Abstract

This cohort study examines disparities in patient portal use among oncology patients.

Care for oncology patients requires multidisciplinary, longitudinal coordination. Patient portals allow patients to access medical information from electronic health records (EHRs) and communicate with clinicians. This can improve treatment coordination and increase active participation in care.1 Unfortunately, disparities in patient portal use across age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status can affect quality of care, especially in oncology.1,2 To identify longitudinal disparities in access, we analyzed right-censored patient portal enrollment over an 8-year period.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective EHR-based study of a single cancer center since its adoption of an electronic patient portal, including all encounters for all patients 18 years or older to limit data acquisition bias. The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco institutional review board, and consent was waived for secondary research of a large number of patients, for whom risk of contact would pose a greater risk than the study. Self-reported demographic characteristics, encounters data, and portal use were extracted from the EHR. Enrollment in the patient portal over the study period was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Characteristics associated with enrollment were assessed with the Cox proportional hazards method. The analysis was conducted in R, version 4.0.1 (R Foundation), and statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Between June 2012 and March 2020, there were 266 917 patients with a completed visit at the cancer center. Patient characteristics are provided in the Table. The median age was 52 years (interquartile range [IQR], 36-65 years). The median time to enrollment was 262 days (IQR, 0-1327 days), and the median follow-up based on the reverse Kaplan-Meier method was 217 days (IQR, 8-1397 days).

Table. Patient Characteristics and Univariate and Multivariate Association With Patient Portal Enrollment.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Total patients, No. | 266 917 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Age subgroups, y | |||||

| 18-29 | 32 889 (12) | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 30-39 | 49 037 (18) | 1.29 (1.26-1.32) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.13-1.18) | <.001 |

| 40-49 | 40 699 (15) | 1.03 (1.01-1.05) | <.001 | 0.94 (0.92-0.96) | <.001 |

| 50-59 | 48 676 (18) | 0.94 (0.92-0.96) | <.001 | 0.86 (0.85-0.88) | <.001 |

| 60-69 | 53 108 (20) | 0.96 (0.95-0.98) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.86-0.89) | <.001 |

| 70-79 | 30 524 (11) | 0.85 (0.84-0.87) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.78-0.82) | <.001 |

| ≥80 | 11 984 (4) | 0.63 (0.61-0.65) | <.001 | 0.64 (0.62-0.66) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 111 085 (42) | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Female | 155 718 (58) | 1.08 (1.07-1.09) | <.001 | 1.07 (1.05-1.08) | <.001 |

| Other | 114 (<1) | 0.98 (0.72-1.35) | .91 | 1.07 (0.78-1.47) | .68 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 147 882 (55) | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Asian | 38 327 (14) | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | .28 | 1.13 (1.12-1.15) | <.001 |

| Black | 14 760 (6) | 0.54 (0.53-0.56) | <.001 | 0.56 (0.54-0.57) | <.001 |

| Pacific Islander | 3191 (1) | 0.80 (0.76-0.85) | <.001 | 0.84 (0.79-0.88) | <.001 |

| Native American | 1154 (<1) | 0.83 (0.77-0.90) | <.001 | 0.84 (0.78-0.91) | <.001 |

| Other | 33 315 (12) | 0.72 (0.71-0.73) | <.001 | 0.85 (0.83-0.86) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 28 288 (11) | 0.44 (0.43-0.45) | <.001 | 0.47 (0.46-0.48) | <.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Other | 240 804 (90) | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 26 113 (10) | 0.75 (0.74-0.76) | <.001 | 0.87 (0.85-0.89) | <.001 |

| Relationship status | |||||

| Partnership | 136 942 (51) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Single | 129 975 (49) | 0.74 (0.73-0.75) | <.001 | 0.76 (0.75-0.77) | <.001 |

| Language | |||||

| English | 245 013 (92) | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Other | 21 904 (8) | 0.42 (0.40-0.43) | <.001 | 0.42 (0.41-0.43) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable.

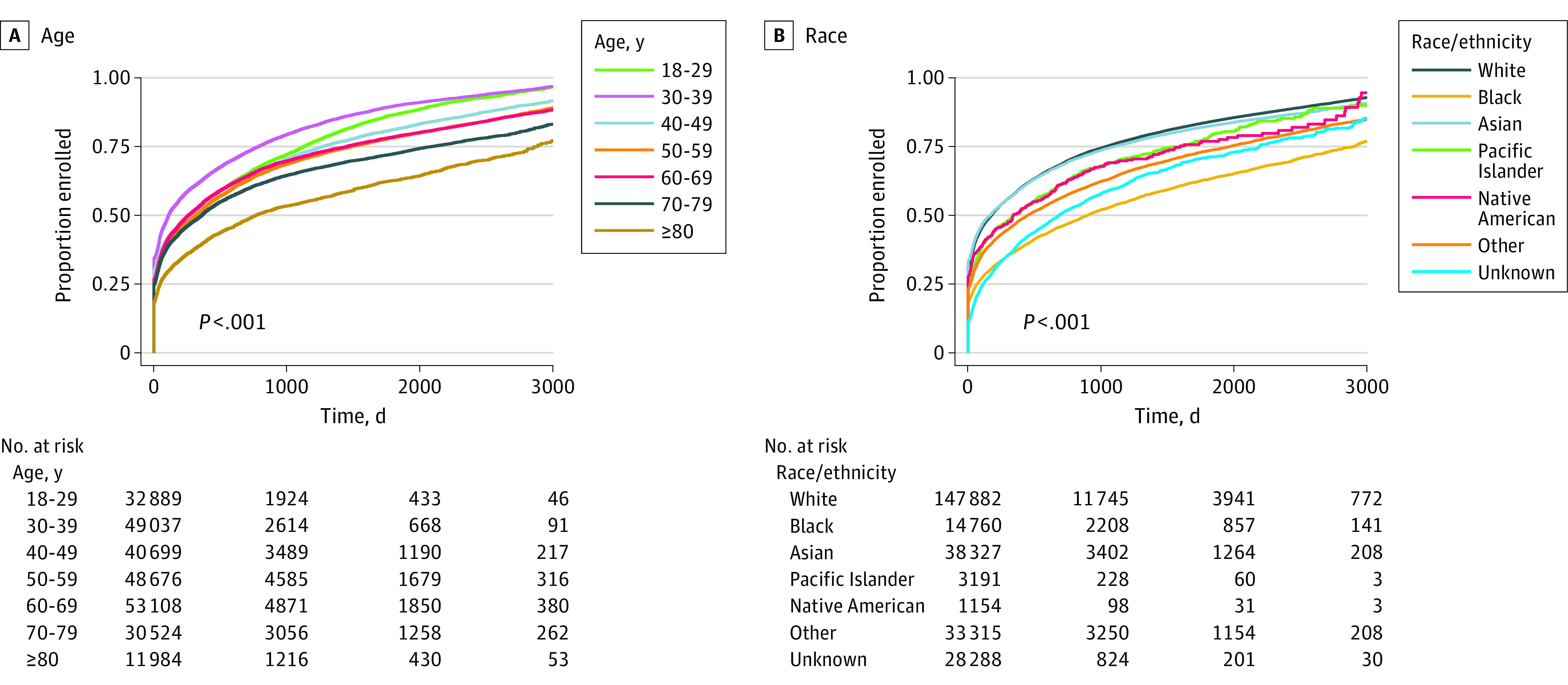

Disparities in time to enrollment were observed across sex, age, race/ethnicity, and primary language on univariate and multivariate analysis (Table). Enrollment increased in early adulthood, peaking with patients in their 40s, and subsequently decreased. Notably, patients older than 70 years had lower enrollment (Figure). Black patients were less likely to enroll at all points. Men demonstrated a small delay and decrease in enrollment compared with women. Patients whose primary reported language was not English, were Hispanic, or nonpartnered experienced lower enrollment rates.

Figure. Cumulative Enrollment Over Time Among Oncology Patients, Stratified by Age and Race.

Discussion

This study identified longitudinal disparities in patient portal enrollment, notably for patients who were older than 70 years, Black, nonpartnered, Hispanic, or had a non-English primary language. In response, our institution (University of California, San Francisco) has focused on improving the ease of enrollment, which is a substantial barrier to entry, through text messages, email, use of third-party identification instead of activation codes, and simplified proxy registration. Prior work in primary care suggests that once enrollment is overcome, disparities in use are decreased.3 Translation of the patient portal is also under way.

Oncology patients often use portals to review test results and appointment notes, communicate with their clinicians, or facilitate second opinions. Future study may investigate the association between enrollment and use, patient satisfaction, and clinical outcomes. A previous study of patients with multiple complex chronic medical conditions showed that access to patient portals was associated with more office visits, fewer emergency department visits, and fewer preventable hospital stays.4 Further, patient communication patterns via portals predict the discontinuation of therapy in patients with breast cancer,5 suggesting that portal enrollment and use may facilitate personalized care.

The limitations of this study include it being a single-institution study with a racial minority population that is overrepresented compared with the national distribution. Moreover, characteristics, such as health/technical literacy, education, and income, are not captured. The generalizability to other settings may be limited. Systemic, institutional, and clinician-level factors may be causes for the disparities identified in our study.

Ultimately, this study reveals disparities in enrollment into patient portals among oncology patients. The downstream effects of these disparities in portal enrollment may become more prominent as patients become increasingly reliant on remote communication during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly among oncology patients who are more likely to have to travel long distances for care.6 Future work is required to assess the effect and mechanisms of closing the divide.

References

- 1.Girault A, Ferrua M, Lalloué B, et al. Internet-based technologies to improve cancer care coordination: current use and attitudes among cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(4):551-557. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Chen B, et al. Predictors and intensity of online access to electronic medical records among patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(5):e307-e312. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel MS, Brown TL, Williams A, Hasnain-Wynia R, Thompson JA, Baker DW. Disparities in enrollment and use of an electronic patient portal. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1112-1116. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1728-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed ME, Huang J, Brand RJ, et al. Patients with complex chronic conditions: health care use and clinical events associated with access to a patient portal. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin Z, Harrell M, Warner JL, Chen Q, Fabbri D, Malin BA. The therapy is making me sick: how online portal communications between breast cancer patients and physicians indicate medication discontinuation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(11):1444-1451. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambroggi M, Biasini C, Del Giovane C, Fornari F, Cavanna L. Distance as a barrier to cancer diagnosis and treatment: review of the literature. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1378-1385. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]