Abstract

Objective:

Contingency management (CM) is often criticized for limited long-term impact. This meta-analysis focused on objective indices of drug use (i.e., urine toxicology) to examine the effects of CM on illicit substance use up to 1 year following treatment.

Method:

Analyses included randomized trials (k = 23) of CM for stimulant, opioid, or polysubstance use disorders that reported outcomes up to 1 year after the incentive delivery had ended. Using random effects models, odds ratios (OR) were calculated for the likelihood of abstinence. Metaregressions and subgroup analyses explored how parameters of CM treatment, namely escalation, frequency, immediacy, and magnitude of reinforcers, moderated outcomes.

Results:

The overall likelihood of abstinence at the long-term follow-up among participants who received CM versus a comparison treatment (nearly half of which were community-based comprehensive therapies or protocol-based specific therapies) was OR = 1.22, 95% confidence interval [1.01, 1.44], with low to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 36.68). Among 18 moderators, longer length of active treatment was found to significantly improve long-term abstinence.

Conclusions:

CM showed long-term benefit in reducing objective indices of drug use, above and beyond other active, evidence-based treatments (e.g., cognitive–behavioral therapy, 12-step facilitation) and community-based intensive outpatient treatment. These data suggest that policymakers and insurers should support and cover costs for CM, which is the focus of hundreds of studies demonstrating its short-term efficacy and, now, additional data supporting its long-term efficacy.

Keywords: contingency management, urine toxicology, drug treatment, meta-analysis

Many patients with substance use disorders successfully reduce or cease drug use while involved in treatment programs (Davis et al., 2016; Dutra et al., 2008; Irvin et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2015; Lundahl et al., 2010; Magill & Ray, 2009; Magill et al., 2019; Roozen et al., 2004; Sayegh et al., 2017). However, relapse rates are high (McLellan et al., 2000), and substance use disorders are widely conceptualized as chronic relapsing conditions (Arria & McLellan, 2012; McLellan et al., 2000). As such, treatment effects often diminish following the conclusion of most active treatments (Benishek et al., 2014; Magill et al., 2009), and efforts to identify treatments with lasting impact are essential for improving overall substance-use outcomes.

Contingency management (CM) treatment is based on the theory of operant conditioning. CM provides immediate, tangible reinforcers upon objective evidence of behavior change (e.g., submission of drug negative urine samples). CM offers immediate positive consequences for choosing not to use substances that compete with the positive aspects of drug use, providing a bridge to the more substantial, but often very delayed benefits of recovery (i.e., employment, improved relationships; Petry, 2012). CM has the largest effect size of any psychosocial treatment for reducing drug use during treatment (g = 0.54; Dutra et al., 2008) yet remains one of the least likely evidence-based substance use disorder treatments to be offered in clinical settings (Benishek et al., 2010; Herbeck et al., 2008; McGovern et al., 2004; Willenbring et al., 2004).

Despite strong support for the efficacy of CM during the active treatment phase, many professionals in the substance use treatment field question the durability of CM’s effect once reinforcers are discontinued (Petry et al., 2017; Rash et al., 2012, 2013). Some meta-analyses support this concern, finding that effect sizes decrease when reinforcers are discontinued (see Benishek et al., 2014, k = 19, 42% overlap [i.e., 42% of the studies in this meta-analysis are also included in the current review]; see Prendergast et al., 2006, k = 47, 4% overlap with current review; Sayegh et al., 2017, k = 35 CM studies, 31% overlap with current review). However, a recent systematic review reported nearly one third of CM studies (across all drug and reinforcer types) evidenced significant reductions in drug use after cessation of reinforcers (Davis et al., 2016, k = 69, 9% overlap with current review).

Our understanding of the long-term efficacy of substance use disorder treatments, including CM, may be heavily impacted by variation in outcome measures. No single metric for substance use treatment outcomes exists (Carroll et al., 2014; Donovan et al., 2012; Korte et al., 2011; Tiffany et al., 2012). Objective indices (i.e., biological measures based on urine toxicology screens) remove the risk of bias inherent in self-report (Del Boca & Noll, 2000; Hjorthøj et al., 2012; Magura & Kang, 1996; Schuler et al., 2009). However, most reviews of psychosocial treatments for substance use disorders focus on self-reported drug use (Dutra et al., 2008; Prendergast et al., 2006) or include objective biologically verified outcomes mixed in with studies that only provide self-report (e.g., self-reported frequency of use) and/or randomly biologically verified self-report outcomes (e.g., participants are told they could be drug tested to verify self-report; Benishek et al., 2014; Sayegh et al., 2017).

Past meta-analytic reviews have provided strong evidence of CM’s efficacy during treatment and immediately posttreatment (Ainscough et al., 2017, k = 22, 9% overlap with current review; Dutra et al., 2008, k = 14 CM studies, 21% overlap with current review; Griffith et al., 2000, k = 30, 3% overlap with current review). Some meta-analyses have reported on longer term outcomes (Benishek et al., 2014; Prendergast et al., 2006; Sayegh et al., 2017), but these past reviews were limited because they either did not report biological outcomes (Prendergast et al., 2006) or they combined biologically verified outcomes with self-report and/or randomly biologically verified self-report outcomes (Benishek et al., 2014; Sayegh et al., 2017). Further, many reviews of CM focus on its efficacy when applied to only a single drug of abuse (e.g., cocaine, Farronato et al., 2013, k = 8, 38% overlap with current review; nicotine, Notley et al., 2019, k = 33, 0% overlap with current review) or do not comprehensively consider samples recruited from outpatient settings as well as medication assisted treatment clinics (Benishek et al., 2014). Additionally, no reviews that included long-term outcomes examined how critical CM parameters found to influence efficacy during the active treatment phase (i.e., frequency, immediacy, escalation, fading, magnitude of reinforcement, and form of CM; e.g., prize-based CM, Benishek et al., 2014 or voucher-based CM, Higgins et al., 2019) moderated efficacy after the discontinuation of reinforcers.

The current systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy of CM up to 1 year after the reinforcer delivery ended using objectively verified substance use treatment outcomes (i.e., urine drug screens). Only studies assessing outcomes following removal of the incentives were included in the present analyses. The overall aim of the study was to determine the relative efficacy of CM after reinforcers were discontinued compared with the long-term impact of other psychosocial treatment approaches in reducing substance use. The secondary aim was to understand critical moderators of the long-term efficacy of CM. This aim allows for an integrated evaluation of several variables only examined in isolation or collapsed, and possibly contributing to uncontrolled heterogeneity, in prior reviews (e.g., CM delivery method, single illicit drug of abuse). This study seeks to directly address prior criticism of CM’s lack of durable efficacy and includes comprehensive evaluation of factors that may enhance or detract from that efficacy.

Method

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they (a) evaluated the efficacy of CM for treating illicit stimulant, opioid, or polydrug use; (b) randomly assigned participants to two or more conditions; (c) enrolled at least 25 participants per condition (as recommended by Chambless & Hollon, 1998); (d) had at least one long-term follow-up (i.e., outcomes measured after the protocol treatment was ended and the initial response to treatment had been determined); (e) presented substance use outcomes based on urine toxicology; and (f) were published in English.

Studies were excluded if (a) 25% or more of enrolled participants were under 18 years of age (b) they presented secondary data from another trial included in the meta-analysis. When two studies presented data from the same trial, we chose the study with the largest sample size. Studies in which participants were recruited from a setting that provided medication assisted treatment (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine) were included if they evaluated CM’s efficacy for treating illicit substance use in that sample (e.g., CM to increase abstinence from stimulants in persons also receiving methadone for an opioid use disorder) but were excluded if the CM exclusively targeted a behavior other than abstinence, such as medication adherence.

Search Strategy

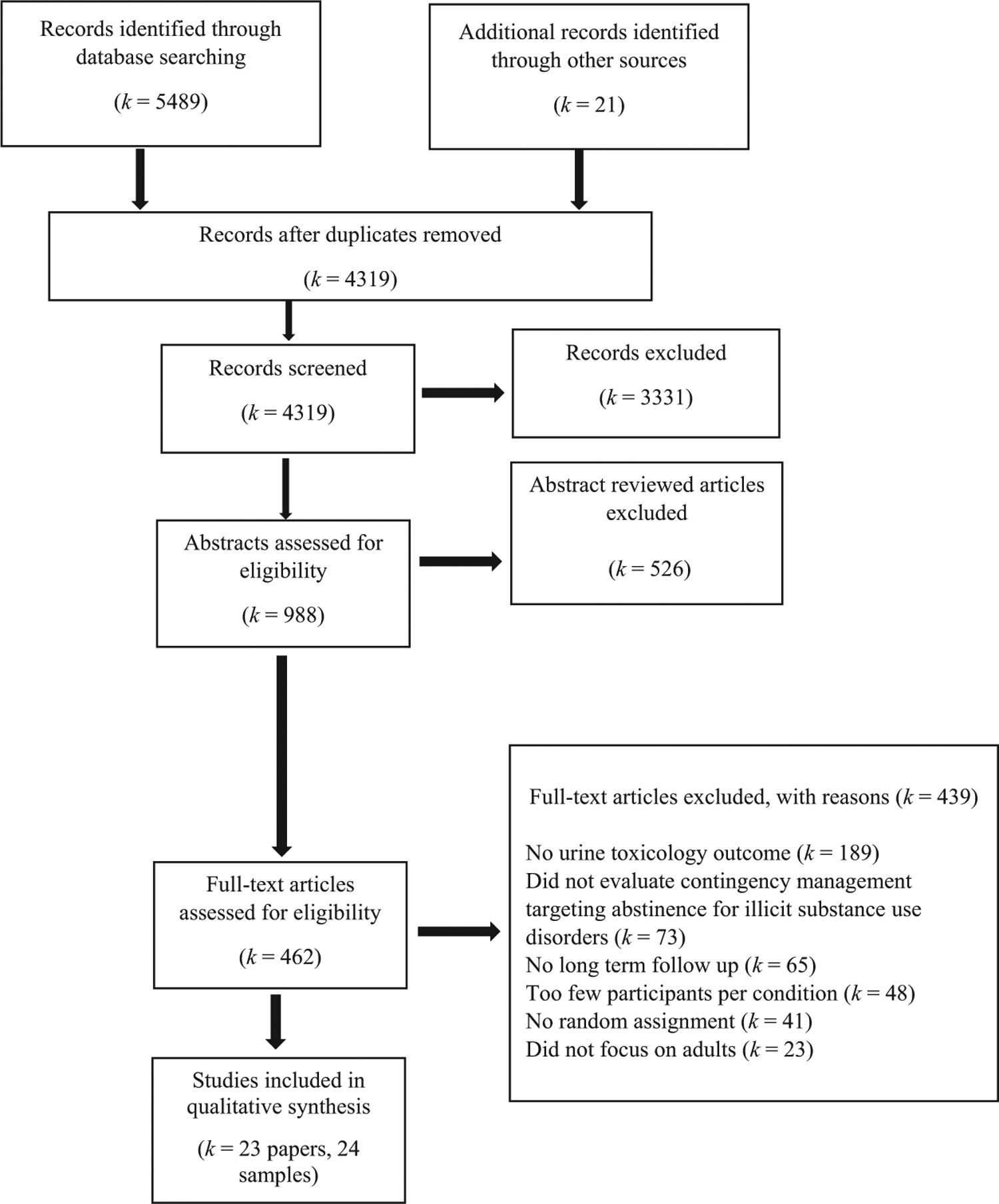

Studies published in any year through July 2020 were reviewed based on PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). Figure 1 provides a diagram of the implementation of these guidelines. Searches were performed in PubMed and PsycINFO using the following combination of search terms [“motivational interview*” or “motivational enhancement” or “motivation* intervention” or “contingency management” or “voucher” or “behavioral contracting” or “token economy” or “community reinforcement” or “matrix model” or “aftercare” or “relapse prevention” or “twelve step” or “12 step” or “twelve step facilitation” or “12 step facilitation” or “family thera*” or “family intervention*” or “couples thera*” or “couples intervention” or “seeking safety” or “mindful*”] AND [“randomize*” or “random” or “randomly” or “clinical trial” or “control* trial”] AND [“substance*” or “drug*” or “cocaine” or “crack” or “stimulant” or “amphetamine” or “methamphetamine” or “heroin” or “opiate*” or “opioid” or “marijuana” or “cannabis”]. Search terms included the names of evidence-based treatments besides CM to ensure inclusion of all studies with CM as the comparator. Additionally, we searched: 1) reference lists of CM review articles identified using the search terms (k = 17); 2) CM review articles identified in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (k = 5), and 3) reference lists of studies that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria (k = 23) to ensure we included all relevant studies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Records Identified and Reviewed

Screening Abstracts

Titles and abstracts captured by the search strategy were screened in a multistep process. One author imported all identified records into reference management software (Mendeley Desktop, 2017, Mendeley Ltd., New York). Confirmed duplicates were deleted, and the remaining records were screened individually. Clearly nonrelevant records (e.g., relapse prevention for a physical health condition, smoking studies) were removed, as were records for which abstracts indicated the paper would not meet inclusion criteria (e.g., small sample, nonrandom assignment). Articles for which the abstract appeared to meet inclusion, or for which eligibility could not be determined, were moved to full-text review. One author independently conducted full-text review to determine inclusion of studies. Two additional authors completed a second full-text review on a randomly selected sample of one third of the 439 excluded articles as well as 100% of studies classified by the first reviewer as meeting inclusion but not exclusion criteria. Reviewers used a codebook for making inclusion/exclusion decisions. Interrater percentage agreement overall for inclusion and exclusion of articles was 97% (k = 0.88). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus, and when needed, discussion with a third reviewer. For complete list of excluded studies see online supplemental materials for details.

Data Extraction

The primary outcome extracted from each study was urine toxicology results at the longest available follow-up, which were either the percentage of negative urine toxicology results (i.e., the number of negative urines samples provided as a ratio to the total number of urine samples provided over the duration of the follow-up period with samples collected at several time points) or the point prevalence rates of abstinence (i.e., whether a urine sample was negative for a target drug at the single time point of the follow-up assessment). If both outcomes were available, percentage of negative urine toxicology was prioritized for extraction, because this outcome is more predictive of long-term outcomes (Preston et al., 1998; Stitzer et al., 2009). If a study had multiple follow-up periods, results from the latest follow-up were reported. Results from intent-to-treat samples were extracted whenever they were available. If the study did not use intent-to-treat analyses, coders adjusted urine toxicology results with missing data assumed positive (for k = 6 studies, seven samples). If data were missing such that calculations using intent-to-treat analyses were not possible, authors were contacted directly with a 100% response rate (k = 2; Chudzynski et al., 2015; Petry et al., 2015). Intent-to-treat calculations and author correspondence allowed for inclusion of all studies identified by our search in the calculations of overall odds ratios (ORs) described in the following text.

In addition to the primary outcome variable, we extracted number of study, participant, and CM treatment variables. The study variables were publication year, comparison condition (nonspecific therapy, community-based comprehensive therapy, protocol-focused specific therapy; see next paragraph for further information about comparison condition categories), targeted drug (stimulants only, opioids only, or polysubstance use), whether study recruitment was conducted in a medication assisted treatment clinic (yes/no), outcome type (percentage of negative urine samples or point prevalence of abstinence), and when long-term drug use outcomes were evaluated since discontinuation of CM, measured in weeks. Participant variables were demographic characteristics such as mean age, the percentage identifying as female, and the percentage identifying as White. The CM treatment variables were (a) escalation, that is, participants could earn rewards of escalating value for consecutive negative urine toxicology samples (yes/no); (b) fading, that is, a design feature where reinforcers are reduced or become more variable over time (faded vs. not faded); (c) frequency (the number of times reinforcement was earned per week); (d) immediacy (immediate reinforcement delivery vs. delayed); (e) maximum reinforcer magnitude available in average number of dollars available per participant; (f) CM delivery method (prize vs. voucher); and (g) the duration of the CM protocol measured in weeks.

Comparison conditions were grouped into nonspecific therapy, community-based comprehensive therapy, or protocol-focused specific therapy. Nonspecific therapies included “treatment as usual” or “standard care” where participants had assistance from providers related to substance use treatment, mental health care, and other psychosocial needs but it was on an infrequently/unstructured basis (≲1 time per week). Community-based comprehensive therapy included structured programs of care with more frequent contacts (e.g., intensive outpatient substance use treatment). Comparison conditions were denoted as protocol-focused specific therapies when the studies employed a specific recognized and/or manualized efficacious substance use treatment (e.g., cognitive–behavioral therapy, 12-step facilitation).

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was used to assess for possible bias in the included studies (Higgins & Green, 2011). The following four criteria were assessed: random assignment, allocation concealment, masking of outcome assessors, and incomplete outcome data. Selective outcome reporting was not rated because most psychosocial treatment trials are still not prospectively registered (Bradley et al., 2017). Each risk of bias criterion was designated as high, low, or unclear risk of bias. We computed overall quality for each study; studies with three or more indicators of low risk of bias were designated high quality, and studies with two or fewer indicators of low risk were designated low quality.

For each study included in the final review, at least two authors extracted data using a standardized form. A third author independently extracted data from a randomly selected third of studies to ensure three-way reliability. Interrater agreement for data extraction was 96%, and differences were resolved through consensus or review by a third coder when necessary.

Analytic Plan

Descriptive data are provided for each study individually, with each study grouped by whether participants were receiving medication assisted treatment (see Table 1). All statistical analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis v3.3070. ORs, which represented the likelihood of a participant who received CM achieving abstinence over a participant who received a comparison treatment, were calculated for each treatment comparison group across the 23 studies with respect to urine toxicology outcomes. If studies contained multiple CM groups compared with one control comparison, then the OR effect sizes were combined and averaged into one OR effect size. Effect sizes were combined by aggregating binary data of positive and negative urine toxicology outcomes from the treatment groups and comparing the aggregated data to the positive and negative urine toxicology outcomes of the comparison condition (Borenstein et al., 2009). A one-study removed analysis was conducted to gauge the impact of each study on the overall ORs.

Table 1.

Description of Studies and Study Conditions Included in the Meta-Analysis on Contingency Management (CM)

| Study | N | Treatment condition (n) | Comparison condition (n) | CM duration | Prize (P) or voucher(V) | Escalation with reset | Fading | Frequency | Immediate reinforcers | Reinforcer magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants recruited from a setting other than a medication assisted treatment clinic | ||||||||||

| Alessi et al., 2007 | 103 | CM (46) | SC-IOP (57) | 12 weeks | P | Y | Y | 2 | Y | $248 |

| Chudzynski et al., 2015 | 119 | CM (30) | SC-Matrix (29) | 16 weeks | V | Y | N | 3 | Y | $1,155 |

| CM (32) | V | Y | N | N | ||||||

| CM (28) | V | Y | N | N | ||||||

| Hagedorn et al., 2013 | 141 | CM (71) | SC-IOP (70) | 8 weeks | V | Y | N | 2 | Y | $157 |

| Jones et al., 2005 | 130 | CM living expenses (66) | SC (64) | 12 weeks | V | N | Y | 7 | N | $2,294 |

| McDonell et al., 2013 | 176 | CM (91) | SC + NC prizes (85) | 12 weeks | P | Y | N | 3 | Y | $588 |

| Petry et al., 2005 | 142 | CM (53) | SC-IOP (38) | 12 weeks | V | Y | Y | 3 | Y | $456 |

| CM (51) | P | Y | Y | Y | $543 | |||||

| Petry et al., 2006 | 84 | CM (44) | SC-IOP (40) | 12 weeks | P | Y | Y | 3 | Y | $470 |

| Petry et al., 2010 | 170 | CM (89) | TSF + NC prizes (81) | 24 weeks | P | Y | N | 1 | Y | $400 |

| Petry et al., 2011 | 239 | CM (117) | SC-IOP (122) | 12 weeks | P | Y | N | 2 | Y | $462 |

| Petry, Barry, et al., 2012 | 109 | CM (35) | SC-IOP (34) | 12 weeks | P | Y | Y | 3 | Y | $250 |

| CM (40) | P | Y | Y | Y | $560 | |||||

| Petry, Barry, et al., 2012 second sample | 226 | CM (118) | SC-IOP (108) | 12 weeks | P | Y | Y | 3 | Y | $250 |

| Rawson et al., 2006 | 118 | CM (60) | CBT (58) | 16 weeks | V | Y | N | 3 | Y | $989 |

| Roll et al., 2006 | 113 | CM (51) | SC (62) | 12 weeks | P | Y | N | 2 | Y | $420 |

| Roll et al., 2013 | 118 | CM (29) | SC-Matrix (29) | 16 weeks | P | Y | N | 3 | Y | $250 |

| CM 2 month (30) | 8 weeks | Y | ||||||||

| CM 1 month (30) | 1 wk | Y | ||||||||

| Shoptaw et al., 2005 | 82 | CM (42) | CBT (40) | 16 weeks | V | Y | N | 3 | Y | $1,278 |

| Participants recruited from a medication assisted treatment clinic (all were methadone maintenance clinics) | ||||||||||

| Brooner et al., 2007 | 118 | CM (59) | SC (59) | 24 weeks | V | Y | N | 1 | Y | $3,201 |

| Epstein et al., 2003 | 96 | CM (47) | SC + NC vouchers (49) | 12 weeks | V | Y | N | 3 | Y | $1,155 |

| Iguchi et al., 1997 | 62 | CM (27) | SC (35) | 12 weeks | V | N | N | 3 | N | $180 |

| Peirce et al., 2006 | 388 | CM (190) | SC (198) | 12 weeks | P | Y | N | 2 | Y | $400 |

| Petry, Alessi, et al., 2012 | 130 | CM (71) | SC (59) | 12 weeks | P | Y | N | 3 | Y | $381 |

| Petry et al., 2015 | 240 | CM (63) | SC (57) | 12 weeks | V | Y | N | 3 | Y | $900 |

| CM (62) | P | Y | N | Y | $900 | |||||

| CM (58) | P | Y | N | Y | $300 | |||||

| Preston et al., 2002 | 110 | CM take home doses (55) | NC take home doses (55) | 12 weeks | V | N | N | 3 | N | $360 |

| Rawson et al., 2002 | 54 | CM (27) | SC (27) | 16 weeks | V | Y | N | 3 | Y | $1,278 |

| Silverman et al., 2004 | 52 | CM take home doses (26) | SC (26) | 52 weeks | V | Y | N | 3 | Y | $5,800 |

Note. Frequency refers to the maximum number of times that reinforcement could be earned per week. Reinforcement magnitude refers to the maximum monetary value that could be earned per participant during treatment. CBT = cognitive-behavioral therapy; SC = standard care or treatment as usual; IOP = intensive outpatient treatment; Y = yes; N = no; NC = noncontingent incentives; TSF = 12-step facilitation.

Calculations used natural log transformations of the OR with inverse variance weighting to account for differences in sample sizes across studies. Results were then converted back to ORs via inverse natural log transformations (Bland & Altman, 2000; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Studies were expected to be at least moderately heterogeneous given the differing lengths of follow-up periods and different target drugs, with variability not solely due to sampling error. As such, overall ORs were calculated using random effects models (Neyeloff et al., 2012). Cochran’s Q statistic estimated heterogeneity in effect sizes, and the inconsistency index (I2) was reported as an estimate of variance due to heterogeneity (Higgins et al., 2003; Neyeloff et al., 2012).

Multiple tests were conducted to test for possible publication bias, including the examination of a funnel plot, the Egger regression test for asymmetry (Egger et al., 1997), and calculation of the fail-safe N (Rosenthal, 1979). An asymmetrical funnel plot indicates publication bias. The Egger test uses linear regression to assess the relation between error and study effect sizes. A fail-safe N determines the number of nonsignificant studies not identified by a review that would be needed for a significant OR to no longer be significant (Rosenthal, 1979).

We explored 18 possible moderators of CM efficacy (see Tables 1 and 2) at long-term follow up. Metaregressions were conducted to test for potential moderators with long-term outcomes where the log OR effect sizes were regressed onto continuous variables detailed in the data extraction section. Subgroup analyses tested for differences in long-term outcomes based on the categorical variables detailed in the data extraction section. Subgroup analyses were conducted using a mixed effects model, and significance was tested with the fixed effects model. Variables were only tested as moderators if there were at least 10 studies reporting sufficient statistical information (Higgins & Green, 2011). One-study removed analyses were conducted to gauge the impact of each study moderator on the findings from metaregressions and subgroup analyses (Borenstein et al., 2013).

Table 2.

Design Features of Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis and Assessment of Their Study Quality

| Study | Drug | Comparison condition | Long-term outcome type (weeks since CM discontinuation) | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of outcome assessors | Complete data | Overall study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants recruited from a setting other than a medication assisted treatment clinic | ||||||||

| Alessi et al., 2007 | S | CBCT | PP (24) | ? | ? | + | + | − |

| Chudzynski et al., 2015 | S | CBCT | %neg (1 – 12) | ? | ? | + | − | − |

| Hagedorn et al., 2013 | S | CBCT | PP (46) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Jones et al., 2005 | P | NST | PP (40) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| McDonell et al., 2013 | S | NST | PP (12) | + | ? | + | − | − |

| Petry et al., 2005 | S | CBCT | $PP (24) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Petry et al., 2006 | P | CBCT | PP (24) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Petry et al., 2010 | P | PFST | PP (28) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Petry et al., 2011 | P | CBCT | PP (40) | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Petry, Barry, et al., 2012 | S | CBCT | %neg (20 – 24) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Petry, Barry, et al., 2012 second sample | S | CBCT | %neg (20 – 24) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Rawson et al., 2006 | S | PFST | PP (36) | + | ? | + | ? | − |

| Roll et al., 2006 | S | NST | %neg (12 + 24) | 7 | ? | + | − | − |

| Roll et al., 2013 | S | CBCT | %neg (1 – 16) | 7 | ? | + | − | − |

| Shoptaw et al., 2005 | S | PFST | PP (36) | + | ? | − | − | + |

| Participants recruited from a medication assisted treatment clinic (all methadone) | ||||||||

| Brooner et al., 2007 | P | NST | %neg (1 – 12) | ? | ? | + | + | − |

| Epstein et al., 2003 | S | NST | %neg (1 – 26) | ? | ? | + | + | − |

| Iguchi et al., 1997 | P | NST | %neg (1 – 6) | ? | ? | + | ? | − |

| Peirce et al., 2006 | P | NST | PP (12) | + | + | + | − | + |

| Petry, Alessi, et al., 2012 | S | NST | PP (24) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Petry et al., 2015 | S | NST | PP (40) | + | ? | + | − | − |

| Preston et al., 2002 | O | NST | PP (52) | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Rawson et al., 2002 | S | NST | %neg (1 – 26) | ? | ? | + | ? | − |

| Silverman et al., 2004 | S | NST | %neg (1 – 9) | + | ? | + | + | + |

Note. Plus signs indicate low risk of bias/high study quality; minus signs indicate high risk of bias/low study quality; and questions marks indicate that the risk of bias is unclear. CM = contingency management; S = stimulants; CBCT = community-based comprehensive therapy; PP = point prevalence rates of abstinence; %neg = percentage of submitted urine samples that were negative; P = polysubstance use; NST = nonspecific therapy; PFST = protocol focused specific therapy; O = opioids.

Results

The search yielded 5,510 records, which led to the identification of 23 independent studies (see Figure 1 for the complete details of the search). Table 1 displays the 23 studies with 24 CM treatment-to comparison treatment contrasts at long-term follow-up along with the design features of the CM treatment conditions.

Across the 23 studies, a total of 3,320 participants were allocated to study conditions. All studies were conducted in the United States of America. Publication dates ranged from 1997 to 2015. Sample sizes across the 23 studies ranged from 52 to 388 (M = 138.3, SD = 74.2, Mdn = 118.0). The mean age of participants was 39.1 (SD = 5.8, Mdn = 37.6). Approximately 42.1% (SD = 15.7, Mdn = 44.1) of the sample identified as female, and 45.2% (SD = 20.5, Mdn = 46.4) identified as White. Of the 23 studies, 38% included a sample of participants recruited from a medication assisted treatment clinic (100% of which were methadone clinics, but substances targeted by CM in these studies varied, see Table 2 for more details).

Of the 32 CM treatments, approximately 53% provided prize-based CM and 47% used the voucher method. Almost all treatments utilized escalating reinforcers (91%) that were delivered immediately (84%) upon submission of a negative urine screen. Few treatments (25%) utilized a reinforcement schedule that faded over time. The frequency of reinforcement that could be earned per week ranged from 1 and 7. The average maximum magnitude of reinforcement available per participant per treatment episode was $914.46 (Mdn = $466.0). Table 2 displays the primary drug that participants used, the type of comparison group, how the urinalysis outcome was reported (point prevalence vs. percent negative), when the long-term follow-up occurred relative to when CM was discontinued, and the risk of bias assessment for each study criterion. Most studies examined the effect of CM on stimulant use only (67%), followed by polysubstance use (29%) and opioid use only (4%). Slightly more than half the studies (54%) utilized nonspecific therapy comparison groups, 33% used community-based nonspecific comprehensive therapies, and 13% utilized protocol-focused specific treatments. At long-term follow-up, about 58% of studies examined the point prevalence of abstinence and 42% the percentage of negative urine samples submitted over the follow-up period. These outcomes were assessed between 6 and 52 weeks (Mdn = 24.0) after CM was discontinued.

Results of the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool indicated 54% of the studies were designated high quality and about 46% were low quality. Approximately two thirds (67%) of studies provided an adequately detailed description of the method used to generate a random sequence (e.g., used a computer program or a random table of numbers) and about 33% did not (e.g., simply stated participants were “randomized” with no further description of procedures). One study (4%) described an adequate method to conceal the allocation of participants to conditions from study investigators, while the remaining studies described no method to conceal allocation. All (100%) studies were determined to have adequate masking of assessors, as they used the objective assessment of urine toxicology to assess abstinence from drug use. Approximately 62% of studies reported appropriate procedures to analyze outcome data (e.g., no missing outcome data) and about 38% did not (e.g., completer analysis; imputed outcomes).

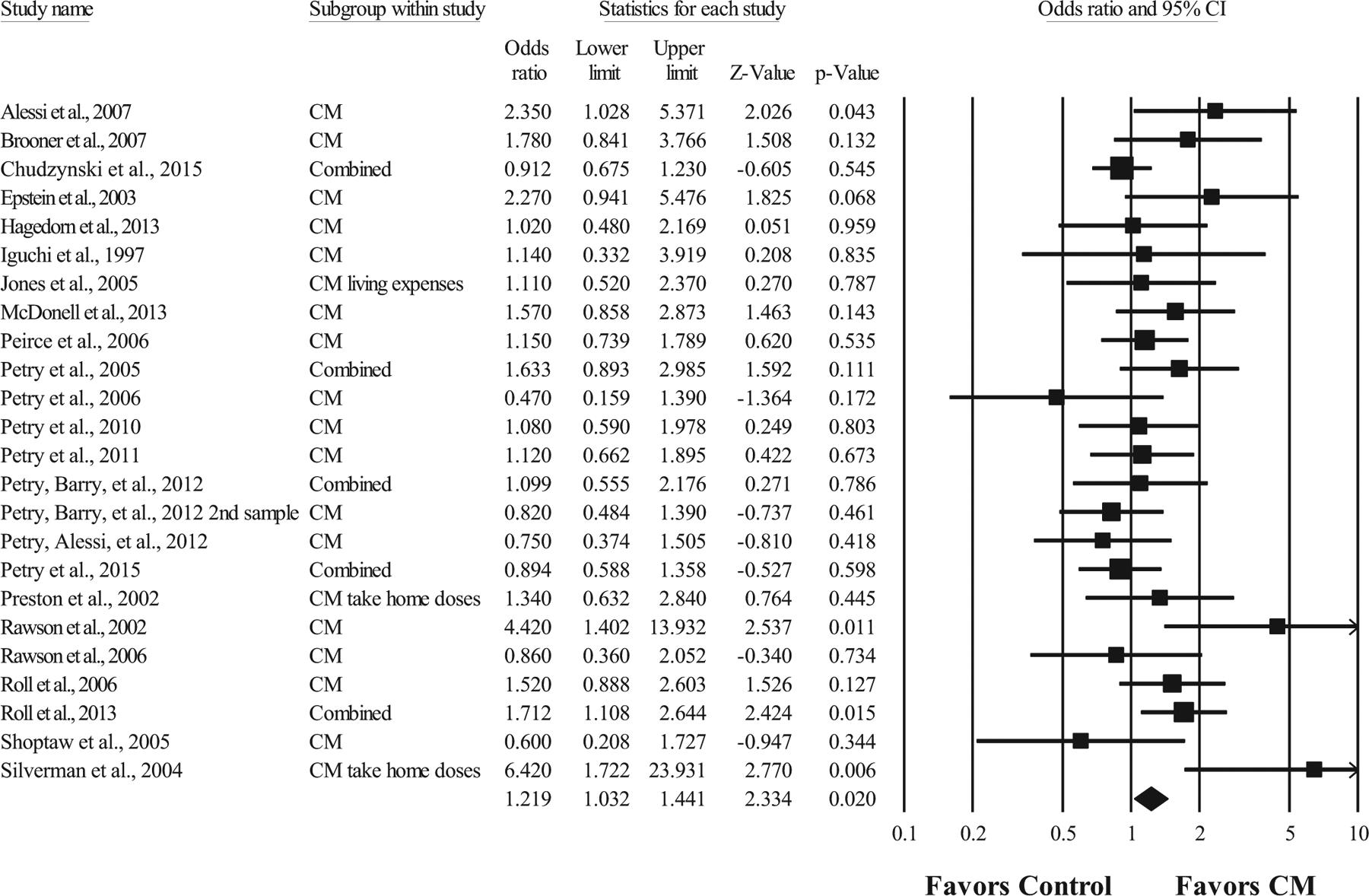

Long-Term Outcomes

Figure 2 displays a forest plot of the overall OR effect size of each study at long-term follow-up and the weighted average OR effect size. At long-term follow-up, the weighted average OR effect size was 1.22, 95% confidence interval [1.03, 1.44], p = .02 (k = 23), with low to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 36.68). The one study removed analysis resulted in ORs ranging from 1.18 to 1.26, indicating that the results were not highly influenced by any single study. This weighted effect size indicates that participants who received CM were 1.22 times more likely to be abstinent based on urinalysis at follow-ups occurring after (Mdn = 24 weeks) discontinuation of the incentive delivery than participants who received a nonspecific therapy, a nonspecific comprehensive therapy, or a specific therapy comparison condition. The funnel plot of the OR effect sizes was symmetrical, and the Egger’s regression test did not indicate publication bias (p > .05). The fail-safe N indicated that 37 unpublished studies with nonsignificant results would be necessary to reduce this result to a nonsignificant level.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Effect Sizes for Contingency Management Treatment Versus Comparison Conditions at Long-Term Follow-Up.

Note. Values are truncated after the third decimal point. The last row in the forest plot represents the overall odds ratio effect size of all studies. “Combined” indicates a study with multiple contingency management (CM) conditions that were summarized into one odds ratio effect size.

Moderators of Long-Term Outcome

We explored 18 possible moderators of CM’s long-term efficacy. Metaregressions tested the possible moderating effect of several participant demographics, publication year, reinforcer magnitude, the number of weeks elapsed since the discontinuation of CM, and the duration of the CM protocol (see Table 3). There were significant moderating effects of publication year and treatment duration on CM outcomes up to 1 year after the discontinuation of reinforcers. The metaregressions indicated a 1-year increase in publication year was associated with a 0.04 decrease in the log OR (p = .04, k = 23). For treatment duration, a one week increase in the duration of CM was associated with a 0.03 increase in the log OR (p = .04, k = 23). The log OR effect size also increased as reinforcer magnitude increased (p = .05, k = 23). However, for reinforcer magnitude, a one study removed analysis indicated the relation appeared mostly driven by one study (i.e., Silverman et al., 2004) and became nonsignificant when that study was removed from the metaregression (p = .59, k = 22). Subgroup analyses tested the moderating effects of several categorical variables (see Table 4). No other moderators were significant, including the CM delivery method (i.e., prize vs. vouchers) and CM parameters (i.e., escalating, fading, and immediacy; all ps > .05); however, this might be due to homogeneity in the types of CM treatments examined in this meta-analysis, as many utilized similar reinforcement schedules.

Table 3.

Results From Metaregressions of Several Possible Moderators With Contingency Management Outcomes up to 1 Year Following Treatment

| Moderator (k) | Point estimate | 95% CI | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant age (24) | ||||

| Slope | 0.00 | [−0.03, 0.03] | 0.06 | .95 |

| Intercept | 0.16 | [−1.02, 1.34] | 0.27 | .78 |

| Participant gender: Percentage female (24) | ||||

| Slope | 0.01 | [−0.00, 0.02] | 1.23 | .22 |

| Intercept | −0.14 | [−0.70, 0.42] | −0.49 | .63 |

| Participant race: Percentage White (21) | ||||

| Slope | −0.01 | [−0.02, 0.00J | −1.11 | .26 |

| Intercept | 0.48 | [−0.07, 1.03] | 1.70 | .09 |

| Publication year (24) | ||||

| Slope | −0.04 | [−0.07, −0.00] | −2.03 | .04 |

| Intercept | 73.52 | [2.88, 144.17] | 2.04 | .04 |

| Reinforcer frequency (24) | ||||

| Slope | −0.02 | [−0.19, 0.14] | −0.29 | .77 |

| Intercept | 0.27 | [−0.20, 0.74] | 1.11 | .27 |

| Reinforcer magnitude (24) | ||||

| Slope | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.00] | 1.98 | .05 |

| Intercept | 0.06 | [−0.19,0.30] | 0.44 | .66 |

| Time of follow-up in weeks (24) | ||||

| Slope | −0.01 | [−0.02, 0.01] | −1.22 | .22 |

| Intercept | 0.42 | [0.02, 0.82] | 2.08 | .04 |

| Treatment duration (24) | ||||

| Slope | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.06] | 2.05 | .04 |

| Intercept | −0.25 | [−0.68,0.18] | −1.14 | .25 |

Note. Point estimates reflect the amount of increase or decrease in the log odds ratio effect sizes. k = number of studies; CI = confidence interval.

Table 4.

Results From Subgroup Analyses of Several Possible Moderating Variables With Contingency Management Outcomes up to 1 Year Following Treatment

| Moderator (k) | OR | 95% CI | Q | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control condition (24) | 2.79 | .25 | ||

| Nonspecific therapy (9) | 1.15 | [0.90, 1.48] | ||

| Community-based comprehensive therapy (12) | 1.40 | [1.07, 1.83] | ||

| Protocol-focused specific therapy (3) | 0.91 | [0.58, 1.43] | ||

| Escalating reinforcers (24) | 0.00 | .95 | ||

| No (3) | 1.21 | [0.74, 1.97] | ||

| Yes (21) | 1.23 | [1.02, 1.48] | ||

| Fading reinforcers (24) | 0.15 | .70 | ||

| No (18) | 1.24 | [1.03, 1.51] | ||

| Yes (6) | 1.14 | [0.78, 1.67] | ||

| Immediate reinforcers (32) | 1.03 | .31 | ||

| No (5) | 1.00 | [0.69, 1.46] | ||

| Yes (27) | 1.24 | [1.05, 1.48] | ||

| Outcome type (24) | 2.57 | .11 | ||

| Percentage of negative samples (10) | 1.49 | [1.08, 2.06] | ||

| Point prevalence (14) | 1.10 | [0.93, 1.31] | ||

| Study recruitment at a methadone treatment clinic (24) | 1.19 | .28 | ||

| No (15) | 1.16 | [0.97, 1.38] | ||

| Yes (9) | 1.46 | [1.00,2.11] | ||

| Study quality (24) | 2.45 | .12 | ||

| High (13) | 1.08 | [0.88, 1.33] | ||

| Low (11) | 1.41 | [1.08, 1.84] | ||

| Time of follow-up in weeks (24) | 0.40 | .52 | ||

| <3 months (6) | 1.37 | [0.93, 2.00] | ||

| 3 to 12 months (18) | 1.19 | [0.98, 1.44] | ||

| Type of drug (24) | 0.06 | .97 | ||

| Opioids (1) | 1.34 | [0.63, 2.84] | ||

| Stimulants (15) | 1.22 | [0.98, 1.51] | ||

| Polysubstance use (8) | 1.22 | [0.89, 1.67] | ||

| Type of reinforcer (32) | 0.40 | .53 | ||

| Prize (17) | 1.16 | [0.98, 1.38] | ||

| Voucher (15) | 1.29 | [0.97, 1.73] |

Note. k = number of studies; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

Objective assessment of long-term outcomes is relatively uncommon in clinical trials for substance use treatments. This meta-analysis included 23 randomized trials of CM that had large (>25/condition) samples of adult participants and reported urine toxicology results at long-term follow-ups. This study focused specifically on CM, a psychosocial treatment model with strong efficacy for reducing substance use during the active treatment period (Dutra et al., 2008) that has faced skepticism about its durability (Petry et al., 2017). Despite this criticism, the overall OR for CM at long-term follow up was significant, and participants who received CM evidenced a 22% greater likelihood of abstinence at a median of 24 weeks after reinforcement ended than participants receiving comparison treatments. These results provide support of lasting benefits of CM after reinforcers have been discontinued using objective indices of drug use outcomes.

CM was found to be equally efficacious in the long-term regardless of participant age, race, or gender. Length of follow-up, engagement of participants in medication assisted treatment, type of comparison condition, drug(s) used, outcome type, and study quality did not significantly moderate CM efficacy at long-term follow-up. Study publication year was found to relate to a significant decrease the efficacy of CM, with newer studies showing smaller effect sizes. Additionally, longer treatment duration was associated with better long-term outcomes. Longer treatment duration may allow for greater opportunity to establish durations of continuous abstinence, a metric which has been consistently associated with better long-term outcomes (Preston et al., 1998; Stitzer et al., 2009). Type of reinforcement (chance to win prizes vs. vouchers for each negative drug screen) did not impact long-term outcomes, providing further support for the efficacy of both CM approaches (Petry et al., 2005; Petry et al., 2015).

Clinical Applications

CM’s costs are one of the foremost barriers to CM adoption (e.g., Benishek et al., 2010; Kirby et al., 2006; Rash et al., 2012, 2013), and costs are often directly related to the duration of CM treatment (i.e., longer CM protocols increase costs). Clinics will struggle to implement CM with fidelity without external support to fund CM, which is especially important considering findings that CM is no more effective than standard care when reinforcement magnitude drops below certain levels (Petry et al., 2004). To be effective, CM’s “dose” must be in the effective range, and a significant proportion of addiction treatment providers in community settings report maximum available reinforcement per patient well below effective “doses” (Rash et al., 2013, 2020). The Veterans Affairs’ national implementation of CM in its IOP programs provides a model of successful adoption and sustainment of CM programs that maintained fidelity, including to parameters such as magnitude and duration (DePhilippis et al., 2018; Petry et al., 2014; Rash & DePhilippis, 2019). Outside the Veterans Affairs, new pathways to fund CM by payers (i.e., reimbursement) have yet to be made available despite CM’s clear evidence of efficacy relative to other commonly used psychosocial treatments (e.g., CBT, MI, relapse prevention; Dutra et al., 2008; Petry et al., 2017). These funding issues represent critical barriers to the accessibility of CM that not only affect patients, but also limit potential societal benefits of successful substance use disorder treatment in the form of improved employment and productivity indices, reduced criminal activity, reduced risk behavior and spread of disease, and improved family functioning (Petry et al., 2017). Despite these barriers, CM has some distinct advantages beyond its clinical superiority. It can be integrated with wide variety of platform therapies; it works with most client populations; and it can be readily adapted to clinic and client needs. Further, both clinical and nonclinical staff can be trained to deliver CM, which may open additional options for accessing treatment in nontraditional settings (e.g., housing programs, employment programs) if funding barriers are resolved.

Long-Term Benefits

Long-term benefits were significant compared with comparison treatments even though many of the trials contained design features that could have reduced the likelihood of uncovering between-groups differences. Notably, 13% of CM trials employed a treatment comparison that was itself a specific protocol-based evidence-based treatment (e.g., cognitive–behavioral therapy), and 33% of “standard care” conditions were intensive outpatient treatment. Thus, many participants, not only those in active CM, were engaged in robust, high intensity treatment and likely received many of the indirect and often unmeasurable benefits of psychotherapy treatment (Wampold, 2015). Effect sizes are larger when “passive” or no or minimal comparison conditions are used relative to “active” and attention-matched comparison conditions (Prendergast et al., 2006), yet this meta-analysis found benefits of CM even with rigorous interventions as comparators. Further, effect sizes of CM were not significantly different for participants who were or were not on medication assisted treatment. This finding suggests that CM can be equally effective for those recruited from a medication-assisted treatment, a result that may become even more salient as public health efforts seek to increase capacity for individuals to access medication-based addiction treatments (Jones et al., 2015).

Despite the heterogeneity in effect sizes at long-term follow up, few clinical moderators were significant. However, prior research indicates that several CM parameters are significantly associated with enhanced efficacy of CM, including immediacy of reinforcement (Griffith et al., 2000; Lussier et al., 2006), frequency of reinforcement (Griffith et al., 2000), and escalation of reinforcement magnitude (Roll et al., 1996). We suspect that some of these null effects are driven by the high-quality designs used in most included studies, resulting in little heterogeneity in these CM parameters.

Limitations

Limitations include those common to all meta-analyses, such as publication bias. However, we set rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria, only included randomized trials reporting objective indices of drug use and conducted risk of bias assessment to increase confidence in the results. No evidence of publication bias was found across multiple metrics (i.e., examination of funnel plots, the Egger’s regression test, and the calculation of the Fail-safe N). Additionally, some statistical tests of moderators may have resulted in nonsignificant results due to lack of power. For example, several CM parameters (e.g., immediate and escalating reinforcers; Lussier et al., 2006; Roll et al., 1996) known to enhance abstinence were not significantly associated with long-term outcomes in the present meta-analysis. This may be due to few included studies utilizing CM protocols with delayed and nonescalating reinforcers. Collectively, these measures constitute an improvement on past studies, especially those utilizing participant self-report of drug abstinence.

Focusing on long-term outcomes led to the removal of studies without objective indices of drug use at follow-ups. To create variables of meaningful moderators with groupings large enough to analyze, some of the nuances of specific study variables may have been lost and may contribute to unmeasured heterogeneity in the analyses. For example, polysubstance was used as an overall label for studies assessing abstinence from more than one drug, but the number and types of drugs covered by this classification ranged widely by study. We also could not examine the influence of other key variables, such as comorbid mental health diagnoses, because few studies reported sufficient details. Finally, the median length of follow-up was only about 6 months after treatment ended and, given the chronic nature of substance use disorders, it will be important for future studies to utilize longer follow-up periods.

Urine toxicology provides an objective index of substance use, but it is not without limitations. First, most urine toxicology tests only capture drug use in the few days preceding the sample collection. Though CM protocols are designed with this limitation in mind, follow-ups are often limited to a snapshot of abstinence. Second, sensitivity and specificity of toxicology tests vary by drug of abuse (Peace et al., 2000). The studies primarily assessed abstinence from stimulants or multiple substances concurrently. Persons with different drug use disorders may respond differentially to CM and other treatments. For example, those with multiple drug use disorders have more difficulties in achieving abstinence from all substances, resulting in lower overall effect sizes of treatments for polysubstance users (Dutra et al., 2008).

Although no method for measuring drug use outcomes is standard across studies (Carroll et al., 2014; Donovan et al., 2012; Tiffany et al., 2012), biological indices such as toxicology testing should be prioritized. In assessing outcomes for chronic medical conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, for example, most if not all studies include measurement of A1c levels and blood pressure; reliance on self-reports when objective indices are available is considered unacceptable in clinical trials targeting other medical conditions. The relatively small number of trials that included toxicology testing in this review underscores that evaluation of substance use disorders lags that of other chronic conditions. The lack of standardization of outcome measures is not limited to the evaluation of CM and may impact findings in other reviews evaluating long-term effects of cognitive–behavioral, relapse prevention, and other addiction treatments (Burke et al., 2003; Magill & Ray, 2009; Ray et al., 2020; Sayegh et al., 2017). To improve quality of research and, ultimately, treatment, researchers and clinicians should prioritize objective indices of drug use in evaluating both short- and long-term efficacy of treatment approaches.

Conclusion

Past meta-analytic reviews of CM established its efficacy for improving substance use outcomes during treatment and immediately posttreatment (Ainscough et al., 2017; Dutra et al., 2008; Griffith et al., 2000). In addition, several meta-analyses focused on the long-term impact of CM (Benishek et al., 2014; Prendergast et al., 2006; Sayegh et al., 2017) but were limited because they did not report objective biological outcomes (Prendergast et al., 2006), or they merged biologically verified outcomes with self-report and/or randomly biologically verified self-report outcomes (Benishek et al., 2014; Sayegh et al., 2017). Results of the current meta-analysis provide new information to the field. Specifically, focusing on urine toxicology results, this meta-analysis found a significant long-term effect for CM, directly addressing the common concern that the effects of CM disappear once reinforcers are no longer provided. Of note, other evidence-based psychosocial treatments for substance use disorders (e.g., cognitive–behavioral therapy; Magill et al., 2019) do not face this same level of criticism, yet none have demonstrated significant long-term effects when only objective indicators of substance use are examined (Burke et al., 2003; Magill & Ray, 2009; Magill et al., 2019). Further, the effect of CM was robust across a wide range of demographic and clinical moderators. Overall, CM increased odds of abstinence across multiple investigative teams, participant demographics, and drugs of abuse. Benefits of CM were present across rigorously designed trials, including those with comparison groups using established, active treatment elements (Magill & Ray, 2009; Magill et al., 2019). Patients with substance use disorders deserve access to treatments with the greatest evidence of efficacy, and private and public insurers and society should support such treatments (Petry et al., 2017; Rash et al., 2017; Roll et al., 2009). These results provide novel evidence that CM has long-term efficacy in reducing drug use. However, no insurer or public payer, other than the Department of Veterans Affairs (DePhilippis et al., 2018), presently covers costs of CM. It is time that other health care systems and policy support this efficacious psychosocial intervention.

Supplementary Material

What is the public health significance of this article?

This meta-analysis provides a summary of long-term outcomes of contingency management treatment using objective indices of drug use. Contingency management was found to be more efficacious than either standard care or other evidence-based approaches up to 1 year following the discontinuation of incentives.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the late Nancy Petry who assisted in conceptualizing this project and reviewed early versions of this article.

This project was supported by Grants K23DA034879, R01MD013550, P50DA09241, P50AA027055, R01DA047183, R01AA023502, and T32AA018108 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content of this project is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Footnotes

Supplemental materials: https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000552.supp

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

- Ainscough TS, McNeill A, Strang J, Calder R, & Brose LS (2017). Contingency management interventions for non-prescribed drug use during treatment for opiate addiction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178, 318–339. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Alessi SM, Hanson T, Wieners M, & Petry NM (2007). Low-cost contingency management in community clinics: Delivering incentives partially in group therapy. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 15(3), 293–300. 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, & McLellan AT (2012). Evolution of concept, but not action, in addiction treatment. Substance Use & Misuse, 47(8–9), 1041–1048. 10.3109/10826084.2012.663273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, Kirby KC, Matejkowski J, Clements NT, Seymour BL, & Festinger DS (2014). Prize-based contingency management for the treatment of substance abusers: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 109(9), 1426–1436. 10.1111/add.12589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benishek LA, Kirby KC, Dugosh KL, & Padovano A (2010). Beliefs about the empirical support of drug abuse treatment interventions: A survey of outpatient treatment providers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 107(2–3), 202–208. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, & Altman DG (2000). The odds ratio. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 320(7247), 1468. 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, & Rothstein HR (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Multiple comparisons within a study (pp. 239–242). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, & Rothstein H (2013). Comprehensive meta-analysis, Version 3. Biostat. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley HA, Rucklidge JJ, & Mulder RT (2017). A systematic review of trial registration and selective outcome reporting in psychotherapy randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135(1), 65–77. 10.1111/acps.12647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brooner RK, Kidorf MS, King VL, Stoller KB, Neufeld KJ, & Kolodner K (2007). Comparing adaptive stepped care and monetary-based voucher interventions for opioid dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(2), S14–S23. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, & Menchola M (2003). The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(5), 843–861. 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Kiluk BD, Nich C, DeVito EE, Decker S, LaPaglia D, Duffey D, Babuscio TA, & Ball SA (2014). Toward empirical identification of a clinically meaningful indicator of treatment outcome: Features of candidate indicators and evaluation of sensitivity to treatment effects and relationship to one year follow up cocaine use outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 137, 3–19. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, & Hollon SD (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 7–18. 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Chudzynski J, Roll JM, McPherson S, Cameron JM, & Howell DN (2015). Reinforcement schedule effects on long-term behavior change. The Psychological Record, 65(2), 347–353. 10.1007/s40732-014-0110-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DR, Kurti AN, Skelly JM, Redner R, White TJ, & Higgins ST (2016). A review of the literature on contingency management in the treatment of substance use disorders, 2009–2014. Preventive Medicine, 92, 36–46. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, & Noll JA (2000). Truth or consequences: The validity of self-report data in health services research on addictions. Addiction, 95(Suppl. 3), 347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePhilippis D, Petry NM, Bonn-Miller MO, Rosenbach SB, & McKay JR (2018). The national implementation of contingency management (CM) in the Department of Veterans Affairs: Attendance at CM sessions and substance use outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 185, 367–373. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Bigelow GE, Brigham GS, Carroll KM, Cohen AJ, Gardin JG, Hamilton JA, Huestis MA, Hughes JR, Lindblad R, Marlatt GA, Preston KL, Selzer JA, Somoza EC, Wakim PG, & Wells EA (2012). Primary outcome indices in illicit drug dependence treatment research: Systematic approach to selection and measurement of drug use end points in clinical trials. Addiction, 107(4), 694–708. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03473.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, & Otto MW (2008). A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(2), 179–187. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, & Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal, 315, 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Epstein DH, Hawkins WE, Covi L, Umbricht A, & Preston KL (2003). Cognitive-behavioral therapy plus contingency management for cocaine use: Findings during treatment and across 12-month follow-up. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(1), 73–82. 10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farronato NS, Dürsteler-MacFarland KM, Wiesbeck GA, & Petitjean SA (2013). A systematic review comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy and contingency management for cocaine dependence. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 32(3), 274–287. 10.1080/10550887.2013.824328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Rowan-Szal GA, Roark RR, & Simpson DD (2000). Contingency management in outpatient methadone treatment: A meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 58(1–2), 55–66. 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00068-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hagedorn HJ, Noorbaloochi S, Simon AB, Bangerter A, Stitzer ML, Stetler CB, & Kivlahan D (2013). Rewarding early abstinence in Veterans Health Administration addiction clinics. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(1), 109–117. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeck DM, Hser YI, & Teruya C (2008). Empirically supported substance abuse treatment approaches: A survey of treatment providers’ perspectives and practices. Addictive Behaviors, 33(5), 699–712. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, & Green S (Eds.). (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Vol. 4). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, & Altman DG (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 327(7414), 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Kurti AN, & Davis DR (2019). Voucher-based contingency management is efficacious but underutilized in treating addictions. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 42(3), 501–524. 10.1007/s40614-019-00216-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorthøj CR, Hjorthøj AR, & Nordentoft M (2012). Validity of timeline follow-back for self-reported use of cannabis and other illicit substances—Systematic review and meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 37(3), 225–233. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Iguchi MY, Belding MA, Morral AR, Lamb RJ, & Husband SD (1997). Reinforcing operants other than abstinence in drug abuse treatment: An effective alternative for reducing drug use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(3), 421–428. 10.1037/0022-006X.65.3.421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, & Wang MC (1999). Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 563–570. 10.1037/0022-006X.67.4.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, & McCance-Katz E (2015). National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. American Journal of Public Health, 105(8), e55–e63. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jones HE, Wong CJ, Tuten M, & Stitzer ML (2005). Reinforcement-based therapy: 12-month evaluation of an outpatient drug-free treatment for heroin abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 79(2), 119–128. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KC, Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, & Kerwin ME (2006). Substance abuse treatment providers’ beliefs and objections regarding contingency management: Implications for dissemination. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 85(1), 19–27. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte JE, Magruder KM, Chiuzan CC, Logan SL, Killeen T, Bandyopadhyay D, & Brady KT (2011). Assessing drug use during follow-up: Direct comparison of candidate outcome definitions in pooled analyses of addiction treatment studies. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(5), 358–366. 10.3109/00952990.2011.602997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EB, An W, Levin ME, & Twohig MP (2015). An initial meta-analysis of acceptance and commitment therapy for treating substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 155, 1–7. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, & Wilson DB (2001). Practical meta-analysis. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, & Burke BL (2010). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(2), 137–160. 10.1177/1049731509347850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, & Higgins ST (2006). A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction, 101(2), 192–203. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, & Ray LA (2009). Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(4), 516–527. 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Ray L, Kiluk B, Hoadley A, Bernstein M, Tonigan JS, & Carroll K (2019). A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol or other drug use disorders: Treatment efficacy by contrast condition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(12), 1093–1105. 10.1037/ccp0000447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, & Kang SY (1996). Validity of self-reported drug use in high-risk populations: A meta-analytical review. Substance Use & Misuse, 31(9), 1131–1153. 10.3109/10826089609063969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McDonell MG, Srebnik D, Angelo F, McPherson S, Lowe JM, Sugar A, Short RA, Roll JM, & Ries RK (2013). Randomized controlled trial of contingency management for stimulant use in community mental health patients with serious mental illness. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(1), 94–101. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11121831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern MP, Fox TS, Xie H, & Drake RE (2004). A survey of clinical practices and readiness to adopt evidence-based practices: Dissemination research in an addiction treatment system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26(4), 305–312. 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, & Kleber HD (2000). Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(13), 1689–1695. 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendeley Desktop. (2017). Getting started with Mendeley. Mendeley Ltd. http://www.mendeley.com [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyeloff JL, Fuchs SC, & Moreira LB (2012). Meta-analyses and Forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: Step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Research Notes, 5(1), 52. 10.1186/1756-0500-5-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notley C, Gentry S, Livingstone-Banks J, Bauld L, Perera R, & Hartmann-Boyce J (2019). Incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Advance online publication. 10.1002/14651858.CD004307.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peace MR, Tarnai LD, & Poklis A (2000). Performance evaluation of four on-site drug-testing devices for detection of drugs of abuse in urine. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 24(7), 589–594. 10.1093/jat/24.7.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Peirce JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Kellogg S, Satterfield F, Schwartz M, Krasnansky J, Pencer E, Silva-Vazquez L, Kirby KC, Royer-Malvestuto C, Roll JM, Cohen A, Copersino ML, Kolodner K, & Li R (2006). Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment: A National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(2), 201–208. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM (2012). Contingency management for substance abuse treatment: A guide to implementing this evidence-based practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- *Petry NM, Alessi SM, Barry D, & Carroll KM (2015). Standard magnitude prize reinforcers can be as efficacious as larger magnitude reinforcers in cocaine-dependent methadone patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 464–472. 10.1037/a0037888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Petry NM, Alessi SM, Carroll KM, Hanson T, MacKinnon S, Rounsaville B, & Sierra S (2006). Contingency management treatments: Reinforcing abstinence versus adherence with goal-related activities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 592–601. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Petry NM, Alessi SM, & Ledgerwood DM (2012). A randomized trial of contingency management delivered by community therapists. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(2), 286–298. 10.1037/a0026826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, & Tardif M (2005). Vouchers versus prizes: Contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1005–1014. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Olmstead TA, Rash CJ, & Zajac K (2017). Contingency management treatment for substance use disorders: How far has it come, and where does it need to go? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 897–906. 10.1037/adb0000287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Petry NM, Barry D, Alessi SM, Rounsaville BJ, & Carroll KM (2012). A randomized trial adapting contingency management targets based on initial abstinence status of cocaine-dependent patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(2), 276–285. 10.1037/a0026883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, DePhilippis D, Rash CJ, Drapkin M, & McKay JR (2014). Nationwide dissemination of contingency management: The Veterans Administration initiative. The American Journal on Addictions, 23(3), 205–210. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12092.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, & Rounsaville BJ (2004). Prize reinforcement contingency management for treating cocaine users: How low can we go, and with whom? Addiction, 99(3), 349–360. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00642.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Petry NM, Weinstock J, & Alessi SM (2011). A randomized trial of contingency management delivered in the context of group counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(5), 686–696. 10.1037/a0024813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Petry NM, Weinstock J, Alessi SM, Lewis MW, & Dieckhaus K (2010). Group-based randomized trial of contingencies for health and abstinence in HIV patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(1), 89–97. 10.1037/a0016778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, & Roll J (2006). Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 101(11), 1546–1560. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Silverman K, Higgens ST, Brooner RK, Montoya I, Schuster CR, & Cone EJ (1998). Cocaine use early in treatment predicts outcome in a behavioral treatment program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(4), 691–696. 10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Preston KL, Umbricht A, & Epstein DH (2002). Abstinence reinforcement maintenance contingency and one-year follow-up. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 67(2), 125–137. 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00023-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash CJ, Alessi SM, & Zajac K (2020). Examining implementation of contingency management in real-world settings. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 34(1), 89–98. 10.1037/adb0000496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash CJ, & DePhilippis D (2019). Considerations for implementing contingency management in substance abuse treatment clinics: The Veterans Affairs initiative as a model. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 42(3), 479–499. 10.1007/s40614-019-00204-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash CJ, DePhilippis D, McKay JR, Drapkin M, & Petry NM (2013). Training workshops positively impact beliefs about contingency management in a nationwide dissemination effort. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(3), 306–312. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash CJ, Petry NM, Kirby KC, Martino S, Roll J, & Stitzer ML (2012). Identifying provider beliefs related to contingency management adoption using the Contingency Management Beliefs Questionnaire. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 121(3), 205–212. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash CJ, Stitzer M, & Weinstock J (2017). Contingency management: New directions and remaining challenges for an evidence-based intervention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 72, 10–18. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rawson RA, Huber A, McCann M, Shoptaw S, Farabee D, Reiber C, & Ling W (2002). A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches during methadone maintenance treatment for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(9), 817–824. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rawson RA, McCann MJ, Flammino F, Shoptaw S, Miotto K, Reiber C, & Ling W (2006). A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches for stimulant-dependent individuals. Addiction, 101(2), 267–274. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Meredith LR, Kiluk BD, Walthers J, Carroll KM, & Magill M (2020). Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with alcohol or substance use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open, 3(6), e208279. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Roll JM, Chudzynski J, Cameron JM, Howell DN, & McPherson S (2013). Duration effects in contingency management treatment of methamphetamine disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 38(9), 2455–2462. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, & Badger GJ (1996). An experimental comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29(4), 495–505. 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Madden GJ, Rawson R, & Petry NM (2009). Facilitating the adoption of contingency management for the treatment of substance use disorders. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 2(1), 4–13. 10.1007/BF03391732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Roll JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Brecht ML, Peirce JM, McCann MJ, Blaine J, MacDonald M, DiMaria J, & Kellogg S (2006). Contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine use disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(11), 1993–1999. 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozen HG, Boulogne JJ, van Tulder MW, van den Brink W, De Jong CA, & Kerkhof AJ (2004). A systematic review of the effectiveness of the community reinforcement approach in alcohol, cocaine and opioid addiction. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 74(1), 1–13. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R (1979). The ‘file drawer problem’ and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh CS, Huey SJ Jr., Zara EJ, & Jhaveri K (2017). Follow-up treatment effects of contingency management and motivational interviewing on substance use: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(4), 403–414. 10.1037/adb0000277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Lechner WV, Carter RE, & Malcolm R (2009). Temporal and gender trends in concordance of urine drug screens and self-reported use in cocaine treatment studies. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 3(4), 211–217. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181a0f5dc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Shoptaw S, Reback CJ, Peck JA, Yang X, Rotheram-Fuller E, Larkins S, Veniegas RC, Freese TE, & Hucks-Ortiz C (2005). Behavioral treatment approaches for methamphetamine dependence and HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among urban gay and bisexual men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 78(2), 125–134. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Silverman K, Robles E, Mudric T, Bigelow GE, & Stitzer ML (2004). A randomized trial of long-term reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in methadone-maintained patients who inject drugs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 839–854. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Peirce J, Petry NM, Kirby K, Roll J, Krasnansky J, Cohen A, Blaine J, Vandrey R, Kolodner K, & Li R (2009). Abstinence-based incentives in methadone maintenance: Interaction with intake stimulant test results. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 15(4), 344–350. 10.1037/1064-1297.15.4.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Friedman L, Greenfield SF, Hasin DS, & Jackson R (2012). Beyond drug use: A systematic consideration of other outcomes in evaluations of treatments for substance use disorders. Addiction, 107(4), 709–718. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03581.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE (2015). How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 270–277. 10.1002/wps.20238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbring ML, Kivlahan D, Kenny M, Grillo M, Hagedorn H, & Postier A (2004). Beliefs about evidence-based practices in addiction treatment: A survey of Veterans Administration program leaders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26(2), 79–85. 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00161-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.