Approximately 76% of US youths aged 6 to 17 years do not meet the recommended guidelines for 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day.1 Routine youth physical activity supports healthy habits early in life, with lasting benefits into adulthood, including protection against high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and depression.2 Disparities in MVPA levels exist between White, Hispanic, and Black youths. For example, 49% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 44.4, 53.1) of White youths engage in at least 60 minutes of MVPA at least 5 days per week compared with just 42% (95% CI = 37.7, 46.4) of Black and 45% (95% CI = 41.7, 48.1) of Hispanic youths.1 Similarly, age and income are shown to be significantly associated with youth physical activity.3 Significant declines in MVPA are observed with increasing age, with 43% of elementary school–aged youths compared with 5% of high school–aged youths meeting physical activity guidelines.1 Low-income youths are less likely than high-income youths to participate in organized sports (70% vs 88%), and individuals (children and adults) in high-poverty neighborhoods spend fewer weekly person-hours in community parks compared with those in low-poverty neighborhoods (1380 vs 1690 person-hours, respectively).1 Low rates of MVPA in non-White and low-income youths predict significant disparities in youth health-related physical fitness by race and income,4 as well as chronic health conditions and health inequities throughout the life course.2

Urban planning plays a critical role in the availability and accessibility of both active transportation options, such as walking, running, and biking, and public transportation options, such as city buses or trains. Safe active transportation relies on the presence of high-quality sidewalks, bike lanes, or trails. Similarly, positive physical attributes of the built environment, such as traffic volume and presence of sidewalks, influence levels of youth physical activity. For example, neighborhood walkability, which is increased with the presence of sidewalks and lower traffic volumes, is positively associated with youth MVPA.5–7 However, minority and low-income youths are more likely to face built environment barriers to active transportation, including lack of sidewalks,8 which might in turn reduce transportation self-efficacy (people’s beliefs in their ability to influence events that affect their lives)9 and subsequent active transportation participation among youths.

Perceived safety can also have an impact on self-confidence among youths, and parents’ support of youths to independently navigate neighborhood transportation systems. Just 53% of Black and 54% of Hispanic youths live in environments that are perceived to be safe, compared with 72% of White youths.1 Moreover, whereas three out of four youths report living close to a park area, park use is significantly lower in low- compared with high-income neighborhoods,1 again conveying inequitable opportunities for safe, accessible, and affordable active transportation for youths by race/ethnicity and income, resulting in downstream disparities in youth MPVA.

In this editorial, we propose a novel framework to discuss the relationship between youth transportation equity, transportation self-efficacy, and opportunities to promote youth physical activity. We also advocate enhanced transagency collaboration among public health, urban planning, transportation, and community recreation departments to reduce youth MVPA disparities. We frame this discussion by using a Public Health 3.0 approach, a model that aims to achieve health equity by addressing the social determinants of health through collaboration among health and nontraditional partners.10 Exploring this novel area of research presents an important opportunity to reduce gaps in youth health equity that influence long-term health among non-White and low-income populations in the United States.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

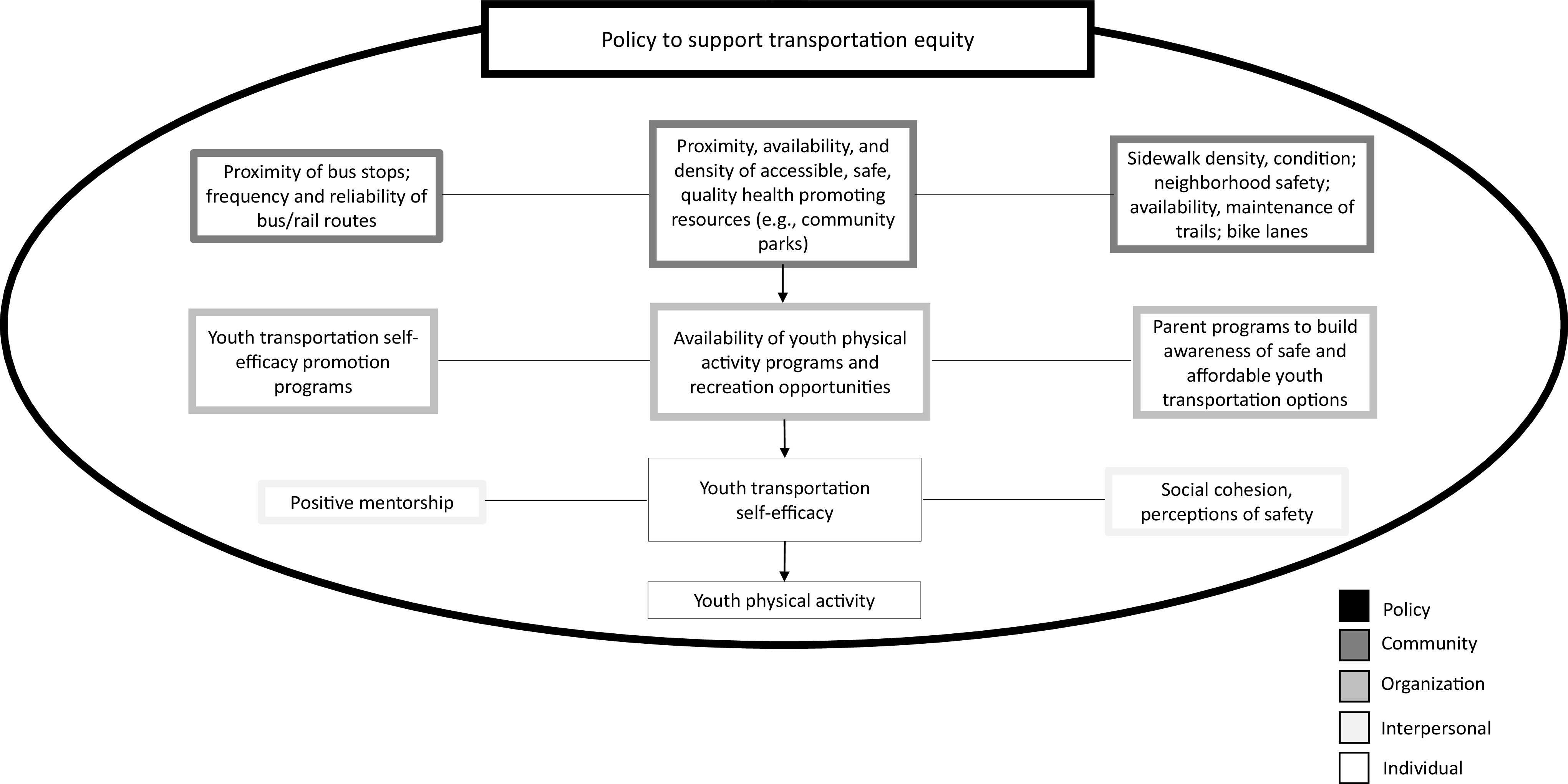

We propose a framework drawing from Public Health 3.0 to increase youths’ opportunities for active transportation and access to recreation spaces to reduce physical activity disparities (Figure 1). This framework presents a pathway connecting structural factors to youth transportation equity and physical activity behaviors that supports youths to independently navigate transportation systems, while increasing their self-efficacy to do so.8

FIGURE 1—

Conceptual Framework: Targeting Youth Transportation Equity and Self-Efficacy to Promote Youth Physical Activity

To begin, the proposed framework highlights the relationship between access to recreation spaces, transportation equity, and youth physical activity. First, as reflected in the proposed framework, we know that the proximity, availability, and density of accessible, safe, and quality health-promoting resources (such as community parks) are associated with youths’ utilization of community resources.11 Second, inequities exist in the accessibility of safe, active transportation, such as traffic volume, which predict disparities in youth pedestrian deaths across race/ethnicity and income. For example, Black children and low-income individuals are two times more likely to be killed while walking outside than White children and high-income individuals, respectively.2 However, land-use policies that limit pedestrian and cyclist exposure to traffic volume can reduce traffic injuries.12 Third, public transportation has been proposed as a mechanism to increase active transportation among youths, given that accessing public transportation often requires a 10- to 20-minute walk to a transit stop.13 Research has begun to explore the role of policy and urban planning to increase public transportation access as a means to promote youth physical activity, for example by supporting youths to independently navigate transportation to recreation spaces and activities.14

Our proposed framework also directly connects youth transportation self-efficacy to physical activity. Although targeting transportation infrastructure factors can promote youth MVPA, these measures do not address psychosocial factors, including the relationship between youth self-efficacy and transportation. Previous literature has established a strong association between children’s self-efficacy and active commuting to school.8 Also, a systematic review conducted by Rhodes et al.15 found an interaction between elements of social cognition, such as self-efficacy, and the built environment, including walkability, that led to higher levels of leisure-time physical activity. Carlson et al.16 similarly identified an association among self-efficacy, the built environment, and levels of physical activity. Self-efficacy also has frequently been explored as a psychosocial construct that can be leveraged to increase physical activity participation.8 However, the relationship between access to community recreation spaces, transportation self-efficacy, and physical activity has not been examined. As such, we include self-efficacy in our framework and argue that it is an important factor to consider in the pathway connecting structural factors to youth active transportation behaviors.

In addition, the proposed framework draws directly from a Public Health 3.0 approach.17 Both government and nongovernment public health actors have acknowledged the transportation sector as a nontraditional partner that can offer critical expertise for improving health equity.2,10 Public Health 3.0 regards nontraditional partnerships as integral to strengthening existing public health infrastructure.10 Therefore, to address upstream social drivers of youth physical activity disparities, we argue that this work must be done in partnership with transportation experts, urban planners, policymakers, community organizations, and local stakeholders.

Furthermore, our proposed framework connecting youths’ access to community recreation spaces, transportation self-efficacy, and physical activity draws from a socioecological context to inform future research in this area. Namely, multiple levels of societal influences, ranging from policy to interpersonal relationships, influence individual behavior18 and are needed to improve youth transportation self-efficacy and use of transportation systems. While community programs can be developed to promote youth transportation self-efficacy, policy and urban planning can improve transportation availability, accessibility, and safety for youth active and public transportation.2,8,16 These multiple levels of influence should be incorporated into designing and testing interventions that apply the proposed framework to planning, transportation, and community organization initiatives.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PLANNING AND POLICY

In alignment with our proposed framework to promote youth transportation self-efficacy and physical activity, applying the framework to developing and implementing planning initiatives similarly necessitates a Public Health 3.0 approach. For example, cross-sector collaboration is needed to create planning measures that promote equitable transportation access; implement measures that increase youth physical activity proximity, accessibility, and safety; and provide opportunities (such as with transportation initiatives) for youths to participate in community programs that provide safe, affordable, and engaging youth physical activity.8 Improving youths’ access to recreation spaces through active transportation initiatives (e.g., increasing access to well-maintained, well-lit sidewalks and bike lanes), or public transportation initiatives, such as providing free bus passes and connectivity between sidewalks and city buses, will facilitate more physical activity among youths.5 Expanding density of green and open spaces can also provide youths with increased motivation to navigate transportation systems to meet friends or attend programs to participate in physical activity recreation. Transagency collaboration in this sense is necessary to reduce physical activity disparities by promoting youth active transportation participation and access to health-promoting and engaging community spaces and programs.

We must also consider the larger context of policy to support youth transportation efficacy and related physical activity. Applications of our proposed framework can guide policy at national and state levels to facilitate greater prioritization in transportation use at local and community levels. For example, the federal government invests a percentage of funding into sidewalks, bike lanes, and trails.2 Funding can also be directed toward Public Health 3.0–style partnerships to support cross-sector collaboration to improve transportation accessibility, affordability, and use. Land use policies also play a role in improving youth transportation self-efficacy such as by supporting road safety programs, including Rails-to-Trails, Safe Routes to Schools, and Safe Routes to Parks initiatives.12,19 Policies can furthermore be enacted within schools that support greater active transportation, including bike racks at schools, traffic calming on school properties, and promoting biking and walking to school.

Given that public transportation availability does not equate to uptake and utilization, local youth community organizations can also foster youth transportation self-efficacy through evidence-based, stakeholder-driven programs to promote health equity. For example, partnerships among public health professionals, transportation specialists, and local youth organizations can improve youths’ and parents’ awareness of safe transportation options. Past interventions have targeted youth self-efficacy to increase participation in MVPA.2,16 Research also demonstrates a reciprocal relationship between environment and individual-level social cognitive constructs, such as walkability and the ability to overcome perceived barriers to physical activity.16 Therefore, coupling planning and policy changes with community-level programming will be critical for educating and motivating youths to use available transportation methods to increase their access to physical activity programs and recreation.

Consistent with the Public Health 3.0 “upgrade,” our framework also infers that a shift in current public health policy is necessary, away from spending targeting health care and toward supporting upstream structural drivers of health, mobilizing community stakeholders with actionable data, and including urban planning and transportation.9 Planning and policy measures therefore have potential to reduce physical activity inequities and associated disparities in chronic conditions by addressing youth transportation equity and self-efficacy and by engaging planning, transportation, and community organization partners to contribute expertise toward the common goal of improving youth public health.

CONCLUSION

Large inequities exist in MVPA between White and minority youths, and across socioeconomic status, resulting in health disparities tracking into adulthood. Current literature lacks exploration of youth transportation self-efficacy as a means to promote youths’ access to community recreation and opportunities for MVPA. However, transportation planning is increasingly linked to health outcomes, including reducing disparities in cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, air pollution–related illnesses, and traffic injuries, and should be considered an important avenue for population health promotion.12 Our proposed framework advocates transagency collaboration among nontraditional partners including public health, urban planning, transportation, and community recreation departments to address the intersection of transportation inequities, community recreation access, and youth physical activity. This framework presents an opportunity to reduce critical gaps in youth health equity and long-term health among minority populations, and propels us toward a Public Health 3.0 model for achieving a 21st-century public health infrastructure.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Physical Activity Plan Alliance. 2018. US report card on physical activity for children and youth. 2018. Available at: http://physicalactivityplan.org/projects/PA/2018/2018%20US%20Report%20Card%20Full%20Version_WEB.PDF?pdf=page-link. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- 2.Zimmerman S, Lieberman M, Kramer K, Sadler B. At the intersection of active transportation and equity. Safe Routes to School National Partnership. 2014. Available at: https://www.saferoutespartnership.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/at-the-intersection-of-active-transportation-and-equity.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- 3.Armstrong S, Wong C, Perrin E, Page S, Sibley L, Skinner A. Association of physical activity with income, race/ethnicity, and sex among adolescents and young adults in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(8):732–740. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konty KJ, Day SE, Larkin M, Thompson HR, D’Agostino EM. Physical fitness disparities among New York City public school youth using standardized methods, 2006–2017. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0227185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer MD, Elrahman OA. Transportation and Public Health: An Integrated Approach to Policy, Planning, and Implementation. Berkeley, CA: Elsevier; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira AF, Moreira C, Abreu S, Mota J, Santos R. Environmental determinants of physical activity in children: a systematic review. Arch Exerc Health Dis. 2014;4(2):254–261. doi: 10.5628/aehd.v4i2.158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rundle AG, Sheehan DM, Quinn JW et al. Using GPS data to study neighborhood walkability and physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(3):e65–e72. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu W, McKyer ELJ, Lee C, Ory MG, Goodson P, Wang S. Children’s active commuting to school: an interplay of self-efficacy, social economic disadvantage, and environmental characteristics. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Self-efficacy. In: Weiner IB, Craighead WE, editors. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2010. pp. 1–3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Public Health 3.0: a call to action to create a 21st century public health infrastructure. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/Public-Health-3.0-White-Paper.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kaczynski AT, Besenyi GM, Stanis SAW et al. Are park proximity and park features related to park use and park-based physical activity among adults? Variations by multiple socio-demographic characteristics. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0146-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholas W, Vidyanti I, Caesar E, Maizlish N. Routine assessment of health impacts of local transportation plans: a case study from the City of Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):490–496. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durand CP, Pettee Gabriel KK, Hoelscher DM, Kohl HW. Transit use by children and adolescents: an overlooked source of and opportunity for physical activity? J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(8):861–866. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palm M, Farber S. The role of public transit in school choice and after-school activity participation among Toronto high school students. Travel Behav Soc. 2020;19:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tbs.2020.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodes RE, Saelens BE, Sauvage-Mar C. Understanding physical activity through interactions between the built environment and social cognition: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2018;48(8):1893–1912. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson JA, Sallis JF, Kerr J et al. Built environment characteristics and parent active transportation are associated with active travel to school in youth age 12–15. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(22):1634–1639. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeSalvo KB, O’Carroll PW, Koo D, Auerbach JM, Monroe JA. Public Health 3.0: time for an upgrade. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):621–622. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological Models of Human Development. 2nd ed. Vol 3. Berkeley, CA: Elsevier; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safe Routes Partnership. Active Paths for Equity and Health. Available at: https://www.saferoutespartnership.org. Accessed December 16, 2020.