Abstract

The development of highly selective and fast biocompatible reactions for ligation and cleavage has paved the way for new diagnostic and therapeutic applications of pretargeted in vivo chemistry. The concept of bioorthogonal pretargeting has attracted considerable interest, in particular for the targeted delivery of radionuclides and drugs. In nuclear medicine, pretargeting can provide increased target-to-background ratios at early time-points compared to traditional approaches. This reduces the radiation burden to healthy tissue and, depending on the selected radionuclide, enables better imaging contrast or higher therapeutic efficiency. Moreover, bioorthogonally triggered cleavage of pretargeted antibody–drug conjugates represents an emerging strategy to achieve controlled release and locally increased drug concentrations. The toolbox of bioorthogonal reactions has significantly expanded in the past decade, with the tetrazine ligation being the fastest and one of the most versatile in vivo chemistries. Progress in the field, however, relies heavily on the development and evaluation of (radio)labeled compounds, preventing the use of compound libraries for systematic studies. The rational design of tetrazine probes and triggers has thus been impeded by the limited understanding of the impact of structural parameters on the in vivo ligation performance. In this work, we describe the development of a pretargeted blocking assay that allows for the investigation of the in vivo fate of a structurally diverse library of 45 unlabeled tetrazines and their capability to reach and react with pretargeted trans-cyclooctene (TCO)-modified antibodies in tumor-bearing mice. This study enabled us to assess the correlation of click reactivity and lipophilicity of tetrazines with their in vivo performance. In particular, high rate constants (>50 000 M–1 s–1) for the reaction with TCO and low calculated logD7.4 values (below −3) of the tetrazine were identified as strong indicators for successful pretargeting. Radiolabeling gave access to a set of selected 18F-labeled tetrazines, including highly reactive scaffolds, which were used in pretargeted PET imaging studies to confirm the results from the blocking study. These insights thus enable the rational design of tetrazine probes for in vivo application and will thereby assist the clinical translation of bioorthogonal pretargeting.

Keywords: bioorthogonal chemistry, tetrazine ligation, pretargeted imaging, PET, fluorine-18, molecular imaging

The concept of in vivo chemistry based on the development of bioorthogonal reactions has led to a renaissance of pretargeting strategies in nuclear medicine and for controlled drug delivery.1−4 Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have found widespread application in this regard, particularly as selective targeting vectors for specific antigens expressed on cancer cells.5 For example, immuno-positron emission tomography (PET) can be used for precision medicine, i.e., to guide the selection of patients who show the highest probability to benefit from a specific therapy.6,7 Similarly, radioimmunotherapy (RIT) is based on the application of the unique targeting ability of mAbs to deliver therapeutic radionuclides to diseased tissue, most often to tumors.8 RIT has several advantages over conventional external radiation therapy, notably the ability to target and treat the entire tumor burden, including micrometastases.8 However, due to the long blood circulation time of mAbs (several days to weeks), adequate tumor-to-background ratios are usually not achieved until 2–4 days after administration, requiring the use of long-lived radionuclides. Most often, this results in a relatively high radiation burden to the patient.9,10 In order to reduce the absorbed radiation dose and reach higher tumor-to-background ratios at earlier time-points, pretargeting has emerged as an efficient strategy, enabling in vivo radiolabeling of mAbs upon accumulation at their target.2,10−16 This is realized by modifying the mAb with a specific reactive molecular tag, which can later selectively react with a radiolabeled agent via a rapid bioorthogonal reaction. Similarly, pretargeting can be applied for spatiotemporally controlled drug delivery.2,17−21 In this approach, a highly potent drug is bioorthogonally cleaved from a pretargeted mAb conjugate upon its accumulation at the site of disease, achieving higher local drug concentrations while simultaneously reducing systemic toxicity to healthy tissue. Due to its fast reaction kinetics, high selectivity and biocompatibility, the inverse electron demand Diels–Alder (IEDDA)-initiated ligation between a 1,2,4,5-tetrazine (Tz) and a trans-cyclooctene (TCO) has become state-of-the-art for time-critical application of in vivo chemistry as well as bioorthogonally controlled drug delivery by using Tz-triggered elimination of cleavable TCOs (click-to-release).2,13,19−24 Currently, the understanding of the scope and limitations of IEDDA-initiated ligation for pretargeting strategies in vivo is limited, and the design of suitable Tz-derivatives for this purpose is mainly a “trial-and-error” game, heavily depending on the time-intensive development of radiolabeled compounds for in vivo evaluation. Current labeling strategies have, so far, mostly been focused on chelator approaches, overall impeding the use of compound libraries for systematic studies.14,25,26 In order to enable the rational design of Tz-derivatives for in vivo chemistry, it is important to understand the structure–property relationship between the physicochemical parameters of Tz-derivatives and their capability to reach and react in vivo with TCO-modified (bio)molecules accumulated at the target site of interest.

The aim of the present study was to identify and explore the key parameters that influence the in vivo performance of a Tz (Figure 1). Consequently, we prepared a library of Tz-derivatives with a set of different rate constants (in the reaction with TCO), lipophilicities, and topological polar surface areas (TPSAs) and applied a pretargeted blocking assay to evaluate their ligation performance in vivo. The blocking effect of each Tz was correlated with its lipophilicity (calculated logD7.4 (clogD7.4) values), calculated TPSA, as well as IEDDA reactivity. The obtained results were verified by in vivo pretargeted PET imaging of a set of selected Tz-derivatives radiolabeled with fluorine-18.

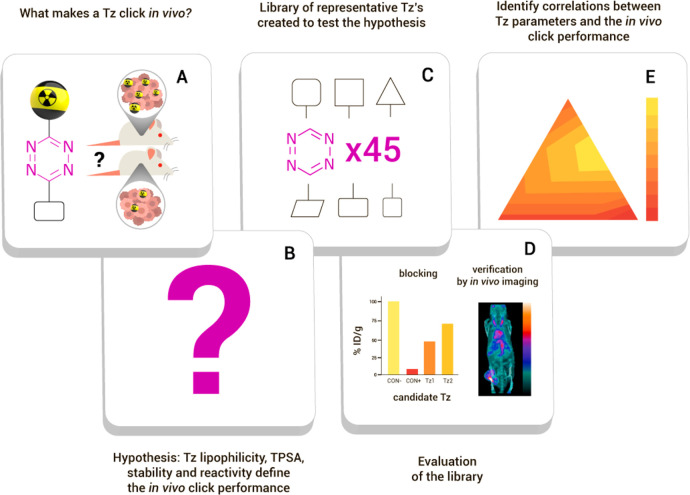

Figure 1.

General strategy and workflow of this study. (A) The research question: Which key parameters determine the efficiency of the in vivo performance of tetrazines? (B) We hypothesized that lipophilicity, TPSA, stability, and/or reactivity of the Tz determine its in vivo ligation efficiency. (C) To test this hypothesis, a compound library was created and (D) evaluated with emphasis on the capability for in vivo click reaction. (E) Finally, these results were analyzed to identify and confirm the correlation between key parameters and in vivo ligation performance.

Results and Discussion

Experimental Design and Preparation of the Tz-Library

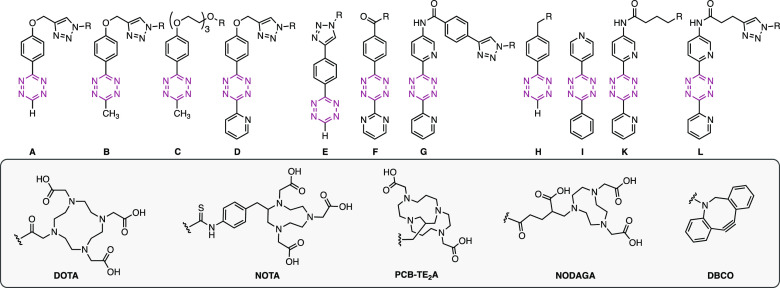

A structurally diverse library of 45 Tz-derivatives was prepared, covering a wide spectrum of physicochemical properties, in particular, calculated TPSAs between 60–350 Å2 and different lipophilicities, with calculated logD7.4 values (clogD7.4) ranging from approximately −7.0 to 2.5 (Table 1; for synthetic procedures and details, see the Supporting Information). The Tz-scaffolds (A–L) include mono- and disubstituted methyl-, phenyl-, 2-pyrimidyl-, and 2-pyridyl-substituted Tz-derivatives with second-order rate constants for the reaction with TCO ranging from 1.4 to 230 M–1 s–1 in 1,4-dioxane at 25 °C and from 1100 to 73 000 M–1 s–1 in buffered aqueous solution at 37 °C. Table 1 provides an overview of the synthesized Tz-library and displays the measured rate constants and calculated physicochemical properties of each Tz. Several compounds were obtained as copper(II) complexes (for details, see the Supporting Information), which was taken into account in the calculation of clogD7.4 and TPSA (as described in the Notes of Table 1).

Table 1. Structural Scaffolds, Calculated Physicochemical Properties (TPSA and clogD7.4), Measured Second-Order Rate Constants for the Ligation with TCO, and Blocking Efficiencies of All Investigated Tz-derivatives.

Notes: The distribution coefficient at physiological pH (logD7.4) and TPSA were calculated using the software Chemicalize. Tetrazines conjugated to DOTA were calculated with chelated trivalent cations, and Tzs with other chelators were calculated with bivalent cations.

Second-order rate constants for the Tz-scaffolds A–L were determined by stopped-flow spectrophotometry (n ≥ 4), monitoring the reaction of representative tetrazines with unsubstituted trans-cyclooctene (TCO) at 25 °C in 1,4-dioxane and with TCO-PEG4 (modified TCO-5ax–OH, “minor-TCO”) in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DBPS) at 37 °C.

Blocking data from ref (48).

Pretargeted Blocking Studies

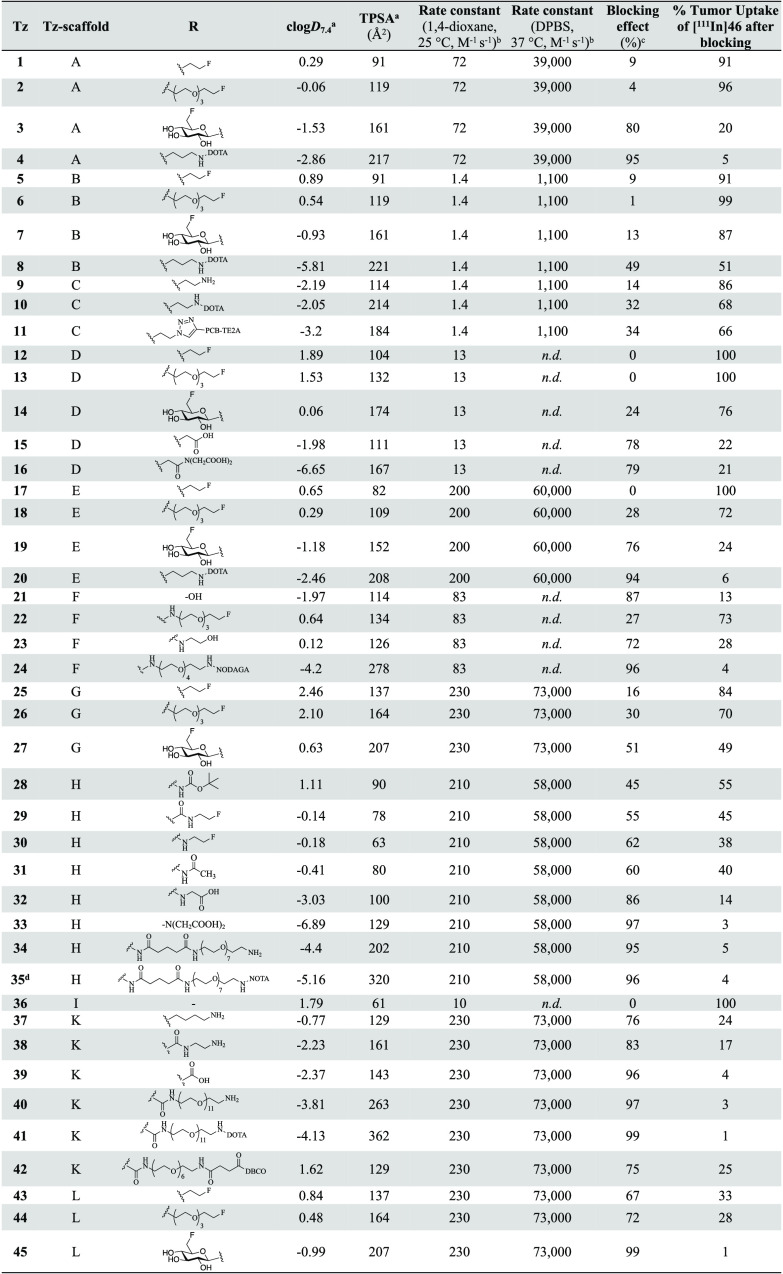

The blocking assay allows for the assessment of the in vivo ligation performance of unlabeled Tz-derivatives, avoiding the need for time-consuming development of radiolabeling procedures as well as the preparation of labeled analogues or surrogates. The assay was inspired by receptor blocking experiments and based on the pretargeted imaging approach reported by Rossin et al.13,27 An 111In-labeled Tz ([111In]46, see Supporting Information, Figure S1) was used in pair with TCO-modified CC49, a noninternalizing mAb that targets the tumor-associated glycoprotein 72 (TAG72),13,27 as a benchmark model for the in vivo ligation. The TCO-modification of CC49 was carried out according to Rossin et al.(13,27) To study the in vivo ligation performance of Tz-derivatives 1–45, BALB/c nude mice bearing LS174T colon carcinoma xenografts were injected intravenously (i.v.) with CC49-TCO 72 h prior to i.v. injection of the unlabeled Tz, followed by administration of [111In]46 1 h later (for experimental details, see the Supporting Information). The animals were euthanized after 22 h, and an ex vivo biodistribution was carried out to quantify the tumor uptake of [111In]46 (Figure 2A). The efficiency of the in vivo ligation of the unlabeled Tz can thus be correlated to a reduced uptake of [111In]46 (Figure 2A). As a control, blocking was performed using the nonradioactive precursor of [111In]46 (DOTA-Tz 41, see the Supporting Information), which blocked ≥96% of the [111In]46 tumor uptake. A group of CC49-TCO-pretreated mice were injected exclusively with [111In]46 (without blocking), and the determined uptake was used as reference value (100%) to normalize the observed changes in tumor uptake in blocking experiments.

Figure 2.

Results from the blocking assay. (A) Schematic display of the blocking assay. (B) The blocking effect of nonradiolabeled Tz was determined as the change in tumor uptake of [111In]46 22 h p.i. Each Tz was administered 1 h prior to [111In]46, and the uptake was normalized to a group of animals in which no blocking was performed (control). Data represent mean from n = 3 mice/group; detailed information can be found in the SI. (C,D) Correlation of blocking effect and clogD7.4 for Tz-derivatives with similar IEDDA reactivity. Data was fitted to exponential growth equation Y = Y0ekx (dotted line). (E) Statistical analysis of the correlation between tumor uptake and clogD7.4 for the different groups of Tz-derivatives. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) describes the goodness of fit between the blocking effect and clogD7.4. Notes: aReaction of representative Tz with unsubstituted TCO. bReaction of representative Tz with TCO-PEG4. cMeasured for Tz-scaffold A only. n.d. = not determined.

Figure 2A displays the blocking assay, and Figure 2B summarizes the results for the entire Tz-library in the assay. The highest blocking efficiencies (95–99%) were observed for the Tz–chelator conjugates 4, 24, 35, and 41, the Tz–carboxylic acids 33 and 39, the Tz–PEG derivative 40, and the Tz–sugar conjugate 45. All of these probes include H-phenyl-, pyrimidyl-phenyl-, or bis(pyridyl)-Tz-scaffolds with second-order rate constants for the reaction with TCO of >70 M–1 s–1 (1,4-dioxane, 25 °C) or of >39 000 M–1 s–1 (DPBS, 37 °C) (cf. Table 1). Further details of the blocking studies are provided in the Supporting Information (Figure S2). Next, potential correlations between the blocking effect, the clogD7.4 and the TPSA, as well as the IEDDA reactivity were investigated. As expected, high IEDDA reactivity was shown to directly correlate with the blocking effect and thus confirmed to be a key parameter for the in vivo ligation performance of Tz-derivatives (Figure 2C,D). We did not observe a strong correlation between the blocking effect and TPSA (Figure S14). However, a distinct relationship between clogD7.4 values and the blocking effect was evidently observed when comparing Tz-derivatives with similar IEDDA reactivity (Figures 2C,D and S15). For all Tz-scaffolds, a Pearson’s correlation coefficient >0.78 was found. Our results show that high IEDDA reactivity (>50 000 M–1 s–1) and a clogD7.4 of −3 or lower are strong indicators for high in vivo ligation performance of Tz-derivatives in pretargeting approaches using the described tumor model (Figure 2).

Experimental Design of a [18F]Tz-Library

In order to verify that the results from the blocking study can be used to predict the outcome for in vivo PET imaging, 18 Tz-derivatives from the first library were selected. The selection was based on criteria such as the possibility for 18F-labeling, structural diversity, lipophilicities, and distinct IEDDA reactivities. For this purpose, we decided to use an indirect radiolabeling approach, enabling the combination of different building blocks to rapidly access a series of 18F-labeled Tz-derivatives. The Cu-catalyzed azide–alkyne [3 + 2] cycloaddition (CuAAC) appeared to be suitable in this respect, as it allows for fast and efficient radiolabeling under mild reaction conditions.28−32 Six precursor Tz–alkynes (I–VI) were prepared and reacted with three 18F-labeled azides ([18F]Az1–Az3) to obtain 18 different [18F]Tz-probes (Table 2).

Table 2. Cu-Mediated Click-Radiolabeling for the Synthesis of 18F-Labeled Tz-Probes.

| tetrazine | Tz–alkyne (I–VI) | azide-functionalized 18F click agent | RCY (%)a | Amb (GBq/μmol) | RCP (%)c | in vivo stabilityd (% intact [18F]Tz after 30 min) | blocking effect (%) (of unlabeled Tz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18F]1 | IV | [18F]Az1 | 25c | 55 | 99 | 90 | 9 |

| [18F]2 | IV | [18F]Az2 | 23 | 22 | 96 | 37 | 4 |

| [18F]3 | IV | [18F]Az3 | 61 | 31 | 98 | 76 | 81 |

| [18F]5 | VI | [18F]Az1 | 14* | 106 | ≥99 | 26 | 10 |

| [18F]6 | VI | [18F]Az2 | 33 | 100 | ≥99 | 85 | 1 |

| [18F]7 | VI | [18F]Az3 | 52 | 230 | ≥99 | 60 | 3 |

| [18F]12 | V | [18F]Az1 | 1* | 107 | 96 | 10 | 0 |

| [18F]13 | V | [18F]Az2 | 11 | 21 | 94 | 16 | 0 |

| [18F]14 | V | [18F]Az3 | 68 | 102 | 98 | 43 | 24 |

| [18F]17 | III | [18F]Az1 | 8* | 209 | 98 | 32 | 0 |

| [18F]18 | III | [18F]Az2 | 17 | 37 | 92 | 22 | 29 |

| [18F]19 | III | [18F]Az3 | 59 | 29 | 98 | 87 | 76 |

| [18F]25 | II | [18F]Az1 | 16* | n.d. | 83 | n.d. | 16 |

| [18F]26 | II | [18F]Az2 | 36 | 54 | ≥85 | 27 | 30 |

| [18F]27 | II | [18F]Az3 | 18* | n.d. | ≥90 | n.d. | 51 |

| [18F]43 | I | [18F]Az1 | 1 | 5 | 90 | 10 | 67 |

| [18F]44 | I | [18F]Az2 | 20 | 85 | 98 | n.d. | 72 |

| [18F]45 | I | [18F]Az3 | 11 | 151 | ≥90 | 42 | 99 |

Notes: Details on experimental procedures are provided in the Supporting Information. RCYs were decay-corrected to the starting amount of radioactivity for the respective azide, or *RCY was determined starting from 18F–.

Molar activities (Am) differ due to the use of different cyclotrons (see Supporting Information).

RCP was determined by radio-HPLC.

In vivo stability of [18F]Tz was assessed by determining the fraction (%) of radioactivity corresponding to intact compound after 30 min (n = 4) from radio-TLC analysis. n.d. = not determined.

Indirect 18F-Labeling of a Tz Series via Cu-Catalyzed Click Chemistry

Azide building blocks were 18F-labeled using fully automated procedures to afford [18F]Az1–[18F]Az3 (Scheme S15),33,34 and Tz–alkynes I–VI were synthesized as described in the Supporting Information. Subsequent radiolabeling via the CuAAC was achieved in various yields, up to approximately 70% (Table 2). Applied conditions for the CuAAC differed depending on the substituents attached to the Tz-scaffold. In general, radiolabeling was carried out at room temperature with reaction times of 10–15 min using aqueous solutions of CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, and disodium bathophenanthroline disulfonate (BPDS). For the synthesis of the bis(pyridyl)Tz-derivatives [18F]25, [18F]44, and [18F]45, increased amounts of the catalysts, longer reaction times (20–25 min), and elevated temperatures (120 °C) were required in order to reach radiochemical conversions (RCCs) of ≥70%. A possible reason for the harsher conditions required for this scaffold may be a result from coordination of Cu by the bis(pyridyl)-Tz-moiety. Radiochemical yields (RCYs) and molar activities (Am) for all 18F-labeled Tz-derivatives are presented in Table 2. Radiochemical purities (RCPs) of the isolated compounds were high (>90%), except for [18F]25 and[18F]26 (83–85%) due to radiolysis (observed for [18F]25), undesired decomposition, and difficult separation of the resulting byproducts. During the radiolabeling, partial reduction of [18F]19 and [18F]44 to the corresponding dihydro-Tz (cf. Figures S73 and S74) was observed. However, these Tz-derivatives were reoxidized using phenyliodonium diacetate (PIDA). In the case of [18F]44, complete reduction to the dihydro-Tz (using ascorbic acid) and reoxidation upon purification was applied to prevent radiolysis. Excess PIDA and byproducts were removed during solid-phase extraction to obtain [18F]44 in an RCP of 98% (Table 2; for details see the Supporting Information). Moreover, during the synthesis of [18F]45, an alternative deprotection method for the azide ([18F]Az3) was required to avoid decomposition of the Tz-scaffold during the CuAAC. All 18F-labeled Tz-derivatives were formulated in 0.9% saline prior further studies. Overall, radiofluorination via the CuAAC allowed for the preparation of a structurally diverse series of 18F-labeled Tz-derivatives. In contrast to routinely used direct radiofluorination methods, this building block approach gave access to highly reactive [18F]Tz-probes, using Tz-scaffolds that have previously been reported to be inaccessible.1,35,36

In Vivo Stability of 18F-Labeled Tz-derivatives in Naïve Mice

Next, we investigated whether there is a relationship between the in vivo stability of Tz-derivatives and their blocking ability. A total of 15 18F-labeled tetrazines were studied in naïve mice. Blood was collected after 30 min, and plasma samples were analyzed by radio-TLC (for details, see the Supporting Information) for stability assessment (Table 2 and Figures S75 and S76). Interestingly, the in vivo stability 30 min p.i. had only a limited or even no effect on the in vivo ligation performance as evaluated in the blocking study (cf. Table 1). Consequently, six [18F]Tz ([18F]1, [18F]3, [18F]19, [18F]26, [18F]44, and [18F]45) were selected for further in vivo studies solely based on the IEDDA reactivity (second-order rate constants between 72 and 230 M–1 s–1) and lipophilicity (clogD7.4 between −1.53 and 2.10). These radiolabeled Tz-probes were used to investigate if the results from the blocking assay can be translated to pretargeted PET imaging at tracer doses.

Pretargeted PET Imaging

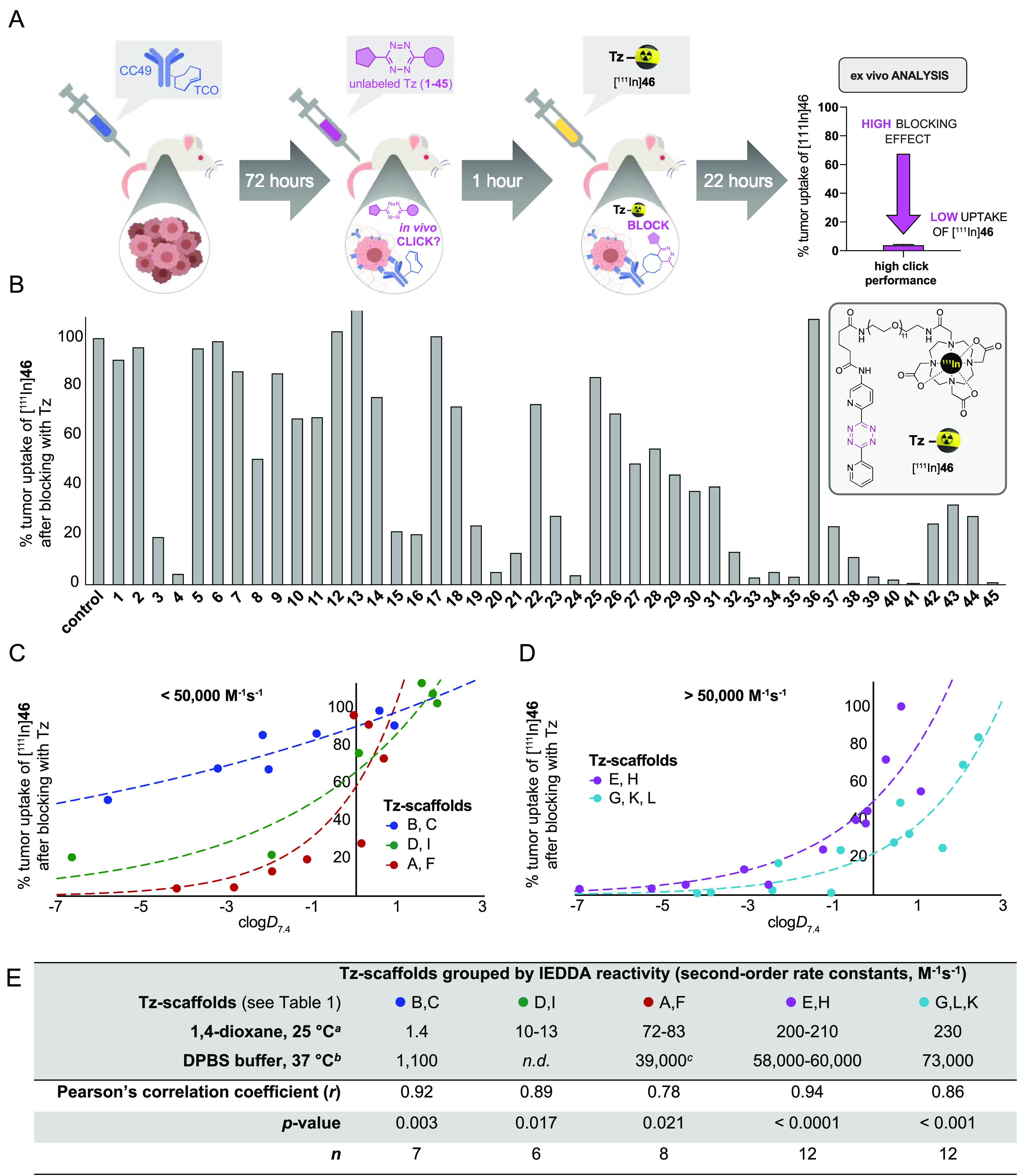

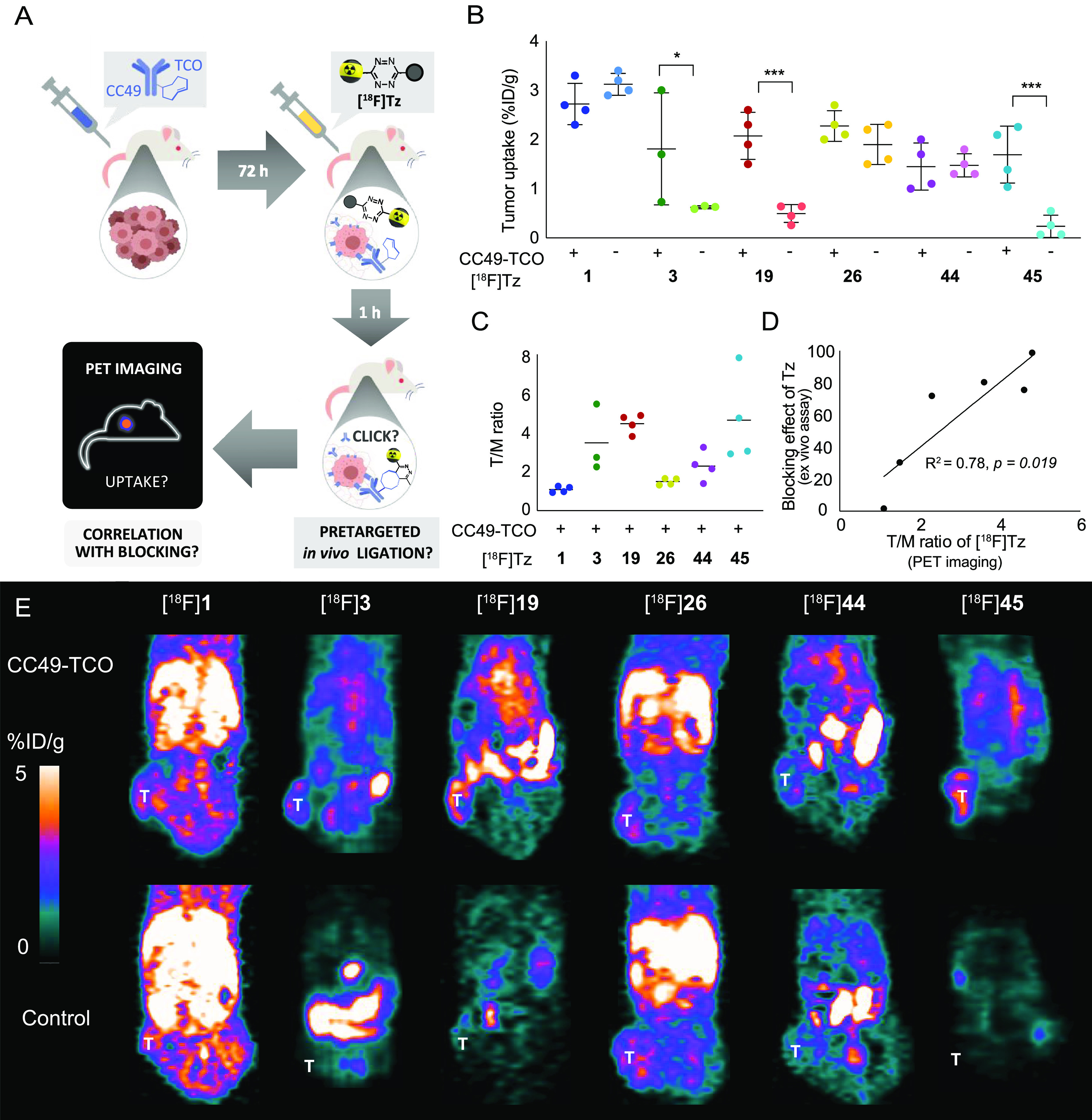

Of the six Tz-probes selected for evaluation in pretargeted PET imaging studies, four compounds (3, 19, 44, and 45) showed a good to excellent blocking effect (72–99%), while two probes (1 and 26) only showed a limited effect (9% for 1 and 30% for 26). The latter were included to verify that blocking results can reliably be used to predict the capability of radiolabeled Tz for pretargeted in vivo chemistry.

Mice (n = 3–4 per group) were injected i.v. with either CC49-TCO or 0.9% saline (control experiments). After 72 h, 18F-labeled Tz (5–10 MBq) was administered, and the mice were PET/CT-scanned 1 h p.i. A 3D region of interest (ROI) was created on the entire tumor volume as well as heart and muscle tissue, and the uptake was quantified as a percentage of the injected dose per gram (mean% ID/g) as well as the tumor-to-blood (T/B) and tumor-to-muscle (T/M) ratios (Figure 3A–D, Table S3 and S4).

Figure 3.

Pretargeted PET imaging in BALB/c nude mice bearing LS174T tumor xenografts with six 18F-labeled Tz-derivatives. Animals were treated with CC49-TCO or saline (control) 72 h prior to injection of the radiolabeled Tz-derivative. (A) Schematic illustration of the pretargeting experiment and the research question: Is there a correlation between the blocking effect and the PET imaging contras? (B) Image-derived mean uptake values are presented as a percentage of the injected dose per gram (%ID/g) in a tumor 1h p.i. (C) Tumor-to-muscle (T/M) ratios (n = 4 mice, except for [18F]3, n = 3). Data is represented as mean ± SD (*p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001). For all groups, n = 4 mice (except [18F]3 where n = 3) (D) Correlation between the blocking effect of the unlabeled Tz-derivatives 1, 3, 19, 26, 44, and 45 and the T/M ratios (mean) for the corresponding 18F-labeled compounds observed by in vivo pretargeted PET imaging. A strong correlation was found (linear regression: R2 = 0.78, p = 0.019, n = 6). Data is represented as mean ± SD. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (* p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001) when compared to control. (E) Representative images of PET scans 1 h p.i. of the radiolabeled Tz ([18F]1, [18F]3, [18F]19, [18F]26, [18F]44, and [18F]45) in pretargeted PET imaging studies (T indicates the position of the tumor). [18F]3, [18F]19, and [18F]45 displayed specific tumor uptake, and the tumor is clearly visualized in the PET image.

The tumor uptake of the different 18F-labeled Tz-probes was at a rather similar level; however, [18F]3, [18F]19, and [18F]45 showed a significantly increased tumor accumulation in mice pretreated with CC49-TCO compared to control animals (Figure 3A,F and Tables S3 and S4). As expected and in accordance with blocking results, there was no significant difference in tumor uptake between pretargeting experiments and controls for [18F]1 and [18F]26. In the case of [18F]44, no increase in tumor accumulation was observed in mice pretreated with TCO-modified mAb. However, this Tz showed higher radioactivity levels in the heart in mice pretreated with CC49-TCO compared to controls (2.5 ± 0.7 and 1.5 ± 0.2%ID/g, respectively; Figure 3B and Table S1). This indicates that [18F]44 binds to mAb still circulating in the blood pool. This difference was also observed for the three 18F-labeled Tz-derivatives showing specific tumor accumulation ([18F]3,[18F]19, and [18F]45), but not for the nonaccumulating probes [18F]1 and [18F]26 (Figure 3B). Binding to residual mAb in the blood pool is a frequently reported challenge in pretargeted imaging approaches and has been addressed by the development of clearing agents.14,37−39 However, ligation in blood did not hinder the investigation of the in vivo ligation performance of 18F-labeled Tz-probes in comparison to blocking efficiencies.

Finally, the relationship between the in vivo performance of the used Tz-probes and the results obtained from the blocking assay was investigated. A strong correlation was found between the blocking effect of the unlabeled Tz and the T/M ratio (Figure 3D) as well as the selective tumor uptake (tumor to tumor-control (T/Tc) ratio) (Figure S78 and Table S4) of the respective 18F-labeled probes in pretargeted PET imaging studies. These significant relationships confirm the validity of the blocking assay and our finding that reduced lipophilicity and high IEDDA reactivity are key parameters for the in vivo performance of Tz-derivatives. Our results show that low lipophilicity enhances the ability of the bioorthogonal Tz-agent to bind to TCO–mAbs at the tumor site. Moreover, faster excretion of radiolabeled probes, which is crucial for obtaining high tumor-to-background ratios, is also facilitated by the low lipophilicity of Tz-derivatives (Figure 3).

Conclusion

The advancement of in vivo chemical tools based on a better understanding of the scope and limitations of bioorthogonal reactions, in vitro and in living systems, paves the way to clinical translation of pretargeting approaches for diagnostic (e.g., pretargeted imaging29,36,38,40−46) and therapeutic application (e.g., pretargeted radionuclide therapy1,16,19,20,47 or bioorthogonal cleavage of antibody–drug conjugates2,17,18). However, progress in this field is limited due to the required elaborate development of (radio)labeled compounds for in vivo evaluation, hampering the use of compound libraries for systematic studies to gain further insight. The developed blocking assay described herein tackles this challenge. By screening of 45 unlabeled Tz-derivatives, we were able to reveal the key parameters that are necessary for a Tz to be applied in pretargeting. High IEDDA reactivity of the Tz-scaffold with a second-order rate constant of >50 000 M–1 s–1 was shown to be an important parameter to achieve efficient in vivo ligation (>96% blocking) to pretargeted mAb–TCO conjugates in LS174T xenografts. Unexpectedly, reduced lipophilicity was identified to play an even more decisive role, with clogD7.4 values being a strong indicator for the in vivo ligation performance of Tz-derivatives. In particular, clogD7.4 values below −3 increased the chances for successful in vivo ligation in the applied tumor model. These key findings from the blocking study were confirmed by pretargeted PET imaging. The increasing knowledge regarding the IEDDA reactivity of various Tz-scaffolds as well as the fact that calculated parameters (i.e., clogD7.4) can be used to guide and accelerate the design and development of Tz-derivatives for in vivo applications.

Overall, we present and demonstrate a new strategy and method for the systematic investigation of bioorthogonal pretargeting. The concept of our blocking assay can be translated to other tumor models and/or targets, in combination with respective mAbs as targeting vectors/carriers. We believe that the revealed key parameters enable the development of Tz-derivatives as multifunctional tools for diagnostic and therapeutic applications, ultimately to improve and accelerate the clinical translation of in vivo chemistry.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Union’s EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020, under grant agreements no. 670261 and 668532. VS was supported by BRIDGE – Translational Excellence Programme at the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant agreement no. NNF18SA0034956). The Lundbeck Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Innovation Fund Denmark, The Carlsberg Foundation (CF18-0126), the Danish Cancer Society, the Arvid Nilsson Foundation, the Svend Andersen Foundation, the Neye Foundation, the Research Foundation of Rigshospitalet, the Danish National Research Foundation (grant 126), the Research Council of the Capital Region, and the Research Council for Independent Research are further acknowledged. Ida Nymann Petersen, Giorgos Kougioumtzoglou, and Placid Nnamdi Orji are thanked for technical assistance.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsptsci.1c00007.

Author Contributions

⊥ EJLS, JTJ, and CD contributed equally to the work.

Author Contributions

The experimental work was carried out through contributions of EJLS, JTJ, CD, UMB, KN, PEE, KB, VS, MW, DS, CBMP, LH, MS, TW, and RR. The study was designed by EJLS, JTJ, CD, UMB, KN, PEE, MR, JLK, HM, AK, and MMH. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

All animal experiments in this study were approved by national animal welfare committees in Austria and Denmark, and the experiments were performed in accordance with European guidelines.

Supplementary Material

References

- Steen E. J. L.; Edem P. E.; Norregaard K.; Jorgensen J. T.; Shalgunov V.; Kjaer A.; Herth M. M. (2018) Pretargeting in nuclear imaging and radionuclide therapy: Improving efficacy of theranostics and nanomedicines. Biomaterials 179, 209–245. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin R.; Versteegen R. M.; Wu J.; Khasanov A.; Wessels H. J.; Steenbergen E. J.; Ten Hoeve W.; Janssen H. M.; van Onzen A.; Hudson P. J.; Robillard M. S. (2018) Chemically triggered drug release from an antibody-drug conjugate leads to potent antitumour activity in mice. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 1484. 10.1038/s41467-018-03880-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapuarachchige S.; Artemov D. (2020) Theranostic Pretargeting Drug Delivery and Imaging Platforms in Cancer Precision Medicine. Front. Oncol. 10, 1131. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altai M.; Membreno R.; Cook B.; Tolmachev V.; Zeglis B. M. (2017) Pretargeted Imaging and Therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 58 (10), 1553–1559. 10.2967/jnumed.117.189944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A. M.; Wolchok J. D.; Old L. J. (2012) Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12 (4), 278–87. 10.1038/nrc3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen G. A.; Visser G. W.; Lub-De Hooge M. N.; de Vries E. G.; Perk L. R. (2007) Immuno-PET: a navigator in monoclonal antibody development and applications. Oncologist 12 (12), 1379–89. 10.1634/theoncologist.12-12-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell C. A.; Brechbiel M. W. (2007) Development of radioimmunotherapeutic and diagnostic antibodies: an inside-out view. Nucl. Med. Biol. 34 (7), 757–78. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson S. M.; Carrasquillo J. A.; Cheung N. K.; Press O. W. (2015) Radioimmuno-therapy of human tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15 (6), 347–60. 10.1038/nrc3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjesson P. K.; Jauw Y. W.; de Bree R.; Roos J. C.; Castelijns J. A.; Leemans C. R.; van Dongen G. A.; Boellaard R. (2009) Radiation dosimetry of89Zr-labeled chimeric monoclonal antibody U36 as used for immuno-PET in head and neck cancer patients. J. Nucl. Med. 50 (11), 1828–36. 10.2967/jnumed.109.065862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkers E. C.; Oude Munnink T. H.; Kosterink J. G.; Brouwers A. H.; Jager P. L.; de Jong J. R.; van Dongen G. A.; Schroder C. P.; Lub-De Hooge M. N.; de Vries E. G. (2010) Biodistribution of 89Zr-trastuzumab and PET imaging of HER2-positive lesions in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 87 (5), 586–92. 10.1038/clpt.2010.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardan D. T.; Meares C. F.; Goodwin D. A.; McTigue M.; David G. S.; Stone M. R.; Leung J. P.; Bartholomew R. M.; Frincke J. M. (1985) Antibodies against metal chelates. Nature 316 (6025), 265–8. 10.1038/316265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin D. A.; Mears C. F.; McTigue M.; David G. S. (1986) Monoclonal antibody hapten radiopharmaceutical delivery. Nucl. Med. Commun. 7 (8), 569–80. 10.1097/00006231-198608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin R.; Renart Verkerk P.; van den Bosch S. M.; Vulders R. C.; Verel I.; Lub J.; Robillard M. S. (2010) In vivo chemistry for pretargeted tumor imaging in live mice. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49 (19), 3375. 10.1002/anie.200906294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeglis B. M.; Brand C.; Abdel-Atti D.; Carnazza K. E.; Cook B. E.; Carlin S.; Reiner T.; Lewis J. S. (2015) Optimization of a Pretargeted Strategy for the PET Imaging of Colorectal Carcinoma via the Modulation of Radioligand Pharmacokinetics. Mol. Pharmaceutics 12 (10), 3575–87. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin R.; Lappchen T.; van den Bosch S. M.; Laforest R.; Robillard M. S. (2013) Diels-Alder reaction for tumor pretargeting: in vivo chemistry can boost tumor radiation dose compared with directly labeled antibody. J. Nucl. Med. 54 (11), 1989–95. 10.2967/jnumed.113.123745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keinanen O.; Fung K.; Brennan J. M.; Zia N.; Harris M.; van Dam E.; Biggin C.; Hedt A.; Stoner J.; Donnelly P. S.; Lewis J. S.; Zeglis B. M. (2020) Harnessing (64)Cu/(67)Cu for a theranostic approach to pretargeted radioimmunotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117 (45), 28316–27. 10.1073/pnas.2009960117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ediriweera G. R.; Simpson J. D.; Fuchs A. V.; Venkatachalam T. K.; Van De Walle M.; Howard C. B.; Mahler S. M.; Blinco J. P.; Fletcher N. L.; Houston Z. H.; Bell C. A.; Thurecht K. J. (2020) Targeted and modular architectural polymers employing bioorthogonal chemistry for quantitative therapeutic delivery. Chem. Sci. 11 (12), 3268–80. 10.1039/D0SC00078G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I.; Agris P. F.; Yigit M. V.; Royzen M. (2016) In situ activation of a doxorubicin prodrug using imaging-capable nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 52 (36), 6174–77. 10.1039/C6CC01024E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkovitsch M.; Haider M.; Sohr B.; Herrmann B.; Klubnick J.; Weissleder R.; Carlson J. C. T.; Mikula H. (2020) A Cleavable C2-Symmetric trans-Cyclooctene Enables Fast and Complete Bioorthogonal Disassembly of Molecular Probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (45), 19132–41. 10.1021/jacs.0c07922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J. C. T.; Mikula H.; Weissleder R. (2018) Unraveling Tetrazine-Triggered Bioorthogonal Elimination Enables Chemical Tools for Ultrafast Release and Universal Cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (10), 3603–12. 10.1021/jacs.7b11217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin R.; van Duijnhoven S. M.; Ten Hoeve W.; Janssen H. M.; Kleijn L. H.; Hoeben F. J.; Versteegen R. M.; Robillard M. S. (2016) Triggered Drug Release from an Antibody-Drug Conjugate Using Fast “Click-to-Release” Chemistry in Mice. Bioconjugate Chem. 27 (7), 1697–706. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteegen R. M.; Rossin R.; Ten Hoeve W.; Janssen H. M.; Robillard M. S. (2013) Click to release: instantaneous doxorubicin elimination upon tetrazine ligation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 52 (52), 14112–6. 10.1002/anie.201305969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman M. L.; Royzen M.; Fox J. M. (2008) Tetrazine ligation: Fast bioconjugation based on inverse-electron-demand Diels-Alder reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (41), 13518–9. 10.1021/ja8053805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darko A.; Wallace S.; Dmitrenko O.; Machovina M. M.; Mehl R. A.; Chin J. W.; Fox J. M. (2014) Conformationally strained trans-cyclooctene with improved stability and excellent reactivity in tetrazine ligation. Chem. Sci. 5 (10), 3770–6. 10.1039/C4SC01348D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans H. L.; Nguyen Q. D.; Carroll L. S.; Kaliszczak M.; Twyman F. J.; Spivey A. C.; Aboagye E. O. (2014) A bioorthogonal 68Ga-labelling strategy for rapid in vivo imaging. Chem. Commun. 50 (67), 9557–60. 10.1039/C4CC03903C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeglis B. M.; Sevak K. K.; Reiner T.; Mohindra P.; Carlin S. D.; Zanzonico P.; Weissleder R.; Lewis J. S. (2013) A Pretargeted PET Imaging Strategy Based on Bioorthogonal Diels-Alder Click Chemistry. J. Nucl. Med. 54 (8), 1389–96. 10.2967/jnumed.112.115840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin R.; van den Bosch S. M.; Ten Hoeve W.; Carvelli M.; Versteegen R. M.; Lub J.; Robillard M. S. (2013) Highly reactive trans-cyclooctene tags with improved stability for Diels-Alder chemistry in living systems. Bioconjugate Chem. 24 (7), 1210–7. 10.1021/bc400153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill H. S.; Marik J. (2011) Preparation of 18F-labeled peptides using the copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Nat. Protoc. 6 (11), 1718–25. 10.1038/nprot.2011.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. P.; Adumeau P.; Lewis J. S.; Zeglis B. M. (2016) Click Chemistry and Radiochemistry: The First 10 Years. Bioconjugate Chem. 27 (12), 2791–807. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross T. L.; Honer M.; Lam P. Y. H.; Mindt T. L.; Groehn V.; Schibli R.; Schubiger P. A.; Ametamey S. M. (2008) Fluorine-18 Click Radiosynthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of a New 18F-Labeled Folic Acid Derivative. Bioconjugate Chem. 19 (12), 2462–70. 10.1021/bc800356r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik J.; Sutcliffe J. L. (2006) Click for PET: rapid preparation of [18F]fluoropeptides using Cu-I catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Tetrahedron Lett. 47 (37), 6681–4. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.06.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser M.; Arstad E. (2007) Click labeling” with 2-[18F]fluoroethylazide for positron emission tomography. Bioconjugate Chem. 18 (3), 989–93. 10.1021/bc060301j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk C.; Wilkovitsch M.; Skrinjar P.; Svatunek D.; Mairinger S.; Kuntner C.; Filip T.; Frohlich J.; Wanek T.; Mikula H. (2017) [18F]Fluoroalkyl azides for rapid radiolabeling and (Re)investigation of their potential towards in vivo click chemistry. Org. Biomol. Chem. 15 (28), 5976–82. 10.1039/C7OB00880E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschauer S.; Haubner R.; Kuwert T.; Prante O. (2014) 18F-glyco-RGD peptides for PET imaging of integrin expression: efficient radiosynthesis by click chemistry and modulation of biodistribution by glycosylation. Mol. Pharmaceutics 11 (2), 505–15. 10.1021/mp4004817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Cai H.; Hassink M.; Blackman M. L.; Brown R. C.; Conti P. S.; Fox J. M. (2010) Tetrazine-trans-cyclooctene ligation for the rapid construction of 18F-labeled probes. Chem. Commun. 46 (42), 8043–5. 10.1039/c0cc03078c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk C.; Svatunek D.; Filip T.; Wanek T.; Lumpi D.; Frohlich J.; Kuntner C.; Mikula H. (2014) Development of a 18F-labeled tetrazine with favorable pharmacokinetics for bioorthogonal PET imaging. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 53 (36), 9655–9. 10.1002/anie.201404277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen E. J. L.; Jorgensen J. T.; Johann K.; Norregaard K.; Sohr B.; Svatunek D.; Birke A.; Shalgunov V.; Edem P. E.; Rossin R.; Seidl C.; Schmid F.; Robillard M. S.; Kristensen J. L.; Mikula H.; Barz M.; Kjaer A.; Herth M. M. (2020) Trans-Cyclooctene-Functionalized PeptoBrushes with Improved Reaction Kinetics of the Tetrazine Ligation for Pretargeted Nuclear Imaging. ACS Nano 14 (1), 568–84. 10.1021/acsnano.9b06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. P.; Kozlowski P.; Jackson J.; Cunanan K. M.; Adumeau P.; Dilling T. R.; Zeglis B. M.; Lewis J. S. (2017) Exploring Structural Parameters for Pretargeting Radioligand Optimization. J. Med. Chem. 60 (19), 8201–17. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keinanen O.; Fung K.; Pourat J.; Jallinoja V.; Vivier D.; Pillarsetty N. K.; Airaksinen A. J.; Lewis J. S.; Zeglis B. M.; Sarparanta M. (2017) Pretargeting of internalizing trastuzumab and cetuximab with a 18F-tetrazine tracer in xenograft models. EJNMMI Res. 7 (1), 95. 10.1186/s13550-017-0344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk C.; Svatunek D.; Mairinger S.; Stanek J.; Filip T.; Matscheko D.; Kuntner C.; Wanek T.; Mikula H. (2016) Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of a Low-Molecular-Weight 11C-Labeled Tetrazine for Pretargeted PET Imaging Applying Bioorthogonal in Vivo Click Chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 27 (7), 1707–12. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edem P. E.; Jorgensen J. T.; Norregaard K.; Rossin R.; Yazdani A.; Valliant J. F.; Robillard M.; Herth M. M.; Kjaer A. (2020) Evaluation of a 68Ga-Labeled DOTA-Tetrazine as a PET Alternative to 111In-SPECT Pretargeted Imaging. Molecules 25 (3), 463. 10.3390/molecules25030463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen E. J. L.; Jorgensen J. T.; Petersen I. N.; Norregaard K.; Lehel S.; Shalgunov V.; Birke A.; Edem P. E.; L’Estrade E. T.; Hansen H. D.; Villadsen J.; Erlandsson M.; Ohlsson T.; Yazdani A.; Valliant J. F.; Kristensen J. L.; Barz M.; Knudsen G. M.; Kjaer A.; Herth M. M. (2019) Improved radiosynthesis and preliminary in vivo evaluation of the 11C-labeled tetrazine [11C]AE-1 for pretargeted PET imaging. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 29 (8), 986–90. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. P.; Houghton J. L.; Kozlowski P.; Abdel-Atti D.; Reiner T.; Pillarsetty N. V. K.; Scholz W. W.; Zeglis B. M.; Lewis J. S. (2016) 18F-Based Pretargeted PET Imaging Based on Bioorthogonal Diels Alder Click Chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 27 (2), 298–301. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edem P. E.; Sinnes J. P.; Pektor S.; Bausbacher N.; Rossin R.; Yazdani A.; Miederer M.; Kjaer A.; Valliant J. F.; Robillard M. S.; Rosch F.; Herth M. M. (2019) Evaluation of the inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction in rats using a 44Sc-labelled tetrazine for pretargeted PET imaging. EJNMMI Res. 9, 49. 10.1186/s13550-019-0520-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keinanen O.; Li X. G.; Chenna N. K.; Lumen D.; Ott J.; Molthoff C. F.; Sarparanta M.; Helariutta K.; Vuorinen T.; Windhorst A. D.; Airaksinen A. J. (2016) A New Highly Reactive and Low Lipophilicity Fluorine-18 Labeled Tetrazine Derivative for Pretargeted PET Imaging. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 7 (1), 62–6. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herth M. M.; Andersen V. L.; Lehel S.; Madsen J.; Knudsen G. M.; Kristensen J. L. (2013) Development of a 11C-labeled tetrazine for rapid tetrazine-trans-cyclooctene ligation. Chem. Commun. 49 (36), 3805–7. 10.1039/c3cc41027g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappchen T.; Rossin R.; van Mourik T. R.; Gruntz G.; Hoeben F. J. M.; Versteegen R. M.; Janssen H. M.; Lub J.; Robillard M. S. (2017) DOTA-tetrazine probes with modified linkers for tumor pretargeting. Nucl. Med. Biol. 55, 19–26. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulie C. B. M.; Jørgensen J. T.; Shalgunov V.; Kougioumtzoglou G.; Jeppesen T. E.; Kjaer A.; Herth M. M. (2021) Evaluation of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-PEG7-H-Tz for Pretargeted Imaging in LS174T Xenografts—Comparison to [111In]In-DOTA-PEG11-BisPy-Tz. Molecules 26 (3), 544. 10.3390/molecules26030544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.