The COVID-19 public health crisis has led to a historic increase in food insecurity throughout the United States. Long lines of people—some on foot, some in cars—waiting to receive food assistance have made headlines since March 2020. Photographs of these lines, reminiscent of photographs of the bread lines of the Great Depression, have highlighted the need for stronger coordination between government and the charitable food system to adequately address food insecurity.

In 2020, Feeding America conservatively projected a 36% growth in national food insecurity rates: from 11.5% in 2018 to 15.6%.1,2 The proportion of disadvantaged adults receiving charitable food rose 61%: from 9.0% in December 2019 to 14.5% in June 2020.3 To address this increased need, the charitable food assistance system has quickly adapted. However, the charitable system alone cannot meet this staggering hunger crisis. Federal and state government assistance must be expanded to support the charitable food system, as the repercussions of the pandemic are likely to continue for years to come.

AN OVERBURDENED CHARITABLE FOOD SYSTEM

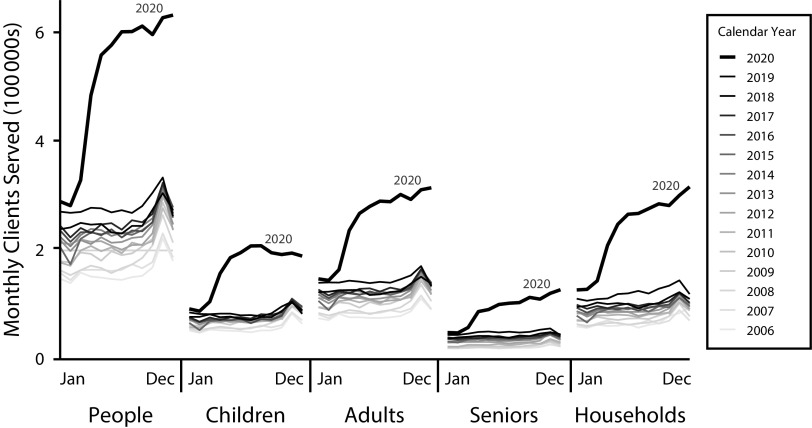

In June 2020, Massachusetts had the highest unemployment rate in the country at 17.4%,4 driving COVID-19 food insecurity rate projections to increase by 59%: from 8.9% in 2018 to 14.2% in 2020.1,2 This increase is the highest in the nation. According to reports from The Greater Boston Food Bank’s (GBFB’s) network of 600 food distribution partners across Eastern Massachusetts, the number of people receiving food from GBFB’s food pantry network doubled from 280 000 in May 2019 to 560 000 in May 2020 and remained at similarly high levels throughout 2020 (Figure 1). The actions taken by GBFB are representative of how the charitable food system has scaled rapidly to address the increased demand for food assistance. GBFB has had to increase food acquisition by 55%, primarily through increasing privately funded food purchases by approximately 130% for March through December 2020 (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Monthly Clients Served by The Greater Boston Food Bank’s (GBFB) Food Pantry Network: Boston, MA, 2006–2020

Note. Of 334 GBFB partner food pantries, 99% submitted data for December 2020. November spikes are attributable to increased pantry use around Thanksgiving. These are not unique counts because they do not take into account that some households attend multiple pantries each month.

GBFB distributed this influx of food by relying on a robust and resilient food pantry network and partnerships with our state agencies. GBFB’s long-term support of the network through annual infrastructure grants for items such as refrigerators and trucks prepared it to receive a sudden increase in food. From March through December 2020, 62% of the pantries ordered more food from GBFB than they had during the same period in the previous year, and 95% of the network remained open at any given time during the pandemic (GBFB unpublished administrative data). As the pandemic evolved, GBFB increased funding to food pantries and bolstered support of high-need communities by developing new partnerships with organizations that served as pop-up distribution centers. Through its network, GBFB distributed 94 million pounds of food from March through December 2020, a 58% increase compared with the same period in 2019 (Figure A). Fruits and vegetables continued to make up more than a third of food distributed (Figure A).

Charitable organizations have used their networks creatively to respond to the pandemic. However, these adaptations are unsustainable without systemic policy changes: 75% of GBFB’s partner food pantries anticipate food supply challenges, 43% report limited physical space, and 36% report not enough staff and volunteers as their key concern (Massachusetts Food Security Task Force, food pantry and meal provider survey, November 2020). The substantial burden placed on the charitable food system must be mitigated by long-term government assistance to food banks and individuals. We can meet the hunger crisis only if our charitable, federal, and state food systems work together.

FEDERAL AND STATE SUPPORT

Since 1983, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has provided federal assistance to food banks by providing surplus commodities through the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP). TEFAP has expanded since 2019, partly as a result of the USDA’s increased purchase of food directly from US farmers—designed to address decreased exports attributable to trade wars—and, as a result, food donations are expected to drop by 50% in 2021. The federal government also increased funding for TEFAP through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Family First Coronavirus Response Act. Additionally, the USDA created the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program, which contracts regional vendors to provide food to individuals in need. However, some of these pandemic-specific programs were only temporarily extended as part of the relief package that was passed in December 2020.

States also support charitable food assistance. The Massachusetts governor, Charlie Baker, pulled together the Food Security Task Force, composed of state agencies and hunger relief organizations, which prioritized food assistance in the state’s COVID-19 response and helped focus the state’s collective response. The Salvation Army, in partnership with the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency, created nonperishable food boxes that were distributed to hot spot areas of high need from May through August 2020. The state also led the way in rolling out the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program, which came out of the CARES Act. The Massachusetts Emergency Food Assistance Program, a state economic stimulus program created in 1995 to support food banks in Massachusetts with funding to purchase food, was provided a significant increase, from $20 million to $30 million, in the fiscal year 2021 state budget. Similar programs exist in Pennsylvania, Ohio, New Jersey, and New York.

THE GOVERNMENT’S ROLE IN REDUCING HUNGER

As these temporary, acute pandemic-response programs end, perilous food insecurity rates continue in Massachusetts and throughout the country. Following previous recessions, elevated food insecurity rates typically persisted for multiple years; after the Great Recession ended, it took nine years for food insecurity to return to prerecession levels.5 Long-term federal and state support is essential to support household food security for the duration of an extended economic recovery.

Although the charitable food system is vital to addressing food insecurity in the United States, it is only one component. For every meal provided through food banks, nine are provided through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).6 Although the December 2020 stimulus package included temporary boosts for SNAP and TEFAP and improved guidance for P-EBT, this is just the first step in sustainably addressing food insecurity. President Biden’s January 2020 executive orders to increase P-EBT by 15%, increase SNAP benefits for the lowest-income households, and revise the Thrifty Food Plan, on which SNAP benefits are calculated, are stronger steps in the right direction. The Biden–Harris administration has also called on Congress to extend the 15% SNAP benefit increase and invest another $4 billion in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

As the charitable food system continues to experience an increased demand for food, the increased cost of food, and supply chain disruptions, it cannot guarantee a consistent food supply without continued government support. Throughout the economic recovery, the federal government must increase funding for programs that support the charitable food system, like SNAP, WIC, P-EBT, school meals, and TEFAP. Greater transparency and accountability in new USDA programs will allow charitable food providers to adequately plan for program changes and disruptions. States should create food-purchasing programs, similar to the Massachusetts Emergency Food Assistance Program, and support state emergency management agencies to create large-scale emergency food programs, such as the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency food box program.

Many people facing food insecurity in the United States are unable to access federal safety net programs because of income level, immigration status, work requirements, or other disqualifying factors. Even before the pandemic, it was not just those in poverty who were experiencing food insecurity: 32% of the nation’s food insecure population was ineligible for federal food assistance because they had a household income above the eligibility income threshold.2 Now, more than ever, these eligibility barriers need to be reevaluated and increased to successfully reduce hunger in the United States.

Further, long-term policy initiatives are necessary to meet Americans’ food needs and offset the pandemic-induced unsustainable reliance on food banks as emergency programs sunset. Systemic policy solutions include increasing the minimum wage to $15 an hour nationwide, expanding eligibility and permanently increasing benefits for SNAP and WIC, building on the existing Community Eligibility Program to create a nationwide universal school meals program, and installing P-EBT as a permanent program to allow low-income students to access food during school breaks to supplement overburdened charitable food organizations.

Food insecurity was an emergency long before the COVID-19 crisis. The United States has the potential to transform its hunger crisis response into a sustainable solution if it uses the multifaceted approach of addressing the wealth gap while boosting and sustaining federal nutrition programs to systematically address food insecurity in the United States.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

L. Fiechtner is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant K23HD090222).

We thank Ned Armsby, Chris Farrand, Dan O’Neill, and Julianne White for providing information on food bank and government programs. We thank Molly Kepner and Carol Tienken for providing feedback on the editorial.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feeding America. Map the meal gap 2020: a report on county and congressional district food insecurity and county food cost in the United States in 2018. 2020. Available at: https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/Map%20the%20Meal%20Gap%202020%20Combined%20Modules.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2021.

- 2.Feeding America. The impact of coronavirus on food insecurity. October 30, 2020. Available at: https://www.feedingamerica.org/research/coronavirus-hunger-research. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 3.Ziliak JP. Food hardship during the COVID‐19 pandemic and Great Recession. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2020;43(1):132–152. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York had highest unemployment rates in June 2020. July 22, 2020. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/massachusetts-new-jersey-and-new-york-had-highest-unemployment-rates-in-june-2020.htm. Accessed November 12, 2020.

- 5.Coleman-Jensen A. Food insecurity in US households in 2018 is down from 2017, continuing trend and returning to pre-recession. 2007. level. October 3, 2019. Available at: https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2019/10/03/food-insecurity-us-households-2018-down-2017-continuing-trend-and-returning. Accessed December 22, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leone K. Feeding America statement on House introduction of HEROES Act. May 12, 2020. Available at: https://www.feedingamerica.org/about-us/press-room/feeding-america-statement-house-introduction-heroes-act-1. Accessed December 22, 2020.