32). The caregivers rated the score of the SDQ. The reliability and validity of the SDQ in Japanese children have been reported in previous research (33, 34).

In addition, the resilience of children in the first grade was assessed using the Children's Resilient Coping Scale (CRCS) (35). The scale consisted of eight items with high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.80). The caregivers rated the resilience and coping behavior of their child from 0 (never) to 4 (very frequently). The score of the CRCS was calculated by summing up the score of the eight items and ranged from 0 to 32; a higher total score indicated a higher resilience.

Covariates

The sex of a child (boy or girl), birth order (no siblings, eldest, youngest, or middle), the marital status of the caregiver (married or single/others), and household income (<3.0, 3.0– <6.0, 6.0– <10.0, ≥10.0 million JPY; 110 JPY ≈ 1 USD) were used as covariates in the analysis. The mental health of the caregiver was assessed using the Japanese version of the Kessler 6 (K6) (36). It consists of six items about depression and anxiety rated on a five-point Likert scale. The total score of the six items was calculated (0–24); a higher score indicated a higher level of psychological distress. A score of 5–12 in the K6 was defined as the moderate psychological distress, and that of ≥13 was as the severe psychological distress (37).

Statistical Analysis

We applied the multiple imputation approach under the assumption of the missing at random to minimize potential bias due to missing information. We generated 100 imputed datasets using the multiple imputation by chained equations procedure (MICE). The results were synthesized based on the Rubin's rule (38). Multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for school refusal in the second and fourth grades, respectively. The following models were constructed: Model 1 was adjusted for the sex of a child, the marital status of the caregiver, birth order, household income, and K6 of the caregiver; in Model 2, all parenting variables (parent–child interaction with child and child maltreatment) were added to the Model 1; and Model 3 added child mental health (the total difficulties score of the SDQ and the score of the CRCS) to the Model 2; and Model 4 added school refusal in the second grade to the Model 3 (only in the analysis of school refusal in the fourth grade). For sensitivity analysis, we further investigated the associations of parenting with school refusal by the number of school refusal days. We used STATA version 15.0 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) for all analyses.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the National Center for Child Health and Development (Study ID: 1147) and Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Study ID: M2016-284).

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants in the first grade classified by school refusal status in the second grade. The prevalence of school refusal in the second grade was 1.8% (n = 64). As for the sex of a child, boys refused school more than girls in the second grade (56.3 and 43.8%, respectively). As for parenting, more children of school refusal showed the lower tertile of the parent–child interaction than those of non-school refusal (45.3 vs. 36.0%; p = 0.32). Similarly, regarding child maltreatment, more children of school refusal in the second grade experienced neglect (17.2 vs. 13.1%; p = 0.35), physical abuse (21.9 vs. 11.9%; p = 0.018), and psychological abuse (43.8 vs. 29.9%; p = 0.020) than children of non-school refusal.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the first grade by school refusal status in the second grade (N = 4,141).

| Total |

No school refusal (N = 3,526) |

School refusal (N = 64) |

Missing (N = 551) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Boys | 2,121 | 51.2 | 1,804 | 51.2 | 36 | 56.3 | 281 | 51.0 |

| Girls | 2,020 | 48.8 | 1,722 | 48.8 | 28 | 43.8 | 270 | 49.0 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 3,675 | 88.8 | 3,176 | 90.1 | 55 | 85.9 | 444 | 80.6 |

| Single/others | 359 | 8.7 | 268 | 7.6 | 9 | 14.1 | 82 | 14.9 |

| Missing | 107 | 2.6 | 82 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 25 | 4.5 |

| Birth order | ||||||||

| No siblings | 866 | 20.9 | 738 | 20.9 | 15 | 23.4 | 113 | 20.5 |

| Eldest (having younger sibling) | 1,315 | 31.8 | 1,130 | 32.1 | 23 | 35.9 | 162 | 29.4 |

| Youngest (having elder sibling) | 1,512 | 36.5 | 1,286 | 36.5 | 18 | 28.1 | 208 | 37.8 |

| Middle (having both elder and younger sibling) | 448 | 10.8 | 372 | 10.6 | 8 | 12.5 | 68 | 12.3 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Household income (million yen) | ||||||||

| <3.0 | 460 | 11.1 | 365 | 10.4 | 10 | 15.6 | 85 | 15.4 |

| 3.0– <6.0 | 1,661 | 40.1 | 1,413 | 40.1 | 31 | 48.4 | 217 | 39.4 |

| 6.0– <10.0 | 1,256 | 30.3 | 1,103 | 31.3 | 15 | 23.4 | 138 | 25.1 |

| ≥10.0 | 354 | 8.6 | 310 | 8.8 | 4 | 6.3 | 40 | 7.3 |

| Missing | 410 | 9.9 | 335 | 9.5 | 4 | 6.3 | 71 | 12.9 |

| K6 | ||||||||

| <5 | 2,927 | 70.7 | 2,525 | 71.6 | 34 | 53.1 | 368 | 66.8 |

| 5– <13 | 977 | 23.6 | 829 | 23.5 | 21 | 32.8 | 127 | 23.1 |

| ≥13 | 182 | 4.4 | 136 | 3.9 | 9 | 14.1 | 37 | 6.7 |

| Missing | 55 | 1.3 | 36 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 3.5 |

| Parenting | ||||||||

| Parent–child interaction | ||||||||

| Low | 1,523 | 36.8 | 1,269 | 36.0 | 29 | 45.3 | 225 | 40.8 |

| Middle | 1,441 | 34.8 | 1,257 | 35.7 | 19 | 29.7 | 165 | 30.0 |

| High | 1,145 | 27.7 | 981 | 27.8 | 16 | 25.0 | 148 | 26.9 |

| Missing | 32 | 0.8 | 19 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 2.4 |

| Neglect | ||||||||

| No | 3,543 | 85.6 | 3,035 | 86.1 | 53 | 82.8 | 455 | 82.6 |

| Yes | 547 | 13.2 | 460 | 13.1 | 11 | 17.2 | 76 | 13.8 |

| Missing | 51 | 1.2 | 31 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 3.6 |

| Physical abuse | ||||||||

| No | 3,575 | 86.3 | 3,071 | 87.1 | 50 | 78.1 | 454 | 82.4 |

| Yes | 513 | 12.4 | 421 | 11.9 | 14 | 21.9 | 78 | 14.2 |

| Missing | 53 | 1.3 | 34 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 3.5 |

| Psychological abuse | ||||||||

| No | 2,818 | 68.1 | 2,436 | 69.1 | 36 | 56.3 | 346 | 62.8 |

| Yes | 1,264 | 30.5 | 1,054 | 29.9 | 28 | 43.8 | 182 | 33.0 |

| Missing | 59 | 1.4 | 36 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 4.2 |

| Child mental health | ||||||||

| SDQ | ||||||||

| Total difficulties score (mean, SD) | 9.8 (5.3) | – | 9.7 (5.2) | – | 12.1 (6.5) | – | – | – |

| CRCS | ||||||||

| Total score (mean, SD) | 21.2 (4.9) | – | 21.3 (4.8) | – | 18.8 (5.7) | – | – | – |

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants in the first grade classified by school refusal status in the fourth grade. The prevalence of school refusal in the fourth grade was 2.0% (n = 60). As for the sex of a child, boys accounted for 61.7% of school refusal cases in the fourth grade. As for parenting, more children of school refusal showed the lower tertile of the parent–child interaction (40.0 vs. 35.5%; p = 0.49). Similarly, regarding child maltreatment, children of school refusal showed more neglect (16.7 vs. 13.1%; p = 0.44) and physical abuse (13.3 vs. 11.5%; p = 0.68), compared with children of non-school refusal. Psychological abuse was observed more in children of non-school refusal than in those of school refusal (30.1 vs. 26.7%; p = 0.57). The proportion of children refusing to go to school in the second grade was 15.0% among school refusal group in the fourth grade, which was higher than children of non-school refusal (15 vs. 1.3%; p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the first grade by school refusal status in the fourth grade (N = 4,141).

| Total |

No school refusal (N = 3,010) |

School refusal (N = 60) |

Missing (N = 1,071) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Boys | 2,121 | 51.2 | 1,512 | 50.2 | 37 | 61.7 | 572 | 53.4 |

| Girls | 2,020 | 48.8 | 1,498 | 49.8 | 23 | 38.3 | 499 | 46.6 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 3,675 | 88.8 | 2,750 | 91.4 | 44 | 73.3 | 881 | 82.3 |

| Single/Others | 359 | 8.7 | 195 | 6.5 | 13 | 21.7 | 151 | 14.1 |

| Missing | 107 | 2.6 | 65 | 2.2 | 3 | 5.0 | 39 | 3.6 |

| Birth order | ||||||||

| No siblings | 866 | 20.9 | 622 | 20.7 | 16 | 26.7 | 228 | 21.3 |

| Eldest (having younger sibling) | 1,315 | 31.8 | 980 | 32.6 | 17 | 28.3 | 318 | 29.7 |

| Youngest (having elder sibling) | 1,512 | 36.5 | 1,102 | 36.6 | 21 | 35.0 | 389 | 36.3 |

| Middle (having both elder and younger sibling) | 448 | 10.8 | 306 | 10.2 | 6 | 10.0 | 136 | 12.7 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Household income (million yen) | ||||||||

| <3.0 | 290 | 9.6 | 8 | 13.3 | 162 | 15.1 | 460 | 11.1 |

| 3.0– <6.0 | 1,224 | 40.7 | 23 | 38.3 | 414 | 38.7 | 1,661 | 40.1 |

| 6.0– <10.0 | 950 | 31.6 | 16 | 26.7 | 290 | 27.1 | 1,256 | 30.3 |

| ≥10.0 | 274 | 9.1 | 4 | 6.7 | 76 | 7.1 | 354 | 8.6 |

| Missing | 272 | 9.0 | 9 | 15.0 | 129 | 12.0 | 410 | 9.9 |

| K6 | ||||||||

| <5 | 2,927 | 70.7 | 2,174 | 72.2 | 34 | 56.7 | 719 | 67.1 |

| 5–13 | 977 | 23.6 | 708 | 23.5 | 17 | 28.3 | 252 | 23.5 |

| ≥13 | 182 | 4.4 | 103 | 3.4 | 8 | 13.3 | 71 | 6.6 |

| Missing | 55 | 1.3 | 25 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.7 | 29 | 2.7 |

| Parenting | ||||||||

| Parent–child interaction | ||||||||

| Low | 1,523 | 36.8 | 1,069 | 35.5 | 24 | 40.0 | 430 | 40.2 |

| Middle | 1,441 | 34.8 | 1,069 | 35.5 | 23 | 38.3 | 349 | 32.6 |

| High | 1,145 | 27.7 | 857 | 28.5 | 13 | 21.7 | 275 | 25.7 |

| Missing | 32 | 0.8 | 15 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 17 | 1.6 |

| Neglect | ||||||||

| No | 3,543 | 85.6 | 2,590 | 86.1 | 50 | 83.3 | 903 | 84.3 |

| Yes | 547 | 13.2 | 395 | 13.1 | 10 | 16.7 | 142 | 13.3 |

| Missing | 51 | 1.2 | 25 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 26 | 2.4 |

| Physical abuse | ||||||||

| No | 3,575 | 86.3 | 2,639 | 87.7 | 52 | 86.7 | 884 | 82.5 |

| Yes | 513 | 12.4 | 347 | 11.5 | 8 | 13.3 | 158 | 14.8 |

| Missing | 53 | 1.3 | 24 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 29 | 2.7 |

| Psychological abuse | ||||||||

| No | 2,818 | 68.1 | 2,083 | 69.2 | 44 | 73.3 | 691 | 64.5 |

| Yes | 1,264 | 30.5 | 897 | 29.8 | 16 | 26.7 | 351 | 32.8 |

| Missing | 59 | 1.4 | 30 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 29 | 2.7 |

| Child mental health | ||||||||

| SDQ | ||||||||

| Total difficulties score (mean, SD) | 9.6 (5.2) | – | 9.5 (5.1) | – | 10.9 (5.6) | – | – | – |

| CRCS | ||||||||

| Total score (Mean, SD) | 21.3 (4.8) | – | 21.4 (4.8) | – | 20.3 (5.3) | – | – | – |

| School refusal in the second grade | ||||||||

| No | 3,526 | 85.2 | 2,971 | 98.7 | 51 | 85.0 | 504 | 47.1 |

| Yes | 64 | 1.6 | 39 | 1.3 | 9 | 15.0 | 16 | 1.5 |

| Missing | 551 | 13.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 551 | 51.5 |

Table 3 shows the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis for school refusal in the second grade after multiple imputation. In the crude model, the parent–child interaction in the first grade was not associated with school refusal in the second grade. Physical abuse and psychological abuse in the first grade showed association with school refusal in the second grade (OR: 2.10, 95% CI: 1.16–3.82 and OR 1.82, 95% CI: 1.11–2.98, respectively). No association between neglect in the first grade and school refusal in the second grade was observed. In Model 1, the parent–child interaction and each category of child maltreatment in the first grade showed no association with school refusal in the second grade, after adjusting for the sex of the child, the marital status of the caregiver, siblings, income, and K6 of the caregiver. As for child mental health, the total difficulties score of the SDQ in the first grade was associated with school refusal in the second grade (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.10). The score of the CRCS in the first grade showed a significant inverse association with school refusal in the second grade (OR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.88–0.97). In both Model 2, including all parenting variables, and Model 3, including all parenting and child mental health variables, the parent–child interaction and child maltreatment in the first grade were not associated with school refusal in the second grade. In Model 3, the total difficulties score of the SDQ in the first grade showed no association with school refusal in the second grade. As for the CRCS score in the first grade, the association with school refusal in the second grade remained significant (OR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.87–0.99).

Table 3.

Association between parenting in the first grade and school refusal in the second grade after multiple imputation.

| Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Parenting | ||||||||

| Parent–child interaction | ||||||||

| Low | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – |

| Middle | 0.67 | 0.38–1.19 | 0.71 | 0.40–1.26 | 0.72 | 0.40–1.29 | 0.82 | 0.46–1.49 |

| High | 0.71 | 0.38–1.32 | 0.78 | 0.42–1.46 | 0.81 | 0.43–1.52 | 1.05 | 0.54–2.05 |

| Neglect | ||||||||

| No | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – |

| Yes | 1.34 | 0.70–2.59 | 1.12 | 0.57–2.21 | 1.01 | 0.51–2.02 | 0.99 | 0.50–1.99 |

| Physical abuse | ||||||||

| No | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – |

| Yes | 2.10* | 1.16–3.82 | 1.55 | 0.83–2.90 | 1.38 | 0.70–2.71 | 1.29 | 0.65–2.55 |

| Psychological abuse | ||||||||

| No | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – |

| Yes | 1.82* | 1.11–2.98 | 1.41 | 0.84–2.37 | 1.25 | 0.71–2.19 | 1.14 | 0.64–2.00 |

| Child mental health | ||||||||

| SDQ: Total difficulties score | 1.08*** | 1.04–1.13 | 1.05* | 1.01–1.10 | – | – | 1.01 | 0.95–1.06 |

| CRCS: Total score | 0.90*** | 0.86–0.94 | 0.92** | 0.88–0.97 | – | – | 0.93* | 0.87–0.99 |

p < 0.001,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

OR, odds ratio.

Model 1: adjusted for sex, birth order, the marital status of the caregiver, household income, and K6 of the caregiver.

Model 2: added all parenting variables to Model 1.

Model 3: added child mental health (the SDQ and the CRCS) to Model 2.

Table 4 shows the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis for school refusal in the fourth grade after multiple imputation. In both crude and Model 1, there was no association between the parent–child interaction and each category of child maltreatment in the first grade and school refusal in the fourth grade. Similarly, Models 2 and 3 showed no association of the parent–child interaction and all categories of child maltreatment in the first grade with school refusal in the fourth grade. As for child mental health, in the crude model, the total difficulties score of the SDQ in the first grade was associated with school refusal in the fourth grade (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.11). In Models 1 and 3, the association of total difficulties score of the SDQ and school refusal showed no significance. The score of the CRCS in the first grade was not associated with school refusal in the fourth grade in all models. Furthermore, in Model 4, children with school refusal at the second grade showed 11 times greater risk of school refusal at the fourth grade, independent of covariates.

Table 4.

Association between parenting in the first grade and school refusal in the fourth grade after multiple imputation.

| Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Parenting | ||||||||||

| Parent–child interaction | ||||||||||

| Low | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – |

| Middle | 0.95 | 0.54–1.69 | 1.07 | 0.59–1.92 | 1.02 | 0.57–1.86 | 1.07 | 0.59–1.96 | 1.07 | 0.57–2.01 |

| High | 0.71 | 0.35–1.44 | 0.83 | 0.40–1.72 | 0.80 | 0.38–1.66 | 0.85 | 0.40–1.82 | 0.83 | 0.41–1.68 |

| Neglect | ||||||||||

| No | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – |

| Yes | 1.24 | 0.63–2.45 | 1.03 | 0.51–2.07 | 1.12 | 0.55–2.28 | 1.09 | 0.53–2.23 | 1.07 | 0.50–2.32 |

| Physical abuse | ||||||||||

| No | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – |

| Yes | 1.15 | 0.53–2.48 | 0.78 | 0.34–1.79 | 0.98 | 0.41–2.37 | 0.94 | 0.39–2.27 | 0.84 | 0.35–2.02 |

| Psychological abuse | ||||||||||

| No | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – | ref | – |

| Yes | 0.85 | 0.47–1.54 | 0.60 | 0.32–1.15 | 0.59 | 0.30–1.17 | 0.56 | 0.28–1.11 | 0.56 | 0.27–1.14 |

| Child mental health | ||||||||||

| SDQ: total difficulties score | 1.05* | 1.01–1.11 | 1.02 | 0.96–1.07 | – | – | 1.02 | 0.96–1.09 | 1.03 | 0.94–1.08 |

| CRCS: Total score | 0.96 | 0.91–1.00 | 0.98 | 0.93–1.04 | – | – | 0.99 | 0.93–1.05 | 1.01 | 0.94–1.08 |

| School refusal in the second grade | ||||||||||

| No | ref | – | ref | – | – | – | – | – | ref | – |

| Yes | 13.68*** | 6.39–29.27 | 10.99*** | 4.84–24.91 | – | – | – | – | 11.7*** | 5.02–27.4 |

p < 0.001,

p < 0.05.

OR, odds ratio.

Model 1: adjusted for sex, birth order, the marital status of the caregiver, household income, and K6 of the caregiver.

Model 2: added all parenting variables to Model 1.

Model 3: added child mental health (the SDQ and the CRCS) to Model 2.

Model 4: added school refusal in the second grade to Model 3.

The sensitivity analysis investigating the associations of parenting with school refusal by the number of school refusal days showed that parenting was not associated with school refusal regardless of the number of the days (see Supplementary Tables 1–5).

Discussion

In this study, we examined whether parenting was prospectively associated with school refusal among elementary school children. We found no associations of both parent–child interaction and child maltreatment in the first grade with school refusal in the second and fourth grades. Our results suggest that the parent–child interaction may not have a preventive effect on later school refusal among elementary school children, and child maltreatment may not be an independent risk factor for school refusal.

To our knowledge, no empirical studies have examined the association between parenting and school refusal using a longitudinal dataset. Previous research reported that school refusal was associated with the mental health of the caregiver (39) and socioeconomic status (11) as home environmental factors. Then, our models in this study assessed the effect of parenting on school refusal, adjusted for individual factors including the mental health of children and home environmental factors, together with the marital status of caregiver and siblings affecting the child development (40–42). Accordingly, our findings suggest that other factors, that is, school-related factors, may be more directly associated with school refusal among elementary school children rather than individual, parental, and home environmental factors. Indeed, prior studies have indicated that school-related problems, such as relationships with peers and teachers, school climate, and academic achievement, have an association with school refusal, which are known as risk factors (39, 43, 44). Thus, school-related problems may be more likely to be associated with school refusal for elementary school children. Further longitudinal research is needed to investigate the potential causal relationship between school-related problems and school refusal.

Moreover, we found no significant association between the parent–child interaction and school refusal, which renders this study the first to report the effect of the parent–child interaction on school refusal among elementary school children. We focused on the extent of the parent–child interaction, using the measurement variable of the interaction, which broadly incorporated various types of parental interaction at home. Accordingly, our finding suggests that the extent and types of the parent–child interaction may not contribute to the prevention of later school refusal. However, exactly how parents interact with their children in daily activities, that is, the quality of parent–child interaction or parental attitudes, was not assessed in this study. Prior research has indicated that improving the quality of parent–child interaction, which is applied in therapy, has preventive effects on behavior problems of children, such as aggressive behavior (45) and emotional problems, such as depression and anxiety (46, 47), which are the frequent comorbid conditions for school refusal. Further, as an example of the interaction, previous studies have reported that the positive parent–child communication is associated with fewer depressive symptoms (48), behavior problems (13), life satisfaction (49), and development of problem-solving strategies (14). Hence, given the beneficial effects, the quality of parent–child interaction may affect school refusal. However, whether there is an association between the quality of parental interaction with children and school refusal remains unclear. Future studies focusing on the effect of the quality of the interaction on school refusal are required. These may allow to fully understand the association between parent–child interaction and school refusal.

Our study revealed that child maltreatment, including neglect, physical abuse, and psychological abuse, had no association with later school refusal. A number of previous studies have shown that child maltreatment impairs the emotional and social development of children (50), and maltreated children have more relationship problems with their peers at school, such as peer rejection (51, 52). In addition, child maltreatment is negatively associated with academic performance (26, 53). These findings suggest that child maltreatment may indirectly increase the risk of school refusal, mediated by these peer-relationship problems, and lower academic performance. Moreover, maltreated children tend to have difficulties in school adjustment (54). However, in this study, we did not find an association between child maltreatment and school refusal. Although the exact reason remains unclear, one possible explanation is that school may function as a place for maltreated children to escape from home, similar to third places for maltreated children (55). Further research is needed to longitudinally evaluate the association between child maltreatment and school refusal with a qualitative design revealing the mechanisms.

There are several limitations in this study. First, school refusal, parental involvement, and child maltreatment were assessed by the caregiver, which may give rise to common method bias. Second, for the child maltreatment measurement, the scale was not validated, though it was based on self-report scales that have been widely used in Japan (56). And we did not assess traditional parenting styles, i.e., authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful parenting (57, 58), due to limited space in the questionnaire. Moreover, we assessed only the quantity of parent–child interaction, but not for the quality of parent–child interaction, which is more important for the child development (59, 60). Third, although this longitudinal study showed a high response and followed-up rate, response bias should be considered. Given the characteristics of the outcome in this study, parents with children who refused to go to school may be unwilling to participate in the survey. To address the potential bias, we carried out using multiple imputation. Fourth, parental demographic factors might influence measurements of child mental health. Prior research reported that the total difficulties mean score of the SDQ for children of non-responding parents showed higher than that for children of responding parents (61). Thus, further, teacher-rating may help to assess child mental health more objectively. Fifth, we did not assess the physical problems and predisposition of children. Previous studies reported that oral health problems were associated with school absences and academic performance (62). Further, children with autism spectrum traits have an increased risk of school refusal (63). These factors may affect school refusal among children. Sixth, we lacked information on the reasons for school refusal, including the school-related problems in this study. Seventh, we did not use validated scales to assess for school refusal such as the School Refusal Assessment Scale (SRAS-R) (64, 65).

Despite these limitations, our current longitudinal study demonstrated no association between parenting and school refusal among elementary school refusal in population-based data. The empirical findings of this study provide a new understanding of the mechanisms of school refusal and the functions of individual, parental, and home environmental factors. Future research should explore the underlying causes of school refusal and the types of parenting that could play a preventive role in school refusal among children.

In conclusion, our study identified that the parent–child interaction and child maltreatment in the first grade were not associated with school refusal in the second and fourth grades among elementary school children in Japan. Further investigation is strongly recommended to better understand the complex association between the risk and protective factors and school refusal.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Tokyo Medical and Dental University Ethics Commitee. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

YF contributed to conception, design, analysis, and interpretation and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. SD and AI contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. MO contributed to conception, design, and data acquisition and critically revised the manuscript. TF contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to the staff members and central office of Adachi City Hall for conducting the survey. We would like to thank everyone who participated in the surveys. In particular, we would also like to thank Mayor Yayoi Kondo, Mr. Syuichiro Akiu, and Ms. Yuko Baba of Adachi City Hall, who contributed significantly to completion of this study.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by a Health Labor Sciences Research Grant, Comprehensive Research on Lifestyle Disease from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (H27-Jyunkankito-ippan-002), Research of Policy Planning and Evaluation from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (H29-Seisaku-Shitei-004), Innovative Research Program on Suicide Countermeasures (IRPSC), and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16H03276, 16K21669, 17J05974, 17K13245, 19K19310, 19K14029, 19K19309, 19K20109, 19K14172, 19J01614, 19H04879, and 20K13945), St. Luke's Life Science Institute Grants, and the Japan Health Foundation Grants.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2021.640780/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Berg I. Absence from school and mental health. Br J Psychiatry. (1992) 161:154–66. 10.1192/bjp.161.2.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychol Sci Practice. (1996) 3:339–54. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00087.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke AE, Silverman WK. The prescriptive treatment of school refusal. Clin Psychol Rev. (1987) 7:353–62. 10.1016/0272-7358(87)90016-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egger HL, Costello EJ, Angold A. School refusal and psychiatric disorders: a community study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2003) 42:797–807. 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046865.56865.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granell de Aldaz E, Vivas E, Gelfand DM, Feldman L. Estimating the prevalence of school refusal and school-related fears. A Venezuelan sample. J Nervous Mental Dis. (1984) 172:722–9. 10.1097/00005053-198412000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair MK, Russell PS, Subramaniam VS, Nazeema S, Chembagam N, Russell S, et al. ADad 8: School Phobia and Anxiety Disorders among adolescents in a rural community population in India. Indian J Pediatr. (2013) 80 (Suppl. 2):S171–4. 10.1007/s12098-013-1208-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll HCM. The effect of pupil absenteeism on literacy and numeracy in the primary school. School Psychol Int. (2010) 31:115–30. 10.1177/0143034310361674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christle CA, Jolivette K, Nelson CM. School characteristics related to high school dropout rates. Remed Spec Educ. (2007) 28:325–39. 10.1177/07419325070280060201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Last CG, Strauss CC. School refusal in anxiety-disordered children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. (1990) 29:31–5. 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flakierska-Praquin N, Lindström M, Gillberg C. School phobia with separation anxiety disorder: a comparative 20- to 29-year follow-up study of 35 school refusers. Compreh Psychiatry. (1997) 38:17–22. 10.1016/S0010-440X(97)90048-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kearney CA. School Refusal Behavior in Youth: A Functional Approach to Assessment and Treatment. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; (2001). p. xiii, 265-xiii. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bireda AD, Pillay J. Perceived parent–child communication and well-being among Ethiopian adolescents. Int J Adol Youth. (2018) 23:109–17. 10.1080/02673843.2017.1299016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson TM, Cardemil EV. Parent-child communication and parental involvement in Latino adolescents. J Early Adol. (2009) 29:99–121. 10.1177/0272431608324480 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olfert MD, Hagedorn RL, Leary MP, Eck K, Shelnutt KP, Byrd-Bredbenner C. Parent and school-age children's food preparation cognitions and behaviors guide recommendations for future interventions. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2019) 51:684–92. 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Horst K, Ferrage A, Rytz A. Involving children in meal preparation. Effects on food intake. Appetite. (2014) 79:18–24. 10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan X, Chen M. Parental involvement and students' academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Educat Psychol Rev. (2001) 13:1–22. 10.1023/A:1009048817385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-DeHass AR, Willems PP, Holbein MFD. Examining the relationship between parental involvement and student motivation. Educat Psych Rev. (2005) 17:99–123. 10.1007/s10648-005-3949-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spera C. A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achievement. Educat Psychol Rev. (2005) 17:125–46. 10.1007/s10648-005-3950-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Darling N. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Dev. (1992) 63:1266–81. 10.2307/1131532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Englund MM, Luckner AE, Whaley GJL, Egeland B. Children's achievement in early elementary school: longitudinal effects of parental involvement, expectations, and quality of assistance. J Educat Psychol. (2004) 96:723–30. 10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoover-Dempsey KV, Battiato AC, Walker JM, Reed RP, DeJong JM, Jones KP. Parental involvement in homework. Educat Psychol. (2001) 36:195–209. 10.1207/S15326985EP3603_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNeal Jr RB. Parental involvement as social capital: differential effectiveness on science achievement, truancy, and dropping out. Soc Forces. (1999) 78:117–44. 10.1093/sf/78.1.117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaughn MG, Maynard BR, Salas-Wright CP, Perron BE, Abdon A. Prevalence and correlates of truancy in the US: results from a national sample. J Adol. (2013) 36:767–76. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schatz JN, Smith LE, Borkowski JG, Whitman TL, Keogh DA. Maltreatment risk, self-regulation, and maladjustment in at-risk children. Child Abuse Negl. (2008) 32:972–82. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagborg JM, Berglund K, Fahlke C. Evidence for a relationship between child maltreatment and absenteeism among high-school students in Sweden. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 75:41–9. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slade EP, Wissow LS. The influence of childhood maltreatment on adolescents' academic performance. Econ Educ Rev. (2007) 26:604–14. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology . Jidou seito no mondai koudou futoukoutou seitoshidoujou no shokadai ni kansuru chousa (in Japanese) (2019). Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/seitoshidou/1302902.htm (accessed October 1, 2020).

- 28.Ochi M, Isumi A, Kato T, Doi S, Fujiwara T. Adachi child health impact of living difficulty (A-CHILD) study: Research protocol and profiles of participants. J Epidemiol. (2021) 31:77–89. 10.2188/jea.JE20190177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tokunaga M, Ohara M, Kayama M, Yoshimura K, Mitsuhashi J, Senoo E. Survey of child maltreatment among general population in Greater Tokyo. Kosei no Shihyo. (2000) 47:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe Y, Kayama M, Sagami A, Senoo E, Ohara M. TM. Child abuse and risk factors: a survey in tokyo metropolitan area. Japan Bull Soc Psychiatry. (2002) 10:239–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isumi A, Fujiwara T, Nawa N, Ochi M, Kato T. Mediating effects of parental psychological distress and individual-level social capital on the association between child poverty and maltreatment in Japan. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 83:142–50. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (1997) 38:581–6. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moriwaki A, Kamio Y. Normative data and psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire among Japanese school-aged children. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2014) 8:1. 10.1186/1753-2000-8-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibata Y, Okada K, Fukumoto R, Nomura K. Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher forms of the Japanese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Brain Dev. (2015) 37:501–7. 10.1016/j.braindev.2014.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doi S, Fujiwara T, Ochi M, Isumi A, Kato T. Association of sleep habits with behavior problems and resilience of 6- to 7-year-old children: results from the A-CHILD study. Sleep Med. (2018) 45:62–8. Epub 2018/04/24. 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2008) 17:152–8. 10.1002/mpr.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K, Yanagida K, Kawakami N. Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2011) 65:434–41. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. (2011) 30:377–99. 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2001) 35:822–6. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00955.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee D, McLanahan S. Family structure transitions and child development:instability, selection, and population heterogeneity. Am Sociol Rev. (2015) 80:738–63. 10.1177/0003122415592129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magnuson K, Berger LM. Family structure states and transitions: associations with children's well-being during middle childhood. J Marr Family. (2009) 71:575–91. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00620.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Whiteman SD. Sibling relationships and influences in childhood and adolescence. J Marr Family. (2012) 74:913–30. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01011.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingul JM, Nordahl HM. Anxiety as a risk factor for school absenteeism: what differentiates anxious school attenders from non-attenders? Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2013) 12:25. 10.1186/1744-859X-12-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kearney CA. School absenteeism and school refusal behavior in youth: a contemporary review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2008) 28:451–71. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas R, Abell B, Webb HJ, Avdagic E, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Parent-child interaction therapy: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2017) 140:e20170352. 10.1542/peds.2017-0352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joan L, Luby MD, Deanna M. A randomized controlled trial of parent-child psychotherapy targeting emotion development for early childhood depression. Am J Psychiatry. (2018) 175:1102–10. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18030321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lieneman CC, Brabson LA, Highlander A, Wallace NM, McNeil CB. Parent–child interaction therapy: current perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2017) 10:239–56. 10.2147/PRBM.S91200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ren Z, Zhou G, Wang Q, Xiong W, Ma J, He M, et al. Associations of family relationships and negative life events with depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0219939–e. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cava MJ, Buelga S, Musitu G. Parental communication and life satisfaction in adolescence. Spanish J Psychol. (2014) 17:E98. 10.1017/sjp.2014.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shields AM, Cicchetti D, Ryan RM. The development of emotional and behavioral self-regulation and social competence among maltreated school-age children. Dev Psychopathol. (1994) 6:57. 10.1017/S0954579400005885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anthonysamy A, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Peer status and behaviors of maltreated children and their classmates in the early years of school. Child Abuse Neglect. (2007) 31:971–91. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Dev. (2001) 72:549–68. 10.1111/1467-8624.00296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eckenrode J, Laird M, Doris J. School performance and disciplinary problems among abused and neglected children. Dev Psych. (1993) 29:53. 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.53 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lim Y, Lee O. Relationships between parental maltreatment and adolescents' school adjustment: mediating roles of self-esteem and peer attachment. J Child Family Studies. (2017) 26:393–404. 10.1007/s10826-016-0573-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fujiwara T, Doi S, Isumi A, Ochi M. Association of existence of third places and role model on suicide risk among adolescent in japan: results from A-CHILD study. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:1131. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.529818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujiwara T, Kasahara M, Tsujii H, Okuyama M. Association of maternal developmental disorder traits with child mistreatment: a prospective study in Japan. Child Abuse Neglect. (2014) 38:1283–9. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baumrind D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet Psychol Monogr. (1967) 75:43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maccoby E, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction, In: Hetherington EM, Mussen PH. editors. Handbook of Child Psychology Socialization, Personality, and Social Development, Vol. 4. New York, NY: Wiley; (1983). p. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR. The importance of parenting during early childhood for school-age development. Dev Neuropsych. (2003) 24:559–91. Epub 2003/10/17. 10.1207/S15326942DN2423_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams LR, Degnan KA, Perez-Edgar KE, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Pine DS, et al. Impact of behavioral inhibition and parenting style on internalizing and externalizing problems from early childhood through adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2009) 37:1063–75. 10.1007/s10802-009-9331-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, Treffers PDA, Goodman R. Dutch version of the Strengths andDifficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Europ Child Adol Psychiatry. (2003) 12:281–9. 10.1007/s00787-003-0341-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson SL, Vann WF, Jr., Kotch JB, Pahel BT, Lee JY. Impact of poor oral health on children's school attendance and performance. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:1900–6. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.200915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Munkhaugen E, Gjevik E, Pripp AH, Sponheim E, Diseth T. School refusal behaviour: are children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder at a higher risk? Res Autism Spectr Disorders. (2017) 41–42:31–8. 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kearney C, Silverman W. Measuring the function of school refusal behavior: the school refusal assessment scale. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (1993) 22:85–96. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kearney CA. Identifying the function of school refusal behavior: a revision of the school refusal assessment scale. J Psychopath Behav Assess. (2002) 24:235–45. 10.1037/10426-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.