Abstract

Use of classic psychedelics (e.g., psilocybin, ayahuasca, and lysergic acid diethylamide) is increasing, and psychedelic therapy is receiving growing attention as a novel mental health intervention. Suicidality remains a potential safety concern associated with classic psychedelics and is, concurrently, a mental health concern that psychedelic therapy may show promise in targeting. Accordingly, further understanding of the relationship between classic psychedelics and suicidality is needed. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of the relationship between classic psychedelics (both non-clinical psychedelic use and psychedelic therapy) and suicidality. We identified a total of 64 articles, including 41 articles on the association between non-clinical classic psychedelic use and suicidality and 23 articles on the effects of psychedelic therapy on suicidality. Findings on the association between lifetime classic psychedelic use and suicidality were mixed, with studies finding positive, negative, and no significant association. A small number of reports of suicide and decreased suicidality following non-clinical classic psychedelic use were identified. Several cases of suicide in early psychedelic therapy were identified; however, it was unclear whether this was due to psychedelic therapy itself. In recent psychedelic therapy clinical trials, we found no reports of increased suicidality and preliminary evidence for acute and sustained decreases in suicidality following treatment. We identify some remaining questions and provide suggestions for future research on the association between classic psychedelics and suicidality.

Keywords: Suicidality, Classic psychedelics, Psychedelic therapy, Systematic review

Classic psychedelics are a class of pharmacological agents, including psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), mescaline, and dimethyltryptamine (DMT; typically contained in the ayahuasca brew),1 that act as serotonin 5-HT2AR receptor agonists.2 These pharmacological agents have a range of effects, including altered perception, affect, and cognition.2 At higher doses, classic psychedelics drugs also produce profound alterations of consciousness, including changes in one’s sense of self3 and relationship to others,4 as well as peak or mystical-type experiences.5 Over the past two decades, a growing body of research has begun to evaluate the mental health effects, including the effects on suicidality, associated with both non-clinical classic psychedelic use (i.e., recreational and ritualistic use outside the context of a clinical intervention) and psychedelic therapy (i.e., administration of a classic psychedelic in a supportive, legally sanctioned clinical environment and often in combination with psychological preparation and integration).6,7 Accordingly, there remains a need for a synthesis of the literature on the effects of classic psychedelic use and psychedelic therapy on suicidality.

Research suggests that the lifetime prevalence rate of classic psychedelic use is increasing.8−13 Epidemiological research indicates that among United States adults the lifetime use of classic psychedelics increased from 5.8% in 2001–2002 to 9.3% in 2012–2013.10 Similarly, lifetime use of both LSD12 and psilocybin13 was found to increase from 2015 to 2018. While the cause of this increase in lifetime psychedelic use remains unclear, it may be attributable to increased psychedelic use among college students,8 efforts toward decriminalization,14 or increased research on their potential therapeutic benefits.15 The use of classic psychedelics may be associated with both positive (e.g., lower psychological distress)16 and negative (e.g., hallucinogen persisting perception disorder)17 mental health outcomes. Several studies have also suggested that there is a link between classic psychedelic use and suicidality, with some studies suggesting that classic psychedelic use is associated with decreased suicidality,16,18 some studies finding no evidence for such a relationship,19 and others reporting that classic psychedelic use is linked with increased suicidality.20 These conflicting results may be due to differences in samples (e.g., small adolescent samples vs nationally representative adult samples) or due to controlling (or failing to control) for potential confounds (e.g., use of other substances). Given these conflicting findings, alongside the increasing lifetime use of classic psychedelics8−13 and suicide rates21 within the United States, a more complete understanding of the relationship between non-clinical classic psychedelic use and suicidality is needed.

Psychedelic therapy is receiving growing attention in the field of psychiatry and has been examined as an intervention for a range of mental health presentations (for a review, see ref (22)), including major depressive disorder (MDD),23−26 distress associated with life-threatening illness,27,28 alcohol abuse,29,30 smoking cessation,31,32 and obsessive–compulsive disorder.33 To date, no clinical trials have specifically been designed to examine the effects of psychedelic therapy on suicidality, and several have excluded individuals with serious suicide risk.25 The existing evidence on this topic is indeed mixed and patchwork, as several early studies report instances of suicidality in the context of psychedelic therapy,34 and recent clinical trials have found that psychedelic therapy may be associated with decreases in suicidality among individuals with MDD.23,24,35,36 Given the importance of maximizing safety in psychedelic therapy7 and the need for innovative and rapid-acting interventions for suicidality,37−39 a further understanding of the effects of psychedelic therapy on suicidality is needed.

In sum, lifetime non-clinical classic psychedelic use is increasing, and psychedelic therapy is receiving growing attention as a novel mental health intervention. Although a growing body of research has examined the association between classic psychedelics and suicidality, this research has yielded unclear results, and importantly, there has not yet been a systematic review on the topic. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review on the association between classic psychedelics (both non-clinical psychedelic use and psychedelic therapy) and suicidality.

Results and Discussion

Study Selection and Inclusion

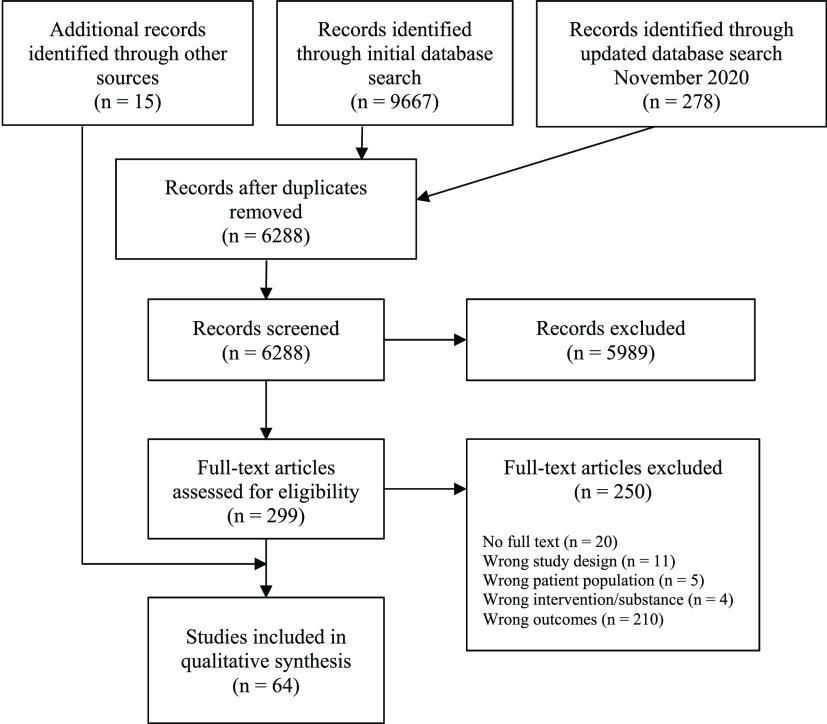

The initial database search yielded a total of 9667 potentially relevant records; 278 records were added when the search was updated in November 2020. After removing duplicates, 6288 records remained to be screened. A total of 5989 records were excluded following a review of titles and abstracts, and a further 250 were excluded following a review of their full texts. An additional 15 records were identified by manually searching reference lists of eligible studies and review articles. This resulted in a total of 64 studies eligible for inclusion in the present systematic review. Please refer to Figure 1 for an outline of the study selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Study Design and Outcomes

Included studies were categorized as either focusing on (a) the association between non-clinical classic psychedelic use (i.e., classic psychedelic use that occurred outside of a controlled and formal clinical context) and suicidality or (b) the effect of psychedelic therapy (i.e., administration of a classic psychedelic within a controlled and formal clinical context) on suicidality. For a summary of research on the association between non-clinical classic psychedelic use and suicidality, including a description of study designs, samples, classic psychedelic use, suicidality assessment method, and outcomes, see Table 1. For a summary of research on the association between psychedelic therapy and suicidality, including a description of study designs, samples, psychedelic therapy interventions, suicidality assessment method, and outcomes, see Table 2.

Table 1. Non-Clinical Classic Psychedelic Use and Suicidalitya.

| study | year | design | substance | suicidality assessment | suicidality outcome | study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal | ||||||

| Argento et al.18 | 2017 | N = 766; cohort of female sex workers; analyses conducted among individuals (n = 290) without lifetime suicidality at BL (n = 79 with psychedelic use) | lifetime use of a psychedelic (LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and MDMA) | self-reported suicidal ideation or attempt over the past 6 months (yes/no) | Lifetime use of a psychedelic was associated with reduced risk of onset of suicidality (aHR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.17–0.94). | 3 |

| Argento et al.40 | 2018 | N = 900; cohort of female sex workers; analyses conducted among individuals (n = 340) without lifetime suicidality at BL (n = 95 with lifetime psychedelic use). An overlapping (but nonidentical) sample was described in Argento et al.18 | lifetime use of a psychedelic (LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and MDMA) | self-reported suicidal ideation or attempt over the past 6 months (yes/no) | Lifetime use of a psychedelic moderated the relationship between prescription opioid use and risk of onset of suicidality (aHR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.94–7.14). | 3 |

| Davis, Averill et al.41 | 2020 | N = 51; United States veterans who completed a psychedelic clinical treatment program in Mexico | psychedelic-assisted therapy with ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT | self-reported suicidal ideation (DSI-SS [retrospective ratings of 1 month pre- and poststudy]) | Significant reduction in retrospective suicidal ideation was noted at 1 month (d = −1.9, p < 0.001). Retrospective reductions in suicidal ideation were associated with retrospective increases in psychological flexibility. | 3 |

| Zeifman, Wagner et al.42 | 2020 | study 1: N = 104; convenience samples of individuals planning to use a classic psychedelic | use of a classic psychedelic | self-reported suicidal ideation composite (SIDAS and QIDS-SI) | study 1: Significant reductions in suicidal ideation at 2 weeks (d = 0.86, p < 0.001) and 4 weeks (d = 0.98, p < 0.001) post-psychedelic use. Reductions in suicidal ideation at 2 and 4 weeks post-psychedelic use were associated with decreases in experiential avoidance (rs = 0.371, p < 0.001 and rs = 0.461, p = 0.001). | 3 |

| study 2: N = 254; convenience samples of individuals planning to use a classic psychedelic in a ceremonial context | study 1: BL and 2 and 4 weeks post-psychedelic use; study 2: BL and 4 weeks post-psychedelic use | study 2: Significant reductions in suicidal ideation were noted at 4 weeks post-psychedelic use (d = 0.52, p < 0.001). Reductions in suicidal ideation at 4 weeks post-psychedelic use were associated with decreases in experiential avoidance (rs = 0.154, p = 0.033). | ||||

| Cross-Sectional | ||||||

| Ditman et al.43 | 1967 | N = 116; individuals who reported not needing psychiatric care (n = 52), seeking outpatient care (n = 27), or receiving inpatient psychiatric care (n = 37) due to LSD use | lifetime LSD use | self-reported suicidality (“I felt like committing suicide.”) | Compared with individuals that were not receiving psychiatric care, those receiving outpatient and inpatient care due to their LSD use showed greater levels of suicidality (p < 0.01). | 3 |

| Greene and Ringwalt44 | 1996 | N = 1240 youth 12–21 years old; sample 1: n = 640 youth living in shelters; sample 2: n = 600 street-involved youth | hallucinogen use (not defined) since leaving home or in the 30 days prior to leaving home | self-reported lifetime suicide attempt (yes/no) | Use of a hallucinogen since leaving home or during the 30 days prior to leaving home was associated with an increased likelihood of a lifetime suicide attempt in sample 1 (aOR = 3.1, p < 0.001) and sample 2 (aOR = 2.9, p < 0.01). | 3 |

| Hendricks, Johnson et al.45 | 2015 | N = 191,832; population-based survey of adults in the United States. Results from this sample are also described in, Hendricks, Thorne et al.16 | lifetime use of psilocybin or other classic psychedelics (DMT, ayahuasca, LSD, peyote/San Pedro, and mescaline) | self-reported past-year suicidal ideation (yes/no), planning (yes/no), attempt (yes/no) | Lifetime use of psilocybin (and no lifetime use of any other classic psychedelic) was associated with decreased likelihood of past-year suicidal ideation (aOR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.64–0.90, p < 0.01), planning (aOR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.36–0.82, p < 0.01), and suicide attempt (aOR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.35–0.94, p < 0.05). Lifetime use of psilocybin and other classic psychedelics was associated with decreased likelihood of past-year suicidal ideation (aOR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.75–0.96, p < 0.05) and suicide attempt (aOR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.45–0.98, p < 0.05), but not past-year suicidal planning (aOR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.49–1.01, p = 0.05).b | 3 |

| Hendricks, Thorne et al.16 | 2015 | N = 191,832; population-based survey of adults in the United States | lifetime use of a classic psychedelic (DMT, ayahuasca, LSD, peyote/San Pedro, mescaline, psilocybin) | self-reported past-year suicidal ideation (yes/no), planning (yes/no), attempt (yes/no) | Lifetime use of a classic psychedelic was associated with decreased likelihood of past-year suicidal ideation (aOR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.94, p = 0.001), planning (aOR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.54–0.94, p = 0.01), and suicide attempt (aOR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.46–0.89, p = 0.008).b | 3 |

| Jimenez-Garrido et al.46 | 2020 | N = 63; long-time ayahuasca users (n = 23) and ayahuasca-naïve individuals (n = 40) | lifetime ayahuasca use | suicide risk (assessment method not described) | Among long-time ayahuasca users, 8.7% showed lifetime suicide risk. Among ayahuasca-naïve individuals, 12.5% showed lifetime suicide risk. No statistical analyses were conducted. | 3 |

| Johansen and Krebs19 | 2015 | N = 135,095; population-based survey of adults in the United States | lifetime use of a classic psychedelic (LSD, psilocybin, mescaline/peyote); past-year use of LSD | self-reported past-year suicidal ideation (yes/no), planning (yes/no), attempt (yes/no) | Lifetime use of any classic psychedelic (LSD, psilocybin, or mescaline/peyote) and past-year use of LSD were not associated with likelihood of past-year suicidal ideation, planning, or suicide attempt.b Among individuals with depression before age 18 years, lifetime use of a classic psychedelic was associated with decreased likelihood of suicidal ideation (aOR = 0.8) and plans (aOR = 0.5).b Among individuals 18–25 years old, lifetime use of a classic psychedelic was associated with decreased likelihood of past-year suicide attempt (aOR = 0.7).b | 3 |

| Kelly et al.47 | 2002 | N = 192; adolescents with a psychiatric disorder (n = 96, lifetime suicide attempt; n = 96, no lifetime suicide attempt). Individuals with lifetime suicide threat or gesture were excluded from analyses. | lifetime hallucinogen use disorder | interview-based assessment of lifetime suicide attempt (yes/no) | Controlling for the presence of bipolar disorder, hallucinogen use disorder was associated with increased likelihood of a lifetime suicide attempt (aOR = 2.53, 95% CI 1.00–6.42). | 3 |

| Kipke et al.48 | 1993 | N = 1121; youth (12–24 years old) that sought services at a primary health clinic | past-6-month use of a hallucinogen (not defined) | clinician-assessed lifetime suicide attempt (HEADSS) | Past-6-month use of a hallucinogen was associated with increased likelihood of a lifetime suicide attempt (OR = 2.44, 95% CI 1.55–3.86). | 3 |

| Lopez et al.49 | 1995 | N = 3459; Mexican students | hallucinogen use | self-report suicidal ideation (yes/no) | Lifetime use of a hallucinogen was not significantly associated with suicidal ideation (p > 0.05). | |

| Nesvåg et al.20 | 2015 | N = 135,095; population-based survey of adults in the United States; reanalysis of Johansen and Krebs19 without controlling for confounds; with a response from Johansen and Krebs50 | lifetime use of a classic psychedelic (LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, peyote) | self-reported past-year suicidal ideation (yes/no), planning (yes/no), attempt (yes/no) | Lifetime use of a classic psychedelic was associated with increased likelihood of past-year suicidal ideation (OR = 2.0, 95% CI 1.9–2.1, p < 0.001), planning (OR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.8–2.1, p < 0.001), and suicide attempt (OR = 1.8, 95% CI 1.5–2.0, p < 0.001). Johansen and Krebs respond that among individuals with lifetime psychedelic use (and without use of other illicit substances) there was not a significant relationship between lifetime psychedelic use and past-year suicidal ideation (aOR = 2.8, 95% CI 0.8–9.8, p = 0.10), planning (aOR = 3.0, 95% CI 0.4–22.9, p = 0.29), and suicide attempt (aOR = 0.8, 95% CI 0.1–6.1, p = 0.80).b | 3 |

| Rubinow and Cancro51 | 1977 | N = 201; youth (mean age = 20.8 years) | lifetime hallucinogen use (not defined) | self-reported suicidal ideation following hallucinogen use | Among participants, 8.45% of individuals reported suicide related thoughts after the immediate hallucinogen effects wore off. | 3 |

| Sexton et al.52 | 2019 | N = 356,413; representative United States sample (>12 years old) | lifetime use of a classic psychedelic (DMT, ayahuasca, mescaline, peyote/San Pedro, LSD, psilocybin) vs novel psychedelic | self-reported past-year suicidal ideation (yes/no), planning (yes/no), attempt (yes/no). | Compared with lifetime use of novel psychedelics, lifetime use of classic psychedelics (but not novel psychedelics) was associated with decreased likelihood of past-year suicidal ideation (aOR = 1.4, p = 0.018) and planning (aOR = 1.6, p = 0.029), but not suicide attempt.b | 3 |

| Sexton et al.53 | 2020 | N = 354,535; nationally representative United States sample (≥12 years old); An overlapping (but nonidentical) sample is described in Sexton et al.52 | lifetime use of a classic lysergamides (LSD), tryptamine (psilocybin, DMT, ayahuasca), and phenethylamines (peyote, San Pedro, mescaline) | self-reported past-year suicidal ideation (yes/no), planning (yes/no), attempt (yes/no) | Lifetime use of classic tryptamines was associated with decreased likelihood of past-year suicidal ideation (aOR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.72–0.87), but not with past-year suicidal planning or suicide attempt.b | 3 |

| No significant association was found between lifetime use of lysergamides or phenethylamines and likelihood of past-year suicidal ideation, planning, or suicide attempt.b | ||||||

| Shalit et al.10 | 2019 | N = 36,309; representative sample of adults in the United States | lifetime and past-year use of a hallucinogen (LSD, peyote, mescaline, psilocybin, anticholinergics, DMT, DOM, DOB, salvia divinorum, dextromethorphan, and phencyclidine); lifetime hallucinogen use disorder | self-reported lifetime suicide attempt (yes/no) | Lifetime use of a hallucinogen was associated with increased likelihood of a lifetime suicide attempt (aOR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.21–1.85).b | 3 |

| Neither hallucinogen use over the past year (aOR = 1.74, 95% CI 0.91–3.36) nor lifetime hallucinogen use disorder (aOR = 1.67, 95% CI 0.79–3.51) were associated with likelihood of a lifetime suicide attempt.b | ||||||

| Shoval et al.54 | 2006 | N = 178; Israeli adolescents with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | lifetime use of LSD | lifetime suicide attempt (medical records) | Lifetime use of LSD was associated with greater likelihood of a lifetime suicide attempt (OR = 5.7, 95% CI 1.8–17.8, p = 0.002). | 3 |

| Wong et al.55 | 2013 | N = 73,183; nationally representative sample of high school students in the United States | lifetime use of a hallucinogen (LSD, PCP, angel dust, mescaline, or mushrooms) | self-reported suicidal ideation (yes/no), planning (yes/no), attempt (0–6 or more attempts), severe suicide attempt (yes/no) | Lifetime use of a hallucinogen was associated with an increased likelihood of past-year suicide ideation (aOR = 1.8, 95% CI 1.6–2.1, p < 0.0001), planning (aOR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.7–2.2, p < 0.0001), attempt (aOR = 2.1, 95% CI 1.8–2.4, p < 0.0001), and serious attempt (aOR = 3.4, 95% CI 2.7–4.1, p < 0.0001).b | 3 |

| Yockey et al.56 | 2019 | N = 13,840; representative sample of young adults (18–25 years old) in the United States | lifetime LSD use | self-reported lifetime suicidal ideation (yes/no) | Lifetime LSD use was associated with lifetime suicidal ideation (OR = 2.46, 95% CI 2.11–2.86, p < 0.001). | 3 |

| Case Reports, Case Series, and Survey Studies | ||||||

| Baker57 | 1970 | N = 67; individuals admitted to hospital with a substance use disorder and LSD identified as one of the causes of admission | LSD use | descriptive | two suicide attempts shortly after LSD use | 4 |

| Benjamin58 | 1979 | N = 1; individual who presented to outpatient hospital with persistent panic attacks | psilocybin mushroom use | descriptive | Following psilocybin mushroom consumption, this individual “...felt suicidal several times.” | 4 |

| Benson and Holmberg59 | 1984 | N = 8206; selected (outpatients; committed inpatients; drug rehabilitation home; individuals receiving social welfare) and unselected (grade 9 students; military conscripts) samples of young individuals followed up with for 1–11 years | LSD use | report of death based on National Central Bureau of Statistics | One unnatural death occurred, due to “...jumping while under the influence of LSD”. | 4 |

| Blumenfield and Glickman60 | 1967 | N = 25; individuals brought to hospital following LSD use (n = 23, admitted to the hospital); “80 percent were diagnosed as schizophrenic or borderline schizophrenic patients” | LSD use | descriptive | Four suicide attempts occurred following LSD use (three by wrist slashing, one by aspirin overdose). | 4 |

| Bowers61 | 1977 | N = 15; individuals who experienced a prolonged psychotic reaction and received long-term follow-up | psychotomimetic drug use “probably primarily LSD” | descriptive | Two completed suicides occurred (one just prior to 1 year follow-up and one at 5 year follow-up). | 4 |

| Brodrick and Mitchell62 | 2016 | N = 1; individual with a history of depression, bipolar disorder, and traumatic childhood experiences | “...smoked cannabis that was presumably laced with lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) or phencyclidine (PCP).” | descriptive | Ten years after smoking cannabis that “...was presumed to be laced with LSD or PCP...”, the patient was admitted to an acute psychiatric unit with symptoms consistent with hallucinogen persisting perception disorder. Prior to admission, the patient had attempted suicide three times. In the months following his discharge, patient completed suicide. | 4 |

| Carbonaro et al.63 | 2016 | N = 1993; convenience sample of individuals reporting on their most psychologically difficult experience following psilocybin consumption | psilocybin mushroom use | open-ended textual responses describing acute and enduring effects of their most challenging psilocybin mushroom use | five (0.003%) cases of increased suicidality (three individuals that attempted suicide and two individuals that experienced an increase in suicidal ideation); six (0.003%) cases of complete remission of pre-existing suicidal ideation | 4 |

| Cohen64 | 1966 | review; results described in Smart and Bateman63,c | LSD use | descriptive | The authors reported two cases of accidental death which may have been suicides. In one case, a young man walked into traffic shouting “halt” after he had taken LSD. In the other, a frequent user of LSD drowned soon after he had taken LSD alone on a beach. | 4 |

| European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction66 | 2006 | survey of 14 European countries of suicides in connection with psilocybin mushroom use; data collected from sources including peer reviewed journal articles, forensic science bulletins, print and online media, personal communication with sources, surveys, and reports | psilocybin mushroom use | descriptive | The authors reported one completed suicide in which “...the presence of hallucinogenic mushrooms was detected and mentioned in the autopsy report.” A second report of completed suicide described a man who jumped out of a building window after consuming psilocybin mushrooms with alcohol. A third possible completed suicide report indicated that a man fell from a building after consuming hallucinogenic mushrooms. | 4 |

| Honyiglo et al.67 | 2019 | N = 1; 18-year old male with no known medical or psychiatric history | psilocybin mushroom use | descriptive | The individual consumed psilocybin mushrooms and died after jumping from a second floor balcony. | 4 |

| Kaasik and Kreegipuu68 | 2020 | N = 60; adults who used ayahuasca in the past year (n = 30) and matched non-ayahuasca users (n = 30) | lifetime ayahuasca use | open-ended textual responses on effects attributed to ayahuasca use | One individual reported “I got rid of suicidal thoughts, self-injuring and bouts of heavy depression.” | 4 |

| Keeler and Reifler69 | 1967 | N = 1; Undergraduate student with anxiety judged to be “mildly or moderately disturbed” | LSD use | descriptive | One individual completed suicide by jumping out of a window while under the influence of LSD. | 4 |

| Le Daré et al.70 | 2020 | N = 1; individual with no reported medical history | LSD use (based on post-mortem medical test) | descriptive | One individual found dead in his home with self-inflicted neck wounds. | 4 |

| Ludwig and Levine71 | 1965 | N = 26; inpatients with substance use disorders | use of peyote, mescaline, LSD, and psilocybin, frequently with narcotics or cannabis | descriptive | The authors described four cases of possible suicide attempts associated with psychedelic use. “[A] patient reported that a friend once tried to jump out of a window because he believed his body to be weightless. There are also reports of people walking out into the ocean but being stopped before any serious harm could occur.” | 4 |

| Müller et al.72 | 2013 | N = 1; male; details based on abstractc | psilocybin mushroom use | descriptive | One patient completed suicide through self-inflicted knife injury possibly related to previous psilocybin mushroom use. | 4 |

| Peden et al.73 | 1982 | N = 44; individuals that presented to a hospital emergency room due to the effects of psilocybin mushroom use | psilocybin mushroom use | descriptive | The authors reported that one individual “...wanted to commit suicide”. | 4 |

| Schwartz et al.74 | 1987 | N = 174; adolescents in a private, long-term drug treatment program (n = 107; LSD users) | LSD use | multiple-choice questionnaire | The authors indicated that “Twenty-one percent (n = 23) of the [adolescent] LSD users reported that they or a very close friend had been involved in a serious accident or had made a serious suicide attempt while intoxicated by LSD. Of the 23 accidents or suicide attempts, five resulted in the need for medical care at an emergency clinic or a hospital. In addition, seven... reported that they knew someone personally who had died as a result of... suicide (n = 2) during an LSD “trip”.” | 4 |

| Smart and Bateman65 | 1967 | review | LSD use | descriptive | The authors reported “one suicide attempt in 52 persons with LSD psychoses... all of these persons had taken LSD alone or with friends in unprotected settings.” | 4 |

| Ungerleider et al.75 | 1966 | N = 700; patients that presented at a psychiatric hospital and LSD was mentioned in their diagnosis or implicated as related to their visit | LSD use | descriptive; determined through medical chart review | The authors reported five suicide attempts | 4 |

| Vimmer76 | 2008 | N = 1; adult diagnosed with major depressive disorder and schizotypal personality disorder | LSD use | descriptive | The authors reported that “An adult consumed LSD many times and in one case, had a “bad trip.” Others reported that since this time... suicidal ideation increased. He had lost the meaning in his life, and the will to live. Following a rejection from a love interest... the man decided to jump off the 14th floor of his building. He ingested a mix of medications and alcohol and traveled to the 14th floor -- but passed out before jumping.” | 4 |

aHR = adjusted hazard ratio. aOR = adjusted odds ratio. BL = baseline. DMT = N,N-dimethyltryptamine. DOB = 2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine. DOM = 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine. DSI-SS = Depressive Symptom Inventory Suicidality Subscale.77 MDMA = 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine. OR = odds ratio. HEADSS = Home, Education, Activities, Drug use and abuse, Sexual behavior, Suicidality and depression.78 LSD = Lysergic acid diethylamide. SIDAS = Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale.79 QIDS-SI = Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Suicidality Item.80

Controlling for confounds.

Full-text not available.

Table 2. Psychedelic Therapy and Suicidalitya.

| study | year | design | intervention | suicidality assessment | suicidality outcome | study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials | ||||||

| Davis, Barrett et al.24 | 2020 | N = 24; individuals with major depressive disorder; wait-list controlled crossover study | psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy (two doses) | clinician-assessed suicidal ideation (CSSRS-SII) | Compared with wait list, non-significant decreases in suicidal ideation occurred over time. Post-crossover, large and significant decreases in suicidal ideation occurred (η2 = 0.44, 90% CI 0.24–0.56, p < 0.001). | 2 |

| Gasser et al.81 | 2015 | N = 12; anxiety associated with a life-threatening illness | LSD-assisted psychotherapy (two doses) | semistructured interview (12-month follow-up) | Among participants, 33% individuals reported improved symptoms including “...better sleep, no more suicidal thoughts, less depressed feelings”. | 2 |

| Zeifman et al.35 | 2019 | N = 29; individuals with treatment-resistant depression (n = 14 received active treatment); randomized placebo-controlled trial | ayahuasca (single dose) administered in a psychiatric unit | clinician-assessed suicidality (MADRS-SI [BL, 1, 2, and 7 days]) | Compared with placebo, ayahuasca was not associated with significant reductions in suicidality (p = 0.088). Moderate between-group effect sizes were observed at 1 day (d = 0.58, 95% CI −1.32–0.17), 2 days (d = 0.56, 95% CI −1.30–0.18), and 7 days (d = 0.67, 95% CI −1.42–0.08) after ayahuasca. Large within-group effect sizes were observed at 1 day (d = 1.33, 95% CI 1.25–3.18), 2 days (d = 1.42, 95% CI 1.50–3.74), and 7 days (d = 1.19, 95% CI 1.21–3.50) after ayahuasca. At 7 days after ayahuasca, there was a strong, but non-significant, association between reductions in suicidality and non-suicide-related depressive symptoms (r = 0.53, p = 0.053). | 2 |

| Open-Label Trials | ||||||

| Anderson et al.82 | 2020 | N = 18; gay-identified, cis-gender men, 50 years or older living with HIV | psilocybin-assisted group psychotherapy | clinician-assessed suicidal ideation (CSSRS-SII) | No significant decreases in suicidal ideation occurred over time, with a medium effect size (ηp2 = 0.12). At 1 day post-psilocybin, remission of suicidal ideation occurred (mean suicidal ideation = 0) across participants (mean reduction = −0.5). | 3 |

| Carhart-Harris, Bolstridge et al.23 | 2018 | N = 19; treatment-resistant depression | psilocybin (two doses) with psychological support | self-reported suicidality (QIDS-SI [BL and 1, 2, 3, 5, 18, and 36 weeks]; clinician-assessed suicidality (HAM-D-SI [BL and 1 week)] | The authors note a reduction in QIDS-SI 1 week (mean reduction = −0.90, 95% CI −0.4 to −1.4, p < 0.002) and 2 weeks (mean reduction = −0.85, 95% CI −0.4 to −1.3, p < 0.004) post-treatment; decreases at 3 weeks (mean reduction = −0.80, 95% CI −0.25 to −1.3, p = 0.01) and 5 weeks (mean reduction = −0.70, 95% CI −0.22 to −1.2, p = 0.01) post-treatment were not significant after Bonferroni correction. QIDS-SI at 18 and 36 weeks not reported. A reduction in HAM-D-SI (mean reduction = −0.58, 95% CI −0.58 to −1.3, p < 0.001) and 16 of 19 with HAMD-SI = 0 occurred at 1 week post-treatment. | 3 |

| Osório et al.83 | 2015 | N = 6; individuals with recurrent major depressive disorder. Participants were included in Zeifman, Singhal et al.36 | ayahuasca (single dose) administered in a psychiatric unit | clinician-assessed suicidality (MADRS-SI and HAM-D-SI [BL, 40, 80, 140, and 180 min, 1, 7 14, and 21 days]) | For the MADRS, the authors reported that “...the greatest score changes were observed for items related to depressed mood, feelings of guilt, suicidal ideation...”. For the HAM-D, the authors reported that “...the most significant score changes were observed for items related to apparent and expressed sadness, pessimistic thinking, suicidal ideation, and difficulty concentrating...”. Statistical tests for suicidality not reported. | 3 |

| Zeifman, Singhal et al.36 | 2020 | N = 17; recurrent major depressive disorder (n = 15 with suicidality at BL were included in analyses) | ayahuasca (single dose) administered in a psychiatric unit | clinician-assessed suicidality (MADRS-SI [BL and 40, 80, 140, and 180 min, and 1, 7, 14, and 21 days]) | Significant acute decreases in suicidality (p = 0.002) occurred, including decreases 40 minutes (Hedges’ g = 0.65, 95% CI 0.28–1.73, p < 0.05), 80 minutes (g = 0.89, 95% CI 0.53–2.14, p < 0.01), 140 minutes (g = 0.94, 95% CI 0.62–2.05, p < 0.001), and 180 minutes (g = 1.31, 95% CI 0.98–2.35, p < 0.001) after ayahuasca. Significant postacute decreases in suicidality (p < 0.001) occurred, including decreases 1 day (g = 1.62, 95% CI 1.28–2.45, p < 0.001), 7 days (g = 1.57, 95% CI 1.09–2.65, p < 0.001), 14 days (g = 1.53, 95% CI 1.21–2.52, p < 0.001), and 21 days (g = 1.75, 95% CI 1.36–2.78, p < 0.001) after ayahuasca. Among the two individuals with no suicidality at BL, one had a score of MADRS-SI = 1 at 1 day post-ayahuasca and returned to MADRS-SI = 0 at all other time points. The other individual showed no elevation in suicidality. Acute (40 min) and postacute (21 days) reductions in suicidality were associated with reductions in nonsuicide related depressive symptoms (r = 0.69, p = 0.005 and r = 0.52, p = 0.049). | 3 |

| Case-Reports, Case Series, and Survey Studies | ||||||

| Baker34 | 1964 | N = 150; patients with “non-functional psychiatric disorders” | LSD therapy (1–10 sessions) | descriptive | One completed suicide and one sudden death of unknown cause (both weeks after LSD administration) occurred. The authors reported that “suicidal... risk has not been increased... This experience is not out of line with ordinary suicide risk in a comparable group of patients not subjected to this form of treatment.” The authors reported at least nine serious suicide attempts within this patient group prior to LSD therapy | 4 |

| Chandler and Hartman84 | 1960 | N = 110; psychiatric patients | LSD therapy (1–26 doses per patient; mean = 6.2) | descriptive | One suicide occurred following LSD therapy in a previously suicidal patient | 4 |

| Cohen85 | 1960 | N = 44; survey of clinicians providing LSD and mescaline therapy to “almost five thousand individuals... on more than 25,000 occasions” | LSD and mescaline therapy (1–80 doses) | descriptive | The authors described post-LSD therapy suicidal behavior not reported elsewhere in the present review: one completed suicide, two suicide attempts, and one instance of wrist slashing with a razor blade (not identified as a suicide attempt). The authors reported that “In only a very few instances a direct connection between the LSD experience and the movement toward self-destruction could be discerned...” and that “...all suicidal acts have been in disturbed patients rather than normal subjects.” Among individuals that received psychedelic therapy, estimated rates were attempted suicide = 1.2/1000 and completed suicide = 0.4/1000, and in “experimental subjects”, the rate was 0/1000 for both attempted and completed suicides. | 4 |

| Cohen and Ditman86 | 1963 | N = 5; individuals with a range of clinical presentations | LSD therapy (8 doses) | descriptive | One female was included with challenging and “chaotic” early life experiences; prior to LSD therapy, she had made a suicide attempt. At 2 years following LSD therapy, she was “...obsessed about going crazy or killing herself...”. She attempted suicide with barbiturates some time after the LSD therapy. | 4 |

| Denson87 | 1969 | N = 237; individuals with a range of clinical presentations (primarily inpatients) | LSD therapy (1–11 doses; mean doses = 1.74); 411 total number of treatment sessions | descriptive | The authors reported two completed suicides and one suicide attempt in individuals that had received LSD therapy (1 and 5 years after LSD therapy). The authors described one suicide attempt (2 days after LSD therapy) and one instance of “...short-lived paranoid state with suicidal impulses...” immediately following LSD therapy and 3 months later. They also indicated that four individuals were “...considered to be in danger of injuring himself or committing suicide...”. | 4 |

| Eisner and Cohen88 | 1958 | N = 2; review; describes suicide-related outcomes not reported elsewhere | experimental administration of LSD | descriptive | On the basis of personal communication, the authors reported two completed suicides. They also reported that “Personal contact with therapists using LSD-25 have turned up other cases of suicidal preoccupation and of actual suicide...” and “We are inclined to believe... that the possibility of suicide may be a real hazard, as it is in the treatment of any serious mental illness. From our experience... this danger appears to be restricted to the higher dosage level–those above 75 gamma–and an unfamiliarity with the drug.” | 4 |

| Fink et al.89 | 1966 | N = 65; treatment-resistant patients with psychosis receiving in-patient care | LSD therapy (1–15 doses) | descriptive | One suicide attempt occurred 3 days after LSD therapy. The author noted that 2% of patients who received repeated LSD therapy had “prolonged adverse reactions” and that the risks of these “prolonged psychoses” associated with LSD abuse, including “suicidal preoccupations”, are greater in “...subjects with emotional lability and psychopathic features rather than in those with more classical forms of schizophrenia...”. | 4 |

| Geert-Jörgensen et al.90 | 1964 | N = 157; individuals with a range of psychiatric disorders | LSD therapy (5–58 doses) | descriptive | One completed suicide (6 months after treatment) was reported, unrelated to LSD therapy. Four suicide attempts (one deemed serious and three deemed not serious) in the days after LSD therapy. The authors reported that these suicide attempts “...did not occur at times when the patients had been in states attributable to the LSD-after-effects repercussions...”. | 4 |

| Knudsen91 | 1964 | N = 1; female patient; results described in Smart and Bateman65,b | LSD therapy (5 doses) | descriptive | suicidal ideation and one suicide attempt | 4 |

| Kristensen92 | 1962 | N = 23; individuals with a range of clinical presentations | LSD therapy (large doses of LSD) | descriptive | A male patient with “severe character neurosis” completed suicide (1 h after LSD administration). | 4 |

| Malleson93 | 1971 | N = 4470 (n = 4300, patients in the United Kingdom administered LSD 49,000 times in a clinical context; n = 170, experimental subjects administered LSD 450 times); survey of doctors (N = 73) administered LSD to humans | LSD administered in a clinical or experimental research context | descriptive | Among those administered LSD in a clinical context, there were three completed suicides that “...appeared to have a temporal relationship to LSD”. Nine cases of serious suicide attempt also occurred, as did eleven potential suicide attempts where “...the data are insufficient to categorize them.” Suicide rate of 0.0007%. No completed or attempted suicides reported among experimental subjects. | 4 |

| Martin94 | 1964 | N = 1; adult with delusions of persecution, hallucinations, ideas of reference, occupational impairment and “suicidal feelings” | LSD therapy (12 doses) | descriptive | The authors reported that the patient gained “...insight into the meaning of his symptoms, leading to a resolution of his conflicts. One year later his stability had not relapsed.” | 4 |

| Sandison and Whitelaw95 | 1957 | N = 94; individuals with varying psychiatric disorders | LSD therapy | descriptive | One suicide attempt by strangulation and three individuals who wished to suicide by drowning occurred during the acute phase of the LSD experience. “Patients in this condition can usually be persuaded to take pentobarbitone, after which the suicidal tendencies subside and are not necessarily present between treatments.” The authors reported that “In our experience, marked suicidal urges have particularly occurred during the treatment of anxiety neurosis, and are not necessarily confined to patients who had depressive or suicidal ideas before treatment was commenced... among the risks of treatment, the emphasis should be shifted to the possibility of suicide.” | 4 |

| Savage96 | 1957 | N = 6; inpatients | LSD therapy (weekly) | descriptive | One female inpatient with schizophrenia and chronic somatic illusions of being dead completed suicide (by throwing herself under a train) while on a visit home. | 4 |

| Savage et al.97 | 1964 | N = 113; individuals with a range of clinical presentations | LSD or mescaline therapy (1 dose) | descriptive | One suicide attempt occurred 2 months after LSD therapy (individual with history of depression, suicidal attempts, and hospitalization). | 4 |

| Van Ree98 | 1969 | N = 1; severely suicidal patient | LSD therapy | descriptive | Clinical improvements were reported in a “patient with suicidal tendencies which had been present in a very severe form for many years”. | 4 |

BL = baseline. CSSRS-SII = Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale-Suicidal Ideation Intensity.99 HAM-D-SI = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-Suicidality Item.100 LSD = Lysergic acid diethylamide. MADRS-SI = Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale-Suicidality Item.101 QIDS-SI = Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Suicidality Item.80

Full-text not available.

Quality Appraisal

Three studies utilized a randomized controlled trial design. All other study designs were open-label trials, longitudinal cohorts, cross-sectional surveys, and case reports or case series, with the majority (36/64) being case reports or case series. Accordingly, the most commonly occurring quality rating was a level 4. See Table 1 (non-clinical classic psychedelic use) and Table 2 (psychedelic therapy) for the quality ratings of each study. See Table 3 for an overview of all included studies’ designs and quality appraisal ratings.

Table 3. Study Design and Quality Appraisal.

| quality

appraisal |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| study design | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | number of studies |

| case report/series | 36 | 36 | ||||

| cross-sectional | 17 | 17 | ||||

| longitudinal | 4 | 4 | ||||

| open-label trial | 4 | 4 | ||||

| randomized controlled trial | 3 | 3 | ||||

| total | 3 | 25 | 36 | 64 | ||

The studies included in our review reflect the highly variable nature of evidence in this field, both in study design and in year of publication, and thus also in scientific standards and terminology used. The study methodologies used tend to approach the effects of psychedelics on suicidality from either a detrimental or beneficial therapeutic lens, a methodological bias that remains an unresolved issue in the field.102 Below, evidence from non-clinical classic psychedelic use and its association with suicidality is explored first, followed by a review of results from both early and late psychedelic therapy research. We conclude with an overview of the significance of these findings and their implications for future psychedelic research.

Non-Clinical Classic Psychedelic Use and Suicidality

Several studies included in this review focused on classic psychedelic use outside the context of clinical studies. These studies describe the effects of recreational and ritualistic non-clinically sanctioned psychedelic use on suicidality across several population sample types, and they include data from as early as 1965. The five longitudinal cohort studies published were all completed within the past 5 years. Two of these studies provide support for a protective effect of classic psychedelic use on suicidality.18,40 Three studies showed support for classic psychedelic use (within contexts including ceremonial settings and within an observational clinical context) being associated with subsequent reductions in suicidal ideation.41,42 Both studies also found that reductions in suicidal ideation were associated with decreases in experiential avoidance, providing preliminary support for its potential role as a mechanism underlying the effects of classic psychedelic use on suicidality. As these studies are prospective, they lack the retrospective design bias of the studies below and point to the possibility that classic psychedelics may have a protective effect and may lead to reductions in suicidality in these specific populations.

Of the 17 cross-sectional studies included in this review, 10 demonstrated an association between classic psychedelic use and increased suicidal ideation and/or attempts, while 8 studies showed either a potential association between classic psychedelic use and either reduced suicidality or no clear association. Of these studies, the largest and most compelling are from national survey data from the United States. Several cross-sectional studies16,19,45,52,53 suggest that classic psychedelic use is associated with lower levels of suicidality, while two studies10,20 suggest that psychedelic use is associated with higher levels of suicidality. Interestingly, the analysis of Nesvag et al.,20 which suggested that psychedelic use is associated with higher levels of suicidality, used the same data as Johansen and Krebs,19 who found that psychedelic use was associated with lower levels of suicidality. In response to the article by Nesvag et al.,20 Krebs and Johansen50 rebutted that there could be no clear conclusion drawn from the data and that there was no evidence to suggest an increased risk of suicidality in psychedelic users when accounting for multiple confounders (i.e., age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, education, marriage status, risky behaviors, presence of a depressive episode before age 18, and use of other illicit drugs), for which Nesvag et al.20 did not account. This is important, as many psychiatric covariates can significantly affect levels of suicidality in and of themselves. Similarly, Yockey et al.56 found an association between LSD use and past suicidal ideation in American young adults but failed to control for psychiatric confounds. Wong et al.55 also corroborated the finding of a positive association between psychedelic use and suicidality, although this analysis was done exclusively in high school students. Importantly, causality cannot be inferred from these results due to the cross-sectional study designs. Additionally, few studies have included confounders of personality disorders (e.g., borderline personality disorder), another known major contributor to substance use103 and suicidality.104

Of the 20 case reports, case series, and surveys (including convenience samples, general surveys, patient interviews, and a survey of adolescents in a drug treatment program) included in our systematic review, 13 suggest a possible association between psychedelic use and increased suicidality, while 5 do not suggest any clear association (see refs (59), (65), (66), (73), and (75)). Several studies found evidence for cases of self-reported remission of suicidality following classic psychedelic use.63,68 In all the studies included in our review, we identified 11 deaths presumed to be completed suicides that can be fairly confidently linked to classic psychedelic use in a non-clinical context (four jumping from a height [of which one of these individuals was also intoxicated on alcohol], one walking into traffic [unclear intent], one drowning [alone on the beach with unclear intent], two self-stabbing with a sharp object or knife, and three with unclear methods). This supports the notion that noncontrolled environments where individuals are by themselves and have access to means for suicide, such as heights with no barriers and objects that can lead to hanging or self-stabbing, are likely unsafe contexts for psychedelic use, especially among individuals presenting with prior suicide risk. There is much evidence suggesting that restricting access to lethal means is a key method for suicide prevention in general,105 and it stands to reason that for those using psychedelic substances in non-clinical settings, the pre-emptive restriction of lethal means could help reduce the risk of suicide.

It is important to note that it was often unclear if the substance used was, in fact, a classic psychedelic, and that instances of suicide associated with psychedelic use were rare. Accordingly, while classic psychedelic use is not without potential risks, the results of the present systematic review are in line with past research suggesting that classic psychedelics show a fairly strong safety profile (e.g., low risk of abuse or harm).7,106−108 Additionally, this relative risk needs to be considered in comparison with the greater risk associated with other substances that have been linked with suicide and suicide attempts, including recreational (e.g., acute alcohol use is strongly associated with increased likelihood of attempting suicide, OR = 6.97, 95% CI = 4.77–10.17)109 and pharmaceutical drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines110 and potentially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).111,112 It is also likely the case there is a publication bias toward negative outcomes in this portion of the literature, as positive outcomes of recreational psychedelic use are rarely brought to medical attention and are therefore unlikely to be published.

Overall, research on the effects of non-clinical psychedelic use on suicidality is mixed and hampered by reliance on self-reported data. This is in addition to the fact that suicidality is an inherently difficult area of study given the rarity of actual suicide completions. Preregistered analyses, using large prospective national registries with extensive information on substance use history and psychiatric and demographic factors, will be important for shedding light on the true nature of the effects of psychedelic use on suicidality outside clinical settings.

Psychedelic Therapy and Suicidality

Early Psychedelic Therapy Research and Suicidality

Results from our review tabulate 16 early studies that describe the effects of psychedelic therapy (specifically classic psychedelics) on suicidality. These are limited to case reports, case series, and surveys, which echo the above notion of the limited evidence available in this field up until the past several years. These studies were not prospectively designed to investigate the effects of psychedelics on suicidality and represent retrospective reports. In these 16 studies, there are several large case series completed on patients with a mixture of psychiatric diagnoses, many with antiquated diagnoses no longer in use. Nonetheless, the majority of these studies do not suggest an increased suicidality risk with psychedelic therapy above baseline, especially given the high inherent risk of suicide in these subjects diagnosed with chronic and severe mental illness.34,84,87,89,90,95,97 In addition to these case series, several individual case reports attempt to shed light on the relationship between psychedelic therapy and suicidality. Two studies suggest a potential causative effect of psychedelics on increased suicidality in patients treated with psychedelic therapy.92,96 However, several case reports specifically describe clear improvement in chronic suicidality attributed to psychedelic therapy.94,98 In these studies, we identified a total of 6 deaths presumed to be completed suicides that can be reasonably linked temporally to early psychedelic therapy (1 after LSD treatment in a previously suicidal patient; 1 after LSD treatment in a patient with character neurosis; 3 with a temporal relation to psychedelic administration; and 1 in an inpatient with schizophrenia receiving weekly LSD treatment who completed suicide on a day pass). Overall, while limited in number and quality of evidence, these reports do not suggest a strong association between psychedelic therapy and suicidality from this first wave of early research.

Analysis of the rate of completed suicide in these study populations can crudely demonstrate the relative frequency of completed suicide in comparison to known modern suicide rates. The data from these early psychedelic therapy studies come from two nonsystematic survey studies in which authors attempted to survey, presumably by mail, local clinicians who were providing psychedelic therapy. In a UK sample, Malleson derived a suicide rate of 0.7/1000 patients out of 4300 total patients described by respondents.93 In a US survey, Cohen describes a suicide rate of 0/1000 in experimental subjects and 0.4/1000 in patients undergoing therapy out of a total of approximately 5000 subjects. It is important to note that the patients in these studies were often treated on multiple occasions potentially over several years and included individuals with psychotic and other severe mental illnesses. Also, psychedelic treatment could not always be causally linked to the completed suicide in these studies. These suicide rates are higher than the current global suicide rate of 11.4/100,000, yet they are far lower than the suicide rate of modern psychiatric patients around the time of hospital discharge, 484/100,000, which likely represents a more appropriate comparator sample.113 In sum, while these early studies lack rigorous methodology, they suggest that there is limited evidence to associate psychedelic therapy with increased risk of suicidality, and they point toward improvement in suicidality in select cases and the overall relative safety with regards to suicidality of administering psychedelics in controlled settings, even in presumed high-risk patient populations.

Modern Psychedelic Therapy Research and Suicidality

To date, although no clinical trials have been designed to evaluate the effect of psychedelic therapy on suicidality, several trials have reported on the effect of psychedelic therapy on suicidality. Importantly, given that these trials have not specifically recruited individuals high in suicidality and have included individuals with no suicidality at baseline, these studies may be confounded by potential floor effects. We identified two randomized controlled trials and three open-label trials that examined the effect of psychedelic therapy on suicidality. In a small (N = 25) wait-list-controlled crossover trial, individuals with MDD were assigned to either psilocybin therapy or wait-list control followed by psilocybin therapy. Before crossover, reductions in suicidality in the psilocybin condition were not significantly greater than those in the wait list condition.24 Post-crossover, there was a significant decrease in suicidality with a large effect size. These results do not provide conclusive evidence for psilocybin therapy causing reductions in suicidality, as the post-crossover results may be due to the passage of time itself (e.g., regression to the mean). Alternatively, the non-significant effect before crossover may be attributable to a lack of power to detect significant effects relative to the control condition. In an open-label trial, following psilocybin therapy, individuals with treatment-resistant depression showed significant reductions in suicidality at 1 and 2 weeks post-treatment.23 Of note, individuals also showed decreases in suicidality at 3 and 5 weeks post-treatment; however, these reductions were no longer significant after Bonferroni correction. In an open-label trial, individuals with HIV-related demoralization received group therapy and a single dose of psilocybin.82 Results showed remission from suicidality across all participants at 1 day post-psilocybin administration and a non-significant reduction in suicidality at post-treatment (3 weeks post-psilocybin), with a medium-large effect size.82 Within a small (N = 29) randomized controlled trial, individuals with treatment-resistant depression received either ayahuasca or placebo. Compared with placebo, ayahuasca was not associated with a significant reduction in suicidality but was associated with a medium between-group effect size.35 Furthermore, ayahuasca was associated with a large within-group effect size for decreases in suicidality at 1, 2, and 7 days post-ayahuasca. Similarly, in an open-label study, following a single administration of ayahuasca, individuals with recurrent MDD showed rapid (i.e., within 40 min of administration) and significant decreases in suicidality, as well as large and sustained reductions in suicidality 1, 7, 14, and 21 days later.36 Both of these studies35,36 found a strong relationship between reductions in suicidality and non-suicidal depressive symptoms, suggesting that there may be overlapping mechanisms between the effects of psychedelic therapy on global depressive symptoms and suicidality.

In sum, the above results provide preliminary evidence that psychedelic therapy may be associated with acute and sustained reductions in suicidality. However, the efficacy of psychedelic therapy compared with wait-list- or placebo-controlled conditions has not yet been established. Additional important limitations include the use of small sample sizes, studies not specifically recruiting individuals high in suicidality (and frequently excluding individuals high in suicide risk), relatively short duration of suicidality assessment (i.e., no assessments more than 6 months post-treatment), and frequent measurement of suicidality using a single item from a depression severity measure. Additionally, to date, only one study has examined the acute effect of psychedelic therapy on suicidality. Therefore, while there may be preliminary evidence for the potentially rapid-acting effect of psychedelic therapy on suicidality, there remains a need for adequately powered randomized controlled trials that are designed to examine the effect of psychedelic therapy on suicidality.

Importantly, within modern psychedelic therapy clinical trials, no adverse suicide-related events or significant escalations of suicidality due to the administration of a psychedelic have been reported, suggesting that modern psychedelic therapy shows a strong safety profile. Although we identified several instances of suicide-related adverse events that occurred in early psychedelic therapy trials, the positive safety outcomes associated with modern psychedelic therapy research may be attributable to several factors including more rigorous screening before participants are enrolled in trials (e.g., serious suicide risk was an exclusion in some trials, and the presence of bipolar and psychotic-related disorders have consistently been exclusion criteria)7 and closer attention to and understanding of the importance of the therapeutic frame within psychedelic therapy. As research continues to relax exclusion criteria (e.g., for a recent trial specifically recruiting individuals with bipolar disorder II; see clinicaltrials.gov NCT 04433845) and potentially aim to target individuals high in suicide-risk, even greater attention will need to be placed on the importance of the therapeutic intervention and the environment in which the psychedelic is administered. Accordingly, above and beyond the traditional psychedelic therapy safety guidelines,7 we provide several recommendations for minimizing risks when providing psychedelic therapy to individuals high in suicide risk. First, we suggest that integrating psychedelic therapies with evidence-based interventions for suicidality (e.g., dialectical behavior therapy,114 cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention)115 may help to maximize safety and treatment outcomes (for further discussion, see ref (116)). At a minimum, we advise that a suicide risk management protocol117 should be included when providing psychedelic therapy to individuals high in suicide risk. Second, following psychedelic therapy sessions, participants should remain in a controlled environment until potential suicide risks are minimized or assessment indicates that there are no significant elevations in suicidality. Additionally, safety monitoring should occur between psychedelic therapy sessions. When feasible, providing psychedelic therapy within an inpatient or residential treatment context may also help to ensure that the intervention is tolerated and safe. Third, to minimize potential risks, initial research may examine the safety and efficacy of psychedelic therapy among individuals with elevated levels of suicidality (e.g., clinically significant suicidal ideation without current intent), while excluding individuals that are imminently suicidal or those with a recent (i.e., within the past 2 months) life-threatening suicide attempt. Should the safety-related data from such research continue to suggest that psychedelic therapy is safe, tolerable, and potentially efficacious within these populations, psychedelic therapy could then be examined among individuals with even more severe presentations.

Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

This is the first systematic review to explore the effects of classic psychedelics on suicidality in both clinical and non-clinical settings. The results suggest that psychedelic therapy may be beneficial in reducing suicidality in certain diagnosed, clinical psychiatric populations and that classic psychedelic use may buffer against, and may be associated with reductions in, suicidality. However, within unsafe and un-monitored settings, psychedelic use can on rare occasions also lead to fatal consequences including suicide. These conclusions are preliminary given the highly limited nature of the source literature; this review includes only three small prospective, randomized trials and only four additional prospective, small open-label trials. The majority of the studies included are small case reports or case series with mostly retrospective data. Our study is limited by the publication record on this topic itself, as there was a significant paucity of published reports on psychedelics in general between the initial wave of studies in the 1960s and more recent trials. Also, the vast majority of the studies included do not list suicidality as a primary outcome, and many do not use standardized scales to measure suicidality in their reports. While there is support for using single-items from depression severity measures to assess suicidality,118,119 future research would benefit from including measures specifically designed to assess suicidality (e.g., Scale for Suicide Ideation),120 implicit measures of suicidality (e.g., Death/Suicide Implicit Association Test),121 and clinician-administered measures that assess both suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors (e.g., Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scales).99 Finally, there remains a very limited understanding of the putative mechanisms of action through which classic psychedelics may affect suicidality, as explored below.

In reviewing the theoretical mechanisms of action of psychedelics on suicidality, the potential for increased suicidality may be attributable to acutely impaired executive functioning122 or challenging emotional experiences,63 especially when used without paying appropriate attention to context (e.g., within non-clinical contexts).123 In terms of reduced suicidality potentially associated with classic psychedelics, several studies suggest that this may be attributable to decreases in experiential avoidance and mechanisms that overlap with decreases in depression severity. However, this research remains preliminary. Additional research that examines the experiential (e.g., insight124 and emotional breakthrough),125 psychological (e.g., reduced distress,16,35 emotional avoidance,41,42 and revised maladaptive beliefs),126 immunomodulatory,127 and neurobiological (e.g., potential neuroplastic effects,128,129 acute increases in entropy,130 and changes in functional connectivity)131 effects of psychedelics may shed light on how classic psychedelics affect suicidality. Such research may also provide guidance on how psychedelic therapy may be used to help those struggling with this potentially life-threatening presentation. Future large, prospective cohort studies may elucidate the effects of non-clinical classic psychedelic use on suicidality in the general public, while large, prospective clinical trials and meta-analyses of existing data sets may help to confirm the potential therapeutic role of psychedelic therapy in treating suicidality in psychiatric patients.

Methods

This systematic review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.132 The protocol for this study was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020158443).

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and PubMed databases on March 28, 2020 from their respective inception dates, without time or language restrictions, using the following terms: (psychedelic* OR hallucinogen* OR psilocybin OR ayahuasca OR DMT OR dimethyltryptamine OR mescaline OR peyote OR LSD OR lysergic acid diethylamide) AND (mood* OR distress* OR depress* OR suicid* OR PTSD* OR post-trauma* OR post trauma* OR posttrauma* OR anxiety* OR schizophren* OR bipolar). All studies involving the association between, or effect of, classical psychedelics (non-clinical classic psychedelic use and psychedelic therapy) and suicidality outcomes were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. Studies were excluded if they focused on psychedelic microdosing or examined the effects of psychoactive compounds not considered classic psychedelics (e.g., ketamine, benzodiazepines, cannabis, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA]). There were no exclusion criteria related to gender, age, psychiatric diagnoses, or year of publication. The search was repeated on November 5, 2020 to identify any articles published after the original search was performed. Additionally, we searched the reference lists of eligible studies and review articles to identify further relevant studies.

Data Extraction

After duplicates were removed, two reviewers (N.S. and R.J.Z.) independently screened all titles and abstracts based on the identified inclusion and exclusion criteria to remove irrelevant records. They then independently screened all remaining full-text articles according to the same eligibility criteria. Consensus on all items was reached through discussion over any disagreements, with a third reviewer (C.R.W.) consulted when necessary. Two authors (R.J.Z. and L.B.) subsequently extracted the following data from the included studies: study authors, publication year, study design, study duration, inclusion/exclusion criteria, participant demographics, baseline characteristics, sample size and descriptions of groups, details on classic psychedelic use and interventions, suicidality outcome measures and items used, and suicidality outcomes. In cases where suicidality-related data were reviewed in a manuscript, but the primary source of the report was not accessible, available data were extracted from the secondary source.

Quality Appraisal

We assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (OCEBM) Levels of Evidence.133 This approach is designed to enable a critical appraisal of papers using any methodology, in contrast to tools that are specifically designed to evaluate only the quality of a given methodology (e.g., qualitative papers or randomized controlled trials). Scores are in the range of levels 1–5, with 1 corresponding with the highest quality of evidence and 5 with the lowest. This assessment was performed by one author (N.S.) and verified by a second (R.J.Z.). Study quality was evaluated based on the methodological quality of the suicidality outcomes reported in each study.

Author Present Address

C.R.W.: Temerty Centre for Therapeutic Brain Intervention, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Author Contributions

R.J.Z., N.S., and C.R.W. contributed to study design and conception. R.J.Z., N.S., and L.B. conducted the systematic search of the literature and study selection. N.S. and R.J.Z. conducted the quality appraisal. All authors read, critically revised, and approved the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- dos Santos R. G.; Hallak J. E. C. (2019) Ayahuasca, an Ancient Substance with Traditional and Contemporary Use in Neuropsychiatry and Neuroscience. Epilepsy Behav 106300. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols D. E. (2016) Psychedelics. Pharmacol. Rev. 68 (2), 264–355. 10.1124/pr.115.011478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nour M. M.; Carhart-Harris R. L. (2017) Psychedelics and the Science of Self-experience. Br. J. Psychiatry 210 (3), 177–179. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.194738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris R. L.; Erritzoe D.; Haijen E.; Kaelen M.; Watts R. (2018) Psychedelics and Connectedness. Psychopharmacology 235 (2), 547–550. 10.1007/s00213-017-4701-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James E.; Robertshaw T. L.; Hoskins M.; Sessa B. (2020) Psilocybin Occasioned Mystical-Type Experiences. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 35 (5), e2742. 10.1002/hup.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Romeu A.; Richards W. A. (2018) Current Perspectives on Psychedelic Therapy: Use of Serotonergic Hallucinogens in Clinical Interventions. Int. Rev. of Psychiatry 30 (4), 291–316. 10.1080/09540261.2018.1486289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. W.; Richards W. A.; Griffiths R. R. (2008) Human Hallucinogen Research: Guidelines for Safety. J. Psychopharmacol. 22 (6), 603–620. 10.1177/0269881108093587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L. S.; Gold J. A. (2020) Hallucinogen Use in College Students: Current Trends and Consequences of Use. Curr. Psychopharmacol. 9 (2), 115–127. 10.2174/2211556009666200311140404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar J. J.; Le A. (2018) Trends in DMT and Other Tryptamine Use Among Young Adults in the United States. Am. J. Addict. 27 (7), 578–585. 10.1111/ajad.12803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalit N.; Rehm J.; Lev-Ran S. (2019) Epidemiology of Hallucinogen Use in the US Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. Addict. Behav. 89, 35–43. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) . (2019) Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, SAMHSA, Rockville, MD. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf.

- Yockey R. A.; Vidourek R. A.; King K. A. (2020) Trends in LSD Use among US Adults: 2015–2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 212, 108071. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yockey A., and King K. (2021) Use of Psilocybin (“Mushrooms”) Among US Adults: 2015–2018. J. Psychedelic Stud. 10.1556/2054.2020.00159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noorani T. (2019) Making Psychedelics into Medicines: The Politics and Paradoxes of Medicalization. J. Psychedelic Stud. 4 (1), 34–39. 10.1556/2054.2019.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt D.; Erritzoe D.; Carhart-Harris R. (2020) Psychedelic Psychiatry’s Brave New World. Cell 181 (1), 24–28. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks P. S.; Thorne C. B.; Clark C. B.; Coombs D. W.; Johnson M. W. (2015) Classic Psychedelic Use is Associated with Reduced Psychological Distress and Suicidality in the United States Adult Population. J. Psychopharmacol. 29 (3), 280–288. 10.1177/0269881114565653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinotti G.; Santacroce R.; Pettorruso M.; Montemitro C.; Spano M. C.; Lorusso M.; di Giannantonio M.; Lerner A. G. (2018) Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder: Etiology, Clinical Features, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Brain Sci. 8 (3), 47. 10.3390/brainsci8030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argento E.; Strathdee S. A.; Tupper K.; Braschel M.; Wood E.; Shannon K. (2017) Does Psychedelic Drug Use Reduce Risk of Suicidality? Evidence from a Longitudinal Community-Based Cohort of Marginalised Women in a Canadian Setting. BMJ. Open 7 (9), e016025. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen P. Ø.; Krebs T. S. (2015) Psychedelics Not Linked to Mental Health Problems or Suicidal Behavior: A Population Study. J. Psychopharmacol. 29 (3), 270–279. 10.1177/0269881114568039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvåg R.; Bramness J. G.; Ystrom E. (2015) The Link Between Use of Psychedelic Drugs and Mental Health Problems. J. Psychopharmacol. 29 (9), 1035–1040. 10.1177/0269881115596156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H., Curtin S. C., and Warner M. (2020) Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief No. 362, National Center for Health Statistics, DHHS, Hyattsville, MD. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db362.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K. A. A., Carhart-Harris R., Nutt D. J., and Erritzoe D. (2020) Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: A systematic review of modern-era clinical studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 143, 10.1111/acps.13249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart-Harris R. L.; Bolstridge M.; Day C. M. J.; Rucker J.; Watts R.; Erritzoe D. E.; Kaelen M.; Giribaldi B.; Bloomfield M.; Pilling S.; Rickard J. A.; Forbes B.; Feilding A.; Taylor D.; Curran H. V.; Nutt D. J. (2018) Psilocybin with Psychological Support for Treatment-resistant Depression: Six-month Follow-Up. Psychopharmacology 235 (2), 399–408. 10.1007/s00213-017-4771-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. K., Barrett F. S., May D. G., Cosimano M. P., Sepeda N. D., Johnson M. W., Finan P. H., and Griffiths R. R. (2020) Effects of Psilocybin-assisted Therapy on Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palhano-Fontes F.; Barreto D.; Onias H.; Andrade K. C.; Novaes M. M.; Pessoa J. A.; Mota-Rolim S. A.; Osório F. L.; Sanches R.; dos Santos R. G.; et al. (2019) Rapid Antidepressant Effects of the Psychedelic Ayahuasca in Treatment-resistant Depression: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Psychol. Med. 49 (4), 655–663. 10.1017/S0033291718001356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanches R. F.; de Lima Osório F.; dos Santos R. G.; Macedo L. R.; Maia-de-Oliveira J. P.; Wichert-Ana L.; de Araujo D. B.; Riba J.; Crippa J. A.; Hallak J. E. (2016) Antidepressant Effects of a Single Dose of Ayahuasca in Patients with Recurrent Depression: A SPECT Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 36 (1), 77–81. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths R. R.; Johnson M. W.; Carducci M. A.; Umbricht A.; Richards W. A.; Richards B. D.; Cosimano M. P.; Klinedinst M. A. (2016) Psilocybin Produces Substantial and Sustained Decreases in Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Life-Threatening Cancer: A Randomized Double-blind Trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 30 (12), 1181–1197. 10.1177/0269881116675513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S.; Bossis A.; Guss J.; Agin-Liebes G.; Malone T.; Cohen B.; Mennenga S. E.; Belser A.; Kalliontzi K.; Babb J.; Su Z.; Corby P.; Schmidt B. L. (2016) Rapid and Sustained Symptom Reduction Following Psilocybin Treatment for Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Life-threatening Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 30 (12), 1165–1180. 10.1177/0269881116675512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschutz M. P.; Forcehimes A. A.; Pommy J. A.; Wilcox C. E.; Barbosa P.; Strassman R. J. (2015) Psilocybin-assisted Treatment for Alcohol Dependence: A Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Psychopharmacol. 29 (3), 289–299. 10.1177/0269881114565144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs T. S.; Johansen P. Ø. (2012) Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) for Alcoholism: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Psychopharmacol. 26 (7), 994–1002. 10.1177/0269881112439253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. W.; Garcia-Romeu A.; Cosimano M. P.; Griffiths R. R. (2014) Pilot Study of the 5-ht2ar Agonist Psilocybin in the Treatment of Tobacco Addiction. J. Psychopharmacol. 28 (11), 983–992. 10.1177/0269881114548296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. W.; Garcia-Romeu A.; Griffiths R. R. (2017) Long-Term Follow-Up of Psilocybin-Facilitated Smoking Cessation. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 43 (1), 55–60. 10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno F. A.; Wiegand C. B.; Taitano E. K.; Delgado P. L. (2006) Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Psilocybin in 9 Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67 (11), 1735–1740. 10.4088/JCP.v67n1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker E. F. W. (1964) The Use of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) In Psychotherapy. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 91 (23), 1200–1202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeifman R. J.; Palhano-Fontes F.; Hallak J.; Arcoverde E.; Maia-Oliveira J. P.; de Araujo D. B. (2019) The Impact of Ayahuasca on Suicidality: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1325. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeifman R. J.; Singhal N.; dos Santos R. G.; Sanches R. F.; de Lima Osório F.; Hallak J. E.; Weissman C. R. (2021) Rapid and Sustained Decreases in Suicidality Following a Single Dose of Ayahuasca among Individuals with Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder: Results from an Open-Label Trial. Psychopharmacology 238, 453–459. 10.1007/s00213-020-05692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]