Abstract

Objectives

The diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is often delayed, which affects various clinical outcomes. This study examined the real-world situation of patients with AS during diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

Data were obtained from 26 tertiary care hospitals in Korea using a self-report questionnaire. The questionnaire assessed symptoms, pain, extra-articular manifestations, the initial pattern of pain before diagnosis, factors leading to delayed referral to rheumatology, time until receiving an AS diagnosis, comorbid diseases, treatment status, and disease education needs.

Results

Between September and October 2019, 1012 patients with AS completed the survey. Of these, 75.8% were men and 51.8% were in their 30s or 40s. Median disease duration was 76 months. The median time to diagnosis with AS was 12 months. When pain occurred, the medical departments most frequently visited first were orthopedic (61.5%) and rheumatology (18.7%) departments. The likelihood of the first visit being to the orthopedic department and the frequency of biologics use increased with the disease duration. The rates of uveitis, depressed mood, and comorbid diseases were higher in the group with delayed diagnosis.

Conclusions

Physicians should be aware of subtypes of AS that take longer to diagnose and comorbid diseases in the real-world clinical setting.

Keywords: Real-world setting, self-survey, ankylosing spondylitis, comorbid disease, Korea, clinical outcome

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is subtype of spondyloarthritides (SpA), including non-radiographic axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis.1 These diseases are all characterized by inflammatory back pain and extra-articular manifestations, including enthesitis, uveitis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease.2 AS is associated with decreased quality of life (QoL) and work productivity, as well as pain, fatigue, morning stiffness, disability, and cardiovascular comorbidities.3–5 Therefore, delayed diagnosis in patients with AS can lead to social burdens owing to an inability to maintain daily work or to receive adequate and timely treatment. Diagnosing AS is often challenging as back pain is common among the general population, the disease progresses insidiously, there are no specific biomarkers, and referral to a rheumatologist is often delayed. Patients frequently consult with non-rheumatologists in the early stages of the disease.6 Moreover, social diversity influences patient decisions; therefore, improving the current situation is essential for better long-term management of AS.7 In this study, we (a) analyzed the baseline demographic characteristics of patients, pain before diagnosis, the first medical institution visited, and time until receiving a diagnosis of AS; (b) analyzed clinical characteristics according to disease duration and time to diagnosis; and (c) examined the relationship between clinical characteristics and comorbid diseases using a self-report survey.

Methods

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional descriptive design was used. Participants were patients with AS aged 18 years or older attending a rheumatology outpatient clinic at 26 tertiary care hospitals in the Republic of Korea. All patients were diagnosed with AS by their treating rheumatologist and met the 1984 modified New York criteria.8 Data were collected from patients with AS who completed a self-report questionnaire between September and October 2019. This questionnaire was completed only once and personal information was not recorded. The questionnaire included items on sex, age, disease duration, treatment status, first medical department visited, initial diagnosis, time until receiving a diagnosis of AS, pain characteristics, other symptoms, extra-articular manifestations, comorbid medical diseases, and disease education requirements. Completed surveys were reviewed by expert members of the Korean Rheumatology Society.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to analyze variables with a normal distribution, and nonparametric tests were used for data that were not normally distributed. Basic demographic and descriptive data are presented descriptively using median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous data and frequency with percentage for categorical data. Clinical characteristics were compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney U test to compare each pair of group medians, and the chi-square test was used for testing trends between groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test and post-hoc analysis (Mann–Whitney U test) were used to compare clinical parameters among the three groups. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with the risk of comorbid diseases, and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated. For all analyses, p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics committee approval

This study was approved by the relevant institutional review board/ethics committee (IRB/EC) of Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, which reviewed the verbal consent form, study protocol, and potential risks and benefits to participants (IRB file no. SCHUH 2020-02-008). Because the survey was conducted voluntarily without matching personal information in clinical practice, its retrospective use was approved without the need for informed consent by the IRB/EC.

Results

Baseline demographics and characteristics of patients with AS

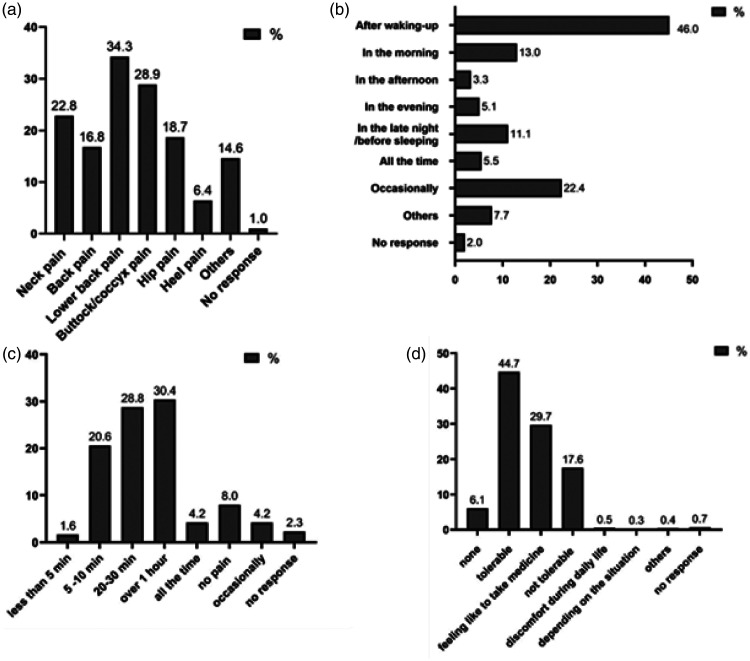

A total of 1012 patients with AS completed a self-report questionnaire survey between September and October 2019. Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic data of all patients. Among respondents, 75.8% were men, 51.8% were in their 30s or 40s, and the median duration of disease was 76 months. Most patients received hospital treatment only (89.3%); 57.6% indicated that they were receiving injections, but only 30.6% reported that they were using biologics. Hospital treatment refers to treatment in a medical institution as recognized by government agencies. On experiencing symptoms, the medical departments most frequently visited first were the orthopedics department (61.5%) and rheumatology department (18.7%). Only 38.1% of patients were diagnosed with AS after the initial hospital visit, and the median time to receiving an accurate diagnosis of AS was 12 months. The first type of pain to develop was most frequently lower back pain (34.3%), followed by buttock/coccyx pain (28.9%). Pain most often occurred immediately after waking in the morning (46.0%) and lasted for over 1 hour (30.4%), but 44.7% of patients reported that they could tolerate their pain (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Basic patient demographic data obtained in self-report questionnaire (N = 1012).

| Frequency (n) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 767 | 75.8 |

| Female | 235 | 23.2 |

| No response | 10 | 1.0 |

| Age | ||

| 10s | 7 | 0.7 |

| 20s | 153 | 15.1 |

| 30s | 254 | 25.1 |

| 40s | 270 | 26.7 |

| 50s | 201 | 19.9 |

| 60s | 80 | 7.9 |

| Over 70 years | 31 | 3.1 |

| No response | 16 | 1.6 |

| Median disease duration (months)a | 76 (36–144) | |

| Recent treatment(s) (multiple responses allowed) | ||

| Oral medication | 583 | 57.6 |

| Injection | 556 | 54.9 |

| Exercise | 57 | 5.6 |

| Other | 12 | 1.2 |

| No response | 41 | 4.1 |

| Additional treatments | ||

| Hospital treatment only | 904 | 89.3 |

| Other (manual physical therapy, and so on) | 82 | 8.1 |

| Both | 3 | 0.3 |

| No response | 23 | 2.3 |

| First department visited (multiple responses allowed) | ||

| Orthopedics | 622 | 61.5 |

| Rheumatology | 189 | 18.7 |

| Neurosurgery | 73 | 7.2 |

| Oriental medicine | 61 | 6.0 |

| Pain medicine | 46 | 4.5 |

| Rehabilitation medicine | 31 | 3.1 |

| Family medicine | 8 | 0.8 |

| Ophthalmology | 12 | 1.2 |

| General medicine | 3 | 0.3 |

| Other | 31 | 3.1 |

| No response | 10 | 1.0 |

| First diagnosis (multiple responses allowed) | ||

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 387 | 38.1 |

| Herniated disc | 154 | 15.2 |

| Non-specific pain | 130 | 12.8 |

| Hip arthropathy | 117 | 11.6 |

| Chronic myalgia | 52 | 5.1 |

| Low back pain owing to poor posture | 62 | 6.1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 25 | 2.5 |

| Gout | 9 | 0.9 |

| Plantar fasciitis | 8 | 0.8 |

| Uveitis | 5 | 0.5 |

| Other | 88 | 8.7 |

| No response | 15 | 1.5 |

| Biologics used | ||

| Yes | 310 | 30.6 |

| No | 202 | 20.0 |

| Unsure | 347 | 34.3 |

| No response | 153 | 15.1 |

| Median time to diagnosis (months)a | 12 (3–48) | |

| Time to diagnosis | ||

| Less than 1 year | 504 | 49.8 |

| 1–2 years | 107 | 10.6 |

| 2–3 years | 81 | 8.0 |

| 3–4 years | 30 | 3.0 |

| 4–5 years | 47 | 4.6 |

| 5–6 years | 16 | 1.6 |

| More than 6 years | 152 | 15.0 |

| No response | 75 | 7.4 |

| Comorbid diseases (multiple responses allowed) | ||

| Hypertension | 209 | 20.7 |

| Dyslipidemia | 142 | 14.0 |

| Insomnia | 88 | 8.7 |

| Diabetes | 64 | 6.3 |

| Depression | 50 | 4.9 |

| Acute coronary syndrome (angina, MI) | 28 | 2.8 |

| Hepatitis B | 17 | 1.8 |

| Renal insufficiency | 14 | 1.4 |

| Other | 117 | 11.6 |

aMedian (interquartile range). Chi-square test was used for analysis.

MI, myocardial infarction.

Figure 1.

Types and characteristics of pain described by patients with ankylosing spondylitis as the initial symptom (N = 1012). (a) Site of pain, (b) time of day when pain occurs, (c) duration of pain, (d) severity of pain.

Clinical characteristics according to disease duration and time until diagnosis

The median time to diagnosis was longer in the group with a disease duration of more than 5 years, as compared with patients who had a shorter disease duration (12.5, IQR 3.25–60 vs. 12, IQR 3–36 months), p = 0.003). The probability of being diagnosed with AS within 1 year was significantly lower in the group with a disease duration over 5 years (47.7% vs. 55.6%, p = 0.01). The proportion of patients aged 40 years or older was higher in the group with disease duration over 5 years, as was the rate of biologics use (43.2% vs. 28.7%, p < 0.001) and the proportion who first visited the orthopedics department (65.9% vs. 59.3%, p = 0.04) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with AS, by disease duration.

|

Disease duration, n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 years | >5 years | Total | p-value | |

| Sexa | ||||

| Male | 298 (73.8) | 413 (81.5) | 711 (78.0) | 0.005** |

| Female | 106 (26.2) | 94 (18.5) | 200 (22.0) | |

| Age (years)b | ||||

| Less than 40 | 220 (55.0) | 165 (32.8) | 385 (42.6) | <0.001** |

| Over 40 | 180 (45.0) | 338 (67.2) | 518 (57.4) | |

| Biologics usedc | ||||

| Yes | 98 (28.7) | 188 (43.2) | 286 (36.8) | <0.001** |

| No | 93 (27.2) | 94 (24.6) | 187 (24.1) | |

| Unsure | 151 (44.2) | 153 (35.2) | 304 (39.1) | |

| Time to diagnosis (months)# | 12 (3–36) | 12.5 (3.25–60) | 12 (3–48) | 0.003** |

| Time to diagnosisd | ||||

| ≤1 year | 225 (55.6) | 242 (47.7) | 467 (53.9) | 0.010* |

| 1–2 years | 41 (10.1) | 57 (11.2) | 98 (10.6) | 0.621 |

| 2–3 years | 26 (6.4) | 48 (9.5) | 74 (8.5) | 0.102 |

| 3–4 years | 12 (3.0) | 14 (2.8) | 26 (3.0) | 0.837 |

| 4–5 years | 16 (4.0) | 28 (5.5) | 44 (5.1) | 0.284 |

| 5–6 years | 5 (1.2) | 10 (2.0) | 15 (1.7) | 0.394 |

| More than 6 years | 58 (14.3) | 85 (16.8) | 143 (16.5) | 0.341 |

| First department visited (multiple responses allowed) | ||||

| Orthopedics | 240 (59.3) | 334 (65.9) | 622 (62.9) | 0.040* |

| Rheumatology | 70 (17.3) | 86 (17) | 156 (17.1) | 0.898 |

| Neurosurgery | 38 (9.4) | 30 (5.9) | 68 (7.5) | 0.048* |

| Oriental medicine | 33 (8.1) | 25 (4.9) | 58 (6.4) | 0.048* |

| Pain medicine | 21 (5.2) | 20 (3.9) | 41 (4.5) | 0.369 |

| Rehabilitation medicine | 15 (3.7) | 14 (2.8) | 29 (3.2) | 0.420 |

| Family medicine | 3 (0.7) | 5 (1.0) | 8 (0.9) | 1.000 |

| Ophthalmology | 5 (1.2) | 5 (1.0) | 10 (1.1) | 0.758 |

| General medicine | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1.000 |

| Other | 9 (2.2) | 10 (2.0) | 19 (2.1) | 0.793 |

#Values analyzed using Mann–Whitney U or chi-square test. Values are median (IQR).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005.

Based on results in a911, b903, c777, d867 patients.

Clinical factors were compared among three groups, distinguished according to the time until AS diagnosis: within 1 year, 1 to 5 years, and more than 5 years. The prevalence of longer disease duration (p < 0.005), proportion of patients aged over 40 years (p < 0.001), and proportion of patients with a herniated disc (p < 0.001) or low back pain owing to poor posture (p = 0.001) as the first diagnosis was significantly higher in the group with more than 5 years to diagnosis. By contrast, in the group with a diagnosis made within 1 year, AS was significantly more often the first diagnosis (p < 0.001). Among other symptoms and extra-articular manifestations, the incidence rates of uveitis (p < 0.001) and depressed mood (p = 0.004) were significantly higher in the group with a time until diagnosis of more than 5 years. The frequency of comorbid diseases differed among the groups and increased with longer time to receiving a diagnosis of AS (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical factors according to time to diagnosis.

| Variables |

Time to diagnosis, n (%) |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within 1 year (n = 504) | 1–5 years (n = 265) | Over 5 years (n = 168) | Total (n = 937) | ||

| Sex (male) n (%) | 386 (77.7) | 201 (76.4) | 19 (77.2) | 716 (77.2) | 0.829 |

| Age >40 years | 246 (49.6) | 156 (60.2) | 130 (77.8) | 532 (57.7) | <0.001** |

| Disease duration (months)#,a | 72 (29–132) | 95.5 (41–180) | 96 (30–180) | 76 (36–144) | <0.005** |

| ≤5 years | 225 (48.2) | 95 (39.3) | 63 (39.9) | 383 (44.2) | 0.024* |

| >5 years | 242 (51.8) | 147 (60.7) | 95 (60.1) | 484 (55.8) | |

| Pain site (multiple responses allowed) | |||||

| Neck | 103 (20.4) | 62 (23.4) | 45 (26.8) | 210 (22.4) | 0.077 |

| Back | 73 (14.5) | 47 (17.7) | 38 (22.6) | 158 (16.9) | 0.014* |

| Lower back | 173 (34.3) | 95 (35.8) | 51 (30.4) | 319 (34.0) | 0.494 |

| Buttock/coccyx | 126 (25.0) | 93 (35.1) | 48 (28.6) | 267 (28.5) | 0.094 |

| Hip | 87 (17.3) | 52 (19.6) | 38 (22.6) | 177 (18.9) | 0.116 |

| Heel | 35 (6.9) | 19 (7.2) | 7 (4.2) | 61 (6.5) | 0.291 |

| Other | 88 (17.5) | 31 (11.7) | 17 (10.1) | 136 (14.5) | 0.007** |

| First diagnosis (multiple responses allowed) | |||||

| AS | 232 (45.8) | 67 (25.3) | 45 (26.8) | 344 (36.7) | <0.001** |

| Herniated disc | 59 (11.7) | 50 (18.9) | 40 (23.8) | 149 (15.9) | <0.001** |

| Not specific | 59 (11.7) | 43 (16.2) | 22 (13.1) | 124 (13.2) | 0.348 |

| Hip arthropathy | 53 (10.5) | 31 (11.7) | 23 (13.7) | 107 (11.4) | 0.263 |

| Chronic myalgia | 22 (4.4) | 22 (8.3) | 8 (4.8) | 52 (5.5) | 0.388 |

| Low back pain owing to poor posture | 18 (3.6) | 24 (9.1) | 18 (10.7) | 60 (6.4) | <0.001** |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 8 (1.6) | 11 (4.2) | 3 (1.8) | 22 (2.3) | 0.417 |

| Gout | 6 (1.2) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.0) | 0.226 |

| Plantar fasciitis | 5 (1.0) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.9) | 0.324 |

| Uveitis | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.8) | 5 (0.5) | 0.103 |

| Other | 46 (9.1) | 23 (8.7) | 13 (7.7) | 80 (8.5) | 0.588 |

| Symptoms and extra-articular manifestations (multiple responses allowed) | |||||

| Fatigue | 290 (57.5) | 168 (63.4) | 106 (63.1) | 564 (60.2) | 0.113 |

| Myalgia | 182 (36.1) | 120 (45.3) | 69 (41.1) | 371 (39.6) | 0.081 |

| Arthralgia | 179 (35.5) | 115 (43.4) | 56 (33.3) | 350 (37.4) | 0.825 |

| Depressed mood | 111 (22.0) | 74 (27.9) | 58 (34.5) | 243 (25.9) | 0.001** |

| Weight loss | 39 (7.7) | 21 (7.9) | 10 (6.0) | 70 (7.5) | 0.528 |

| Uveitis | 106 (21.0) | 69 (26.0) | 65 (38.7) | 240 (25.6) | <0.001** |

| Skin rash | 51 (10.1) | 34 (12.8) | 24 (14.3) | 109 (11.6) | 0.109 |

| Oral ulcer | 29 (5.8) | 21 (7.9) | 14 (8.3) | 64 (6.8) | 0.180 |

| Diarrhea, abdominal pain | 42 (8.3) | 23 (8.7) | 18 (10.7) | 83 (8.9) | 0.388 |

| Anterior chest pain | 88 (17.5) | 57 (21.5) | 37 (22.0) | 182 (19.4) | 0.125 |

| Pain in Achilles tendon | 83 (16.5) | 38 (14.3) | 27 (16.1) | 148 (15.8) | 0.733 |

| Dyspnea | 14 (2.8) | 17 (6.4) | 7 (4.2) | 38 (4.1) | 0.153 |

| Comorbid diseases | 218 (43.3) | 135 (50.9) | 101 (60.1) | 454 (48.5) | <0.001** |

#Kruskal–Wallis test or chi-square test was used to compare the three groups. Values are median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated. Comorbid diseases include those listed in Table 1.

*p<0.05, **p<0.005.

aSignificant difference between groups within 1 year and 1 to 5 years with Mann–Whitney U test.

AS, ankylosing spondylitis.

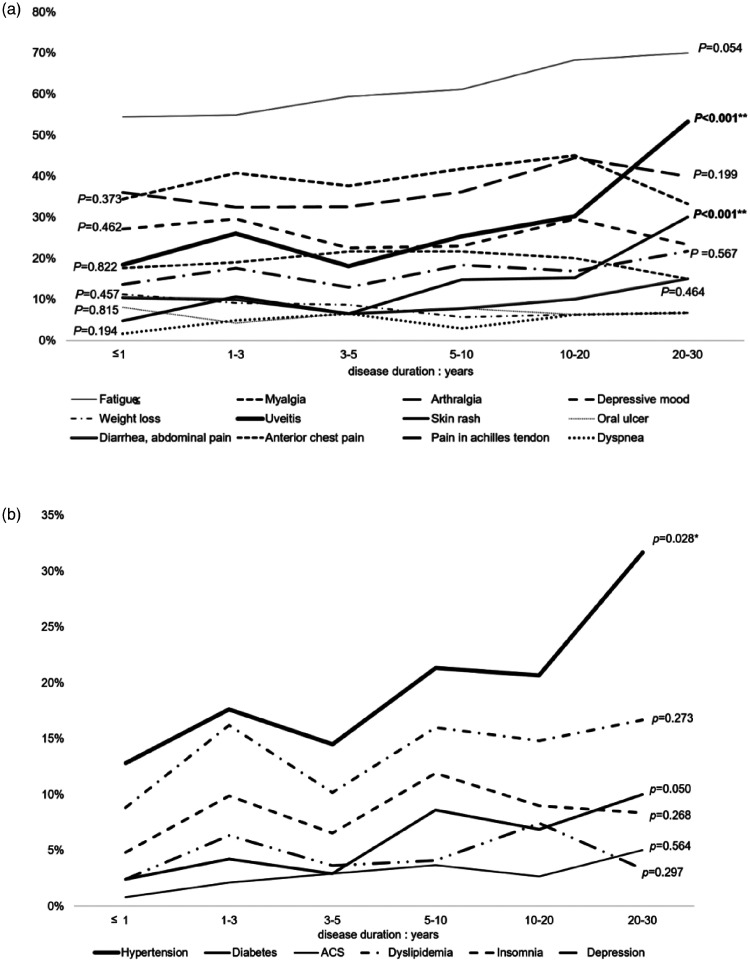

Relationship among accompanying clinical characteristics and comorbid diseases

The presence or absence of comorbid diseases was based on the results of the patient questionnaires. Patients were judged to have comorbid diseases when they took medicine or underwent related procedures. The most commonly reported comorbid diseases were hypertension (20.7%), dyslipidemia (14.0%), insomnia (8.7%), and diabetes (6.3%). The prevalence of a greater likelihood of extra-articular manifestations and comorbid diseases was increased with disease duration (Figure 2). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, comorbid diseases were more prevalent in those aged over 40 years (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Associations with disease duration. (a) Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations and (b) comorbid diseases.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for comorbid diseases in patients with AS.

|

Comorbid disease |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | Hypertension | ACS | Dyslipidemia | Diabetes mellitus | Insomnia | Depression |

| OR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Sex (female) | 0.520 (0.311–0.871)* | 0.249 (0.053–1.167) | 0.814 (0.479–1.383) | 0.644 (0.263–1.573) | 1.155 (0.628–2.124) | 2.368 (1.038–5.404)* |

| Disease duration (months) | 1.000 (0.998–1.002) | 0.998 (0.993–1.003) | 0.998 (0.997–1.001) | 1.003 (1.000–1.006)* | 0.999 (0.996–1.002) | 1.004 (0.997–1.005) |

| Over age 40 years | 4.447 (2.756–7.175)* | 6.015 (1.206–30.00)* | 6.617 (3.460–12.65)* | 3.263 (1.166–9.135)* | 1.763 (0.943–3.295) | 1.499 (0.614–3.662) |

| Hypertension | – | 4.288 (1.692–10.867)* | 2.068 (1.310–3.266)* | 3.316 (1.734–6.344)* | 0.910 (0.455–1.821) | 1.126 (0.439–2.888) |

| ACS | 3.735 (1.465–9.521)* | – | 2.245 (0.906–5.565) | 1.248 (0.380–4.098) | 0.261 (0.255–8.833) | 2.846 (0.669–12.107) |

| Dyslipidemia | 2.055 (1.300–3.250)* | 2.252 (0.894–5.671) | – | 2.642 (1.374–5.080)* | 1.410 (0.707–2.813) | 1.144 (0.433–3.028) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 3.282 (1.735–6.210)* | 1.875 (0.582–6.048) | 2.717 (1.431–5.157)* | – | 1.221 (0.436–3.420) | 1.277 (0.371–2.568) |

| Insomnia | 0.969 (0.478–1.961) | 0.253 (0.042–1.538) | 1.385 (0.684–2.806) | 1.426 (0.525–3.878) | – | 4.535 (2.020–10.185)* |

| Depression | 1.031 (0.419–2.537) | 3.153 (0.686–14.48) | 1.049 (0.413–2.663) | 1.873 (0.551–6.370) | 4.179 (1.876–9.310)* | – |

| Hepatitis B | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.501 (0.255–8.833) | 0.000 |

| Renal impairment | 0.765 (0.136–4.302) | 6.987 (0.443–110.31) | 2.157 (0.437–10.647) | 1.977 (0.224–17.456) | 9.010 (2.099–38.679)* | 2.622 (0.470–14.635) |

| Fatigue | 1.182 (0.793–1.760) | 0.573 (0.200–1.637) | 0.952 (0.603–1.502) | 0.924 (0.477–1.791) | 1.839 (0.933–3.626) | 0.946 (0.371–2.568) |

| Myalgia | 0.976 (0.662–1.438) | 1.975 (0.790–4.939) | 1.116 (0.723–1.725) | 2.073 (1.097–3.917)* | 1.329 (0.767–2.305) | 1.392 (0.628–3.086) |

| Arthralgia | 0.675 (0.455–1.002) | 0.929 (0.359–2.406) | 0.780 (0.492–1.235) | 0.922 (0.477–1.781) | 1.553 (0.887–2.718) | 1.047 (0.459–2.385) |

| Depressive mood | 0.914 (0.570–1.464) | 1.426 (0.482–4.214) | 1.111 (0.664–1.858) | 0.872 (0.385–1.974) | 3.031 (1.717–5.352)* | 6.820 (2.800–16.611)* |

| Weight loss | 2.274 (0.977–5.291) | 1.000 (0.218–4.590) | 0.934 (0.405–2.156) | 1.026 (0.327–1.410) | 1.951 (0.946–4.024) | 1.645 (0.625–4.331) |

| Uveitis | 1.255 (0.801–1.876) | 1.229 (0.461–3.272) | 1.351 (0.858–2.130) | 0.679 (0.327–1.410) | 0.701 (0.373–1.315) | 0.777 (0.321–1.878) |

| Skin rash | 0.923 (0.533–1.599) | 2.633 (0.881–7.872) | 1.118 (0.615–2.032) | 1.093 (0.268–3.105) | 1.526 (1.792–2.938) | 0.981 (0.394–2.444) |

| Oral ulcer | 1.230 (0.576–2.628) | 0.166 (0.013–2.109) | 1.141 (0.532–2.446) | 0.913 (0.268–3.105) | 1.808 (0.835–3.913) | 1.581 (0.541–4.618) |

| Diarrhea, abdominal pain | 1.459 (0.759–2.805) | 0.616 (0.111–3.400) | 0.522 (0.214–1.270) | 0.156 (0.019–1.276) | 1.808 (0.835–3.913) | 2.055 (0.763–5.535) |

| Anterior chest pain | 1.194 (0.742–1.920) | 1.306 (0.446–3.818) | 1.413 (0.833–2.396) | 0.740 (0.312–1.756) | 0.715 (0.368–1.391) | 1.815 (0.781–4.218) |

| Pain in Achilles tendon | 0.513 (0.297–0.886)* | 1.279 (0.424–3.857) | 1.316 (0.779–2.223) | 2.288 (1.091–4.798)* | 1.433 (0.772–2.659) | 0.744 (0.302–1.830) |

| Dyspnea | 0.819 (0.297–2.256) | 3.276 (0.649–16.527) | 0.526 (0.154–1.793) | 0.615 (0.093–4.055) | 0.649 (0.205–2.058) | 2.779 (0.951–8.126) |

*Significant differences are in bold text.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome, OR, odds ratio, CI, confidence interval.

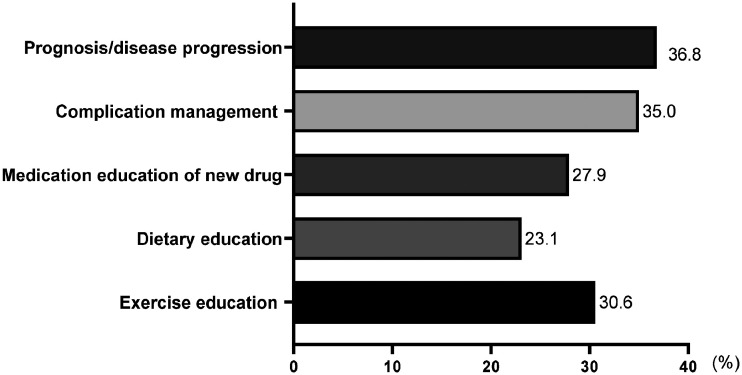

Education needs of patients with AS

In addition to usual clinical care, 437 of 974 respondents (44.9%) suggested the need for additional education, including information on disease progression or prognosis (36.8%), coping with complications during treatment (35.0%), and exercise (30.6%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Education wanted by patients with ankylosing spondylitis in the outpatient clinic (multiple responses allowed).

Discussion

The success of biologics for treating patients with AS has been demonstrated in numerous randomized controlled clinical trials, and tolerability has been documented in actual clinical practice.9 However, the treatment is unsatisfactory in many patients and transfer to a specialist is often delayed in the real-world setting.10 Early treatment of AS is important for slowing disease progression, and timely therapy provided by a rheumatologist can improve clinical outcomes.6 The time to receiving an AS diagnosis is the time from the initial symptoms to the initiation of therapy. In this study, the duration of the disease was defined as the period from the initial symptoms to the present or until the end of all treatments. Although a delay in the diagnosis and treatment of AS cannot be correlated with causing a specific comorbidity, it is known that such delays can cause progression of AS and can more often cause extra-articular manifestations. In the Korean medical system, in general, patients first receive treatment at a primary medical institution and are then referred to a secondary medical institution, depending on the severity of their disease. However, it is important for patients to select the appropriate department, in consideration of their symptoms, as they can visit a secondary hospital directly or can meet with a specialist in a primary medical institution. Most medical expenses are covered by the national insurance, and it is relatively easy to visit a hospital. The diagnosis of AS is commonly delayed because back pain, which is the primary symptom of AS, affects nearly all adults at some point in their lifetime.11,12 Time is needed to recognize symptoms, including specific pain characteristics and the relationship with extra-articular manifestations.13,14 In our study, there was no significant difference in the time to receiving a diagnosis between patients who complained of specific lower back pain and those who did not. However, there was a significant difference among patients with any back pain in a non-specific location: 14.5% of cases were diagnosed within 1 year; 17.7% were diagnosed within 1 to 5 years; and 22.6% were diagnosed after more than 5 years (p = 0.004). If the back pain is not in the lower back, it can take more time to diagnose AS.

The median time to diagnosis was 12 months, and this tended to be longer in the group with a disease duration of more than 5 years versus up to 5 years duration (12.5, IQR 3.25–60 vs. 12, IQR 3–36 months), p = 0.003). Although patients with a disease duration less than 5 years had a shorter delay to diagnosis, earlier diagnosis is still preferable. The medical system in the Republic of Korea is well organized and there have been many improvements for patients seeking rheumatologists. Nevertheless, orthopedic clinics were the most frequent department visited first by patients with AS, especially those with a disease duration of more than 5 years versus up to 5 years (65.9% vs. 59.3%, p = 0.040). Because we used a self-report instrument in our survey, it is difficult to confirm the accuracy of reporting regarding diagnoses and treatment patterns in terms of whether the first medical department visited was rheumatology or a non-rheumatology provider.6 A future study should further examine the actual behavior of patients, which could inform patient management.15,16 A seamless referral system should be the goal, through improving physician and patient education.

The median duration of disease in the 1012 patients was 76 (36–144) months, and 16.5% of patients had a disease duration of more than 6 years (Table 2). Although 64.5% of patients had a disease duration of less than 2 years, the proportion of patients with comorbid diseases was high, at 48.5% (Table 4). AS is a chronic inflammatory disorder with skeletal and systemic manifestations. Onset is usually at an early age and imposes a heavy burden on patients and society.17 The burden on individual patients with AS is not limited to health care costs associated with controlling disease activity but also encompasses costs associated with managing extra-articular manifestations, comorbidities, and disability.18,19 According to data of the National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort, a Korean population-based cohort with submitted medical claims between 2002 and 2013, 28% of patients with AS experienced at least one extra-articular manifestation.9,20 The impact of AS on mortality has recently been highlighted in nationwide, population-based cohort studies showing that all-cause mortality is significantly increased in patients with AS compared with the general population (OR = 1.60 in a Swedish cohort), and cardiovascular mortality (OR = 1.36 in a Canadian cohort) was found to be higher in patients with AS than in controls.3,21 It has been suggested that diagnostic delay and, potentially, the frequent use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), predict death and a high incidence of cardiovascular disease in those taking NSAIDs.21 Awareness of the various comorbid diseases is as important for the management of long-term debilitating illness as controlling the activity of the primary disease itself and improving QoL.22 Patients want education pertaining not only to the outcome and prognosis of the disease but also the management of situations and complications that can occur during treatment.

Self-report questionnaires are limited in the ability to obtain detailed data because they rely on patient recall. However, such surveys have the advantage of capturing the patient’s perspective on the diagnosis and treatment experience.23 This was a comprehensive analysis of real-world patient experiences based on a self-report questionnaire. There have been many advances in the treatment of AS. Nevertheless, if diagnosis and treatment decision-making are improved and disease management is considered from the patient’s perspective, better clinical outcomes can be expected.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in connection with this manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by Wonkwang University in 2020.

Authors’ contributions: JW, HS: data collection, writing and original draft. MS, KM: data collection, methodology. SJ, KS, KM: review and editing. MS, HS: supervision, writing, review and editing. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ORCID iDs: Seung-Jae Hong https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9803-529X

Hyun-Sook Kim https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9213-7140

References

- 1.Proft F, Poddubnyy D. Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis: recent insights and impact of new classification criteria. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2018; 10: 129–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohn R, Cooney M, Deodhar A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis: methodologic challenges and gaps in the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2018; 36: 263–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haroon NN, Paterson JM, Li P, et al. Patients With Ankylosing Spondylitis Have Increased Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Mortality: A Population-Based Study. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean LE, Jones GT, MacDonald AG, et al. Global prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014; 53: 650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu C, Wu B, Guo Y, et al. Correlation between diaphragmatic sagittal rotation and pulmonary dysfunction in patients with ankylosing spondylitis accompanied by kyphosis. J Int Med Res 2019; 47: 1877–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deodhar A, Mittal M, Reilly P, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis in US patients with back pain: identifying providers involved and factors associated with rheumatology referral delay. Clin Rheumatol 2016; 35: 1769–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuriya B, Tia V, Luo J, et al. Acute mental health service use is increased in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based cohort study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2020; 12: 1759720x20921710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984; 27: 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim Y, Park S, Kim HS. The effect of extra-articular manifestations on tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor treatment duration in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: nationwide data from the Korean College of Rheumatology BIOlogics (KOBIO) registry. Clin Rheumatol 2018; 37: 3275–3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvadorini G, Bandinelli F, Delle Sedie A, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: how diagnostic and therapeutic delay have changed over the last six decades. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012; 30: 561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rifbjerg-Madsen S, Christensen AW, Christensen R, et al. Pain and pain mechanisms in patients with inflammatory arthritis: A Danish nationwide cross-sectional DANBIO registry survey. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0180014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibn Yacoub Y, Amine B, Laatiris A, et al. Relationship between diagnosis delay and disease features in Moroccan patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int 2012; 32: 357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danve A, Deodhar A. Axial spondyloarthritis in the USA: diagnostic challenges and missed opportunities. Clin Rheumatol 2019; 38: 625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reilly E, Sengupta R. Back pain, ankylosing spondylitis and social media usage; a descriptive analysis of current activity. Rheumatol Int 2020; 40: 1493–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yonemoto N, Kada A, Yokoyama H, et al. Public awareness of the need to call emergency medical services following the onset of acute myocardial infarction and associated factors in Japan. J Int Med Res 2018; 46: 1747–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunkureddi P, Gibson D, Doogan S, et al. Using Self-Reported Patient Experiences to Understand Patient Burden: Learnings from Digital Patient Communities in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Adv Ther 2018; 35: 424–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webers C, Vanhoof L, Leue C, et al. Depression in ankylosing spondylitis and the role of disease-related and contextual factors: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019; 21: 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malhan S, Pay S, Ataman S, et al. The cost of care of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis patients in tertiary care rheumatology units in Turkey. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012; 30: 202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connolly D, Fitzpatrick C, O'Shea F. . Disease Activity, Occupational Participation, and Quality of Life for Individuals with and without Severe Fatigue in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Occup Ther Int 2019; 2019: 3027280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JS, Oh BL, Lee HY, et al. Comorbidity, disability, and healthcare expenditure of ankylosing spondylitis in Korea: A population-based study. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0192524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Exarchou S, Lie E, Lindström U, et al. Mortality in ankylosing spondylitis: results from a nationwide population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 1466–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younes M, Jalled A, Aydi Z, et al. Socioeconomic impact of ankylosing spondylitis in Tunisia. Joint Bone Spine 2010; 77: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeong SO, Uh ST, Park S, et al. Effects of patient satisfaction and confidence on the success of treatment of combined rheumatic disease and interstitial lung disease in a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic. Int J Rheum Dis 2018; 21: 1600–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]