“Predictable surprises” should be anticipated and can be better institutionalized in hospital response systems for crises.1 An opportunity exists to implement strategies for hospital-based disaster management by explicitly integrating equity principles and expertise as central components of the Hospital Incident Command System (HICS).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitals and health care systems have activated HICS to coordinate hospital-wide disaster responses. HICS are a structural tool used to clarify roles, responsibilities, authority, and accountability to streamline decisions and action during complex crises. In the late 1980s, the hospital emergency incident command system (now HICS) was developed to align with the National Interagency Incident Management System, the federal plan for improving coordination among agencies in a broad range of large-scale emergencies.2

As HICS have been deployed over recent decades, we have deepened our understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of their structure for addressing the needs of diverse populations. Recurrent experiences with large-scale disasters, including the COVID-19 pandemic and Hurricanes Katrina, Maria, Harvey, and Sandy, have underscored the ways in which health care responses, emergency preparedness, and broader social determinants of health lead to preventable morbidity and mortality in marginalized communities.3

Here we share the case for embedding an equity element in HICS, our institutional experiences in operationalizing equity, and our recommendation for a structural change in the national HICS guidelines: including a defined equity officer (EO) and subject matter experts in health care equity to ensure that actions are taken to improve outcomes for diverse groups during public health emergencies or disasters. Although our focus is on HICS, these concepts can and should be more broadly applied in all emergency support functions. Emergency support functions are groupings of governmental and private-sector capabilities into an organizational structure to provide support, resources, and services that are needed to save lives, protect property and the environment; restore essential services and critical infrastructure; and help victims and communities return to normal after domestic incidents.

EMBEDDING AN EQUITY RESPONSE WITHIN THE HICS INFRASTRUCTURE

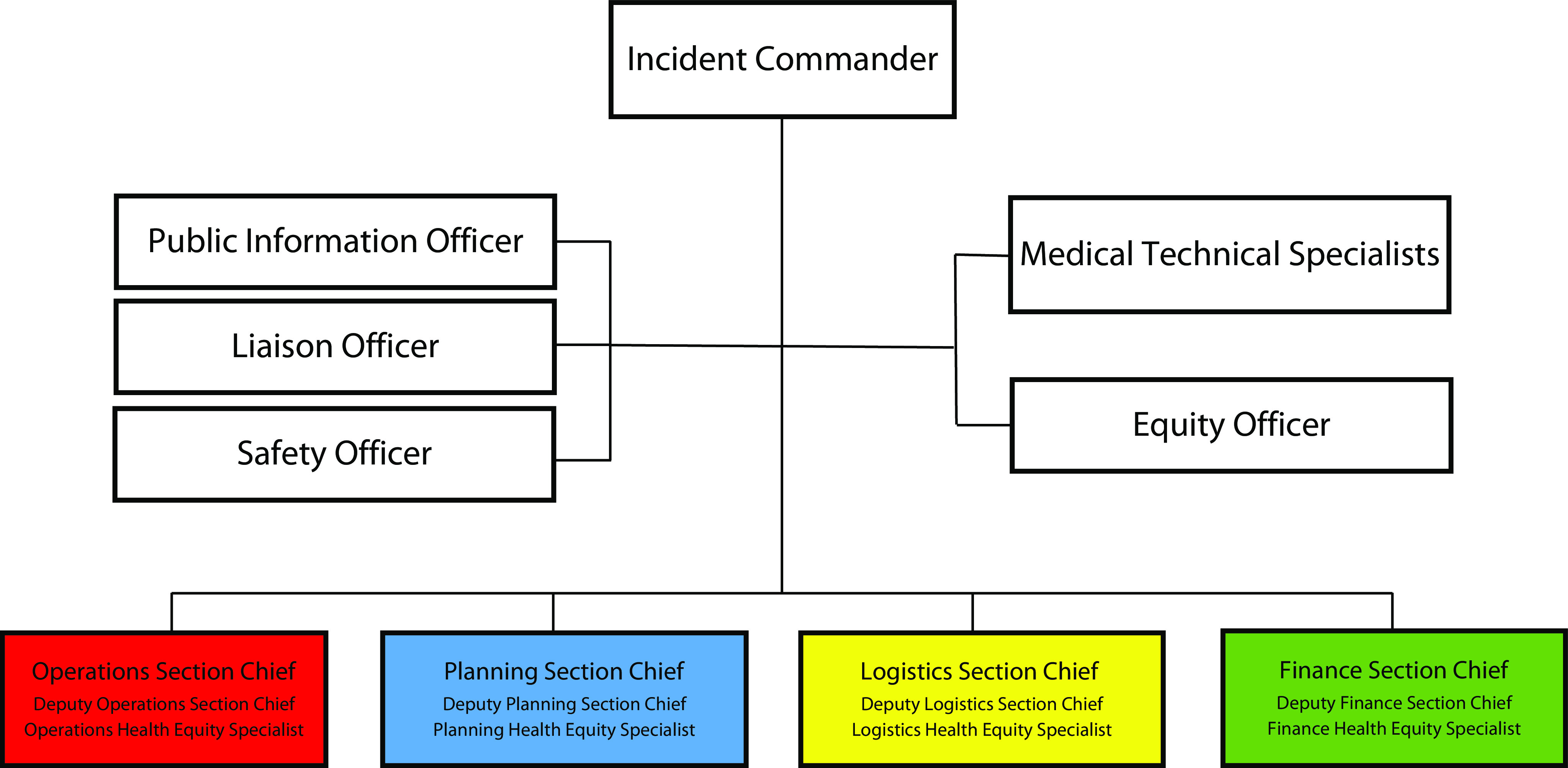

The key principles of HICS are a unified command, a clear organizational structure, and an incident action plan guided by objectives. The incident commander leads a team of section chiefs in charge of operations, planning, logistics, and finance. Several command staff members also report to the incident commander: a public information officer, a safety officer, a liaison officer, and medical technical specialists. However, HICS guidance as currently written does not explicitly specify an EO role or list equity as a responsibility or operational priority in hospital crisis response. Ideally, the incident commander would embed equity principles and objectives implicitly in HICS planning.

Recent events illustrate the need to explicitly name roles and responsibilities to address health equity within the HICS structure. The absence of equity as an emergency management principle in responses to COVID-19 has resulted in a slow and incomplete hospital response to the disproportionate mortality and morbidity in several historically marginalized populations.4 For example, hospitals have access to detailed information on the demographic composition of their inpatient populations, the ability to screen patients for social needs, and the opportunity to conduct coordinated community outreach to address the needs of communities of color through HICS infrastructure. However, the extent to which communities of color, particularly African American, Latinx, and Native American groups, were disproportionately dying from COVID-19 did not become clear until weeks into the pandemic.5

Additional issues, including disparate access to hospital-based viral testing and access to emerging therapies for treating coronavirus, have not been evenly reported or monitored. The response to rising food insecurity reported during the pandemic speaks to the absence of health-related social needs planning in the HICS pandemic response. Importantly, scarce resource allocation frameworks, called crisis standards of care, have incompletely incorporated the values of marginalized communities.6 As we have observed over the past year, crisis standards of care frameworks have improved—with greater diversity, equity, and inclusion expertise involvement—but demand long-term involvement and change to mitigate inequities. One recent example is the Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s revision of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, which includes “appropriate modifications for people with disabilities and modification to mitigate the disproportionate impact of chronic kidney disease [and is to be used] to characterize patients’ prognosis for hospital survival.”7

Each of these deficits reflects structural racism and the need for long-term institutional infrastructure building to address deeply entrenched historic inequities.8 However, the need for structural change does not obviate the need for hospitals to develop institutional responses to meet acute crisis needs of African Americans and other groups at risk for inadequate care and outreach. Indeed, one expression of structural racism is the failure to assign responsibility and procure the expertise needed to meet acute needs during times of crisis, even as longer-term planning and structural changes progress. HICSs are designed to ensure a streamlined, effective response, but the current pandemic has demonstrated that not all needs of all populations have been met. There is a need to integrate explicit responsibilities for efforts to strengthen data collection and monitoring, to build liaisons for community engagement, and to embed activities that address equity in each phase of a disaster, and mitigation, preparation, response, and recovery are needed to ensure that the needs of marginalized groups are equitably addressed.

OUR INSTITUTIONAL EXPERIENCE EMBEDDING EQUITY

Approximately two months into the activation of HICS activities within our hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic, at the direction of our corporate incident command center, our hospital established a diversity, equity, and community health response team that was chaired and docked within our HICS. As a part of the response, our team established several work streams to augment and accomplish core functions of the HICS response, including employee equity, health care access, communications, public policy and advocacy, and data and monitoring.

Through these work streams, our team embedded several activities in our hospital response to ensure that hospital and corporate entity resources were used to meet the needs of historically marginalized groups, including patients, employees, and local communities. These activities included ensuring adequate protective personal equipment for nonclinical staff, leading efforts to provide community-based virus testing, and engaging in community outreach to address food insecurity as a social determinant of health.9 Future work will add further work streams to augment recovery and reimagining as our hospital reopens to provide emergent clinical care that could not be provided during the crisis response.

OUR AFTER-ACTION REVIEW DEFINED THE GAP

A critical learning process in emergency management is the after-action review. An after-action review is a structured process developed by the US Army to identify strengths and weaknesses in event response.10 This concept has been adapted as a critical step after public health emergencies to gather information on quantitative and qualitative issues to improve preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery for future incidents.11 Our institution has conducted several after-action reviews within the past decade after local events including the Boston Marathon bombings and an active shooter incident in our hospital.12–14 We have also facilitated reviews in the wake of other large-scale events such as the urban terror attacks in Paris and Brussels.15

Since our initial patient surge in Boston, Massachusetts, in April 2020 (and given the concern for future surges), we have conducted several debriefings with more than 150 staff members across an academic medical center and community hospital within our larger multihospital health care system.

The most frequently mentioned topic in our review was equity. Many comments highlighted the positive effects of the existing work streams and our ongoing efforts. Key areas identified were to embed equity experts in the HICS, display and use COVID-19 dashboard data that systematically stratify demographic characteristics, empower equity experts to lead within and beyond the organization, aggressively communicate initiatives, ensure that all materials are inclusive of various reading levels and languages, and actively encourage engagement by frontline staff whose voices may have previously been marginalized.

However, many of those involved in the process acknowledged that we are at the beginning and have much work to do to ensure that equity is a core function of our response during the COVID pandemic and in future disasters. A consensus research agenda will be critical to understanding the effects of future interventions designed to mitigate structural racism during disasters.16 On the basis of our observations, we recommend a structural change to the national HICS guidelines: including an EO and embedded health equity specialists within each section.

THE HICS EQUITY OFFICER AND THE HEALTH EQUITY RESPONSE

Defining an EO as a mandatory, core member of the command and general staff is a first step in mitigating inequities. The EO would directly report to the incident commander as a member of the command staff. The EO would have authority to command the resources needed to accurately identify threats to the well-being of marginalized groups and take steps to ensure that hospital activities and plans during crisis responses operate fairly and equitably to meet the needs of hospital employees, patients, and surrounding communities. The EO would advance an equity ethics in crisis management principle to ensure that the needs of the few and vulnerable are in balance with the needs of the many and powerful, such that decisions to distribute scarce resources (e.g., medications, funding for interpreters) are made to benefit marginalized populations, even if such resources are not required to respond to the crisis needs of majority populations.

Furthermore, medical technical specialists with health care equity expertise embedded within each HICS section would provide real-time insights for rapid cycle innovations to mitigate disproportionate impacts on vulnerable groups. Just as each member of the HICS team has a discrete role and responsibility, the EO and health equity specialists should be involved in all critical decisions and embed as core, trusted, essential members.

Figure 1 shows a proposed structure for the role of the EO and health equity specialists within the HICS infrastructure. Together with the liaison officer, the EO would coordinate with community-based, municipal, state, or other agencies to establish partnerships and coalitions for addressing underlying public health and social service barriers to crisis response. A successful response would ensure that the needs of marginalized populations are centrally integrated into problem definition, decision-making, and processes and outcomes of HICS activities (e.g., operations, planning, logistics, finance).

FIGURE 1—

Proposed Hospital Incident Command System Organizational Chart

Essential work of the EO and health equity specialists would include the following, at minimum17:

Directing data collection for planning and management consistent with 2011 US Department of Health and Human Services guidance on assessing race, ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation and gender identity, and disability;

Ensuring use of culturally appropriate communication channels (digital and nondigital), appropriate use of languages and codes (including closed captioning and Braille), and attention to literacy levels (including infographics) for disseminating crisis information;

Planning for adequate access to essential medications and equipment (e.g., insulin, pain medications, dialysis machines, and ventilators) for use within the hospital and for distribution in community settings as appropriate;

Coordinating with and supporting trusted community agencies to provide social services;

Coordinating and working with local public health organizations; and

Ensuring equity in research participation.

Not only should EOs work within their organizations, but they should identify and advocate for similar leadership opportunities and roles at fellow public health agencies. Successful strategies used during HICS, such as developing metrics of equitable processes of care, should be tested and incorporated in standard hospital operations.18 For example, our HICS experience has led to greater institutional use of hospital equity data monitoring as an institutional practice, and we have now applied this practice to monitoring equity in access to COVID-19 vaccination among our hospital staff employees.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the response to COVID-19 is still unfolding, the lessons of this pandemic underscore the experience of several prior crises in recent US history in which communities of color, populations of low socioeconomic status, and other groups suffer disparate impacts. Embedding an EO and health equity specialists within HICS is an important next step to address hospital-based contributions to institutional racism that has led to disproportionate illness and loss of life in marginalized communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work to implement equity as an essential element of HICS should be urgently shared now and continuously evaluated and refined through each phase of the pandemic. Deliberate, integrated changes in our crisis management structure are an essential step to mitigate future preventable deaths in our most vulnerable populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Eric Goralnick received funding from the Henry M. Jackson Foundation, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Richard Nesson Fellowship, the Gillian Reny Stepping Strong Center for Trauma Innovation, and CRICO. Cheryl R. Clark received funding from the National Institutes of Health and IBM Watson Health.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

See also the COVID-19/Public Health Preparedness and Response section, pp. 842–875.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bazerman M, Watkins M. Predictable Surprises. Brighton, MA: Harvard Business Review Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.California Emergency Medical Services Authority. Hospital Incident Command System guidebook. Available at: https://emsa.ca.gov/disaster-medical-services-division-hospital-incident-command-system. Accessed January 4, 2021.

- 3.Howell J, Inequality R. Hurricane Katrina, the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, and the aftermath of disaster. Soc Forces. 2019;98(2):1–3. doi: 10.1093/sf/soz083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleveland Manchanda E, Couillard C, Sivashanker K. Inequity in crisis standards of care. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):e16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2011359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkowitz SA, Cené C, Chatterjee A. Covid-19 and health equity—time to think big. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(12):e76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Crisis standards of care planning guidance for the COVID-19 pandemic. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/doc/crisis-standards-of-care-planning-guidance-for-the-covid-19-pandemic/download. Accessed January 4, 2021.

- 8.Williams DR, Cooper LA. COVID-19 and health equity—a new kind of “herd immunity. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2478. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark CR, Goralnick E, Eappen S. Managing complexity: hospital incident command systems, COVID 19, and health equity. 2020 [video Webinar]. Available at: https://ihi.webex.com/recordingservice/sites/ihi/recording/73ddaeb60f1a4bf1b6e547ef988ab389/playback. Accessed March 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison JE, Meliza LL. Foundations of the After Action Review Process. Alexandria, VA: Institute for Defense Analyses; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies R, Vaughan E, Fraser G, Cook R, Ciotti M, Suk J. Enhancing reporting of after action reviews of public health emergencies to strengthen preparedness: a literature review and methodology appraisal. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;13(3):618–625. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goralnick E, Halpern P, Loo S et al. Leadership during the Boston Marathon bombings: a qualitative after-action review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2015;9(5):489–495. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gates JD, Arabian S, Biddinger P et al. The initial response to the Boston Marathon bombing: lessons learned to prepare for the next disaster. Ann Surg. 2014;260(6):960–966. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goralnick E, Zinner MJ, Ashley SW. A death in the family: lessons from a tragedy. Ann Surg. 2016;263(2):230–231. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goralnick E, Van Trimpont F, Carli P. Preparing for the next terrorism attack: lessons from Paris, Brussels, and Boston. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(5):419–420. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berwick DM, Shine K. Enhancing private sector health system preparedness for 21st-century health threats: foundational principles from a National Academies initiative. JAMA. 2020;323(12):1133–1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Services. Implementation guidance on data collection standard for race, ethnicity, sex, primary language, and disability status. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/hhs-implementation-guidance-data-collection-standards-race-ethnicity-sex-primary-language-and-disability-status. Accessed January 4, 2021.

- 18.American Hospital Association. Health equity snapshot: a toolkit for action. Available at: https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/12/ifdhe_snapshot_survey_FINAL.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2021.