Abstract

Failed by mainstream medical institutions, 1970s revolutionaries of color sought to take health care into their own hands. A lesser-known phenomenon was their use of acupuncture. In 1970, an alliance of Black, Latinx, and White members at Lincoln Detox, a drug treatment program in the South Bronx area of New York City, learned of acupuncture as an alternative to methadone. In Oakland, California, Tolbert Small, MD, used acupuncture for pain management following his exposure to the practice as part of a 1972 Black Panther Party delegation to China. Unaware of one another then, the Lincoln team and Small were similarly driven to “serve the people, body and soul.” They enacted “toolkit care,”—self-assembled, essential community care—in response to dire situations such as the intensifying drug crisis. These stories challenge the traditional American history of acupuncture and contribute innovations to and far beyond the addiction field by presenting a holistic model of prevention and care. They advance a nuanced definition of integrative medicine as one that combines medical and social practices, and their legacies are currently carried out by thousands of health care practitioners globally.

At an opioid recovery center in New Hampshire, 10 people sat in the lounge, each with five needles sticking out of both ears. They were all White and identified as making low income.1 This was the distinctive ear acupuncture treatment of the National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA), used for substance use, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and more.2 I asked if they believed in acupuncture, which they were receiving for free. They unanimously agreed—it made a difference. One man elaborated, “We don’t know what medicine is anymore. Whatever works, works.”3

FIGURE 1—

Tolbert Small, Back Right, and David Levinson, Third From Left, With Barefoot Doctors in Yenan, China, March 22, 1972

Source. Tolbert and Anola Small Papers, the archives of the Small family, which are in the early stages of being organized by the family and the author. Printed with permission.

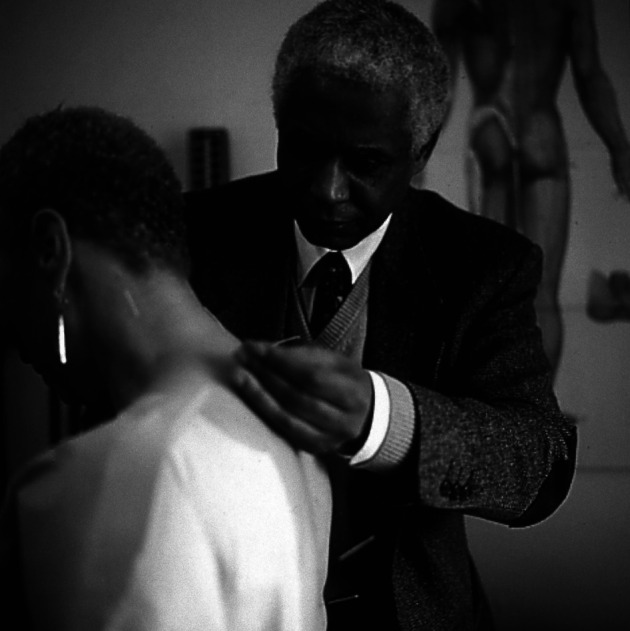

FIGURE 2—

Tolbert Small Treating a Patient With Acupuncture for Back Pain in the Upstairs Room of the Harriet Tubman Medical Office in Oakland, CA

Note. This room was dedicated to acupuncture, 1993.

Source. Tolbert and Anola Small Papers, the archives of the Small family, which are in the early stages of being organized by the family and the author. Printed with permission.

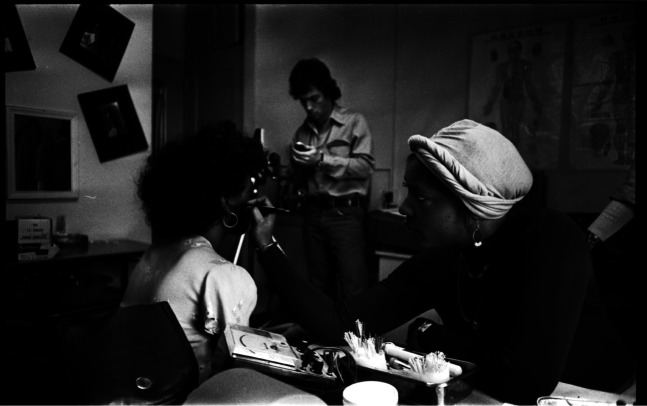

FIGURE 3—

Unidentified Lincoln Detox Member Treating a Patient Using Ear Acupuncture

Note. Photo is a still from Mia Donovan’s EyeSteelFilm documentary, Dope is Death, 1973.

Source. Carlos Ortiz, courtesy of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College. Printed with permission.

According to a 2012 National Institutes of Health report on the use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAM), 33.2% of the adult US population, especially non-Hispanic Whites with higher incomes, had tried CAM practices in the 12 months prior.4 With biomedicine as a cause of the opioid epidemic, it is unsurprising that patients would look elsewhere, yet the crisis is likely shifting the CAM user demographic. Furthermore, in stark contrast to the 2012 report, the NADA protocol traces back to 1970s activists of color—to those connected with the Black Panther Party (BPP) or the Young Lords, two revolutionary groups advocating for the self-determination of poor and oppressed communities, the former consisting largely of Black activists and the latter of Latinx radicals.5 The revolutionaries sought to provide for the holistic needs of marginalized populations, such as health care access. This history includes the use of acupuncture.

In New York City, the BPP, Young Lords, and other revolutionaries founded Lincoln Detox, a drug treatment program, at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx. In 1970, Mutulu Shakur, an informal affiliate of the BPP, was introduced to acupuncture and suggested it to Lincoln as an alternative to methadone.6 Lincoln eventually became the site for the development of the NADA protocol, now used globally. Yet, this was not the only instance in which 1970s revolutionaries used acupuncture.7 In California, Tolbert Small served as the BPP’s medical director between 1970 and 1974. He visited China as part of a BPP delegation in 1972 and witnessed acupuncture for the first time.8 Fascinated, Small incorporated the practice into his medical toolkit upon returning home. He has since treated thousands with acupuncture for pain management, often in lieu of prescribing drugs.

These two stories have received sparse attention but offer significant contributions to the history and policy of public health.9 They challenge the traditional narrative of the arrival of acupuncture in the United States perpetuated by American Chinese medical schools and biomedical institutions, by preceding or running in parallel with New York Times reporter James Reston’s 1971 article on his acupuncture treatment in China.10 Furthermore, they argue for a nuanced definition of integrative medicine as one that combines medical and social practices.

Acupuncture in the hands of the revolutionaries carried sociopolitical meanings and motivations. They employed “toolkit care” as their logic of survival.11 Based on the notions of health care for the people by the people, their approaches embodied and defined toolkit care—the endeavor for community self-efficiency and self-empowerment through self-assembled, mobile means.12 It merged the concepts of do-it-yourself and first aid, connoting a care that responded to emergencies, including dire health care needs. In particular, the revolutionaries’ use of acupuncture as part of their toolkit explicitly addressed the intensifying crisis and criminalization of drug use in communities of color. With addiction seen largely outside the purview of medicine and public health during the War on Drugs (legacies of which have lasted well into the 21st century), these revolutionaries took health care into their own hands, using acupuncture as prevention and care for addiction.

Their toolkit care was born not necessarily out of desperation but rather a desire to reclaim authority and the right to heal. This practical care was built of essential skills the revolutionaries metaphorically and physically carried as they worked to meet the communities’ local needs and “serve the people, body and soul.”13 Acupuncture fit the revolutionaries’ toolkits; it was economical, accessible, responded to the drug crisis, and was understood as part of Maoist ideology, which significantly influenced the revolutionaries, especially in health care delivery.14

Expanding upon sociologist Alondra Nelson’s analysis of the BPP’s health activism, the employment of integrative medicine demonstrated the Black and broader revolutionary movement’s commitment to laying claim to the right to health equality.15 As AJPH Editor-in-Chief Alfredo Morabia has noted, dominant narratives of the BPP’s violent state confrontations have obfuscated the party’s broader community service legacies.16 These histories of Small and Lincoln fill in a fuller picture of not only the BPP, but also the 1970s revolutionaries of color and offer a detailed lineage of their influence on the wider American and global population from then to now.

THE 1972 CHINA LESSON

In August 1963, Mao Zedong, chairman of the Chinese government, issued a global call to support the Black struggle against oppression by the US government. Disseminated by the Chinese Communist Party’s The People’s Daily, Mao’s statement solidified many revolutionary groups’ commitment, such as the BPP’s, toward Maoist ideology. Founded in 1966, the BPP funded much of their arms purchases by selling the “Little Red Book,” a collection of Mao’s writings. BPP founders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale lifted the party’s signature term, “serving the people,” directly from the red book.17 Maoist ideology provided them guidance on the means for societal transformation; in particular, the barefoot doctor movement was a key influence.

Laypersons with basic Western and Chinese medical training, barefoot doctors carried “medical kits,” including acupuncture, into rural communities lacking medical care, resembling the health care deserts in many American communities of color.18 This movement informed the BPP’s health care praxis and toolkit care. With a 10-point platform, including the demand for “completely free health care for all black and oppressed people,” the BPP established a national network of People’s Free Medical Centers, which spanned 13 major cities, from Los Angeles to New York City.19 At the George Jackson Medical Clinic, the headquarters’ clinic in Oakland, California, physicians and laypersons worked as “24-hour revolutionaries” to provide medical care.20

Tolbert Small was the director of the George Jackson Medical Clinic during its height in 1970 through 1974. Born in Coldwater, Mississippi in 1942, Small and his family moved to Detroit, Michigan when he was a few months old. While attending the University of Detroit, he cofounded the student chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Seeking to alleviate the health care needs of his community, Small graduated from the Wayne State School of Medicine in 1968 on a Sloan Foundation medical scholarship.21 His residency in internal medicine brought him to Oakland, where he approached the BPP in 1970. Although he did not join, believing he would be more effective as a nonmember, he provided medical services pro bono and served as the BPP’s physician. He visited jails and prisons, treating prominent BPP activists and affiliates such as George Jackson and Angela Davis. Small also codirected the national BPP Sickle Cell Anemia Project, which promoted education and screening among Black communities.22 This work pressured Richard Nixon’s administration to fund research to eradicate sickle cell anemia.23

In March 1972, Small traveled to China with a BPP delegation organized by Newton, who visited China in November 1971 and asked if he could send a group the following spring.24 Granted permission by the Chinese Communist Party, Newton selected 20 participants, including BPP members, other activists, social workers, health professionals, teachers, and children. According to the BPP newspaper, the group “had come from their different walks of life to work and live together under the tutelage of the Black Panther Party.”25 Small was the only physician. The delegates visited factories, schools, and medical facilities over the course of seven weeks. David Levinson, then 19 years old and a White BPP member, recalled meeting “many revolutionary people … and there was much about that vision, much about that commitment, and heartfelt desire that we connected to.” The delegates believed they were witnessing their ideologies actualized “on a mass, grand scale.”26

At urban hospitals and rural clinics, the group was introduced to acupuncture. At hospitals, they watched acupuncture anesthesia used for surgeries such as a thyroidectomy. In the countryside, they met barefoot doctors who carried aspirin alongside “one silver needle and a bunch of herbs” (yigen yinzhen, yiba caoyao) in their medical toolkit.27 In Small’s audio recordings of the trip, the tour guides emphasized “the seamlessness of integration” of Chinese with Western medicine, referring to the national “East–West Medicine Integration” (zhongxiyi jiehe) policies. The guides suggested the delegates “integrat[e] traditional Black medicine with modern medicine to serve people better.”28 This encouraged the revolutionaries’ self-assembled toolkit care, as “these were the tools and techniques that were available and easily disseminated without having to rely on Western technology or ideas of medicine.”29

Intrigued, delegates bought acupuncture needles and tried needling themselves. “The Chinese came to us and diplomatically said that they were enthused by our interest but warned that it could be dangerous if we didn’t know what we were doing,” Levinson recounts.30 The officials then organized acupuncture lectures, led by a certain “Dr Wu” in Shanghai. “It was spectacular,” Small recalled, “I had to learn more . . . I was inspired by how one million barefoot doctors brought medicine into the communities.”31 Upon returning home, Small taught himself acupuncture by trying points on himself, referring to an English-translated Chinese medical text.32

Small was interested in biomedical understandings of acupuncture, although he was not opposed to “other ways of explaining.” Small recalled, “the meridian system is one way of explaining acupuncture, but I wanted to explain it in familiar terms.” He subscribed to translated Chinese medical journals and published two articles in the American Journal of Acupuncture in 1974: “The Neurophysiological Basis for Acupuncture” and “Acupuncture Anesthesia: A Review.” He specifically paid attention to acupuncture’s pain relief potential and described the practice as a mechanism of stimulating endorphin release and blocking pain transmission. Later, he presented a talk entitled “Traditions of Healing Acupuncture” to hospitals and community centers. “I had this business card that I got in Mexico that said, ‘Tolbert Small, Research Acupuncturist,’ ” Small recounted. He instructed the card’s maker to include “research acupuncturist” because practicing acupuncture was illegal in California in 1972; nonetheless, he did house calls for free. Embodying the spirit of toolkit care, he described, “I had a bag with a needle pouch and electroacupuncture machines everywhere I went.”33

In 1980, Small and his wife Anola established the Harriet Tubman Medical Office, which operated until 2016. The upstairs room was dedicated to acupuncture, and Small largely resorted to the practice for pain management to prevent unnecessary drug use. “I try to avoid prescribing painkillers,” he explained.34 He has introduced thousands to acupuncture, including writer-activist Daphne Muse, who was treated for pain in the early 1970s.35 Small also taught patients points to needle themselves or apply pressure on themselves for pain relief.36 He performed acupuncture on his wife for her childbirths and on himself for his colonoscopy. To this day, he continues using acupuncture alongside his general practice.

The China trip exposed the delegation to an alternative form of therapeutic treatment and health care delivery. The lesson of community service and the integration of medical practices reinforced the revolutionaries’ toolkit care, and Small continues to see medicine as part and parcel of a broader commitment to societal transformation. He believes “there isn’t a Western or Eastern medicine, just one medicine—what helps the people.” Dedicated to “serving the people,” Small, at age 78 years, is “not ready to retire yet!”37

ACUPUNCTURE AS POLITICS

The history of Lincoln Detox, an acupuncture clinic in Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx, is rooted in radical politics. Known by the community as the “butcher shop” for the extreme mistreatment of patients and its dilapidated conditions, Lincoln Hospital was the only medical facility in the area by the 1970s.38 The Young Lords, BPP, and revolutionary health workers staged several takeovers at the hospital in 1970, demanding community self-efficiency with health care services.39 In November, they began a drug treatment program, later called Lincoln Detox, in the nurses’ residence to tackle the ravaging drug epidemic.40 The space functioned as a community gathering place, offering methadone treatments alongside political education courses.41

Posters distributed by the team featured skulls to represent oppressive forces, such as Eli Lilly, a prominent pharmaceutical company that manufactured and distributed methadone.42 Although methadone maintenance was the predominant detoxification treatment, community members viewed it as another method of sociopolitical regulation from the “white doctors, in white coats, in white hospitals.”43 The Lincoln Detox team believed the community was under attack by “chemical warfare” and “genocide,” whereby the American government was a “dope pusher,” creating a “methadone plague” and neglecting dire health care needs.44 Defense was to “organize,” “educate the people,” and employ acupuncture.45

The Lincoln team was an alliance of Black, Latinx, and White revolutionaries with varying sociopolitical backgrounds, united by a spirit of “collaboration and solidarity.”46 Prominent members included Walter Bosque and Vicente “Panama” Alba, both Young Lords activists.47 White doctors, such as Richard Taft, were also significant team members.48 Mutulu Shakur introduced the idea of using acupuncture to Lincoln.49 Formally part of the Republic of New Afrika, an organization that advocated for the liberation of several Southern states to the Black community, Shakur described himself as “a crucial liaison” to the BPP as he shared similar principles.50

In 1970, when car accidents left Shakur’s sons paralyzed, Shakur’s friend and fellow activist Yuri Kochiyama recommended acupuncture, a practice that was then known primarily within Asian American communities. His sons recovered, and Shakur described acupuncture as “a miracle,” fascinated that it was “non-chemical.” He noted that practitioners “didn’t wear traditional white coats,” which were associated with the poor treatment of minority communities.51 The team subsequently learned about acupuncture’s potential to treat withdrawal symptoms.52

The Lincoln team purchased affordable needles and learned from Chinatown practitioners, “picking up books, finding points in the ear, and trying on patients willing to give it a go.”53 Although toolkit care did not entail complicated technologies, it nonetheless required a learning process, as evidenced by the revolutionaries’ scrappy but dedicated endeavor to find what fit. In 1976, Shakur, Bosque, and others trained and received doctorates at the Montreal Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine, run by practitioners Oscar and Mario Wexu, who helped set up Lincoln’s acupuncture program in the early 1970s.54

Open to all, the acupuncture program treated more than 10 000 people within its first years, and treatment was paired with training in acupuncture and politics.55 The Lincoln team sought to develop “a barefoot doctor acupuncture cadre,” empowering communities to build their own toolkits. They visited China in 1977 with Mario Wexu and aimed to actualize Mao’s barefoot movement at home.56 They traveled around the United States teaching communities “the fundamentals of acupuncture . . . [and] how [the practice] was used in the revolutionary context in China.”57 Bosque described, “We used to say, ‘Each one, teach one.’ We started teaching each other.”58

The political significance of acupuncture was also embedded in the Chinese medical theory of the body’s innate abilities. The team taught that acupuncture was “a form of self-help therapy . . . the patient’s own rebalanced energy flow provides most of the health-giving relief.”59 As dominant sociopolitical forces rendered minority patients powerless, the concept that their very bodies were agents of health was significant, even subversive. This self-healing, importantly, also scaled to the community level, where “patients who were healed became practitioners who helped,” creating a self-sufficient, empowered collective.60 Acupuncture was not only a therapeutic but also a radical intervention of resistance and empowerment; disempowered communities were reclaiming the right to heal, which itself was healing.

Although these revolutionaries sought to “challenge Western occidental medicine by Eastern medicine” and criticized the medical establishment for its “patriotic” rejection of acupuncture, they did not dismiss biomedicine altogether. The Lincoln team advocated for scientific research on acupuncture “to give it legitimacy.”61 Western doctors, including Taft, “use[d] their licensing to benefit the people’s needs” by facilitating the state authorization of the program as a medical facility.62 The team used recognized research protocols, such as those of the National Institutes of Health, to measure acupuncture’s efficacy. This included a 20-bed inpatient unit where general detoxification methods were compared with methadone and acupuncture. “This was the most efficacious way to determine research results with statistics, case studies and findings,” Shakur recalled.63

In using biomedical tools for strategic means, the revolutionaries symbolized what Nelson described as not a blanket rejection of biomedical practices and scientific research but instead a “more rigorous engagement with them anchored in a conception of healthfulness that included freedom from medical discrimination and entitlement to social rights.”64 The employment of both biomedical methods and acupuncture signaled a crucial message: the “alternative” status of acupuncture read not as secondary, nor a last resort, but instead as preferred. Although certain biomedical interventions were available, especially methadone, the revolutionaries chose to rely on acupuncture. A drug-free and empowering practice with Maoist affiliations, acupuncture was a better fit for the revolutionaries’ toolkit, evidenced by the thousands of returning patients.65 However, important questions of the program’s longer-term efficacy remain, which call for more analyses.66

In November 1978, Mayor Edward Koch shut down Lincoln on allegations of fraud and the use of “questionable treatment methods.”67 This ended a years-long battle between government officials and the Lincoln team, beginning with the revolutionaries’ hospital takeovers. Alba described the constant “political struggle . . .to maintain funding, keep the program alive, against the local police as well as hospital police who continuously tried to make their way into the program (Lincoln Detox was a sanctuary where addicts could go and not be afraid of police).” With city and state bodies frequently threatening to cut funding, the team often protested. “Even though we forced the government for years to underwrite our work, eventually they had the power and took it out,” Alba stated.68 For Koch, “hospitals are for sick people, not for thugs,” and he was concerned with the revolutionaries’ direct actions and Lincoln’s network of radicals.69 Shakur emphasized that “acupuncture in the hands of the revolutionary-minded, particularly addressing addiction, was an intervention that the government was not willing to accept at the time.”70 More than 70 supporters gathered at Lincoln, holding signs that read “Reopen Detox, no methadone maintenance.”71

Shakur subsequently established the Black Acupuncture Advisory Association of North America (BAANA) in 1978, which trained hundreds of revolutionary-minded acupuncturists.72 Some members were linked to robberies, which they characterized as “expropriations”—the return of money from the rich to the poor from whom they had taken it.73 In 1982, Shakur, several BAANA members, and others were federally indicted under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act.74 The charges included their involvement in a Brinks armored car robbery in 1981, which led to the death of two policemen and one guard.75 Situated in the larger context of the 1960s and 1970s American underground movements in response to systematic suppression by local and federal law enforcement, the Black underground movement is particularly poorly documented, and this history is muddy on factual and moral dimensions.76 Complexity and multiplicity of truths pervade the history of Lincoln and BAANA, as public health and history strike a balance between celebrating the innovative use of acupuncture for addiction and community self-empowerment, on the one hand, and condemning the endangerment and taking of lives on the other.77

TOOLKIT CARE TODAY

Other Lincoln members founded a nearby successor program, called Lincoln Recovery. Known as “Phase Two,” this program did not offer political education but attracted socially oriented practitioners to train in ear acupuncture, many of whom worked on HIV/AIDS and addiction.78 However, many considered the original “program”—of acupuncture and politics—as having ended in November 1978.79 In 1985, Michael Smith, a White psychiatrist and director of Lincoln Recovery, formalized NADA and the five-point ear acupuncture protocol. Low-cost and efficient, the protocol is widely accessible for people of all backgrounds to receive or be trained in. From nurses to prison officers, the protocol was also used for first responders after the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks and Hurricane Katrina.80 As one practitioner declared: “It’s first aid!”81 Now a global organization, NADA has chapters from Great Britain to Japan, with an estimated 25 000 members.82

Lincoln also influenced the founding of other organizations. These include People of Community Acupuncture in the United States and Substance Misuse Acupuncture Register and Training (SMART UK) in England, where thousands of practitioners (either trained at Lincoln or trained by someone who was) employ toolkit care, working with marginalized populations at a sliding-scale rate or for free in group treatments.83 Although some practitioners are directly inspired by the Lincoln team, recognition and awareness of the early history have not always been at the forefront of these modern organizations, including NADA itself, a fact that is now changing under calls by community members.84

Small’s influence extends beyond his direct patient care since the 1970s. In Oakland, Freedom Community Clinic, whose founder was inspired by Small, has offered integrative medicine services since July 2019 to more than 2300 residents. Recently, the clinic organized pop-up “healing clinics” for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) patients in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the killing of George Floyd. At these clinics, acupuncture was offered alongside primary care checkups. BIPOC practitioners employed toolkit care similar to that used by the 1970s revolutionaries and provided alternative healing options. Their message resonated, and hundreds of BIPOC patients attended.85 Altogether, tens of thousands of practitioners, influenced by Small or the Lincoln team, practice integrative medicine, where medicine goes together with the social praxis of “serving the people, body and soul.”

Small and Lincoln members have never met.86 The varying degrees of sociopolitical motivation of its adherents attest to the multiplicity encompassed by the Black and broader revolutionary movement. The Lincoln team’s toolkit was far more politically oriented, evidenced by the political education emphasis. Yet the simultaneous and parallel nature of their acupuncture uptake powerfully underscores similar messages that provide guidance for today’s public health issues. With the current opioid epidemic resembling the conditions of the 1970s drug crisis, the revolutionaries’ use of acupuncture offers a holistic image of prevention and care—acupuncture for pain management on the one hand and its pairing with social empowerment for addiction management on the other. Importantly, thousands of patients attest to its benefits.87 These stories contrast with the current understanding of CAM practices, as mostly used by White patients.88 The contributions and innovations to the addiction field and beyond by these revolutionaries have not been properly recognized by public health; political and conceptual occlusions from incomplete historical understandings of the Black and broader revolutionary movement and the dismissal of addiction interventions as only relevant to addiction have kept these histories from getting the attention and critical engagement they deserve.

Although medical practices with sociopolitical involvement are not new, they are seldom taught in public health, medical, and other health science schools.89 But the lessons of their successes—and failures—in holistic health care delivery are widely applicable.90 We must understand the facilities of (in)justice and conditions that made Lincoln possible—and then not. We must also evaluate the agency of the Lincoln team and how they were made into and made themselves targets of the state, which led to the cessation of a pioneering public health program. We ask, what features of Lincoln could be successful today? We may also wonder, was Small’s intentional peripherality what allowed him to sustain his practice?

What is clear is that the revolutionaries’ integration of medical with social practices broadens our conceptualization of health care. What sustained the reception of acupuncture was its ability to satisfy particular needs, which were not always medical but were nonetheless constituent of health. These lesser-known histories not only suggest the importance of considering medical needs together with social needs, but they also highlight their interplay, encouraging us to address the multiple axes that constitute the healing process. They impress on us the indispensability of attending to local needs and provide a practical vision of a modern barefoot doctor and grassroots implementation of toolkit care. Above all, these important histories should move us to pay attention to the creative and complex ways in which oppressed communities define, envision, and seek health as they lay claim to a fundamental human right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was adapted from my undergraduate thesis advised by Shigehisa Kuriyama, to whom I am deeply grateful. I extend my gratitude also to Allan M. Brandt and Alyssa Botelho, my thesis readers. Many thanks to Naomi Rogers and David S. Jones, for insightful conversations and invaluable feedback; and also to my two excellent anonymous reviewers, Daniel Burton-Rose, Anant T. Pai, M. Yishai Barth, and Marie Louise James. Special thanks to Mia Donovan for providing access to archives and lending her knowledge of the Lincoln events. Finally, Tolbert Small, David Levinson, members of Shakur’s support team, Laura Cooley, Elizabeth Ropp, and other interlocutors whose time and energy in relaying these stories to me are most appreciated. For a short, visual presentation of the histories of Small and Shakur with the Harvard University Asia Center, see https://youtu.be/lyPv4hQYm3o?t=38.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

See also Reverby, p. 760.

ENDNOTES

- 1. In continuation with previous articles in this Journal—such as the ones I reference below—I will be standardizing the capitalization of the first letter of racial groups.

- 2. “About,” National Acupuncture Detoxification Association, available at https://acudetox.com (accessed October 15, 2020). By “treatment,” I indicate the broader definition of illness and disease management, which encompasses both care and cure. Addiction is notoriously difficult to cure, as there is little consensus on the definition of “cure” itself.

- 3. “Conversation in Group Setting at Hope for New Hampshire,” interview by author, October 23, 2018.

- 4.Clarke Tainya C., Black Lindsey I., Stussman Barbara J., Barnes Patricia M., Nahin Richard L. “Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults: United States, 2002–2012,” National Health Statistics Reports 79 (February 10, 2015): 1–16. Of this population, the largest group of CAM users in 2012 were non-Hispanic White adults (37.9%) and those that were not poor (38.4%). “Not poor” is defined as persons who have incomes 200% of the poverty threshold or greater.

- 5. For excellent overviews of the BPP, see Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2016); Donna Jean Murch, Living for the City Migration: Education and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California (Chapel Hill, NKC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010). For the Young Lords, see Johanna Fernández, The Young Lords: A Radical History (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2020). Note that although the use of “Latinx” is anachronistic for this time period, I follow Fernández’s use of the term. See Fernández, The Young Lords, 5.

- 6. Refer to footnote 39 for references about the Lincoln events. For specific coverage of Shakur’s work at Lincoln, see Susan Reverby, Co-Conspirator for Justice: The Revolutionary Life of Dr. Alan Berkman (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2020); Dope Is Death, documentary directed by Mia Donovan (Montreal, Canada: EyeSteel Film, 2020); Mia Donovan, Dope Is Death, podcast audio, August 31, 2020, available at https://dopeisdeath.com (accessed October 20, 2020)

- 7. Based on conversations with Small, I take his definition of “revolutionary,” which represents “people that wanted to change society for the better.” This does not necessarily refer to someone with the agenda of overthrowing governments. Small considers himself to be a revolutionary, despite not formally being part of a radical party.

- 8. Small has been mentioned for his health care work with the BPP at the party’s free clinic in Oakland and the national sickle cell anemia project. Lacking, however, is an analysis of his use of acupuncture. The most coverage on Small’s work is thus far with Alondra Nelson, “The Longue Durée of Black Lives Matter,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no 10 (2016): 1734–1737, https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2016.303422; Alondra Nelson, Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 71, 97, 181–182. See also Lewis Cole, ed., Columbia University Black Panther Project: Interview of Dr. Tolbert Small by Lewis Cole (Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street Press, 2005); E. Schiller, Community Health Activism of The Black Panther Party (BA Honors Thesis, University of Michigan, 2008); Stephen Shames and Bobby Seale, “Healthcare,” in Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers (New York: Abrams, 2016), 102–107. For Small’s personal Web site, see “Home,” Dr. Tolbert Small, The People’s Doctor, July 27, 2020, available at http://the-peoples-doctor.com (accessed October 20, 2020)

- 9. They also make significant contributions to the fields of Chinese medicine and African American studies, in which they have also received little attention, especially the work of Small in comparison to the Lincoln events.

- 10. For examples of reputable American Chinese medicine schools, see “Chinese Medicine,” American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, available at https://www.actcm.edu/chinese-medicine (accessed November 2, 2020); M. Harris, “The Birth of Acupuncture: History of Acupuncture,” Pacific College, October 24, 2019, available at https://www.pacificcollege.edu/news/blog/2019/01/25/the-birth-of-acupuncture-history-of-acupuncture (accessed November 2, 2020). For examples of biomedical institutions, see “Traditional Chinese Medicine,” Mount Sinai Health System, available at https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/treatment/traditional-chinese-medicine (accessed November 2, 2020). See also William L. Prensky, “Reston Helped Open a Door to Acupuncture,” The New York Times, December 14, 1995, available at http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/109511141?accountid=11311 (accessed November 2, 2020). For Reston’s original article, see James Reston, “Now, About My Operation in Peking,” The New York Times, July 26, 1971, available at http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/health/1971acupuncture.pdf (accessed November 2, 2020)

- 11. Based on conversations and observations, I contend that “toolkit care” is a viable description of the ethos of the Lincoln team, Small, and modern practitioners of (ear) acupuncture with sociopolitical motivations. Small describes bringing a bag of needles and electroacupuncture machines with him as he did house calls. Modern practitioners, just like the Lincoln team, carry needles as they move around the country. The ease of transportability of acupuncture lends itself well to toolkit care, a notion that can be extrapolated and broadly applied. See the explicit use of “clinical toolkit” by ear acupuncturists, “Trauma Prevention and Recovery Protocols/Clinical Toolkit,” Acupuncturists Without Borders, August 7, 2020, available at https://acuwithoutborders.org/rsh-module-2 (accessed October 20, 2020)

- 12. NADA trainers have written explicitly about the notion of “healthcare for the people by the people” and service, especially in the face of difficult, stigmatized conditions such as addiction or mental health, or in response to emergencies. They term this the “spirit of NADA.” See Claudia Voyles, Kenneth Carter, and Laura Cooley, “Back to the Future: The National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA) Protocol Persists as an Agent of Social Justice and Community Healing by the People and for the People,” Open Access Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine 2, no. 4 (2020): 191–193, [DOI]

- 13. “Serving the people, body and soul” was a famous BPP aphorism, borrowed from Mao Zedong’s writings. See Mary T. Bassett, “No Justice, No Health: The Black Panther Party’s Fight for Health in Boston and Beyond,” Journal of African American Studies 23, no. 4 (2019): 352–363, ;Nelson, Body and Soul , 1. [DOI]

- 14. The influence of Mao Zedong and Maoism on the BPP can be found in many writings by Panther members. See Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story (New York, NY: Anchor Books, 1994), 295–304; Huey P. Newton, Revolutionary Suicide (London, UK: Penguin Books, 2009), 322–326, 348–353; Bobby Seale, Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton (Baltimore, MD: Black Classic Press, 1991), 79–85; David Hilliard and Lewis Cole, This Side of Glory: The Autobiography of David Hilliard and the Story of the Black Panther Party (Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books, 1993), 118–121. For a few excellent secondary literature sources, see Bloom and Martin, Black Against Empire, 1–3, 66, 69, 311, 349–350; M. D. Johnson, “From Peace to the Panthers: PRC Engagement With African-American Transnational Networks, 1949–1979,” Past & Present 218, no. suppl 8 (January 2013): 233–257, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gts042; Robin D. G. Kelley and Betsy Esch, “Black Like Mao,” in Afro Asia (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 97–154, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822381174-008; Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History (London, UK: The Bodley Head, 2019), 292–293; Murch, Living for the City, 6, 132, 142; Nelson, Body and Soul, 69.

- 15. Nelson, Body and Soul, xi.

- 16.Morabia Alfredo. Unveiling the Black Panther Party Legacy to Public Health. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303405. 106, no. 10 (2016): 1732c1733, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lovell, Maoism, 293; Nelson, Body and Soul, 70.

- 18. Xiaoping Fang, Barefoot Doctors and Western Medicine in China (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2015), 19, Ch. 3, 4. See also Xun Zhou, The People’s Health: Health Intervention and Delivery in Mao’s China, 1949–1983 (Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020).

- 19. While the original 10-point platform in 1966 did not explicitly include the demand for health care (it was incorporated in the 1972 revision, replacing the demand for the exemption of Black men from military service), BPP members and affiliates were enacting community health care work early on. The first People’s Free Medical Clinics were established in 1968 in Kansas City and Chicago. See Mary T. Bassett, “Beyond Berets: The Black Panthers as Health Activists,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 10 (2016): 1741–1743, ; Nelson, Body and Soul , 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20. “Conversation with Dr. David Levinson,” interview by author, February 8, 2019.

- 21.College and School News, Crisis. 71, no. 1 (1964): 55, available at https://books.google.com/books?id=7FsEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA55 (accessed October 20, 2020)

- 22.Tolbert Small, “Black Genocide. Sickle Cell Anemia,” The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, April 10, 1971, 10–11, available at https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/black-panther/06%20no%2011%201-20%20apr%2010%201971.pdf (accessed October 20, 2020); “Lecture From Dr. Tolbert Small On Sickle Cell Anemia And David Hilliard On Black Panther Movement,” available at https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7C3156547 (accessed October 30, 2020). See also Nelson, Body and Soul, 97, 122.

- 23. See Nelson, Body and Soul, 146; Morabia, “Unveiling the Black Panther Party Legacy to Public Health.”. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. Newton and fellow Panthers Elaine Brown and Robert Bay visited China together in September 1971 for 10 days. In his memoir, Newton writes of the “strange yet exhilarating experience” to travel to China and witness “the revolutionary process,” and concludes his chapter on China by quoting Mao’s statement, “If you know the theory and methods of revolution, you must take part in revolution. All genuine knowledge originates in direct experience.” See Newton, Revolutionary Suicide, 348–353. While he does not mention asking the Chinese Communist Party about sending the 1972 BPP delegation, Small and Levinson recall Newton making the request. Thus far, no documents exist to corroborate the exact origins of who initiated the idea for the delegation, but given what Newton writes about the importance of “direct experience” and high praise of his time in China, it seems likely he would make such a request. See also Brown, A Taste of Power, 296–304.

- 25. “Progressive Americans, Led by Panthers, Return from China,” The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, April 22, 1972, 8th edition, sec. 5, available at https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/black-panther/08%20no%205%201-20%20apr%2022%201972.pdf (accessed October 20, 2020). A few other newspapers reported on the trip; for example see “Bay Black Panthers Enroute to R. China,” San Francisco Examiner, March 6, 1972, 1, 12; “Black Panther Party Members on Way to China,” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1972, 2; “Panthers, Others Off to Red China,” Sun Reporter, March 11, 1972, 2.

- 26. “Conversation with Dr. David Levinson.” Levinson was part of the Intercommunal Survival Communities to Combat Fascism (ISCCF), the BPP’s multiracial network working to promote the party’s survival programs. He was also a member of the Lumpen, the BPP’s R&B band. His parents, Cec and Saul Levinson, founded the Huey Newton Defense Committee as well as the Berkeley chapter of the National Committees to Combat Fascism (later renamed ISCCF). See Peter Gilstrap, “Power to the People: Inside the Black Panthers’ R&B Band, the Lumpen,” KCRW, June 18, 2020, available at https://www.kcrw.com/culture/shows/lost-notes/black-panther-band-lumpen-lost-notes (accessed October 20, 2020); Y. Litvin, “The Black Panther Party’s Multiracial Anti-Fascism,” ROAR Magazine (Foundation for Autonomous Media, August 27, 2020), available at https://roarmag.org/essays/black-panther-multiracial-antifascism (accessed October 20, 2020);Schiller, Community Health Activism.

- 27. Fang, Barefoot Doctors and Western Medicine in China, 2, 67.

- 28. “Lecture in Workers, Peasants, Soldiers Hospital in Peking,” March 27, 1972, Beijing, China, 1:08:51, Tolbert and Anola Small Papers.

- 29. “Conversation with Dr. David Levinson.”.

- 30. Levinson returned home and volunteered at an acupuncture conference organized by Frederick Kao, a preeminent practitioner in New York who founded The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. See Bruce Lambert, “Frederick Kao, 73, Educator Who Led Acupuncture Effort,” New York Times, July 31, 1992, available at https://www.nytimes.com/1992/07/31/nyregion/frederick-kao-73-educator-who-led-acupuncture-effort.html (accessed October 20, 2020). Later, Levinson moved to New York City and worked for Kao in a research program investigating the use of acupuncture for hearing loss. In 1981, Levison received a medical degree at the University of California, San Francisco, and became an emergency physician. He has worked with revolutionaries around the world, including in El Salvador and Chiapas. Most recently, he volunteered at an Oakland integrative medicine clinic for undocumented immigrants, where a primary care office sits adjacent to an herbal dispensary.

- 31. “Conversation with Dr. Tolbert Small,” interview by author, February 9, 2019. Similar to Small, a number of other American physicians (visiting China as part of medical delegations) were inspired by the barefoot doctors’ movement. See, for example, Victor W. Sidel, “The Barefoot Doctors of the Peoples Republic of China,” New England Journal of Medicine 286, no. 24 (1972): 1292–1300, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm197206152862404; “Wald Lectures on Chinese Medicine,” Harvard Crimson, March 24, 1972, available at https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1972/3/24/wald-lectures-on-chinese-medicine-pthis (accessed November 2, 2020)

- 32. The book Small used to teach himself acupuncture was an English translation of zhongguo zhenjiuxue gaiyao, a Chinese medicine book by the Editorial Committee for Acupuncture and Moxibustion of the People’s Health Publishing House. The translation was done by Lee Hsu on the commission of David Bacon, an activist, photojournalist, and former volunteer at the George Jackson Clinic while Small was the medical director. The Chinese text was acquired from China Books in San Francisco. Lee Hsu’s translation, entitled Basic Acupuncture Techniques—which includes an introduction written by Small—was never published due to lack of funding. Small retains a copy of the manuscript. Eventually, an English version of the same Chinese text was released in 1980 by the Foreign Languages Press; see Essentials of Chinese Acupuncture, 1st ed. (Beijing, China: Foreign Languages Press, 1980).

- 33. “Conversation with Dr. Tolbert Small,” interview by author, October 30, 2020.

- 34. “Conversation with Dr. Tolbert Small,” interview by author, August 25, 2019.

- 35. Daphne Muse, personal communication with author, August 13, 2020.

- 36. “Conversation with Dr. Tolbert Small,” October 30, 2020.

- 37. “Conversation with Dr. Tolbert Small,” interview by author, August 26, 2019.

- 38.Meléndez Miguel. “ ‘The Butcher Shop’: Lincoln Hospital,” in We Took the Streets: Fighting for Latino Rights With the Young Lords (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005), 162–178; Merlin Chowkwanyun, “The New Left and Public Health the Health Policy Advisory Center, Community Organizing, and the Big Business of Health, 1967–1975,” American Journal of Public Health 101, no. 2 (2011): 238–249, . Note that amongst a series of medical neglect and discrimination cases, there was the infamous case of Carmen Rodriguez, a young woman who was believed to be “butchered in the hospital,” and bled to death on a gurney. See Jennifer Nelson, More Than Medicine: A History of the Feminist Women’s Health Movement (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2015), 52–54. [DOI]

- 39.Vicente “Panama” Alba, “Lincoln Detox Center. The People’s Drug Program,” interview by Molly Porzig, The Abolitionist, March 15, 2013, available at https://abolitionistpaper.wordpress.com/2013/03/15/lincoln-detox-center-the-peoples-drug-program (accessed January 7, 2019); Chowkwanyun, “The New Left and Public Health.” The history of the Lincoln events is much more expansive than what I have laid out here; see Chowkwanyun, Fernández, and Reverby (previously cited works) and others for a more complete account. See also Alondra Nelson, “ ‘Genuine Struggle and Care’: An Interview With Cleo Silvers,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 10 (2016): 1744–1748, https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2016.303407.

- 40. Reverby, Co-Conspirator for Justice, 91; Martin Tolchin, “South Bronx: A Jungle Stalked by Fear, Seized by Rage,” January 15, 1973, available at https://www.nytimes.com/1973/01/15/archives/south-bronx-a-jungle-stalked-by-fear-seized-by-rage-the-south-bronx.html; (accessed October 20, 2020); see also Fernández, The Young Lords, 303.

- 41. “2018 Interview about Acupuncture & The Opioid Crisis,” interview by Steven Michael Hinshaw, Mutulu Shakur, December 9, 2017, available at http://mutulushakur.com/site/2018/11/acupuncture-interview (accessed January 3, 2019)

- 42. Due to copyright issues, this poster, printed in 1975, cannot yet be published. However, the poster can be viewed in Donovan’s documentary, Dope Is Death.

- 43. As described by historian Samuel Roberts, who is currently working on a project on the political history of heroin addiction treatment, in an interview; see Olga Khazan, “How Racism Gave Rise to Acupuncture for Addiction Treatment,” The Atlantic, August 3, 2018, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/08/acupuncture-heroin-addiction/566393 (accessed December 10, 2018). For a history of how methadone maintenance became standardized in New York City, see Samuel Roberts, “ ‘Rehabilitation’ as Boundary Object: Medicalization, Local Activism, and Narcotics Addiction Policy in New York City, 1951–62,” The Social History of Alcohol and Drugs 26, no. 2 (2012): 147–169, https://doi.org/10.1086/shad26020147.

- 44. Shakur, interview by Hinshaw; Radical Roots of Acupuncture, Dope Is Death, podcast audio, August 31, 2020, available at https://dopeisdeath.simplecast.com/episodes/two (accessed September 1, 2020)

- 45. The words “organize,” “educate the people,” and “acupuncture heals,” along with the imagery of a needling hand, can be seen in the 1975 poster, which can be viewed in Donovan’s Dope Is Death. See also “Acupuncture Used to Treat Addiction,” Press & Sun-Bulletin, June 5, 1976, p. 3-A.

- 46. Alba, interview by Porzig.

- 47. Ibid; Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard, “How the Young Lords Took Lincoln Hospital, Left a Health Activism Legacy,” Filter (The Influencer Foundation Inc, November 9, 2018), available at https://filtermag.org/how-the-young-lords-took-lincoln-hospital-and-left-a-health-activism-legacy (accessed October 20, 2020)

- 48. “In Memory of Richard Taft,” White Lightning, 1974, available at http://www.freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/DOC58_scans/58.White.Lightening.RichardTaft.pdf (accessed November 2, 2020). The extent of Taft’s contribution to the program is unclear. While some literature suggests that he was interested in Chinese medicine (perhaps even having gone to China himself) and recommended acupuncture to the Lincoln cohort, original members of the team, such as Bosque, recall Shakur mentioning the practice first. Later practitioners state that Taft’s name was often strategically used as a way to legitimize the practice.

- 49. Blanchard, “How the Young Lords Took Lincoln Hospital”; Shakur, interview by Hinshaw.

- 50. Edward Onaci, Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2020).

- 51. Shakur, interview by Hinshaw.

- 52. Various team members report Shakur initially reading about research conducted in Hong Kong for the use of acupuncture for withdrawal symptoms or about a doctor in Bangkok using the practice as an analgesic. The order is unclear, but it is clear that both articles influenced the team. For the New York Times article, see “Hong Kong Doctors Use Acupuncture to Relieve Addicts’ Withdrawal Symptoms,” New York Times, April 5, 1973, available at https://www.nytimes.com/1973/04/05/archives/hong-kong-doctors-use-acupuncture-to-relieve-addicts-withdrawal.html (accessed November 2, 2020). For the original research, see H. L. Wen and S. Y. C. Cheung, “Treatment of Drug Addiction by Acupuncture and Electrical Stimulation,” Asian Journal of Medicine 9, no. 138 (April 1973): 138–141. The article about the Bangkok doctor is yet to be located.

- 53. Shakur, interview by Hinshaw.

- 54. Haki Shakur, personal communication with author, May 30, 2020; “Conversation With Mario Wexu,” interview by author, September 10, 2020.

- 55. “In Memory of Richard Taft”; Voyles, Carter, and Cooley, “Back to the Future”; “Conversation With Mario Wexu”; Dope Is Death, directed by Mia Donovan. Various documents, accounts, and people state conflicting start dates for the acupuncture program. This is likely due to different definitions of the origin—when the team reached out to Chinatown practitioners, when they started experimenting with needles on each other, when they started treating patients, or when the program was standardized and scaled. The contested years are 1972, 1973 and 1974.

- 56. “Conversation With Mario Wexu.”.

- 57. “The Use of Acupuncture by Revolutionaries: An Interview With Brother Tyehimba,” August 31, 2014, available at http://mutulushakur.com/site/1992/10/interview-on-acupuncture (accessed October 20, 2020)

- 58. Blanchard, “How the Young Lords Took Lincoln Hospital.” “Each one, teach one” was a common phrase employed by the BPP. See, for example, “Political Education—Oakland, CA,” It’s About Time, available at http://www.itsabouttimebpp.com/Our_Stories/Chapter4/Political_Education.html (accessed October 20, 2020)

- 59. Shakur, interview by Hinshaw.

- 60. July Membership Café, National Auricular Detoxification Association, July 15, 2020, available at https://acudetox.com/july-membership-cafe (accessed September 2, 2020). Readers may notice that the use of acupuncture at Lincoln was deeply rooted in community, and self-empowerment translated directly to and initiated community empowerment. Self-care meant community care. This is peculiar, as American acupuncture has largely been seen as part of the individualistically rooted movement of wellness and self-help. This history of community-rooted acupuncture thus argues for another historical understanding of acupuncture specifically and self-care generally.

- 61. Shakur, interview by Hinshaw.

- 62. Reverby, Co-Conspirator for Justice, 67. Other White doctors used their medical license to support Lincoln and later with BAANA, such as Barbara Zeller.

- 63. Shakur, interview by Hinshaw.

- 64. Nelson, “The Longue Durée of Black Lives Matter.”. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65. For patient accounts, see “In Memory of Richard Taft.”.

- 66. Ibid.

- 67.Ronald Sullivan. “Leaders of Drug Unit at Lincoln Removed on Orders From Koch,” New York Times, November 29, 1978, available at https://www.nytimes.com/1978/11/29/archives/leaders-of-drug-unit-at-lincoln-removed-on-orders-from-koch-unit.html (accessed November 2, 2020). Then-assemblyman Chuck Schumer also claimed that there was $1 million in unsubstantiated payroll costs, which was contested by members of the city’s Health and Hospital Corporation. See David Medina, “1M Payroll Gap in Dope Clinic's Audit Denied,” Daily News, November 15, 1977, 8.

- 68. Alba, interview by Porzig; Blanchard, “How the Young Lords Took Lincoln Hospital.” For example, in response to the Health and Hospital Corporation firing of employees at the detox program, the activists took to direct action, which ranged from peaceful protesting to property damage. See “Seize Health Offices to Protest Firings,” Daily News, September 25, 1975, 7; Hugh Wyatt, “Delay Detox Firings in Lincoln Protest,” Daily News, September 26, 1975, 7.

- 69. Sullivan, “Leaders of Drug Unit at Lincoln Removed on Orders From Koch.”.

- 70. Shakur, interview by Hinshaw.

- 71.Ronald Sullivan. “Countercharges by Lincoln Drug Unit,” New York Times, November 30, 1978, available at https://www.nytimes.com/1978/11/30/archives/countercharges-by-lincoln-drug-unit-fear-of-disturbance-eases.html (accessed November 2, 2020)

- 72. Reverby, Co-Conspirator for Justice, 86, 93. See also The Students of the Black Acupuncture Association of North America, “Open Letter From the Students of BAANA,” Mutulu Shakur, January 1, 1985, available at http://mutulushakur.com/site/1985/01/open-letter-from-baana (accessed November 2, 2020)

- 73. Reverby, Co-Conspirator for Justice, 93.

- 74. BAANA included members of the May 19th Communist Organization, a collective of White revolutionaries who supported the self-defense of communities of color. Activist Marilyn Jean Buck was a connection between BAANA and May 19th and was tried and convicted of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization conspiracy (which included the 1981 Brinks case) along with Shakur. See Reverby, Co-Conspirator for Justice, 95, 111.

- 75. The 1981 Brinks case, and specifically Shakur’s involvement, is highly contested. Conflicting sources present different pictures; Shakur, although not on the scene, was alleged to be a mastermind of the robbery (and several other expropriations). This has been disputed by his legal team and several others. This complex history requires far more exploration, which I will grapple with further in my future work. For purposes of this article, I focus on the revolutionaries’ innovations in acupuncture, which, although they should not be understood separately from its context, can be highlighted. This article, then, serves as a call for scholars to delve deeper into this intricate history. For readers interested in a few (highly polarized) accounts of the Brinks case, see “Case Facts,” Mutulu Shakur, January 19, 2017, available at http://mutulushakur.com/site/case-facts (accessed October 20, 2020); Kuwasi Balagoon, Matt Meyer, and Karl Kersplebedeb, A Soldier’s Story: Revolutionary Writings by a New Afrikan Anarchist (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2019); Dan Berger, Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2006), 263–280; John Castellucci, The Big Dance: The Untold Story of Kathy Boudin and the Terrorist Family That Committed the Brink’s Robbery Murders (New York, NY: Dodd, Mead, 1986); Dope Is Death, podcast audio, August 31, 2020; Reverby, Co-Conspirator for Justice, 109–116.

- 76. On grappling with the complex 1960s and 1970s American underground and radical histories, a few fine sources are Dan Berger, ed., The Hidden 1970s: Histories of Radicalism (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010); Daniel Burton-Rose, ed., Creating a Movement With Teeth: A Documentary History of the George Jackson Brigade (Oakland, CA: PM, 2010); Laura Pulido, Black, Brown, Yellow, and Left Radical Activism in Southern California (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006); Jeremy Varon, Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and the Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004). The Black underground movement, however, has been most poorly documented. See, for example, Akinyele O. Umoja, “Repression Breeds Resistance: The Black Liberation Army and the Radical Legacy of the Black Panther Party,” in Kathleen Cleaver and George Katsiaficus, Liberation, Imagination, and the Black Panther Party (New York, NY: Routledge, 2001), 3–19.

- 77. For a deeply insightful and important piece on how historians think through the questions of moral judgement, crafting meaningful narratives and balancing the multiplicity of truths, all while acknowledging one’s own perspective, bias, and inevitable places of ignorance, see Susan M. Reverby, “Enemy of the People/Enemy of the State: Two Great(ly Infamous) Doctors, Passions, and the Judgment of History,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 88, no. 3 (2014): 403–430, [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78. July Membership Café; National Acupuncture Detoxification Association.

- 79. Alba, interview by Porzig; Blanchard, “How the Young Lords Took Lincoln Hospital.”.

- 80.Kenneth Carter Michelle Olshan-Perlmutter, “NADA Protocol. ” Journal of Addictions Nursing 25, no. 4 (2014): 182–187, https://doi.org/10.1097/JAN.0000000000000045. The NADA protocol is also employed at the Substance Abuse Treatment Unit run by the Connecticut Mental Health Clinic (a partnership between Yale School of Medicine and State of Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services), where psychiatry interns can be trained in administering the treatment. See Lucile Bruce, “Ear Acupuncture: A Tool for Recovery,” Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, November 14, 2011, https://medicine.yale.edu/psychiatry/newsandevents/cmhcacupuncture (accessed November 2, 2020) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81. “Conversation With Elizabeth Ropp,” interview by author, July 22, 2020.

- 82.Elizabeth Stuyt, Claudia Voyles, Sara Bursac “NADA Protocol for Behavioral Health. Putting Tools in the Hands of Behavioral Health Providers: The Case for Auricular Detoxification Specialists. doi: 10.3390/medicines5010020. Medicines 5, no. 1 (July 2018): 20, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eana X. Meng, “Needles to Needles: How Ear Acupuncture Can Work for Substance Use Recovery. Somatosphere. September 15, 2020, http://somatosphere.net/2020/needles-to-needles-ear-acupuncture.html (accessed September 16, 2020). There are many more programs that employ the five-point ear acupuncture protocol, although they do not always use the term “NADA” protocol in order to separate themselves from the NADA organization. See, for example, “Vision, Mission, and Strategy,” Acupuncturists Without Borders, available at https://acuwithoutborders.org/vision-mission-and-strategy (accessed November 6, 2020); “The Treatment,” Pathways to Health, available at http://www.pathwaystohealth.org.uk/treatment.html (accessed November 6, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 84. For example, acupuncturist Tenisha Dandridge, inspired by Shakur and BAANA, set up the Black Acupuncturist Association in 2020. See “Home,” Black Acupuncturist Association, available at https://www.blackacupuncturist.com (accessed November 6, 2020). For NADA’s recent support for Shakur, see “National Acupuncture Detoxification Association Support for Dr. Mutulu Shakur,” Mutulu Shakur, August 2, 2020, available at http://mutulushakur.com/site/2020/08/national-acupuncture-detoxification-association-support (accessed November 2, 2020)

- 85. “Bay Area Rapid Response Healing for Black Lives,” Freedom Community Clinic, June 2020, available at https://www.freedomcommunityclinic.org (accessed October 20, 2020)

- 86. Small and Shakur later came to know of each other’s work, with Small planning to visit the South Bronx in the late 1970s. Unfortunately, however, he fell ill and could not make the trip.

- 87. Many patients have reported the benefits of acupuncture for helping with addiction—for Lincoln patients, see “In Memory of Richard Taft.” For modern-day NADA patients, see Jane Healey, “Pathways to Health Annual Report 2019–2020” (Pathways to Health: Brighton and Hove, 2020). See also Ryan Bemis, “Evidence for the NADA Protocol: Summary of Research,” National Acupuncture Detoxification Association, 2013, available at https://acudetox.com/evidence-for-the-nada-protocol-summary-of-research (accessed November 2, 2020). For testimonies of the effectiveness of acupuncture and political empowerment for patients, see, for example, Acupuncture Needles—Tools of Healing or Rebellion?, Dope Is Death, podcast audio, August 31, 2020, available at https://dopeisdeath.simplecast.com/episodes/three (accessed September 1, 2020). The question of efficacy for acupuncture (whether alone or as paired with political empowerment) is as complex as the notion of effective “cure” for addiction; it is difficult to “measure” efficacy when there is little consensus on what and how to measure. I would also be remiss not to acknowledge the question of the placebo effect. The field of anthropology, however, offers important frameworks to our understanding of acupuncture, and the complexities of translating a practice based in a different kind of body philosophy into the biomedical lexicon. It advocates for a more holistic understanding of efficacy, and for the patient experience to be taken seriously. An excellent overview is Linda L. Barnes, “American Acupuncture and Efficacy: Meanings and Their Points of Insertion,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 19, no. 3 (2005): 239–266, https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2005.19.3.239.

- 88. In a study conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics on data from 2002–2012, the largest population of CAM users are Non-Hispanic White, a trend that increased during the decade. Non-Hispanic Blacks had not only the lowest rate of CAM utilization, but the percentage decreased over time. This history is a needed correction to the understanding that CAM practices have, outside of Asian communities, only been largely engaged with by White populations since Reston’s article. See Tainya C. Clarke et al., “Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012,”National Health Statistics Reports 79 (2015): 1-16.

- 89. There is an increasing focus on the entwinement of health care and social movements in the United States in the 20th century. A few key texts are Anne-Emanuelle Birn and Theodore M. Brown, Comrades in Health: US Health Internationalists, Abroad and at Home (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013); Merlin Chowkwanyun and Benjamin Howell, “Health, Social Reform, and Medical Schools—The Training of American Physicians and the Dissenting Tradition,” New England Journal of Medicine 381, no. 19 (2019): 1870–175, ; John Dittmer, The Good Doctors: the Medical Committee for Human Rights and the Struggle for Social Justice in Health Care (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2017); Elizabeth Fee and Theodore Brown, ed., Making Medical History: The Life and Times of Henry E. Sigerist (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997); Naomi Rogers, “Caution: The AMA May Be Dangerous to Your Health: The Student Health Organizations and American Medicine 1965–1970,” Radical History Review 80 (2001): 5–34; Sigrid Schmalzer, Daniel S. Chard, and Alyssa Botelho, Science for the People: Documents From America’s Movement of Radical Scientists (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2018) [DOI]

- 90. Important missing analysis and next steps include delving deeper into the “efficacy” of the Lincoln acupuncture program in the long run. How successful was it in the long term? By what measures? What happened to the thousands of people who visited the program? Did they continue with acupuncture treatment when Lincoln relocated? What happened at Lincoln, and what unfolded afterwards, promise to be a fruitful place of investigation for the field of addiction and public health at large.